Framing cultural ecosystem services in the Andes: Utawallu as sentinels of values for biocultural heritage conservation

13.12.2019

SUBMITTING ORGANISATION

Neotropical Montology Collaboratory, Geography Department, University of Georgia

Ethnostek, Calles Atahualpa y Obrajes, esquina, Comunidad de Peguche

DATE OF SUBMISSION

18/3/2019

REGION

Americas

COUNTRY

Ecuador

KEYWORDS

Reification, syncretic landscape, Imbakucha, Otavalo, Andes; Ecuador

AUTHOR(S)

Fausto O. Sarmiento1 and César Cotacachi2

1 Neotropical Montology Collaboratory, Geography Department, University of Georgia, USA.

2 Ethnostek, Calles Atahualpa y Obrajes, esquina, Comunidad de Peguche, Otavalo, Ecuador.

Corresponding author: Fausto Sarmiento

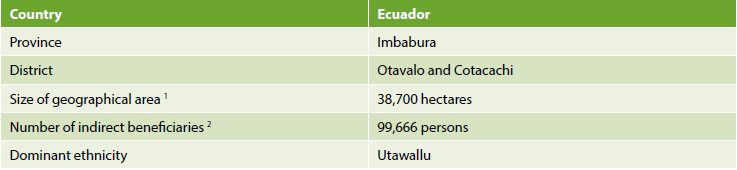

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Abstract

We describe the qualities of a cultural landscape kept within modernity by the local people of the Utawallu valley in Imbabura province of Northern Ecuador. Conservation efforts to incorporate cultural diversity alongside the biological diversity of the significant protected area in Western Ecuador are needed in order to improve protection of the traditional ancestral farmscape of the Imbakucha Basin. The different characteristics of the socio-ecological production landscape present in the site should lead to a successful initiation of a new wave of conservation in which Andean cultures are prioritized and cultural ecosystem services (re)valued.

A plea is presented to invigorate the conservation of sacred sites as a necessary step towards the Imbakucha watershed being declared the first candidate in a list of several prospective category V sites in Ecuador. UNESCO has recognized the area as a sacred site and there is a move from within the community to enlist it as a GeoPark, due to the impressive geological and morphological features of the watershed and the waves of tourists seeking adventure tourism, and not only recreation, but also ethnotourism from the indigenous market place. We grapple with the dilemma of conservation and sustainable development within a syncretic mountainscape where European practices and indigenous traditions have melded, producing a uniquely Ecuadorian trademark attraction signalling a syncretic mountainscape. We confronted the dilemma of conservation and development with the question: How can we measure the cultural value of the services provided by the Imbakucha mountainscape, and how would the perception of climate change make ethnotourism practices enhance nature conservation from an indigenous perspective?

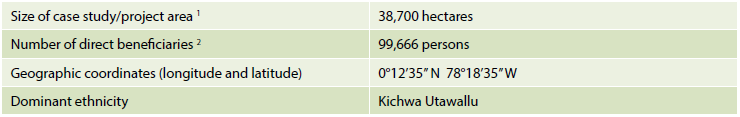

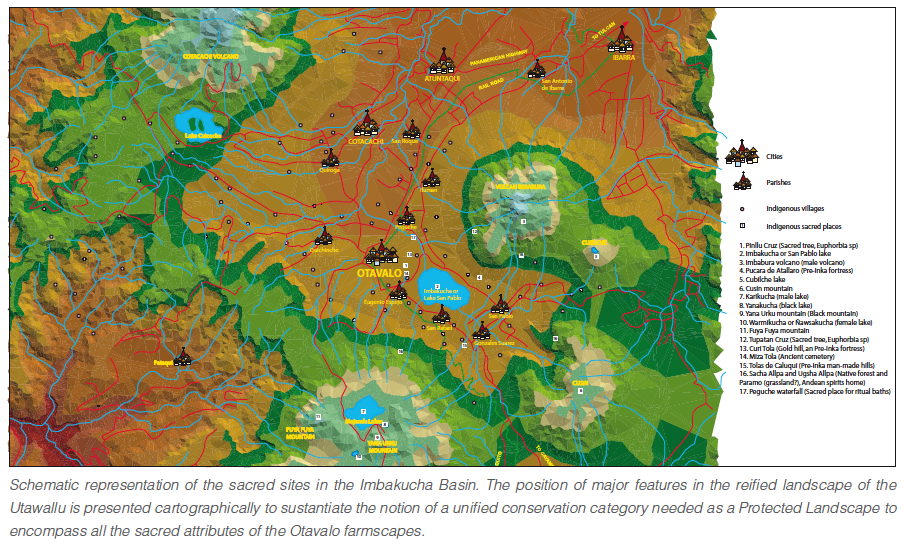

We developed ethnographic research around the most important sacred sites identified by the community members and made a photographic survey of the biocultural elements that are part of the heritage of the Utawallu runakuna. For the first time, a map of the historic sites of religious significance was produced and an inventory of the major biodiversity components was prepared. Along with forest-páramo dynamics, we identified boundary layers for cultural ecosystem services and rectified criteria to consider the Benefits from Nature to People offered with cultural values in this biocultural heritage area. We will use the momentum and the Satoyama publication as a means to energize the declaration of Imbakucha watershed as National Intangible Cultural Heritage and specific areas as sacred biocultural heritage sites.

NOTE: Kichwa is the phonetic writing of ‘Quechua’ (in Peru) or ‘Quichua’ (in Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina), which is the trade language (runa shimipi) of the Andean people. We avoid hegemony of Spanishized words, as we support the recovery of local identity and the invigoration of vernacular culture, including the use of the non-written language of the Inka. In this text, we use italics to highlight the phonetic Kichwa alphabet, while Spanish terms appear inside single quotation marks for emphasis.

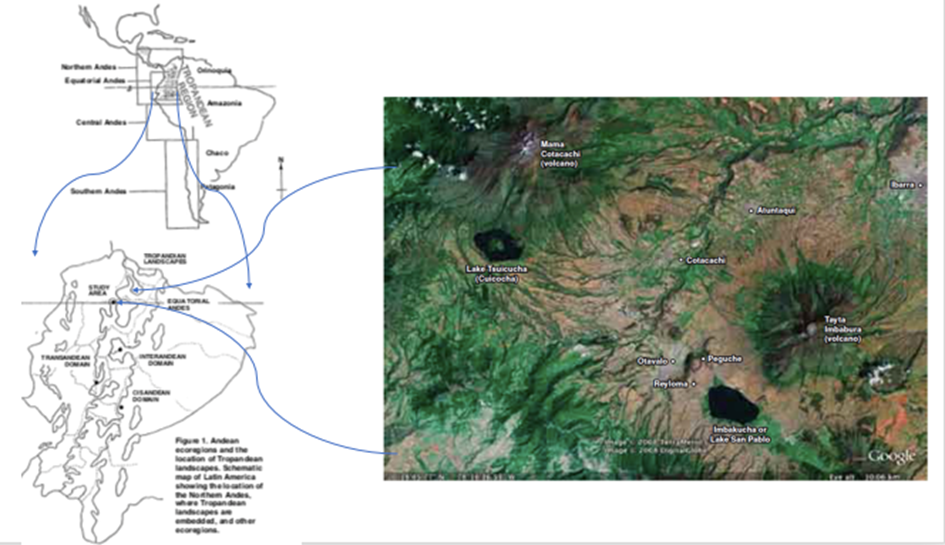

Figure 1. Map of the country and case study region

Figure 2. Land cover map of case study site. A map of the Imbakucha watershed’s main sacred sites and features, contained between the telluric guardians of Tayta Imbabura and mama Kutakachi volcanoes, with Imbakucha lake at the center of this epic mountainscape. Adapted from Google Earth and Cotacahi 2002).

