Transformative Change in Peri-Urban SEPLS and Green Infrastructure Strategies: An Analysis from the Local to the Regional Scales in Galicia (NW Spain) (SITR6-8)

23.04.2021

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

University of Santiago de Compostela

DATE OF SUBMISSION

23/04/2021

REGION

Europe

COUNTRY

Spain

KEYWORDS

Green infrastructure · Strategic planning · Ecosystem services · Common land · Ecosystem management · Transformative change

AUTHOR(S)

Emilio Díaz-Varela, Guillermina Fernández-Villar, and Alvaro Diego-Fuentes

E. Díaz-Varela· G. Fernández-Villar

Higher Polytechnic School of Engineering, University of Santiago de Compostela, Lugo, Spain

A. Diego-Fuentes

Community Facilitation & Environmental Education – Neighbourhood Association of Chapela, Pontevedra, Spain

LINK

Abstract

Transformative change involves the integration of different social dimensions and the involvement of a multiplicity of actors resulting in high levels of complexity. Considering all this, our work addresses the development of green infrastructure (GI) to improve the conservation of biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services from two different approaches and scales: regional and local.

From the regional level, a GI strategy was promoted by the regional government of Galicia (NW Spain) through institutional efforts following a multidisciplinary approach including public participation processes. On the other hand, a local, participative perspective is exemplified in the Neighbourhood Association of the Parish of Chapela (Redondela, Galicia), a peri-urban, coastal area where intensive forestry and urban expansion threatens the availability of accessible multifunctional ecosystems for the local communities.

Both approaches are indicative of seeds for a transformative change yet to happen. Nevertheless, they differ in their visions, values and goals: the regional level is statutory-oriented and focused on the accomplishment of administrative objectives; the local level is based on the communities’ wellbeing aims and calls- for-action. Differences are also detected in the risks and barriers to transformative processes, from the inertia of administrative procedures to the limitations of local action to face environmental and developmental problems. Exploration of these contrasting perspectives leads to the identification of needs for institutional change, the emergence of new governance systems, and the development of new perspectives for strategic planning and management.

1. Introduction

1.1 The Different Levels of Transformative Change

The increasing impact of human activities on ecosystems and the general decline of life on Earth, well documented in the recent Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) Global Assessment (IPBES 2019a, b), call for transformative change to halt the future trajectories of the continuous decline of living systems and their related contributions to people (McAlpine et al. 2015; Díaz et al. 2019). Such transformative change depends on the application of governance mechanisms (‘levers’) on the priority intervention ‘lever- age’ points described in Chap. 1 of this SITR volume. Specifically, in the nexus approach to achieve the SDGs described in the aforementioned IPBES report, the aim of “sustaining cities while maintaining the underpinning ecosystems (both local and regional) and their biodiversity” is included (Chan et al. 2019, p. 8), addressing specifically goals 11 (Sustainable cities and communities) and 15 (Life on land) of the SDGs. City-specific targets, including retention of species and ecosystems and limits on urban transformation, are to be achieved by strengthening local- and landscape-level governance and enabling transdisciplinary planning to bridge sec- tors and departments, and to engage businesses and other organisations in protecting public goods. This focus integrates the achievement of biodiversity conservation objectives with those geared to improvement of local quality of life. In this sense, the integration of ecological (‘green’) and built (‘grey’) infrastructure are considered as increasingly important (Chan et al. 2019, p. 8), being the design and maintenance of ecological connectivity across the territory, and specifically in the interfaces between urban and rural areas, critical for both people and nature.

In alignment with these objectives, the European Union in its Biodiversity Strategy to 2020 states its Target 2 as follows: “By 2020, ecosystems and their services are maintained and enhanced by establishing green infrastructure and restoring at least 15% of degraded ecosystems” (European Commission 2011,

- 12). To this end, a strategy for green infrastructure was developed (European Commission 2013a). In it, green infrastructure (GI) is defined as

.. .a strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services. It incorporates green spaces (or blue if aquatic ecosystems are concerned) and other physical features in terrestrial (including coastal) and marine areas. On land, GI is present in rural and urban settings (European Commission 2013a, p. 3).

The vision is essentially multifunctional (DG Environment 2012), and is considered as a successfully tested tool for providing ecological, economic and social benefits through natural solutions, contributing to comprehension of the value of nature benefits to society and to mobilising investments to sustain and reinforce them (European Commission 2013a). The strategy should be implemented at the national level by the EU state members, which in turn would coordinate the implementation at the regional level. Thus, in Spain, the development of a “State-level Strategy for Green Infrastructure and Ecological Connectivity and Restoration” was approved (eds. Valladares et al. 2017), being the framework to carry out regional-level strategies by the different autonomous communities. One of the autonomous com- munities pioneering the development of a GI strategy was Galicia.

