Re(Connecting) with the Ifugao Rice Terraces as a socio-ecological production landscape through youth capacity building and exchange programs: A conservation and sustainable development approach

13.12.2019

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

University of the Philippines Open University, Los Baños

DATE OF SUBMISSION

13 December 2019

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Philippines (Ifugao Province)

KEYWORDS

capacity building, exchange program, conservation, sustainable development, Ifugao Rice Terraces, tablet-based learning

AUTHOR(S)

Joane V. Serrano, PhD1, Aurora V. Lacaste1, Janele Ann C. Belegal1, Consuelo dL. Habito, PhD1, Mark Anthony F. Rabena2, Francis Mark Dioscoro R. Fellizar2, Sherry B. Marasigan, PhD 2, Inocencio E. Buot, Jr., PhD1, Noreen Dianne S. Alazada1, Thaddeus P. Lawas, PhD2, Marissa P. Bulong, PhD3, Eulalie D. Dulnuan3, Martina B. Labhat, PhD3, Elpidio Basilio, Jr., PhD3, Romeo A. Gomez, Jr., PhD4, Melanie Subilla5,Von Kevin B. Alag1

1University of the Philippines Open University, Los Baños 4030, Laguna, Philippines

2University of the Philippines Los Baños, Los Baños 4031, Laguna, Philippines

3Ifugao State University, Lamut 3605, Ifugao, Philippines

4Benguet State University Open University, La Trinidad 2601, Benguet, Philippines

5Mountain Province Polytechnic State College, Bontoc 2616, Mountain Province, Philippines

Corresponding Author: Joane V. Serrano, PhD

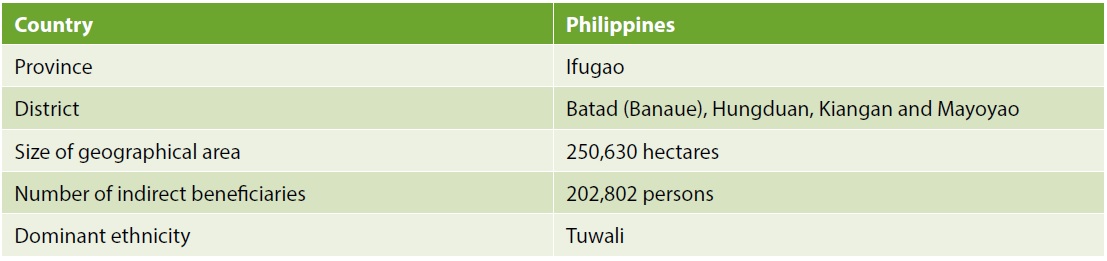

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Abstract

The Ifugao Rice Terraces (IRT) in the Philippines was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1995 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. In 2005, the Food and Agriculture Organization also inscribed it as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems site, the first in the Philippines. Despite these recognitions, the IRT faces various challenges such as under-management of biocultural diversity and socio-ecological systems, poor maintenance, abandonment of rice terraces, unregulated tourism activities, and out-migration of young Ifugaos. To address these, rehabilitation efforts and initiatives have been initiated by various sectors to restore conditions in the IRT and aid in its conservation and sustainable development. This paper examined the youth capacity building and exchange program which intended to reconnect Ifugao youths and connect urban youths with the IRT as a socio-ecological production landscape (SEPL). The youth capacity building and exchange program was implemented to address the knowledge transfer and out-migration problems confronting the IRT. Through a conservation and sustainable development approach, the program was executed in four phases: needs analysis, development of tablet-based training modules, youth training and exchange program, and contextualization of the training modules. The needs analysis indicated that the youths are still interested in being involved in the conservation and sustainable development of the IRT as a SEPL and recommended the integration of digital platforms to help them understand and appreciate their culture better. Based on these needs, experts from collaborating universities developed tablet-based training modules with the following topics: IRT as a Satoyama Landscape; Ecosystem Services of the IRT Landscape; Sustainable Development in the IRT; My Culture, My Nature and My Heritage; and, IRT as a Satoyama Landscape in the 21st Century. Results showed that Ifugao youths revisited the importance and value of IRT; however, there were overlooked values (e.g. traditional knowledge and living in harmony with nature). Additionally, these youths reported that they see the IRT only for its aesthetic and recognition value. On the other hand, the urban youths were able to connect to the knowledge and value systems of the Ifugao culture, through the exchange program, thus, enabling them to learn the values of Ifugao towards IRT and nature. It is recommended that the program be expanded to other youths in the IRT landscape and other SEPLs.

1. Introduction

Over the years, drastic changes in the natural environment, global economy, and societal conditions have negatively affected ecosystems and contributed to climate change, habitat destruction and natural resources depletion. Human activities heavily influence these changes in the human attempt for active and dynamic adaptation, survival, and development. For a continuous supply of natural resources, humans have learned to manage materials and to adapt to the environment. Thus, sustainable systems were created. These unique systems are based on a congruous relationship with the natural environment and encourage balanced and effective land and natural resources management. Sustainable systems like socio-ecological production landscapes (SEPLs), a term coined by the Japan Satoyama Satoumi Assessment, are dynamic systems that reflect human-nature interactions compatible with maintenance, resource generation, conservation and sustainable use (Centre pour l’Environnement et le Développement [CED] et al. 2010). As SEPLs are resource and service providers to their local communities and external populations, conserving and sustaining these systems are vital.

Recent conservation perspectives emphasize the relationship between nature and culture, and the role of communities in conservation and sustainable development. Van Oudenhove and colleagues (van Oudenhove, Mijatovic & Eyzaguirre 2010) emphasize that communities have molded SEPLs through generations of coevolution—exhibiting the compatibility of human needs with conservation goals. Since human activities “have significant influences in shaping SEPLs” (Ichikawa et al. 2010, p. 178), the role of indigenous and rural communities in conservation must be accentuated in proposing and planning conservation projects. Nonetheless, SEPLs are not entities fixed in time. No amount of conservation can retain their ‘initial’ characteristics since these systems are dynamic and constantly evolving. However, industrialization and a diminishing rural population, to name a few socio-ecological problems, threaten these landscapes, as implied by Belair et al. (eds. 2010). A diminishing rural population, primarily caused by youth out-migration, is one of the problems confronting a renowned SEPL in the Philippines—the Ifugao Rice Terraces.

