SDM Project: Vetiver Grass Technology Plays A Crucial Role In Lake Victoria Ecosystem Restoration

01.02.2023

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION

Environmental Protection Information Centre (EPIC)

DATE OF SUBMISSION

05/02/2022

REGION

Africa

COUNTRY

Uganda

LOCATION

Lake Victoria in Buikwe, Manafa and Jinja Districts

KEYWORDS

Ecosystem Restoration, Lake Victoria, Eutrophication

AUTHOR(S)

Imran Ahimbisibwe

Abstract

Eutrophication in Lake Victoria is associated with the growth and spread of water hyacinth weed (eichhornia crassipes). This case study describes Lake Victoria ecosystem restoration work undertaken by Environmental Protection Information Centre (EPIC), in conjunction with her partners and lakeside communities. The project was designed mainly to address Eutrophication, at the same time to reverse land degradation in the surrounding watersheds through climate change resilience enhancement and boost food security.

The paper highlights achievements of the initiative, which include public awareness raising, establishment of Vetiver grass nursery for the community and application of nature based Vetiver Grass Technology (VGT) on farmers’ crop fields. At Wanyange landing site which had the worst invasion of Water Hyacinth and where VGT is in application, Vetiver grass barriers utterly blocked the flow of runoff carrying nutrients, sediment and pollution to the lake. As a result, water hyacinth weed was starved and retreated from the shoreline.

The report expounds opportunities that exist in ecosystem restoration and states challenges that undermine restoration activities.

It indicates information derived from culture and traditional knowledge that supports restoration work. Several focus group discussions (FGD) and key informant interviews were conducted to obtain information on traditional and current resource management practices and to gain first-hand information on ecosystem restoration initiatives by various stakeholders.

It can be inferred therefore that SEPLS concept is the ideal management approach for Lake Victoria ecosystem restoration because it embraces interlia the social and ecological aspects of the problems which were overlooked by previous managers.

1. Background information

Lake Victoria basin has a population of 40 million with a population density of 250 per square kilometre (African Great Lakes International Conference 2017). The lake is the second largest freshwater body in the world and the largest tropical lake. It straddles across the boundaries of Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. It has a surface area of 68,000 km squared. Its shoreline stretches 3,440 km and has a catchment area of 193,000 km squared. Lake Victoria is a shallow lake with its deepest point averaging 100 meters. Policy formulation and management of the lake resource are responsibilities of Lake Victoria Basin Commission. A common management structure known as Beach Management Units (BMU) that exists on all landing sites in the three riparian states oversees the day to day running of the fishery. Headed by an elected local leader BMUs set and enforce rules and standards of the fishing community. However foreign processing plants and cage fish farms operate outside the scope of BMUs according to respondents of the baseline survey carried out by EPIC.

Lake Victoria ecosystem is suffering from two main ecological drawbacks namely introductions in the lake of invasive alien species such as the predator Nile perch (lates niloticus) and colonisation by invasive Water Hyacinth weed (Eichhornia crassipes). The two ills have combined to cause malfunctioning of ecosystem’s provisioning and regulating services thus undermining human wellbeing and ecosystem health. Healthy ecosystems determine the viability of economic activities and sustainability of livelihoods in any ecosystem. For instance seasonal extreme weather events in form of hurricanes, which are caused by anthropogenic carbon emissions induced global warming, devastate infrastructure and assets in USA economy thus portraying interdependency between sound ecosystems and economic feasibility. The urgent need of restoration of Lake Victoria ecosystem therefore stems not only from the loss of 500 or so native fish species of Haplochromines that were decimated by introduction of exotic predator Nile perch, but also is justified by the fact that 40 million people depend on the ecosystem for food, livelihoods and other services. The lake also influences rain partners in this semiarid poor region that thrives on rain fed agriculture. It is therefore imperative to repair the damage inflicted on Lake Victoria Ecosystem taking advantage of on-going efforts by United Nation’s decade of ecosystems restoration. Moreover the decision to trade biological diversity for sufficient but unsustainable fish exports is a management defect. It can be addressed effectively by the new SEPLS management system that encompasses all aspects in the socio-economic, ecological and production domains. The following section examines values of different stakeholders and their impact on Lake Victoria ecosystem.