In Galicia, despite deep structural and functional changes suffered by rural areas, cultural landscapes still persist as socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS) in many rural areas (Calvo-Iglesias et al. 2006, 2009; Morán- Ordóñez et al. 2011). Nevertheless, there are still examples of SEPLS in peri-urban areas continuously evolving due to the influence of diverse and complex driving forces and interrelationships: urban development, urban-rural interaction, peri-urban communal land dynamics, etc. (Souto-González 1993; Swagemakers and Dominguez-García 2015; Dominguez-Garcia et al. 2015). The local communities living in these geographical areas participate in their management espousing different visions, values and perspectives, from productive activities to environmental conservation. How may these activities lead to transformative change at the local level? And how does this relate to the top-down implementation of green infrastructure strategies at the regional level?

1.2 Objectives

We aim to compare two different approaches at the regional and local level under the same research question: How is the development of green infrastructure elements achieved in order to improve the conservation of biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services? The first, developed by the regional administration, provides a statutory framework for action. The second, developed by a local “Neighbourhood Association” in Chapela (Redondela, Spain), exemplifies the emergence of new values in local communities and institutions leading to the demand for a better environment. The analysis of both perspectives allows for a systemic approach to the governance system, its elements and interactions, leading to the acknowledgement of not only how transformative processes may emerge, but also of the limitations, risks and barriers involved in changes yet to happen in peri-urban SEPLS.

2 Material and Methods

2.1 Study Area

The approach taken in this work addresses two geographical levels: regional and local (Figs. 8.1 and 8.2 and Table 8.1). The regional level (Fig. 8.1) is represented by the Autonomous Community of Galicia, NW Spain (Framed between latitudes 43 480 N and 41 490 N and longitudes 6 440 W and 9 180 W). It spans 29,577 km2 and has 2,698,764 inhabitants (INE 2019). The region is located in the Atlantic biogeographical region and is characterised by an oceanic temperate climate, with zones of Mediterranean climate influences. Land uses are occupied by artificial surfaces (6.52%), surface waters (0.79%), crops (24.56%), forestry areas (17.12%), native forests (14.98%), shrubland and pastures (31.21%) and other ecosystems (4.81%) (SIOSE 2011). The region is to a large extent rural, with some concentration of industrial activity in the metropolitan areas of A Coruña, Ferrol and Vigo.

The local level (Fig. 8.2) is represented by a peri-urban coastal area near the aforementioned city of Vigo. The area was defined by the basins of four small streams (Cabras, Fondón, Maceiras and Pugariño) flowing E-W through the rural- urban gradient. The main settlements are Cidadelle, Angorén, Laredo, A Igrexa and Parada, in the parish of St. Fausto of Chapela; Trasmañó, Igrexa and Cabanas in St. Vicente of Trasmañó; and O Pugariño, in St. Salvador of Teis. Parishes are historical, non-statutory territorial units still in use for local organisational purposes. The former two are in the municipality of Redondela, and the latter, in the municipality of Vigo. The total population is 8,567 inhabitants (INE 2019). The area shows a close interface between urban (residential and industrial) uses and forestry areas (mainly comprised of Eucalyptus globulus plantations and shrubland). Both intensive land uses put pressure on riparian and forest ecosystems (which include the Prunus lusitanica species of tree, classified by IUCN as “vulnerable”) that local communities wish to preserve. Forest areas still involve ownership regimes known as “Communal Forest Land” (“Montes Veciñais en Man Común” (MVMC) in Galician language). The MVMC are community managed, and all decisions are made democratically through the assembly of the Community of MVMC (CMVMC), with a board acting as representative body. Generally, each MVMC corresponds to a parish or settlement, and the main ones in the area are those of Chapela, Teis, Candeán, Cabeiro, Trasmañó and Cedeira (Fig. 8.2).

2.2 Methodological Approach

2.2.1 Document Analysis

Documents relevant to the study case were reviewed in order to identify keywords and specific contents related to the views, values and perspectives needed for transformative change. Such documents included the current regulations at the European level regarding biodiversity conservation and green infrastructure (European Commission 2011, 2013a). Also, at the national level, the documents regarding the next Green Infrastructure Strategy (eds. Valladares et al. 2017) were reviewed. At the regional level, the Galician GI Strategy website (Infraestructura Verde de Galicia 2019), as well as the unpublished documents from the team commissioned for the development of the Strategy (see next section), were included. Finally, some of the documents prepared by the Neighbor Association of Chapela were reviewed, including their transversal programme for environmental education and heritage (Diego Fuentes 2019), and their proposal for the improvement of the municipal Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (PMUS) (Neighbourhood Association of Chapela 2019).

2.2.2 Spatial Analysis

Spatial data, including vectorial and raster GIS and remote sensing data from the National Geographic Institute of Spain (Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica 2019), as well as the Spatial Data Infrastructure from Galicia (Xunta de Galicia 2019) was used to analyse the temporal evolution of the SEPLS, alongside the proposals made by the Neighbourhood Association of Chapela.

2.2.3 Direct Observation

The direct participation of all the authors in the different levels addressed in this work allowed for direct observation of developments and outcomes. One of the co-authors, Alvaro Diego Fuentes, is the environment delegate of the Neighbourhood Association of Chapela. The lead-author, Emilio Díaz-Varela, participated in the development of the Galician GI Strategy as one of the interdisciplinary team members. Finally, the other co-author, Guillermina Fernandez-Villar, developed an academic work (Fernandez-Villar 2019), analysing the proposals of the Neighbourhood Association of Chapela from the point of view of green infra- structure implementation. The information retrieved as a result of direct observation was the source used to develop the indicators (see Sect. 8.2.2.4).

