The San Antonio Forest Key Biodiversity Area Governance Scheme: collective construction based on differences

13.12.2019

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

Corporación Ambiental y Forestal del Pacífico (CORFOPAL)

DATE OF SUBMISSION

13 December 2019

REGION

Americas

COUNTRY

Colombia (Valle del Cauca Province)

AUTHOR(S)

Quintero-Ángel, Andrés 1,2, Orjuela-Salazar, Sebastian1, Rodríguez-Díaz, Sara Catalina2, Silva, Martha Liliana 3, Rivas–Arroyo, Luz Amparo 4, Castro, Álvaro 4 & Quintero-Ángel, Mauricio 5

1 Corporación Ambiental y Forestal del Pacífico – CORFOPAL, Cali, Carrera 74 No 11A – 25 A, Zip code 760033201, Valle del Cauca, Colombia.

2 Social and Environmental Sense – SENSE, Cali, Calle 2B 66 – 56. Apt 301B. Zip code 760035132, Valle del Cauca, Colombia

3 Corporación para la Gestión Ambiental BIODIVERSA, Cali, Carrera 35 No. 3-29 piso 2 Zip code 760043, Valle del Cauca, Colombia

4 Fundación Ecovivero, Cali, Calle 9 No. 62 A-06 Zip code 760033039, Valle del Cauca, Colombia

5 Universidad del Valle, Palmira, Carrera 31 Av. La Carbonera, Zip code 763531, Valle del Cauca, Colombia

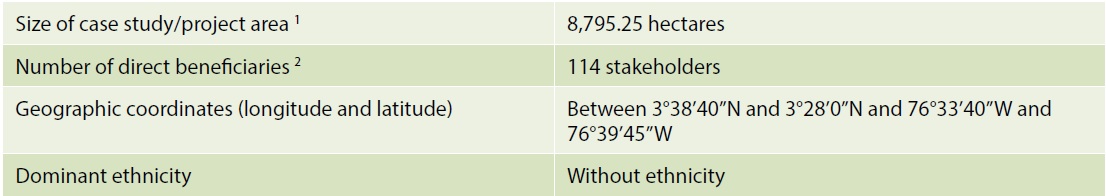

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Abstract

The San Antonio Forest (SAF) is a key biodiversity area (KBA) located in Valle del Cauca in the Colombian Andes, and one of the regions most threatened by human intervention, with less than 30 percent of its natural ecosystems conserved. This productive and biodiverse landscape is a dynamic mosaic of ecosystems and land uses, including villages, crops, forests, pastures and private properties containing luxury country houses and small farms. It is considered as a SEPLS for the reason that it generates many services important to and needed by neighboring cities and rural settlements. Even though this area connects six protected areas (one National Natural Park, three National Forest Reserves, one Forest Reserve and one Natural Reserve of the Civil Society), the laws that regulate the use and conservation of these areas are not respected. As a result, the agricultural and livestock frontiers have extended over the past few years, causing habitat loss, fragmentation and overpopulation, which in turn have increased the pollution of water sources and threatened biodiversity. However, these threats have not been properly quantified, and neither information on the status of the SEPLS, nor monitoring tools are available. In response to this problem, the Corporación Ambiental y Forestal del Pacífico-CORFOPAL and SENSE, with the support of other organizations working in the area, evaluated the resilience level of the SEPLS applying the Toolkit for Indicators of Resilience, to obtain information about the SEPLS, the communities and local stakeholders. During workshops with the different stakeholders, such as peasants, ranchers, large farmers and wealthy landowners, among others, marked differences were observed in how different stakeholders conceptualize nature and how their differing perceptions are related to their appropriation practices. Based on an understanding of these differences, we developed a governance model called the “SAF-KBA Governance Scheme”. The scheme is made up of four focus groups, with the representation of community leaders, ten locally-based NGOs that act in the four municipalities present in the SAF, private companies and government entities. This participatory scheme seeks to build a strategic and inclusive vision among the stakeholders, taking into account their different beliefs, attitudes, roles and responsibilities towards nature in order to facilitate inclusive and consensual decisions in the implementation of conservation strategies.

1. Introduction

The notion of the social construction of nature has been immersed in a debate between radical and moderate environmental constructivism (sociology) that considers nature as a social construction, and realism (philosophy) that considers nature to be provided with its own ontology existing independently of human beings. Both positions can be considered radical, because the social construction of nature can be seen as a relational process of co-evolution that takes thousands of years, and whose final result is the transformation of society in the human environment (Arias 2011).

When a society interacts with nature, it does so through the exchange (sometimes involuntarily) of matter and energy, and intentionally through the application of certain technologies and labor in order to increase the benefit of elements taken from nature (Fischer & Haberl 2007). This link with nature generates environmental impacts and a reciprocal relationship of co-evolution, which leads to a situation in which both systems depend on each other, and influence and limit each other (Singh et al. 2010).

The socio-natural interaction in the construction of the concept of nature varies according to concrete spatial-temporal or historical contexts, giving place to both positive and negative meanings or views of nature, being at times catalogued as the origin of the wealth of a country, and others as a wild and dangerous environment, where geophysical hazards such as extreme rainfall or earthquakes must be controlled (Gudynas 1999). If we look back at the medieval period (5th-15th century), nature was viewed from an organicist point of view, considered a living being of which humans were one component. On a different end, during the Renaissance period (16th-18th century in Europe), nature was regarded as the source of resources that the human being had to control and could manipulate at will. During the same centuries in Latin America, when the conquest and colonial periods were taking place, nature was viewed as an uncontrollable entity, as a wild and dangerous place due to the presence of wild animals and unknown diseases. Between the 18th and 19th centuries, there was a utilitarian vision of nature as a source of goods and materials that contribute to human development. Moving into the 19th century, the natural world started to be perceived as a machine that has its own mechanisms and operations (laws, that humans cannot violate), which allowed the field of ecology to emerge. By the end of the 20th century, nature was regarded as capital, reducing it to a factor in productive processes and integrating it into the tools and concepts available to economists (Gudynas 1999, eds. Pálsson & Descola 2001).

Moving towards the present day, in the 21st century nature has multiple faces or meanings. For some, it appears as the source of natural resources, which are used to achieve development (efficient utilitarianism vision), and for others, nature is equal to biodiversity and is viewed through its parts but also as a whole. Moreover, nature is seen as wilderness, described as an idyllic space where cooperation and symbiosis between living organisms predominate, for which it should be an example to humanity (Gudynas 1999, eds. Pálsson & Descola 2001). As for indigenous people and farmers or peasants, knowledge on the environment is valued, human beings are seen as part of nature itself, and there is a religiosity predominating towards the environment. Lastly, nowadays nature is considered an organism, and the planet constituted a system that self-regulates with emergent properties that make it a higher-level organism (Gudynas 1999, eds. Pálsson & Descola 2001). Considering this historical background, we can see that ecological processes are viewed as real, but the interpretation of these processes is built by the societies that interact with them, resulting in the construction and interpretation of nature itself (Camus & Solari 2008). Nevertheless, “nature has its own intrinsic values, independent from any human considerations of its worth or importance, and also contributes to societies through the provision of benefits to people, which have anthropocentric instrumental and relational values” (Díaz et al. 2015, p. 4).