1.1 Multi stakeholder values

Whereas the notion of multi stakeholder values is ideally representative of social inclusiveness and a desired element of SEPLS concept, however on close examination certain values are negative and contradictory to sustainable use of resources. For example, management of LVB is confronted by pressure from international development agencies’ inclination to develop further Nile perch fishery purportedly to support economic development in the region in spite of its negative impacts on social and ecological aspects. On the other hand, environmentalists and Indigenous Local People share views on the values of biodiversity conservation and particularly diversity of native fish species. They perceive the Nile perch fishery as a tragedy of the commons that altered the balance of ecosystem goods and services, and redistributed benefits flowing from them. Economic benefits from the liberalised Nile perch fishery flow almost exclusively to foreign companies which can afford capital intensive investments. Biological diversity is traded for significant but unsustainable fish export earnings, they claim.

Jinja is the largest industrial city of Uganda and is located on the shore line of the lake. Virtually all industries claim a share on the lake’s waste repository capacity hence industries discharge untreated effluent in the lake causing serious pollution. Two large scale sugar estates of Madihvan group in Kakira and Uganda Sugar Corporation of Lugazi are located on adjacent watersheds from where residues of fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides flow directly from sugar plantations to pollute the lake. The sugar estates run out-growers scheme which hitherto was supportive of livelihoods of local communities. Nevertheless currently the scheme enhances income generation only for individuals that obtain sugar cane supply contracts from the factory, a category of exclusively rich people who sell at factory price while farmers get much less for their sugar canes. Put it differently, the value chain is now dominated by middle players who take the lion’s share of proceeds. The new order threatens sugar cane production as farmers fail to break even amidst ever increasing input costs. The sugar estates also provide unskilled employment to a large number of both local and immigrant workers in addition to other public facilities such as schools and hospitals.

Other stake holders include urban development projects in form of road construction and housing, financed by both the private and public sectors in pursuit of rapid economic development. Gold mining, sand excavation and rice schemes in Katonga and Lwela wetlands, have negative impacts on Lake Victoria ecosystem irrespective of their contribution to national development. Construction and agriculture involve draining the wetlands and obstructing water channels besides chemical contamination of water. Smallholder agriculture, grazing and collection of raw materials constitute a large per cent of land resource utilization in LVB. National water and Sewerage Corporation use the lake as a source of its water supplies and at the same time it discharges sewerage in adjacent swamps for natural purification before entering the lake.

Tourism is growing very fast around Lake Victoria with more than 170 tourists’ hotels erected on the shoreline in the three riparian states of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. High traffic of tourists exerts pressure on fragile environments. Plastic litter is one cause of environmental degradation in addition to structural changes of the natural scenery to accommodate roads and buildings among other things. Sewerage from the hotels is discharged untreated in the lake. The sewage is a serious threat to tourist beaches and local population, since dirty water can cause infections of the ear, nose, and throat among bathers, not to mention hepatitis, dysentery and enteritis. Although tourism generates substantial foreign currency for local economy, however its negative environmental impact on the lake should not be discounted.

Aquaculture on Lake Victoria is becoming a social and ecological menace. Besides congesting the lake with floating cages made out of plastic materials, boat owners complain that cages block ways used to transport goods and people. Caged fish are fed on artificial feeds whose residues rote in the water thus creating a disgusting foul besides exacerbating eutrophication. Furthermore caged fish are susceptible to infections due to restricted feeding and confinement in an overcrowded place. They infect the natural fish in the water thus posing a threat to the entire fishery in the lake. Spawning which under normal circumstances takes place in a different place from where they feed is also constricted. Ideally healthy fish move freely in search of suitable conditions such as temperatures in the water, oxygen, light and natural food among other things. In the process they exercise their bodies and feed on a variety of natural food in the expanse of the entire lake. It can be deduced therefore that caged fish aquaculture on Lake Victoria is ill conceived and threatens the entire fishery with grim consequences for consumers, investors and biological diversity.

On proposed and existing interventions, EPIC and its partners engaged industries including large scale agriculture enterprises to adopt Vetiver Grass Technology (VGT) for pollution and sediment control; and for climate change resilience enhancement by retention of moisture and soil nutrients in plantations. They responded positively and an initiative by local authorities is in the pipeline to develop a policy to that effect.

Lake Victoria Environment Management Program phases 1 and 2 partly funded by World Bank group supported knowledge building activities and institutional capacity building for managing the lake. Global Environmental Facility (GEF) supports riparian states to address trans-boundary pollution ad management related issues. In the following section the invasion of Water Hyacinth weed is elaborated.

