Multi-Stakeholder Platform for Coastal Ecosystem Restoration and Sustainable Livelihood in Sanniang Bay in Guangxi, South China (SITR8-11)

21.03.2024

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

Farmers’ Seed Network

DATE OF SUBMISSION

19/09/2023

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

China

AUTHOR(S)

Yufen Chuang

Xin Song

Guanqi Li

LINK

1 Introduction

1.1 Environmental and Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Area

Beibu Gulf is located in the northwestern part of the South China Sea and comprises the shallow water bay between China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Hainan Island, Leizhou Peninsula, and Vietnam. It lies in a tropical coastal landscape where the climate is humid and warm, and is classified as a northern tropical monsoon climate. The gulf is rich in ecological types and diverse in species. It is an important land and sea ecological barrier at the southern tip of China, and also an important global biodiversity hot spot. It is one of the key landscapes in the Country Programme Strategy of the GEF Small Grants Programme (SGP). Mangroves in Beibu Gulf are widely distributed, making it one of three major distribution areas for mangroves in China. It is also an important ecological zone for seagrass beds, coral reefs, and coastal wetlands.

1.2 Problem Analysis

Despite its ecological richness and diversity, Beibu Gulf has been faced with exploitation of its ecological resources and culture over the past 20 years alongside rapid development. Coastal erosion, sedimentation, pollution, degradation and reduction of wetlands in the intertidal zone, and decline in biodiversity are the main challenges faced by the region.

The cultivated land along the Beibu Gulf coast is fragmented. The proportion of agricultural income of villagers is low, while the proportion of fishing income is relatively high. Before the development of tourism, the main source of income for the locals was fishing, which was supplemented by agriculture. However, due to the deterioration of the marine ecological environment, fishery resources have been severely depleted. Income from fishing is at present much lower than it was previously. Some fishermen use electric trawls and other methods that destroy microorganisms in the ocean and seriously harm the ecological balance, worsening the situation.

Overfishing not only threatens the survival of Chinese white dolphins by affecting the food chain, but also seriously affects the livelihoods of local people who rely on fishing and tourism. Enclosed tideland cultivation has encroached on mangroves along the coast, affecting species in the intertidal zone and shallow sea fish, which has directly reduced the types and quantities of species that Chinese white dolphins prey on. As a result, the dolphins’ range and movement patterns have gradually narrowed, and biodiversity and ecological functions have been lost. This has directly affected the marine ecology in which this wild and endangered species lives, as well as the diversity of income sources of the fishermen who have lived here for generations. According to local villagers, the population of white dolphins was relatively large in the past, and there has been a recent trend of decline. Most of the residents support the protection of white dolphins and believe that the presence of white dolphins indicates a healthy natural environment.

The recent urbanisation of coastal areas and the industrialisation of fisheries has brought challenges to traditional fishing communities. As offshore fishery resources continued to be depleted, traditional fishing communities face a decline. These communities also face various other challenges, including population ageing, few employment opportunities, serious hollowing of rural areas, and low awareness of environmental protection and planning among fishermen. Thus, there is an urgent need to improve their village landscapes (Wang et al. 2018).

Because of its rich fishery resources, Sanniang Bay, which lies in Beibu Gulf, is home to Endangered, Threatened, and Protected (ETP) species, including the Chinese white dolphin (Sousa chinensis), horseshoe crabs (Tachypleus tridentatus and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda), and mangroves. The Chinese white dolphin is one of the species of wildlife protected at the national level in China, together with the dugong. Chinese white dolphins are listed as a species threatened with extinction in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES 2022), and were also listed as a vulnerable species in the IUCN Red List of threatened species in 2015 (Jefferson et al. 2017; Laurie et al. 2019).

In 2003, Sanniang Bay Village was designated as the Sanniang Bay Tourism Scenic Area by the Qinzhou municipal government. While some villagers have gained profit from tourism development, fishermen have faced a dilemma over livelihood transformation. Overfishing not only threatens the survival of dolphins, but also seriously affects the subsistence livelihood of locals.