These models, or representations of nature, are what define human action for or against nature. Likewise, they are influenced by scientific paradigms, e.g., the laws of thermodynamics were not enunciated or established until 1840-1850, and the connection between thermodynamics and evolution was not traced until the 1880s (Martínez 2005). Consequently, it was necessary to understand the different models and values of nature present among the stakeholders in the study area, in order to improve conservation and environmental management of nature and particularly of the socio-ecological productive landscape and seascape (SEPLS, defined below), as well as its governance. The latter is fundamental to better understand how environmental decisions are made and whether resultant policies and processes lead to environmentally and socially sustainable outcomes (Bennett & Satterfield 2018). In this context, this study aims to document the development of a participative governance scheme for the SEPLS present in the San Antonio Forest Key Biodiversity Area (SAF-KBA), which integrates the different visions of nature held by the main stakeholders.

1.1 Description of San Antonio Forest – Key Biodiversity Area

The San Antonio Forest (SAF) Key Biodiversity Area (KBA), part of the Paraguas-Munchique corridor, is one of the 31 Hotspots of the Tropical Andes of Colombia and one of the regions most threatened by human intervention, with less than 30 percent of its natural ecosystems conserved (Etter & Van-Wyngaarden 2000; Kattan 2002). This area in particular is prioritized by its very high species richness, their high level of endemism, and because some of these species are threatened with extinction (Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund-CEPF 2015).

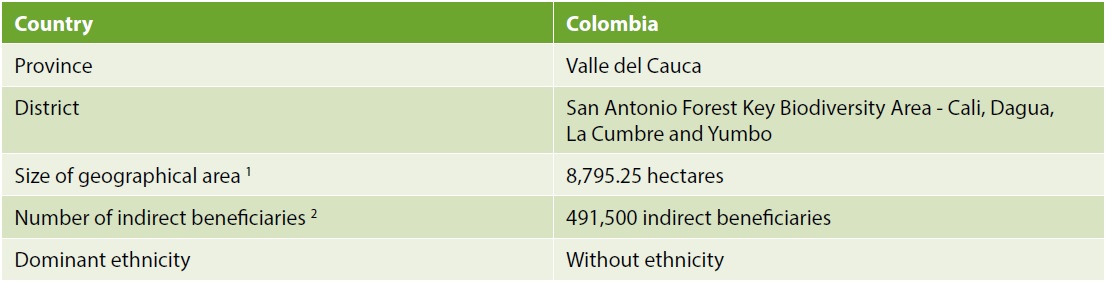

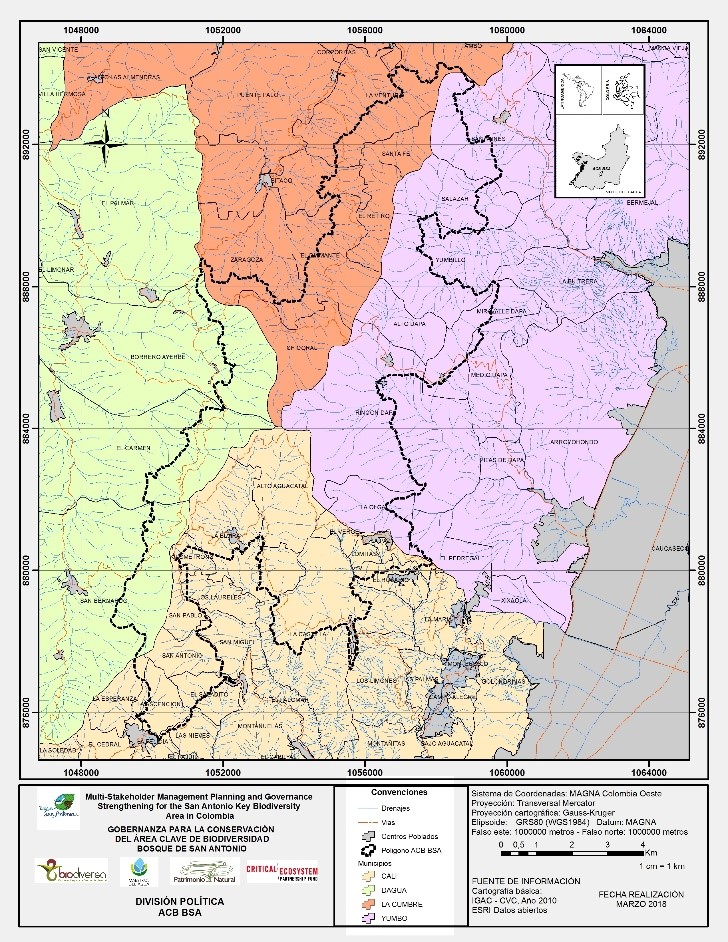

Comprising an approximate area of 8,795 hectares, the SAF-KBA is located on the northern side of South America, in Southwestern Colombia, on the eastern flank of the western Andean Cordillera (system of mountain ranges) in the Department of Valle del Cauca (see Fig. 1). It is under the jurisdiction of the municipalities of Cali, Dagua, La Cumbre and Yumbo (see Fig. 2), and comprises the area between grades 3°38’40” and 3°28’0″ North latitude and 76°33’40” and 76°39’45” West longitude, with an altitudinal range between 1,700 and 2,150 meters. Three types of climates and humidity provinces predominate in the area: cold thermal floor and humid province, medium thermal floor and humid province, and medium thermal floor and dry province, defined by the gradient altitude and the influence of the Pacific, determinants of the great diversity.

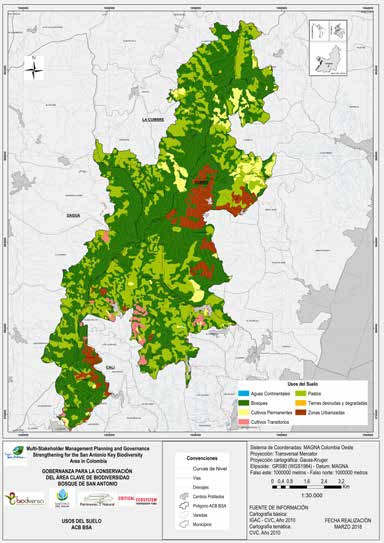

The SAF-KBA is a dynamic mosaic of ecosystems and land uses, including villages, crops, forests, pastures and private properties with country houses and small farms, and therefore is considered to fall under the category of socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes – SEPLS (UNU-IAS, Bioversity International, IGES & UNDP 2014) (see Fig. 3). It provides important ecosystem services for the surrounding human settlements, including Cali, the capital of Valle del Cauca, as well as the Dagua, La Cumbre and Yumbo municipalities. It is also important because it connects six protected areas that the polygon-shaped area overlaps: the Farallones National Natural Park, the National Forest Reserve of Cali, the National Forest Reserve Cerro Dapa Carisucio, the National Forest Reserve of La Elvira, the Forest Reserve of Bitaco, and the Jurásico Natural Reserve of the Civil Society. However, the law is not respected and the agricultural and livestock frontiers have extended over the past few years, causing habitat loss and fragmentation, thus polluting water sources and threatening biodiversity.

