Perceptions of resilience, collective action and natural resources management in socio-ecological production landscapes in East Africa

30.10.2018

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION

-

Bioversity International; National Museums of Kenya; Arizona State University; National Agricultural Research Organization; Graduate Program in Ecology and Biodiversity; São Paulo State University (UNESP)

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION

-

30/10/2018

-

REGION

-

Eastern Africa

-

COUNTRY

-

Uganda (Central Region); Tanzania (Tanga Region)

-

SUMMARY

-

If properly managed, socio-ecological production landscapes and the ecosystem services they provide can contribute to the well-being of local communities, as well as to the achievement of the global conservation agenda and of other relevant development policies at the national level. However, many of these landscapes worldwide are often highly insecure due to unsupportive government policies, agencies, and lack of local collective action. By conducting a network analysis and participatory exercises with district officials and farmers in two communities from Rakai (Uganda) and Lushoto (Tanzania) Districts, we studied local perceptions regarding (a) the contribution of natural resources to local farmers’ livelihoods, and how these farmers, in turn, contribute to the conservation and sustainable use of these natural resources, (b) landscape threats and resilience, and (c) major causes of the identified and possible local solutions for mitigating them. The study shows that in the four communities there was very little communication among farmers and that the cooperation between farmers and local and district stakeholders was rather limited. Farmers did not seek much information concerning conservation and use of natural resources and very few of them were aware of the existence of government programs regulating natural resources management. In addition, the study sites were found to be experiencing a progressive degradation of their natural resources. We, therefore, conclude that the creation of spaces for informed, public discussion aimed at making the institutional context more favourable for the creation and coordination of community groups and at enhancing their interaction, would contribute to a wider movement of knowledge and social exchange that, in turn, could ultimately result in the creation of local initiatives aimed at the conservation of natural resources and of the services they provide.

-

KEYWORD

-

Ana Bedmar Villanueva (Bioversity International), Yasuyuki Morimoto (Bioversity International), Patrick Maundu (National Museums of Kenya), Yamini Jha (Arizona State University), Gloria Otieno (Bioversity International), Rose Nankya (Bioversity International), Richard Ogwal, Bruno Leles (São Paulo State University), Michael Halewood (Bioversity International)

-

AUTHOR

-

Ana Bedmar Villanueva (Bioversity International), Yasuyuki Morimoto (Bioversity International), Patrick Maundu (National Museums of Kenya), Yamini Jha (Arizona State University), Gloria Otieno (Bioversity International), Rose Nankya (Bioversity International), Richard Ogwal, Bruno Leles (São Paulo State University), Michael Halewood (Bioversity International)

-

LINK

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

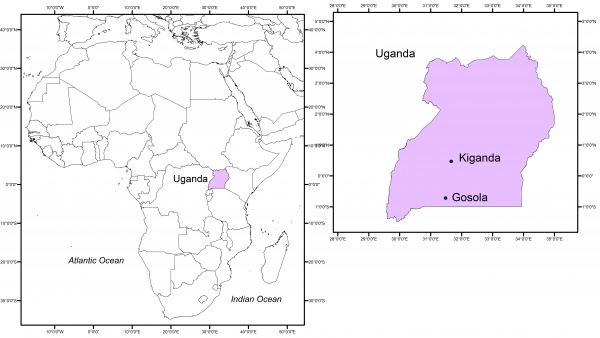

| Country | Uganda |

| Province | Central Region of Uganda |

| District | Rakai |

| Size of geographical area 1 | 3,351.5 Km2 |

| Number of indirect beneficiaries 2 | 492,441 persons |

| Dominant ethnicity | Baganda |

| Country | Tanzania |

| Province | Tanga Region |

| District | Lushoto |

| Size of geographical area 1 | 4,091.62 Km2 |

| Number of indirect beneficiaries 2 | 518,008 persons |

| Dominant ethnicity | Sambaa |

Figure 2. Map of the country and case study region – Tanzania

Uganda:

| Size of case study/project area 1 | …………… hectare |

| Number of direct beneficiaries 2 | 31 persons |

| Geographic coordinate (longitude and latitude) | 0° 43′ 0″ S, 31° 24′ 0″ E |

| Dominant ethnicity | Baganda |

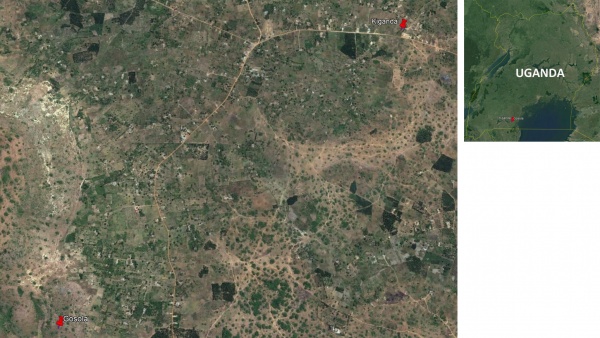

Figure 3. Land use and land cover map of case study site – Uganda

Tanzania:

| Size of case study/project area 1 | …………… hectare |

| Number of direct beneficiaries 2 | 45 persons |

| Geographic coordinate (longitude and latitude) | 4° 47′ 55″ S, 38° 17′ 25″ E |

| Dominant ethnicity | Sambaa |

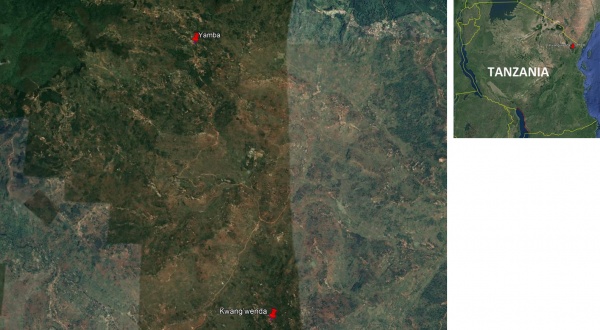

Figure 4. Land use and land cover map of case study site – Tanzania

1. Introduction

One of the outcomes of the 10th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP 10) was the adoption of the “Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020” (CBD 2010). Among the key features of this Strategic Plan was the establishment of 20 Aichi Targets to achieve global biodiversity conservation. In particular, Target 11 addresses the need to establish and manage protected areas as effective tools for meeting environmental challenges. However, conservationists agree that protected areas are not the only tools for maintaining ecosystems (Woodley et al. 2012) and that in a concerning number of cases, the protected areas are not as effectively protected as they should be (Jones et al. 2018). As a result, the importance of integrating protected areas into the broader landscape is increasingly recognized (e.g. Ervin et al. 2010), and doing so is aimed at guaranteeing the conservation of ecosystems and the services that they provide.

The term socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS) defines “a mosaic of production landscapes (or seascapes) that have been shaped through long-term harmonious interactions between humans and nature in a manner that fosters well-being while maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem services” (Gu & Subramanian 2012, p.7). In some cases, SEPLS are formally recognized as protected areas under different frameworks. Many others are not recognized as such, yet they contribute to the conservation of both biological and cultural diversity. Resilient SEPLS are crucial for securing ecosystem services, benefiting local communities’ well-being and, at the same time, contributing to the global conservation agenda. In this context, “resilience” of a SEPLS is understood here as the ability of a SEPLS to absorb or recover, in terms of both ecosystem processes and socio-economic activities, from various pressures and disturbances without lasting damage. The importance of functioning ecosystems for the poorest and most vulnerable societies in the light of climate change it is widely recognized (e.g. WRI 2005). In fact, as climatic events become more severe, well-managed ecosystems such as forests or wetlands can buffer many flood and tidal events, landslides and storms. However, many of the SEPLS that integrate these ecosystems are comprised by so-called “common-pool natural resources”. Common-pool natural resources, including forests, pastures, water systems, fisheries and biodiversity, are typically defined as rivalrous (i.e., one person’s use of a resource detracts from others’ use of the same resource), and non-excludable (i.e., it is difficult or impossible to prevent others from accessing the resource). Consequently, natural resources are commonly threatened by a number of factors such as population pressure, expansion of agriculture and unsustainable agricultural and rangeland practices, land fragmentation, poor implementation or enforcement of natural resource management policies, and the loss of traditional knowledge and weakening of customary institutions. Managing natural resources amidst the added stresses associated with climate change constitutes a challenge (Tompkins & Adger 2004). In the case of agricultural production systems, in particular, climate-related stresses may potentially lead to a progressive increase in smallholder farmers’ reliance on natural resources and hence contribute to their further erosion and eventual loss in the absence of supportive policies, agencies, and local collective action initiatives designed to counteract these effects. In this context, collective action, understood as the coordination of efforts among groups of individuals to achieve a common goal when individual self-interest would be inadequate to achieve the desired outcome (Ostrom 1990), might be essential to enhancing the sustainability of natural resources management (e.g. Abramovitz et al. 2001; Tompkins & Adger 2004).

This study draws on original research conducted as part of the Policy Action for Climate Change Adaptation (PACCA) project, implemented under the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). The authors focus on identifying local perceptions regarding (a) the contribution of natural resources to local farmers’ livelihoods, and how farmers, in turn, contribute to the conservation and sustainable use of these natural resources, (b) landscape threats and resilience, and (c) major causes of the identified threats and possible local solutions for mitigating them, in four study sites located in Uganda and Tanzania.