The zoning of the proposed Sanniang Bay Chinese White Dolphin Nature Reserve and tourism development have created a conflict between conservation and development, making it a great challenge to balance the two. Many scientific research institutions in the area have already conducted a large number of scientific surveys and developed systematic conservation measures, accumulating a wealth of scientific data. But there has been insufficient communication with the villagers, who have little understanding of scientific conservation. Moreover, these assessments involved very limited participation from villagers. Likewise, government agencies are very familiar with the concept of “balancing environmental protection and sustainable utilisation of resources”, but have limited knowledge of communitybased conservation of natural resources in Indigenous Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs). In November 2012, the 18th Communist Party of China National Congress for the first time stressed the “high priority to making ecological progress and incorporate it into all aspects”. Ever since, the concept of “ecological civilisation” and environmental protection have been promoted in an accelerated manner. China’s policy shift to preserve ecology and the environment calls for conceptual and practical change to value a biodiversity-friendly fishery system. Hence, recognition of the importance of community participation in protecting marine resources is definitely needed by both scientists and government agencies.

1.3 Objectives and Rationale

According to the IUCN’s definition, Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs) are “natural and/or modified ecosystems, containing significant biodiversity values, ecological benefits and cultural values, voluntarily conserved by indigenous peoples and local communities, through customary laws or other effective means” (Kothari et al. 2012, p. 155). Community participation has always been the cornerstone of community development, environmental protection, and sustainable ecotourism development.

This case study highlights an interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder participatory approach to exploring a community-based conservation mechanism. The study aims to analyse the processes and outcomes of a pilot initiative aimed at the protection and sustainable development of fishing communities in the Beibu Gulf that took place for the period from January 2020 to June 2022. Demonstrating how the community’s actions with multi-stakeholder involvement can be collectively developed to build a collaborative network for capacity building, the study shows how the initiative engaged in awareness raising on marine resource conservation by introducing a community-based landscape approach.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study Site

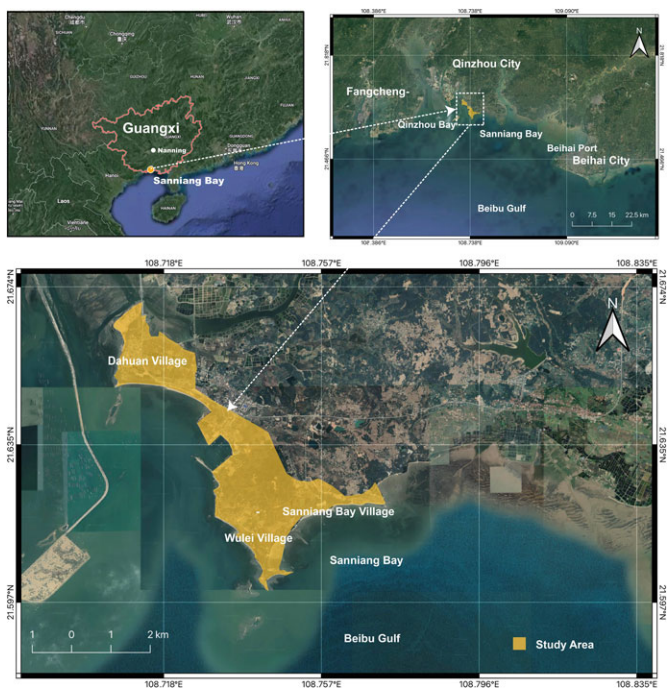

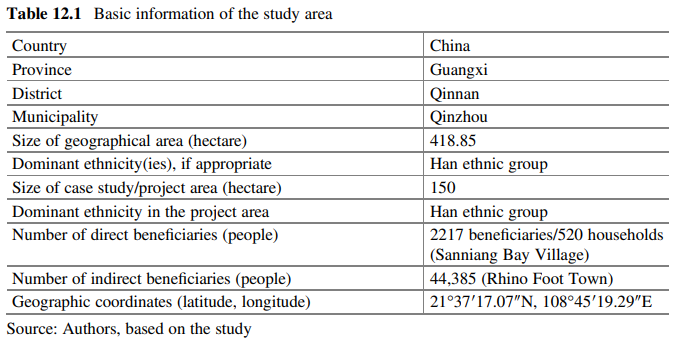

The pilot site is located in Qinzhou City on Sanniang Bay, which is defined as a restricted redline area of concentrated distribution of Chinese white dolphins in the “Guangxi Marine Ecological Red Line Demarcation Plan” (Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of Oceanic Administration 2018). The target sea area is composed of the Chinese White Dolphin Nature Reserve in the Qinzhou City of Guangxi Province, namely the sea area of Sanniang Bay and the estuary of Dafeng and Nanliu rivers in the Beibu Gulf, east to 108°47′49.20″ and west to 108°52′18.37″, north to 21°36′16.56″ and south to 21°31′11.72″ (Fig. 12.1). Sanniang Bay Village is under the jurisdiction of Rhino Foot Town, and consists of five villager groups with a total population of 2217 (Table 12.1). The Sanniang Bay is home to ETP species, including the Chinese white dolphin, horseshoe crabs, and mangroves.

