Sustainable development of Taiwanese indigenous tribes in accordance with Seediq tradition of Gaya

11.11.2022

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

Soil and Water Conservation Bureau (SWCB)

OTHER CONTRIBUTING ORGANIZATIONS

East Coast Tribal Industry Promotion and Development Association Crop.

DATE OF SUBMISSION

02/09/2022

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Chinese Taipei

KEYWORDS

Ancestral rule of Gaya, indigenous culture, hunting, butterflies, eco-friendly agriculture

AUTHORS

Yen-Cheng Chiang3, Chen-Yang Li1, Jung-Chun Chen2, Ming-Cheng Chen1, Hsin-Yen Peng2, Chia-Hsun Wang4

1. Soil and Water Conservation Bureau (SWCB), Nantou City, Nantou, Taiwan (R.O.C.)

2. Nantou Branch, Soil and Water Conservation Bureau (SWCB), Nantou City, Nantou, Taiwan (R.O.C.)

3. Department of Landscape Architecture, National Chiayi University (NCYU), Chiayi, Taiwan (R.O.C.)

4. East Coast Tribal Industry Promotion and Development Association Crop., Renai Township, Nantou, Taiwan (R.O.C.)

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Abstract

The Seediq people of Alang Tongan (Ren’Ai Township, Nantou County, Taiwan) uphold the tradition of Gaya—ancestral rules based on respect for all things—and lead a life of self-sufficiency while coexisting with nature. However, with the occurrence of wars; cultural, industrial, and economic changes; and hazards (e.g., earthquakes and landslides) in the past 100 years, the tribe’s ecology and development were ruined, posing challenges to the local industry. Subsequently, the young members of the tribe left it to search for livelihoods elsewhere, resulting in a cultural decline, population aging, and the abandonment of the tribe’s land.

However, the young people who returned to the tribe have resolved to reclaim their traditional culture and rediscover other lost indigenous cultures. The first steps were restoring traditional homes and rituals, which helped to rebuild tribal cohesion and earn the recognition of tribal elders. The people of Alang Tongan continued the education and training of local talents through interviews with tribal elders, and they partnered with public agencies to restore damaged ecological environments and lost cultures. Finally, the tradition of Gaya Mssbarux—payment through labor—was combined with a modernized industry chain platform to solve problems related to the tribal industry and youth employment.

Alang Tongan’s strategies for improving the tribe’s livelihood involved restoring the tradition of Gaya and the spirit of coexistence with nature, restoring traditional communal farming cultures, establishing farming teams, promoting eco-friendly agricultural practices, and restoring traditional indigenous crops. Furthermore, community topics were discussed by incorporating traditional deliberation systems into modern systems of representation and inviting local stakeholders to participate in decisions on the direction of the tribe’s development. These efforts were also aligned with the six ecological and socioeconomic perspectives of the Satoyama Initiative. Alang Tongan has since progressed from recovering to improving itself while upholding the spirit of the Satoyama Initiative to establish a sustainable Seediq tribe that promotes a sustainable Taiwan.

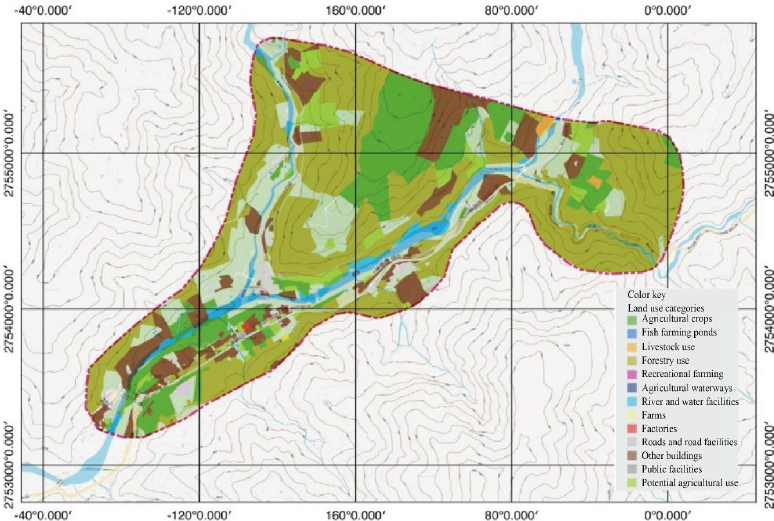

Socioeconomic and environmental traits

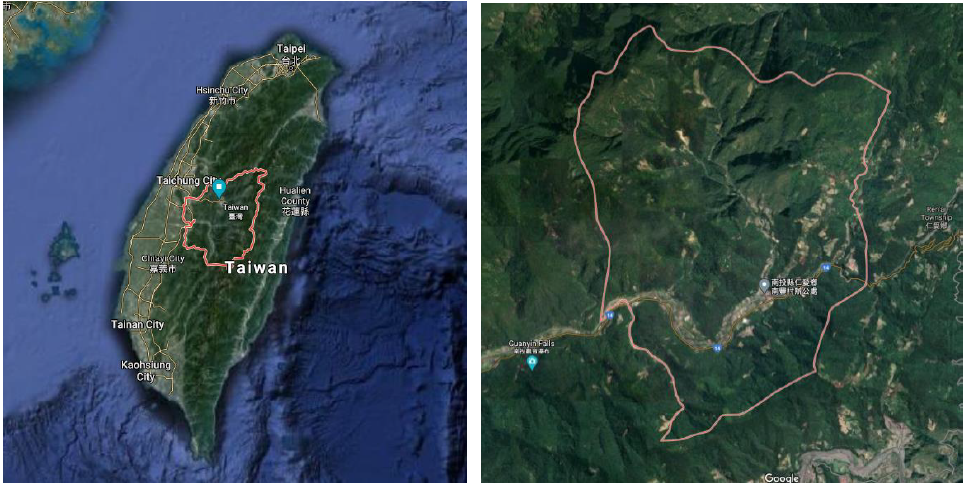

Alang Tongan tribe of the Seediq People is situated in the Nanfeng Village, Ren’ai Township of Taiwan’s Nantou County (Figure 1); it is approximately 15 km east of Puli Township, the county’s third largest town. The Alang Tongan terrain spans 4,232 ha and is located at 700 to 1,000 km above sea level; it contains mountains, virgin forests, hills, rivers, waterfalls, valleys, tea gardens, and screen house farms. The region receives an annual rainfall of 2,100 mm. Temperatures vary considerably between night and day, and the average temperature is 18°C; the hottest season is from June to September, during which temperatures can reach 33°C. The region has three settlements, which are collectively called Alang Tongan and distributed along the river Bakei that runs through the entire region and near Provincial Highway 14. More than 95% of the residents are Sediq Tgdaya.

The Bakei is the main river that flows through Alang Tongan; its two tributaries originate from the mountains Dgyaq Pgdiyan and Nandongyan. In this area, the upstream reaches are densely forested, and the rivers and valleys are fertile habitats for numerous species of frogs, fireflies, and dragonflies, featuring an abundance of butterfly resources that allow for the formation of beautiful and natural butterfly trails. Since Taiwan was under Japanese rule, this area has been renowned as a destination for collecting butterfly samples, and numerous older residents relied on hunting and selling butterflies as their livelihood. The subsequent decline of the butterfly industry and increasing awareness of ecological conservation motivated numerous tribes to reexamine topics relating to local humanities and conservation of natural resources and to reflect on ecological issues. From April 2011 to March 2012, the Endemic Species Research Institute (ESRI) recorded 120 species of butterflies in their monthly survey of butterfly trails along the Nanshan River: specifically, the institute detected 15 species from the Hesperiidae family (13%), 17 species from the Papilionidae family (14%), 13 species from the Pieridae family (11%), 24 species from the Lycaenidae family (20%), and 51 species from the Nymphalidae family (42%).