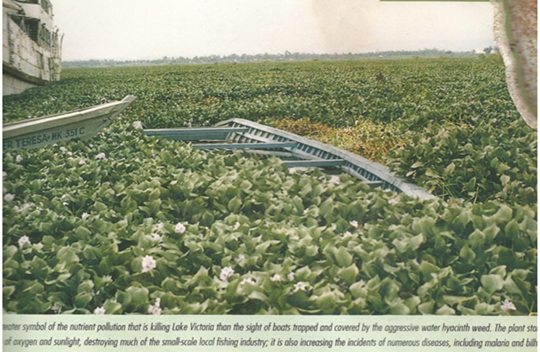

1.2 Invasion of Water Hyacinth Weed

The region around Lake Victoria receives more rainfall throughout the year than other regions in the country. Therefore the incidence of runoff is very high and so is soil erosion in crop fields on adjacent watersheds. LVB ecosystem comprise of several tributary rivers to the Nile basin system, which conduit sediment and pollution, for example, from as far as Rwanda and Burundi through River Kagera. A satellite image shows an area of water in Lake Victoria with a high content of soil particles (the green patch), a cause of pollution. The sedimentation is on mouths of two major rivers-the Miriu Sondu and the Nyando that flow in the lake year round near Kisumu in Kenya. The Miriu Sondu originates in Mau forest, Kenya’s largest remaining forest area perched high on the rift valley escarpment. This forest is under severe threats from overexploitation by commercial logging, timber harvesting, fuel wood gartering and shifting cultivation. The head waters of Nyando lie in another of Kenya’s large forest fragments, the Tinderet forest, which faces similar stresses. Watershed erosion and wastewater discharge are the main anthropogenic induced threats to the lake according to Oguto Ohwayo and Hacky 1991 cited in Jean-Pierre and Hugo Sarmento 2008. They contribute immersely to nutirents loading in the Lake, leading to eutrophication.The degenerating ecological integrity of Lake Victoria is thus exacerbated by the invasion of Water Hyacinth Weed (Eichhornia crassipes) which first appeared on Lake Victoria in the Uganda waters in 1989. Its stationery fringes were estimated to cover 2,200 ha along 80% of the shoreline by 1995 reports Naro 2002 cited in J. l. Chapman 2002. Lake Victoria catchment is characterised by a history of land use changes. The arrival of the new railway line from Mombasa coast in Kenya in 1900 forced colonial British government to establish a large fishing industry on the lake. They introduced gill nets which allowed a large number of Cichlids to be caught. The new industry drew settlements of local people and immigrants to the lake side. As land was cleared for agriculture, soil, pesticides and fertilizer began washing into the lake through run off from the region’s frequent rains. Furthermore, the influx of immigrant workers that were attracted by large sugar estates established by Indians in the surrounding watersheds of Kakira and Lugazi, contributed tremendously to population increase, necessitating amplified food production on unprotected landscapes. . Global warming models show that East Africa will experience increased wet season rain, reported by Doherty et al 2010 cited in N Turyahabwe 2014. Nutrients loading in the lake through runoff therefore will increase unless measures are put in place to control soil erosion. The problem is further compounded by decline of native fishery, which forces lakeside communities to engage in subsistence agriculture on fragile unprotected landscapes.

Excess soil nutrients especially phosphorous attached to soil particles is washed down to the lake by runoff causing eutrophication, a process that triggers the growth and spread of Water Hyacinth Weed on the lake’s water surface. The weed forms a dense mat, blocking sunlight for organisms bellow including fish and plants that grow under the water; and starves fish and plankton of oxygen reducing the diversity of aquatic life. The free floating weed affects local economy adversely, destroying the local fishing industry and cutting off all communities form trade by blocking channels used by boats.

Water hyacinth weed also affects water supplies to adjacent cities and hydro power generation by blocking water channels and dams. The weed has become a breeding place for disease vectors such as mosquitoes and snails which transmit Malaria and Bilharzia respectively thus becoming a serious threat to public health. On its wider ecosystem restoration program in the region, EPIC strives to rehabilitate and restore biological diversity of Lake Victoria fish species through recovery programs of threatened species set out in protected areas. The following section discusses the project designed to address Eutrophication in Lake Victoria.