1.1 Ifugao Rice Terraces as SEPL

Covering a total area of approximately 263,000 hectares, Ifugao province is a landlocked and generally mountainous landscape characterized by thick forests, creeks, and streams that are tributaries to major rivers. Ifugao is situated within the Cordillera mountain range in the Northern Philippines. With eleven municipalities, the province is home to an approximate 203,000 people who mostly belong to the Ifugao ethnic group, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA 2016a). Christianity, among other religions, has a growing religious influence in the province. This observance of Christianity is believed to have contributed to the disregard of indigenous traditions and belief systems, which in turn affects the management and sustenance of the landscape (Department of Environment and Natural Resources [DENR] 2008). In terms of economic activities, the Ifugao people commonly engage in farming, wood carving and weaving.

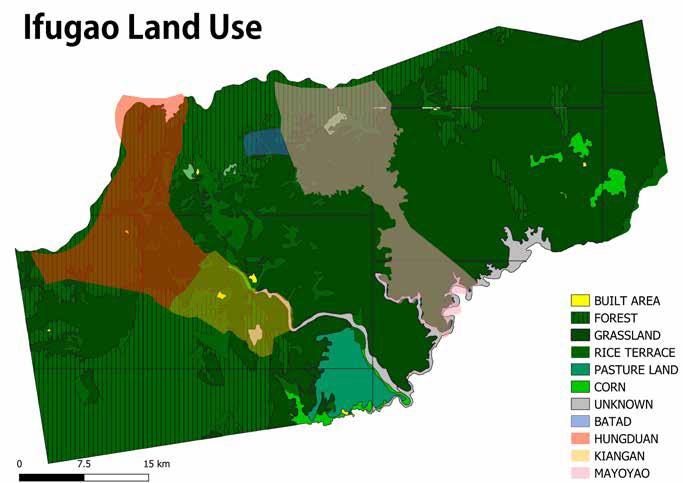

The five rice terraces, collectively called the Ifugao Rice Terraces (IRT) constituting the World Heritage Site, are in four municipalities (Banaue, Hungduan, Kiangan, and Mayoyao). Inscribed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1995 as a World Heritage Site, the IRT is also the only Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) site in the Philippines declared by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2005 and finalized in 2011. Figure 3 presents the four rice terrace clusters of the IRT. The IRT, a SEPL influenced and sustained by accumulated traditional knowledge and sustainable practices, is the primary source of the livelihoods of the Ifugao communities through providing food and income. It also provides vital regulating services such as biodiversity conservation (through organic agriculture), carbon sequestration and nutrient cycling, soil and water conservation, and pest regulation (DENR 2008). A typical Ifugao community, shown in Figure 4, consists of a muyung (community forest or private woodlot), payoh (rice terraces), and boble (village/residential area). These components of an Ifugao community are harmoniously interrelated—the muyung provides water and nutrients to the payoh, which provides harvest to residents in the boble, and the residents must tend and maintain the muyung and payoh the whole year round for food production and biodiversity.

Despite the abundance of resources and services in the rice terraces, many terraces farmers still consider themselves poor. Farming in the rice terraces “is labor intensive but with low economic returns” (DENR 2008, p. 11). This notion of farming causes youth out-migration and the eventual abandonment of the rice terraces. Out-migration poses a threat to IRT sustainability and Ifugao traditional knowledge transfer. Traditional knowledge (TK) stems from generations of harmonious human relationships with nature. Expressed through certain traditions, customs, and rituals, TK guides a community’s interaction and utilization of land and resources—resulting in sustainable practices (CED et al. 2010). Therefore, TK has a significant role in landscape, biodiversity, and ecosystem services maintenance. If not transferred to young Ifugaos, they will lack the values that promote co-existence and co-adaptation with nature. Dialogues with elders, parents, and youths revealed that Ifugaos value formal education, and parents encourage their children to get degrees at the expense of transferring TK. Marasigan and Serrano (2014) support this notion, but they also emphasize the importance of parents instilling the values of farming, environmental stewardship and culture bearing in their children.

Aside from out-migration and TK loss, the following internal and external pressures also threaten the management of natural resources and conservation of the IRT: land abandonment, under-management of biocultural diversity, aging and diminishing population due to out-migration, neglect of traditional agricultural practices, poor maintenance, urbanization, unregulated tourism activities, and farmers’ economic difficulties (Paleo 2010; Ichikawa et al. 2010; Matsui, Kawashima & Kasahara 2010). These lead to more abandoned rice paddies, unsustainable plantations, and weakening of traditional social systems. Nonetheless, Ichikawa and colleagues (2010) suggest that these problems can be addressed with raised awareness and capacity building among stakeholders.

1.2 Youth for Ifugao Rice Terraces

In response to the need for capacitating IRT community stakeholders, a project intending to reconnect Ifugao youths and connect urban youths with the IRT was implemented from November 2016 to June 2019. Youth for Ifugao Rice Terraces (Y4IRT), a tablet-based capacity building and exchange program for Ifugao and urban youths, is a collaborative two-year project of the University of the Philippines Open University (UPOU), Kanazawa University (KU), University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB), and Ifugao State University (IFSU). A one-year joint initiative to the project, the contextualization of instructional materials, was also executed from March 2018 to March 2019 for the Ifugao community. These two projects were funded by Mitsui & Co., Ltd. and the Satoyama Development Mechanism, respectively. Currently, the capacity building program only targets Ifugao youths as they can have immediate influences on the IRT. To specifically address the out-migration and knowledge transfer problems, Y4IRT was implemented to capacitate IRT successors to sustain the biodiversity and ecosystem services of the landscape. Y4IRT was comprised of four (4) phases executed through a conservation and sustainable development approach: needs analysis, development of tablet-based training modules, youth training and exchange program, and contextualization of training modules.

This chapter examines the youth capacity building and exchange programs in terms of their contribution to IRT as a SEPL. Furthermore, this study aimed to understand the views of the youth participants on the pressing issues of IRT, and on the services and values derived from the landscape. This chapter also aims to narrate the process, lessons learned, and views of youth participants on the modules and activities in developing and deploying the tablet-based capacity building and exchange program.

