Natural resources management by Rwoho forest edge communities, Uganda

25.08.2016

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Environmental Protection Information Centre (EPIC)

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

25/08/2016

-

REGION :

-

Eastern Africa

-

COUNTRY :

-

Uganda (Western Region)

-

SUMMARY :

-

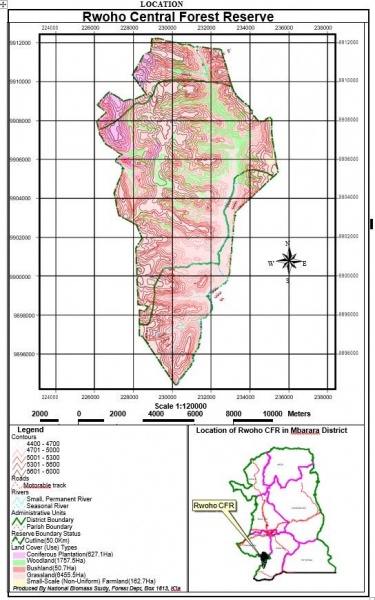

Rwoho forest edge communities comprise peasants that depend on rain-fed agriculture. The crops produced include bananas, cassava, sweet potatoes, beans, cowpeas, sorghum, maize, and millet. Coffee is the major cash crop produced. The average land holding is 2 ha. The forest reserve provides unskilled employment during the off season; however, to a large extent, the population is engaged in subsistence farming. The highlands receive an average of 917 mm of rainfall annually, and the area is a major food producer in the western region of Uganda. The Rwoho Central Forest Reserve covers an area of 9,073 ha. Adjacent communities access the resource through collaborative forest management (CFM). Limited access to forest resources has created shortages of trees and tree products for the community. Converting the forest landscape into a monoculture tree plantation has destroyed biological diversity and affects environmental services and goods derived from the forest ecosystem. Across Uganda and particularly in the Rwoho rainforest ecosystem, the number of naturally growing trees has declined because trees are cut at a very fast rate without being replaced. This has led to a loss of biological diversity, frequent landslides, floods, silting of water resources, severe soil erosion, loss of soil fertility, and decline in agricultural productivity.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Uganda, Forest communities, Wildlife, Resources

-

AUTHOR:

-

Imran Ahimbisibwe (EPIC)

-

LINK:

-

https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:5769/SEPLS_in_Africa_FINAL_lowres_web.pdf

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.