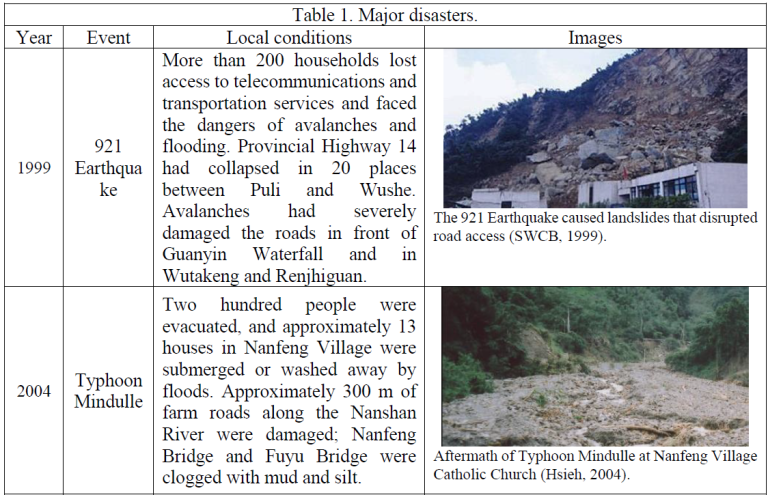

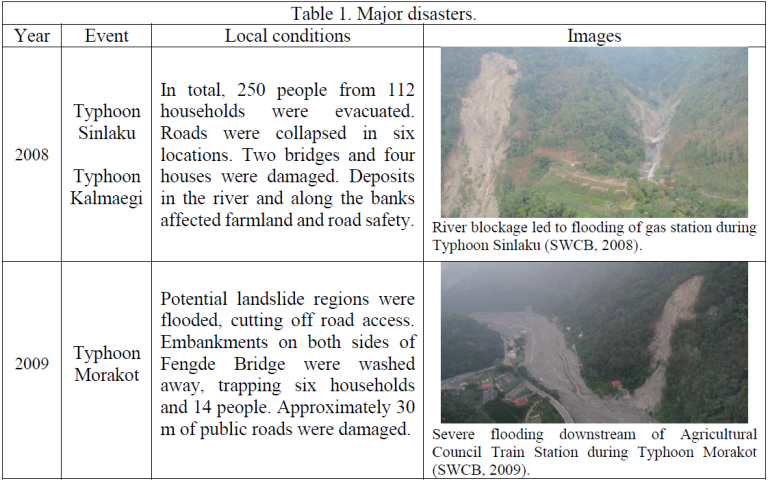

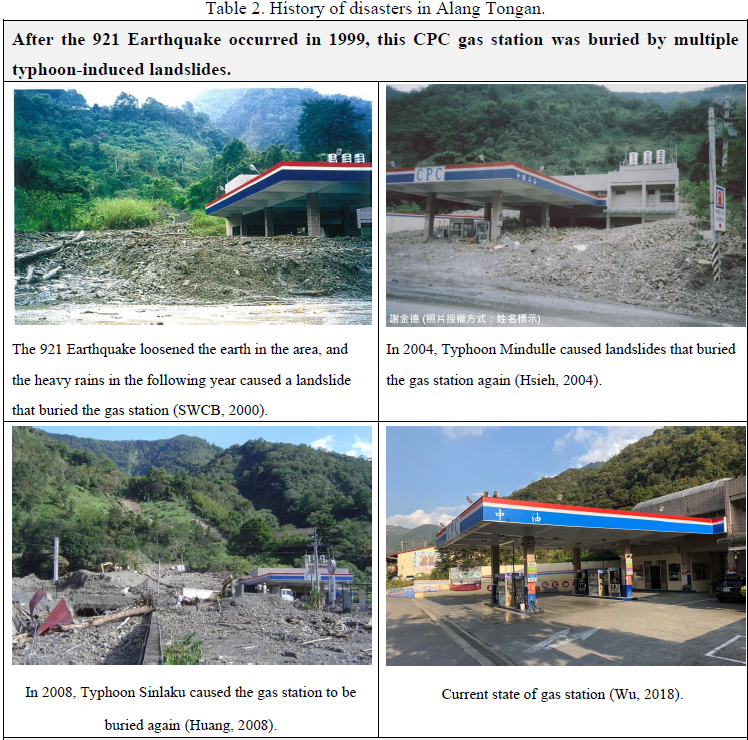

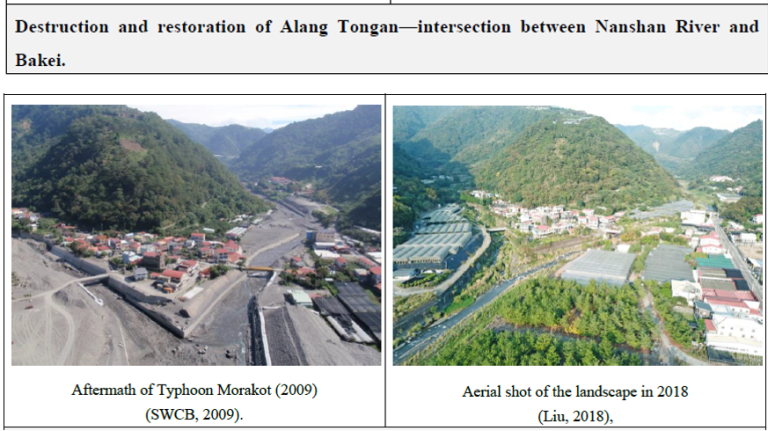

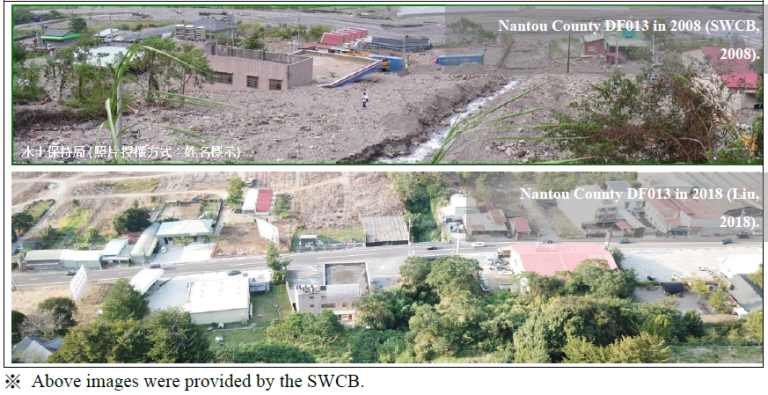

Alang Tongan lies close to riverbanks, and increasing climate change and overdevelopment contributed to building collapses and soil loss during the 921 Earthquake that occurred in 1999. When Typhoon Mindulle and Typhoon Morakot occurred in 2004 and 2009, respectively, heavy rains that affected the area caused landslides and avalanches (see Table 1 and Figure 2). Large amounts of collapsed earth and rocks built up in the riverbed, severely damaging the natural ecological and production landscapes (Table 2).

Interactions between local people and nature

The Tgdaya—the Seediq people who settled in this region—settled in Alang Tongan village several hundred years ago and have continued to pass down their ancestral rules, which are referred to as Gaya. Gaya—the code of traditional and social conduct that is applied to the Seediq people—can be regarded as the law of the Seediq people because it governs their cultural customs, morals, taboos, ritual customs, farming and production practices, and hunting culture. Gaya is the product of generations of interactions between the Seediq ancestors and nature, and it represents a set of rules for coexisting with nature on the basis of the concept that land is shared by all living things. Gaya also does not incorporate the concept of money; instead, the Tgdaya implement a bartering system involving the exchange of goods or assistance.