According to information from the Sanniang Bay Tourism Management Zone Committee in 2019, the Sanniang Bay Village has a total area of 150 ha, of which 121 ha is slope land, and 2.5 km of coastline. The whole village lies within the Sanniang Bay Tourism Scenic Area. The villagers’ livelihoods are dominated by marine fishing and supplemented by tourism and agriculture. There are 185 large and small motorised fishing boats. The fishermen’s income depends on fish resources. During the fishing season, the daily income is not less than 300 CNY (equivalent to approximately USD44) per fisherman per day. Those villagers who do not have fishing boats work as sailors for those who do.

In 2003, Qinzhou City developed the Sanniang Bay Tourism Scenic Area. Consequently, villagers invested in the construction of restaurants and petty stores. Later, inns, retail stores, and tour guides joined to gradually form a service industry. In the village as a whole, about 60–70 people are engaged in the service industry, including catering, accommodation, sale of souvenirs, and white dolphin sightseeing services. Sanniang Bay Village won the award as the “most beautiful fishing village” in February 2018 by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs.

2.2Participatory Research Approach

Many conservation agencies along the Beibu Gulf coast focus on ETP species protection. However, fishing activities affect these protected species. To seek a sustainable solution, researchers initiated a pilot project to explore a communitybased mechanism for balancing the habitat protection and development of fishing communities, employing an interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder participatory approach.

2.3 Stakeholder Roles

The Farmers’ Seed Network (FSN) was founded in 2013 in Guangxi, established on the basis of participatory action research conducted by multiple institutes including the Center for Chinese Agricultural Policy of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and the Maize Research Institute of the Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Southwest China. FSN is a pioneering organisation in applying participatory research methods to examine agrobiodiversity and natural resource management in China.

In October 2018, FSN was officially registered as a non-governmental organisation in Nanning, Guangxi. As a non-profit social organisation, FSN has worked in over 40 rural communities in 10 provinces across the country to preserve plant genetic resources, support community-based seed conservation and sustainable utilisation, and facilitate productive collaborations between farmers and plant scientists for strengthening farmers’ seed systems, improving farmers’ livelihoods, enhancing farmers’ dignity, and promoting national seed security.

Based on participatory research experience accumulated in the field of natural resource management, FSN initiated its first coastal participatory research to promote ICCAs in Sanniang Bay Village in 2019. This research is jointly supported by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) Small Grants Programme of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Sowing Diversity = Harvesting Security (SD = HS) project of Oxfam Novib. The SD = HS project aims to support indigenous peoples and smallholder farmers in gaining the capacity to access, develop, and use plant genetic resources to improve their food and nutrition security under the conditions of climate change.

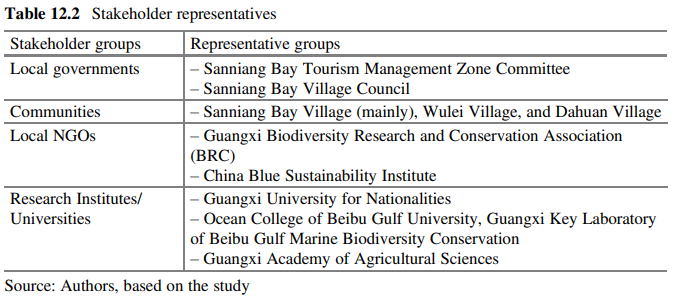

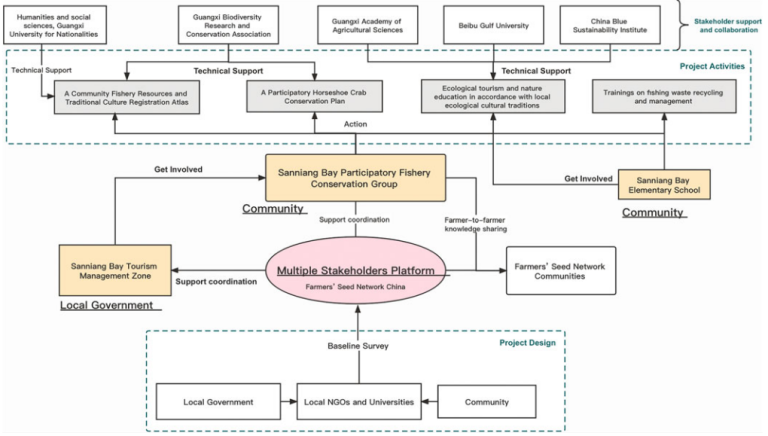

Building on the different roles of local communities, scientists, and NGOs in biodiversity conservation and utilisation (Table 12.2), FSN facilitates collaboration and cooperation between local communities, scientific communities, social organisations, and local governments (Fig. 12.2).