2.2.4 Indicators

In order to characterise the differences between the two analysed approaches, we developed a set of indicators specific for this work. These indicators allow for summarising and conclusions on both perspectives. Due to the character of the information to be retrieved and to the methodological approach, all the indicators used are of qualitative and descriptive character. They are described as follows:

- Vision: The general purpose envisaged for the GI

- Triggers: The enabling factors for GI development

- Approach: The general view for implementation of the GI

- Coordination: How the institutional and other actors involved or interested in the GI would be coordinated for implementation

- Aims: Specific objectives and implementation levels of the GI

- Means: How the aims would be put into practice

- Identified barriers: How the current configuration of the governance system could hinder implementation of GI supportive of transformative change

- Identified needs: Elements to overcome the identified barriers

3 Results: Two-Level Approach Towards Green Infrastructure

3.1 The Regional Level: Statutory Approach

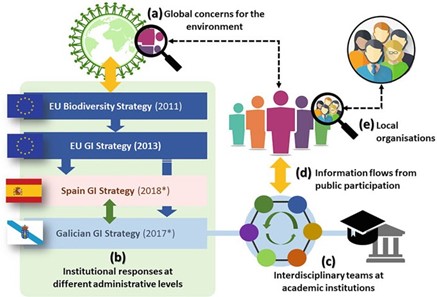

The Galician GI Strategy responds to the application of European-level directives related to biodiversity and green infrastructure (European Commission 2011, 2013a), and is coordinated with the state-level GI Strategy (See Fig. 8.3b). In this sense, it responds to the global demands of society for environmental conservation (See Fig. 8.3a), being coherent with the city-specific targets described in the IPBES Global Report for transformative change (Chan et al. 2019, p. 8). For the development of the Galician GI Strategy, the (then) Regional Ministry for Environment and Land Use Planning (CMAOT) commissioned a multidisciplinary team coordinated by the Institute of Territory Studies (IET) and composed of three research groups of the University of Santiago de Compostela (USC) and two from the University of A Coruña (UDC). Later, a private company specialising in sociological studies (DELOGA) joined the team for the development and organisation of the public participation (sub-) strategy. The approach was then statutory, combining a top-down design with the integration of bottom-up suggestions and information coming from the public participation sub-strategy. The agreement for the multidisciplinary team was signed in August 2017, and the project was planned to be developed in 16 months.

Fig. 8.3 Governance chart for the development of Green Infrastructure at different scales. Note: (a) Global concern in societies and institutions demands action for conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem services. (b) Organisations at different levels respond with regulations focused in GI Strategies (among others). (c) At the regional level, interdisciplinary groups assume the collaboration between regional government and academia to develop GI strategies. (d) Public participation processes are developed to integrate the needs and visions of the population. (e) Local organisations at local levels contribute their visions and needs

The methodological approach was structured in seven working packages (WPs): WP0, to be developed by IET, was project management and coordination. WP1 (Biodiversity Mapping), WP2 (Ecosystem Service Mapping), WP3 (Delineation of Green Infrastructure Elements), WP4 (Socio-economic Implementation), and WP5 (Formalisation of Directives and Specific Strategies) were developed in a coordinated effort by the USC and UDC teams, with the support of IET. Finally, WP6 (Public Participation) was developed by DELOGA, but USC, UDC and IET collab- orated on the participative events.

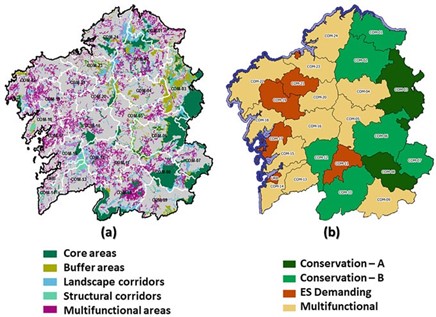

Figure 8.4 summarises the Galician GI Strategy in two graphic examples. The first (Fig. 8.4a) shows the network of green infrastructure elements, including core and buffer areas, landscape and structural corridors, and multifunctional zones. The second (Fig. 8.4b) classifies Galicia in sub-regional areas, where three different sub-strategies for socioeconomic improvement related to GI and ecosystem services were developed. These were adapted to the social-ecological demands of each area, and integrated the results of the public participation: conservation (addressed to sub-regional areas with more (A) or less (B) core areas), multifunctional (sub-regional areas with a combination of different GI elements), and ecosystem service demanding (sub-regional areas with scarce GI elements).

