Linking biodiversity conservation, green production and local mutual trust in a SEPL(S)

04.02.2021

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION

Taiwan Landscape Environment Association (TLEA)

DATE OF SUBMISSION

04/02/2021

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Chinese Taipei

KEYWORDS

SEPLs, biodiversity, eco-farming, green products, Participatory Guarantee System, sustainable rural development

AUTHOR(S)

Chen-Fa Wu 1, Chen Yang Lee 2, Ling-Tsen Chen 2, Chih-Cheng Weng 3, Choa-Hung Chang 3, Xin-Feng Hsieh4, Hao-Yun Chuang2, Ming Cheng Chen 2, Chun-Hsien Lai5, and Szu-Hung Chen 6*

1 Department of Horticulture of National Chung Hsing University (NCHU), No.145, Xinda Road, South District, Taichung City 402, ROC (Chinese Taipei)

2 Soil and Water Conservation Bureau (SWCB), No.6, Guanghua Road, Nantou City 540, ROC (Chinese Taipei)

3 SWCB Taichung Branch, No.22, Yangming Street, Fengyuan District, Taichung City 420, ROC (Chinese Taipei)

4 Sanyi Township Farmers’ Association-Liyutan Branch, No. 57-1, Liyu Village, Sanyi Township, Miaoli County 367, ROC (Chinese Taipei)

5 Taiwan Landscape Environment Association (TLEA), 10F, No. 118, Mingcheng 2nd Road, Sanmin District, Kaohsiung City 80794, ROC (Chinese Taipei)

6 International Master Program of Agriculture, NCHU, No.145, Xinda Road, South District, Taichung City 402, ROC (Chinese Taipei)

* Corresponding: Szu-Hung Chen (vickey@dragon.nchu.edu.tw)

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Abstract

Climate extremes (e.g., draught) and insufficient water resources may be common challenges that agriculture production is facing in the world. Unlike of that, Liyu community is blessed with natural resources, including clean water, stable irrigation supply, and fertile soil. It is located downstream of the Liyutan reservoir surrounding by farmlands, primary and secondary forests, which forms the SEPL in the so-called “Low Elevation Mountain Ecosystem” of Taiwan (i.e., attitude lower below 800 m). In addition, there is less human activity and industrial development, leading to lower probability of interference upon wildlife. Therefore, the Liyu community retains richer biodiversity. However, before 2013, most residents practiced conventional farming that is harmful to both human and environments. Since then, community people began to understand the interaction between ecosystem and human health and realize the necessity of environmental ethical implementation that is able to maintain the equilibrium.

In recent years, governmental authorities of Taiwan (e.g., Council of Agriculture, COA) actively promote the SDGs and apply practical measures to rehabilitate farmland ecosystems. However, few systematic approaches have been well addressed. The purpose of this study is to provide scientific evidence of farming practices to enhance both human and ecosystem health in rural and demonstrate a local-scale implication for policy makers. In order to achieve the goal which can be a win-win situation for both human and the entire SPELs, corresponding objectives are:

- to restore SPELS with eco-friendly farming;

- to support biodiversity by implementing habitat restoration and eco-farming practices;

- to integrate traditional farming wisdom and modern technology related to pest biocontrol and resilience;

- to increase local incomes and economics by green production chain.

Long-term ecological monitoring provides insight of the benefits for organic/eco-friendly farming practices on biodiversity conservation. Results indicate that organic/eco-farming rice fields support the higher species richness and abundance in various taxonomic groups (e.g., aquatic species). It also represents significant difference on species richness between paddy fields in eco-friendly farming and others in conventional practice. Regarding the SEPLS management, farmers make use of excess water resources in rice paddy and then develop a transformative way to control rice blast disease, literally, turning a disadvantage to a useful mean. Biological pest control experiment attempts to discover the mechanisms of natural resource management integrating traditional wisdom and culture, particularly, emphasis on controlling Golden Apple Snail (GAS) population which is threating the food production and local incomes. Results show that food waste and several natural fruits can serve as effective baits when setting up traps to control GAS spread during the early stage of crop growing seasons. Farmers also implement other practices that can benefit crop production and biodiversity mutually, such as using Azolla as a green manure in rice cultivation, no herbicide spray, and creation of ecological ponds as biological refuge during non-growing time (i.e., rice fields would be left dried). Moreover, Liyu community promotes responsible production and consumption (PGS), develops green production chain that provides economic drivers to pursue sustainability.