3 Description of Activities and Results

3.1 Villager Participatory Fishery Conservation Group

To gather baseline data and ensure that we address the actual needs of the community, we carried out a series of surveys and community engagement activities, including household surveys, key informant interviews, and group discussions. This process helped local participants and the project team to assess and reach a consensus on prioritised actions. The villagers proposed to use the community flexible fund provided by the project to support the establishment of a conservation group and provide a monthly labour subsidy of 400 CNY (equivalent to approximately USD58) per person for the villagers who patrol the beach every day.

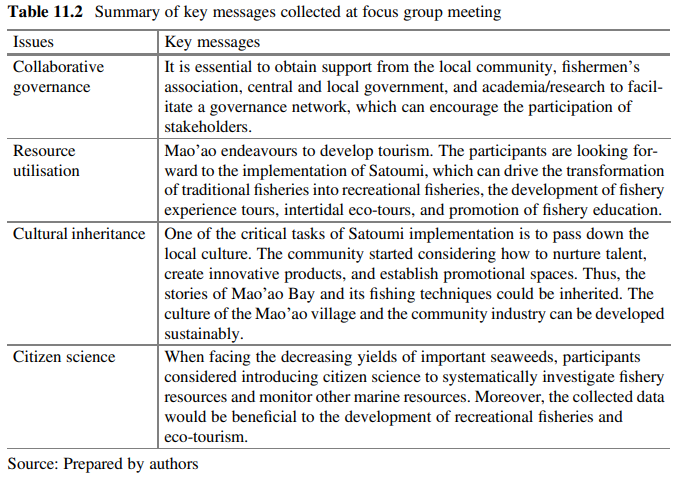

The questionnaire surveys were conducted for the community from July to September 2020. A total of 33 locals participated. The collected data included socio-economic background information for persons from Sanniang Bay Village, Wulei Village, and Dahuan Village. The first round of the survey asked mainly about the status and changes in fisheries and the marine environment of the community. The second pre-survey was conducted through key informant interviews with the elders, focusing on the processes of the village development as well as the fishermen’s transition from a collective economy (before the Reform and Opening-up in 1978) to the individual one. We also conducted focus-group interviews and community consultations between March and September 2021 to ascertain the perspectives of multiple stakeholders. Based on the above two rounds of baseline surveys and local research institutions’ findings, the FSN project team realised that the Sanniang Bay Village lacks a community group. Organising a community-based participatory group would allow for the integration of community needs and conservation wants into planning and implementation.

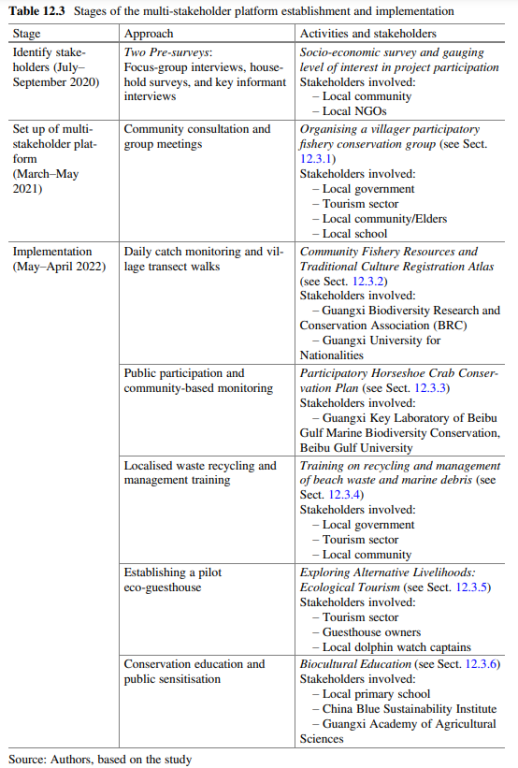

After several rounds of interdisciplinary research team visits and continuous surveys, the project team identified several key persons willing to participate, and the Sanniang Bay Participatory Fishery Conservation Group was organised. The group consisted of ten core members, including the director of the Sanniang Bay Village Council, the principal and a young teacher of Sanniang Bay Primary School, fishermen, guesthouse owners, and local dolphin watch captains (Table 12.3).