1.2 Socioeconomic characteristics of the area

The distribution of the population in the SAF-KBA SEPLS reflects the disparity between the municipalities of Cali and Yumbo (, where the population is concentrated in urban areas, and the municipalities of Dagua and La Cumbre, where population is concentrated in rural areas . Thus, there are two densely urbanized municipalities, with a large demand for environmental services, especially water, for their populations and that of the productive sectors, and also rural populations that require access to the same services.

Although a large part the SAF-KBA is regulated through the protected areas present in the polygon, there are still conflicts over land use. Productive activities in the municipality of Dagua focus mainly on livestock, agriculture and tourism. In the municipality of La Cumbre, livestock is the basis of the economy, as well as permanent crops such as tea (see Fig. 4), coffee, flowers and some transient crops such as vegetables and spices; however, the precarious road network makes it difficult to market these products. There is a trend towards increased land parcelling for recreational use, resulting in an increase of the floating population. If we look at the municipality of Yumbo, subsistence crops and livestock predominate, and the number of recreational homes has climbed in the past years. Finally, in the Cali municipality, livestock and temporary crops, mainly aromatic and spices, are the main economic activities, along with coal mining in some sectors. The tendency to convert properties for recreation and the adaptation of tourist sites is also booming over the whole area. Ecotourism stands out, motivated by birdwatching and hiking activities.

2. Methodology

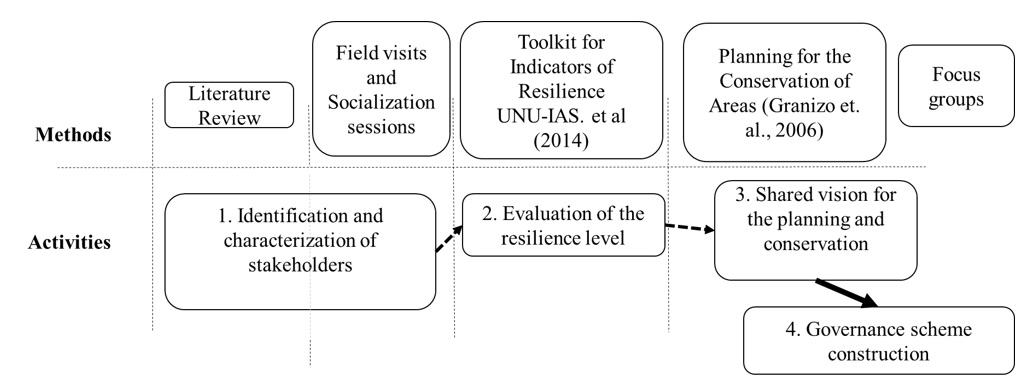

Taking into account the aim of the study, to construct a participative governance scheme that represents the different visions of nature held by the SAF-KBA stakeholders, we designed and implemented a four-step method (see Fig. 5). We first obtained historical information through the review of literature regarding the study area and the social processes that have shaped it into the present SEPLS. We then visited the field and organised socializing sessions, where we identified and became familiar with the stakeholders, and introduced the project to them. Third, we undertook a process to develop a conservation plan (Granizo et al. 2006) tailored to the needs of the study area and the stakeholders that inhabit it. Finally, we conducted four focus group discussions with 10 to 20 community leaders respectively. These groups played a key role in the construction of the SAF-KBA governance scheme.

2.1 Identify and characterize stakeholders

We identified the main stakeholders, both community and institutional (i.e. government institutions, such as municipal mayoralties and regional environmental authorities), prior to introducing the project and engaging them in the process. We identified stakeholders in the four municipalities that make up the SAF-KBA SEPLS through field visits and a review of information provided by the institutional stakeholders that work in the territory. Likewise, we reviewed secondary information in the form of documents and studies, particularly those produced by organizations that have worked in the area and that could contain information, either of a technical nature and/or about the stakeholders. On the other hand, we took into consideration the contributions of each one of the institutional and community stakeholders regarding the socio-environmental conditions of the territory, as well as their level of interest in participating in the project during the socializing sessions.

2.2 Evaluate the resilience level of SAF-KBA SEPLS

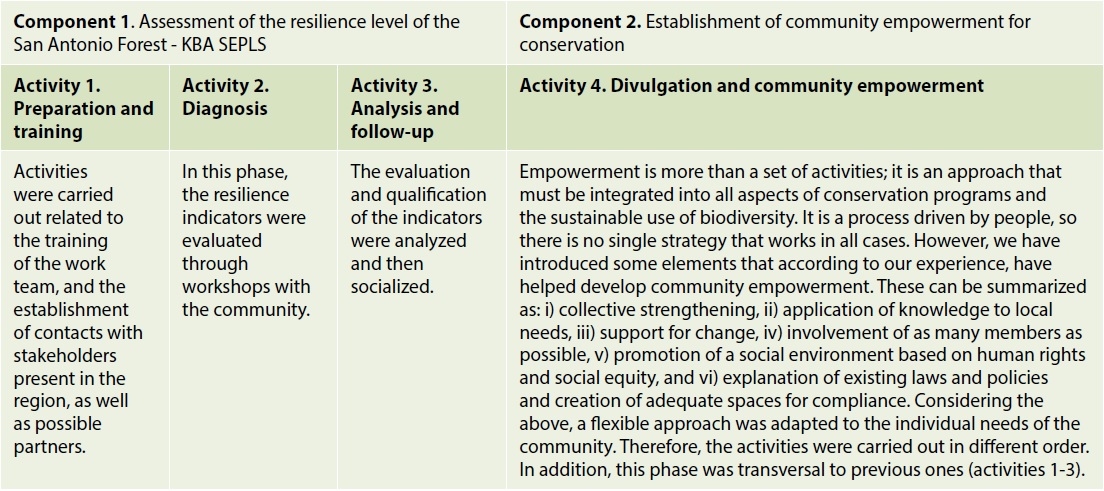

We evaluated the resilience level of the SEPLS using the Toolkit for Indicators of Resilience (UNU-IAS, Bioversity International, IGES & UNDP 2014), that provides a subset of 20 indicators to assess the trends and level of resilience of the study area. We then moved to implement four key activities, that are grouped under two major components (see Table 1). The two major components are: i) assessment of the resilience level of the study area, which includes preparation, training, diagnosis and analysis of the indicators (activities 1-3), and ii) community empowerment for conservation, that consists of activity 4, divulgation and community empowerment. This last activity embodies an approach that needs to be integrated into all aspects of conservation programs and sustainability, and that was addressed transversely to activities 1-3. Community empowerment was key to linking people with nature for conservation and for encouraging them to think about resilience, as it connects local knowledge and needs with policies and conservation goals.