2. Methodologies and approaches applied

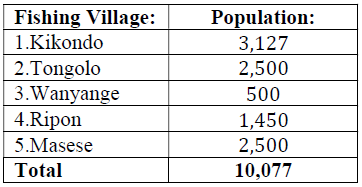

The initiative was initially conceived during a 4-day residential national workshop on Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) organized by EPIC with financial support from Satoyama Development Mechanism (SDM) in August 2016, at YMCA Jinja. The workshop was followed by a baseline survey in three (3) of the five (5) target communities. The project covers Five (5) Lake Side communities namely:

The project was formerly launched in 2018 titled: ”Establishment of Vetiver grass nursery and hedgerows for control of Eutrophication in Lake Victoria” It aims at controlling soil nutrients loading in the lake which triggers the growth and spread of Water Hyacinth Weed, through treatment of farmers’ crop fields in the catchment and on landing sites with Vetiver grass (Vetiveria zizanioides) hedge rows. Local council chairmen of target villages were selected by the first community meeting to serve as coordinators of the project in their villages. Coordinators select trainees among other things and forward the list to EPIC, which organizes training.

The project established a 2-ha Vetiver grass nursery (Mother garden) in March 2019 to serve as a source of plant material. Vetiver slips are offered to farmers free of charge. Hands-on training in a field set-up for farmers and Village Based Trainers (VBT) was carried out to equip them with skills for pegging out contour lines in their fields, planting and maintaining Vetiver hedgerows. Vetiver hedgerows block runoff as a result water infiltrates the ground. Soil nutrients are retained behind the hedge thereby enhancing fertility and moisture retention levels in the crop fields.

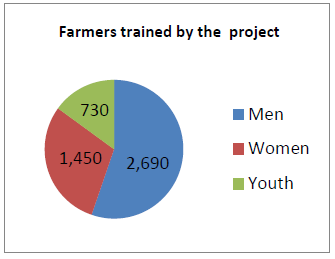

A total of 4,870 farmers (2,690 men, 1,450 women and 730 youth) have benefited from our training program so far. Due to the outbreak of covid 19 a few gardens were treated with VGT. Nevertheless, Vetiver hedgerows are seen in the uploaded photos below growing well in farmers’ gardens that received plant material and training before the outbreak of Corona virus. Kikondo has 1,563 farmers that have established VGT, the highest number among the five villages participating in the project. Tongolo has 1,118, Ripon has 821, Wanyange 233 and Masese has 1,646 farmers that use vetiver hedgerows in their crop fields.

Hitherto landing sites on Lake Victoria are main entry points of soil nutrients. They are a conduit of large volumes of sediment that flow to the lake through runoff and washes down these sites void of vegetation. The project has established Vetiver hedgerows on all landing sites in target area to control the flow of sediment. It has also stabilized a sharp cut in Ripon using Vetiver grass root system. The roots are unique, in depth they can penetrate up to 2.5 meters and in the intensity and network they can form. These features help Vetiver grass to anchor itself so firmly in the ground that it cannot be dislodged by strong floods. The tensile root strength properties of Vetiver grass in association with its inherited morphological roots characteristics, improve resistance of soil slopes to shallow mass stability and surface erosion. The tensile strength of Vetiver roots is as strong as or even stronger than that of many hard wood roots which have been proven positive for root enforcement in soil slopes.

Wanyange landing site had the worst invasion of Water Hyacinth weed. However currently 90% of sediment and pollution that used to flow into the lake is now blocked perfectly by Vetiver grass barrier and has created a natural terrace. Sediment levelled the ground behind Vetiver hedge hence reducing the gradient and its erosive force. Water hyacinth weed is starved and has retreated from the shoreline. Water in the lake is not dirty brown anymore but is clearer than before introduction of VGT.

3. Delivered activities and outputs

- A 2- ha Vetiver grass nursery with the capacity of producing 6,000,000 slips per harvest that serves as a source of plant material for the entire community was established in March 2019.

- 50 Village Based Trainers (VBT) of trainees were trained by the project to help farmers apply Vetiver Grass Hedge Rows Technology during and after the project lifetime.

- 5 one-day none residential field based training workshops were organised by the project for famers and VBT

- 62,500 slips of Vetiver grass were acquired and planted in the community nursery.

