Initiation of SEPLS Approach from World Peace Biodiversity Park (WPBP), Pokhara in Panchase Region of Nepal (SITR8-3)

17.03.2024

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

Back to Nature

DATE OF SUBMISSION

19/09/2023

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Nepal

AUTHOR(S)

Dambar Pun, Aashish Tiwari

Pabin Shrestha

Kapil Dhungana

Gunjan Gahatraj

Dem Bahadur Purja Pun

LINK

1 Background on the Panchase Forest Conservation Area

Nepal is blessed with rich biodiversity. According to Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation (MoFSC) (2014), Nepal is home to 6973 species of angiosperm and 26 species of gymnosperm. Koirala (1998) reported 306 plant species, including some medicinal plants from Panchase. Subedi (2002) reported 170 species of orchids around Pokhara Valley, of which 98 were from Panchase. The Panchase Protected Forest (PPF) hosts a total of 613 species under 393 genera and 111 families of flowering plants (Bhandari et al. 2018), and harbours unparalleled natural attractions and fantastic mountain landscapes (IUCN 2014; Neupane et al. 2021). In recognition of the rich biodiversity, forest resources, and cultural and spiritual values of the area, PPF was gazetted as a “Protected Forest”, under Article 23 of the Forest Act in February 2012 (Suwal et al. 2013; DoF. 2012). Panchase, which literally means “five seats”, is the meeting place of five hills, and is located in the Mid-Hills of Nepal (Baral et al. 2017). Subsequently, Protected Forests were renamed Forest Conservation Areas by the Forest Act of 2019.

Panchase region, a representative mid-mountain ecological zone of Nepal (Bhattarai et al. 2011), also functions as a river corridor between Chitwan National Park and Annapurna Conservation Area. Unlike other corridors, Panchase is a northsouth corridor with great significance for wild animals during extreme climate events. Community and national forests constitute the important forest ecosystem of Panchase. The forest ecosystem provides both provisioning and regulating services, such as soil erosion control, maintaining e-flow, and reducing siltation in Lake Phewa. This landscape supports rare, threatened, and endemic plant species, including six endemic and three threatened orchid species (Bajracharya et al. 2003; Subedi et al. 2007, 2011; Måren et al. 2014; Raskoti 2015; Bhandari et al. 2018). Four of these species—Eria pokharensis, Gastrochilus nepalensis, Odontochilus nandae, and Panisea panchaseensis—are local endemic (Bajracharya et al. 2003; Subedi et al. 2011; Raskoti 2015; Raskoti and Kurzweil 2015) and the other two—Begonia flagellaris H. Hara (Begioniaceae) and Oberonia nepalensis (Orchidaceae)—are region endemic and distributed in Central Nepal (Shakya and Chaudhary 1999; Rajbhandari and Adhikari 2009; Rajbhandari and Dhaugana 2010; Bhandari et al. 2018), including in and around the Panchase region. Beneficiaries of the different ecosystem services of the Panchase landscape range from those at the local level to the sub-national, national, and global levels (Bhandari et al. 2018).

1.1 Ecotourism in the Panchase Forest Conservation Area

Ecotourism as a component of the sustainable green economy is one of the fastest growing segments of the tourism industry due to its superiority compared to other types of tourism in terms of responsibility towards people, nature, and the environment (Poudel and Joshi 2020). Ecotourism has the potential to increase investment, jobs, exports, and technologies in the least developed and small island countries, whilst inflicting minimal adverse environmental impacts (Mazzarino et al. 2020). Since ecotourism is intrinsically linked with natural assets and cultural heritage, local and indigenous communities conserve and manage biodiversity and natural assets if they receive benefits. Practices that link local communities with the environment through ecotourism have played a significant role in mitigating climate change impacts and attaining development goals (K. C. and Thapa Parajuli 2014). Ecotourism supports environmental conservation and the sustainable development of affected communities (K. C. 2017).