2. Description of Activities

2.1 Study Sites

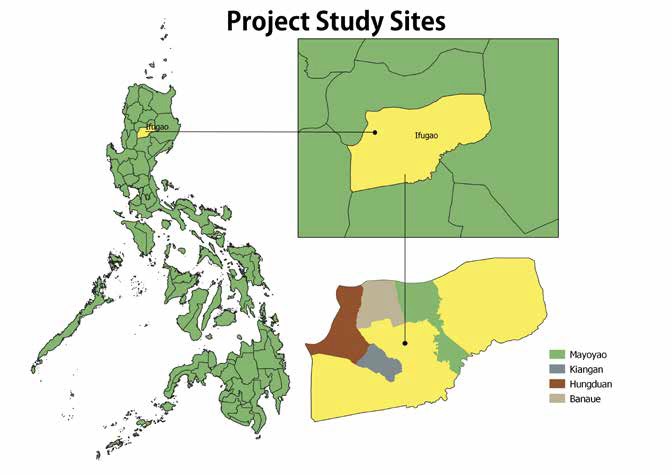

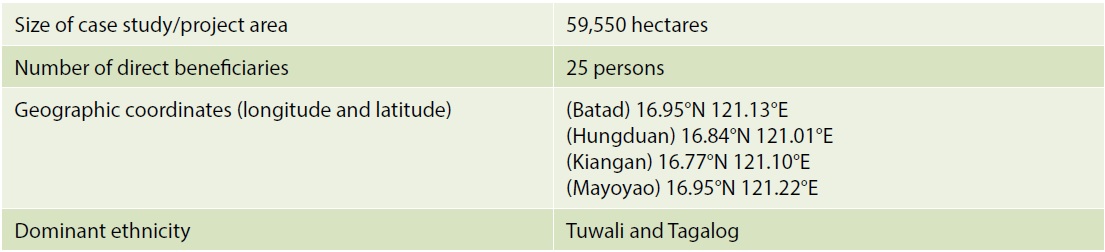

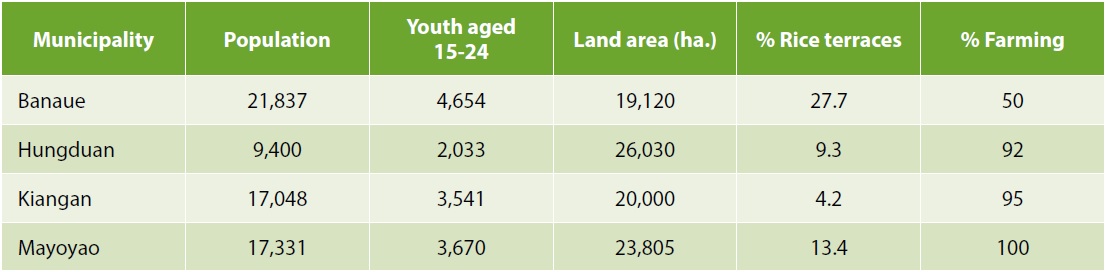

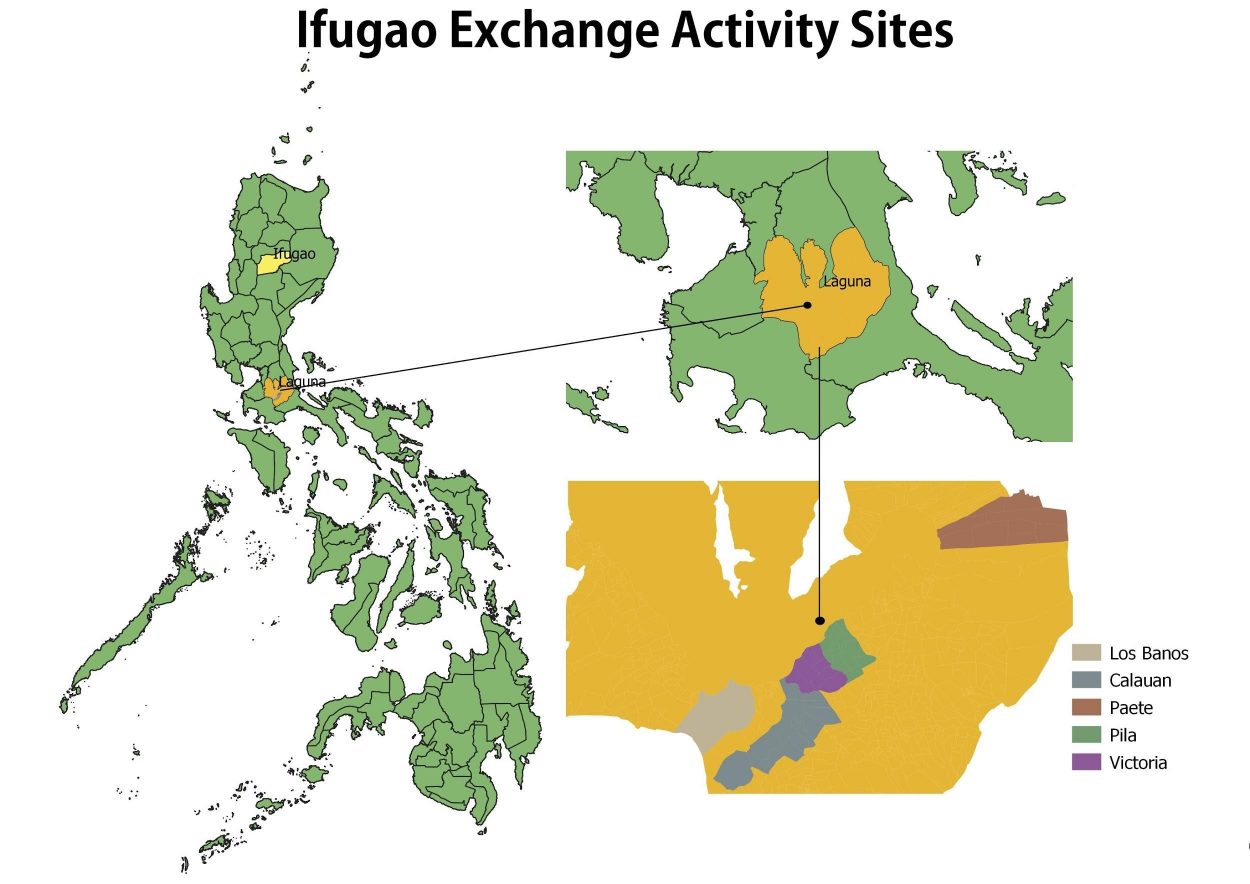

Chosen study sites were Banaue, Hungduan, Kiangan, and Mayoyao. These municipalities, covering an estimated 85,000 hectares collectively, are situated adjacent to one another (see Fig. 1). Rugged terrain, extensive rice terraces, rivers and lakes, and forests characterize the study sites (see Fig. 2). Agriculture is the main economic driver of these municipalities, with most of their land dedicated to food production. Residents of the municipalities also engage in tourism, wood carving, weaving, and blacksmithing. Table 1 presents the demographic and geographic information of each municipality.