1. Introduction

The Utawallu are the most visible indigenous nation of Ecuador (see Fig. 1). Known worldwide by the Spanish name of Otavalo, their fame in handcrafts, textile making, traditional medicine, music, sculpture, culinary and other forms of artistic representations have made them the most successful entrepreneurial indigenous nationality during the last decades, not only in Ecuador, but also in the whole of South America (Borsdorf & Stadel 2016). The Otavalo market, for example, draws thousands of tourists each year to the area, having become the largest indigenous market on the continent. Within this vibrant influence of local culture and the pressure of globalization, nature conservation has been challenged by the need for production of staple foods as well as other labour options, and policies have favoured wilderness preservation instead of cultural landscape values (Sarmiento 2015). Curiously, the Otavalo have no translation for “wilderness”, and their cosmological vision includes a nature-culture hybrid of respect and reciprocity, typical of Andean communities and a conundrum for mountain research literature (Resler & Sarmiento 2016). However, in Ecuador, the commodification of nature has allowed for ecosystem services to become the new guiding principle of new payment for environmental services (PES) policies; yet, emphasis goes to provisioning, and regulating functions. We argue that cultural ecosystem services (CES) are often less served by current conservation and development strategies, despite the fact that in many facets, Utawallu are cultural icons of local and indigenous knowledge. Not only the garb they proudly exhibit, but also the deeply ethical connection with Mother Earth, or Pachamama, and the establishment of sacred natural sites such as waterfalls, lakes, trees, caves, rocks, and others, have made them the stalwarts of biocultural heritage (Oviedo, Jeanrenaud & Otegui 2005). In some cases, bringing back ancient practices, in other cases developing fusion alternatives within the prevailing Western culture, ‘Otavaleños’ are being empowered by environmental leadership and indigenous revival momentum. In a dynamic socio-ecological production landscape (SEPL) that seeks to maintain biocultural heritage as way to conserve biodiversity, Otavalo is leading in offering ethnotourism and ethnomedicinal services of cultural value (Sarmiento 2016a). Cultural benefits from the Imbakucha watershed have imprinted the Otavalo people with intangibles that define their identity markers, traditions and rites, sacred sites, food and music that strengthen the Andean identity of the community, making those cultural values a very important factor in conservation planning and sustainability (see Fig. 2).

1.1 Utawallu

biocultural framework

On the equator in the northern Andes (hereafter referred to as the Equatorial Andes or Tropandean landscapes) of South America, lives a unique nation of people strongly linked to ancestral ways, but fervently immersed in the contemporary market economy. This original people or ‘pueblo originario’ identifies its ethnicity with a shared history of resistance, similar environmental quality, and an indigenous communitarian livelihood that is characteristic of Andean cultures after the Inka Empire (Seligman & Fine-Dare 2019). Populating the inter-Andean valley just north of the equator, some 50 thousand Kichwa Utawallu (known in Spanish as ‘Otavalo’) make their living in the syncretic reality between tradition and modernity in the Ecuadorian highlands (Sarmiento 2012). Despite a lack of confirmed data from population censuses in rural areas, it is thought that these people represent almost one third of the inhabitants of Imbabura province, with a growth trend of ca. 4% in the last census period. About 70% reside in rural areas around the town of Otavalo with a young populace, with 48% of inhabitants under 20 years of age (INEC 2011).

Likewise occurring to many original peoples worldwide, the ‘Otavaleño’ identity has been threatened in recent decades by 1) increasing Western influences challenging indigenous values; 2) global marketing trends weakening their ancestral customs; and 3) the destruction of unique landscape features linked to traditional livelihoods (Whitten 2003). We should be aware of these people’s ethnicity amidst the hierarchies of modernity (Appadurai 1988, Knapp 2018) and in light of the ever-growing homogenization of material monetary values and market-oriented societies (De la Torre 2006). The Kichwa Utawallu have received more attention from linguists and anthropologists at the national (e.g. Instituto Otavaleño de Antropología) and the international level (e.g. UNESCO, FAO and UNDP) than any other ethnic group in Ecuador, because they are regarded as an exemplar of the “image” of indigenous groups from the Equatorial Andes that can be exhibited to the world. Foreign assistance and governmental plans for boosting tourism in Imbabura province have catapulted the Utawallu to the forefront of entrepreneurship, and they have become known as the ‘weavers of South America’. The Utawallu, thus, accept the consequences of the westernized models that have had such negative effects on the environment in the Imbakucha Basin, with the iconic ‘San Pablo’ lake (Imbakucha). This lake and its surrounding bucolic landscape have been known since antiquity as the ‘Valley of Dawn’ and are the birthplace of the last Sapa Inka emperor, Utawallpa (sometimes known as Atawalipa or ‘Atahualpa’); today, nonetheless, this site strives to maintain its identity amidst increasing modernization (MAE 2012).

Modernity in Imbakucha must recognize the essence of place shared by groups of similar ethnic backgrounds that remain hidden behind political boundaries and accesses (Whitten 2003); this is the case of the Utawallu (in the northwestern zone), the Kayampi (southeastern zone), the Kutakachi (western zone by Lake Tsuikucha or ‘Cuicocha’) and the surrounding villages near Otavalo, such as the Imbala, Atuntaki, Illumani and Karanki (Rosales 2003). It is because of this rich mixture of cultures, still holding onto their traditional livelihoods, that efforts to turn the ‘Valley of Dawn’ into the ‘Switzerland of Ecuador’ have succeeded and led to a boom in ethnotourism, agritourism and ecotourism in the Imbabura province. A mere 110 km north of Quito, the capital of Ecuador, connected by the reshaped and improved Pan-American Highway, visitors are surprised to find lakes, mountains, farmlands, and small Andean villages, interspersed within a matrix of different shades of green. Weekend tourism is very high, with some 50,000 potential buyers flocking to the Saturday market—considered as the largest outdoor market in South America—and actually doubling the town’s population in a matter of hours (see Fig. 3). Here, the 90 concrete parasols designed in 1973 by female Dutch architect Tonny Zwollo are converted into a colorful showcase of punchu (‘poncho’) and other handicrafts. This open area—or ‘Ponchos’ Plaza’—is considered by many travelers as ‘the mother of all markets’, since the colorful market stalls have spilled over into the streets of the central district of the city of Otavalo; however, not only monetary transactions occur here, but also seed swaps, animal/goods exchanges and bartering are also frequent (Meisch 2002). The area of Otavalo, including lake Imbakucha, receives many tourists from all over the world. Nevertheless, the Otavalo market is not the only tourist attraction in the area: many young people, who make up 26.7% of the total visitors by age (MINTUR 2018), use ethnotourism operators to get to know ethnic group perspectives regarding conservation and development scenarios, along with the opportunities of adventure tourism or ecotourism that require a rather active lifestyle.