The terrestrial ecosystem of the Panchase Forest Conservation Area (PFCA) consists of different land use types with forest covering 61% of the total area, followed by agriculture, grassland, and wetland covering 34%, 3%, and 1.3%, respectively (Adhikari et al. 2019). The upper region is managed primarily for the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems. Pristine and dense forest provides provisioning services (i.e. fuelwood, wild fruits, medicinal and aromatic plants, and water), regulating services (i.e. water purification), and cultural services (i.e. recreation, aesthetics, and spiritual values) (Adhikari et al. 2019). The forest in the lowland is mainly managed as a community forest and is regarded as the fringe area of the PFCA (Adhikari et al. 2019). Panchase region provides habitats for 589 species of flowering plants, 24 species of mammals, and 262 species of birds, maintaining life cycles and genetic diversity (Bhandari et al. 2018). Maintaining the landscape’s integrity and heritage has allowed it to provide recreation and tourism opportunities for the roughly 3600 tourists and 25,340 pilgrims that visit every year (Bhandari et al. 2018). Mass tourism has brought changes to the lifestyle of the local people, lessening their adherence and attraction towards their own heritage. Indeed, the decline in consideration for conservation and protection of natural resources exhibited in their overuse in the PFCA has resulted in degradation of the environment, loss of economic benefits due to damage to resources or the local community, and disruption of local culture and values (Gautam 2020). Promoting ecotourism greatly emphasises raising the awareness of both communities and visitors, and allowing for equitable benefit sharing of tourism business with local communities.

2 Description of Study Area

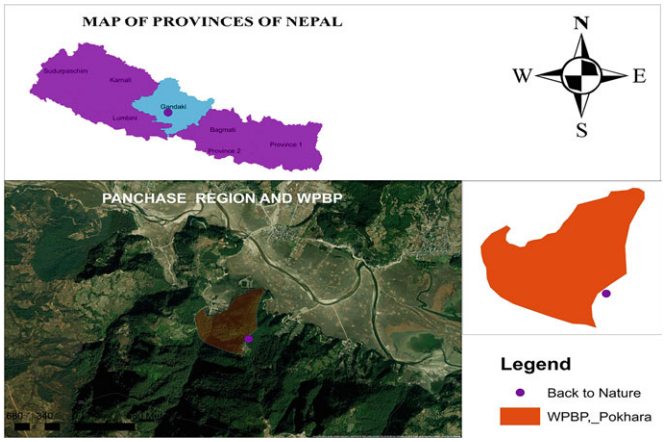

World Peace Biodiversity Park (WPBP) is a small fractional portion of the Panchase Forest Conservation Area that is located 20 kilometres away from Pokhara, the capital of Gandaki Province (Fig. 4.1). WPBP contains a wide range of plant and animal species in Schima-Castanopsis forest, including Schima wallichi; Castanopsis species; differing orchid species; 35 identified bird species, like red junglefowl, kalij pheasant, and common dove; common leopard; black bear; barking deer; porcupines; snakes; and different species of insects like butterflies and fireflies. The mosaic of land uses is characterised by agriculture, forestry, fisheries, animal husbandry, and tourism, which are the main economic activities of over 500 households of Gurung, Magar, Chettri, and Dalit ethnic communities from Nepal.

WPBP covers an area that is mostly part of the Jauchare Dadhakarkha Bhirim Community Forest, as well as the adjoining Bhedikharka and Jhapulokhe Kharka Community Forests. These community forests constitute the upstream area of Lake Phewa and are integral to the Lake Phewa basin due to the interacting livelihoods of both the upstream and downstream communities, and regulation of the e-flow of Lake Phewa. Although forests provide various goods and services for human wellbeing, the importance of ecosystem services arising from forests is not properly recognised in Nepal (Bhandari et al. 2018).

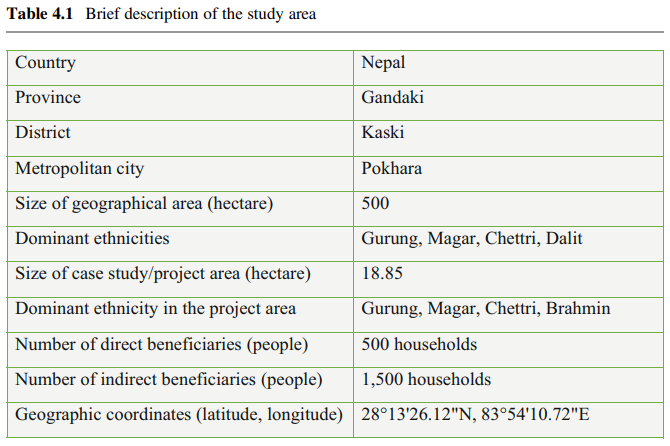

The WPBP area also falls under the Phewa Protected Watershed, designated by the Government of Nepal on 9 February 2022. Phewa watershed is a prime example of participatory watershed management in Nepal (Table 4.1).