The Tgdaya people farm from spring to autumn, and they practice slash-and-burn agriculture and crop rotation. Their main crops are millet, quinoa, sweet potatoes, taro, and beans. After several years of farming, they allow the fields to lie fallow while they engage in planned reforestation and ecological restorations. During the winter, they hunt in the mountains and strictly conform to the Gaya codes of respect for the mountains and take only what they require.

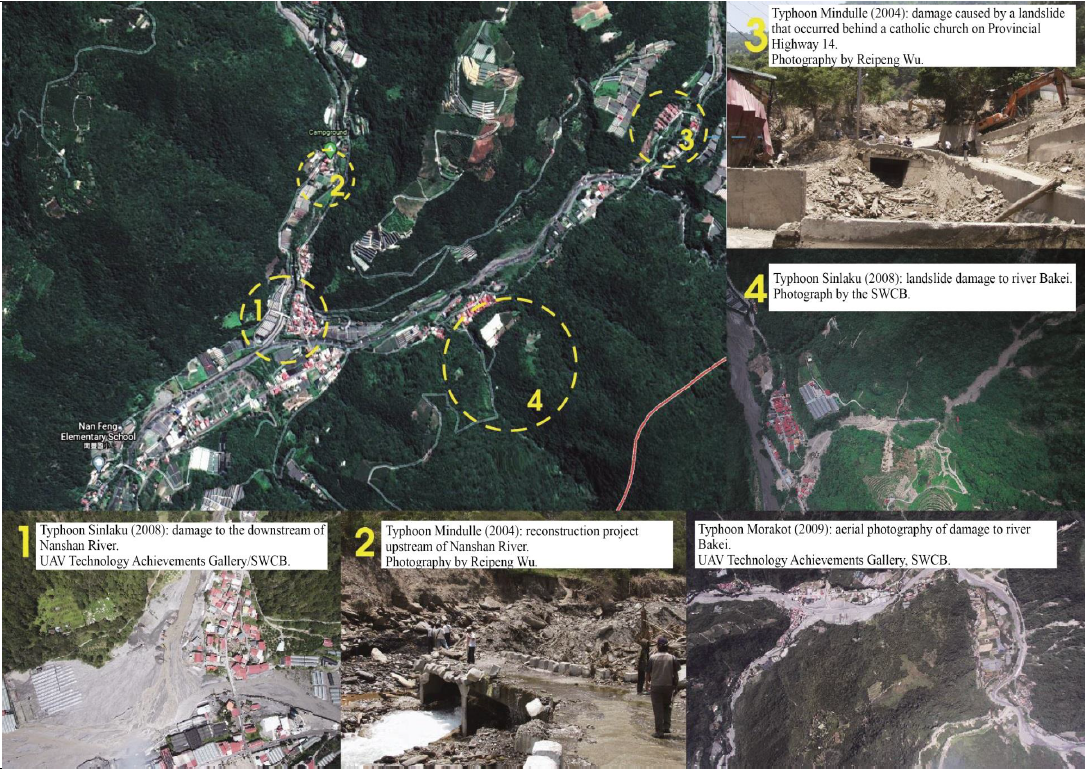

During the Japanese rule of Taiwan from 1895 to 1945, indigenous peoples were forced to leave their ancestral lands and live in concentrated settlements following the Musha Incident. The Japanese government rigorously promoted the farming of rice in paddy fields; they dug canals and flooded the terrain to create paddy terraces in the mountains. Subsequently, tribal landscapes began to resemble today’s agricultural landscapes. After the government of the Republic of China took over Taiwan in 1945, the introduction of a monetary economy altered the indigenous people’s traditional concepts about life and production and shifted their perception of land from public property to a private one. To increase their harvest, the Tgdaya people began to farm high-profit cash crops, and some farmers engaged in exploitative planting practices that caused soil exhaustion. The rise of Taiwan’s industries led to decreasing agricultural incomes, which was compounded with the rural exodus of the young members of the tribe; consequently, tribal lands were gradually abandoned or rented out as elevated greenhouses. Furthermore, large areas of the mountains were converted to grow vegetables, tea plants, and fruits (Li, 1983). The area now consists mostly of greenhouses for growing vegetables and flowers (Figure 3).

Basic principles

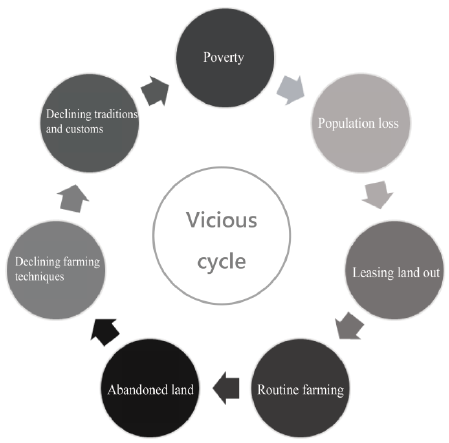

Following a century of changes, natural disasters, and economic restructurings that have led to ecological damage and decreasing soil fertility in Ren’Ai Township of Nantou Country, the Seediq people of Alang Tongan have fallen into a negative cycle that threatens their livelihoods (Figure 4).

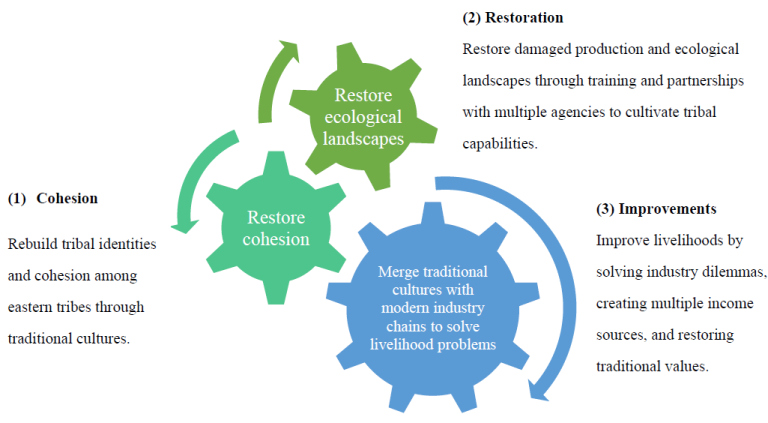

To break out of this negative cycle and restore Gaya, their ancestral code for living sustainably in harmony with the earth, the village of Alang Tongan proposed a vision that is based on “Life, Ecology, and Production”; this vision was promoted on the basis of three pillars, namely cultural revitalization, organic farming, and butterfly ecology (Liu, 2016).

In step one, traditional culture and wisdom are applied to revitalize the tribe and its community-based jobs to regain tribal cohesion and inspire the young members of the tribe to return. In step two, the tribe partners with public agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and schools to restore ecological landscapes through habitat creation and ecological surveys; the objectives are to rebuild traditional homes and set up tribal learning bases for fostering tribal capabilities and reclaim abandoned land. In step three, the restored biodiversity is used to build an ecological habitat park and set up environmental education classrooms that introduce Gaya into the community and industrial developments to improve the livelihoods and well-being of the tribe (Figure 5).

Alang Tongan implemented social development by applying an asset-based model, which involves transforming the tribe into a learning tribe and rediscovering its tribal beliefs and their Gaya. Gaya embodies the essence of harmony and sustainability between humans and nature, and it is particularly relevant in contemporary river basin governance (Chen, 2019). The recent Satoyama Initiative advocates the conservation of socioecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLSs); its vision—the harmonious coexistence of humans and nature—is realized by ensuring the establishment of diverse ecosystem services and values, integrating traditional knowledge with modern technologies, and developing new synergistic management systems (Cheng, 2016). The goal in Taiwan is to leverage Seediq culture as a basis for developing local knowledge of the relationship between humans and nature and for facilitating integrations with modern technology to improve the resilience of the Alang Tongan tribe and ensure the continuance and preservation of their culture. Another outcome is the restoration of Alang Tongan community’s socioecological production landscapes and ecosystems.