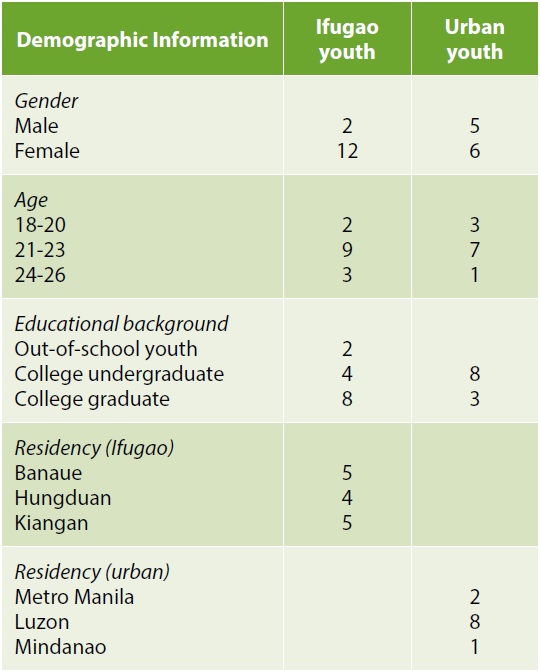

2.2 Youth participants

Table 2 presents the demographic profile of Y4IRT’s youth participants. There were 14 Ifugao youths, and 11 urban youths. It was observed that most Ifugao youth participants were female, and most participants were aged between 21-23 years old. All participants are at least high school graduates. Youths from the three main islands of the Philippines (Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao) were not equally represented in the program, as most urban youths were from Luzon. As indicated in the table, there were two Ifugao out-of-school youths who were working as tour guides in their municipalities after graduating from high school.

2.3 Activities

This study was conducted using a case study approach. Defined by Crowe and colleagues (2011, p. 1), the case study approach is an “in-depth, multi-faceted exploration employed to obtain an in-depth appreciation of an issue or event of interest, in its natural real-life context”. Based on this approach, Y4IRT’s phases were carried out, and the views and narratives of the Y4IRT youth participants on the services and values derived from the IRT landscape were elucidated. The 4 phases of Y4IRT transpired as follows:

2.3.1 Needs analysis

Since Y4IRT produced educational materials, it was imperative to conduct a needs analysis prior to material development. Youth needs, problems, knowledge gaps and challenges addressable by Y4IRT were identified through interviews and workshops. Specifically, key informant interviews with village elders and government officials, and focus group discussions (FGDs) with youths, farmers, educators, and residents of IRT communities were conducted (see Fig. 5 and 6). The utilized interview guides are included in Appendix 1. Stakeholders were asked about the values they attribute to the IRT landscape in terms of natural and cultural heritage. Photos and video footage of Ifugao and related activities were also taken. Consents for interviewing and photo/video documentation were granted by the involved community stakeholders. These activities were accomplished to ensure user-involvement, to deliver the training modules in a proper context, and to tackle the most pressing issues relevant to IRT conservation and sustainable development.

In the initial discussion with the Ifugao youth, IRT presence in social media and other digital platforms was suggested for improving youth appreciation towards the IRT. With this, a digital tools and skills assessment among selected Ifugao youths was conducted to determine the acceptability and accessibility of tablet-based modules to the target group.

2.3.2 Development of tablet-based modules

Considering the identified gaps and needs, the training modules were developed with pertinent topics and multimedia materials through a series of writeshops, meetings, and online correspondences with content experts, instructional designers, and course writers. Course writer meetings and workshops, as shown in Figure 7, were regularly held to revise and ensure the completeness and quality of the training modules. Field visits and interviews among community stakeholders were conducted to ensure information validity of the modules. The modules were regularly evaluated and revised by the course writers in consultation with content experts and were pretested among selected youth and stakeholders. Peer reviews from partner universities were also considered pretesting and evaluation. Due to the limited Internet connectivity in Ifugao, the modules were deployed through an offline tablet application developed for the project.

2.3.3 Youth training and exchange program

The youth training and exchange program was conducted as an avenue for cultural and social exchange between Ifugao and urban youths. Participants from Ifugao and urban areas were invited through social media platforms and direct invitations; however, participants were recruited on a voluntary basis. Application forms were submitted to the project team, and participants were accepted based on their volunteer work, advocacies, and IRT perceptions. Youths who seemed to be physically fit and driven towards conservation and sustainability were chosen. The topics discussed in the modules were the basis and guide of program itineraries and activities to make the program holistic, engaging, and informative. This exchange program was separated into two activities: Ifugao youth and urban youth exchange activities, which took place in Laguna and Ifugao, respectively.

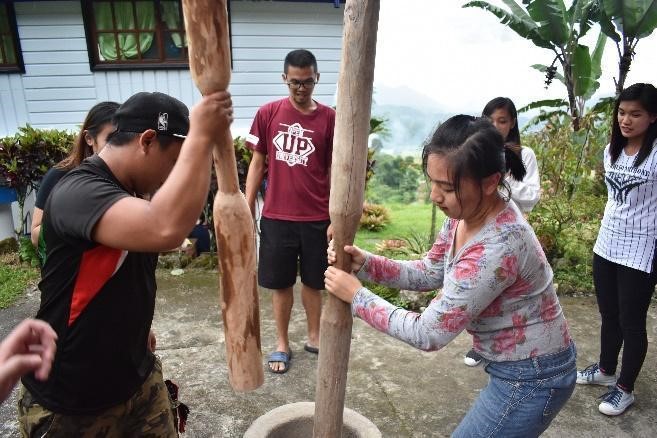

For the urban youth exchange activity, the participants were brought to Ifugao for a three-day immersion activity wherein they learned about the Ifugao culture and rice terraces landscape. The program occurred in Batad (in Banaue), Hungduan and Kiangan with the following activities: lectures on IRT ecosystem services and culture, learning and performing cultural dances, appreciation of a few local flora and fauna, interviews with elders and community members, immersions with foster families, and a synthesis activity (see Fig. 8 to 11).

For the rural youth exchange activity, Ifugao youths went to Laguna province for a three-day activity designed to expose them to different institutions and communities in the urban setting. Laguna is a predominantly urban province situated in Southern Luzon. Distinguished academic institutions (like UPOU and UPLB), heritage sites (old churches), commercial establishments, and local craft businesses (e.g. wood carving) characterize the province. The exchange took place in five municipalities, namely: Calauan, Los Baños, Paete, Pila and Victoria (see Fig. 12).