2.1 Conservation Value and Challenges

Forests under PFCA are managed and operated by community forest user groups (CFUGs), which are legally entitled autonomous institutions, through operational plans that are technically supported by government and approved for implementation. These CFUGs carry out various activities including planting seedlings, controlling wildlife hunting, fighting forest fires, regulating grazing, monitoring forest encroachment, protecting the forests from natural hazards, and harvesting and regulation of the forest crop. However, the selection of high-value or preferred species, removal of old trees or unwanted species, heavy leaf litter collection, and illegal logging have detrimental impacts on the biological diversity and ecosystem function of community-managed forests (Shrestha et al. 2010).

The older generation has experienced and coevolved with the surrounding biodiversity, which has shaped attitudes, values, and beliefs related to biology, ecology, and use of the biodiversity (Popova 2014) in the WPBP area. However, younger generations are gearing towards off-farm income options, including tourism and foreign employment. This kind of generational economic shift has generated various issues, including the degradation of local and traditional knowledge on biological and cultural diversity, which has been a limiting factor behind the success of biodiversity conservation and ecotourism (Popova 2014). The PFCA is no exception in this regard. Outmigration amongst youth is substantial, resulting in labour shortages for forestry activities, farming, and livestock husbandry.

Issues such as dying water springs and water sources, invasive alien species, farmland abandonment, decrease in forest product availability, impacts of forest fires, and insect and disease outbreaks, are resulting in changes to the ecosystem services of Panchase region due to both natural and anthropogenic influences (Adhikari et al. 2019). Disturbance of wildlife due to mass tourism, haphazard village road construction, and encroachment on forests for constructing hotels and lodges, are other conservation challenges. Concerted efforts on the part of government authorities, local institutions, and local communities are of the utmost importance to address these issues and challenges to protect and enhance the conservation value of the PFCA, including WPBP.

3 Technical Approaches and Methods

The project adopted a participatory and iterative approach—employing a continuous cycle of action and reflection to ensure improved action. The participatory approach entailed bottom-up initiatives where local and indigenous communities were intensely involved in all activities. Collaborative work between indigenous people and external agencies is a key task towards improving the local and indigenous economy and relations with external actors, whilst also serving as a means to care for the environment across geopolitical boundaries (Popova 2014). The main vision behind WPBP, as stated in the management plan, lies in the prospect of promoting ecotourism based on biodiversity and cultural aspects whilst applying the principles of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which is also aligned with the socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS) concept. SEPLS are the result of the interactions of nature and society in a given geographical and temporal context whose sustainability through time has depended on the careful management of ecosystem services and the multifunctional use of land within the carrying capacity and resilience of the environment. As a result, they constitute examples of areas with high capacity for biodiversity conservation, socioeconomic development, and preservation of cultural assets such as traditional knowledge and local traditions (Bélair et al. 2010). In light of the principles prominently embedded in the SEPLS concept, ecotourism has more benefits compared to adverse impacts on the environment, society, and culture.