This chapter is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the study sites, the methodology is presented in Section 3, Section 4 deals with the results, Section 5 with the discussion of the findings, and finally, Section 6 concludes with some policy implications.

2. Study sites

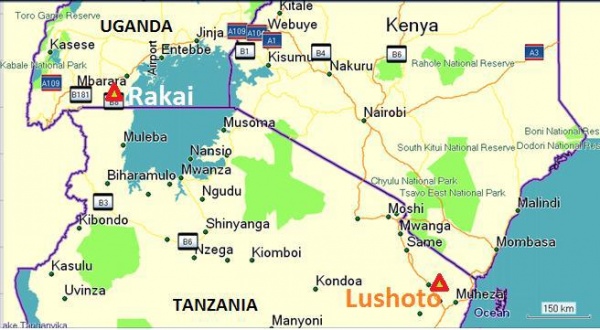

The study was carried out in Yamba and Kwang’wenda, two representative villages of the Lushoto District of the Tanga region in Tanzania and in Kiganda and Gosola, two villages of the Rakai District in the Kyovu Parish, in Lwanda Sub-county of Uganda (Fig.5). Rakai and Lushoto are ecologically similar in many aspects. The Sambaa, the dominant tribe in Lushoto, and the Baganda tribe of Rakai are predominantly farmers, with livestock keeping in both cases a minor occupation. The four selected sites were chosen because they were among the benchmark sites of CCAFS.

Figure 5. Location of Rakai (Uganda) and Lushoto (Tanzania)

The two villages in the Lushoto District are separated by a straight distance of about eight kilometers and are located in the West Usambaras, a mountainous region ranging in altitude from 500 to over 2,300 meters. Yamba is representative of forest-edge villages with high resource diversity. It is located next to an escarpment, below the 1670m Yamba hill. Yamba differs from Kwang’wenda in two main ways: the village is next to a forest (Mkuzi forest), and it is higher in elevation, making it cooler and hence more humid. Although the main parts of Yamba are at 1540m above sea level, the village extends both to higher (1600m –Yamba mountain) and lower altitudes (1400m). Around the center of Yamba village, the population density is high, and the land is highly cultivated. Kwang’wenda is representative of villages with relatively fewer resources and with little or no influence on forests. It is located on a hilly area above Soni town at an altitude of approximately 1175m. The environment has been altered drastically by human activity over the years.

Kiganda and Gosola, in Rakai, are located on the inland part of the western shores of Lake Victoria, Southern Uganda, and share a similar nearly flat landscape interspersed by small hills, forming two highly cultivated landscapes, separated by a straight distance of about five kilometers. The area is nearly devoid of rivers. Though highly populated, the area suffered considerably in the late 1980s and early 1990s due to the HIV/AIDS scourge that wiped out many families. This attracted several development agencies, which progressively left the area as the pandemic diminished.

3. Methods

Participatory exercises

A series of participatory exercises aiming at elucidating the range of perceptions of landscape resilience in the four communities were held in May and October 2014. The participants of each community were identified by a local coordinator and gathered at a central location in the village for focus group discussions. In total, 31 and 45 community members of mixed gender and age from the two villages in Rakai and Lushoto, respectively, took part in the study. At the beginning of each exercise, simple demographic information of the participants such as name, age and gender were recorded. During the exercises, all the information was written down on sheets of paper and pinned on the walls to be used by the participants as reference information during the subsequent exercises.

Introduction/brainstorming sessions

Mapping the village landscape, its diversity and natural resources maintenance over time

The participatory exercises started with the development of a map by the community members of their landscape, indicating the natural resources and the physical and infrastructural features (Fig. 2). Participants also listed the major components of their landscape, including crop land, fallow land, wild land, forests and the agricultural and wild edible biodiversity. Thereafter, participants were asked to indicate on the maps the changes that the landscape had experienced over the previous 30 years.

Trends in main food sources: past, present and expected future

To identify the main food sources for the communities and the communities’ perceptions about how these sources had changed and were likely to evolve over time, cards with pictures of the main sources of food were placed on the ground. Then, ten pebbles were given to each of the participants, who were thereafter called one at a time to allocate the ten pebbles to the different food sources according to how important each of them was at the present time. The same exercise was repeated for past and future situations (Fig.6).

Figure 6. Participatory landscape mapping exercise in Rakai, Uganda.