Rationale

Starting from 2013, residents began to learn about the interlinkages among biodiversity, responsible production and human health; then have been practiced organic/eco-friendly farming (e.g., reduced use of agrochemicals) to protect farmland ecosystem from ongoing habitat loss and degradation. Besides that, the organic (or eco-growing) rice can not only ensure responsible and sustainable production but also enhance human physical health than conventional farming. Thus, To respond to the challenges mentioned above, the Liyu community set its vision as “Linking biodiversity conservation, green production, and local mutual trust in a SEPL” and commits to seek, foster and implement actions that can achieve sustainable future. Particularly, the goal is to build a production landscape with the balance among social, ecological, economic aspects through consensus building among farmers, responsible and ethical use of resources in the SEPL (e.g., land), promoting eco-friendly farming, implementing biodiversity and habitat conservation, and developing green production chains.

Objectives

Referring to the goal above, Taiwan Landscape Environment Association (TLEA), Liyu Community, National Chung Hsing University (NCHU) and the Soil and Water Conservation Bureau (SWCB), a government agency, work collaboratively and implement numerous actions (activities), aiming to achieve a vision of co-prosperity, a win-win situation for both human and the entire SPELs of Liyu. Corresponding objectives are:

- to restore SPELS with organic and eco-farming practices;

- to maintaining biodiversity by implementing habitat restoration and eco-farming practices;

- to pass on local farming wisdom related to pest biocontrol and climate smart agriculture;

- to increase local incomes and economics by promoting the green production chain.

Activities and/or practices employed

1. Efforts to practice eco-friendly farming to reduce environmental impact and hazards

In light of the changes in the ecological environment of the farmland and impacts on biodiversity, farmers have begun to experiment with alternative farming methods. Since 2013, the community has taken part in the rural regeneration program promoted by the SWCB. Through a 92-hour training course, local residents and farmers were able to increase their awareness about community development and friendly agriculture. The community also received guidance from the Tse-Xin Organic Agriculture Foundation (TOAF), an NGO that promotes eco-friendly farming, to implement cultivation methods that conform to green conservation practice, which include:

- Green conservation standards must be continuously adopted in agricultural production practices to ensure that the goals of the green conservation production model are effectively implemented.

- The construction of enclosed production areas in fields is discouraged for ecological and conservation reasons.

- Farmers should choose appropriate farming and cultivation methods that adequately protect the soil and reduce erosion. To ensure suitable soil fertility and facilitate soil fertility management, farmland soil fertility management should be based on reports from agricultural research institutes, agricultural research and extension stations, or qualified laboratories.

- Good soil management and water conservation measures should be implemented on agricultural land to ensure the sustainable use of soil and water resources.

- Materials and organisms that have been introduced to green conservation production should be carefully evaluated to avoid significant impact on existing organisms and the environment.

- Priority is given to species or varieties of crops with good environmental adaptability and resistance to pests and diseases. Farmers are encouraged to retain seeds and nutrient propagules to enhance species diversity.

- For disease management, farmers should either use management methods that inhibit the spread of pathogens and microorganisms or non-synthetic biological, plant, or mineral materials.

- Pest management could involve the introduction of predatory or parasitic natural enemies of pests and the creation of habitats for these natural enemies of pests, or the use of non-synthetic control methods such as baits, traps, and repellents.

- Weed management could involve mulching with fully biodegradable materials, soil preparation, livestock grazing, manual or mechanical weeding, plastic sheeting, or other using synthetic mulches (Figure 4).

In 2014, only one farming household was willing to adopt farming practices that comply with green conservation regulations. This number increased to 3 farming households in 2015 and currently, there are 8 such farming households.

(a)

(b)

Figure 4: (a) Weeds and rice coexist in eco-friendly farming fields; (b) Weeds growing on ridges are cut by hand without spraying any herbicide.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

2. Implementing organic/eco-farming practices in rice fields

In order to address the problem of excessive weeds and increase nitrogen fertility of paddy fields simultaneously, the Taichung District Agricultural Research and Extension Station (TDARES) performed an experiment that involved stocking rice fields with Azolla pinnata, a species of aquatic fern. Each plot was deposited approximately 50 to 65 kilograms of Azolla pinnata provenances. After 20 to 30 days, the water was covered with Azolla pinnata, which can effectively prevent the growth of weeds with an inhibition rate of over 85%. Evidently, Azolla pinnata suppresses weeds and enriches soil nitrogen fertility, which in turn increases rice production. Furthermore, the symbiosis of Azolla pinnata with Cyanobacteria comes with a process, namely nitrogen fixation by which atmospheric nitrogen is converted into ammonia (NH3) or related nitrogenous compounds in soil (Postgate, 1998), then becoming natural sources of nitrogen fertilizer that can benefit plants. Thus, when rice fields dry up and the Azolla pinnata dies naturally, it is plowed back into the soil, thereby turning into fertilizer as well.