- Nursery tools and equipment were acquired by the project.

- Due to COVID 19 outbreak and subsequent restrictions on movement, only about 30% of clumps of Vetiver slips from the community nursery was distributed to farmers and landing sites.

-

Approximately 500 km of Vetiver grass hedge rows were established by the project.

4. Replication and scale up

A partner organization called Youth Environment Service (YES), operating on the Eastern side of Lake Victoria in Malaba river ecosystem in eastern Uganda, has expressed interest in a joint undertaking with EPIC. The proposed project will replicate Vetiver Grass Technology in Malaba, to address severe soil erosion in the degraded swamps of River Malaba. The beneficiaries of the planned activities are mainly small holder farmers and other resource users in the river ecosystem. Plans are underway to organize training for farmers and subsequently supply them with Vetiver grass plant material. A similar project is intended for Mountain Elgon region, where farmers will be supported to protect their cultivated land with Vetiver hedgerows as a component of the broader program for landscape stabilization.

In yet another development, EPIC and FAO agreed in principle to form partnership for the purpose of strengthening efforts geared at scaling up of Vetiver Grass Technology in the project area and in the entire riparian community. Training of farmers using Farmer Field School (FFS) approach is perceived as the most effective practice for this community based initiative. High demand for plant material from none targeted communities such as industries and large scale agriculture enterprises, is a positive development for the entire watershed but requires additional resources which are beyond limits of EPIC. This is another area where FAO is expected to fill gaps. Under EPIC-FAO collaboration, it is planned that the project area will be expanded to cover more riparian communities from the villages of:-Bukamunye, Busaana, Bukwambi Nanso A, Nanso B, Kaleega, Namabere and Tongolo 2. Furthermore project life span will be extended for another 1 to 2 years to allow ample time for proper establishment of hedgerows, in order to ascertain project impact. Extension services including establishment of Vetiver hedgerows in farmers’ fields, replacement of dead slips, distribution of slips, monitoring growth and progress of Vetiver hedgerows and work respectively, will benefit from the planned collaboration.

5. Environmental impact

Soil nutrients and fertilizers are trapped with sediment and remain behind the hedgerows, only water oozes through the leaves of Vetiver grass. Reduced flow of pollution in Lake Victoria curtails nutrients supply to water hyacinth weed hence slowing its growth and gradually causing its dearth. These efforts contribute to achievement of Aichi Biodiversity Target 8 -By 2020, pollution, including from excess nutrients, has been brought to levels that are not detrimental to ecosystem function and biodiversity. Control of spread of Water Hyacinth Weed has reduced the incidence of malaria and Bilharzia whose vectors, mosquitoes and snails respectively, use water hyacinth as a breeding place. Aquatic life deep in the water is revitalized through increased sunlight penetration and high concentrations of oxygen.

6. Sustainable development impact

Application of Vetiver grass hedgerows in gardens has improved soil fertility because nutrients and sediment loaded runoff are blocked by Vetiver grass barriers and remain in the crop field. The natural barriers enable blocked rainwater to infiltrate the soil hence increasing the moisture content in the garden. In relation to SDG2-Zero hunger, farmers have increased their crop yields and enhanced food security in the region as a result of new measures. Farmers in the project area need not use chemical fertilizers to replenish soil nutrients in their fields, thereby achieving SDG12-Responsible consumption and production. Control of growth and spread of water hyacinth weed has improved water quality and reduced the risk of catching malaria and Bilharzia, thus contributing to SDG 3-Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all. Furthermore, when pollution in the lake is reduced and controlled through watershed protection with Vetiver hedgerows, water security of lake side communities is enhanced qualitatively and quantitatively in accordance with SDG-6 – Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.

7. Resilience

Protected watersheds are resilient to global warming shocks in case of prolonged draughts or heavy rainfall. For instance, Vetiver grass leaves stand strong at 1.5 m high and slows down the velocity of runoff in torrential rain fall. Vetiver hedgerows block runoff and allow water to infiltrate soil in large volumes hence replenishing ground aquifers consequently enhancing moisture retention levels in the fields that can last for the entire dry spell. Its strong fibrous roots grow to the depth of 3 m. The roots hold the soil firmly reducing the risk of landslides in extreme torrential rainfall. VGT is affordable and easy to use. Farmers can do the whole work on their own at no cost. This nature based vegetative technology is cost effective compared to other engineering works. Farmers are self-sufficient in applying VGT. The established hedgerows in farmers’ gardens become source of plant material for expansion.