Figure 3. The Otavalo Market side streets show the vibrancy of the exchanges, including bartering, of many different type of goods and services, including manufactured items but also swapping seeds, animals and farm products (Photo: Cesar Cotacachi).

Many elders, including Mario Conejo, the original mayor of Otavalo, emphasize that the trading and traditional tourism practices of this market have been the foundation of their local identity since antiquity. The Utawallu have always produced and sold valuable handicrafts throughout the Andes through relocated, sedentary or expatriated members of the Kichwa Kayampi (mitima) ethnic group and traveling entrepreneur merchants of the Kichwa Utawallu (mindala) ethnic group. Even today, it is not uncommon to find ‘Otavaleños’ traveling to faraway countries, becoming today one of the most recognizable original people on the global scene, with established stores in New York, Tokyo and London and street-vending in plazas from Amsterdam to Zagreb. Often mixing their selling of art and crafts with Andean musical performances in streets and squares, the ‘Otavaleño’ traveling merchants of today are ambassadors for Andean culture abroad, and the reason why tourists come to this corner of the world.

1.2 Biocultural heritage and the spiritual dimension

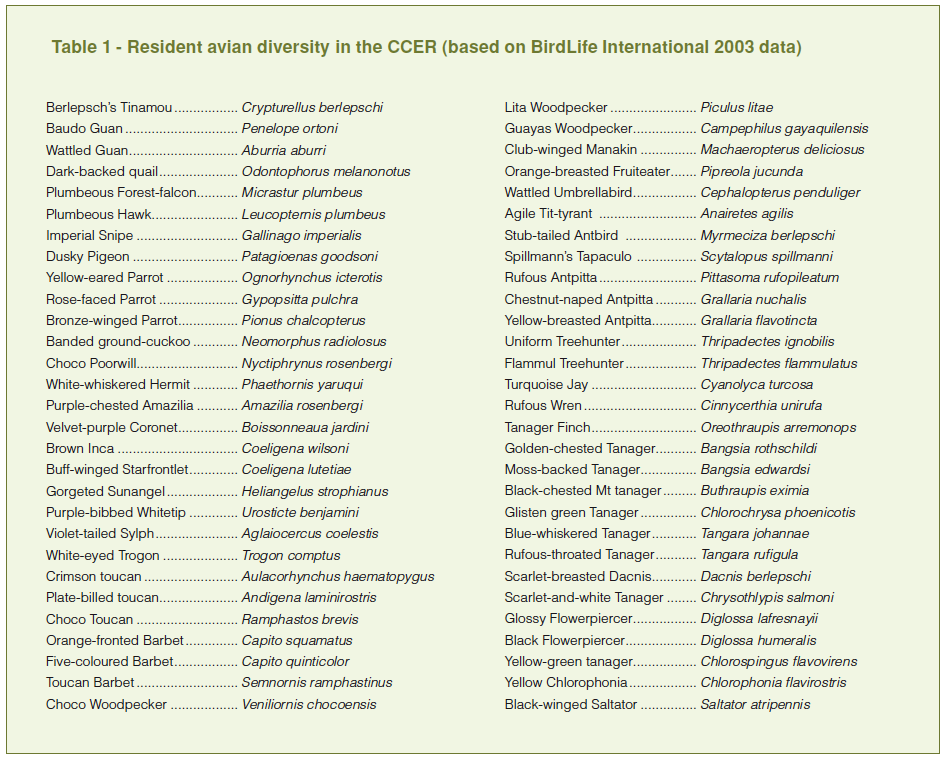

Instilled in their lifestyle and spirituality, the Utawallu have close links with the natural environment: work on the land, respect for their sacred sites, and spirituality shared by the members of the communities that live in the valley, are important components of their lives (Cotacachi 2002) (see Figure 4) . There is a plethora of bird species to watch on private reserves in the basin, such as the Hacienda Cusín, listed within the Important Bird Diversity areas, with spots for birdwatching enthusiasts with record numbers of hummingbirds and many passerines. As an example, Table 1 shows a list prepared by BirdLife International for the surrounding areas. There are also small in-situ conservation initiatives, such as a condor (Vultur gryphues) rewilding camp, several hatcheries with local fish species and nurseries for Camelidae, particularly llamas (Lama glama). Locals are often referring to the mystical Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus) or ukumari, as a frequent visitor to the borders of cloud forest areas and cultivation fronts, particularly of maize, their favorite pillaged food. The flagship cougar (Puma concolor) has been registered within the Imbabura slopes and also on the western flank of the Kutakachi volcano, where the entire biota explodes with the influence of the Chocoan biodiversity hotspot.

Figure 4. Ritual procession to reaffirm the Utawallu identity around the pukara of Reyloma, in route to the pinllucruz. Maintaining the identity markers and reifying the presence of sacred natural sites, such as the tree, the lake and the waterfall nearby, helps in cohesive practices of socioecological wellbeing. (Photo: César Cotacachi).

Table 1. A checklist of bird species found in the surrounding area of the Imbakucha watershed and the nearby western Andean flank of the Imbabura province. Adapted from Birdlife International 2018.

The Utawallu not only analyze the practices employed for conserving natural resources, but also incorporate environmental conservation and protection into their lives, since environmental and religious practices are seen to be indistinguishable. Conservation practices in this area are maintained through the observance of ancestral whispers (sensu Berkes 2012) that reveal the ecological soul, spiritual sympathy, and energy emanating from the Imbakucha Basin, all of which provide a basis for their cosmological worldview. This also explains the following that traditional medicine has and the number of yacha, shamans or medicine men and women, concentrated in the town of Iluman, who have been recognized by the government and certified as alternative medicine providers. Furthermore, adults work the land every day, tending gardens, livestock, and farms and passing concerns and care for the environment on to their children, along with the notion of respect for natural resources and reverence for the sacred natural sites (eds. Sarmiento & Hitchner 2017) that make them uniquely Utawallu (see Fig. 4). This education, transferred from one generation to another well into adolescence, is an important intergenerational legacy of these original people and a way of conserving the Imbakucha Basin. The majority of ‘Otavaleños’ (Utawallukuna) and ‘Cotacacheños’ (Kutakachikuna) are either Roman Catholics or Evangelical Christians due to the colonization of the area in the early 1500s by the Kingdom of Castile, the subsequent colonial alignment with Spain and the Vatican, and the presence in recent years of quite active missionaries from the United States of other Christian denominations. Nevertheless, religious affiliation has generally remained separate from spirituality in the local people. This important feature of Andean culture has been described as syncretism and allows both Western and original beliefs to coexist in the area (Rodríguez 1999; Sarmiento, Rodríguez & Argumedo 2005), providing a trope of ecocritical narratives in what are now known as syncretic landscapes (Sarmiento 2017), a reflection of the dynamic fusion of Western and native practices of this SEPL functioning within the tenets of the Satoyama Initiative (see Fig. 5).