Although there are numerous benefits to growing Azolla pinnata in rice fields, only a couple of farmers in Taiwan have adopted this application over the years (Liu, 2018). The main reason is that farmers need to set up a pond in or around their fields first in order to cultivate enough Azolla pinnata before it can be introduced into the rice field where it can serve as weed suppression and nitrogen fertilizer supplementation. Since most farmers in Taiwan own the area of lands less than 0.25 ha, they are not keen on using limited land resources to set up additional ponds for cultivation; as a result, the implementation was not effective. The Liyu Community’s farmlands have an abundant water supply. Side ditches are often dug for drainage (Figure 5), making them perfect breeding grounds for Azolla pinnata. Correspondingly, farmers there have been attempting to use Azolla pinnata since 2019.

(a)

(b)

Figure 5: Eco-farming fields have too abundant water and form puddles in low lying areas, making it impossible to grow rice; (b) Side ditches must be dug along the ridge for drainage

3. Maintaining biodiversity by implementing habitat restoration and creating in organic/eco-farming rice fields

Since 2014, Liyu has been gradually implementing organic and eco-farming methods, emphasizing the non-use of pesticides, chemical fertilizers, or other harmful methods to the environment and living organisms. Puddles in their fields have turned into habitats of mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis), Freshwater shrimp (Neocaridina denticulate), and Chinese spined loach (Cobitis sinensis). According results of field survey, a total of 14 wildlife habitats were identified. Additionally, the side ditches became habitats of the Paradise fish (Macropodus opercularis), Chinese spined loach, Günther’s frog, and broad-folded frog More importantly, field drying is necessary after harvests for sterilization. Since most of the water in the fields is drained, only the side ditches and springs have water remaining, which has become ecological refuge areas for organisms (Figure 5). During this period, instead of capturing these organisms, farmers should continue introducing water to maintain the minimum Ecological base flow that can enable the organisms to survive though the post-harvest season. In addition, Liyu’s farmers retain a 0.2-ha ratooning rice area as a foraging and roost ground of birds, so that they have a sufficient food source after harvesting.

Regarding to the future trend, important intents of site-based long-term ecological monitoring is not only to document changes in important biological properties of target ecosystem, but also to linking essential biodiversity variables and ecosystem integrity (Haase et al, 2018). In Liyu, there are 7 long-term ecological monitoring sites of aquatic organisms with various microhabitat conditions (Figure 6a). The No. 1 site presented the highest species richness. Aquatic environments of the No. 2 and No. 3 sites include irrigation or natural grass ditches (Figure 6b); hence, freshwater shrimp, freshwater prawn, pond loach (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) and Chinese softshell turtle were easily to be seen. The No 4 site was located at a related distant location away from the main route of human activities. Since fewer disturbances occur, a large population of female freshwater prawn was found here. It may imply that the No. 4 could be a major spawning ground for freshwater prawn. The No. 7 site was a spring-fed area, where the most tadpoles were found, and it could be an essential aquatic environment for amphibian reproduction and larvae growing.

Based on the survey results, farmers widen the side ditches between the No. 2 and No. 3 sites and then linked them to ecological corridors that serve as pathways for fish, shrimp, crabs, and aquatic insects. This action creates a constant water flow in the irrigation ditches and turns these ditches into post-harvest ecological refuges. Since the No. 7 site has low-lying, flooding area where rice barely grows (Figure 5a), so farmers dug a pond to provide a habitat for aquatic organisms during the dry season (Figure 7).

(a)

(b)

Figure 6: (a) Locations of 7 long-term ecological monitoring sites in the SEPL of Liyu; (b) The side ditch was widen and became a biological corridor

(a)

(b)

Figure 7: (a) on May 22nd, 2019, low-lying areas of rice fields were reconstructed and set up as ecological ponds; (b) plants coverage around the pond after 5-month succession

4. Biological pest control of the golden apple snail (GAS) based on local farming wisdom

Invasive species have always been a major threat native environments, biodiversity and ecosystems (Lodge, 1993). As one of invasive agricultural pests in many Asian countries of tropical and subtropical regions (Baker, 1998, Rawlings et al., 2007, Seuffert and Martín, 2009), the golden apple snail (GAS), also known as the channeled apple snail (Pomacea canaliculata), have brought great impacts on agriculture production due to its flexible adaptability, high rate in growth and reproduction (Cowie, 2002, Estebenet et al., 2006). In Taiwan, GAS is considered as a pest during the dibbling of rice seedling. In fields wherein conventional farming methods are practiced, the pesticides are often used to control population of channeled apple snails, ironically, killing fish and shrimp in rice paddies as well. In the Liyu’s fields, the damage caused by GAS is even more serious during the seedling stage due to the abundance of water and the implementation of organic/ eco-farming methods. However, one day farmers found out how the GAS rushed to grab paper mulberry leaves as falling into ditches. They were suddenly inspired and decided to plant paper mulberry trees, a native tree species of Taiwan, around puddles or low-lying areas. Afterward, farmers waited for the snails to gather before catching them, demonstrating a time-saving, effort-saving, cost-effective pest control method.