3.1 Roles of Different Stakeholders

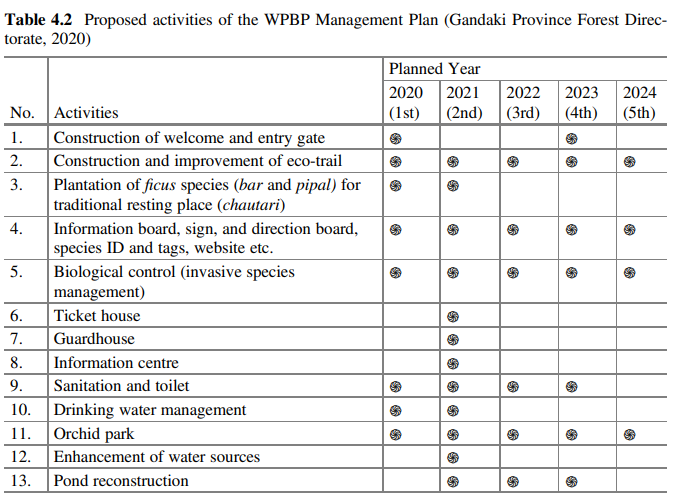

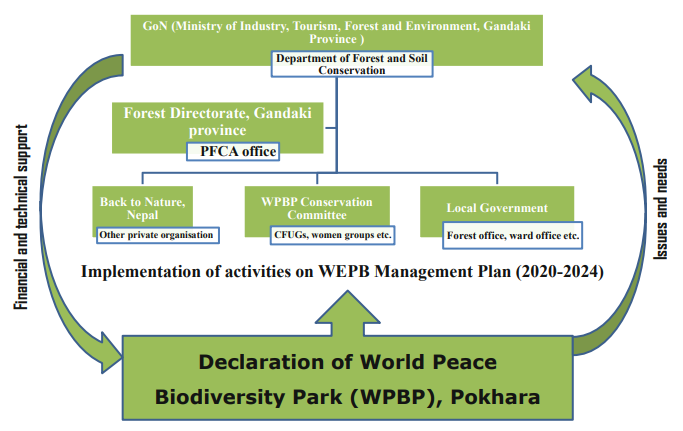

Back to Nature, a privately owned ecolodge established in 2011 with the aim of initiating conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity based on ecotourism in the Panchase landscape utilising local resources, values, customs, and folklore that foster the socio-economic well-being and resilience of the ecosystem. As a local entrepreneur, Back to Nature (Fig. 4.1) has made collective efforts to create an enabling environment for community participation, whilst providing support and lobbying on financial and technical aspects and coordinating during implementation of activities (Table 4.2). These were crucial for the transformation and reformation of the community forest into the politically recognised WPBP. Back to Nature provides and promotes ecotourism activities in the Panchase landscape, like trekking, jungle walks, bird watching, and homestays. It also supplements nature-based tourism activities like paragliding, rafting, and so on.

Community-based organisations like CFUGs, women’s group, farmer’s group, indigenous ethnic groups, street development committee, school teachers, and local communities, each have a niche in the ecotourism development and conservation priority activities of WPBP (e.g. school, youth club, and women’s group were trained in education on biodiversity and ecotourism). Government organisations like the Provincial Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment; and line agencies like the Gandaki Province Forest Directorate, Panchase Protected Forest Office, the ward office, and others, have provided financial and technical support for formulation, implementation, and evaluation of activities, and provided government representation on the WPBP conservation committee.

3.2 Activities and Measures

The Provincial Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment, Gandaki Province provided technical support for the formulation and development of the WPBP Management Plan (2020–2024). This plan, primarily premised on biodiversity conservation and ecotourism development, charted out a set of activities for the 2020–2024 period. Activities are implemented by the conservation committee formulated under the WPBP user group and former community forest user groups, with representation from Back to Nature, the women’s group, and other communitybased organisations (Table 4.2). These activities are implemented by the WPBP conservation committee, which was transformed with an enhanced governance structure (Fig. 4.2).

4 Results

The results summarised below were obtained from implementation of the first year of activities in the WPBP management plan (Table 4.2). The WPBP conservation committee with coordination from Back to Nature aims to carry out ecotourism development and biodiversity conservation on the adjacent Panchase landscape through implementation of activities in the management plan based on a SEPLS approach mainstreaming with the principles of the CBD and ecotourism.

Visitors are mesmerised, educated, and healed when finding themselves near the lush green forest, waterfalls, and beautiful landscape, and exposed to the simple rural life and friendly people. Tourism activities, such as forest walks, trekking amidst lush green forests, dew walks, scenic mountain views, wild animal sightings, orchid treks, and firefly watching, greatly enhance the tourism experience of visitors. According to the local people, conservation of nature and biodiversity is important since they are dependent on nature for ecotourism. Households having an ecotourism business were found to have greater awareness about the significance of biodiversity conservation and the role played by ecosystem services, as well as awareness of meetings and capacity building trainings held during formation of WPBP (Fig. 4.3). With the active leadership of Back to Nature alongside the generous support of the Government of Nepal and local communities, the desired results of conservation education and ecotourism development have been achieved to a great extent.