These fusion landscapes abound in the tropical Andes, where a mixture of exotic species (e.g. Australian blue gum tree –Eucalyptus globulus, Monterrey pine –Pinus radiata, African kikuyu grass –Pennisetum clandestinum, Fenix palm –Phoenix dactylifera) with native species (e.g. Black walnut –Juglans neotropica, Hand of Puma –Oreopanax argentata, –Mountain cedar –Cedrella montana) or Andean wax palm –Ceroxylum andicola) form the forested matrix of the manufactured mountainscape. Here, the physical presence is luxuriant with greenery and fertility all year round, making the phenosystem a delightful deduced panorama. Amidst these patches or plantations, mostly prevalent in the homogenized landscapes of the countryside worldwide, there are several home gardens that still retain elements of native flora and fauna that are mostly used for medicinal or culinary purposes. Working like the milpa described in this volume for Mesoamerica, the chakra of the Utawallu is for the tropical Andes the treasure trove of agrobiodiversity. The chakra gardens include corn –Zea maiz; beans –Phaseolus vulgaris; squash –Cucurbita ficifolia; quinoa –Chenopodium quinoa; potato –Solanum tuberosum; ‘guaba’–Inga edulis; ‘tomate de árbol’ –Cyphomandra betacea: ‘taxo’ –Passiflora tripartite, ‘aguacate’ –Persea americana; ‘granadilla’ –Passiflora ligularis; ‘naranjilla’ –Solanum quitoense; mountain papaya –Vasconcellea heilbornii; and many other species of great cultural significance, not only for medicine or food, but also for mystical association with the surrounding mountains, such as the ‘lechero’ –Euphorbia laurifolia described below. This unseen dimension of the cryptosystem allows the integration of inductive qualitative factors such as magic, rite, spirituality and myth. Therefore, the biocultural heritage approach also provides landscape heterogeneity accentuating the diversity of species with the various local cultural values.

Figure 5. A group of people in Otavalo’s central park, exhibiting the traditional garb and other attributes associated uniquely with this group, ready to celebrate kuya raymi to thank Pachamama for her willingness to receive seeds for the new harvest (Photo: Cesar Cotacachi).

The Utawallu, for whom ‘place’ is not merely a collection of spatial features, but a spiritually, holistic home base (Carter 2008), understand many intangible values of the cultural landscape. Their esteem for water is derived from their own spirituality and the significance of sacred wetland sites in the many ancient rituals they perpetuate. The importance of this sacred dimension is derived from the runa taytiku ancestors, Utawallu grandparents, and parents, and is passed with intergenerational sharing to the very young (wawa) and teenagers (wambra) through oral history; it includes the essential rituals of initiation and purification associated with the heightened spirituality observed at sacred sites (Sarmiento, Rodríguez & Argumedo 2005). Indeed, sacred loci connected to spirituality in Imbakucha are mostly found in locations where water emanates: they may be where succulent plants or a sacred tree (e.g. pinllu or pinkul, or ‘lechero’ tree, Euphorbia laurifolia) grow or where water bodies such as streams (wayku), rivers (yacu), coves (pukyu), waterfalls (phakcha), lakes (kucha), ice (rasu) or snow (kasay) are found, or anywhere in which a form of water can exist with its purifying essence. The very presence of imposing volcanoes and life-giving lakes creates a well-respected observance of cycles of plant production and a concentration of fauna and flora in certain areas of their Andean lifescape.

1.3 A note on methodology

This work is an ethnoecological study that builds upon extensive understanding of Andean ecology and anthropological nuances of the region (Knapp 1991). This multimethod approach required intensive and extensive fieldwork and ethnographic tools. The initial study was undertaken for a Master’s thesis at a local university to identify the sacred dimension of the valley and its main characters. It included more than two years of groundwork, interviews and surveys that were conducted in the different communities of the watershed. It was followed by a comparative study with more statistical and geospatial considerations for an Honor’s thesis at a land-grant university in the US, with more works included in an updated literature review and incorporating critical discourse analysis, focus group workshops, expert interviews and observational studies that brought in the current tropes of the biocultural heritage narrative. Individual studies are published elsewhere (Cotacachi 2002; Sarmiento 2003, 2012; Sarmiento, Rodríguez & Argumedo 2005; Carter 2008; Sarmiento, Cotacachi & Carter 2008; Carter & Sarmiento 2011; Sarmiento & Viteri 2015) and bring the multimethod approach summarized hereby.

1.4 The Study Area

The Imbakucha Basin contains the largest Andean lake in Ecuador and is located in the province of Imbabura in northern Ecuador. Here, the Kichwa ethnicity is the more prevalent of the two Utawallu groups, which are separated by the administrative county boundaries: The Kayampi to the southeastern reaches of the lake towards the ‘Cayambe’ volcano, and the Utawallu, referred to as ‘Cotacacheños’ (Kutakachikuna), living westward and the ‘Otavaleños’ (Utawallukuna) living northward of the lake. Further differentiation is also possible within the Kichwa ethnic groups, which creates a spectrum of ethnographic and epistemological oddities that makes Ecuador such a rich, pluricultural, multilingual nation (Moya 2000, Whitten 2003). A good example is found where the ‘Otavaleños’ live in the Imbakucha Basin: the Kutakachikuna dwell near Mother ‘Cotacachi’ volcano by the city of Cotacachi, while the Utawallukuna dwell near Father Imbabura volcano by the city of Otavalo (see Fig. 6). Both cities are within 48 km of each other and share many environmental traits and similar administrative histories (Keating 2007). For many conservationists, the two areas are located within the same type of ecosystem. Otavalo’s sacred sites include Taita Imbabura (the Imbabura volcano or Yaya Imbabura; Imbakucha proper or the Lake ‘San Pablo’, the ‘Lechero’ Tree on the pukara of ‘Reyloma’, and the waterfall in ‘Peguche’ parish, also known as Phakchayacu. Cotacachi’s sacred sites include Mama Cotacachi (Kutakachi Volcano), the Cotacachi-Cayapas Ecological Reserve and Tsuykucha crater lake in the shadow of the volcano.

Figure 6. Google Maps view of the location of the study area in relation to the country of Ecuador in South America. The sacred mountains (Imbabura and Cotacachi) frame the valley where Imbakucha Lake is located.

Given that the views of the original people are important in this heavily indigenous-populated area, the ideas of the Kutakachikuna are held in high esteem by the local government, ensuring public support for the sanctity of these concepts. Thus, conservation will continue to be provided, whether or not the national government includes them as part of its mandate for the conservation of protected areas (for instance, see Ramakrishnan 2008), including the recent designation of the area as a Global GeoPark, officially declared by UNESCO in February 2019. Presumably, ecotourism helps the local economy in such a way that Imbabura residents will continue to preserve their sacred sites for as long as they have a degree of privacy that allows them to respect their ancestors according to their spiritual traditions; this will create the type of de facto conservation that currently occurs around the sacred sites of the world (eds. Verschuuren et al. 2010) in general, and of the Imbakucha Basin in particular (Sarmiento, Cotacachi & Carter 2008).