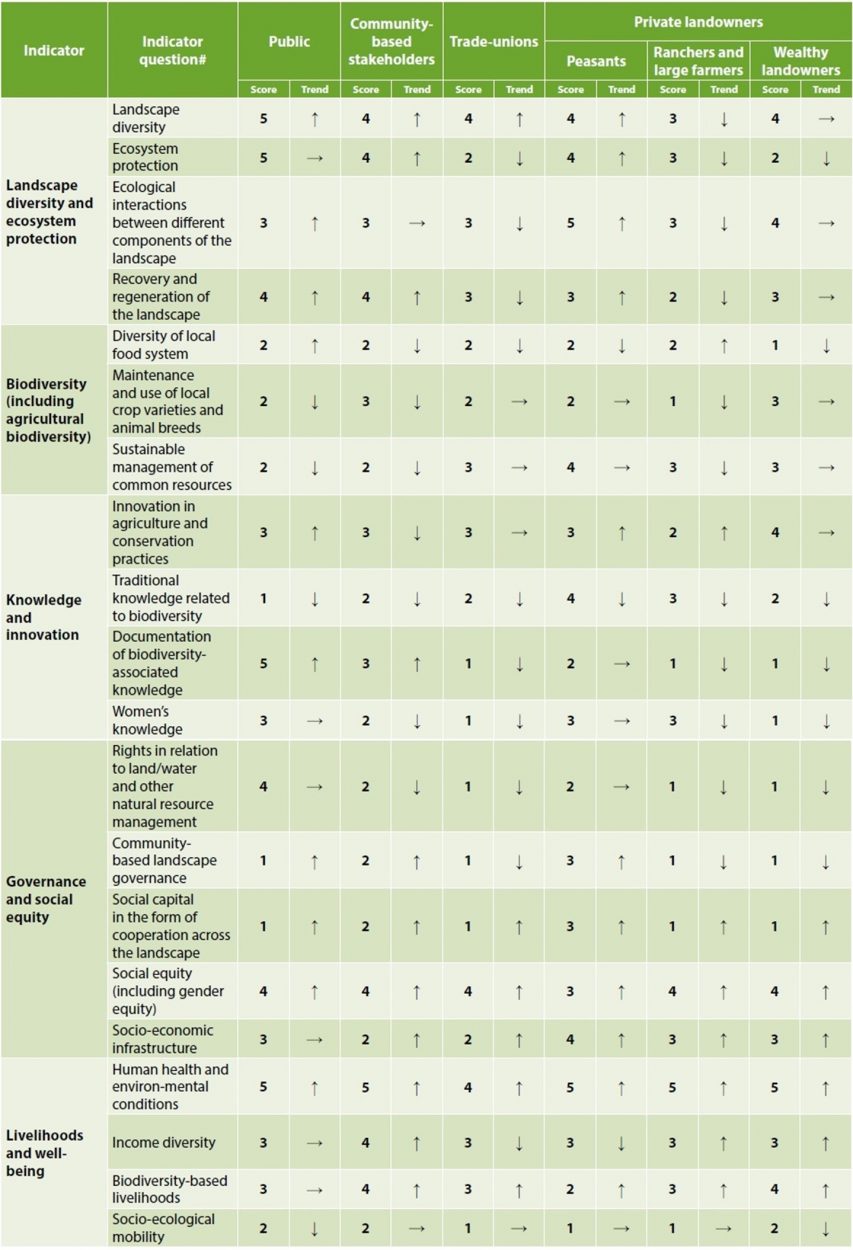

The resilience indicators, as mentioned above, have 20 subsets falling under five categories: i) landscape diversity and ecosystem protection; ii) biodiversity; iii) knowledge and innovation, including agricultural biodiversity, iv) governance and social equity; and v) livelihoods and well-being. In activity 2, we asked community members to rate the state of the indicators using a five-point scale: (5) Very high, (4) High, (3) Medium, 2) Low, and (1) Very low. We also asked them to evaluate trends using three categories: ↑ Upward trend, → No change, and ↓ Downward trend. We implemented this activity with the support of our partner, an NGO called Social and Environmental Sense (SENSE), as well as that of other organizations working in the area.

2.3 Shared vision for the planning and conservation of the SAF-KBA SEPLS

During the workshops (see Fig. 6) with the different stakeholders, such as peasants, ranchers, large farmers, and wealthy landowners, we identified marked differences in the way they conceptualized nature, their relationship with nature and the sustainable practices they implement. Based on these differences, we searched for common points to build a shared vision for the planning and conservation of nature and biodiversity of the SAF-KBA SEPLS, with the goal of improving the protection of this important area through a participative and collaborative planning exercise between the community, public stakeholders (government), and cross-sectoral stakeholders.

2.4 The SAF-KBA SEPLS Governance Scheme

Prior to the evaluation of resilience levels, the Corporation for Environmental Management BIODIVERSA advanced the planning process for managing the SAF-KBA SEPLS using the “Planning for the Conservation of Areas” methodology (Granizo et al. 2006) for the design and management of this conservation area, based on a diagnosis and an integrity analysis of the definition of conservation objects that were carefully selected with the accompaniment of experts. This activity produced knowledge about the area and reconnected it with the expectations of the local stakeholders in each municipality, as well as with the institutional stakeholders.

Using this information and understanding of the differences in the way of conceptualizing nature and the shared vision for the planning and conservation of the nature of the SAF-KBA SEPLS, we have developed a governance model, which we call the “SAF-KBA Governance Scheme”. This scheme is based on norms, concepts and policies at national and international levels, such as: the right of petition (as a fundamental right in the Colombian Constitution) and participation mechanisms; the ordering of the territory; the generation of knowledge with the management of information and incentives for conservation to strengthen the exercise of governance by the institutions; the political empowerment of the community base; financial sustainability by the guilds and human well-being of the owners of the properties; the communities’ identity, freedom, health, safety, and material goods in relation to biodiversity and ecosystem services; and the processes of ecosystem functioning and climate change.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of stakeholders and differences in the way of conceptualizing nature