5. Rice blast control with excess water

According to the observation and analysis of the study sites, if the temperature between rice plants is too high, it could cause rice blast disease to spread. Therefore, it was necessary to find a way to lower the temperature effectively. The farmers and the Miaoli District Agricultural Research and Extension Station (MDARES) worked together to search solutions of this problem. First, when transplanting rice seedlings, the spacing between plants had to be increased by about 1.2 times the average, and each cluster of rice plants had to contain 3 to 5 fewer plants than average. This increases the ventilation space between the rice plants. The vegetative growth period occurs 30 days after rice transplanting. It is necessary to maintain a small amount of continuous water flow into the field to reduce both the water level and the rising temperature between plants during the summer. Likewise, the growing and reproduction period is between the 55th and 80th days after transplanting; it is also the period when crops are most prone to rice blast. In order to reduce the risk of disease propagation, a high water level should be maintained and input water should increase net flow, hence, being able to quickly carry accumulated heat away.

6. Establishing a cross-sectoral cooperation platform to develop green production chain and strengthen economic development

Approximately 1.1% of total farmland area in Taiwan is cultivating eco-farming and/or organic crops. A complete industry chain is necessary to support the development of this green industry. The Liyu Community has been practicing eco-farming and organic rice cultivation for 6 years, covering an area of 3.71 hectares with an annual rice production up to 18.5 tons. A “earmarked” post-harvesting process system, including rice harvesters, dryers, and rice mills were established and specifically used for organic and eco-farming crops to avoid contamination with conventional rice. The farmers jointly established a unified, registered brand called “Green Farmer (青稻夫),” a brand that sell eco-farming/organic rice harvested in the region (Figure 8). Having a unified brand can reduce time and labor costs, centralize resources of sales and marketing, as well as increase local products exposure to consumers.

(a)

(b)

Figure 8: (a) “Green Farmer (青稻夫)”, the Liyu community’s rice brand; (b) Increasing consumers’ recognition with the product through farming experience activities.

Results

1. Rice paddy fields of Liyu passed the organic farming certification and the pesticide residue-free inspection

In 2014, a farmer planted 0.0291 hectares of friendly fields and received the certified “Green Conservation Badge,” which encouraged other farmers to do the same. In 2018, a total of 8 farmers received the badge, leading to a total of 3.71 hectares of friendly fields. The farmers said that the purpose of eco-friendly or organic farming is “not to use chemical fertilizers so as to uphold a virtuous cycle of using land sustainably, maintaining biodiversity, and reducing pests and diseases” (Personal communication, translated by Chen, S.H). They also stated that “It is our great pleasure when we are able to eat with friends at ease and see different kinds of small animals returning our land” (Personal communication, translated by Chen, S.H).

The Taiwanese government passed the Organic Agriculture Promotion Act on May 30, 2018 in order to protect soil and water resources, the ecological environment, biodiversity, animal welfare, and consumer rights, as well as to promote an agriculture-friendly environment and the sustainable use of resources. The government subsequently formulated the regulations, inspection standards, and methods for practicing organic farming. In 2019, two farmers in the Liyu Community had 0.9426 hectares of rice fields certified. Their successes set a model for other local farmers regarding how to transform from natural growing or eco-farming methods to organic farming practice. It has guided eight other farmers advancing to organic farming practices that can benefit farmland ecosystems and environments more.

2. Planting Azolla pinnata in rice fields to reduce labor costs and increase economic benefits

Since the on-site springs bring water continuously, Liyu’s rice paddies require side ditches for draining excess water. Because water is available all year round, these areas are suitable to plant Azolla pinnata. In 2019, they started cultivating and introduced it into an adjacent organic paddy field (Figure 9). For fields adopting organic farming methods, Azolla pinnata is able to suppress weed growth and then reduces required time and labor of removing weeds by hand. With good management, up to 5 tons of Azolla pinnata per plot of land can release 7.5 kg of nitrogen after being plowed into the field, which is enough to supply 50% of the nitrogen fertilizer required for the next phase of rice growth. Additionally, rearing Azolla pinnata paddies could increase amount of soil organic matters, reduce soil compactness, increase the number of productive tillers, and then improve rice yield at least 5%. This is an important ecological cultivation technique for organic rice farmers in the Liyu Community and its use has been promoted to other farmers in the community.