WPBP has been managed by a conservation committee advisory under the Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment, Gandaki Province. The conservation committee is mandated to take a leadership role in operating WPBP, as well as fundraising and financial management with potential national and international donors. The committee aims to publish information on the WPBP declaration and activities in national and local newspapers and online on social media platforms.

Impacts from society on the environment are to be minimised with the initiation of the SEPLS approach in the Panchase landscape and the development of ecotourism.

The ecotourism business operated in communities has put forth its best effort to provide authentic native and local cuisine, which offers unique tastes and promotes traditional knowledge and systems. This effort also prevents economic leakage, as most spending is retained in the local economy. As per the framework of the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC), sustainable ecotourism should benefit local and indigenous communities in an equitable manner. Equally important is educating visitors on local culture, heritage sites, and the significance of cultural assets in the promotion of ecotourism. Ecotourism has further motivated local and indigenous people to preserve and renovate cultural heritage sites such as monasteries, main walls, stone scriptures, and fresco paintings. WPBP was equipped with a welcome gate leading to the entrance path. In addition, a trekking trail of approximately 300 m (2 m in width) was constructed to give visitors a quality trekking experience amidst the lush green forest and along a stream (Fig. 4.4). Due to a lack of effective coordination and support, the plan for a ticket house had to be moved to an upcoming year. The objective of these building activities was to add value to the ecotourism experiences of visitors and help generate benefits for the local and indigenous communities. Without benefits, local and indigenous communities will not take ownership of conservation and protection of these tourism assets.

Three rectangular chautari (traditional resting platforms) and one rectangular pond/wetland were constructed in the vicinity (Fig. 4.5). Customs, folklore, and traditional belief systems provided the primary factors for the design of these structures, which mirror traditional religious beliefs and local values. Chautari (traditional resting places) provide brief shelter for villagers, trekkers, and livestock herders on hot summer days. Oftentimes, local people gather in chautari to discuss the community agenda, but this trend has been weakening. Ponds are conserved and renovated to hold rainwater to the maximum extent. Natural ponds are used for irrigation, livestock drinking water, and recharging downstream villages and the sub-watershed. They have impervious clay or synthetic liners and engineered structures to control flow direction, liquid detention time, and water level (Kadlec and Zmarthie 2010). These structures can be vital to combat sedimentation, soil erosion, and the impacts of climate change on the Lake Phewa basin.

An information board was built and placed near the welcome gate (Fig. 4.6) to inform visitors of the objectives of WPBP and associated activities (Table 4.2). This information has improved the quality of the trekking experience for visitors. Three garbage buckets and an accessible toilet were also constructed along the eco-trail. These help to manage waste properly and keep the environment pollution free.

5 Discussion

The activities mentioned in the management plan include regulation of overharvesting and encroachment concurrent with the community forests of Nepal. The management plan was likewise oriented towards protecting water sources in the Phewa watershed for siltation control, with focus on services like drinking water and irrigation. Construction of chautari using ficus species, a traditional plant characterised by its long life, high branches, and adaptive features, was important from both biodiversity and sociocultural perspectives. In the context of participation, communities have shown a high level of active participation compared to the previous community forestry regime. This is due to motivation from government commitment, indirect incentive generation, leadership development, and sustainable resource management from conservation and ecotourism-related activities in the management plan. The participatory approach with provisions for participation from women’s groups, youth clubs, and schools, have contributed to traditional knowledge regeneration and conservation. The increasing trend of visitors to WPBP has also motivated youth, communities, and the private sector to engage in entrepreneurship (ecolodge), like Back to Nature.

Incentives provided by visitors and donor agencies will be utilised to further explore, initiate, and develop nature-based tourism activities like orchid and bird tourism, jungle walks, and butterfly watching in WPBP and the adjoining Panchase landscape. The vision behind the declaration of WPBP as a tiny portion of the whole Panchase landscape was to initiate a conservation and restoration programme through an endangered orchid park and protection programme for insects (especially fireflies and butterflies). Implementation of all activities in the management plan is to extend through 2024. The environment of participation, coordination, and commitment will provide the essential physical, social, and financial resources to initiate the orchid park programme based on protection, collection, and farming of orchid species in the park area. These synergies and trade-offs for in situ conservation and sustainable use through ecotourism can subtly be referred to as a “Living Laboratory on Ecotourism”.