Through monthly or bimonthly meetings, the project team invited researchers and social organisation staff to brief core members on ongoing research findings. We interpreted protection measures in the context of local practices and supported the villagers’ action plans using the community flexible fund. Occasionally, we invited members to attend national workshops to engage in exchange with and learn about other successful local experiences in sustaining biodiversity and food systems in community-managed landscapes.

3.2 Community Fishery Resources and Traditional Culture Registration Atlas

In the past, the traditional fishing method used single-layer nets, which allowed smaller fish to escape. Recently, due to the development of pelagic fishery and fishing technology, single-layer nets have been transformed into three-layer nets to catch more fish. In response to increasing market demand, large fishing boats around Beibu Gulf are using high-density nets and other non-sustainable methods, gradually destroying the balance of marine ecological resources.

The local villagers of Sanniang Bay are still engaged in the traditional ecological fishing method. The majority of the fishermen in Sanniang Bay own family-run “husband and wife boats”. Typically, couples head out to sea for fishing on small wooden fishing boats, sailing out in the morning and returning in the late afternoon (Fig. 12.3). Based on the pre-survey mentioned above, local fishermen have all noticed a decline in the types and quantities of local offshore catches.

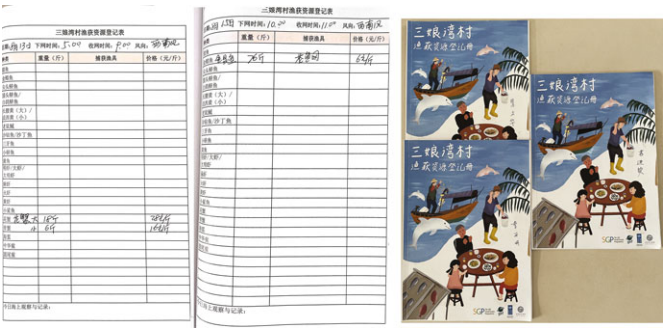

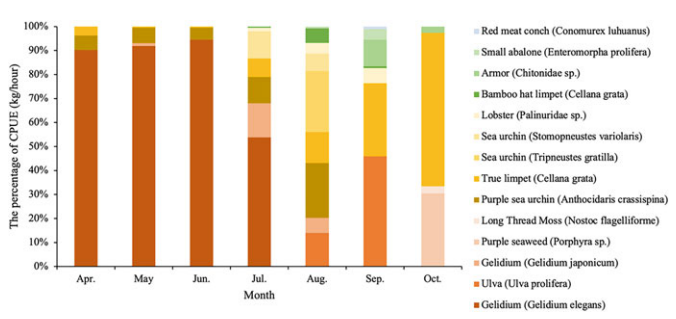

In collaboration with the Guangxi Biodiversity Research and Conservation Association (BRC), a local NGO in Nanning, Guangxi, the project team benchmarked the Beibu Gulf marine species to generate a Sanniang Bay community fishery resources and traditional culture registration atlas and created a localised Daily Catch Monitoring Form for the participatory fishery conservation group (Fig. 12.4). The form was used by three group members to monitor their daily catches. We started with three fishing boats in an attempt to keep year-round records of fish species caught, weight, landed price obtained, and fishing methods used. Long-term monitoring data can show changes in common catch and market price fluctuations, which could help in further exploration of marine ecology and the fishermen’s livelihoods.

To strengthen the connection between scientific knowledge and traditional practices, the project team carried out exchanges and cooperation with the Guangxi University for Nationalities and Beibu Gulf University to study and document local traditional knowledge in natural resources management.