Fig. 8.4 Results at the regional level: (a) GI elements and their typologies; (b) sub-regional social- ecological units. See text for details. (Source: Modified from Díaz-Varela et al. 2018)

3.2 The Local Level: Community Approach

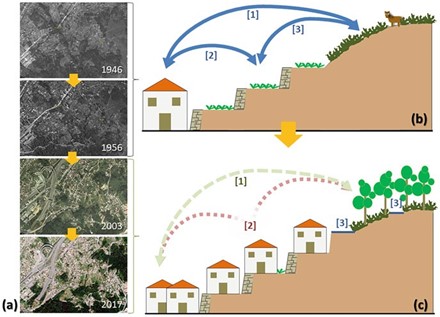

The evolution of the SEPLS in the area of Chapela (see Sect. 8.2.1) is important for the comprehension of current dynamics. The analysis of aerial photographs from 1946 to 2017 (Fig. 8.5a) shows a rapid decline in the social-ecological system due to the expansion of urban fabric and linear infrastructure. Such changes degraded the system and the strong relationships between settlements, ‘infield’ terraced structures, and ‘outfield’ productive shrubland (Bouhier 2001; see Fig. 8.5b, 1-2-3). Progressive non-planned, spontaneous urbanisation used former structures to build houses and roads (Fig. 8.5c, 2-3), and the breakage of the relationship between ‘infield’ and ‘outfield’ induced afforestation in the former (Fig. 8.5c, 1). Newcomers with little relationship with the former social-ecological system also altered the composition and function of the social fabric: a new SEPLS was formed, with novel needs and expectations regarding green infrastructure, derived from specific perspectives and values. Thus, instrumental values centred in the productivity of the territory have lost relevance (even while basic forestry activities remain), while new relational values have been revealed through new needs for the community’s environmental quality, which in turn underpin management perspectives and sustainability visions for the SEPLS.

Fig. 8.5 Evolution of the social-ecological system: (a) Aerial photographs of part of the study area taken in 1946, 1956, 2003 and 2017 show the changes that have taken place in the system. (b) Schematic interpretation of the social-ecological system towards the 1950s; and (c) towards the 2020s. See text for details

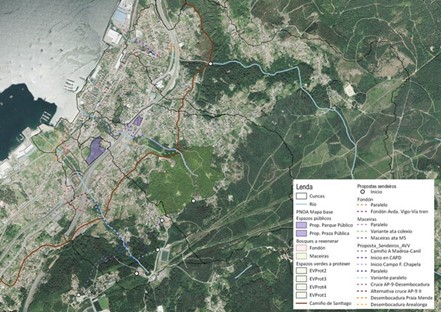

It is in this context that the Neighbourhood Association of Chapela was developed. This is a non-governmental, non-profit association founded to defend the interests and needs related to the wellbeing of the community, including the improvement of its environment. To this end, the association makes requests to local and regional administrations for interventions in the environmental improvement of the neighbourhood. These are normally accompanied by well-developed reports and recommendations of a strategic character. Examples range from contributions to the Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (PMUS) and the General Municipality Urban Plan (PXOM) at the local level (Fig. 8.6), to the Galician Strategy of Circular Economy, and also the Galician Green Infrastructure Strategy discussed herein (Fig. 8.4). The proposals are also oriented to generation of environment- related employment, a social component that may be crucial for attitude changes.

Fig. 8.6 Example of the spatial planning proposals made by the Neighbourhood Association of Chapela. The map reflects the community’s vision to overcome the environmental restrictions of the area through development of site-level greenways, corridors and open spaces, establishing the desired green infrastructure (Source: Neighbourhood Association of Chapela 2019; Fernandez- Villar 2019)

On the other hand, the association also is highly involved in educational projects, oriented toward transformation and the encouragement of participatory citizenship. These include talks and workshops in schools to disseminate information on waste management, programmed obsolescence and the encouragement of circular economy with a holistic approach. Students are taught that the right to a good environment and to sustainable development are a part of human rights. Also, participatory activities, such as excursions to clean up waste in local riverbeds, are conceived as educational events where students are stimulated to reflect on the consequences of social and environmental activities in production and consumption processes (Fig. 8.7). The design of this educational approach is strongly based on social psychology and social change theories, and aims to be of a transformative character.

Fig. 8.7 Participatory excursion to clean up waste in riverbeds and associated heritage elements. The activities are designed to create an affective link with the environment

4 Implications for Transformative Change: Visions, Values... and Barriers

4.1 The Regional Level

The initial agreement for the development of the Galician GI Strategy (Xunta de Galicia 2017, p. 5) is oriented towards an institutional instrument integrative for land planning, green infrastructure development, and functional connections between landscapes and territories. These aims show an alignment with the visions behind EU and state directives, specifically with the integrative orientation of the EU GI Strategy, which aims to make a significant contribution to regional development, climate change, disaster risk management, agriculture/forestry and the environment (European Commission 2013a).