8. Social inclusion

The community based initiative is staged at the grassroots level where social inequalities are bound due to different levels of wealth, education and power status. As a general rule the project belongs to the entire community irrespective of the above mentioned differences. All adults are eligible to participate. Both the rich and poor get the same treatment in terms of service delivery. If anything the needy receive special attention to make sure that they are not left in the periphery. The project issued guidelines to village coordinators on selection of trainees in order to have a balanced and inclusive representation. Training is conducted in both English and the local language Lusoga. The youth, women, indigenous people, and immigrants were the main categories from which participants for the training were drawn. During community meetings everybody is encouraged to contribute and share. Dominant figures are not allowed to bulldoze everybody in the meeting or to impose their views on others. Meetings are convened and chaired by EPIC Secretariat which is duty bound to reduce inequalities to the lowest level possible and ensure social inclusiveness in the course of implementing the project.

9. Gender equality

The initiative is gender sensitive to the extent that does not override societal norms. Women have the same rights as men in matters related to project activities. They are free to talk in meetings and are empowered to chair some Ad hoc committees where need arises. As a principle all men only and all women only meetings for the project are not allowed. Furthermore village coordinators were issued a circular on selection of trainees to the effect that gender balance is emphasized. Having said that, however, in some instances married women in the African family setup, may not make decisions affecting land management. The project requires that women should be consulted before the new technology is introduced on family land to win their support. To a certain extent voices of women participating in the initiative are now reckoned.

10. Vision

Surrounding watersheds protected with VGT, in a mosaic landscape of agriculture and rich biological diversity that sustains crop production and climate change resilience, at the same time controlling nutrients and sediment loading in Lake Victoria.

11. Key messages

The most important achievement is that the initiative created awareness on dangers associated with Water hyacinth weed and the significance of VGT as a remedy, to the extent that Vetiver glass which was hardly known to target community is now highly valued by everybody. At the beginning of the project the grass was left unattended at the nursery site for weeks and nobody touched it. Currently there are reports of missing Vetiver grass from the nursery and from farmers’ crop fields. The stolen grass is used for mulch, fodder and for covering wet bricks, according to local sources. The community driven innovation is making concrete changes on the ground both on farm and landscape levels.

The following lessons were learnt. One, during dry spells, the best time to water seedlings in the nursery is at sunset or late in the evening in order to have the desired impact. Moisture is retained in the nursery for longer throughout cool nights than on hot days. Vetiver grass did not only survive the draught but also each slip produced 90-100 tillers in the first three months instead of the anticipated first 6 months. Two, the input of local leaders in selection of trainees is crucial to dissemination of the received knowledge and skills in target community. Leaders know better the abilities and conducts of their subjects. They know who can deliver and is willing to serve the community. However they can use nepotism in selection or favour their friends. The selection list therefore should be verified and confirmed by training organizers.

12. Opportunities and Challenges

The project offered EPIC the opportunity to interact with local authorities and elders in target community and to share concerns regarding the deteriorating environmental integrity of Lake Victoria. Joint planning for future management of the SEPLS was carried out. It was particularly intriguing to be there at this very time when our services were most needed by the community. Local authorities accentuated our timely presence in the region and offered the project public land on which to establish a large scale Vetiver nursery for the community and a project field office for long term engagements and restoration undertakings. In course of implementing the project we interacted with various stakeholders at global, regional, national and subnational levels with whom we exchanged views on pertinent issues thus learning quite a lot. We were thrilled to apply the novel technology of nature based VGT for the first time ever in providing effective solutions to Lake Victoria’ s problem of eutrophication, which is associated with the spread of water hyacinth weed on the lake. It is envisioned that restored Lake Victoria ecosystem will improve the status of biological diversity conservation. Reduced pollution will minimise public health problems and inevitably unlock investment capital with a shift towards more enterprising ventures rather than spending on public health. In wake of restored ecosystem, the altered balance of ecosystem goods and services shall be reversed to the advantage of local economy, food security and livelihoods of riparian communities. Restoration undertaking provides a chance to explore new management structures for the resource whose problems emanate from defective management.