Objectives

The objectives of this project are to establish a sustainable tribe that coexists harmoniously with nature; facilitate the restoration of Gaya in Seediq culture and apply its spirit of sustainability in the restoration of SEPLSs and reintegration of industries; and solve problems involving damaged landscapes, non-indigenous land use, the indigenous exodus, and the loss of culture. The tangible objectives are as follows:

- Rediscover traditional Seediq culture and a cohesive, tribal consciousness.

- Restore damaged natural and ecological landscapes and biodiversity.

- Improve industrial and tribal land use while upholding the spirit of coexistence with nature and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal 15 (Scholes et al., 2018).

- Improve tribal livelihoods to ensure that all members of the tribe—young and old, farmers and landowners—receive equitable assistance.

- Develop multiple income sources by leveraging tribal ecologies and indigenous cultures in accordance with Aichi Target 14 (Lin, 2016).

Activities and practices

1. Learning from village elders and rediscovering Seediq traditions

The old villages that the Seediq people once inhabited were lost to the woods during the Japanese rule of Taiwan, and what were once traditional villages have become modernized communities; traditional slate houses are now built with concrete or corrugated iron, and traditional techniques are on the verge of becoming extinct. The Alang Tongan Industry Promotion and Development Association spent numerous years visiting tribal elders to learn and record traditional hunting, weaving, and farming customs as part of an active effort to rediscover the tribe’s Gaya—a code of ethics and conduct—and to encourage the young members of the tribe to return home and inherit their ancestral culture.

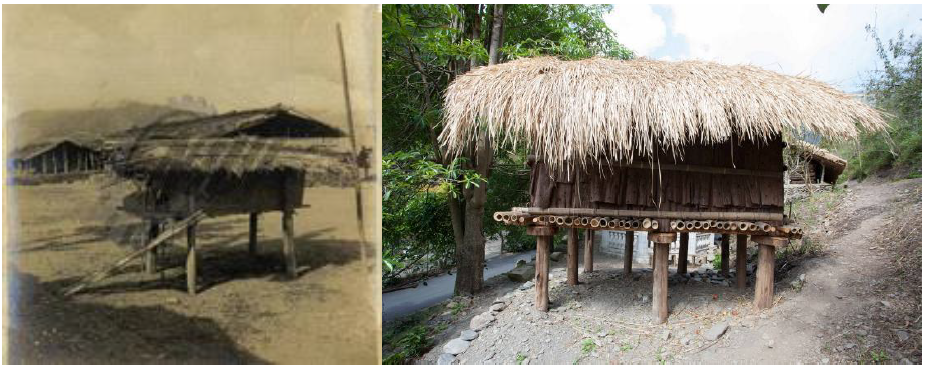

a. Assembling the village to build traditional Seediq homes that were once lost:

In a search for their lost housing culture, the Alang Tongan Industry Promotion and Development Association spent three years conducting field investigations, researching literature from the period of Japanese rule of Taiwan (Chien et al., 2003), collecting and restoring old photographs (Hu, 2003), and interviewing tribal elders to reconstruct the traditional Seediq home culture and traditional Seediq settlement architecture that is recognized by all three Seediq subgroups. Tribal members were invited to form a traditional housing construction crew, and tribal elders with knowledge about the construction of traditional Seediq houses were asked to provide on-site guidance and to pass on their skills to others (Figures 6 and 7). The experience accumulated through this project became part of the tribe’s heritage, including collecting traditional plant materials (e.g., cogon grass and rattan) and learning construction methods. Blessing ceremonies conducted in the Seediq tradition were held before and after the construction process, and tribe members were invited to participate in the events.

The collaboration of tribal members changed the opinions of members who initially opposed the project. Tribal elders who initially refused to pass on their skills also began to help, and the houses were successfully completed. The process also resulted in the successful training of an expert construction team (Figure 8), who passed on their skills to other Seediq tribes and helped them to rebuild their ancestral homes. The Seediq people’s culture pertaining to their family homes is deeply tied to the concept of Utux, that is, their belief in ancestral spirits. By restoring the Seediq culture of family homes, the spirit of Utux was also restored (Chen, 2019). This belief not only determines the interactions between humans and the land but also leads to the creation of a set of ethics and rules, that is, Gaya.

b. Reviving Smratuc after 80 years

Smratuc is the Gaya (ritual) that is held before the tribe plants its millet. This ritual comprises two parts: the new year’s ceremony Cmucut and the sowing ceremony Tmukuy macu. Smratuc is a hereditary ritual, but during the Japanese rule of Taiwan, the Seediq people were forced to relocate to the plains, and this Gaya ceased to be practiced by the Seediq. Only a few village elders who had participated in the Gaya as children retained vague impressions of the ritual; most of the other members of the tribe did not know the meaning or significance of this Gaya.

Gaya’s resurrection requires returning its rituals; only then can its ideas be continued. With assistance from community development associations, tribal councils, the Nanfeng Village Office, the Taiwan Indigenous Tribe Culture and Education Revitalization Foundation, and the civic-minded members of the tribe, Alang Tongan held a Smratuc again for the first time in 80 years in 2011 (Figure 9); the event was held to inspire the Seediq people to continue their traditions and rituals and restore the Gaya in their tribe (Iwam Perin, 2011).

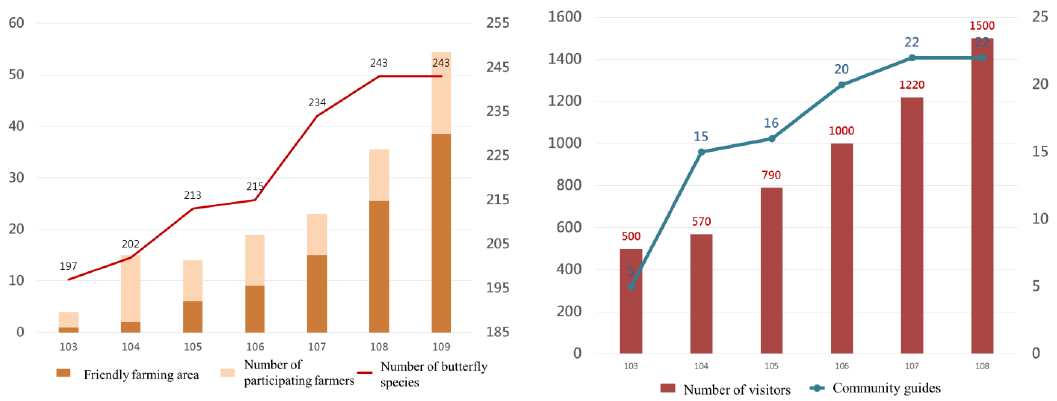

2. Raising tribal capabilities through classes and training

The Nanshan River Basin in Nanfeng Village is known for its abundant butterfly resources. This region was previously devastated by overhunting, habitat destruction, and natural disasters such as earthquakes and typhoons. As part of efforts to restore the natural ecology of the basin (Chiu & Peng, 2014), in 2012, the ESRI, National Chi Nan University, the SWCB, and other relevant agencies collaborated with tribes to identify butterfly resources, plan surveys of butterfly habitats, care for Nanshan River ecologies, and maintain butterfly environments. Their goal was to establish a culture of respect for nature and promote knowledge about the relationship between humans and nature as a foundation for the subsequent training of tribal and ecological guides (Figure 10). This requires learning about the Seediq people’s traditional ecological knowledge to connect traditional crops with butterfly host plants and applying that knowledge to ecological tour guide systems (Liu, 2016). By guiding tribal residents to integrate ecotourism in tribal construction and SWCB rural revitalization programs, SEPLS concepts may be applied to ensure the diversity of ecosystem services and values and the sustainable conservation of butterfly resources. The aforementioned measures provide a means of restoring the butterfly-catching industry of the past.