2. Cultural Ecosystem Services Revisited

Ecosystem Services have experienced enormous traction in both academic and field practitioners over the last two decades, with more publications appearing each year on the topic. However, studies on Cultural Ecosystem Services (CES) have been less explored due to limited access to gather intangible values, which demands lots of time and resources spent on the ground via ethnographic research. In addition to the lacking number of CES studies, previous works have been focused on urban areas, leaving out mountain SEPLs, which hold significant CES values shared communally. In exurban areas or rural areas in which people live closer to nature in the farmscape, they have developed significant cultural ties with the mountainscape, including the spiritual dimension. Hence, communities with nearby mountains hold unique and locally inherited values, more so than aesthetic or recreational values alone (Kong & Sarmiento, in press).

However, mountain landscapes near Utawallu communities are under constant threat of land alteration or development pressures tending toward farmscape transformation. Also, numerous communities themselves experience rapid socioecological changes, including the segmentation of religious affiliation and the increase of new evangelical or Christian denominations, instead of the traditional Roman Catholic affiliation, which may result in loss of traditional and syncretic value systems shared in this collective. One of the earliest stages in successful landscape conservation is to identify the values shared in the landscape. Identifying CES, therefore, supports optimizing resource management by acknowledging major features, activities, and qualities comprising the soul of the Utawallu mountainscape. Also, exploring various values shared communally helps to reinforce identity, which can lead to creating solid place attachment and local solidarity. This was one of the specific emphases given by one of us (César Cotacachi) as the first indigenous leader in heading the political office of Otavalo in history, reporting directly to the President of Ecuador on issues related to Otavalo city and county. Despite ardent conservation work, the pressures of industries and other productive interests, such as agribusiness, mining, and manufacturing, are strong enough to produce a rift between the cultural assets of the indigenous community versus the needs of development conceived within the economy of the global market.

2.1 Reifying the Imbakucha watershed

Otavalo and Cotacachi are northern Ecuadorian counties where original peoples or ‘pueblos originarios’ maintain a close spiritual link with the environment (or kawsay sapi) through several factors that are instilled within their lifestyles and spirituality (Cotacachi 2002). A main component includes their work with the land and the sacred sites that are interconnected with their spirituality (or runa rimay). They do not analyze the practices that are put into conserving environmental resources (or puchuchina) as separate issues; instead, according to many indigenous citizens, conserving and protecting the environment is incorporated into their lives, as environmental and religious practices (or wakaychina) are known to be indistinguishable.

According to many Kichwa Utawallu, the conservation practices in this area are maintained through the observance and understanding of the “ancestral murmur” (or Aya) that shows the soul ecology, spiritual synchrony or emanating energy found in the Imbakucha basin for conservation practices in their communities (or llakta kawsay); also, the work of ecologists in this region, the government’s Ministry of the Environment, indigenous-led parochial and city governance, and the few non-profit agencies in the area are devoted to environmental conservation. Furthermore, the adult indigenous citizens work with the land on a daily basis, tending to their gardens, livestock, and farms. These adults pass their attention to and care for the environment as traditional ecological knowledge, TEK, (or runa yachay), along with the notion of the importance of keeping reverence to natural resources therein, to their children. This education conforming to the Andean identity trilemma (i.e., Andeanity, Andeaness and Andeanitude) observed with enthusiasm (Yanatin) amid a duality of choice (Masantin) that is being passed from their ancestors to the younger generations (or shina nin) is the important legacy and intergenerational equity of the original people for conserving CES as identity markers of the indigenous territory.

2.1.1 Institutional framework and local governance

The administrative structure of the Imbabura province includes six counties (Ibarra, Antonio Ante, Cotacachi, Otavalo, Pimampiro and Urcuquí) all of them managed by the Imbabura Provincial Council. According to the new Ecuadorian constitution that tends to decentralize governmental functions to the local level, several Autonomous Decentralized Governmental (GAD) units operate in the area; in particular, the GAD Otavalo, the GAD Cotacachi and the GAD San Pablo are the key players in the planning and execution of development initiatives in the Imbakucha watershed. The mayors of Otavalo and Cotacachi have recently given priority to community-driven initiatives and favor ecotourism development and cultural revitalization. The overall progress noticed in vital infrastructure and common areas, such as sport complexes, schools, open-air markets and gardens and boulevards, has captured the attention of urban planners for having model towns accepting modernity but imbued with local culture. There are provincial leaders dealing with tourism, forestry, agriculture and culture; however, a sectorial separation seems to pervade the bureaucratic functions of state offices. There are several civil society groups that confirm the cultural oddities of the region, particularly those that join the professional ancestral healers (yachas), small producers, artisans and gremial organizations. There are several youth organizations as well as student groups that tend to work with community extension work and environmental education campaigns, and cultural rejuvenation, particularly in music and dance. Private foundations and other NGOs operate to conserve specific areas, such as Lita, Pimampiro, Mariano Acosta and Intag, most of them engaged in fighting deforestation, mining, fishing and illegal traffic of endangered species in the vicinity of small private reserves or bordering larger protected areas of the Andean flank.

2.1.2 Sacred natural sites conservation

While the majority of ‘Otavaleños’ and ‘Cotacacheños’ are Christian (either Catholics or Evangelicals), their religion does not conflict with the spirituality found in their cosmovision (or runa yachay). This important feature of the Andean culture has been described as syncretism that has helped both Western and original beliefs coexist in the area from colonial times to the present (Rodríguez 1999; Sarmiento 2017). However, fundamentalists have pointed out important anachronisms that cannot admit the sacredness of a tree, or a waterfall (Vasquez-Fuller 1995). In the synchronic approach, this non-formal education, in addition to the Utawallu’s environmental non-profit work with reforestation and education, allow the mountain communities to lead more environmentally-friendly lives while benefiting from the conservation of the two extensive protected areas on the outer Andean flanks, two of the largest ecological reserves of the country (Cotacahi-Cayapas towards de Pacific coast and Cayambe-Coca towards the Amazonian lowlands), and the clean water from these reserves, taken as more than mere spatial features, but spiritual ones. Therefore, the indigenous nation occupies the Imbakucha watershed flanked by the two tutelary mountains framing their conceptual sacred landscape (see Fig. 2).

These original people have great respect for the environment; therefore, they also have reverence for its natural resources, specifically water, which is one of the most important energies of the mountainscape (urku ayacuna). Their esteem for water is derived from their cleanness, spirituality and the significance of sacred sites in the indigenous culture. This observance of sacred sites comes from the conversations of indigenous peoples’ ancestors, grandparents, and parents (tinkuy rimay), and the essential rituals of initiation and purification (wuatuna samay) associated with their spirituality and the sacred sites. This also explains the mythology associated with plants (e.g. tutura reed), animals (e.g. ukumari bear) or watery phenomena (e.g. rainbow for ‘mal del arco’ maladies, or seepage walls for ‘rinconada’ frights, or surface lake eddies for ‘duende’ sights).