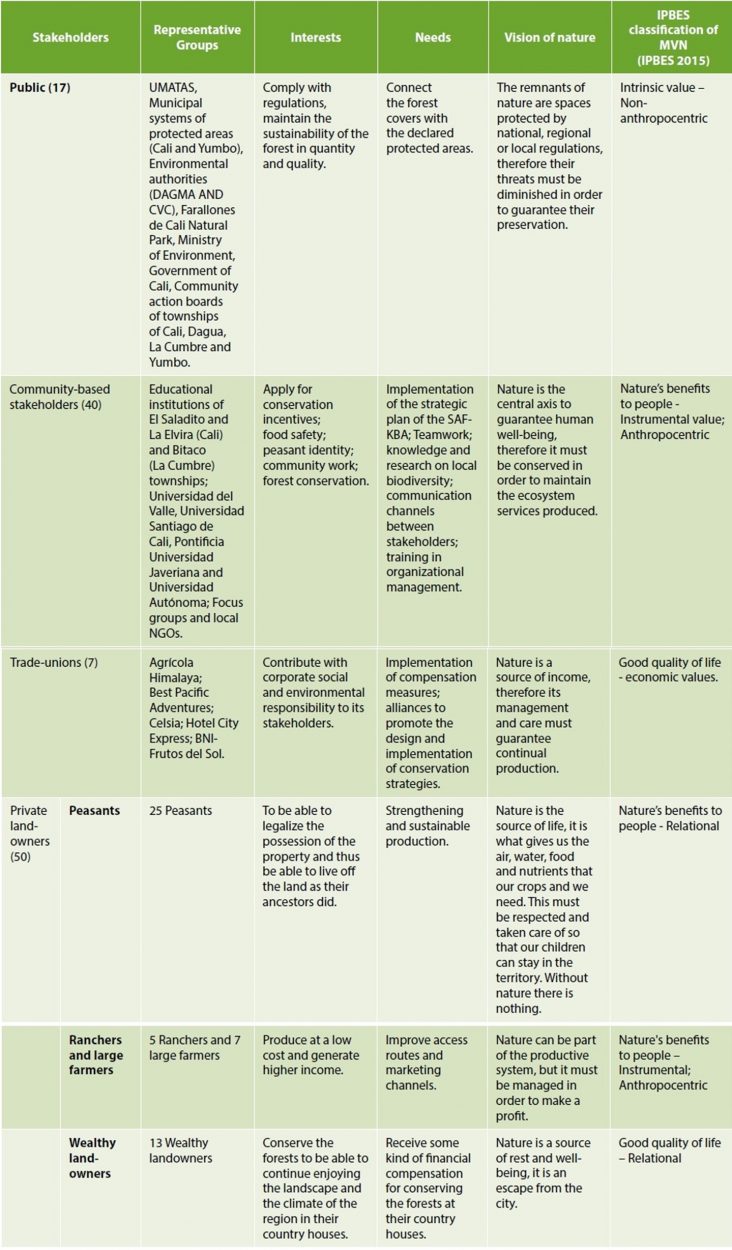

We identified 17 public stakeholders, 40 community-based stakeholders, seven unionists and 50 private landowners (people who own an area of land and give various uses to it; some make their livelihoods from it, while others just use it recreationally) as the main stakeholders of the SEPLS in the SAF-KBA. We divided the 50 private landowners into three categories based on their educational, sociocultural and socioeconomic backgrounds: i) peasants, ii) ranchers and large farmers and iii) wealthy landowners (who use the land mainly to build country houses, but their livelihoods do not depend on the productivity of the land). The results we obtained from the characterization of stakeholders and the differences in the way of conceptualizing nature are summarized in Table 2, showing the representatives of each group of stakeholders, their interests, needs, and visions of nature. The latter corresponds to multiple values of nature and its benefits (IPBES 2015), such as recognition of the intrinsic value of nature by public entities that are concerned with ecosystem conservation, or as the instrumental value assigned by community-based stakeholders, ranchers and large farmers, who recognised nature’s benefits to people for production. Also noted are the economic values trade-union stakeholders recognise in nature, seeing it as a source of income, therefore making its management and care fundamental to guarantee its continuous production. Furthermore, the good quality of life—relational value given by wealthy landowners who consider nature to be a source of rest and well-being, and the relational values peasants hold, who consider nature as a source of ecosystems services that benefit people, are among other values that assign a multitude of roles to nature in its interaction with human societies.

These multiple values of nature and its benefits, as assumed by stakeholders, correspond to different nature models or visions and determine the actions or possible actions against nature in the SAF-KBA SEPLS. According to Díaz et al. (2015), the value of nature’s benefits to people varies among individuals, within groups, and across groups at various temporal and spatial scales. For instance, the value of the vegetation and soils of watersheds in filtering water for drinking will vary when there is no built alternative (e.g. a water filtration plant). Stakeholder perceptions are transformed into values of nature in accordance to their environmental rationale. The latter can be understood as the implication of reason in the meaning of actions against the environment, which stages the capacity that guides and directs the action of stakeholders (González n.d.). This environmental rationale and the associated values of nature help define what a society perceives as important, beneficial or useful in search of achieving a good quality of life (Díaz et al. 2015).

The productive and extractive activities of some stakeholders in the SAF-KBA SEPLS, together with their rationale, as well as State and private-sector actions that promote these activities, show a real and potential conflict between conservation and development in the planning for the territory (Quintero-Ángel 2015). The two environmental rationales, the predatory (trade-unions, ranchers and large farmers) and the alternative (oriented to the conservation of nature, held by farmers, community-based stakeholders and wealthy landowners), present in the SAF-KBA SEPLS, are closely associated with the vision of development that western modernization imposes, which according to Toledo, Alarcón & Barón (2009):

[…]establishes as the only referent the bipolar scheme between “tradition” and “modernity”, explained solely in function of the productive and economic (and sometimes social and cultural) aspects and that proposes rural development as the productive transformation of “traditional” peasant, or preindustrial ways into agro-industrial or “modern” modalities, both in its state-socialist version and in its free market version (p. 341).

Even though both rationales relate to the environment, they do so in a different way: one is a predatory relationship in which human beings profit from nature to satisfy their needs and desires without considering or respecting it, and the alternative is a relationship where human beings also serve the ecosystems. The latter is associated with a cosmic worldview and conception of nature with an ethical consideration of no-abuse in the use of nature (Quintero-Ángel 2015).

3.2 Evaluation of the resilience level of the SAF-KBA SEPLS

In the evaluation workshops on the level of resilience, participants evaluated the indicators individually and subsequently discussed within the group to reach consensus among each of the interested parties (see Table 3). In these workshops, 69 of the participants were women (65%), and 38 were men (35%). Below, we present the results obtained for the SAF-KBA SEPLS, grouped into five strongly-interrelated areas..

3.2.1 Landscape diversity and ecosystem protection

Regarding the diversity of the landscape, most of the stakeholders recognize the great diversity present within the SAF-KBA SEPLS, as well as the fact that the presence of patches of cloud forest, riparian forests and the variety of microclimates, make this area more resilient to external shocks. According to Pascual et al. (2017), the variety of views and values associated with nature’s goods and services gives place to diverse points of view in relation to areas such as conservation, resilience, equity and ways to accomplish sustainable development goals, but this diversity of views is rarely acknowledged or taken into account when making decisions.

As for the protection, recovery and regeneration of the landscape of this area, results are uneven. For public and community-based stakeholders, the SAF-KBA SEPLS is protected because it overlaps with protected areas of national order; however for the peasants, the protection of the SAF has taken place for a different reason. For them, the recovery and protection of forest areas is due to the fact that many old people who used the land have died, and young people have moved to the cities (mainly to Cali). The younger generation does not engage in the peasant vocation, so the lands that were productive 40 years ago are now secondary forests. From the viewpoint of the productive sector (trade-unions, ranchers and large farmers), the protection status of the area is low and shows great deterioration. This may be due to the fact that land use is restricted for some productive activities inside the protected areas, meaning that these stakeholders have frequent negative interactions with environmental authorities, a factor that can polarize responses.