Community perceptions of resilience

In the context of analyzing factors affecting the perceptions of resilience of the communities, we used the “Indicators of Resilience in SEPLS”. These indicators were first developed by Bioversity International and the United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS) in 2012 as a tool for engaging local communities in adaptive management of the landscapes and seascapes in which they live. The tool consists of a set of 20 indicators designed to capture community perceptions of different aspects of their production systems: ecological, agricultural, cultural and socio-economic. Likewise, the tool includes both qualitative and quantitative indicators from answers provided by the participants. These questions fall within six sections: (i) Landscape and ecosystem diversity and its conservation status; (ii) Diversity, management and sustainable use of local resources; (iii) Documentation of local knowledge and agrobiodiversity; (iv) Landscape resource governance and institutional cooperation; (v) Gender-based knowledge and social equity; and (vi) Socio-economic infrastructure and income opportunities. Each participant gave his or her own perception of landscape resilience and people’s wellbeing with respect to each of the 20 indicators using a 5-point scale. A detailed description and assessment of the SEPLS toolkit can be found in UNU-IAS et al. (2014).

Figure 7. Participants identifying food sources on map

Before starting, the facilitator explained each indicator’s question using different techniques. The facilitator also explained the meaning of the 5-point scale. A “one” meant a “very poor” status while a “five” meant a “very good” status. Participants also ranked their perception of the future trend for each question using a similar 5-point scale. A “one” meant that the participant expected the situation to deteriorate very significantly (pessimistic) in the future, while a “five” meant that he/she considered that it would improve very significantly (optimistic). Thereafter, based on the analysis of the proportion of respondents that had given scores of 1 to 5 for each indicator, areas of risk and resilience perception were identified. Overall resilience was determined by comparing perception scores from both the current status and future trends. After scoring each indicator, participants were given the opportunity to discuss their answers. The exercise concluded with a review of the main problems and threats identified during the exercise, their causes and possible solutions.

Statistical analyses

Perception scores of questions within each of the six sections of the Indicators of Resilience toolkit were pulled together and averaged. The distribution of scores in the majority of indicators was found not to be normal according to the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. Due to the lack of normality, scores were also compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by a Dunn’s test with correction for multiple comparisons. P-values below 0.05 were assumed to be significant. Mean scores were compared between the present and future predictions within sections to test whether resilience was perceived to change over time for each of the study sites. Present and future scores of the six sections were also compared between communities to test whether there were significant differences between the perceptions of resilience of the four studied communities.

Network analyses

Social network data was collected through personal interviews to identify social ties. Two surveys were conducted: a household survey, and a meso-level expert survey. The household survey adopted an egocentric network designed to explore farmers’ communication with experts and other farmers. Through the use of network questions, farmers reported the names of experts and other farmers that they went to for information on climate-smart farming practices and technologies as well as the frequency and mode of communication with their named ties. The surveys also explored the size and composition of farmers’ networks related to natural resources use and management, and recorded data on farmers’ access to and participation in sustainable natural resources management and their perceptions about related policies. In total, 298 farmers from Rakai and 302 from Lushoto responded to the household survey. The meso-level organizations included local, district, national and international organizations relevant for climate-smart technologies and practices in the study sites. The meso-level survey used the snowball sampling method to identify all relevant experts. It used a few of the names of experts generated from the household surveys to seed the snowball approach.

One year later, the same farmers and district officials from Rakai and Lushoto were visited again to get their feedback about the results obtained from the data analyses.

4. Results

Insights from the participatory exercises

Landscape characteristics

The mapping exercise made it possible to acquire a general idea about major differences between the landscapes surrounding the four communities. The landscape around Lushoto, and particularly that of Yamba, was found to be more diverse than that of Rakai. Communities living in Yamba had access to two forest reserves, and there were three forested mountains in close proximity, several permanent rivers, streams, springs, big rocks and an escarpment with caves. In total, considering the two communities together, participants listed 31 local terms to describe physical features, land use, types of farms and crop fields. Participants from Kwang’wenda mentioned 13 (42%) of the terms, whereas those from Yamba referred to 27 (87%). Some of the components mentioned only by participants from Yamba included caves, big rocks, forests and highlands. Examples of terms that appeared in Kwang’wenda and not in Yamba were terms used to define eroded and abandoned crop fields. Participants from Rakai, on the other hand, highlighted the existence of a few swamps, ponds and one lake, as well as about six hills covered with bushes and grass, which had traditionally constituted important grazing areas and sources of firewood and medicinal plants for the community, and a few private forests.