2.1.3 Sacred water bodies

Sarmiento (2003) argued that sacred sites must integrate conservation scenarios for biocultural heritage preservation, since this will in turn protect water resources that are located in the same areas as sacred sites (Barrow & Pathak 2005), particularly when you have montane tropical cloud forest full of epiphytic gardens, often shrouded in horizontal precipitation. Although notwithstanding their spirituality, while many original peoples respect sacred sites, there are many who do not (Rhoades & Zapata 2006). In the event of the recognition of an officially declared conservation category, the sacred sites of the Utawallu will be protected for posterity, in the same way that its rich agro-biodiversity will be safeguarded. One way to ensure that sacred sites are protected is to place them under the protection of Category V of IUCN with detailed guidelines, as edited by Robert Wild and Toby McLead (2008). These guidelines are aimed at “improving the management of sacred natural sites in formally designated protected areas, as well as supporting those that lie outside protected area boundaries” (eds. Wild & McLead 2008). Recent investigations into the retreat of the Mama Kotakachi glacier provide evidence of local ethno-ecological knowledge on the global climate (Rhoades, Zapata & Aragundy 2008) and changes associated with the transformation of original lifescapes. As documented by Nazarea and Guitarra (2004), the anthropomorphic idea of the mountain landscape offers conviction to the Utawallu that they are connected to the land through sacred sites, where water rituals are still performed and observed as nation-building traditions among their people. The collection of rock glacier and/or glacier ice as ceremonial “payments” or ‘pagamentos’ to the Pachamama, is one example. Another example, the yearly initiation shower in the sacred ‘cascada de Peguche’. The Piguchi waterfall (or Phakchayacu) is located in a small private reserve and serves as the main purification site for the Kichwa Utawallu during the Festival of the Sun (Inti Raymi), a weeklong celebration held during the summer solstice.

The ‘Lechero’ or yayitu or taitiku (little grandfather) is an emblematic tree (pinllu or pinkul) or ‘árbol sagrado’ tree (Euphorbia laurifolia) growing on top of pukara or ‘Reyloma’ that overlooks the watershed, as an embodiment of the fertility of Imbakucha lake, being a majestic landmark in their local communal lifestyle; the tree of eternal life is a medicine tree that symbolizes life and death (Wibbelsman 2005a). Located on top of ‘Reyloma’ hill, the ‘Lechero’ represents “mutual dependency” between the original people and their environment (Wibbelsman 2005a). Clones of the ‘Lechero’ tree are found in most households because it is highly respected and sacred; also, it has practical importance in ethno-medicine and good potential as living fences (see Fig. 7). The Utawallu believe that the tree protects their fields and homes: “the milky sap of the tree is a natural acid that burns the skin…[and is used] for warts, curing deafness, toothaches, eye problems, liver cirrhosis, nerves, bacteria, fungi, viral infections and abortions” (Wibbelsman 2005b).

Figure 7. The sacred tree of the Otavalo is maintained with ornate plantings surrounding the ancestrak location of the mature tree of pinllucruz, despite the adventurers’ sacrilege of burning camp fires, or even bone fires atop of the pukara of “Reyloma”. (Photo: Fausto Sarmiento)

Lake ‘San Pablo’ lies at 2,660 m ASL. It has a maximum depth of 35.2 m (Gunket 2000). Imbakucha, the largest tectonic lake in Ecuador, is nearly circular and is situated at the base of Tayta Imbabura; there is some shoreline development, ranging from tourist resorts and villages, to farmland (see Fig. 8) . The lake plays an important role in the Utawallu arable lands (allpa) of the community: its water is used for irrigation, for animals to drink, for collecting drinking water and for fishing, washing clothes, and the cultivation of ‘totora’ reeds to manufacture ‘aventadores’ or squared handled fans, sleeping mats, coverings and rugs, as well as to build small boats (Gunket 2000). It is also used for recreation, including boating, and tourism activities (Willis & Seward 2006). However, because of “the intensive cultivation, steep slope of the fields and high precipitation rate that results in much erosion…[as well as the] high input of nutrients into the lake”, Imbakucha is an eutrophic lacustrine system that needs remediation (Gómez Rosero 2017, 155). Furthermore, sewage from the main settlement flows through a pipe directly into the lake and into the Itampi River (i.e. the main water source for lake communities and for rural dwellings and flower greenhouses upstream and downstream) (Gunket 2000). Although development has affected Imbakucha Lake, its waters are still sacred among Kichwa Utawallu communities, as documented by Nazarea and Guitarra (2004) who reveal the relationship between the Castilian conquistadors and the original people, as well as the importance of water to the Kichwa culture (see Fig. 9). To a backdrop of two tall mountains and their spirits (urku apukuna), both ‘Cotacacheños’ and ‘Otavaleños’ refer to the Imbakucha Basin in terms of the cultivation of the area’s different environments and the use of altitudinal defined zones that include the lacustrine (wampu allpa), the piedmont (ura allpa), the steep mountain slopes (jawa allpa), the Andean forests (sacha allpa), the high grasslands or ‘pajonal’ (ugsha allpa), and the screes of periglacial assemblage (rumi allpa).

Figure 8. A panoramic view of Imbakucha lake, formerly known as Laguna de San Pablo, the largest water body in Ecuador and the home base of the Utawallu Kichwa nation, , making evident the dilemma of keeping traditional sustainable practices of subsistence agriculture amidst the maelstrom of modernity of the globalized world. (Photo: César Cotacachi).

Figure 9. Panoramic view of the location of the study area in relation to the telluric presence of dormant volcano Imbabura. The sacred mountains frame the valley where Imbakucha lake is located at the epicenter of the sacred geographies that link water (yaku), cloud (puyu), mountain (urku) and people (runa) in a complex, yet harmonious and proud existence. ( Photo: César Cotacachi).

The Utawallu associate their spirituality with the holistic lifescape (Carter & Sarmiento 2011) with more meaning than the simple tangible surroundings, possessing a deep understanding of the intangible values of the cultural landscape. The Kichwa Utawallu, therefore, observe Andean mythology by reverence to the environmental blessings (not services) of the valley, above all water, which is one of the most important reifications of their mountainscape. The importance of this sacred dimension is derived from Utawallu ancestors and is passed-down through oral history; it includes the essential rituals of initiation and purification associated with the heightened spirituality observed at sacred sites (Sarmiento, Rodríguez & Argumedo 2005), mainly around the ‘rinconadas’ or mountain seepage sites, the actual lakeshore or mythical ‘recodos de laguna’ and the Piguchi waterfall, where cleansing and initiation rituals are still held. Indeed, sacred loci connected to spirituality in Imbakucha are mostly found in locations where water emanates: they may be where useful reeds (tutura) were planted, or where water bodies such as streams (wayku), rivers (yacu), seepage coves (pukyu), waterfalls (phakcha, churru), lakes (kucha), ice (rasu) or snow (riti) are found, or anywhere in which a form of water can exist with its purifying essence (Sarmiento 2016b). The very presence of imposing volcanoes and life-giving lakes create a well-respected observance of cycles of plant production and a concentration of endemic fauna and flora in certain areas of the Andean lifescape, making the Imbakucha watershed sacred a comprehensive sacred park.