In 2019, the Satoyama Initiative was introduced to Alang Tongan. A SEPLS resiliency assessment (Figure 11) was used to review the tribe revitalization measures and changes. The results of the assessment revealed to the tribal residents that although years of training and counseling have helped the tribe to regain concepts about ecological coexistence, their livelihoods and well-being were still inadequate, resulting in population loss; in turn, this problem led to the loss of traditions and culture and the weakening the tribe. After a SEPLS analysis and discussions were conducted, tribal partners expressed their wish to restore traditional Seediq industrial models involving mutual aid and benefits and to leverage these models to set up tribal industrial chains that help tribal farmers and promote cultural heritage. The underlying objective is the practice of Gaya—sustained harmony between humans and nature—in the livelihoods of the tribe.

3. Restoring the traditional mechanism of consensus decision-making to increase tribal engagement and cohesion

In Seediq society, a community is formed when groups (families) comprising different functions follow the customs and rules of Gaya and work together to maintain their tribe as a collective (Sun, 2010). The Seediq people do not have village chiefs; instead, family elders are the decision-makers, and the elders of every family meet to discuss and decide on every major decision. In the current representative system, the roles of traditional tribal leaders have gradually been replaced with those of village leaders and local representatives.

Alang Tongan partnered with National Chi Nan University to implement a participatory budgeting program introducing the Seediq consensus decision-making system and incorporatesing tribal elder roles into current civic deliberation mechanisms. First, a three-way discussion between the tribes, National Chi Nan University, and the Ren’ai Township was conducted; subsequently, local chiefs, church leaders, and tribal elders were invited to attend a focus discussion in Alang Tongan to learn about traditional tribal adjudication norms and to set up civic deliberation mechanisms together.

Alang Tongan comprises three main communities (Figure 12). The tribal engagement was expanded through visits to paramount tribal organizations, multiple briefing sessions, and tribal bulletins—everyone was able to express their opinions and raise proposals, and all tribal members could vote on the future direction of their tribe (Figure 13). The creation of a platform that gave a voice to all members of the tribe and allowed them to participate in decision-making processes represented a return to the Seediq tradition of consensus decision-making, which allowed the tribe members to understand the actual needs of their tribe. This platform also increases elder engagement in community promotion projects; therefore, it indirectly accomplishes elder care and local revitalization objectives.

4. Partnering with public departments to restore landscapes damaged by natural disasters

An upstream collapse during Typhoon Mindulle, which occurred in 2003, caused a severe damming of the river and accumulateed rocks and stones at the base of the river. Typhoon Sinlaku and Typhoon Morakot, which occurred in 2008 and 2009, respectively, further contributed to the low use levels over the years and considerably reduced the number of life forms found in the area. For example, Japan’s Futaba District, which had experienced tsunamis, earthquakes and the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Incident, urgently requires social—in addition to ecological—restoration and hopes to increase its postdisaster resilience through reconstruction and greening projects. Mabon (2019) asserted that in disaster recovery plans, cultural ecosystem services associated with landscape features could enhance civilian well-being and serve as educational spaces, increasing the preparedness of a community against future disasters; ecosystem services may also serve as symbols of a community’s revival by rebuilding its pride and reviving its local identity. Tidball (2014) and Tidball and Atkipis (2018) also emphasized that postdisaster greening allows communities to reinforce their connections with each other and their ability to organize themselves.

To restore the rich ecosystems of Alang Tongan’s past, community residents were persuaded to release their private lands and initiate a Noah’s Ark project in conjunction with the disaster prevention and management efforts of the SWCB. Tribal members proposed replacing conventional concrete structures with ecological habitats featuring flood detention functions; they planned the construction of seven manmade pools—some were shallow, some were deep, and some had wetlands and waterways—next to the river Bakei. The villages planted nectariferous plants and created ecological water habitats (Figure 14) to recreate original ecosystems and restore natural environments. These habitats not only adhere to the Seediq Gaya regarding the pulse of nature but also demonstrate the integration of traditional knowledge and modern technology in SEPLSs to reduce floods.

While creating these habitats, the tribal construction crew partnered with government departments to integrate traditional construction techniques into its construction process. Tribal elders guided youths in building traditional homes, barns, and bamboo bridges (Figure 15) as the major features of the habitats. Paddy terraces were also rebuilt and converted into shared farming zones that the tribe can use.

- 5. Restoring traditional Seediq culture and ecological diversity

Gaya calls for the moderate use of resources during interactions between the Seediq people and nature. The land is let lie fallow after four to five years of farming and recultivated in accordance with a plan. After a series of capability improvements and awareness campaigns, the residents of Alang Tongan began to reflect on the competitive relationship between tribal industries and the ecological landscape. They then implemented the recultivation and conservation of traditional crops on the basis of four main axes (i.e., edible landscapes [daily living], the craft industry [handicrafts], landscape plants [ecological restoration], and food crops [industry]) as a part of a cultural and ecological restoration program. This program involved planting, conserving, and cultivating craft materials, unique vegetables, medicinal herbs, and landscape vegetation to restore traditional and ecological Seediq landscapes and increase the biodiversity of the area.

6. Promoting friendly agricultural practices that embody tradition and coexistence with nature

With the rise of Taiwan’s industries, its agriculture has declined, resulting in the departure of youths from agricultural villages. This reduction in agricultural labor has led to the abandonment of farmlands or the leasing of these farmlands to non-tribe entities. The perception that people are farming their lands for other people’s gain has eroded the relationship between residents and their land and destroyed natural ecologies (Kuan, 2014). To massively increase agricultural production, farmers developed the mountains by building greenhouses and adopting unsustainable agricultural practices involving the use of large machinery and chemical fertilizers that damaged soil productivity; consequently, soil health decreased every year. The 1999 earthquake and typhoon-induced flooding resulted in avalanches and landslides, and farming ecologies were subsequently affected by a negative cycle. Land disputes, land use conflicts, and trade-offs between human needs and agricultural landscape functions are now the major problems in landscape ecology (García-Martín et al., 2020).

Faced with the stagnation of native tribal agriculture, the tribe decided to transform their agricultural practices in accordance with Gaya. This transformation involved the planning of agricultural techniques, approaches, and management in the spirit of the common good; the measures implemented are as follows:

a. Agricultural production techniques and management models that align with tribal agricultural development were developed to reestablish indigenous economic models and lifestyles on the basis of mutual assistance, maintain local ecological environments, and promote sustainable land development.

b. Intermediary groups and organizations that assist with tribal agricultural development were established to support farmers in the development of cooperative production and sales, provide professional operational and management support, and promote the adoption of a social enterprise business model in tribal agriculture.

c. Native farmers were encouraged to modernize by undergoing training courses on natural agricultural practices and production and marketing techniques to build up a native reserve of human capital and resources for natural farming.

7. Establishing symbiotic tribal industry chains and assisting tribal farmers

Years of tribal development have led to insights into the problems encountered by the tribe, that is, low crop prices, unusable land, insufficient labor, land abandonment, and a lack of sales channels for marketable goods; notably, these problems are intricately linked to each other. The Alang Tongan Industry Promotion and Development Association subsequently promoted the development of a symbiotic community and industry platform that is based on the Seediq traditions of shared farming and shared rewards.