The vision is, thus, a “smart solution for today’s needs” (European Commission 2013b) integrating conservation of natural capital and biodiversity, enhancement of ecosystem services provision, and economic development, trying to respond to the concerns in societies and institutions regarding such, as well as the basic components of wellbeing (see Fig. 8.3a, b). Nevertheless, a strategic spatial planning component to the GI was included at the regional level. While this is a desirable aspect in the implementation of green infrastructures (Lennon and Scott 2014; Grădinaru and Hersperger 2019), current approaches to such integration are considered insufficient (Ronchi et al. 2020), and the need for new integrative, adaptive and participative approaches is indicated, implying complete institutional change at multiple levels of governance, including administrative bodies, competence of practitioners and capacity building for public participation (Botequilha-Leitão and Díaz-Varela 2020). For instance, in Galicia, the spatial planning system presents coordination problems between different levels and sectoral approaches (Lois-González and Aldrey- Vázquez 2010; Tubío-Sánchez and Crecente-Maseda 2016). Also, institutional barriers and short-term vision have affected the regional GI Strategy. Namely, changes in governance (Decree 42/2019) during the final stages of its development modified the institutional staff in charge of the strategy, resulting in changes in priorities and visions, and a delay in the stages crucial for implementation of the strategy. Consequently, transformative change must involve not only planning and institutional systems, but also innovative governance approaches that need to be integrative, inclusive, informed and adaptive (Díaz et al. 2019). These approaches should catalyse change through multilevel/multiscale learning, connecting through the diverse boundaries of knowledge, values, levels and organisations (Granberg et al. 2019).

4.2 The Local Level

At the local level, visions are largely developed based on immediate perception of the environment by local inhabitants. In fact, one important trigger in Chapela was the restricted mobility sensed by the community: non-planned urban structures constrained pedestrian movement, as current streets and roads were built by paving pre-existent pathways more suitable for vehicular traffic, neglecting walkways. Paradoxically, this progressively hindered both access to public transportation and pedestrian mobility. The development of a complex network of highways and railways in the last decades (Fig. 8.5a) aggravated the problem. In a search for solutions, the Neighbourhood Association of Chapela made proposals for reactivating pedestrian communications throughout the peri-urban fabric, and also access to the common forests up in the hills (Fig. 8.6). Interestingly, as some of the old paths follow streams and brooks, efforts made for their reclamation led to an increased awareness of the associated natural and cultural heritage. The involvement of the association in the clean-up of riverbeds, where waste had accumulated over decades of dumping—another consequence of the lack of urban planning (Fig. 8.7)—contributed to a reappropriation of the environment by the community, including the discovery of traditional watermills in the area as important cultural heritage elements, leading to serious efforts for their recovery. The activities of the association are thus intended to provide an educational experience, designed with a strong basis in social psychology. Specifically, collective events for clean-up of riverbeds are aimed at effecting changes in attitudes and behaviour through participation. The resulting emotional involvement has proved to be in this sense more effective than analytical thinking (Small et al. 2007). The consequent participation involves the valuation and appropriation of the environment by the participants (Cooney 2010), and an increasing understanding of the former social-ecological system. In this sense, these activities promote elements of transformational change (McAlpine et al. 2015), involving ethical responsibility in dealing with people and environment, community integration, and reconnecting with and valuing nature.

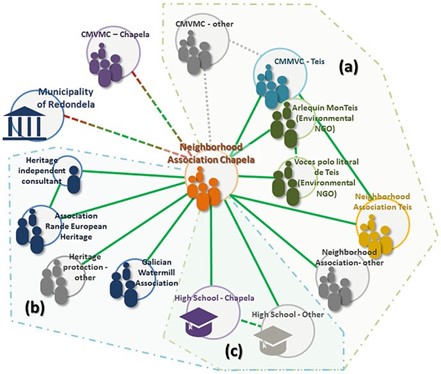

Fig. 8.8 Stakeholder map of Chapela showing the different ‘cliques’ or sub-networks defined by stronger thematic ties: (a) environmental cooperation clique; (b) cultural heritage cooperation clique; (c) educational clique. Green connections: active; red-green: to be improved; grey discontinuous: to be consolidated. Degree of discontinuity in lines is proportional to the strength of the ties

The strong relationships held by the association with other local organisations (Fig. 8.8) are also an important element for transformative change, and necessary for effective adaptation when transformative change goes beyond administrative and territorial boundaries (Granberg et al. 2019). Thus, environment-related activities are carried out with other neighbour associations and environmental NGOs (Fig. 8.8a), as well as with adjacent communal forests (CMVMCs; see Sect. 8.2.1). Collaborative educational activities are also carried out with the high school of Chapela (and others). Still, the association holds divergent views from those of the CMVMC of Chapela concerning the management of the communal forest. Currently, this CMVMC has delegated management duties to a private company (a possible symptom of institutional apathy), putting focus on the production of fast-growing species for timber. The vision represented by the association, though, is more related to the multifunctional use of the forest and the generation of employment via projects, including edible forests or permaculture. Nevertheless, new negotiations are planned in search of common ground. Finally, the association also interacts with different levels or government, mainly at the local level, but also at the regional level. Nevertheless, some of the association’s suggestions for environmental initiatives have come up against barriers. As local administration, the municipality has been reactive to initiatives that are unusual in their strategic, collaborative implementation. Yet, when the association invited municipality representatives to the area to see in situ the current state and motivations for the actions, some changes in the municipality’s visions and attitudes took place. The association also took part in public participation sessions for the development of the Galicia GI Strategy, with their initiatives included as examples of potential local-based actions by NGOs.