This exchange activity also aimed to equip the Ifugao youths with knowledge and ideas they can apply to their respective communities. Through the activity, the Ifugao youths were able to experience firsthand the contrast between Ifugao and an urban area. Program activities were: lectures on sustainable development, site and institution visits, interactions and observations of livelihood programs in relocation communities, interviews and study on textile, paper, and forest products technology, wood carving industry, and heritage house preservation, and a synthesis activity (see Fig. 13 to 16). Furthermore, the tablet-based modules were only given to and utilized by the Ifugao youths.

Note: Trolley pushing is a form of transportation on inactive train tracks.

2.3.4 Contextualization into translated materials

As a joint initiative of Y4IRT, the developed training modules were translated into two local dialects: Ayangan and Tuwali. This initiative will sustain Y4IRT’s impacts by making the modules more relevant to a wider scope of community stakeholders. Experienced English-to-local-dialect translators, who were retired teachers and community elders, were identified by IFSU colleagues. This choice of translators assured the congruent context between the locally translated and English modules. Evaluation workshops with other experts and selected community stakeholders were also conducted to ensure the materials’ validity. Conclusively, the translated materials were well-received by the evaluators and stakeholders.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Addressing needs through tablet-based modules

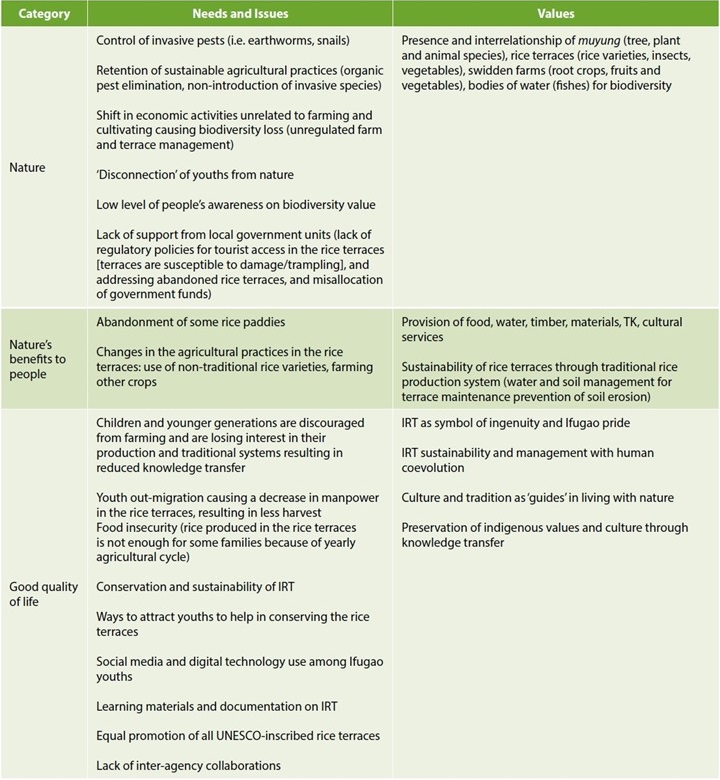

Categorized according to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) multiple values of nature (MVN) framework (IPBES 2015), Table 3 shows the needs, issues, and Ifugao values identified during the needs analysis. Among all needs assessed, these were the most pressing/recurring: knowledge transfer to younger generations, attracting youths to conservation projects, digital technology to engage youths, IRT learning resources, and emphasizing the values in sustaining the IRT.

Although not explicitly mentioned during the needs analysis, it was deduced that most youths do not readily recognize and appreciate the intrinsic value of nature. However, data indicated that youths were interested in being involved in the conservation and sustainable development of the IRT and suggested the use of digital tools. To entice youths in involving themselves and appreciating the IRT, digital modules were developed. The digital assessment yielded results indicating Ifugao youths are digitally proficient and can utilize digital materials (computer=57, tablet=46, smartphone=44, Internet=58, search engine=60). Full results are shown in Appendix 2.

The contents of the training modules were written based on the identified needs, issues, and values, and based on the following principles: is engaging for youths; does not use terms/concepts that are too technical since target audience is both uneducated/educated youths; introduces and discusses scientific topics; contains actual, relevant and valid IRT information; and utilizes multimedia materials and interactive learning activities. Briefly described in Appendix 3, the training modules discuss natural landscapes, sustainable development, ecosystem services and culture.

These tablet-based training modules, shown in Figure 17, are comprehensive innovations in the development and delivery of education and training programs. Since Ifugao is a remote province with limited Internet accessibility, accessing the modules using a portable and mobile device through a non-Internet-dependent application was the project’s approach. Having tablet-based training modules makes it easier for target youths to learn more on the IRT as they can access the materials anytime, anywhere, through a single device.

There are existing frameworks, policies, and organizations involved in the conservation of the IRT. Initiatives (forest, agriculture and water management, tourism, livelihood assistance, restoration and conservation) for the IRT are abundant, from local government units (LGUs), non-government organizations (NGOs), academia, and private institutions. Y4IRT differs from other initiatives since it focuses on the youths through value ‘(re)connection’ and digital education. Furthermore, Y4IRT can attain long-term sustainability as opposed to other efforts.