3.2 Capacity Building

3.2.1 Surveys on Fishing Culture and Documentation of Traditional Knowledge

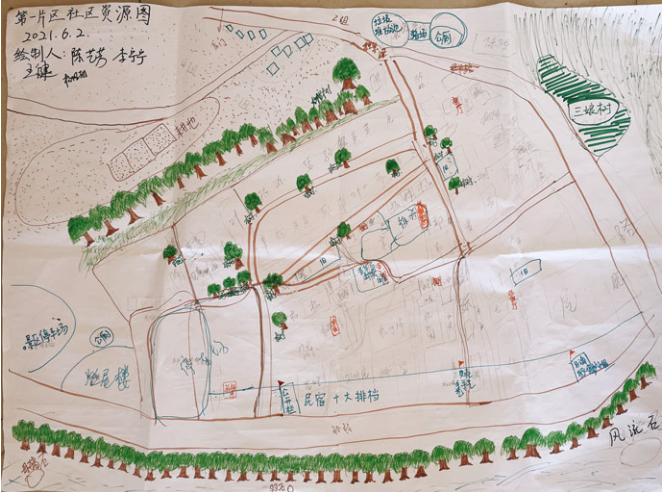

In May 2021, participatory methods, such as group meetings and transect walks, were utilised to invite villagers, village cadres, and the Sanniang Bay Scenic Area Management Committee members to map out the community’s natural and cultural resources (Fig. 12.5). These activities enabled the villagers to rethink and reconnect to the fishing village’s value. To ascertain the perspectives of different stakeholders, the project team brought together the Sanniang Bay Scenic Area Management Committee, Sanniang Bay Village Council, fishermen, and guesthouse owners to illustrate the natural and social resources of Sanniang Bay. The process identified many local tangible and intangible cultural properties, ranging from historical buildings and dwellings to religious beliefs, family relations, handicrafts, folklore, and lifestyles. Results demonstrate how traditional ecological knowledge is embedded in the village.

Meanwhile, the project team also established cooperation with an anthropological research team at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Guangxi University for Nationalities to systematically study and analyse the local cultural context. This collaboration has supported the community’s cultural and historical documentation and the formation of a solid foundation for the development of culturally appropriate ecotourism. The Sanniang Bay Scenic Area Management Committee also realised that aside from attracting tourists with the Chinese white dolphins, the development of the scenic area requires linkages with village culture. The fishermen and the sea are the heart and soul of the fishing culture. The sustainability of Sanniang Bay Village relies upon the inheritance of cultural heritage, honouring the harmony between humans and nature.

3.3 Participatory Horseshoe Crab Conservation Plan

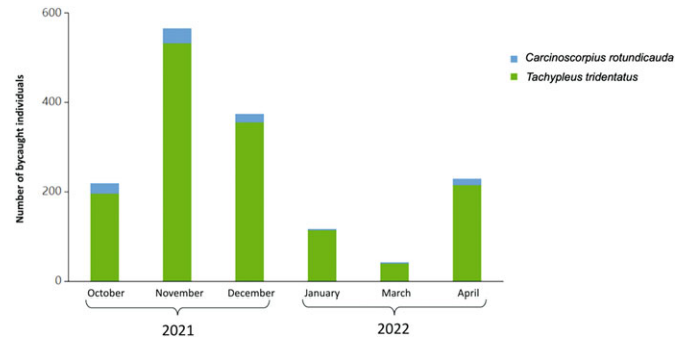

Following the establishment of the Sanniang Bay Participatory Fishery Conservation Group, members raised several issues involving ETP species and local ecology protection. In addition to being the main habitat of the Chinese white dolphin, Sanniang Bay is also home to mangrove horseshoe crabs (Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda) and Chinese horseshoe crabs (Tachypleus tridentatus), both listed as Class II protected species (Laurie et al. 2019). On September 8, 2021, the community group formulated an initiative called the “Send Horseshoe Crabs Home”. Five members rescue horseshoe crabs that have been accidentally caught in fishing nets and record their size and numbers daily (Fig. 12.6).

The record-keeping template was designed with help of a local research partner, Ocean College of Beibu Gulf University. Fishermen keep records of the width and number of horseshoe crabs during their daily work. Data obtained were provided to the Guangxi Key Laboratory of Beibu Gulf Marine Biodiversity Conservation to study the landing pathways of the horseshoe crabs (Fig. 12.7). This action is one in which local villagers can easily participate. The community group is planning to organise school children to join this initiative.

3.4 Training on Recycling and Management of Beach Waste and Marine Debris

According to the Sanniang Bay Tourism Management Zone Committee, the number of visitors to the bay has increased since entrance fees were waived in November 2020, and so has the amount of garbage. The management committee arranges garbage trucks and sanitation workers to clean the garbage drop-off sites twice a day during busy seasons.

Every year, from April to November, the monsoons affect the sea, and southwest winds blow garbage ashore. The beaches are often covered with household and marine garbage, which can be roughly separated into seashells, branches, leaves, plastic bottles, glass bottles, marine plastic, and nets. In the 1960s, local organic garbage such as seashells, with high calcium content, was crushed to feed chickens and ducks.

The management of marine debris must be performed as a continuous task to avoid garbage flowing back into the sea. Developing a circular economy by reusing sea waste is a possible solution. While it is important to deal with marine waste that has already been produced, it is even more critical to reduce marine pollution. Waste reduction and raising awareness on recycling are key elements of successful protection and management of marine ecosystems and their associated communities.