(a)

(b)

Figure 9: (a) Propagation of Azolla pinnata in a nursery pond; (b) Using the field’s side ditches to cultivate Azolla pinnata

3. Effects of creating ecological corridors and biological refugia in organic and eco-farming fields

The Liyutan Reservoir serves as the water source of the organic fields. After the rice is harvested each year in November, the water supply from the reservoir is suspended and no water remains in the irrigation ditches. Instead, there are still water in small water ditches, side ditches, and areas in the field with rising groundwater, which become the primary hiding places and habitats for aquatic organisms. However, the shallow water depth in these areas makes organisms running into high risk of which die either due to high water temperatures or getting eaten by birds.

Because of this, areas in the field that have been experiencing rising groundwater for many years are not conducive for growing rice, as they have become natural reproduction grounds for the GAS. Therefore, farmers dug a 60-cm-deep hole in the area and built a 100 cm embankment covering a total area of approximately 75 square meters. Generally, the water depth is around 80 to 100 cm, with the main water source coming from the inflow of groundwater and irrigation ditches. Most organisms in the pool come from the middle of the irrigation ditch. The freshwater prawn and the paradise fish are the most common aquatic species that can be seen there.

According the field survey on May 25, 2019, an investigation held before the ecological pond creation, only 1 adult freshwater prawn was caught. The creating process was completed on July 29, 2019 and a survey was carried out about one month later on August 22, 2019, found 5 adult freshwater prawns. Subsequent surveys conducted on September 15, 2019 and May 6, 2020 found 15 adult freshwater prawns and 3 paradise fishes, and 19 freshwater prawns and 6 paradise fishes, respectively. These results demonstrate how a small-sized, semi-artificial pond can turn into suitable habitats for freshwater prawn and paradise fishes. Both species survive through the dry season lasting from December 2019 to January 2020 and maintained a steady population growth, which present a great advance for species conservation in a SEPL.

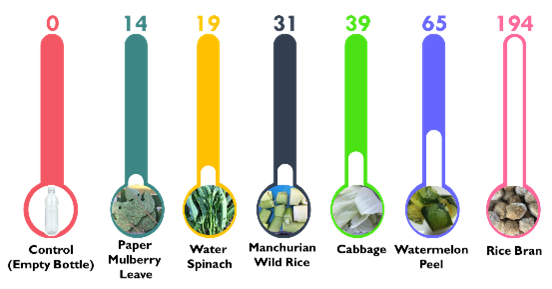

4. Biological control of GAS contributes to the conservation of aquatic organisms

In July 2019, Thai, Vietnamese, Indonesian, and Honduran students from the International Master Program of Agriculture (IMPA) of NCHU participated in Rural Up Program in Taiwan and start a long stay in Liyu (Figure 10a). They noticed the GAS issue in organic and eco-farming fields, specially causing serious harm to rice cultivation as their respective countries. After discussing with several stakeholders (e.g. farmland owner), the students proceeded to carry out an empirical experiment on understanding the foraging preference of channeled apple snails (i.e., GAS). The purpose is to find out what types of baits can catch more snails. Firstly, they used recycled 1-liter PET bottles to prepare “one-entry shrimp traps”, then filled traps with various baits and then placed them at an equidistant distance of 1 meter. Baits included paper mulberry leaves, cabbage (food waste), water spinach, Manchurian wild rice stem, rice bran, watermelon peel (food waste), and an empty bottle to serve as the controlled variable. The experiment was conducted in July, for 3 consecutive summer days. The results showed that rice bran was the most effective one, attracting 194 snails. It was followed by watermelon peel with 65 snails, cabbage with 39 snails, Manchurian wild rice stem with 31 snails, water spinach with 19 snails, paper mulberry leaves with 14 snails, and the controlled variable (empty bottle) with 0 snails (Figure 10b). Rice bran bait preparation involves mixing it, rolling it into a ball, and then roasting it with fire. This method costs materials (e.g. rice) and time. It is followed by watermelon peel in terms of effectiveness; however, watermelon peels are only available during the watermelon season. Although cabbage, Manchurian wild rice stem, water spinach, and paper mulberry leaves may not be the most effective bait, they can be easily collected from fields or local households. They are also cheap and can be grown all year round. Using these four types of leaves to catch snails, which is also in line with eco-farming methods, has become the most effective means of biological pest control in the Liyu Community and has been shared with other farmers, who practiced conventional farming.

(a)

(b)

Figure 10: (a) International students from IMPA of NCHU participating in the field survey of the GAS and other aquatic organisms; (b) Results of the experiment on catching the GAS.