3.2 Values perceived during the exchange program

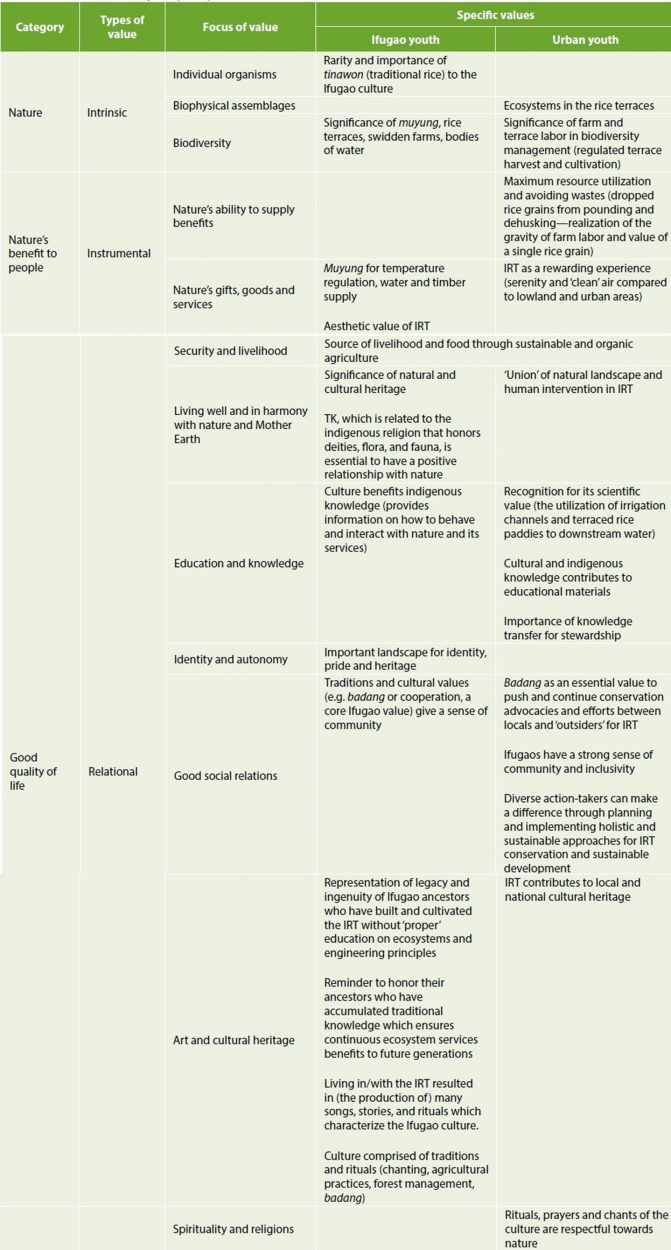

With the exchange program, the youths interacted with each other, resulting in the interchange of ideas and reflections. This in turn affected their current perceptions and value of IRT conservation and sustainable development. Views about the values of the IRT were shared by the youths during the respective synthesis activity of their exchange programs. Table 4 summarizes these views into the MVN framework (IPBES 2015).

Additionally, one core Ifugao value, as narrated by the Ifugao youths, is their belief that they belong to the land, and that the resources they acquire from the landscape are not truly theirs, and therefore must be replaced to ensure a sustainable supply of resources. However, just as the value for TK, the Ifugao youths are admittedly ‘indifferent’ towards this value they must possess as IRT successors. They also shared that they sometimes overlook the IRT’s significance and only perceive its aesthetic and recognition values. Nonetheless, the Ifugao youths believe that interacting with elders and older adults, who strongly embody the Ifugao values, must be done to instill the same gravity of the values in them.

Furthermore, the Ifugao youths have also stated that learning some information about the IRT through the modules has influenced their perceived values. It is noteworthy to report that the Ifugao youths, after witnessing the views of the urban youths, or the ‘outsiders’, were able to ‘reconnect’ and ponder on the significance of their culture and the IRT. Moreover, three major points about the rural-urban life contrast emerged during their synthesis activity: recognition of the importance of having permanent residences in their family/ancestral land and of not having problems related to housing, encroachment, and relocation; appreciation of innovations and technology on sustainable practices (maximizing resource utilization); and acknowledgement of government roles in providing support (e.g. livelihood programs and assistance).

For the urban youths, although they showed an appreciation for IRT, they only recognized its ‘theoretical’ value as they are not its direct beneficiaries. These youths have ‘less grasp’ of the extent of the IRT’s importance to the Ifugao people. Nonetheless, through the exchange, they indicated that they were ‘connected’ to other knowledge and value systems by the introduction and immersion in the Ifugao culture. These youths shared that the immersion became an avenue for them to be more concerned and involved individuals on the IRT’s conservation and sustainable development since they saw and experienced firsthand the importance of the landscape to Ifugao livelihoods and culture.

As the Ifugao and urban youths embody significantly different cultures and values, evidently their concept and appreciation of the IRT differ as well. For Ifugao youths, who have a culture of intimate relationships with nature, TK and sustainable practices, it is expected of them to appreciate and regard nature better than the urban youths. Nevertheless, through Y4IRT, the youths improved their current knowledge and values for the IRT and nature and improved their conviction to contribute to the conservation and sustainable development of the landscape.

Diverse youth perceptions were evident in this study; however, these results are not representative of the Ifugao and urban youth populations. Moreover, this study acknowledges a potential data bias from the skewed female-male distribution of the Ifugao participants. Although the project tried to evenly invite youths to the program, still few Ifugao male youths joined. Literature indicates that males are less likely to participate in studies or in trainings due to indifference (Holloway et al. 2017; Boyle et al. 2011; Markanday et al. 2013).

3.3 Assessment and monitoring of Y4IRT’s sustainability

The assumption of the project is that the Y4IRT’s modules will be used by other youths and sectors, and both Ifugao and urban youths, to sustain their engagement in similar sustainable development engagements. Through follow-up FGDs, field visits, and interviews with the youths, the sustainability and extent of use of the modules (by other youths, sectors, and partner academes) will also be assessed after six months and a year after the project has concluded. Monitoring these activities can be performed with an established youth network for continued communication and coordination with IFSU and Ifugao LGUs. Additionally, Ifugao youths were tasked to devise an action plan as part of the activities in the tablet-based training modules. These plans must engage and mobilize their communities in initiatives/actions that will benefit the ecosystem and the IRT (i.e. proper waste management in tourism spots, agri-ecotourism, and tradition documentation). Discussing the youths’ progress, through field visits and online correspondences, on their action plans is also one of the monitoring strategies of the project.

On the other hand, monitoring the Ifugao youths’ progress and measuring the knowledge gained with the training modules can also assess the impacts of the project. This can be accomplished by consolidating the outputs from the learning activities and self-assessment questions in the modules.

After acknowledging the learnings from the pilot run of the Y4IRT, it is recommended to plan for and carry out a more inclusive and effective implementation of the project, and to develop a framework that can be used by the community to evaluate the impact of education and capacity-building initiatives on the maintenance of the SEPLs. Indicators will be used to assess whether the outcomes led to tangible improvements such as behavioral change.