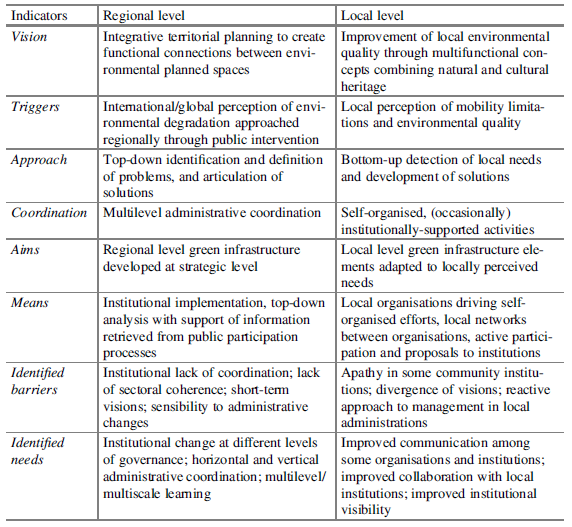

4.3 Local vs. Regional Approaches: Indicators and Lessons Learned

Table 8.2 shows a comparison between the two analysed levels, based on the set of indicators described in Sect. 8.2.2.4. The descriptions associated with each indicator are related to the respective contributions of the actions for implementation of GI at each level to transformational change.

It is possible to identify a convergence in both approaches towards the improvement of environmental conditions in the territory, via the implementation of actions through GI. Nevertheless, clear differences can also be detected, associated with their top-down and bottom-up characteristics. Thus, for instance, the regional level pursues integrative territorial planning triggered by the society’s perception of environmental degradation, while at the local level the focus is on the improvement of the neighbouring environment based on local perception of mobility limitations and environmental quality. In a similar way, GI-based solutions are adopted through institutional actions at the regional level, whereas at the local level community initiatives and network coordination are much more relevant. Consequently, the identified needs and barriers are consistent with these differences in the scale-based approaches.

Table 8.2 Detailed comparison between regional and local levels defined for the set of indicators

As discussed in Chap. 1 of this volume, enabling transformative change implies implementation of priority interventions, or “levers”, targeting key points of intervention, or “leverage points”. Effective use of levers and leverage points requires innovative governance approaches and organising the process around nexuses (Díaz et al. 2019). Thus, on the one hand, new models of governance should target the integration of multidirectional information (including iterative learning loops) and connections at different levels. On the other hand, nexuses represent closely interdependent and complementary goals, and reflect interactions between multiple sectors and objectives. In this sense, implementation of GI strategies, a basic element in the nexus approach for “sustaining cities while maintaining the underpinning ecosystems and their biodiversity”, becomes a tool for achieving interlinked goals. In this work, the lessons learned for transformative change are related to both requirements. Different potentials and constraints can be interpreted through the levers as governance mechanisms applied at regional and local scales through their related leverage points; for instance:

- Incentives and capacity building for environmental responsibility are already a central element in the educational and other initiatives analysed at the local Focusing on improvement of quality of life in the neighbourhood and the removal of waste serve as ways to comprehend the consequences of consumption dynamics. This allows for the potential to use GI to aim directly towards envisioning a good quality of life while lowering total consumption and waste.

- Cross-sectoral cooperation, avoiding segmented decision-making and promoting integration across jurisdictions, is one of the main needs identified in the process, and would include institutional change at the regional level, collaboration among local-level institutions, and improved communication, coordination and integration between Current deficiencies in this lever are translated into ill-implemented regional strategies and local initiatives that lack reach, thus hindering the transformative potential at all scales.

- Pre-emptive action to avoid, mitigate and remedy the deterioration of nature can be seen as one of the motivations of GI implementation, motivating the development of strategies at different Activation by unleashing values and action, reducing inequalities and practicing justice and inclusion in conservation as key points may boost the capacity of GI to achieve the interlinked goals of the nexus.

- Decision-making in the context of resilience and uncertainty is nowadays a big challenge at any of the studied levels. The identified barriers, related to the approach, coordination and means of strategic planning, reveal deficiencies in its adaptive character, thus being hardly capable to cope with uncertainty and Inclusion of new perspectives for strategic planning in innovative governance schemes could provide adaptive decision-making articulated through social innovation, adaptive management and similar points of action.

- Environmental law and implementation will be one of the bases for the application of GI at the regional level. At the local level, it is perceived that the enforcement of existing environmental law would overcome many of the current barriers and constraints for the improvement of environment through community- designed GI elements. Well-planned implementation of environmental law would help to unleash the latent values of responsibility and social norms for sustain- ability leading to action.

5 Conclusions

Transformations taking place at the local level are guiding a transition in the studied SEPLS from the traditional agricultural system to the current one, where the local inhabitants are developing a new relationship with their environment based on the continuous development of new visions. In this sense, bottom-up implementation of green infrastructure elements emerges from needs identified by the community regarding their wellbeing and conducted through a Neighbourhood Association. Specific actions are centred in the reclamation of riparian and forest ecosystems as multifunctional greenways. Clean-up of dumped trash, recovery of heritage sites and educational activities are developed to encourage holistic views for the transformation towards a circular economy at the local level, including employment opportunities. Key components are the involvement of the community, the development of a network of organisations, and collective leadership. Institutional support by the local and regional government is perceived, though, as essential, and its absence may cause limitations to the transformation potential of the association.