3. The way forward

Incorporating the sacred dimension is only one of many ways to achieve integration of CES into biocultural heritage preservation. By presenting the uniqueness of the Utawallu and their mountainscape, we seek to sensitize international audiences in helping break the trend for protecting nature only because of its utilitarian value, commoditizing the services of nature (such as providing, regulating or supporting the physical content of the landscape or phenosystem), but also for protecting the nature/culture hybrid of the present—mainly because of the contributions from nature to people (such as intangibles, social and landscape values for the psychosocial mindscape or cryptosystem), including the Andean identity.

4. Conclusion

Biodiversity is threatened, since the settled area of Imbakucha has become overgrown with introduced species, most of them weeds and fast-growing invaders such as the African grass (Kikuyo elephantopus), Monterrey pine (Pinus radiata), African bristlegrass (Setaria sphacelata) and the Australian blue gum tree (Eucalyptus globulus). Towards the outer boundaries of the Imbakucha Basin, protected areas have been established with the purpose of maintaining examples of pristine natural habitats, including the ‘páramo’ grasslands and the remnants of the Andean forests. The lack of understanding of landscape archaeology of the area and of the true ‘natural’ history of the elements of the cultural landscapes of the Kichwa Utawallu has exacerbated a divorce between the goals of preservation (i.e. nature protection) and of conservation (i.e. nature management). By continuing to consider Andean forests and ‘páramo’ grasslands as ‘natural’ ecosystems, instead of syncretic, manufactured SEPLs, conservationists and government agencies are hindering the (re)affirmation of the cultural identity of the ‘Otavaleños’; instead, they are bolstering the hegemony of a foreign concept of conservation based on consumption-linked, species-oriented conservation and a forced “pristine” conceptual framework that separates the human dimension from everything else, rather than observing the ancestral cosmological vision of the Utawallukuna, integrating the Andean trilemma (Sarmiento et al. 2017) for a comprehensive CES valuation.

More research must be conducted into sacred site conservation and its relation to spirituality, as well as into the objectification of landscape features, ecological knowledge, ecotourism, environmental education and environmental ethics (Verschuuren et al 2010). Additionally, future studies in Imbakucha should include investigations of the adaptations of Utawallu communities to the ever-changing cultural environment surrounding them. These studies should index the reification of landscape attributes, and formal protected area status should be given to the main features of the landscape with appropriate designations such as GeoPark, ‘Reserva Paisajística’, ‘Sitio Sagrado’, Spiritual Park, Protected Landscape, Religious Monument and/or a designation within the UNESCO program for Sacred Site Conservation. Ecuador will benefit greatly from including Category V conservation in its National Strategy for the Conservation of Protected Areas; the current administration has already supported that socio-ecological production landscapes will be a goal of the new Law of Culture and the works of the Institute of Cultural Heritage. The sacred sites we have discussed must be protected not only for their environmental value, but also out of respect for the significant intangibles present in the different sacred sites of the Kichwa Utawallu around the Imbakucha Basin that contribute greatly to the Ecuadorian identity in Latin America and the world (see Fig. 10).

Figure 10. As a concluding graphic remark, happy faces portrayed to convey a message of hope that new generations will follow ancestral practices of respect for Pachamama and of reciprocity and self-awareness, so that the Utawallu sacred natural sites be venerated and maintained for future generations, achieving Sumak Kawsay or the collective ‘good living’ to which all Satoyama landscapes aspire. The celebratory ambiance of the children translates the optimistic outlook for the socioecological production landscape of Imbakucha to incorporate the benefits of uncommodified values in nature conservation. (Photo: César Cotacachi).

References

Appadurai, A 1988, ‘Putting hierarchy in its place’, Cultural Anthropology, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 36-49.

Barrow, E., & Pathak, N. (2005). Conserving ‘unprotected’protected areas–communities can and do conserve landscapes of all sorts. In: Brown, J, Mitchel, N & Beresford, M (eds.), The Protected Landscape Approach: Linking Nature, Culture and Community, World Conservation Union IUCN, Gland and Cambridge.

Berkes, F 2012, Sacred ecology, Routledge, New York.

Borsdorf, A & Stadel, C 2016, The Andes: A Geographic Portrait, Springer.

Brown, J, Mitchel, N & Beresford, M (eds.) 2005, The Protected Landscape Approach: Linking Nature, Culture and Community, World Conservation Union IUCN, Gland and Cambridge.

Carter, LE 2008, ‘Assessing environmental attitudes of residents of Cotacachi and Otavalo, Ecuador to conserve sacred sites’, A.B. Thesis (Unpublished), University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia.

Carter, LE & Sarmiento, FO 2011, ‘Cotacacheños and Otavaleños: local perceptions of sacred sites for farmscape conservation in highland Ecuador’, Journal of Human Ecology, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 61-70.

Chen, Y, Parkins, JR & Sherren, K 2018, ‘Using geo-tagged Instagram posts to reveal landscape values around current and proposed hydroelectric dams and their reservoirs’, Landscape and Urban Planning, vol. 170, pp. 283-92.

Cotacachi, C 2002, ‘Etnoecología de Imbakucha’, MA Thesis (Unpublished), Catholic University of Ecuador, Ibarra.

De la Torre, C 2006, ‘Ethnic movements and citizenship in Ecuador’, Latin American Research Review, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 247-59.

Gómez Rosero, TG 2017, ‘Bioremediación de lagos tropicales eutrofizados: estudio del Lago San Pablo (Ecuador)’, Master’s thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

Gunket, G 2000, ‘Limnology of an equatorial high mountain lake in Ecuador, Lago San Pablo’, Limnologica, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 113-20.

INEC 2011, Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda, Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Censos, Quito.

Keating, PL 2007, ‘Fire ecology and conservation in the high tropical Andes: observations from Northern Ecuador’, Journal of Latin American Geography, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 43-62.

Knapp, G 1991, Andean Ecology: Adaptive dynamics in Ecuador, Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado.

Knapp, G 2018, ‘Strategically relevant Andean environments’, in The Andean World, eds L Seligman & KS Fine-Dare, Routledge, New York, pp. 17-28.

Kong, I & Sarmiento, F (in press), ‘Using social media to identify cultural ecosystem services in El Cajas National Park, Ecuador’, Mountain Research and Development.

Mallarach, J-M and Papayannis, T (eds.) 2007, Protected Areas and Spirituality, Proceedings of the First Workshop of The Delos Initiative, Monteserrat, Publicaciones de l’Abadia de Montserrat, IUCN and Montserrat, Spain, Gland, Switzerland.

MAE 2012, Mega-País. Ministerio del Ambiente de Ecuador, Imprenta Mariscal, Quito.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005, Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis, Island Press, Washington, DC.

Meisch, LA 2002, Andean entrepreneurs: Otavalo merchants and musicians in the global arena, University of Texas Press, Austin.

MINTUR 2018, Estadísticas turísticas del Ecuador, Ministerio de Turismo, Ecuador.

Nazarea, V & Guitarra, R 2004, Stories of Creation and Resistance, Ediciones Abya-Yala, Quito.

Oviedo, G, Jeanrenaud, S & Otegui, M 2005, Protecting Sacred Natural Sites of Indigenous and Traditional Peoples: an IUCN Perspective, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Ramakrishnan, PS 2001, ‘Ecological threads in the sacred fabric’, India International Centre Quarterly, vol. 27, pp. 109-22.

Resler, L & Sarmiento, FO 2016, ‘Mountain Geographies’, in Oxford Bibliographies in Geography, ed. B Warf, Oxford University Press, New York.

Rhoades, R & Zapata, X 2006, ‘Future visioning for the Cotacachi Andes: scientific models and local perspectives on land use change’, in Development with Identity: Community, Culture and Sustainability in the Andes, ed. RE Rhoades, CABI Publishing, United Kingdom, pp. 298-306.

Rhoades, R, Zapata, X & Aragundy, J 2008, ‘Mama Cotacachi: history, local perceptions, and social impacts of climate change and glacier retreat in the Ecuadorian Andes’, in Darkening Peaks: glacier retreat, science and society, eds. B Orlove, E Wiegandt & BH Luckman, University of California Press, Berkeley, pp. 216-28.

Rodríguez, G 1999, La sabiduría del Kundur: Un ensayo sobre la validez del saber andino, Co-edición EBI-GTZ, Editorial Abya-Yala, Quito.

Rosales, CP 2003, ‘Soy andino y esta es mi magia: la Fiesta del Sol en Cayambe’, Ecuador Terra Incognita, July-August 2003, p. 24.

Sarmiento, FO 2017, ‘Syncretic farmscape transformation in the Andes: an application of Borsdorf’s religious geographies of the Andes’, in Re-conociendo las geografías de América Latina y el Caribe, eds. R Sanchez, R Hidalgo & F Arenas, Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, Santiago, pp. 35-53.

Sarmiento, FO 2016a, ‘Identity, imaginaries and ideality: understanding the biocultural landscape of the Andes through the iconic Andean lapwing (Vanellus resplendens)’, Revista Chilena de Ornitología, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 38-50.

Sarmiento, FO 2016b, ‘Neotropical Mountains Beyond Water Supply: Environmental Services as a Trifecta of Sustainable Mountain Development’, in Mountain Ice and Water: Investigations of the hydrologic cycle in alpine environments, eds. G Greenwood & J Shroder, Elsevier, New York, pp. 309-24.

Sarmiento, FO 2015, ‘On the Antlers of a Trilemma: Rediscovering Andean Sacred Sites’, in Earth Stewardship: Linking Ecology and Ethics in Theory and Practice, eds. R Rozzi, STA Pickett, JB Callicot, FST Chapin III, ME Power & JJ Armesto, Springer, New York, pp. 49-64.

Sarmiento, FO 2013, ‘Lo Andino: Integrating Stadel’s views into the larger Andean identity paradox for sustainability’, in Christopher Stadel Festschrift, ed. A Borsdorf, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Innsbruck, pp. 305-18.

Sarmiento, FO 2012, Contesting Páramo: Critical Biogeography of the Northern Andean Highlands, Kona Publishing, Higher Education Division, Charlotte, NC.

Sarmiento, FO 2003, ‘Protected landscapes in the Andean context: worshiping the sacred in nature and culture’, in The Full Value of Parks, eds. D Harmon & A Putney, Rowman and Littlefield Publishing Group, Lanham, pp. 239-49.

Sarmiento, FO, Ibarra, JT, Barreau, A, Marchant, C, González, J, Oliva M & Donoso, M 2019, ‘Montology: A research agenda for complex foodscapes and biocultural microrefugia in tropical and temperate Andes’, Journal of Agriculture, Food and Development, vol. 5, pp. 9-21.

Sarmiento, FO & Hitchner, S (eds) 2017, Indigeneity and the Sacred: Indigenous Revival and the Conservation of Sacred Natural Sites in the Americas, Berghahn Books, New York.

Sarmiento, FO, Ibarra, JT, Barreau, A, Pizarro, JC, Rozzi, R, González, JA & Frolich, LM 2017, ‘Applied Montology Using Critical Biogeography in the Andes’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 107, no. 2, pp. 416-28.

Sarmiento, FO & Viteri X 2015, ‘Discursive Heritage: Sustaining Andean Cultural Landscapes Amidst Environmental Change’, in Conserving Cultural Landscapes: Challenges and New Directions, eds K Taylor, A St Clair & NJ Mitchell, Routledge, New York, pp. 309-24.

Sarmiento, FO, Cotacachi, C & Carter, LE 2008, ‘Sacred Imbakucha: Intangibles in the Conservation of Cultural Landscapes in Ecuador’, in Cultural and Spiritual Values of Protected Landscapes, ed. JM Mallarach, vol. 2 in the series Protected Landscapes and Seascapes, IUCN and GTZ, Kaspareg Verlag, Heidelberg, pp. 125-44.

Sarmiento, FO, Rodríguez, G & Argumedo, A 2005, ‘Cultural Landscapes of the Andes: Indigenous and Colono Culture, Traditional Knowledge and Ethno-Ecological Heritage’, in The Protected Landscape Approach: Linking Nature, Culture and Community, eds J Brown, N Mitchell & M Beresford, IUCN: The World Conservation Union, United Kingdom, pp. 147-62.

Seligman, L & Fine-Dare, K (eds) 2019, The Andean World, Routledge, New York.

Vásquez-Fuller, C 1995, ‘Teogonía Andina’, in Revista Núm. 41, ed. Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana, Núcleo de Ibarra, CCE, Ibarra.

Vershuuren, B, Wild, R, McNeely, JA & Oviedo, G (eds) 2010, Sacred Natural Sites: Conserving Nature and Culture, EarthScan, London.

Whitten, N (ed) 2003, Millennial Ecuador. Critical essays on cultural transformation and social dynamics, Iowa University Press, Iowa City.

Wibbelsman, M 2005a, ‘Encuentros: Dances of the Inti Raymi in Cotacachi, Ecuador, Latin American Music Review, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 195-226.

Wibbelsman, M 2005b, ‘Otavaleños at the crossroads: Physical and metaphysical coordinates of an indigenous world’, Journal of Latin American Anthropology, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 151-85.

Wild, R & McLead, T (eds) 2008, Sacred Natural Sites: Guidelines for Protected Area Management, IUCN/UNESCO, Gland.

Willis, M & Seward, T 2006, ‘Protecting and preserving indigenous communities in the Americas’, Human Rights, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 18-21.