According to the wealthy landowners, the area is deteriorating as the dynamic mosaic of ecosystems and land uses, including villages, crops, forests, pastures and private properties with country houses and small farms becomes increasingly evident, due to the increase of a floating population. For most stakeholders, the ecological interactions between different components of the landscape were not clear. Most gave an intermediate rating with a clear tendency mainly because the forests protect water sources. Still, the peasants recognize that the forests not only protect the water sources, but also benefit other areas through pollination, pest control, and an increase of animal population.

3.2.2 Biodiversity (including agricultural biodiversity)

In terms of biodiversity, all stakeholders recognize the great richness of fauna and flora species of the region, especially birds—in the SAF-KBA SEPLS polygon alone, 357 species of birds have been recorded (BIODIVERSA 2018). Nonetheless, in terms of agricultural biodiversity, most stakeholders agree that it has been lost over time, which may be due to the migration of local farmers to the city or the arrival of foreigners. Nonetheless, aromatic crops and medicinal plants are mainly maintained in the area. Maintenance and use of local crop varieties and animal breeds does take place, but only among some peasants who call themselves seed keepers. In this sense, these types of practices should be promoted to conserve the genetic diversity found in local crop varieties and animal breeds, which is important because it confers resilience to the SEPLS in the climate change scenario.

Regarding sustainable management of common resources, ratings are low mainly due to the fact that most common resources, such as forests and water sources, are located within private properties. The situation of the water sources that supply farms is probably the most complicated, since by law water sources belong to the State (Decree 1076 of 2015). However, located inside farms and properties with country houses, access to this resource is difficult in some cases. In some parts of the SAF-KBA SEPLS, there are water concessions legally established by the environmental authority regulating the quantity and flow taken. Yet in other cases there is conflict, generating a so-called war of the hoses, which involves of the connection of many hoses to the same stream, where the one that takes more water is the one that has more economic resources and can pay for a longer or bigger hose that takes up more water.

3.2.3 Knowledge and innovation

On innovation in agriculture and conservation practices, neither the qualifications nor the trends given by stakeholders are completely uneven, which can be explained by the large number of people interested in the preservation of the SAF-KBA SEPLS (international funds, more than ten NGOs including local and regional, universities and inhabitants in general). In addition, the generation of income from nature tourism, or simply from the tourist attraction that the change of landscape and climate just 20 minutes away from the city of Cali represents, makes those involved in this practice keep innovating in terms of conservation strategies and sustainable production methods.

Regarding traditional knowledge, innovating and learning practices in the SAF-KBA SEPLS are being lost. This loss occurs for various reasons, among the most outstanding are those already mentioned (migration to the city and little interest in the peasant vocation), but it is largely attributed to the absence of elders that can transmit traditional knowledge to the floating population and the remaining peasants. Thus, it is not uncommon to find that all stakeholders have qualified the trend downwards, a factor that confirms that these practices are being lost.

For public and community-based stakeholders, the documentation of biodiversity-associated knowledge is doing well and on an increasing trend because management plans for the protected areas are present in the SEPLS, and also due to numerous studies in various related topics in the area. For example, the study of birds in the area has been researched for over 100 years (Kattan, Álvarez-López & Giraldo 1994; Kattan et al. 2016). For the remaining stakeholders, scores are low with a downward trend due to the fact that such publications are not known, or are written in a scientific manner and even in other languages, such as English.

Women’s knowledge, experiences, and skills are recognized between medium and very low scores and present a downward trend. While it is still recognized that women hold knowledge of medicinal and aromatic plants (which are traditional crops), the fact that girls and young women are not very interested in learning these practices puts this knowledge at risk. When qualifying this indicator, women (on average 65% of workshops participants) changed their way of qualifying (in the individual case) positively and with a tendency to improve by lower scores and a negative trend, which can be understood as a search for recognition. This result is particularly curious considering that during discussions and group work, it was almost always the women who directed and clearly presented their position.

3.2.4 Governance and social equity

The classification of indicators grouped in this area is very uneven, due to the legal land tenure problem of the majority of peasants. As already mentioned, most of the land belongs to wealthy landowners who live in the city and have their country houses in the SEPLS. In addition, conflict exists with the national protective forest reserves present in the SEPLS, because although these protected areas do not put restrictions on the property, they do restrict some uses. Thus, many economic activities are incompatible with these protective institutions.

For community-based landscape governance and social capital in the form of cooperation across the landscape, scores are low, but the trend is toward improvement. This is because alliances have been created to seek effective governance of the SAF-KBA SEPLS. This can be evidenced by the technical board of the SAF that is connected to nine NGOs and that, together with the participation of other stakeholders, has created the SAF-KBA governance scheme.

The social equity (including gender equity) indicator is one of the most similar in qualification and trend. In this sense, the rights and access to resources and opportunities for education, information and decision-making are fair and equitable for all community members, including women, as evidenced by the great participation of women in the workshops.

3.2.5 Livelihoods and well-being

According to our results, socio-economic infrastructure in the SEPLS has an intermediate qualification and a tendency to improve. This evaluation is due to the existence of rural schools in the area, as well as health centres, safe drinking water, electricity and communication infrastructure. The only aspect requiring improvement in some sectors is the roads. The indicator for “human health and environmental conditions” has the best rating with a tendency to improve. People are very healthy because of the good weather and good air quality. For the indicator on income diversity, scores fall in the middle. Although many traditional forms of income have been lost, such as work in growing certain crops, there are new opportunities for income with the development of activities related to tourism.

For biodiversity-based livelihoods, scores range from high to low—high for those who are finding new ways to obtain income based on biodiversity, such as eco-tourism and birdwatching, and low for the peasants who used to have a close relationship with biodiversity, but with the loss of cultural identity during the last decade, also lost this relationship. Socio-ecological mobility, according to the stakeholders, is low and very low, given that most agree that there are no opportunities for mobility.

3.3 Shared vision for the planning and conservation of the nature of the SAF-KBA

According to Leff (2004), the environmental crisis is crisis of the ways of understanding the world. Since the human being is as an animal endowed with language, human history is separate from natural history. Thus natural history is the meaning assigned by words to things, generating strategies of power in theory and knowledge that have disrupted reality to forge the modern world system.

Therefore, the social construction of a solution to the environmental crisis that affects the modern world must be focused on a shared vision of the stakeholders interested in, or involved in, the problem. The construction of a solution must start from the points they (involved communities and stakeholders) have in common.

In this sense, the existing similarities and differences among the stakeholders’ opinions were evaluated. The main similarities or factors that stakeholders had in common were searched out to allow for the integration of a shared vision of nature for the SAF-KBA SEPLS. In this case, we found that for all stakeholders, nature is the source of life and the central axis to guarantee human well-being and production of income. Therefore, nature must be respected, taken care of, conserved and well managed in order to maintain the ecosystem services that it produces.

With this in mind, in order to guarantee the conservation of the SAF-KBA SEPLS, the ecological integrity of the present ecosystems must be ensured through the improvement of connectivity and the reduction of pressures that lead to fragmentation and deteriorate the quality and quantity of ecosystem services.