Back to Nature, along with coordination from the conservation committee and community forests, is planning to initiate an eco-trail connecting the religious Shiva temple and Biodiversity Park to further enhance trekking experiences. Initiation of such public–private partnerships is innovative in itself, but challenges lie ahead, particularly on three fronts: (1) institutional capacity building of the conservation committee; (2) scaling up best practices out of all activities; and (3) ensuring financial sustainability through effective networking with potential national and international donor communities. Moreover, some pertinent issues, e.g. outmigration, human–wildlife conflict, forest fires, expansion of invasive alien plant species, and village road-induced landslides, must be addressed via concerted efforts and partnerships with government, NGOs, and donor communities. Finally, carrying capacity must be considered and prompt decisions made to address the issue of ecosystem restoration. Political instability and government organisational transformation1 in the country have been a serious issue affecting the sustainability of WPBP, which relies on the government for technical and financial support. Another issue is operationalising of the conservation committee based on a sustainable flow of financial resources, which has been a delimiting factor for its sustainability and coordination effort in decision-making.

1 Due to internal political conflicts in Nepal, government institutions like the Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment, Gandaki Province, were dissolved and the provincial ministry with power to regulate the PFCA and WPBP, Pokhara was changed to the Ministry of Forest, Environment and Soil Conservation, Gandaki Province.

6 Conclusions

The declaration of WPBP in the Panchase landscape and implementation of various activities intrinsically linked to biodiversity and ecosystems have had positive impacts on restoring ecosystems, primarily with regards to: (1) forest and (2) water. Perhaps the best explanation of the correlation between ecotourism and ecosystem restoration can be found in the fact ecotourism spurred the local and indigenous people to confirm their stake in ecosystem restoration and made them aware that the very future of both ecotourism and the people themselves is reliant on a resilient ecosystem. WPBP in the Panchase landscape has created opportunities beyond the traditional resource management of community forestry with indirect use of cultural services and integration of local and scientific knowledge. It has provided incentives for conservation and restoration programmes in the degraded forest and agricultural ecosystem based on a SEPLS approach. However, these ecosystems are increasingly impacted by both climatic factors and anthropogenic threats. The financial and technical support of government agencies in the declaration process of WPBP and associated activities demonstrates that existing policy and legislative frameworks support the WPBP initiatives. The local and indigenous people of the Panchase landscape have a distinct and age-old relationship with the nature and biodiversity of the area that is essential for their survival and livelihoods. The activities of the management plan of WPBP have yielded positive results in terms of sustainable use of biological resources by adopting long-term sustainability, enhanced governance, and effective conservation of the SEPLS. Finally, further enhancement and perpetual succession of the WPBP and SEPLS concepts will require continued and effective coordination by Back to Nature along with the key stakeholders, including government authorities, local institutions, and donor communities.

References

Adhikari S, Baral H, Sudhir Chitale V, Nitschke CR (2019) Perceived changes in ecosystem services in the Panchase Mountain ecological region, Nepal. Resources 8(1):4

Bajracharya DM, Subedi A, Shrestha KK (2003) Eria pokharensis sp. nov. (Orchidaceae); a new species from Nepal Himalaya. J Orchid Soc Ind 17:1–4

Baral S, Adhikari A, Khanal R, Malla Y, Kunwar R, Basnyat B, Gauli K, Acharya RP (2017) Invasion of alien plant species and their impact on different ecosystems of Panchase area, Nepal. Banko Janakari 27(1):31–42

Bélair C, Ichikawa K, Wong BYL, Mulongoy KJ (2010). Sustainable use of biological diversity in socio-ecological production landscapes. Background to the ‘Satoyama initiative for the benefit of biodiversity and human well-being

Bhandari AR, Khadka UR, Kanel KR (2018) Ecosystem services in the mid-hill forest of western Nepal: a case of Panchase protected forest. J Ins Sci Technol 23(1):10–17

Bhattarai KR, Måren IE, Chaudhary RP (2011) Medicinal plant knowledge of the Panchase region in the middle hills of the Nepalese Himalayas. Banko Janakari 21(2):31–39

DoF. (2012) Panchase protected forest management plan. Department of Forest (DoF). Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation (MoFSC), Government of Nepal, Kathmandu