5. Using running water to prevent rice blast and reduce harmful effects caused by pesticide use

The occurrence of rice blast can be linked to environment conditions. Frequent temperature fluctuations will reduce the crop’s resistance and makes it prone to be infected; high humidity can cause pathogenic fungus to produce spores and spore germination that then invades the rice tissue after germination, and further weakens the crop, resulting in an excess use of nitrogen fertilizer (Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute, COA. , 2020). The Liyu Community adopted methods such as reducing the number of rice plants in a single cluster, increasing the distance between rice clusters, controlling the flow of water into the field to maintain a stable temperature, and using Azolla pinnata, one type of green manure, as a source of supplemental nitrogen to reduce the use of chemical fertilizers. After four years of field experiments, the number of rice blast occurrences and the area of infected spots have been significantly decreased. In general, having too much water in a paddy field could be a constraint in rice farming. However, Liyu’s farmers and agricultural institutes work together develop a transformative way by using excess water to control rice blast disease, literally, turning a disadvantage to a useful mean. It not only reduces the use of pesticides but also mitigates its impacts on the farmland biodiversity.

6. Smallholders’ rice sales methods and their effectiveness

The sales channels for the Liyu Community’s rice include retail sales by the farmers themselves, participating in the Shan Shou Xian market operated by the SWCB, selling through the Leezen online store, and participating in farmers’ markets in other counties and cities. In this manner, they can sell their rice throughout the year. In terms of price, average rice price in Taiwan sells for about NTD 55 per kilogram; however, the organic and eco-farming rice produced in the Liyu’s SEPL costs NTD 130 per kilogram, which is 2.36 times higher. Because of the good income and incentives, farmers are willing to continue adopting organic and eco-farming practices

During rice dibbling or harvesting seasons, the community and the Tunghai University (THU) co-organize harvesting activities for the general public. Through these actives, students and urban consumers learn about knowledge and process of organic or eco-farming methods and can visit places of product origin, which, in effect, increases their trust in the farmers’ production. Furthermore, an enterprise subscription was initiated in collaboration with the NCHU. During each event, enterprises can purchase rice produced by approximately 0.1 hectares. Each purchase contributes to the sale of rice substantially, raises consumer awareness regarding the production area, enhances farmers’ confidence for future rice production, and increases the willingness of enterprises to repurchase.

Lessons learned

Farmers began to recognize the importance of biological and habitat conservation; then self-motivate to conduct field ecological and biological surveys regularly. Those who engaged in organic and eco- farming all grew up in the Liyu Community. During their childhood or teenage (around the 1960s), biodiversity in farmland was much more abundant, so they were quite familiar with original native species. After experiencing the devastating effects of the conventional farming era (from 1990 to 2012), several farmers started switching to practice eco-friendly and organic farming since 2013. After that, farmers were happy to find terrestrial and aquatic species gradually reappearing in their fields. Subsequently, it even motivated community members to record these organisms by photos systematically in conjunction with Butterfly Conservation Society of Taiwan and NCHU. Thus far, butterflies have been surveyed and documented for four consecutive years, while fish, shrimp, moths, and birds have been surveyed and documented for two consecutive years (Figure 11). This citizen science database can bring great contribution with various aspects, such as ecological education, habitat conservation, biological protection, eco-tourism, etc.

Since the community started a monthly, independent butterfly survey in 2015, around 42 surveys have been carried out so far. A total of 130 species of butterflies from 5 families have been documented, including 55 species from the family Nymphalidae, 22 species from the family Lycaenidae, 14 species from the family Pieridae, 18 species from the family Papilionidae, and 21 species from the family Hesperiidae. Speaking of the farmland production landscape, butterfly is not only an important pollinator, but also an indicator species of organic farmland (Figure 12). For example, male common Mormon (Papilio polytes), often travel to the organic fields, feeding on ground fluids in order to intake essential minerals such as sodium (Na). During mating, the male butterfly uses its spermatophore to transfer sodium into the female butterfly. Doing so can increases the fertility and life span of male butterflies as well as increase the total number of eggs fertilized by females. The host plants of Peacock butterfly (Aglais io) are usually weeds, such as Lindernia anagallis, Corydalis bungeana turcz., Hygrophila pogonocalyx, and Plantago asiatica, which grow in grassy ditches and ridges between fields. Adult butterflies are common foraging in rice-growing areas. Therefore, the application of organic and eco-farming practices in the Liyu Community is very important to protect the butterflies that use rice fields as their habitat.