Regarding the diversity of food available in their surroundings, the participants from Lushoto listed 149 food types, while the group from Kwang’wenda listed 110, and those from Yamba, 138. Participants from Gosola and Kiganda listed 80 food types in total. Crop fields, livestock, markets, forests and the wild environment were identified as the five most important sources of food in Lushoto. Participants from both Yamba and Kwang’wenda considered that the roles of crop production and the market had gained importance over time and were expected to continue to do so towards the future. The role of forests and wetlands was perceived differently in different villages. The participants from Yamba felt their role would decline significantly in the future. In contrast, participants from Kwang’wenda expected them to gain importance as a result of the growing efforts undertaken by the community to plant trees to restore the lands that had been degraded during the previous years. In Rakai, six food sources (crop fields, livestock, forests/wild environment, lakes/rivers, friends/relatives and the market) were identified as the most relevant. Overall, participants from Rakai perceived their own crops to be the main sources of food in the area. They perceived that it was so in the past as well as in the present, and expected them to continue being so in the future. There was a general sense that the importance of the market had increased substantially over time, and it was expected to become one of the main sources of food in the future. The role of forests/wild environment was considered to have kept constant over time, while the importance of gifts coming from friends or relatives was expected to decrease progressively due to the increasing scarcity of resources.

Collective action

Participants from Lushoto recognized the existence of organized forms of collective action to improve the welfare of the community. These included the construction of schools and other buildings, the cleaning of wells, and the planting of trees on hilltops. In addition, communities were encouraged to keep springs under some local management and to conserve indigenous water-conserving trees around the springs.

Twenty-one (21) organizations were involved in local development within Yamba. These included community-based organizations (CBOs), non-governmental organizations (NGOs), religious groups, government ministries, schools, national research institutions, the private sector, international research organizations and international development agencies.

Participants from Rakai explained that forms of collective action had almost disappeared in their area. Therefore, NGOs and CBOs constituted key players in encouraging the formation of new farmers’ organizations to improve farmers’ ability to bargain collectively on issues that affected them, such as better prices for their agricultural produce. Some forms of collective action, however, still existed in the area for taking care of the common wells. There were no bylaws regulating natural resources management and participants recognized that the few regulations established by the government were not being enforced. This was attributed to the absence of natural resources within public lands.

Eight stakeholder institutions were identified in Rakai: two CBOs, one local NGO, one international NGO, the project being implemented by the CGIAR consortium, and religious and educational groups.

Natural resources status and use

Loss and deterioration of water bodies, pasturelands, forests, wildlife, and crop diversity were some of the examples given by participants from both Lushoto and Rakai when they were asked to reflect on changes in the natural resources in their surroundings experienced over the previous 30 years. The reasons given by participants from the four communities to explain this situation were similar. These included mismanagement of natural resources, increased competition for natural resources due to population increase, changing food preferences, poor agricultural practices, poor access to seeds, climate-related factors, emergence of new pests and diseases and lack of consideration of some of the members of the community towards the others. Ineffective, or the absence of, cooperation among stakeholder groups, progressive disappearance of traditional resource management systems and lack of leadership at the local level were also pointed out as some of the main reasons behind the lack of enforcement and implementation of laws regulating natural resources conservation and use.

Overall, participants perceived that there was nothing they could possibly do about the depletion of natural resources. This was particularly true among the participants from Rakai, who indicated that as the population increased, the resources progressively decreased, weakening, in turn, the “community identity”.