Lake Victoria ecosystem restoration work is threatened by several challenges that include lack of resources to address problems as viewed from the southern perspective. Like any other investments in Lake Victoria region which are more often than not externally conceived and financed, Ecosystem restoration activities remain at the mercy of donors and international development agencies taking us back to square one. In order to avoid unsustainable utilisation of the lake resource, currently used as a mega fish pond for European and Middle East markets, restoration of native fish species diversity is crucial. However the question is who is going to finance the activity? Moreover conservation gurus remain silent about loss of biological diversity in LVB partly because the region is a source of cheap supplies of proteins for lucrative markets in rich countries. Paradoxically there is net transfer of proteins from a food deficit region to serve markets of wealthy nations. The prevailing poverty and malnutrition among riparian communities raises the moral question besides the illegality of using Lake Victoria as a fishpond for exotic predator alien Nile perch (lates niloticus). Secondary, Vetiver Grass Technology has proved to be effective in controlling nutrients loading in the lake, pollution and sedimentation. For instance at Wanyange landing site on lake Victoria in Uganda where VGT is applied, Vetiver barriers utterly blocked nutrients and sediment entering the lake hence leaving water hyacinth weed starved. However VGT is opposed by proponents of grey technology for obvious reasons. It does not require sale or movement of investment capital because any farmer given plant material can apply the technology at little or no cost. It is well established that grey technology in watershed protection is not only costly but also is unsustainable and ineffective. Reluctance of profit motivated financial institutions to invest in nature based technologies including VGT is critical to ecosystem restoration efforts. Lack of awareness of the value of investing in nature undermines the zeal to repair the damage we inflicted on nature thus putting in jeopardy global economy and survival of human life on earth. Global warming effects portray the fragility of global economy in gradual reactionary power of nature when disrupted by anthropogenic activities.

13. Traditional knowledge and culture

The main lesson we learn from traditional Knowledge is that it was prohibited to cultivate on land adjacent to the lake. It is further claimed that settlements on lakeside are not traditional but rather evolved with changing lifestyles and as a result of dwindling fish catches that triggered high competition for the resource. In the context of Lake Victoria, the influx of immigrant workers and job seekers who were aliens to local communities were forced to settle on no man’s land on the lake side and so were homeless people and individuals that were expelled from their communities or homesteads. Probably this explains why levels of crime are very high on landing sites or in fishing villages. However the history of lakeside settlements dates back beyond a century implying that it has now become a tradition. Lack of laws or policy to discourage the practice of lakeside settlements exacerbates the problem with grim consequences for environment in terms of pollution and habitat destruction.

14. Conclusion

Eradication of Water Hyacinth weed therefore is paramount in realising Lake Victoria ecosystem restoration since it threatens aquatic life, the entire fishery and livelihoods besides being a breeding place for disease vectors. To this end therefore the option of harnessing and harvesting the weed for economic benefits, is totally unacceptable viewed from societal and ecological norms. Furthermore Lake Victoria is recognised as international waters, therefore its management and regulation should not be entirely the responsibility of riparian states or merely augmented by global initiatives. It is proposed that a global management mechanism for international waters should be established and works closely with regional experts to oversee day to day resource utilisation and running of recovery programs in SEPLS

References

African Great Lakes International Conference: Conference concept, 2-5 May 2017, Entebbe Uganda.

Njiru, M, Waithaka, E, Muchiri, M, van Knaap, M and Cowx, I G 2005, Exotic introductions of the fishery of Lake Victoria. What are the management options? Lakes and Reservoirs: Research and Management 2005 10:147-155

Chapman, L J, Chapman, CA, Kaufman, L, Witte, F, and Balirwa, J 2008, Biodiversity conservation in African inland waters: Lessons from the Lake Victoria region, Plenary lecture, Verh. internat, Verein. Limnol. Vol. 30, Part 1, pp. 16-34 Stuttgart.

Descy, JP, Sarrmento, H 2008, Microorganisms of the East African Great Lakes and their response to environmental changes: Freshwater reviews 1, pp. 59-73

Turyahabwe, N 2014, Perceptions on fishery trends in Lake Victoria: Master thesis in International Fisheries Management. Norwegian College of Fishery Science.

Pringle, R M, 2005, The Nile perch in Lake Victoria: Local responses and adaptations.

Biography: Practitioner with over 20 years’ experience in environmental work. Serves as Managing director for EPIC Secretariat. Studied international environmental policy, at The Open University United Kingdom.