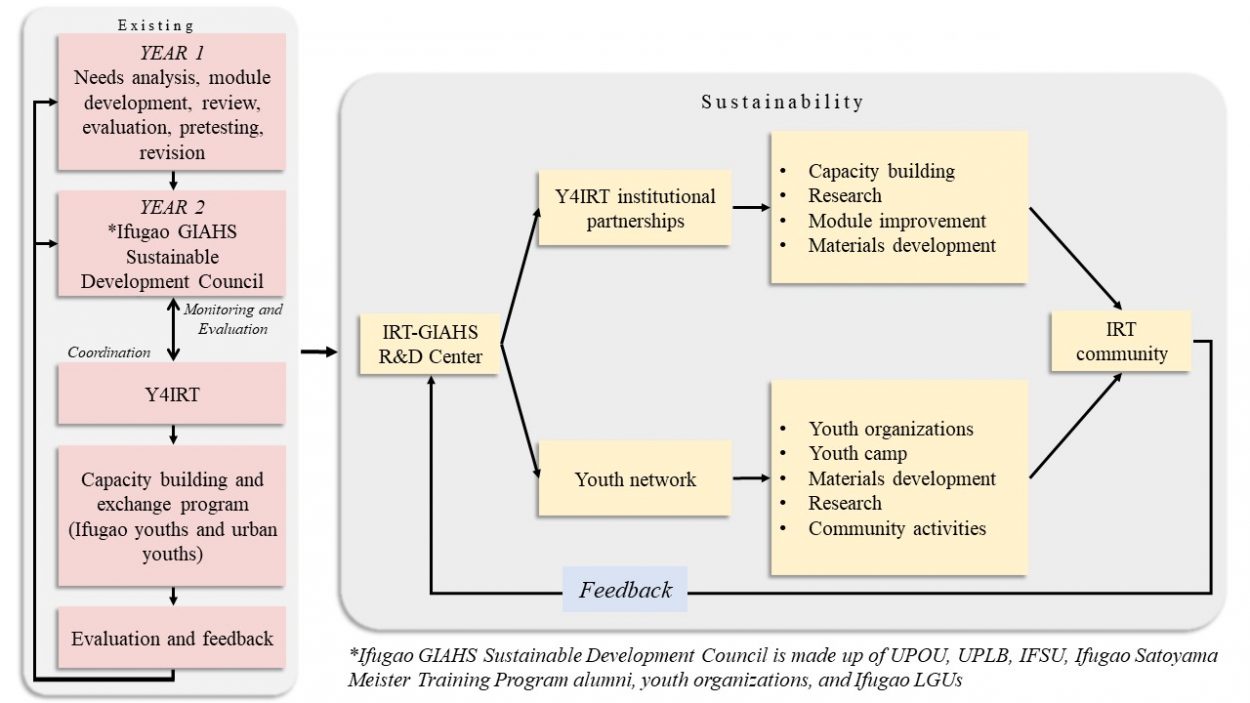

3.4 Institutional frameworks

Figure 18 presents the guiding and sustainability frameworks of Y4IRT. The tablet-based modules will be situated in the IRT-GIAHS Research and Development Center (IRT-GIAHS R&D Center) at IFSU-Lamut, Ifugao. The Center will be a space for collaboration among institutional partners and the youth. For Y4IRT’s sustainability, activities to be undertaken by institutional partners and youth networks are listed in the framework. Execution of these activities will result in various materials to be presented to IRT communities for feedback. Returning feedback to the Center repeats the process, and these interactions will translate to sustained community interest for IRT sustainability.

3.5 Challenges, opportunities, and biodiversity benefits of Y4IRT

The Y4IRT was challenged in logistics and recruitment. Distance, schedules, other responsibilities, and weather conditions made visits to Ifugao limited and often cancelled. Youth availability and schedules also affected the progress of the exchange program. However, when field visits were postponed, online correspondences and meetings were conducted to accomplish project tasks.

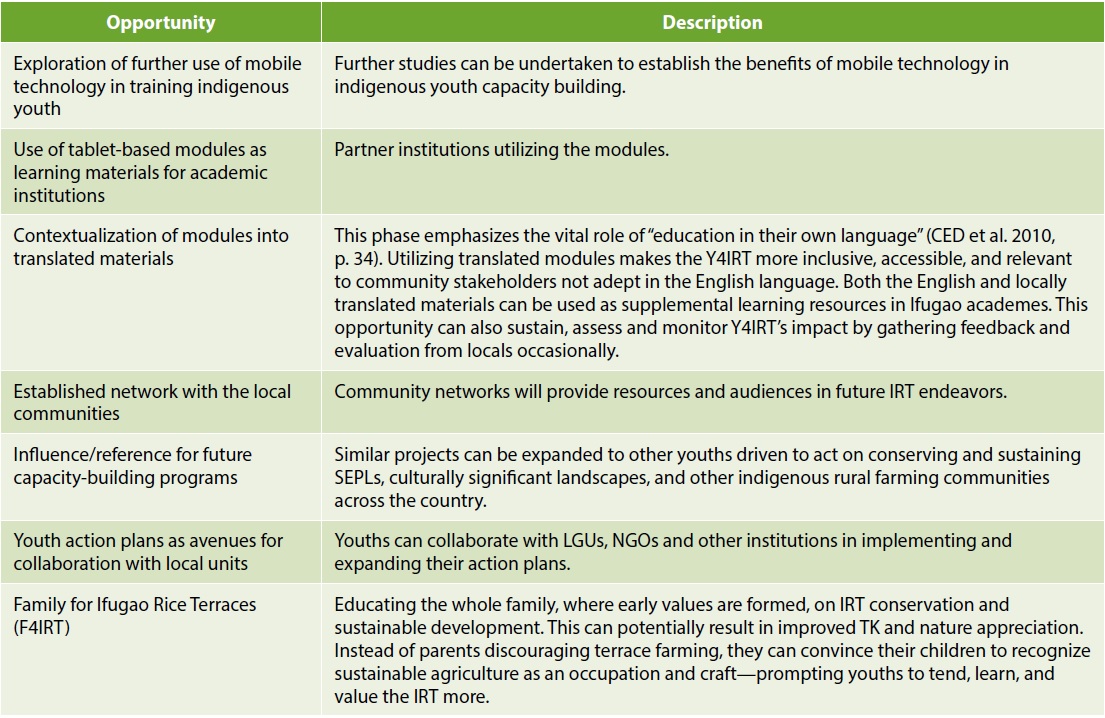

On the other hand, Ifugao youths, especially males, were difficult to recruit to the exchange program. The call for participants resulted in an influx of urban youths, but only a few Ifugao youths responded—which forced IFSU project members and colleagues to personally invite some youths. The project team expected many aspiring Ifugao participants since they were Y4IRT’s target. This could reflect a lack of drive among Ifugao youths to act and sustain the IRT and its biodiversity, resulting in the non-participation of young Ifugao males in training programs. Perhaps a longer and more intensive period of recruiting participants could be included in future programs. It is recommended that a study on indigenous youth non-participation (factoring in gender and socioeconomic aspects) in education and training programs be conducted. In addition to the challenges, opportunities to sustain Y4IRT impacts are identified and discussed in Table 5 below.