Communities’ perceptions of landscape threats and resilience

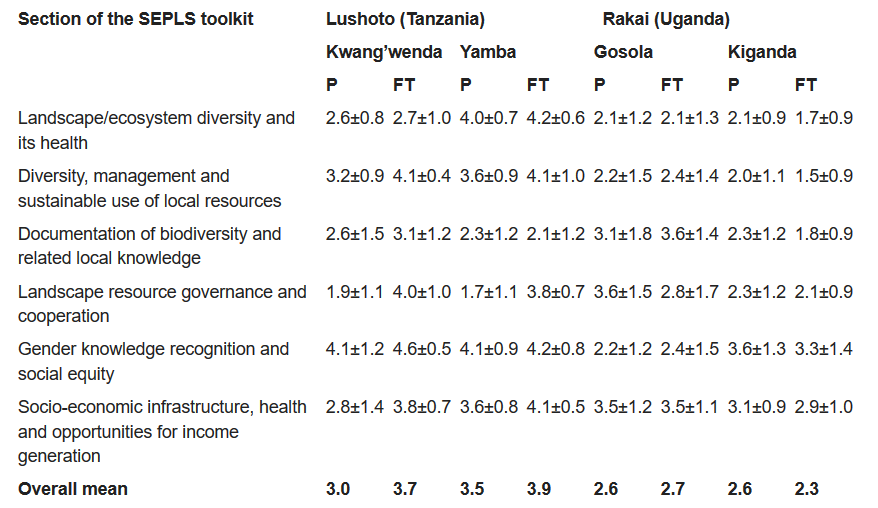

Table 1 gives a summary of the mean values given by participants from the four communities with regard to the current status and future trends (based on predictions for 30 years’ time in the future) for each of the sections covered by the SEPLS toolkit. In line with the responses given during the previously conducted participatory exercises, responses to the SEPLS exercises revealed that participants from Lushoto had the highest levels of optimism with regard to both present and future trends, with an average of 3.4 and 3.8 points, respectively, compared to Rakai, that scored “average” for both current status (2.6 points) and future trends (2.5 points). Perceptions of resilience were found to be the highest in Yamba, followed by Kwang’wenda, Gosola and Kiganda. The level of optimism regarding future trends followed a similar order.

Table 1. Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) of values for present status (P) and future trend (FT) scores for the four villages visited

Statistical analyses

The scores given by the participants from Yamba to the questions contained in the section “landscape/ecosystem diversity and its health” were particularly high. In fact, statistical analyses revealed that they were significantly higher than the scores given by participants from the other three villages for both present and future trends (P<0.001). The scores given to the questions about “diversity, management and sustainable use of local resources” for both present and expected future trends by the participants from both Yamba and Kwang’wenda were also significantly higher that the scores given by participants from the two villages in Rakai (P<0.05). We, however, did not find significant differences between the mean scores given by the participants of Kwang’wenda and Gosola for the present. In contrast, the values given by participants from Lushoto to the questions related to “landscape resource governance and cooperation” for the present time, were fairly low. In fact, they were significantly lower than those obtained in Gosola (P<0.001). However, participants from both Yamba and Kwang’wenda were optimistic with regard to expected future trends, giving significantly higher scores to the questions contained in that section for the future (P<0.001). The mean scores given by participants from Gosola with regard to expected future trends for questions related to “documentation of biodiversity and related local knowledge” were also particularly high, being significantly higher than those given by the participants from Yamba and Kiganda (P<0.05).

Insights from the surveys

Natural resources use and farmers’ awareness about norms and regulations

Despite the widespread concern expressed by the farmers during the participatory exercises regarding the steady erosion of natural resources in their surroundings, results from the survey revealed that only a few of the interviewed farmers from both countries considered themselves to be contributing to the maintenance of natural resources. In Rakai, 69% of respondents indicated that they were contributing to the maintenance of wells, pastures on hills (2%), and natural forests and wetlands (1%), whereas in Lushoto the highest level of contribution was found for natural forests, with 33% of the respondents confirming this.

Responses given by the surveyed farmers concerning the use of vacant or public land, and regarding their awareness about the existence of rules or regulations governing natural resources management, differed between the two countries. More than half (69%) of the interviewed farmers from Rakai reported use of vacant or public lands to obtain water (58%), to collect firewood (52%) and medicinal plants (51%), or for animal grazing (16%). In contrast, relatively few reported being aware of the existence of rules or regulations governing natural resources management on private or public lands. The opposite results were found for Lushoto, where very few of the interviewed farmers reported use of vacant, public or common lands (18%), and a fair amount of them reported being aware of the existence of rules or regulations. This was particularly true in the case of natural forests, for which 61% of respondents reported knowledge of rules or regulations.

Social Networks

Farmer to farmer

Although the results from Lushoto were slightly more positive, analyses revealed that the connections among farmers and between farmers and local experts were rather weak in the four study sites (Table 2). The network analysis also provided an opportunity to explore whether certain actors had structural or relational disadvantages, based on social and gender variables, that could limit their access to information or other types of resources. The results from both Rakai and Lushoto revealed that women had smaller networks compared to men. Twenty-nine per cent (29%) of the respondents from Lushoto and 27% from Rakai answered that they did not seek information about farming practices or technologies from any other farmer. Moreover, 49% of respondents from Lushoto and 59% from Rakai reported that they had no direct connections with any experts at all inside or outside their villages.

Farmer to expert and expert networks

The meso-level expert network was designed as part of the PACCA project to assess the extent to which organizations with expertise in climate-smart technologies and practices were connected among themselves and with farmers, which goes beyond the focus of this paper. However, the results presented here are still useful to understand how information and communication structures varied across sites. A detailed description of the results of the network analysis can be found in Jha et al. (2016).

The level of connectivity between expert organizations and farmers was found to be weak in the four study sites. Out of the 70 experts working in Rakai, only 18 (26%) were named by farmers. Similarly, out of the 85 experts from Lushoto, only 14 (16%) were named by farmers. The proportion of local experts not connected to farmers was greater in Rakai than in Lushoto. Along the same lines, analyses of existing connections among experts in Lushoto revealed that the experts that were connected to farmers were more embedded and prominent in the expert network (they had more connections with other experts) than the experts not connected to farmers in Lushoto. In contrast, in Rakai, experts that were connected to farmers were less embedded and less prominent in the expert network compared to Lushoto.