To bring localised waste recycling and management training to Sanniang Bay, the project team produced a short film called “Where the Trash Goes”. This video documented the entire garbage collection, transfer, and disposal process in Sanniang Bay and the designated waste disposal facility. The film was shown to fifth graders at Sanniang Bay Primary School.

The project team also invited village council members to clean up the beach before sunrise. Through garbage classification and weighing of the debris, we saw how much hazardous and non-hazardous waste was on the beach and the surrounding village areas.

Working with the primary school, local artist Ba Nong and school kids turned the garbage debris collected from the mangrove forest into musical instruments and a giant “X” to serve as a stage background. An “X” plastic concert was held with music that incorporated traditional elements and brought the tradition to life, expressing children’s belief in safeguarding the blue ocean. The children’s performance at the beach attracted many tourists, who came to Sanniang Bay (Fig. 12.8).

3.5 Exploring Alternative Livelihoods: Ecological Tourism

Since the Scanning Bay Tourism Scenic Area was set up in 2003, it has benefited the community economically. Today, many tourists visit Sanniang Bay to see the Chinese white dolphins, without paying much attention to the fishers’ lifestyle and village culture. Ecotourism has received much attention in recent years. We believe that the initial development of ecotourism must incorporate knowledge on local ecological resources and respect for nature’s fragile equilibrium. Local villagers with knowledge of local flora and fauna, traditional culture, and values should be incorporated and consulted in the ecotourism planning and design stage. Doing so would not only reduce the impact of tourism on the natural ecology, but also increase a connection with local life and culture. Ecotourism can be seen as a tool to strengthen sustainable tourism because it emphasises sustainable tourism principles (Salman et al. 2020).

We promoted an environmentally friendly management model in local guesthouses. After participating in the community cultural documentation and species monitoring activities mentioned above, one of the group’s guesthouse owners took the initiative to create an ecologically friendly service model, including: serving local ecological vegetables and fish caught by sustainable methods; reducing non-recyclable waste; and promoting friendly and non-disturbing dolphin-watching boats. In the near future, we plan to customise a local tour guide training programme. This will provide tourists coming to Sanniang Bay with a more in-depth and responsible travel experience. Concurrently, this programme aims to motivate villagers to learn more about the history and biocultural values of their village.

3.6 Biocultural Education

Sanniang Bay Tourist Scenic Area is targeted for the joint development of marine recreation and marine environmental protection. In addition to educating tourists on the concept of marine protection, residents in the community conservation areas also need courses on ecological conservation and management. According to the pre-survey and consultation with local schools, there is a lack of curriculum and educational resources based on local socio-ecological knowledge.

As needed, we invited marine biologists and nature art teachers to bring biocultural education and science popularisation classes into Sanniang Bay Primary School between March and September 2021. In the meantime, the China Blue Sustainability Institute launched a marine science education programme in the community, covering marine biodiversity, species conservation, and sustainable fisheries concepts.

Responding to the school’s needs, we designed a series of activities for local children. In March 2021, we launched a reading room at the primary school. This reading room stocks more than 100 picture books and books on marine environmental protection. During the book shopping process, we realised there are very few marine conservation books targeting coastal village children in China. Therefore, we supported local teachers to develop a customised fishing culture curriculum, while inviting village elders to be lecturers. Meanwhile, we facilitated food education for children, setting up an eco-friendly vegetable garden and food education class at school. The school garden was popular among the students and teachers. In addition to local vegetable varieties, other community partners from the Farmers’ Seed Network and the Academy of Agricultural Sciences provided indigenous seeds adapted to the Guangxi region (Fig. 12.9). To make children cherish and care for the ocean around them, we also supported the formation of a “Sea Song Squad”, with six children collecting local fishing songs, stories, and folklore.

4 Lessons Learned

After a series of explorations, a multi-stakeholder platform was established to improve coastal ecosystem restoration and sustainable livelihoods in Sanniang Bay. The initiative integrated scientific monitoring and baseline data collection into local fishermen’s daily practices, as well as supported villagers to establish a participatory data collection mechanism and build consensus on conservation. Our findings are mainly reflected in the following areas:

- To raise adults’ awareness of ecological conservation, an effective way is to work with primary school students, by setting up an eco-friendly vegetable garden, launching a marine-friendly reading room, and organising a beach clean-up concert.