Figure 7 (a and b). Examples of the conservation objectives in the participatory governance, a) Colombian Night Monkey (Aotus lemurinus)

(Photo: Armin Hirche); b) Ruiz’s robber frog (Strabomantis ruizi) (Photo: Oscar Cuellar)

3.4 The SAF- KBA Governance Scheme

The SAF-KBA governance scheme is based on both national and international concepts, norms and policies, such as petition rights, territory ordering, incentives for conservation, and management of information to strengthen institutional governance. It also involves actions to empower the communities, achieve financial sustainability, secure and improve ecosystem functioning and mitigate and adapt to climate change. The governance scheme seeks to build a strategic and integrated vision among stakeholders, to ensure inclusive and consensual decision-making and implementation of conservation strategies.

Considering the above, the governance scheme is a shared management tool in the holistic construction of SAF-KBA conservation strategies for implementation, with balance between the State, civil society and the economic sector, and in line with the personal attitudes of the community through agreements and consensual alliances between the stakeholders. This political exercise is based on environmental and social sustainability, and validated by the principles of good governance of IUCN for protected areas: 1. Legitimacy and Voice: participation and search for consensus; 2. Direction: strategic vision; 3. Performance: ability to respond effectively and efficiently; 4. Responsibility and Accountability: transparency; and 5. Justice and Rights: equity and law enforcement (ed. Dudley 2008).

The scheme seeks to build, in each component, a strategic and integrated vision among all stakeholders, taking into account their different roles and responsibilities, as well as ensuring inclusive and consensual decision-making for the implementation of conservation strategies. This aim is combined with the objective of maintaining and improving the resilience of socio-ecological systems at local and regional scales, considering scenarios of change and through joint, coordinated and concerted action by the State, the productive sector and civil society.

Accordingly, the objective of participatory governance is to conserve and recover biodiversity along with its ecosystem services, with emphasis on the connectivity of the landscape and the ecological integrity of the selected conservation objectives: 1) natural forest cover; 2) water system and edaphic system; 3) community of insectivorous and frugivorous birds; 4) the amphibian community; 5) the multicolored tanager (Chlorochrysa nitidissima); 6) the Colombian Night Monkey (Aotus lemurinus) (see Fig. 7a), a threatened species prioritized for the SAF-KBA; the cerulean warbler (Setophaga cerulea); and the Ruiz’s robber frog (Strabomantis ruizi) (see Fig. 7b).

The governance scheme is compiled in a technical document, structured into seven interrelated components: 1. characterization of actors and socio-economic activities; 2. participatory diagnosis of the territory; 3. administrative structure; 4. game rules and safeguards; 5. strategic planning and monitoring (which addresses the following topics: conservation and restoration, use and sustainable management of biodiversity with its ecosystem services, knowledge and research, empowerment, and joint and shared co-management); 6. implementation of the financial sustainability plan; and 7. continuous improvement. The components are adhered to a legal and conceptual framework as well as to the mechanisms or instruments of political participation, the ordering of the territory, the generation of knowledge, the information systems, communication strategies, and to the incentives for the conservation of biodiversity with its ecosystem services.

In the “Strategic Planning and Monitoring” document, goals were set to be fulfilled between 2018 and 2028, which is consistent with the social, business and environmental responsibilities of the different stakeholders of the SAF-KBA SEPLS. The main goals are: 1) to restore 600 hectares in river protection zones; 2) to secure 50 private properties with incentives for conservation; 3) to develop mitigation and adaptation measures to climate change and establish them in five localities within the SEPLS; 4) to establish a biological corridor connecting with the NNP Farallones de Cali for forest compensation certified by the Colombian Institute of Technical Standards; 5) to continuously train the community and decision-makers through specific programs; and 6) to implement five green- business projects.

As part of the governance scheme, two fundamental structures were created: 1) the four focus groups (one for each municipality present in the SAF-KBA SEPLS), with community leaders as representatives, that are connected with the Municipal Agricultural Technical Assistance Units (UMATAs for its name in Spanish), Municipal Planning Secretariats, the environmental authority, trade or business associations and other public entities such as schools or universities (see Fig. 8), and 2) the technical board, constituted by nine locally-based NGOs (see Fig. 9) that have been working in this area for some years and that are members of the departmental system of protected areas SIDAP Valle del Cauca (Corporación Biodiversa, CORFOPAL, Maestros del Agua, SENSE, Dapaviva, Ecotonos, Ecovivero, Asociación Río Cali y Fundación Agrícola Himalaya). These organizations are connected to different stakeholders (local communities, NGOs, private companies and some government entities) with recognition of differences and mutual respect. In addition, ongoing virtual communication and meetings are carried out. Each player serves a different role within the governance strategy. Community-based stakeholders (local NGOs) help establish management strategies among the communities, and institutional stakeholders (government entities) represent governance and policies. Likewise, private landowners (community leaders) have a role in implementing conservation strategies, and trade-unionists (private companies) are involved in the financial supporting aspect.

Among the scheme’s main achievements since its establishment in 2018 is the signing of voluntary agreements for the conservation and shared management of the SEPLS in the Alliance for the Conservation of SAF-KBA, the management of payments for environmental services (PSA for its initials in Spanish) of the focus group of Cali and private landowners with the Department of Administrative Management of the Environment, DAGMA (the environmental authority of the municipality of Cali), and the award received from the Call for the Recognition of Local Conservation Areas and Complementary Conservation Strategies, for contributions to the improvement of the conditions of Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru to conserve biodiversity through effective and equitable management of protected areas and other conservation measures. Implementation was carried out by the German development agency GIZ, the International Council for Local Environment Initiative-ICLEI and the International Union for Conservation of Nature-IUCN, with international support from the International Climate Initiative-IKI, the Federal Ministry of the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) and the Ministry of Environment in Colombia.

4. Lessons learned and conclusion

These results allow us to infer that while interactions between stakeholders and nature do depend on the particular interests of the respective stakeholder groups, above all these interactions depend on the gender and the educational, sociocultural and socioeconomic levels and backgrounds of the stakeholders involved. One of the main lessons we have learned through previous work is that in this type of exercise, it is fundamental to guarantee the participation of different stakeholders in the territory in the execution of the project, since they are the ones that provide the most accurate information on the social and environmental situation of the territory and contribute to the definition of the most appropriate routes for applying the Toolkit for Indicators of Resilience. In this sense, we carried out an analysis of stakeholders based mainly on qualitative information collected from the available participating persons in order to: i) determine their interests in relation to the political proposal or to projects (be it a research project, a development project or an information policy proposal); ii) identify the key stakeholders that exert a greater influence via their power or leadership; and iii) determine the most important issues or points for the design, development and implementation of the project.

Ongoing challenges for the SAF-KBA governance initiative, with the agreements and alliances between the stakeholders, include the creation of a culture for the conservation of biodiversity and its ecosystem services, and securing the positioning and integral welfare of the individuals, representing the community. In order to face these challenges, the continuous promotion of community empowerment is required, which will be addressed through follow-up in the focus groups and on the technical board within the programs and projects established in the governance scheme, as well as in the Alliance for the Conservation of SAF-KBA, which established specific goals to address these challenges.