The concept of a credit union was introduced into Taiwan by the Catholic Church in 1964. A credit union is funded by the money regularly deposited by its members, who may take out loans from it. In the past, the indigenous people of Alang Tongan had limited incomes, and the local Catholic church set up the Meixi Credit Union, which upholds the spirit of mutual assistance and self-help. When its members require help, the credit union can provide timely financial assistance; this includes student loans (for the children in the tribe), living allowances, and small loans (Fan, 2015). To date, the credit union has loaned a cumulative total of NTD 300 million.

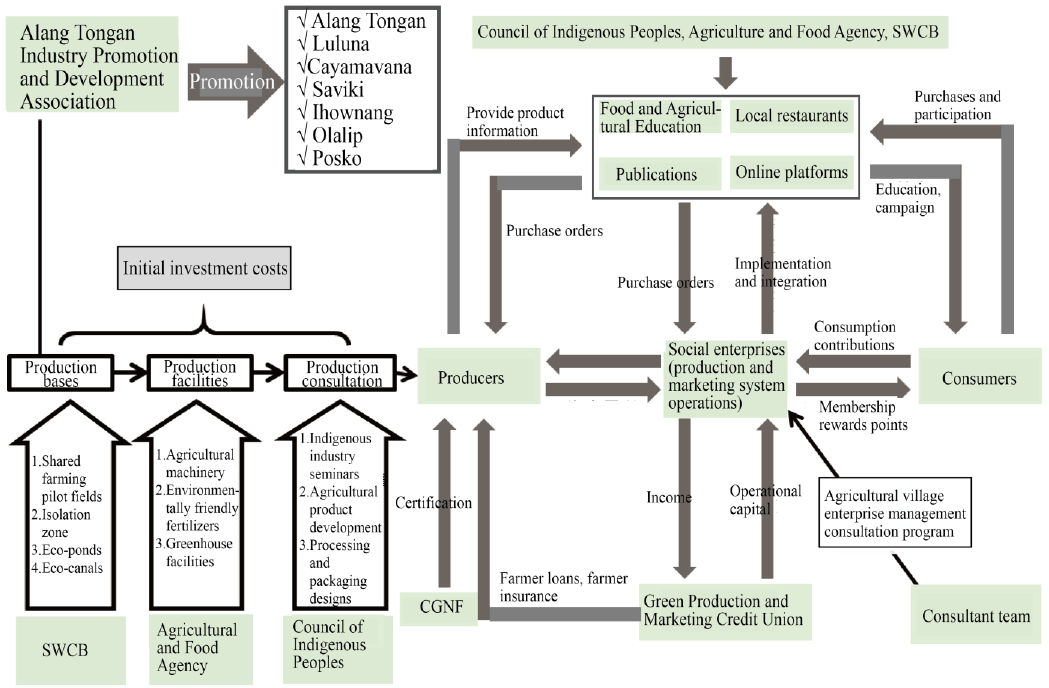

A platform for integrating management concepts into tribal industry chains (Figure 16) was initiated by the Alang Tongan Industry Promotion and Development Association to promote the development of seven tribes from the counties of Nantou (Alang Tongan, Luluna), Chiayi (Cayamavana, Saviki), and Hualian (Ihownang, Olalip, and Posko). The SWCB, the Agriculture and Food Agency, and the Council of Indigenous Peoples covered the initial production costs and provided the initial production resources; they also searched for local Cho-Global-Natural-Farming-certified producers or farmers’ associations that sold products to consumers through social enterprises, which served as operating bases for their production and sales systems. A green production and sales credit union can maintain its operations through social enterprises and the provision of mutual financial assistance to local farmers. Furthermore, the three authorities mentioned above can share information about farmers through various means (e.g., food and agricultural education activities, local restaurants, publications, and online platforms) and use various channels to encourage consumers to purchase organic produce.

On the basis of a credit union model, Alang Tongan established a circular cooperative economic model comprising local farmers’ associations (Figure 16). This platform provides comprehensive and holistic assistance from planting, consultations, training, and processing to marketing, operations, and sales. The purpose of the platform is to guarantee incomes, provide job opportunities to retain young talent and establish community farming teams to assist farmers who cannot farm their fields.

The plant cultivation team and the self-circulating mechanism provide comprehensive and holistic assistance—from planting, techniques, and processing to marketing, operations, and sales. They focus not on achieving a high level of professionalism but on improving existing foundations to develop additional incomes. Older farmers who cannot farm their fields because of mobility issues or have abandoned or leased out their land can gain an income stream while providing their land for use by the platform; the platform then commissions plant cultivation teams to manage the fields of these older farmers in the tradition of Mssbarux—payment through labor—to achieve a partnership that is based on mutual assistance (Figure 17). The subsequent processing and sales can also be handled by the platform as part of a one-stop operational model that slowly creates community employment opportunities. This operating model helps farmers to overcome poverty and facilitates the implementation of a household production model that encourages young generations to return to the tribe for employment while applying Gaya to land use to allow the land to heal and recover; the model also reduces the leasing of farmlands to non-tribe entities and environmental uncertainties (Wang, 2014).

8. Reviving and integrating indigenous cultural heritage with ecological restoration to develop diversified incomes

Through the accumulation of in-depth experience based on Seediq traditions and culture, Seediq culture evolved from a state of abandonment to a rare feature that can be displayed to outsiders. The tribes can rebuild their culture and confidence while connecting with local ecologies and developing cultural and ecological tourism to attract travelers to Alang Tongan and increase their incomes.

Outcomes

With traditional Seediq culture as the core target, the members of Alang Tongan substantially enhanced their knowledge, skills, and capabilities through self-developed educational programs and the guidance provided by partner agencies. These enhancements allowed them to rediscover their connection with the land in terms of production, lifestyle, and ecology, leading to the revitalization of their tribe and the restoration of SEPLSs. The outcomes of the restoration and revitalization programs are as follows:

1. Restoring and converting abandoned community land into ecological, production, and living landscapes

After convincing tribal residents to release their private land, Alang Tongan partnered with the SWCB to convert 0.8 ha of abandoned farmland into an ecological park in conjunction with the implementation of student commute projects (Figure 18). The park was constructed using Seediq construction techniques, and nectariferous plants were grown in the park to create ecological water habitats and increase local biodiversity. Original farmlands were also restored as the shared farmlands of the tribe and used to plant traditional spices and specialty crops.

The Seediq cultural and ecological education park provides safe roads that children in the tribe can use to travel to and from school; the park also serves as a venue for conducting Seediq cultural and ecological environmental education (Figure 19), which is integrated into the indigenous cultural heritage courses taught at Nanfeng Elementary School (Figure 20).In conjunction with establishing the park, the community also developed ecological experience itineraries (e.g., butterfly tours, cultural tours, and hunting and cultural experiences) to increase the income diversity of the tribe. The shared farmlands and nurseries are used by the tribe’s production and marketing classes to cultivate seedlings and hold friendly agricultural training courses, all of which benefit community industries.