- To explore alternative livelihoods for coastal communities, a feasible practice is to pilot community-led ecotourism combining community-guided tour services rooted in location-specific cultural elements, and a plastic-free, seed-to-table eco-guesthouse.

- To mobilise individuals’ and community participation, the optimal path is to facilitate exchange visits.

- To establish an integrated beach waste management model in the Beibu Gulf, marine plastic debris should be monitored and sampled at a network of sites during the southwest monsoon season.

One of the highlights of this study’s findings lies in the active participation of school children. The launch of the vegetable garden was a big hit among children, who were encouraged to grow, harvest, and cook their own food and share it with their families. This activity has enhanced the acceptance of the project team among the villagers. Another highlight is guaranteeing the community’s participation with help of NGOs and scientists, since they are the ones who could provide accurate information on the social and environmental situation of the seascape. In particular, local NGOs played the intermediary role in capacity building, networking, and linkages for external support and exchange. Multiple-stakeholder platforms and networks with integrated approaches are crucial for supporting community-based conservation and development, as different stakeholders, including NGOs, scientists, civil society groups, enterprises, etc., can provide different information and support that communities need in the process at different times and in various situations. The experiences of Sanniang Bay Village are being scaled out to the two neighbouring communities of Wulei and Dahuan, as well as to Weizhou Island and Xia Village on the Beibu Gulf. The aim is to build a network to exchange lessons learned on biodiversity conservation and community development for further exploration of seascape-based ICCAs.

5 Conclusion

This case study especially highlights the significant role of community and smallholder fishermen in collaboration with multiple stakeholders on seascape restoration and community development. Despite facing challenges from biodiversity loss, industrial fisheries, and ocean degradation, the community strengthened their leadership and collaboration with social organisations, research institutions, and local governments via localised and culturally appropriate training, school education, and exchange visits. The Sanniang Bay fishing community’s awareness and actions on conserving endangered species, including Chinese white dolphins, horseshoe crabs, and mangroves, and engaging in sustainable tourism and fisheries, were promoted via these initiatives.

We emphasise the importance of protecting the marine environment and coastal biodiversity, in addition to the protection of Chinese white dolphins and horseshoe crabs. We stress the key roles of communities and policy recognition for supporting community participation. We have illustrated community-based conservation as the main approach adopted by the case for involving multiple stakeholders in achieving sustainable development and financial security.

References

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, CITES (2022) Appendices I, II and III. https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php. Accessed 15 Aug 2022

Google (2021) Google maps of Qinzhou City, Guangxi, China. https://goo.gl/maps/asvqW8sr7Dk6NGAc6. Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of Oceanic Administration (2018) The marine ecological red line was demarcated. http://hyj.gxzf.gov.cn/zwgk_66846/xxgk/fdzdgknr/bmwj/t3445428.shtml. Accessed 11 Nov 2021

Jefferson TA, Smith BD, Braulik GT, Perrin W (2017) Sousa chinensis (errata version published in 2018). The IUCN red list of threatened species 2017: e.T82031425A123794774. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-.RLTS.T82031425A50372332.en. Accessed 15 Aug 2022

Kothari A, Corrigan C, Jonas H, Neumann A, Shrumm H (eds) (2012) Recognising and supporting territories and areas conserved by Indigenous peoples and local communities: global overview and national case studies. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, ICCA Consortium, Kalpavriksh, and Natural Justice, Montreal. Technical Series no 64, 160 pp. https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-64-en.pdf

Laurie K, Chen C-P, Cheung SG, Do V, Hsieh H, John A, Mohamad F, Seino S, Nishida S, Shin P, Yang M (2019) Tachypleus tridentatus (errata version published in 2019). The IUCN red list of threatened species 2019: e.T21309A149768986. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T21309A149768986.en. Accessed 15 Aug 2022

Salman A, Jaafar M, Mohamad D (2020) A comprehensive review of the role of Ecotourism in sustainable tourism development. e-Rev Tour Res 18(2):215–233

Wang X, Wan R, Zhu Y (2018) Problems and countermeasures of China’s fishery community development. Modern Agric Sci Technol 8:274–277

Note

The opinions expressed in this chapter are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNU-IAS, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent.

Open Access This chapter is licenced under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ igo/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to UNU-IAS, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. If you remix, transform, or build upon this book or a part thereof, you must distribute your contributions under the same licence as the original. The use of the UNU-IAS name and logo, shall be subject to a separate written licence agreement between UNU-IAS and the user and is not authorised as part of this CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO licence. Note that the link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the licence.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from

the copyright holder.