Figure 11: The community members conduct independent, monthly butterfly surveys

Figure 12: Microhabitats and indicator species in the SEPL of the Liyu Community

Community residents actively participate in the long-term ecological monitoring in order to gain more knowledge species biological behavior, based on that, being able to determine rational habitat management strategy. After years of ecological surveys, the community has identified indicator species for each microhabitat in the SEPL (Figure 12). Among them, the freshwater prawn is the indicator species for irrigation ditches, the Chinese softshell turtle for grassy irrigation ditches, the paradise fish for ecological ponds, and the Taiwan blue magpie (Level III-Other conservation-deserving species), the leopard cat (Level I- Endangered species), and the crested serpent eagle (Level II – Rare and valuable species) for the surrounding foothill ecosystem.

Besides organic and eco-friendly rice farming that follows standard of green conservation, community residents restore and manage three ecological sites as reproduction grounds for the freshwater prawn and Sanyi type paradise fish. They also maintain a 3,156-meter-long grassy ditch that provides a stable water source, shelter, habitat, and movement pathway for Chinese softshell turtles. Moreover, the eco-farming rice fields are habitats for amphibians, reptiles, frogs, rodents, and insects, as well as supply stable food sources to the Taiwan blue magpie, leopard cat, and crested serpent eagle. Lastly, local farmers also commit to keep the integrity of surrounding forests for the purpose of water resources and wildlife habitat conservation (e.g., the Taiwan blue magpie, leopard cat, and crested serpent eagle).

In order to increase incomes and enhance economic drivers, The small-holder farmers in the Liyu Community work together to develop a green production chain. This organic rice green production chain consists of six stages. For the primary industrial production, the rice variety grown is Taichung 194. This variety is characterized by good plant shape and is not prone to collapse, which facilitates organic cultivation and management. Seeds and seedlings are provided by the farmer’s association and plowed using machines by members of the local production and marketing group. If encountering any problems related to the cultivation process, MDARES and NCHU (the organic certification sector) will provide consultation services and technical assistance. In addition, the production and marketing group members will share experiences or exchange ideas among themselves.

To avoid cross contamination, the harvesting machine for organic rice must be separated from the conventional rice post-harvest processing system, becoming an independent one. The Miaoli Organic Food Production Cooperative assists Liyu’s small-holder farmers with harvesting, drying, and milling organic rice. The processed rice products are primarily produced in cooperation with Shanfeng Food Industry Co., Ltd. The rice is also used to produce Rice Stars, a rice-based snack targeted toward babies or children under 12 years old.

These small-holder farmers join forces with the Sanyi Township Farmers’ Association, THU, NCHU, and SWCB to hold agrotourism activities that enable tourists understand rice fields and rural community development better. These activities are intended to let consumers know where their rice comes from, understand how it is produced, build a connection to the product, and enhance mutual trust between producers and customers. This approach is in line with the Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) proposed by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM). The PGS refers to the establishment of a communication channel between local small-scale farmers and consumers through various means to strengthen the connection and trust between the two in the hope that consumers promote the purchase of small-scale agricultural products.

Speaking of the production, marketing and sales, smallholders often abandon organic farming and return to conventional farming due to their lack of technical know-how for the former and inadequate marketing channels for organic rice. The organic rice industry chain in the Liyu Community is a result of the integration of resources from public and private sectors; the cooperation of organizations and personnel with different abilities at the first, second, and third stages; and improvements to smallholders’ production techniques and marketing capabilities, which has allowed the Liyu Community to address its past issues.

Key messages

Farmers of Liyu community practices organic farming or eco-friendly farming (i.e. reduced use of agrochemicals) to protect farmland ecosystem from ongoing habitat loss and degradation, support biodiversity and enhance ecosystem health. On top of that, the organic (or eco-growing) rice can not only ensure responsible and sustainable production but also enhance human physical health than conventional farming.

Regarding the SEPLS management, farmers make use of excess water resources in rice paddy and then develop a transformative way to control rice blast disease, literally, turning a disadvantage to a useful mean. They also implement several practices that can benefit crop production and biodiversity conservation mutually, for examples, use of Azolla as a green manure in rice cultivation, no herbicide spray, and creation of ecological ponds as biological refuge during non-growing time (i.e., rice fields would be left dried).

Crop fields are used for the purpose of environmental education, recreation and community events, which strengthen consensus among residents, enhance physical and mental health, as well as improve human wellbeing of community. Moreover, with establishing a cross-sectoral platform, Liyu community promotes responsible production and consumption (e.g., Participatory Guarantee System) , develops green production chain, that can provide adequate economic drivers to pursue the SDGs.

Relationship to other IPSI activities

Funding

1. The main project of this case study is funded by Taichung Branch of the Soil Water Conservation Bureau, COA., ROC. (Chinese Taipei)

2. Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of China, Taiwan financially supports parts of this research under Contract 109-2621-M-002 -008 -MY3 and 109-2625-M-005 -002 -MY2.