Figure 8. Participatory exercises in Rakai, Uganda

Figure 9. Participatory exercises in Rakai, Uganda

Follow-up workshops: views of local experts and farmers

In both countries, farmers’ lack of confidence in the local experts and their perception of the insufficient presence of extension agents on the ground was corroborated by the farmers during follow-up meetings. District officials agreed with these feelings and recognized the lack of means of the current extension system, in particular the lack of qualified personnel and necessary resources, to meet farmers’ needs sufficiently. District officials also recognized a great need to increase the use of participatory approaches and to encourage the formation of farmers’ groups to strengthen communication networks. In addition, they recognized that the extension officers’ lack of knowledge on how to address gender-related issues was constraining the effective inclusion of women in the training sessions.

Local solutions and interventions to increase resilience

The participatory exercises and follow-up workshops conducted provided space for participants to deliberate on and discuss the challenges affecting their landscape resilience and possible local solutions in the wake of ongoing socio-economic, ecological and climatic changes. Some of these included (a) initiating and strengthening tree planting programmes, (b) discouraging encroachment on forests, springs and wetlands through the enforcement of relevant government regulations and policies, (c) initiating soil conservation programmes, (d) increasing communities’ awareness of the importance of crop and landscape diversity for maintaining local ecosystem services, improving people’s nutrition and resilience, and for climate change adaptation, and (e) strengthening and building the capacity of existing institutions, leaders and community groups, including youth and women groups, in resource use and management.

5. Discussion

It is widely recognized that resilient ecosystems are key for human well-being and for supporting communities’ efforts to adapt to climate change. However, we found that the study sites presented here were characterized by a progressive degradation of natural resources in their surroundings. Participants from the four communities shared similar concerns about the decrease in accessibility to the natural resources and, as a result, to sources of wild food and firewood, among other products, and about their consequent increasing dependence on the market. The information gathered during participatory exercises suggests that at the time of conducting this study, only one of the four studied communities presented a relatively high level of confidence in their landscape and considered that its status would improve in the future. The perceptions of resilience held by the farmers from Lushoto, especially from Yamba, were considerably more positive than those of the farmers from Rakai. Several factors could explain the obtained results. The landscape of Yamba was characterized as having more components, habitats and food species. In addition, there was a larger number of agencies and stakeholders working at the community level in Lushoto, and more particularly in Yamba, than in the two studied communities of Rakai. Furthermore, the results from the analyses of expert networks indicate that farmers in Lushoto had better access to the most prominent/important expert organizations compared to the experts in contact with farmers from Rakai. The connections among local experts were also poor in Rakai compared to Lushoto, indicating that information exchange and communication among local experts were low in Rakai compared to Lushoto.

However, while the role of social networks in enabling communities to adapt to environmental changes and to successfully initiate and sustain natural resources management is well recognized in the literature (e.g. Tompkins & Adger 2004), we found that, in general, there was very little communication among farmers in the four study sites. Wosen et al. (2013) found that external sources of information, such as extension provisions, play a key role in enhancing adoption of natural resources management. In contrast, we found that not only were the connections between farmers poor, but also that cooperation and communication between farmers and local experts were almost non-existent. None of the communities studied here reported having a strong tradition of collective action oriented towards natural resources management. This could be a consequence of the lack of a sense of control expressed by the communities over the existing natural resources in their surroundings. However, we also believe that, in line with these results, and in agreement with other studies (e.g. Crona & Bodin 2006), the reported absence of collective action for natural resources management in the study sites might be also explained by the rather weak social networks existing among the community members. At the same time, the lack of enforcement of laws and rules regulating the use of natural resources makes these resources de facto “open access”. This might explain why only a small percentage of the respondents to the survey in the four communities reported to be contributing to the maintenance of natural resources in their surroundings, despite their evident awareness and concern about its loss raised during the participatory exercises.

In contrast, farmers showed optimism when they were asked to suggest potential local solutions and interventions to increase their landscapes’ resilience. That proves that there is potential in the studied communities for creating social capital for landscape governance. Going back to the study sites would allow assessment of whether the conducted participatory exercises effectively contributed to raised awareness among the participants with respect to natural resources management and to changes in the communities’ behaviour. The discussions held during the participatory exercises, and more specifically for each indicator of resilience of the SEPLS toolkit, certainly contributed to improvement of communities’ awareness of the values of biodiversity and the different components of their landscape and allowed communities to evaluate current conditions across the landscape and to identify and reach agreement on priority actions with the potential to improve the status of biodiversity conservation in their surroundings. In addition, by encouraging community members to reflect on their landscape’s resilience and how it could be improved, the indicators exercise might have given them a greater sense of ownership over management processes. The above findings suggest that the study sites would benefit from the creation or the reform of policies and institutions aimed at supporting control by the communities over natural resources and at making the institutional context more favourable for the creation and coordination of community groups. Presumably, it would likely lead to better conservation, management and use of the natural resources and ecosystems in their surroundings and of the services that they provide.

6. Conclusions

By conducting network analysis and participatory exercises with district officials and farmers in two communities from the Rakai (Uganda) and Lushoto (Tanzania) districts, we assessed the extent to which farmers relied on and were concerned about the status of natural resources available in their surroundings, their contribution to their maintenance and the different uses they were making of them. In the literature, collective action appears to be a promising approach to guarantee sustainable natural resources management. Similarly, social networks are known to have a role in the diffusion of innovations through social learning, joint evaluation, social influence and collective action processes. However, in this study we found the existence of only weak local collective action initiatives related to natural resources management. Presumably, the widespread feeling of lack of control over the natural resources of the studied communities, together with the particular institutional settings and the absence of local initiatives, have contributed to a situation in which natural resources are under threat, subject to overharvesting, land conversion and underinvestment. In addition, the weak interconnections found between the surveyed farmers and the consequent limited exchange of knowledge between them, might have also contributed to the absence of collective initiatives aiming to improve natural resources management. As a consequence, we conclude that the creation or reform of policies in the communities studied here, aimed at making the institutional context more favourable for the creation and coordination of community groups and for promoting interaction among community members and social exchange, has the potential to improve the conservation of natural resources in the surroundings of the study sites, as well as the services that they provide. This, in turn, would contribute to the achievement of the global conservation agenda.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the CCAFS for providing financial support to this research and to the many farmers and community leaders who participated in the survey and participatory exercises upon which this study is based. Thanks are also due to those who provided us with helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript and to the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) and the Satoyama Initiative.

References

Abramovitz, J, Banuri, T, Girot, PO, Orlando, B, Schneider, N, Spanger-Siegfried, E, Switzer, J & Hammill, A 2001, Adapting to climate change: natural resource management and vulnerability reduction, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IISD), Gland, Switzerland.

CBD 2010, Decision adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity at its tenth meeting, Decision X/2, Strategic plan for biodiversity 2011–2020.

Crona, B & Bodin, Ö 2006, ‘What You Know is Who You Know? Communication Patterns Among Resource Users as a Prerequisite for Co-management’, Ecology and Society, vol. 11, no 2.

Ervin, J, Mulongoy, KJ, Lawrence, K, Game, E, Sheppard, D, Bridgewater, P, Bennett, G, Gidda, SB & Bos, P 2010, Making Protected Areas Relevant: A guide to integrating protected areas into wider landscapes, seascapes and sectoral plans and strategies, CBD Technical Series No. 44, Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, Canada.

Gu, H & Subramanian, SM 2012, Socio-ecological production landscapes: relevance to the green economy agenda, United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies Policy Report.

Jha, Y, Welch, E, Ogwal-Omara, R & Halewood, M 2016, How are the meso-level expert organizations connected to farmers and among themselves? Comparing Rakai (Uganda) and Lushoto (Tanzania), CCAFS Info Note, Copenhagen, Denmark: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

Jones, KR, Venter, O, Fuller, RA, Allan, JR, Maxwell, SL, Negret, PJ & Watson, JEM 2018, ‘One-third of global protected land is under intense human pressure’, Science, vol. 360, no. 6390, pp. 788-791, <http://science.sciencemag.org/content/360/6390/788>.

Ostrom, E 1990, Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Tompkins, E & Adger, WN 2004, ‘Does adaptive management of natural resources enhance resilience to climate change?’, Ecology and society, vol. 9, no 2.

UNU-IAS, Bioversity International, IGES & UNDP 2014, Toolkit for the Indicators of Resilience in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS).

Woodley, S, Bertzky, B, Crawhall, N, Dudley, N, Londoño, JM, MacKinnon, K, Redford, K & Sandwith, T 2012, ‘Meeting Aichi Target 11: what does success look like for protected area systems’, Parks, vol. 18, no 1, pp. 23-36.

Wossen, T, Berger, T, Mequaninte, T & Alamirew, B 2013, ‘Social network effects on the adoption of sustainable natural resource management practices in Ethiopia’, International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 477-483.

WRI (World Resources Institute) 2005, A Guide to World Resources 2005: The Wealth of the Poor, World Resources Institute, Washington, DC.