Likewise, understanding the models or representations of nature held by the stakeholders in a SEPLS is very important to consolidate governance processes. If different visions are not understood and considered in the construction of a shared vision, the conservation objectives and the actions of the stakeholders can differ, leading to major conflicts associated with environmental rationale related to human welfare. In the same way, those who work in the governance of the SEPLS will be able to contribute to contexts such as the SAF-KBA, not only through understanding the forms of appropriation of nature and derived environmental conflicts, but also by promoting decision-making by different stakeholders to find more sustainable forms of appropriation of nature, which allow for the conservation of ecosystems, as well as the well-being of their inhabitants, key factors that contribute to the conservation of the SEPLS and its continuity over time.

The main challenge we faced when constructing the shared vision was reconciling the differences in the way stakeholders relate to nature; these rationales were at times almost opposed to one another, making it difficult to find common points. Furthermore, the relationships of power over diverse goods of nature, and the sense of ownership over a particular value, in addition to a general lack of trust in the environmental authorities, were hurdles that had to be overcome in order to build a shared vision of nature in the SEPLS.

Finally, the conflicting visions and changes in nature models in the SAF-KBA SEPLS can be managed in the proposed new governance scheme, maintaining the participatory processes in the focus groups and the technical board. This approach will recognize, make visible, and respect the diverse values of stakeholders and address the power relations through which these are expressed (Cundill & Rodela 2012). Additionally, considering the diversity of worldviews and values of nature may lead to an iterative approach to identification of policy objectives and instruments in the governance scheme (Pascual et al. 2017).

Acknowledgements

This publication is the result of joint work among projects: 1) Resilience level assessment of the San Antonio Forest / KM 18 Key Biodiversity Areas and community empowerment on conservation funded by The Satoyama Development Mechanism (SDM) 2017 grant; and 2) Multi-stakeholders management planning and governance strengthening for the San Antonio Forest Key Biodiversity in Colombia funded by The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) agreement 66493 of 2017. The authors thank all the stakeholders of the SAF-KBA SEPLS, especially the four focus groups and the organizations that are part of the technical board of the SAF and to Adelita San Vicente Tello, Kuang-Chung Lee, Polina G. Karimova, Shao-Yu Yan, the IGES Team and the SITR5 editors team for the final revision of this document.

References

Arias, M 2011, ‘Hacia un constructivismo realista: de la naturaleza al medio ambiente’, ISEGORÍA. Revista de Filosofia Moral y Política, no. 44, pp. 285–301.

Bennett, NJ & Satterfield, T 2018, ‘Environmental governance: A practical framework to guide design, evaluation, and analysis’, Conservation Letters, vol. 11, no. 6, e12600.

BIODIVERSA 2018, Un documento diagnóstico de información biológica, biofísica, usos de suelo, socioeconómico y marco normativo-jurídico del ACB BSA elaborado y socializado a los actores a noviembre de 2018.

Camus, P & Solari, ME 2008, ‘La invención de la selva austral. Bosques y tierras despejadas en la cuenca del río Valdivia (siglos XVI- XIX)’, Revista de Geografia Norte Grande, vol. 40, pp. 5–22.

Cundill, G & Rodela, R 2012, ‘A review of assertions about the processes and outcomes of social learning in natural resource management’, Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 113, pp. 7–14.

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund 2015, ‘Ecosystem profile: Tropical Andes biodiversity hotspot’.

Díaz, S, Demissew, S, Carabias, J, Joly, C, Lonsdale, M, Ash, N, … Zlatanova, D 2015, ‘The IPBES Conceptual Framework — connecting nature and people’, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 14, pp. 1–16.

Dudley, N (ed.) 2008, Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, with Stolton, S, Shadie, P & Dudley, N 2013, IUCN WCPA Best Practice Guidance on Recognising Protected Areas and Assigning Management Categories and Governance Types, Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 21, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Etter A & van-Wyngaarden W 2000, ‘Patterns of landscape transformation in Colombia, UIT emphasis in the Andean Region’, Ambio, vol. 29, no. 7, pp. 432-9.

Fischer, M & Haberl, H 2007, Socioecological Transitions and Global Change: Trajectories of Social Metabolism and Land Use, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

González-Rodríguez, G 2014, ‘El precomún como imaginario social. Sostenibilidad, decrecimiento y ética de la mesura’, Estudios filosóficos, vol. 63, no. 184, pp. 455-474

Granizo, T, Molina, M E, Secaira, E, Herrera, B, Benítez, S, Maldonado, O, …Castro, M 2006, ‘Manual de planificación para la conservación de áreas, PCA’, TNC & USAID, Ecuador.

Gudynas, E 1999, ‘Concepciones de la naturaleza y desarrollo en América Latina’, Persona y Sociedad, vol. 13, pp. 101–25.

IPBES 2015, Preliminary guide regarding diverse conceptualization of multiple values of nature and its benefits, including biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services (deliverable 3 (d)), Plenary of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Fourth session.

Leff, E 2004, Racionalidad ambiental. La reapropiación social de la naturaleza, SIGLO XXI, México.

Kattan, GH, Álvarez-López, H & Giraldo, M 1994, ‘Forest fragmentation and bird extinctions: San Antonio eighty years later’, Conservation Biology, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 138-46.

Kattan, GH 2002, ‘Fragmentacion: patrones y mecanismos de extinción de especies’, in Ecología y conservación de bosques tropicales, eds MR Guariguata & GH Kattan, Ediciones LUR, San José.

Kattan, GH, Tello, SA, Giraldo M & Cadena, CD 2016, ‘Neotropical bird evolution and 100 years of the enduring ideas of Frank M. Chapman’, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 117, no. 3, pp. 407-13.

Martínez, J 2005, El ecologismo de los pobres: conflictos ambientales y lenguajes de valoración, Icaria, Barcelona.

Pálsson, G & Descola, P (eds) 2001, Naturaleza y sociedad: perspectivas antropológicas, Siglo Veintiuno Editores, México.

Pascual, U, Balvanera, P, Díaz, S, Pataki, G, Roth, E, Stenseke, M, … Yagi, N 2017, ‘Valuing nature’s contributions to people: the IPBES approach’, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 26–27, pp. 7–16.

Quintero-Ángel, M 2015, ‘Aproximación a la racionalidad ambiental del extractivismo en una comunidad afrodescendiente del Pacífico colombiano’, Revista Luna Azul, vol. 40, pp. 154-69.

Singh, SJ, Ringhofer, L, Haas, W, Krausmann, F & Fischer, M 2010, ‘Local studies manual: A researcher’s guide for investigating the social metabolism of local rural systems’, Social Ecology Working Paper 120, Institute of Social Ecology, Klagenfurt University, Vienna.

Toledo, VM, Alarcón, P & Barón, L 2009, ‘Revisualizar lo rural desde una perspectiva multidisciplinaria’, Polis, Revista de la Universidad Bolivariana, vol. 8, pp. 328-45.

UNU-IAS, Bioversity International, IGES & UNDP 2014, Toolkit for the Indicators of Resilience in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS).