Sustainable Rural Development and Water Resources Management on a Hilly Landscape: A Case Study of Gonglaoping Community, Taichung, ROC (Chinese Taipei) (SITR6-7)

23.04.2021

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

National Chung Hsing University (NCHU); Soil and Water Conservation Bureau (SWCB)

DATE OF SUBMISSION

23/04/2021

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Chinese Taipei

KEYWORDS

Agricultural landscape · Eco-friendly farming · Water resources conservation · Dry stone masonry · Sustainable rural development · SEPLS

AUTHOR(S)

Chen-Fa Wu, Chen Yang Lee, Chen-Chuan Huang, Hao-Yun Chuang, Chih-Cheng Weng, Ming Cheng Chen, Choa-Hung Chang, Szu-Hung Chen, Yi-Ting Zhang, and Kuan Chuan Lu

C.-F. Wu · Y.-T. Zhang

Department of Horticulture of National Chung Hsing University (NCHU), Taichung City, Chinese Taipei

C. Y. Lee · C.-C. Huang · H.-Y. Chuang · M. C. Chen

Soil and Water Conservation Bureau (SWCB), Nantou City, Chinese Taipei

C.-C. Weng · C.-H. Chang

SWCB Taichung Branch, Taichung City, Chinese Taipei

S.-H. Chen

International Master Program of Agriculture, NCHU, Taichung City, Chinese Taipei

K. C. Lu

Gonglaoping Industrial Development Association (GIDA), Taichung City, Chinese Taipei

LINK

Abstract

The Gonglaoping community is located in Central Western Taiwan, with approximately 700 residents. The hilly landscape contains farmlands and sloping areas with abundant natural resources. Locals rely on the Han River system and seasonal rainfall for water supply for domestic use and irrigation. Uneven rainfall patterns and high demand for water has led to the overuse of groundwater and conflicts among the people. The surrounding natural forests provide important ecosystem services, including wildlife habitats and water conservation, among others; however, overlap with human activities has brought threats to biodiversity conservation. Considering these challenges, locals were determined to transform their community towards sustainability. The Gonglaoping Industrial Development Association (GIDA) and the Soil and Water Conservation Bureau (SWCB) joined hands to initiate the promotion of the Satoyama Initiative, playing catalytic roles in several implementations, such as establishing water management strategies based on mutual trust, rebuilding the masonry landscape, and economic development, forming partnerships with other stakeholders. This multi-stakeholder and co-management platform allowed the community to achieve transformative change, particularly in resolving conflicts of water use, restoring the SEPL, enhancing biodiversity conservation, and developing a self-sustaining economy.

Achieving sustainability in a SEPL requires the application of a holistic approach and a multi-sector collaborating (community-government-university) platform. This case demonstrates a practical, effective framework for government authorities, policymakers and other stakeholders in terms of maintaining the integrity of eco- systems. With the final outcome of promoting a vision of co-prosperity, it is a solid example showing a win-win strategy for both the human population and the farm- land ecosystem in a hilly landscape.

1. Introduction

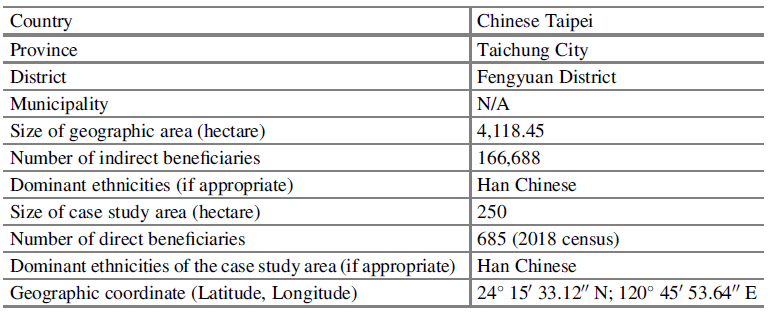

Gonglaoping, a hillside rural community in Fengyuan District, is situated in the central western part of Taiwan Island (Fig. 7.1), and has approximately 700 residents (Table 7.1). The main landscape is a terraced terrain with a total area of about 250 ha, containing approximately 100 ha of farmlands and 80 ha of foothills with abundant natural resources. The entire community is located within the upstream watershed of the Han River. River terraces are mainly formed by the Toukoshan Formation that originated from an alluvial plain and graduated to its current status due to orogenesis. The topography contains some flat areas with a mean elevation of 450 m. Thus, most residents have settled in flat areas but cultivate orchards on sloping hills. The geological origin of soil on the hills is from the Cholam Formation and lateritic river sediments. The Cholam Formation contains sandstone, mudstone and shale while river sediments consist of red clay, gravel, sand and other sediments. Both formations present good permeability.

The mean annual temperature of Gonglaoping is 21.6 oC, and weather patterns show distinct seasons with uneven rainfall patterns. The wet season starts in April and lasts until September with a mean monthly precipitation of 268 mm, while the dry season runs from October to March with a mean monthly precipitation of 42 mm. In recent years, droughts have become more frequent due to the impacts of climate change. Consequently, the terrace topography, low water retention capacity in the soil and unpredictable weather patterns have led to local production landscapes becoming increasingly vulnerable to the effects of regular droughts.

Due to uneven patterns of precipitation (e.g. the dry season occurring from October to March), the amount of water is insufficient to fulfil local demands; as a result, farmers extract groundwater for irrigation. Alongside climate change impacts, droughts are getting more and more serious as the dry season is lasting longer and leading to over-pumping of groundwater upstream. This situation threatens to jeopardise the water rights of humans and other fauna species living in midstream and downstream areas, and moreover causes water-related conflicts among commu nity people (SWCB Taichung Brach, 2017).

Fig. 7.1 Map of the country and case study area. Counter-clockwise from top left, relative location of the island of Taiwan (from Wikipedia), Taichung City (rose-coloured area), Fengyuan District (red outlined area), and Nansong Village (brown outlined area), where the Gonglaoping community (light orange-shaded area) is situated

Table 7.1 Basic information of the study area

Fig. 7.2 Bird’s eye view of persimmon orchard landscape (Source: NCHU)

About 200 years ago, Shiu Gong arrived to the area as a pioneer to explore the land and start cultivation. Afterwards, settlements began to form on the plain near the headstream of the Han River. The land near the headstream received sufficient water supply; however, the terrain’s slope, ranging from 32o to 52o, made it hard to further expand agricultural activities. To stabilise the hillside soil, the ancestors collected available materials (e.g. stone, and pebbles) in or near the area for construction. Stones were piled up in the form of retaining walls and formed into dry masonry embankments in the valley, which over time formed an iconic socio-ecological production landscape (SEPL).

Prior to the 1940s, locals mainly grew food crops, such as sugar cane, rice and potatoes for subsistence use. After 1945, Chinese Taipei’s GDP started to increase and the economy developed quickly, causing market demand for food crops to plummet. Given that the micro-climate in Gonglaoping is quite suitable for the growth of fruit trees, farmers began to convert farms to orchards, with trees such as citrus fruits, persimmon and lychee. Persimmon, a temperate fruit tree, is typically grown on the hilly farmlands. Persimmon orchards reveal different colour themes by seasons. In spring, a cluster of green leaves grows on the thin branches, while in summer, trees start fruiting. In autumn, the persimmons gradually mature, and the fruit itself turns dark orange. When winter comes, the hibernating period of the persimmon trees begins, with the colour of leaves turning from green to red or golden yellow. The whole hillside shows a unique production landscape mosaic with masonry stone embankments and vibrant red-golden-yellow colour (Fig. 7.2) (SWCB Taichung Branch, 2017).

In 1990, farmers in Fengyuan District established the 5th Citrus Agricultural Production and Marketing Group. The group often holds training workshops or forums for members to exchange experiences and learn from each other. In order to reduce production costs, members set up a joint venture agreement to purchase a citrus fruit cleaning and sorting machine, refractometers (Brix meters) and other instruments. They also invited online marketing experts to teach members how to operate e-commerce. In this way, farmers gained the capacity to allow them to engage in direct sales online, reduce the cost of agency sales, access consumers’ demands and feedback effectively, and increase profit margins. In 2009, the 5th Citrus Agricultural Production and Marketing Group of Fengyuan District won the national top-ten prize awarded by the Council of Agriculture, Chinese Taipei (COA). Owing to the high-quality fruit and brand name recognition, the sale values and prices of the fruits increased substantially, benefiting local farmers directly through increase in income.

Urban dwellers often have more job opportunities and better salaries. Since the Gonglaoping community is not far from downtown Taichung, young people tend to migrate to the city, causing problems such as an aging labour force and industrial recession. Currently, residents of Gonglaoping aged 60 or above account for 20% of the total population. In other words, the community has fallen into the pitfall of an aging labor force due to youth migrating out.

To respond to the challenges mentioned above, the Gonglaoping community committed to seek foster and apply a plan that could transform the SEPL toward a sustainable future. Locals were also determined to preserve and pass down traditional culture that emphasises humans living in harmony with nature. The embedded culture and beliefs have not only strengthened the sense of coherence but also have aided the community in establishing a system based on mutual trust, which has been beneficial to achieving the desired results. Therefore, it was quite essential to have a holistic approach that could sustain equilibrium among agricultural activities, water resources management, biodiversity conservation, local economic development and quality of life, as well as an approach that operated based on co-management.

2 Description of Activities

Transformative change refers to “.. .fundamental, system-wide change that includes consideration of technological, economic and social factors, economic, and social factors, including in terms of paradigms, goals and values” (Bélair et al. 2010; IPBES 2019). Referring to the principles above, the Gonglaoping community, National Chung Hsing University (NCHU) and the Soil and Water Conservation Bureau (SWCB), a government agency, joined hands to implement a project based on the Satoyama Initiative, to enable transformative change towards the desired goals of wellbeing and sustainability through several leverage points, which are:

(1) establishing water management strategies and a co-management system;

(2) restoring the masonry production landscape (SEPL);

(3) enhancing biodiversity conservation;

(4) developing products/services for a sustainable economy; and

(5) forming a multi-stakeholder operating

Under such a multi-sectoral, collaborative structure (government-university-com- munity), an array of actions has been carried out to achieve sustainability of the SEPL. These include forest and wildlife-habitat restoration in the upstream catchment area, eco-friendly farming practices to maintain healthy agricultural ecosystems, promotion of smart allocation and mitigation of over-use of water resources, preservation and re-introduction of traditional wisdom (e.g. dry stone masonry), and development of community industry to enhance local incomes. Related activities are described in the following sections (SWCB Taichung 2017; SWCB 2018).

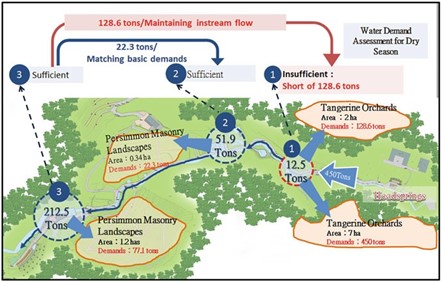

2.1 Establishment of Water Management Strategies and System

Due to the unbalanced nature of seasonal precipitation, the amount of water available is often insufficient to fulfil local demand in winter. As a result, over-pumping of groundwater occurs, causing water-related conflicts among community people. Accordingly, the community requested funding and technical support from SWCB. SWCB took the lead role (catalyst) in creating a plan to dredge severely silted ponds and build up reservoirs. The total volume of reservoirs was expanded from 56 to 416 tons. The reservoirs store rainfall in the wet season to supply irrigation water in summer and winter. As shown in Fig. 7.3, the smart water resources management and recycling system allocates water resources precisely and effectively. For example, if the water level of the first and second ponds drop, the system would flag a signal to the pumping motor and the water in the down- stream number three pond would be pumped up and distributed to the first and second ponds. Additionally, the pumping system is powered by solar energy, a clean energy that does not produce any greenhouse gases, known to be responsible for climate change.

To mitigate low soil water retention capacity, vegetated buffer strip cultivation was adopted to improve the physical and chemical characteristics of soil, in particular, to increase organic matter content thereby improving soil drainage and aeration. This approach can also prevent root damage due to sudden changes in soil temperature. Grass roots also retain soil moisture and nutrients, thus preventing rapid leaching of nutrients. The decomposition of grass roots supplies a large amount of carbon and nitrogen to beneficial micro-organisms, which enhances the soil’s microbial cycles. In Gonglaoping, vegetated buffer strip cultivation is practices on 91% of farmlands. The other 9% is sloped land that can be difficult to artificially weed. However, the orchard owners counted on the advantages of vegetated buffer strip cultivation to control weeds without using herbicides. Farmers have recognised that vegetated buffer strip cultivation improves soil properties, and contributes to environmental and ecosystem protection.

The community formed the Han-River Neighbourhood Watch that patrols the area regularly to voluntarily guard the headspring water, monitor the streamflow, and to coordinate water resources allocation (Fig. 7.4). Major duties include, but are not limited to: (1) monitoring of ecosystem health; (2) maintenance of a clean community; and (3) accounting for the regular cleaning and maintenance of water reservoirs. The neighbourhood watch is also responsible for the maintenance of weather stations and water level gauges, as well as data collection and monitoring. Community members also attend regular meetings, report maintenance results, exchange information on experience, and deal with any water-related issues on a weekly basis (every Tuesday night). Through this process, locals were able to foster a co-management system based on mutual trust to resolve conflicts and use water effectively.

Fig. 7.3 The water resources management and recycling system for the Han River’s upstream catchment area

Fig. 7.4 Formation ceremony of the Han-River Neighbourhood Watch (Source: GIDA)

2.2 Restoration of Masonry Production Landscapes

On 21 September 1999, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake occurred in central Taiwan, becoming the most devastating natural disaster in the island of Taiwan in the twentieth century. The Gonglaoping community was traumatised. Homes were damaged; masonry embankments collapsed, and roads and hiking routes were destroyed. After the earthquake, the community initiated a series of post-disaster recovery and reconstruction projects. In order to strengthen community cohesion and set clear development goals, the Gonglaoping Industrial Development Association (GIDA) took the lead in the implementation of a Rural Regeneration Project funded by SWCB. Likewise, SWCB initiated the Rural Empowerment Project in 2004 aimed at enhancement and capacity building for rural communities. Under this project, rural communities were requested to analyse their requirements and demands first, then determine their implementation capacity and make a plan for training to narrow the capacity gap. In April of 2010, the Gonglaoping community began the procedure to plan training courses. Subsequently, a four-stage, 92-h rural community development course was implemented for community members. In particular, the course taught how to document community life, agricultural production, ecology, culture and other resources, and then facilitated the development of a vision and goals independently. Through this capacity building programme, the community was empowered and the benefits of a participatory, community-led approach were clearly understood. In late 2012, the community completed and got approval for its rural regeneration plan proposal. After implementation of the rural regeneration plan, the Gonglaoping community actively and independently applied government funds to improve the community environment, conduct cultural and ecological surveys, implement community guide training programmes, and organise activities to invigorate the citrus fruit industry every year.

Masonry production landscapes are situated along the upper Han River. The trails in the vicinity were damaged by the earthquake and hence were dangerous for community members to use, causing particular inconvenience to elderly people. GIDA actively sought government funds to restore the masonry walls at the head- spring of the Han River. The locals reached an agreement to use a participatory design method to renovate embankments on both sides and to restore the unique masonry SEPL. To date, the community has repaired about 3100 m of the destroyed masonry walls, and restored four ha of production areas, with an annual production capacity of 120 tons of persimmon. Gonglaoping has also held several dry masonry construction workshops and invited masonry craftsmen to teach the local youth (Fig. 7.5). The participating community members stated that the theoretical concepts of masonry methods are not difficult to learn; however, considerable effort and skill is required for implementation. Through sharing the experiences and key skills of master craftsmen, the community not only promoted a useful construction method, but also ensured the transmission of knowledge on traditional masonry methods. Doing so ensures that the Gonglaoping community implements low-impact practices for slope stability, achieves resource recycling, maintains environmental capacity and passes on traditional heritage to the next generation.

Fig. 7.5 Dry masonry construction workshops (Source: NCHU and GIDA)

2.3 Enhancement of Biodiversity Conservation

From 1970 to 2000, large amounts of chemical fertilisers were applied to increase yields in agricultural production, bringing cumulative damage to the environment and associated ecosystems. Pesticides and fertilisers were washed into the river and irrigation systems through rain, seriously threatening fish and other aquatic organ- isms. Excessive use of hazardous chemicals contaminated soil and groundwater, bringing health risks to local farmers and consumers.

Once the community members started to realise the harmful impacts of chemicals on health and the environment, they decided to seek professional assistance. A series of training courses on orchard management was held by experts from COA, including topics such as eco-farming practices, rational application of fertilisers and safety standards for pesticide application (Fig. 7.6). Community residents also worked together with various academia, government agencies, and NGOs to educate locals regarding the long-term impacts of chemical fertilisers and pesticides on soil productivity, farmland ecosystems, harvest quality and human health. Moreover, local residents call for meetings if any related issue needs to be resolved or any assistance is required (Fig. 7.6). This communication mechanism can be seen as the prototype of the future Communications, Education, and Public Awareness (CEPA) strategy that was to be implemented.

The Gonglaoping community began its rural regeneration plan in 2012, funded and supervised by the SWCB. Under the project’s operating framework, the com- munity has held nine “Training of Trainers” (TOT) workshops, training locals on organic fertilisers and pesticides, as well as their development and use. Lecturing content included the applications of Trichoderma, a type of biological fertilisation, to treat plant disease and a biocontrol practice for lychee stink bugs involving intro- duction of Anastatus japonicus (wasps). Currently, eco-friendly farming (e.g. persimmon, citrus fruits, and longan) has been expanded to 15 ha, which is about 12.5% of the total production area.

The community set up a water quality monitoring system in 2017 to prevent pollution from agricultural runoff and started making long-term records of observations, particularly examining the streamflow and water quality of the upper, middle and lower streams. Indicators include conductivity, pH value, dissolved oxygen (DO), nitrate concentration, total phosphorus and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD). Various fish and amphibians have been spotted after the monitoring system was put in place, such as the Taiwan striped barb (Acrossocheilus paradoxus), Formosan stripe dace (Candidia barbata), goby (Rhinogobius rubromaculatus), carp (Carassius auratus), temple tree frog (Kurixalus idiootocus), Brauer’s tree frog (Polypedates brauerii), Latouchte’s frog (Hylarana latouchii), Gunther’s frog (Hylarana guentheri), ornate narrow-mouthed toad (Microhyla fissipes), Fujian large-headed frog (Limnonectes fujianensis), and rice field frog (Fejervarya kawamurai).

Starting from the 1960s, locals began to realise the importance of water and soil conservation, and considered stopping the cultivation of crops in the upstream catchment area of the Han River. Afterward, the settlement gradually moved down- stream for agricultural activities. Compared to the orchards situated on the terraces, lands in the upstream area required much more effort to grow and manage crops. Besides, farmers were getting older and their suitable farming areas were slowly shrinking. Abandoned lands increased due to fewer disturbances from human activities and hence have turned into secondary forest by natural forest succession. This process created wildlife habitats and made this region abundant with biodiversity. After a 50-year natural succession, 109 ha of natural forest has been established. Field surveys have documented 54 species of plants and 30 avian species.

Additionally, stone masonry embankments on the hillside are constructed by a triangular stacking method, called the traditional herringbone method. The stone walls with irregular cobbles have cavities of different sizes, providing spaces and refuge for small animals to hide and plants to grow. The common species include the Taiwan Maesa (Maesa formosana Mez.), Taiwan scouring rush (Equisetum ramosissimum Desf.), skunk-vine (Paederia cavalerieri auct. non H. Lev.), sword brake (Pteris ensiformis Burmann), tuberous sword fern (Nephrolepis brownii (Desv.) Hovenkamp & Miyam), acuminate leaf morning glory (Ipomoea indica (Burm. f.) Merr.), five-striped blue-tailed skink (Plestiodon elegans), Swinhoe’s japalure (Diploderma swinhonis), gossamer-winged butterflies and ants, among others.

Fig. 7.6 Training in eco-friendly farming practices (Source: GIDA)

2.4 Development of a Self-sustaining Economy

Since its establishment, GIDA has actively applied for funding to hold industrial revitalisation activities to attract investors, buyers and tourists. For example, the Citrus Industry and Culture Festival in 2016 had at least 3000 visitors. It increased local incomes by 30% through the sale of agricultural products with revenue of about 300,000 NTD (roughly 10,000 USD). The hotel accommodation rate also went up by 20%. The increased visits and recognition of tourists has enhanced the local youths’ confidence in business opportunities and career possibilities in their hometown.

Since 2013, when the first youth returned home, the total number has continued to rise, reaching ten. The young generation of farmers who have moved back to their hometown have insisted on practicing organic and eco-friendly farming, growing citrus fruits and persimmons with the aim of protecting natural resources and the environment. Although mature fruits (e.g. citrus) were not attractive looking and could not sell at a good price during the transition period, local famers unleashed their creativity to make a wise turn. Instead of making money by selling traditional table fruit, they developed two post-harvest processed products, organic persimmon leaf tea and organic citrus gummy candies (Fig. 7.7), that could earn more profit. Both products are made from local persimmons and citrus fruits that are cultivated using organic farming methods. The tender persimmon leaves that grow in spring are carefully selected for processing. Persimmon leaves are highly nutritious and rich in protein, amino acids and multi-vitamins. The tea is also acknowledged as one of Rural Goodies” in Taiwan Island (i.e. good products from rural communities) by the SWCB, generating a revenue of up to 370,000 NTD (12,300 USD) annually. In addition, the organic citrus gummy is a soft candy made from local tangerine oranges. It is rated as one of the ten best souvenirs in Taichung by the media and can now be bought on the Taichung city government’s e-commerce platform, generating annual revenue of 660,000 NTD (21,900 USD).

Under the leadership of the youthful chairman of GIDA, the Gonglaoping community has begun to offer a variety of lively activities. The community operates four in-depth agricultural tours based on the four seasons (i.e. spring, summer, fall, and winter) so that people from all over the world can better understand the local characteristics of Gonglaoping. Local industrial development and promotional events include “Spring Tour in Gonglaoping – Orange Blossom Viewing and Citrus Essential Oil DIY”, “Lovely Lychee in Gonglaoping – Fengyuan Lychee Festival and Outing”, “Autumn Praise: Gonglaoping Persimmon Banquet and Rural Chinese Orchestra Concert”, and “Winter-When-Tangerines-Turn Red–Gonglaoping Picnic Party.”

Fig. 7.7 Organic agricultural products of the Gonglaoping community (Source: GIDA)

3 Results

By engaging in cross-sector collaboration with multiple stakeholders, including SWCB, the National Chung Hsing University (NCHU) and other local groups, the following achievements have been made:

(1) Resolving conflicts surrounding water use by increasing water storage capacity and reducing groundwater consumption during the dry season

Rainfall patterns in Gonglaoping are uneven by seasons. The rainy season is in summer while the dry season is in winter. Both the persimmon growing period (summer) and the dry season (winter) require a lot of water for irrigation. However, the Han River cannot provide an adequate amount of water; thus, farmers often solved the problem by pumping groundwater, which affects the water and groundwater usage of residents living midstream and downstream. The community carried out an expansion of the original water retention capacity and also built terraced-type, ecological engineered reservoirs by consulting experts in SWCB and NCHU. The total volume of reservoirs was expanded from the original 56 tons to 416 tons. Based on an estimation, if the reservoirs are filled to capacity during the rainy season, they would able to match water demand during the dry months (February and March), reducing the groundwater used to an amount equivalent to that used for 5 weeks. Accordingly, the groundwater extraction volume was reduced from the original 510 to 93 tons. On the other hand, irrigated areas that are supplied by the Han River increased from 10 ha to 14 ha (17.5% of the catchment area) and persimmon production also increased by about 120 tons. This construction was a win-win strategy to alleviate the problem of insufficient irrigation and to conserve wildlife habitats.

(2) Restoring traditional masonry in the SEPL

Hillside orchards represent a unique SEPL with multi-layer stone masonry embankments. The embankments conserve water, stabilise slopes and provide refuge for various organisms. The holes and cavities between the embankments are home to a variety of small creatures. Vegetated buffer strip cultivation also benefits the environment in many ways, including reducing herbicide use, alleviating soil erosion, balancing soil moisture, increasing soil nutrients and maintaining healthy soil ecosystems.

(3) Empowering, enhancing and sustaining local operations through the leadership of a community-led NGO, the Gonglaoping Industrial Development Association

The Gonglaoping Industry Development Association, which was established in 2004, plays a vital role in sustainable water resources management. The association has experienced seven directors. All previous directors continue to participate in community industrial development. The association meets regularly every Tuesday night to discuss development affairs and to bring all locals together to promote unity in industrial revitalisation (Fig. 7.8). For the protection and rational use of the Han River’s water resources, the association plays a role in the coordination of the sustainable management and utilisation of water resources. To mitigate conflicts in the processes of irrigation, community members reached an agreement to set up a neighbourhood watch to patrol the Han River and drafted a convention to conserve the water resources of the Han River and manage the community.

(4) Enhancing benefits of green industries: the new economic and ecological values of organic industries

The youth have developed organic products such as persimmon leaf tea and citrus gummy candies to add new economic value to local industries. In particular, they have adapted innovative post-harvest processing technologies to make new healthy foods. The persimmon leaf tea can earn twice the profits of sale of the traditional agricultural product, while the revenue from citrus gummy candies is even better with a boost of ten times the profit. Because both products emphasise organic concepts and zero fertiliser residue, the success of these products provides solid evidence on the benefits of organic farming practices, brings new insights and motivates transformative change in climate smart agricultural practices. The eco-friendly farming practices adopted by the com- munity represent a true win-win strategy to maintain water quality, conserve biodiversity and sustain the income of local people.

The cumulative number of visitors in 2017 was about 1,450, with an estimated 25% return rate and the net economic benefit of 1.27 million NTD (421,000 USD). This implies that the innovations in the community activities in Gonglaoping are able to constantly attract customised groups.

4 Discussion

The development of foothills often requires slope stabilisation. The dry masonry piled up with in situ materials not only solves the problem of stone placement after site preparation, but also has good water permeability and generates habitats for fauna and flora. The masonry SEPL presented has many valuable functions, including soil and water conservation, restoration of the practice of low–impact masonry, maintenance of biodiversity, creation of refuge for organisms, integrated applications of traditional knowledge, and promotion of tourism.

Constrained by micro-climatic conditions, the Gonglaoping community is often short of water for irrigation in dry seasons. Fortunately, most community members are aware of and understand particular issues; they show empathy towards each other. Based upon mutual trust, locals have established a strategic, decision-making routine on a weekly basis. Their scheme divides water allocation by divisions and time slots, so that all orchards can be irrigated to maintain vigorous growth. Also, the water allocation plan is reviewed periodically and the need for revision determined. This helps avoid conflicts caused by competing water sources and mitigates the over- pumping of groundwater in the dry season. Hence, this communication mechanism is an effective strategy that provides incentives to reach consensus.

The Gonglaoping community is situated on the upper Han River. Any over-use of fertilisers and pesticides could impact negatively on water quality and risk community health. Moreover, the irrigation relies on river water supply, leading to a vicious cycle. The farmers understand that high quality fruits can only be produced in healthy ecosystems with good water quality. Thus, in rejecting the use of herbicides and adopting eco-friendly farming practices, the community has been able to maintain the ecological environment and water quality near the Han River. Several local farmers have cooperated with government agencies to apply Trichoderma instead of pesticides and chemical fertilisers, and also perform lychee stink bug biocontrol by introducing Anastatus japonicus (wasps).