Figure 19. Various uses of Seediq Cultural and Ecological Park

2. Establishing a community-friendly industry system for the common good and increasing environmentally friendly planting areas

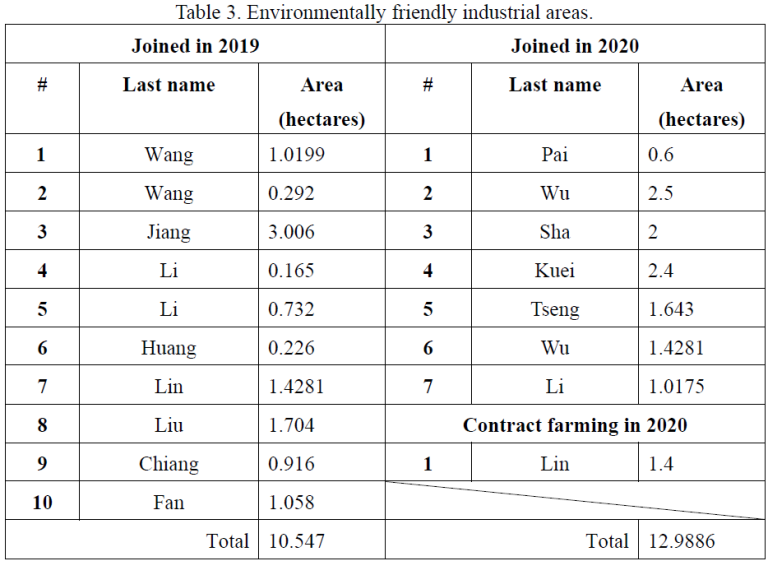

The tribal special crop production and sales class were established in 2019 to promote the adoption of a circular cooperative and economic model by local farmers’ associations. The model involves providing seedlings, technical guidance, personnel training, and contract farming partnerships to association members. Farmers are encouraged to convert to environmentally friendly agricultural practices while learning environmentally friendly agricultural techniques and improving the value of their crops. At present, 16 farmers from the tribe have participated in this program and increased their environmentally friendly planting area by 23.54 ha; these farmers have also agreed to provide 10 ha of land to a production and sales contract farming team (Table 3). The program has also helped six tribes in three municipalities (Figure 21) to form a partnership to create mechanisms that generate common benefits for indigenous tribal industries.

※ Cooperating indigenous tribes

➢ The Luluna tribe in Nantou

➢ The Cayamavana tribe in Chiayi

➢ The Saviki tribe in Chiayi

➢ The Ihownang tribe in Hualian

➢ The Olalip tribe in Hualian

➢ The Posko tribe in Hualian

3. Increasing agricultural income

Kim, Kang, Park, and Lee (2018) argued that agricultural intensification is a factor that contributes to human-induced landscape degradation; it reduces soil fertility and biodiversity while increasing groundwater pollution and greenhouse gas emissions (Andela et al., 2017). By contrast, traditional agroecological practices that are adapted to a specific area provide various cultural and ecological benefits, such as traditional ecological knowledge, biodiversity conservation, crop diversity, soil augmentation, air and water quality improvements, and support for sociocultural structures (Lomba et al., 2015).

On the basis of traditional Seediq culture and ecological conservation, Alang Tongan selected oil-seed camellia production, which involves the cultivation of traditional and special indigenous crops, as a focus of its industrial development. Organic oil-seed camellia plants were planted in restored tribal land and supplied to the production and sales class, who then established standardized production procedures for the cultivation of oil-seed camellia. The class also promoted the concept of quality certification to build up the tribe’s industrial brand image and value and to enhance its brand positioning and consumer recognition.

The production and sales class managed cost subscription and purchasing, processing, and sales on community platforms. Platform profits were transferred back to the community and farmers pro rata and invested in the subsequent harvest. The sale of oil-seed camellia seedlings in 2020 generated approximately NTD 600,000 in profits, and the camellia oil produced by the tribe was awarded multiple Michelin stars for its quality (Figure 22)

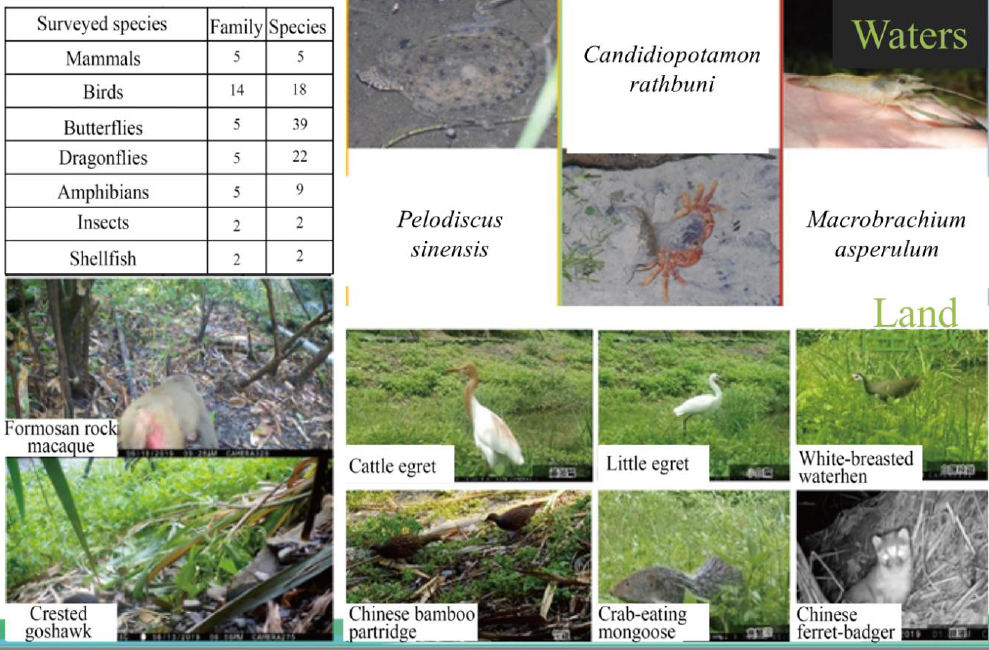

4. Restoring biodiversity

According to Ohwaki, Ogawa, Taketani, and Tomisawa (2014), several species of butterflies respond positively to abandoned farmlands. Thus, abandoned farmlands can mitigate the harmful effects of landscape simplification and severe human disturbances. After numerous years of hard work by participating agencies and its residents, Alang Tongan successfully restored approximately 1.6 ha of its damaged land and ecological landscapes, transforming them into natural and ecological landscapes (Figure 23). Butterfly catching also evolved from using butterfly nets to using cameras and camera phones to photograph them. After the construction of ecological ponds was completed, approximately 107 plant species were planted within the corridor. The walking paths that extend from the green farms were home to 70 butterfly species before the restoration; currently, 243 species from five families can be seen in Alang Tongan. The restoration of Alang Tongan’s butterfly kingdom to its past glory is also evidence of habitat and ecosystem recovery, and numerous other animal species have returned to the area (Figure 24).

5. Increasing incomes using biodiversity

The recovery of ecological industry chains has led to new economic development (Figure 25). To establish Taiwan’s only butterfly conservation green tour and address tribal development challenges and marketing goals, Alang Tongan was developed to allow tourists to experience green environments (the mountains and rivers), green ecologies (butterfly ecology), green agriculture (organic production), green itineraries (smokeless industries), green culture (Seediq culture), and green talent (tribal cultures and arts). A benefit of these green tours is that tourists leave minimal carbon footprints, especially in the major centers for butterfly photography, butterfly conservation, and butterfly research.

The cultural and ecological successes in Alang Tongan have attracted tribal youths to return home for employment and created secondary employment opportunities for tribal residents. An example is Pawan Neyung, who moved away at the age of 18 and worked as an actor and mountain guide; he returned to the community to learn traditional bow-making and hunting from his father and opened a series of guided courses that allow tourists to experience the traditional hunting culture of the Seediq people. In 2018, the Sun Moon Lake National Scenic Area Administration and the SWCB co-organized a butterfly tour campaign that was held from April to June to promote the natural scenery of Alang Tongan and the Seediq people’s local knowledge and understanding of butterflies. This campaign highlighted the unique status of Alang Tongan as a basis for traditional tribal tours.

Lessons learned

A. Respecting local traditions and culture and integrating them into revitalization efforts

The key to the success of the Satoyama Initiative in Alang Tongan lies in its local traditional and cultural heritages. The three-fold approach to implementing the Satoyama Initiative involves recognizing the value and crucial role of local traditions and cultures and respecting them during the integration of various innovative concepts. This strategy was applied in SEPLS restoration in accordance with the traditions and customs of Gaya; consequently, the changes implemented were positively received by the locals, which reinforced local cohesion and momentum.