The efforts developed at the regional level addressing transformative change are mainly statutory, top-down in character, with the transposition of directives coming from upper levels being an important motivation for green infrastructure implementation. This view is complemented by public participation to integrate bottom-up perspectives and visions. As such, it could be a reference point for identifying and developing learning loops. As implementation at the regional level is associated to spatial planning, there is a strong dependence on institutional and governance structures. In this sense, barriers imposed by the lack of communication between administrations, deficits in sectorial coherence, short-term views and sensibility to changes in administration schemes evidence the need for institutional change. Such barriers may also affect initiatives developed at the local level, depriving them of institutional support. Also, they may preclude essential tasks such as assessment of the strategic interest of bottom-up initiatives, sectoral coordination, regulation enforcement, or valuation of financial opportunities. Additionally, to face the challenges involved in the transformative change, an essential role of the new governance schemes would be the identification of the priority, public and general interest of bottom-up initiatives aligned with sustainability goals to warrant their effective implementation.

As a concluding remark, the differences identified between the analysed levels (local and regional) and perspectives (community and statutory) highlight the need for deliberative, conversational approaches integrated in innovative governance schemes as a prerequisite for transformative change. Comprehension and activation of multi-actor governance ‘levers’ and ‘leverage points’ will be essential in this process.

References

Botequilha-Leitão, A., & Díaz-Varela, E. R. (2020). Performance based planning of complex urban social-ecological systems: the quest for sustainability through the promotion of resilience. Sustainable Cities and Society, 56, 102089.

Bouhier, A. (2001). Galicia. Ensaio xeográfico de análise e interpretación dun vello complexo agrario. Santiago de Compostela: Consellería de Agricultura, Gandería e Política Agroalimentaria (Xunta de Galicia).

Calvo-Iglesias, M. S., Crecente-Maseda, R., & Fra-Paleo, U. (2006). Exploring farmer’s knowledge as a source of information on past and present cultural landscapes: A case study from NW Spain. Landscape and Urban Planning, 78, 334–343.

Calvo-Iglesias, M. S., Fra-Paleo, U., & Diaz-Varela, R. A. (2009). Changes in farming system and population as drivers of land cover and landscape dynamics: The case of enclosed and semi- openfield systems in Northern Galicia (Spain). Landscape and Urban Planning, 90, 168–177. Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica. (2019). Centro de Descargas, Madrid, viewed 22 July 2020, http://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/index.jsp

Chan, K. M. A., Agard, J., & Liu, J. (2019). Chapter 5. Pathways towards a sustainable future. In E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, & H. T. Ngo (Eds.), Global assessment report of the Inter- governmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn: IPBES secretariat.

Cooney, N. (2010). Change of heart: What psychology can teach us about spreading social change. New York: Lantern Books.

Xunta de Galicia (2019). Información Xeográfica de Galicia, Santiago de Compostela, viewed 22 July 2019, http://mapas.xunta.gal/portada

Xunta de Galicia (2017). Convenio de colaboración entre a Consellería de Medio Ambiente e Ordenación do Territorio a través da Dirección Xeral de Patrimonio Natural e do Instituto de Estudos do Territorio, a Universidade de Santiago de Compostela (USC) e a Universidade da Coruña (UDC) para o deseño da estratexia de infraestrutura verde de Galicia cofinanciado nun 80% polo Fondo Europeo de Desenvolvemento Rexional no marco do Programa Operativo FEDER Galicia 2014–2020. Galicia: Galician Regional Government (Xunta de Galicia)

Decree 42/2019 – Decreto 42/2019 de 28 de marzo, por el que se establece la estructura orgánica de la Consellería de Medio Ambiente, Territorio y Vivienda (Galicia, Spain).

DG Environment. (2012). The multifunctionality of green infrastructure, Science for Environment Policy, DG Environment News Alert Service, In-Depth Report, March 2012. Brussels: European Commission.

Díaz, S., Settele, J., Brondízio, E. S., Ngo, H. T., Agard, J., Arneth, A., et al. (2019). Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science, 366 (6471), eaax3100.

Díaz-Varela, E., Ferreira-Golpe, M. A., García-Arias, A. I., Pérez-Fra, M., López-Iglesias, E., & Rodriguez-Morales, B. (2018). Capítulo 10: Estratexias para o aproveitamento das potencialidades da infraestrutura verde para o desenvolvemento socioeconómico. In Estratexia de Infraestrutura Verde de Galicia (Unpublished Draft). Xunta de Galicia: Instituto de Estudos e Desenvolvemento de Galicia (IDEGA) – Universidade de Santiago de Compostela (USC) – Instituto de Estudos do Territorio (IET) – Consellería de Medio Ambiente Territorio e Vivenda (CMATV).

Diego Fuentes, A. (2019). Programa transversal sobre educación ambiental, patrimonio e participación cidadá “Regatos e muiños.: paraísos baixo o lixo”. Kitchener: Neighbourhood Association of Chapela.