Gautam V (2020) Examining environmental friendly behaviors of tourists towards sustainable development. J Environ Manag 276:111292

IUCN (2014) Strengthening homestay business for diversifying livelihoods: building local people‘s resilience against climate change in the Panchase area. International Union for Conservation of Nature, p 4

K. C. A (2017) Ecotourism in Nepal. The Gaze J Tourism Hospitality 8:1–19

K. C. A, Thapa Parajuli RB (2014) Tourism and its impact on livelihood in Manaslu conservation area, Nepal. Environ Develop Sustain 16(5):1053–1063

Kadlec RH, Zmarthie LA (2010) Wetland treatment of leachate from a closed landfill. Ecol Eng 36(7):946–957

Koirala RA (1998) Botanical diversity within the project area of Machhapuchhre development organization, Bhadaure/Tamage VDC, Kaski district. A baseline survey for Machhapuchhre development organization (MDO). Bhadaure/Tamage, Kaski District, Nepal

Måren IE, Bhattarai KR, Chaudhary RP (2014) Forest ecosystem services and biodiversity in contrasting Himalayan forest management systems. Environ Conserv 41(1):73–83

Mazzarino JM, Turatti L, Petter ST (2020) Environmental governance: media approach on the United Nations programme for the environment. Environ Develop 33:100502

MoFSC. (2014) Nepal biodiversity strategy and action plan 2014–2020. Government of Nepal, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal

Neupane R, KC A, Aryal M, Rijal K (2021) Status of ecotourism in Nepal: a case of BhadaureTamagi village of Panchase area. Environ Dev Sustain 23(11):15897–15920

Popova U (2014) Conservation, traditional knowledge, and indigenous peoples. Am Behav Sci 58(1):197–214

Poudel B, Joshi R (2020) Ecotourism in Annapurna conservation area: potential, opportunities and challenges. Grassroots J Nat Resour 3(4):49–73

Rajbhandari KR, Dhaugana SK (2010) Endemic flowering plants of Nepal, part 2. DPR Bull. Sp. Publication, Thapathali, Kathmandu

Rajbhandari KR, Adhikari MK (2009) Endemic flowering plants of Nepal, part 1. DPR Bull. Sp. Publication, Thapathali, Kathmandu

Raskoti BB (2015) A new species of Gastrochilus and new records for the orchids of Nepal. Phytotaxa 233(2):179–184

Raskoti BB, Kurzweil H (2015) Odontochilus nandae (Orchidaceae; Cranichideae; Goodyerinae), a new species from Nepal. Phytotaxa 233(3):293–297

Shakya LR, Chaudhary RP (1999) Taxonomy of Oberonia rufilabris (Orchidaceae) and allied new species from the Himalaya. Harv Pap Bot:357–363

Shrestha UB, Shrestha BB, Shrestha S (2010) Biodiversity conservation in community forests of Nepal: rhetoric and reality. Int J Biodiv Conserv 2(5):98–104

Subedi A, Chaudhary RP, Vermeulen JJ, Gravendeel B (2011) Panisea panchaseensis sp. Nov. (Orchidaceae) from Central Nepal. Nord J of Bot 29:361–365

Subedi A (2002) Orchids around Pokhara valley of Nepal. In: LI-BIRD occasional paper no.: 1. Local initiatives for biodiversity. Research and Development (LI-BIRD), Pokhara

Subedi A, Subedi N, Chaudhary RP (2007) Panchase Forest: an extraordinary place for wild orchids in Nepal. Pleione 1:23–31

Suwal RN, Bhuju UR, Tiwari KR, Pokhrel RK (2013) Preliminary identification of essential and desirable ecosystem services in the Panchase area of Nepal. A report environmental camps for conservation awareness (ECCA)/United Nations environment program (UNEP)

Note

The opinions expressed in this chapter are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNU-IAS, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent.

Open Access This chapter is licenced under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ igo/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to UNU-IAS, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. If you remix, transform, or build upon this book or a part thereof, you must distribute your contributions under the same licence as the original. The use of the UNU-IAS name and logo, shall be subject to a separate written licence agreement between UNU-IAS and the user and is not authorised as part of this CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO licence. Note that the link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the licence.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from

the copyright holder.