B. Cultivating concepts and change among locals as key to revitalization

Improving the awareness and sensitivity of residents regarding their environment, environmental concepts and knowledge, environmental values and attitudes, environmental actions skills, and environmental action experiences is the key to driving transformation (Chiu & Peng, 2017). Ecological researchers have verified through numerous years of theoretical and practical environmental education research that changes from the bottom-up are the first step to achieving sustainable changes. Changes from the bottom-up also echo the three-fold approach in the Satoyama Initiative, which calls for managing natural resources through the participation of all parties and partners.

C. Leveraging regional advantages as part of an overall plan for revitalization

To implement landscape management that promotes the Satoyama Initiative socially, ecologically, and productively, a comprehensive assessment plan is required. The inherent conditions and cultural features of indigenous tribes provide them with advantages in developing ecotourism, conserving biodiversity, and implementing the Satoyama Initiative; however, agricultural villages must still overcome problems such as population aging, cultural loss, industrial difficulties, and environmental damage. Maintaining the balance between industrial development and ecological sustainability requires the formulation of a comprehensive community-building plan in conjunction with synchronous improvements in cultural restoration, local care, industrial guidance, and environmental construction. In addition to restoring resilience in lifestyles, production, and ecologies, this strategy also creates a stable foundation for attaining sustainable development and the Satoyama vision.

D. Key role of collaborative partnerships in promoting community and SEPLS revitalization

Over the years, the community has integrated locals, NGOs, academic entities, government agencies, and other resources; for example, it integrated resources through community production and sales classes to encourage residents to reclaim the land that they had leased out. The community also sought aid from the SWCB to restore ecological habitats and create green corridors on the basis of ecological, economic, and living needs. The community also partnered with academic and research institutions (National Chi Nan University and National Formosa University) to acquire the knowledge required to improve the capabilities of locals and achieve SEPLS revitalization.

E. Indigenous positioning within Gaya and capitalism-based changes

The loss of traditional cultures and the rise of capitalism have altered the traditional socioeconomic models of the Tgdaya people. Tribal residents lost sight of the balance they originally maintained between self-sufficiency and adequacy and gradually abandoned their commitment to their traditional customs in the face of poverty. After experiencing this decline for a longtime and identifying solution aligned with the Gaya spirit of promoting the common good, the community introduced a communal farming system to restore the Tgdaya socioeconomic model; that is, they introduced a community-supported agricultural and management model. The concept of shared harvests corresponds to the spirit of sharing that is present within indigenous cultures. In the future, the goal is to develop B-type social enterprises to seamlessly integrate traditional cultures and creative concepts and pave the way for the development of indigenous industries.

Key messages

- Focus on recovery first before proceeding with improvements.

- Respect and learn from the traditional wisdom of agricultural villages and indigenous tribes; their traditions and customs may guide us to the optimal solutions.

- Ensure that everyone’s needs are met such that they can focus on other tasks; the first step is to overcome tribal poverty—when everyone benefits, the community benefits.

- Explore new shared management systems or evolving structures of shared wealth; this is an essential process.

Funding

This present research received funding from the SWCB Satoyama-Initiative-in-Taiwan Project.

References

Scholes, R., L. Montanarella, A. Brainich, N. Barger, B. ten Brink, M. Cantele, B. Erasmus, J. Fisher, T. Gardner, T. G. Holland, F. Kohler, J. S. Kotiaho, G. Von Maltitz, G. Nangendo, R. Pandit, J. Parrotta, M. D. Potts, S. Prince, M. Sankaran and L. Willemen (eds.). (2018). Summary forpolicymakers of the assessment report on land degradation and restoration of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

Kim, G. W., Kang, W., Park, C. R. and Lee, D. (2018). Factors of spatial distribution of Korean village groves and relevance to landscape conservation. Landscape and Urban Planning 176: 30-37.

Andela, N., D. C. Morton, L. Giglio, Y. Chen, G. R. van der Werf, P. S. Kasibhatla, … and Randerson, J. T. (2017). A human-driven decline in global burned area. Science 356 (6345): 1356-1362.

Lomba, A., P. Alves, R. H. Jongman and D. I. McCracken. (2015) Reconciling nature conservationand traditional farming practices: A spatially explicit framework to assess the extent of High Nature Value farmlands in the European countryside. Ecology and Evolution 5(5): 1031-1044.

Ohwaki, A., H. Ogawa, K. Taketani and A. Tomisawa. (2014). Butterfly responses to cultivated field abandonment are related with ecological traits in a temperate Japanese agricultural landscape. Landscape and Urban Planning 125: 174-182.

García-Martín, M., Torralba, M., Quintas-Soriano, C., Kahl, J. and Plieninger, T. (2021). Linking food systems and landscape sustainability in the Mediterranean region. Landscape Ecology. 36: 2259–2275.

Mabon, L. (2019). Enhancing post-disaster resilience by ‘building back greener’: Evaluating the contribution of nature-based solutions to recovery planning in Futaba County, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. Landscape and Urban Planning 187: 105-118.

Tidball, K. (2014). Seeing the forest for the trees hybridity and social-ecological symbols, rituals and resilience in post-disaster contexts. Ecology and Society 19(4): 25.

Tidball, K. and A. Atkipis. (2018). Feedback enhances greening during disaster recovery: A model of social and ecological processes in neighborhood scale investment. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 34: 269-280.

Li, Y.-Y. (1983). The Study and Evaluation Report of Highland Administrative Policy. Taipei: Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica.

Hu, T.-L. (2003). Culture Performance and Taiwan’s Aboriginal. Taipei: Linking Publishing Company.

Sun, D.-C. (2010). Ethnic Construction in the cracks: Taiwan’s Aboriginal Languages, Culture and Politics. Taipei: UNITAS Publishing Co.

Chiu, M.-L. and Peng, K.-D. (2014). Field Guide for Butterfly Environmental Education. Nantou: Endemic Species Research Institute, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan.

Chiu, M.-L. and Peng, K.-D. (2017). The role of scientist in the practice of Satoyama Initiative in local community – the experience and review in Nanfong community. Nature Conservation Quarterly 98: 4-19.

Kuan, D.-W. (2014). Challenges for the Realization of Indigenous Land Rights in Contemporary Taiwan: A Regional Study of Indigenous Reserved Land Trade between Indigenous and Non-indigenous People. Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology 80: 7-51.

Wang, M.-H. (2014). Exploring the Transformation of Capitalism from Perspectives of Waya: Economic Changes in a Sediq Community. Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology 80:53-102.

Chien, H. M. (2003). The Oral History and Culture of Alang Tongan. Taipei: Council for Cultural Affairs, Executive Yuan.

Iwan-P. L. (2011). One of the Action Bases- Alang Tongan. Taichung.

Fan, H.-Y. (2015). Indigenous Bank- A Case of Alang Tongan Savings & Credit Cooperative, Nantou County, Taiwan. Journal of The Taiwan Indigenous Studies Association 5(2): 97-113.

Chen, C.-L. (2019). Indigenous Traditional Knowledge and Watershed Governance – The Attempt on Alang Tongan. The Column of Alang Tongan: Groping, Growth and Transformation. Nantou: Shui Sha Lian Research Center for Humanities Innovation and Social Practice, National Chi Nan University 31:11-16.

Liu, M.-H. (2016). Faded Color Wings: Oral History of Catching Butterflies in Alang Tongan/Baike. Journal of the Taiwan Indigenous Studies Association 6(1): 73-96.

Cheng, I -C. (2016). A Preliminary Study on the Indigenous Practice the Spirit of Satoyama Initiative. Agriculture Policy & Review.

Lin, D.-L. (2016). The Aichi Biodiversity Targets and Biodiversity Indicators. Nature Conservation Quarterly.