Dominguez-Garcia, D., Swagemakers, P., & Simon, X. (2015). Sustainable management of green space in the city-region of Vigo, Galicia (Spain). In Second international conference on agriculture in an urbanizing society reconnecting agriculture and food chains to societal needs, 14–17 September, Rome.

European Commission. (2011). Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions.

Our life insurance, our natural capital: an EU biodiversity strategy to 2020, COM (2011) 244 Final. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2013a). Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Green Infrastructure (GI) – Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital, COM (2013) 249 Final. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2013b). Building a green infrastructure for Europe. Brussels: European Commission.

European Environment Agency. (2017). Biogeographical regions in Europe, Copenhagen, viewed 2 November 2020, https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/biogeographical-regions- in-europe-2

Fernandez-Villar, G. (2019). Estudo das infraestruturas verdes da parroquia de chapela e colindantes e proposta alternativa ao modelo de aproveitamento agro-forestal actual, Final Degree Project, Agricultural and Agri-Food Engineering. Santiago de Compostela: University of Santiago de Compostela.

Grădinaru, S. R., & Hersperger, A. M. (2019). Green infrastructure in strategic spatial plans: Evidence from European urban regions. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 40, 17–28.

Granberg, M., Bosomworth, K., Moloney, S., Kristianssen, A.-C., & Fünfgeld, H. (2019). Can regional-scale governance and planning support transformative adaptation? A study of two places. Sustainability, 11(24), 6978.

INE. (2019). Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spanish Statistical Office) – Nomenclátor, Nomen- clátor: Población del Padrón Continuo por unidad poblacional, viewed 11 March 2020, http:// bit.ly/2WToH7L

Infraestructura Verde de Galicia. (2019). Infraestructura Verde de Galicia, Santiago de Compostela, viewed 9 March 2020, http://infraestruturaverdegalicia.gal/

IPBES. (2019a). IPBES rolling work programme up to 2030, IPBES, viewed 11 March 2020, https://ipbes.net/work-programme

IPBES. (2019b). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. In S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio, H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. R. Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, & C. N. Zayas (Eds.), IPBES Secretariat. Bonn: IPBES.

Lennon, M., & Scott, M. (2014). Delivering ecosystems services via spatial planning: reviewing the possibilities and implications of a green infrastructure approach. Town Planning Review, 85(5), 563–587.

Lois-González, R. C., & Aldrey-Vázquez, J. A. (2010). El problemático recorrido de la ordenación del territorio en Galicia. Cuadernos Geográficos, 47(2), 583–610.

McAlpine, C. A., Seabrook, L. M., Ryan, J. G., Feeney, B. J., Ripple, W. J., Ehrlich, A. H., et al. (2015). Transformational change: creating a safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society, 20(1), 56.

Morán-Ordóñez, A., Suárez-Seoane, S., Calvo, L., & de Luis, E. (2011). Using predictive models as a spatially explicit support tool for managing cultural landscapes. Applied Geography, 31, 839–848.

Neighbourhood Association of Chapela. (2019). Propostas para o PMUS en Chapela. Kitchener: Neighbourhood Association of Chapela.

Ronchi, S., Arcidiacono, A., & Pogliani, L. (2020). Integrating green infrastructure into spatial planning regulations to improve the performance of urban ecosystems. Insights from an Italian case study. Sustainable Cities and Society, 53, 101907.

SIOSE. (2011). Sistema de Información sobre Ocupación del Suelo de España (Spanish Land Use Information System), Ministerio de Transportes, Movilidad y Agenda Urbana, viewed 11 March 2020, https://www.siose.es/

Small, D. A., Loewenstein, G., & Slovic, P. (2007). Sympathy and callousness: The impact of deliberative thought on donations to identifiable and statistical victims. Organizational Behav- ior and Human Decision Processes, 102(2), 143–153.

Souto-González, X. M. (1993). A política territorial en Galicia: entre a expansión urbana e a percepción rural. O caso do espacio periurbano de Vigo. Minius, II-III, 199–222.

Swagemakers, P., & Dominguez-García, D. (2015). How to move on? Collective action and environmental protection in the city-region of Vigo, Spain. In International Conference Mean- ings of the Rural – between social representations, consumptions and rural development strategies (pp. 1–5). Aveiro: University of Aveiro.

Tubío-Sánchez, J. M., & Crecente-Maseda, R. (2016). Forcing and avoiding change. Exploring change and continuity in local land-use planning in Galicia (Northwest of Spain) and The Netherlands. Land Use Policy, 50, 74–82.

Valladares, F., Gil, P., & Forner, A. (Eds.). (2017). Bases científico-técnicas para la Estrategia estatal de infraestructura verde y de la conectividad y restauración ecológicas. Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente.

Note

The opinions expressed in this chapter are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNU-IAS, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent.

Open Access This chapter is licenced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO Licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to UNU-IAS, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The use of the UNU-IAS name and logo, shall be subject to a separate written licence agreement between UNU-IAS and the user and is not authorised as part of this CC BY 3.0 IGO licence. Note that the link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the licence.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation, or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.