In the process of post-disaster recovery and restoration, the community created numerous job opportunities in the field of leisure agriculture and has hosted a variety of activities and events to lure visitors from urban areas. These opportunities have been able to attract young people to move back to the rural areas. Besides, the ideas proposed by these returning youths have been accepted by the community, and they participate in local affairs, hence becoming more deeply rooted in the community affairs. In 2016, the chairman of GIDA was elected. The community believes that passing down authority to the younger generation opens up a new era and broadens the path to future prosperity. Thus, they voted for a youth to serve as the new chairman. The new chairman and other returning youths have been led by the former president, which has helped them to quickly become familiar with community affairs. Also, they have altered the traditional way of organising events by integrating online marketing, social media and other trendy concepts. This makes the activities more dynamic and shines a light on the Gonglaoping community’s features.

GIDA has shown a strong connection with locals, and actively proposes improvement plans while acting as a “glue” agent and cooperating closely with various governmental agencies, the private sector, and other NGOs. This multi-stakeholder platform enables transformative change and enhances related movements toward sustainability in SEPLs. Current associated stakeholders include the Taichung Branch of SWCB, Agricultural Bureau of Taichung City Government, NCHU, Fengyuan District Farmers’ Association, Agricultural Research and Extension Station, and the Taiwan Agricultural Chemicals and Toxic Substances Research Institute. Although the Gonglaoping community still needs external funding (e.g. governmental incentives or competitive grants), its common goal is to sustain economic revenue and ultimately reach a self-sustaining status in the future.

5 Conclusions: Key Messages

Achieving the sustainability of SEPLs not only requires the application of a holistic approach, but also cross-sector collaboration (community-government-university). The key messages of this case are:

(1) The masonry SEPL highlights many valuable functions, including soil and water conservation, a low-impact practice for slope stabilisation, maintenance of biodiversity, preservation of traditional wisdom and

(2) Constrained by micro-climatic conditions, the Gonglaoping community is often short of water supply for irrigation in the dry seasons. Locals have learned to facilitate a strategic decision-making routine, with the water allocation plan reviewed and revised weekly so that all orchards can be irrigated for In addition, this mechanism helps avoid conflicts of water use and halts overuse of groundwater in dry seasons. The key element of such effective operation is mutual trust among community residents.

(3) Because of the success of organic products, locals are more willing to practice eco-friendly farming, which is a true win-win strategy to sustain water quality, biodiversity and the economy.

Hence, we are confident that the Gonglaoping community could serve as an example for practical implementation of the Satoyama Initiative on hillside, agricultural landscapes in East Asia.

Acknowledgements Sincere gratitude and thanks are expressed to local residents, farmers, and different groups of the Gonglaoping community for providing valuable assistance for the study. We have prepared associated contents as an IPSI case study, which we are planning to submit to the IPSI Secretariat. The work was supported by Rural Regeneration fund of the Soil and Water Conservation Bureau, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Chinese Taipei).

References

Bélair, C., Ichikawa, K., Wong, B. Y. L., & Mulongoy, K. J. (Eds.). (2010). CBD Technical Series: Sustainable use of biological diversity in socio-ecological production landscapes: Background to the ‘Satoyama Initiative for the benefit of biodiversity and human well-being. Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Technical Series no. 52184.

IPBES. (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. In S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio, H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. R. Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, & C. N. Zayas (Eds.), IPBES Secretariat. Bonn: IPBES.

Natori, Y., Dublin, D., Takahashi, Y., & Lopez-Casero, F. (2018). SEPLS: Socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes—experiences overcoming barriers from around the world. Tokyo: Conservation International Japan.

SWCB Taichung Branch, COA., R.O.C. (Chinese Taipei). (2017). 2017 rural community intelligent disaster prevention and Satoyama initiative practice in hillside area. Taichung City: SWCB Taichung Branch, COA.

SWCB Taichung Branch, COA., R.O.C. (Chinese Taipei). (2018). 2018 strategy development and implementation of the Satoyama initiative in Chung-Miao rural communities. Taichung City: SWCB Taichung Branch, COA.

Note

The opinions expressed in this chapter are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNU-IAS, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent.

Open Access This chapter is licenced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO Licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to UNU-IAS, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The use of the UNU-IAS name and logo, shall be subject to a separate written licence agreement between UNU-IAS and the user and is not authorised as part of this CC BY 3.0 IGO licence. Note that the link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the licence.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation, or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.