In line with the opportunities, the biodiversity benefits of Y4IRT are projected through execution of the biodiversity conservation activities discussed in the tablet-based modules: regulating and continuous silviculture, strict tree-cutting regulations and policies, efficient utilization of timber crops, multiple cropping in swidden farms, regular production in the rice terraces (traditional rice farming, then during the fallow period, vegetable farming), and regulated pesticide use. These could be incorporated into the action plans to be executed by the Ifugao youths.

4. Conclusion

Capitalizing on digital technology, Y4IRT utilized tablet-based training modules which provided information on the IRT, Ifugao culture, ecosystems, and sustainable development. Through these modules, the Ifugao youths reportedly gained new knowledge about the landscape. Their values towards IRT were influenced by the modules and by the urban youths’ views. Similarly, the urban youths have experienced and gained a deeper understanding of the IRT and Ifugao culture. These value (re)connections will strengthen, maintain, and build the youths’ positive relationship with nature that benefits the conservation and sustainability of the IRT.

Alongside increasing the knowledge and improving the values of the youths, it is also necessary to develop stewards who will initiate change and will advocate and commit to sustainability. This case signifies the role of individuals and communities inside and outside of Ifugao for sustaining SEPLs such as the IRT. After Y4IRT, youth participants have the capacity to mobilize community stakeholders for additional IRT management practices and policies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Y4IRT project team and participants, the translators, the Ifugao Satoyama Meister Training Program, and their colleagues from UPOU, UPLB, IFSU, KU, Benguet State University, Mountain Province Polytechnic State College, and the provincial government of Ifugao. The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to Dr. Koji Nakamura for his guidance and support to this initiative; and to Mitsui & Co, Ltd. and the Satoyama Development Mechanism for funding Y4IRT and the contextualization of the training modules, respectively. They also thank those who provided their comments on earlier versions of this manuscript: SITR authors and editors, IGES, UNU-IAS, and the Satoyama Initiative.

References

Belair, C, Ichikawa, K, Wong, BYL & Mulongoy, KJ (eds.) 2010, Sustainable use of biological diversity in socio-ecological production landscapes, Background to the “Satoyama Initiative for the Benefit of Biodiversity and Human Well-Being”, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal.

Boyle, T, Landrigan, J, Bulsara, C, Fritschi, L & Heyworth, J 2011, ‘Increasing study participation’, Epidemiology, vol. 22, p. 279.

Centre pour l’Environnement et le Développement, Association Okani, South Central Peoples Development Association, Organisation of Kaliña and Lokono in Marowijne, Inter-Mountain People Education & Cultures in Thailand Association & Forest Peoples Programme 2010, ‘Customary sustainable use of biodiversity by indigenous people: case studies from Suriname, Guyana, Cameroon and Thailand’, in Sustainable Use of Biological Diversity in Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes, eds C Belair, K Ichikawa, BYL Wong & KJ Mulongoy, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, pp. 23-35.

Crowe, S, Cresswell, K, Robertson, A, Huby, G, Avery, A & Sheikh, A 2011, ‘The case study approach’, BMC Medical Research Methodology, vol. 11, no. 100, pp. 1-9.

Department of Environment and Natural Resources 2008, The Ifugao Rice Terraces Philippine Project Framework, viewed 20 June 2019, <http://www.fao.org/3/a-bp814e.pdf>.

GADM 2011, Country provinces, viewed 25 April 2019, <http://philgis.org/country-basemaps/country-provinces>.

GADM 2011, Ifugao administrative boundaries, viewed 25 April 2019, <http://philgis.org/province-page/ifugao>.

GADM 2011, Laguna administrative boundaries, viewed 25 April 2019, <http://philgis.org/province-page/laguna>.

Holloway, EM, Rickwood, D, Rehm, IC, Meyer, D, Griffiths, S & Telford, N 2017, ‘Non-participation in education, employment, and training among young people accessing youth mental health services: demographic and clinical correlates’, Advances in Mental Health, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 19-32.

Ichikawa, K, Wong, BYL, Bélair, C & Mulongoy, KJ 2010, ‘Overview of features of socio-ecological production landscapes’, in Sustainable Use of Biological Diversity in Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes, eds C Belair, K Ichikawa, BYL Wong & KJ Mulongoy, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, pp. 178-82.

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) 2015, Preliminary guide regarding diverse conceptualization of multiple values of nature and its benefits, including biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services (deliverables 3 (d)), viewed 12 June 2019, <https://www.ipbes.net/dataset/methodological-guidance-diverse-values-and-valuation/resource/1c3fbeaf-e98e-4d97-97c0>.

Marasigan, SB & Serrano, JV 2014, ‘Indigenous farming families of Ifugao: Partners in safeguarding the sustainable use of natural resources’, International Association of Multidisciplinary Research Journal of Ecology and Conservation, vol. 10, pp. 103-16.

Markanday, S, Brennan, SL, Gould, H & Pasco, JA 2013, ‘Sex differences in reasons for non-participation at recruitment: Geelong osteoporosis study’, BMC Research Notes, vol. 6, p. 104.

Matsui, T, Kawashima, T & Kasahara, T 2010, ‘Town revitalization through the promotion of historical and cultural heritage in the community of Kanakura, Machino Town, Wajima City, Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan’, in Sustainable Use of Biological Diversity in Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes, pp. 136-139.

Paleo, UF 2010, ‘Surveying the coverage and remains of the cultural landscapes of Europe while envisioning their conservation’, in Sustainable Use of Biological Diversity in Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes, eds C Belair, K Ichikawa, BYL Wong & KJ Mulongoy, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, pp. 45-50.

Philippine Statistics Authority 2016a, Population of the Cordillera Administrative Region (based on the 2015 census of population), viewed 17 May 2019,

<https://psa.gov.ph/content/population-cordillera-administrative-region-based-2015-census-population>.

Philippine Statistics Authority 2016b, Philippine population density (based on the 2015 census of population), viewed 20 June 2019,

<https://psa.gov.ph/content/philippine-population-density-based-2015-census-population>.

van Oudenhove, FJW, Mijatovic, D & Eyzaguirre, PB 2010, ‘Bridging managed and natural landscapes: the role of traditional (agri)culture in maintaining the diversity and resilience of social-ecological systems’, in Sustainable Use of Biological Diversity in Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes, eds C Belair, K Ichikawa, BYL Wong & KJ Mulongoy, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, pp. 8-18.