3. The work related to policy communication, environmental education and outreach was also supported by the “Innovation and Development Center of Sustainable Agriculture” from the Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

References cited

- Lodge, DM 1993, ‘Biological invasions: lessons for ecology’, Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 8, No.4, pp. 133-137.

- Baker, GH 1998, ‘The golden apple snail, Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck) (Mollusca: Ampullariidae), a potential invader of fresh water habitats in Australia’. In Sixth Australasian Applied Entomological Research Conference, Vol. 2. University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, pp. 21-26.

- Postgate, J 1998, Nitrogen Fixation (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Cowie, RH 2002, ‘Apple snails (Ampullariidae) as agricultural pests: their biology, impacts and management’, In M. Barker (Ed.), Molluscs as Crop Pests, CAB-International, Wallingford, UK , pp. 145-192.

- Estebenet, AL, Martín, PR & Burela, S 2006, ‘Conchological variation in Pomacea canaliculata and other South American Ampullariidae (Caenogastropoda, Architaenioglossa)’, Biocell, 30, no. 3, pp. 329-335.

- Chen, TJ 2006, Colorful Butterfly: Taipei Butterfly Guide, Min Sheng Daily, Taipei, ROC. (Chinese Taipei).

- Rawlings, TA, Hayes, KA, Cowie, RH & Collins, TM 2007, ‘ The identity, distribution, and impacts of non-native apple snails in the Continental United States’, BMC Ecology and Evolution, 7 , Article 97.

- Seuffert, ME & Martín, PR 2009, ‘Influence of temperature, size and sex on aerial respiration of Pomacea canaliculata (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae) from Southern Pampas, Argentina’, Malacologia, 51, no. 1, pp. 191-200.

- UNU-IAS, 2010, Biodiversity and Livelihoods: the Satoyama Initiative Concept in Practice. Institute of Advanced Studies of the United Nations University & Ministry of Environment of Japan, Yokohama, Japan.

- Bélair C., Ichikawa K., Wong B.Y. L., & Mulongoy K.J. (Eds.) 2010, Sustainable use of biological diversity in socio-ecological production landscapes—Background to the ‘Satoyama Initiative for the benefit of biodiversity and human well-being’, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal. Technical Series no. 52, 184

- Miaoli County Government, 2016, The Ecological Green Book of the Liyu Community in Sanyi Township, Miaoli County Government, Miaoli County, ROC (Chinese Taipei).

- Taichung Branch, Soil and Water Conservation Bureau, , 2017, 2017 Rural Community Intelligent Disaster Prevention and Satoyama Initiative Practice in Hillside Area. Taichung Branch of SWCB, COA Taichung City, ROC (Chinese Taipei).

- Taichung Branch, Soil and Water Conservation Bureau, COA., 2018, 2018 Strategy Development and Implementation of the Sotoyama Initiative in Chung-Miao Rural Communities. Taichung Branch of SWCB, COA Taichung City, ROC (Chinese Taipei).

- Leimona, B, Chakraborty, S & Dunbar, W 2018, ‘Policy Brief–Mainstreaming incentive systems for integrated landscape management: Lessons from Asia’, Policy Brief 16 November.

- Liu, YS 2018, ‘Rice fields are stocked with “Alloza” to prevent weeds and are naturally high in nitrogen fertilizer’, News & Market, 19 October, 2018 < https://www.newsmarket.com.tw/blog/113606/>.

- UNU-IAS and IGES (eds.), 2018, Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review 4: Sustainable use of biodiversity in socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes and its contribution to effective area-based conservation, UNU-IAS, Tokyo, Japan.

- Haase, P, Tonkin, J, Stoll, S, Burkhard, B, Frenzel, M, Geijzendorffer, IR, Häuser, C, Klotz, C, Kühn, I, Mcdowell, W, Mirtl, M, Müller, F, Musche, M, Penner, J, Zacharias, S & Schmeller, D 2018, ‘The next generation of site-based long-term ecological monitoring: Linking essential biodiversity variables and ecosystem integrity’, Science of the Total Environment, doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.11.

- Legislated List of Protected Species in Taiwan (Wildlife Conservation Act) 2019 (Cwlth).

- Miaoli County Government Household Registration Service 2020, the Miaoli County Government Household Registration Office, Miaoli County, ROC (Chinese Taipei), viewed 29 December 2020, < https://miaoli.house.miaoli.gov.tw/>.

- Tainan District Agricultural Research and Extension Station, 2020, the Tainan District Agricultural Research and Extension Station,, Tainan City , ROC (Chinese Taipei), viewed 15 December 2020, <https://www.tndais.gov.tw/en/index.php>.

- Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute, 2020, the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute, COA., Taichung City, ROC (Chinese Taipei), viewed 15 December 2020, < https://www.tari.gov.tw/english/>.