Human-nature connection and well-being of the H’re indigenous community in production landscapes of Kon Tum Province, Central Highlands of Vietnam

19.02.2018

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Social Policy Ecology Research Institute (SPERI)

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

19/02/2018

-

REGION :

-

South-eastern Asia

-

COUNTRY :

-

Viet Nam (Kon Tum Province)

-

SUMMARY :

-

This paper is designed to contribute to enhancing knowledge on the linkage between humans and nature in a socio-ecological production landscape and seascape (SEPLS) through providing analyses of the livelihood activities of the H’re indigenous community in Kon Tum province, Central Highlands of Vietnam. We have documented the ways of life in the villages of ethnic H’re communities that exhibit all the characteristics of livelihoods linked with a SEPLS. Their spiritual ecosystem includes how they perceive and interact with their land and mountains, forests and water, clean air and natural landscape. Cultural rituals and ceremonies involve organization within the community for diverse rituals throughout the year to pay respect and gratitude to many Nature Spirits. Community cohesion relies strongly on their customary laws, but there are certain changes due to context. Villages have already come into contact with external interventions; however, the communities continue to exhibit leadership and find alternative ways to defend their livelihood sovereignty and maintain their well-being and the sustainability of the SEPLS.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Livelihoods; H’re community; Spiritual ecosystem; Challenges; Well-being; SEPLS sustainability

-

AUTHOR:

-

Kien Dang and Lanh Tran (SPERI/CENDI); Chon A, Chat Dinh and Nga Y (Po E Communal People’s Committee)

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Context and challenges

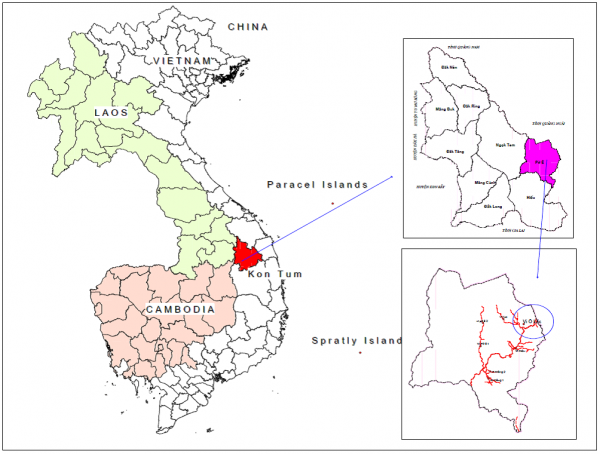

This paper is designed to contribute to enhancing knowledge on the linkage between humans and nature of the H’re people in an example of a SEPLS (socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes), through describing the livelihood activities of this indigenous community in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. The community is located in the Po E commune of Kon Plong district in Kon Tum province, as illustrated in Figure 1. It is one of the most remote communes in the area. The commune has seven villages with a total land area of about 11,189.72 hectares (Po E Communal People’s Committee 2013).

Figure 1. Map on the lower right shows the location of the site in Po E commune, Kon Plong district, Kon Tum province (Source: LISO 2016)

The H’re community and their socio-ecological village landscape system

The Po E commune is home to 100 percent H’re ethnic indigenous people. The living spaces of the H’re villagers are surrounded by unique natural landscapes often composed of mountains and hills, river valleys, rice farming areas, gardening spaces and residential housing (CENDI 2015). The people are hard-working and often working conditions require them to be under the sun, up in the hills and in the forests.

Figure 2. A H’re family with two children in one village and a H’re women’s group in another village (Photo: Dang)

A typical H’re person has a small body form, with slightly dark-coloured skin, as shown in Figure 2. The people are kind towards each other both in the same community and across communities. The H’re speak their own language and show great pride in it. Generally, they enjoy their natural landscape and feel happy expressing their culture and identities that are closely linked with their landscape (CENDI 2015). For special events, they wear traditional H’re clothes. The women are skilful in cultivation, forest use, and other resource management practices. The women’s groups tend to stay together, going to the field or helping each other out at any events.

H’re historical settlement and production activities

Historically, the H’re community has settled in the mountainous areas of Quang Ngai province, with a minor group settled in Binh Dinh province (Hoang 2013). These areas were explored and settled by their ancestors. The origins of the H’re are said to be attached to a mountain named Mum and a mountain named Rin from each specific locality (Hoang 2013; villagers’ stories 2014-2016).

- Traditional cropping and cultivation

As the H’re settled in areas between the high mountains and the valleys, often on flat agricultural fields with fertile soil along the river streams, they learned to use their ecological and topographical knowledge to form small rice terraces for farming (Hoang 2013). The rice cultivation of the H’re can be grouped into two types: dry rice fields in upper zones and wet rice fields in lower areas. The H’re are known to only farm one rice crop per year; however, occasionally there are places where people do farm two crops (villagers’ stories 2014-2016). Villagers tend to prefer summer cultivation as this gives them higher yields (Hoang 2013). This once-a-year rice farming is well known due to the high quality of local rice varieties. According to an elder, “our H’re people eat our local rice and can feel full; not like the white rice” (villagers’ stories 2016). This knowledge and experience has gone through years of selection, and it is useful to learn that the H’re have still saved their best local varieties today.

- Raising livestock

The H’re raise their livestock in herds, including buffaloes, cows, chickens and ducks, and they also hunt wild animals (villagers’ stories 2014-2016). Large animals such as buffaloes are placed separately from other animals like pigs and chickens, which are often raised free-range around the house. Buffaloes are used as an alternative to manpower, for instance to help carry things to the rice fields in the upper hills. During cultural events, buffaloes are sacrificed as offerings to the Spirits (Hoang 2013; villagers’ stories 2015). In special cases, they are also used as property to be exchanged for goods and services that villagers do not have internally. The H’re raise a lot of pigs and chickens for both meat and spiritual offerings. In the day time, they free them into the wild, and in the late afternoon, they go into the forests to call their herds home (villagers’ stories 2014-2016).

The works of SPERI and the LISO Alliance

The Social Policy Ecology Research Institute (SPERI) and the Livelihood Sovereignty Alliance (LISO Alliance) are amongst the few NGOs currently working on site. The main objective of these NGOs is to work with local villagers and concerned stakeholders to contribute to the livelihood sovereignty of the villages through securing community land titles whilst also defending recognition of customary law-based resource governance to defend against numerous emerging challenges (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2018).

Since 2014, activities at the site have successfully secured a total of 674.7 hectares of the community sacred forestlands, which have been legitimately put in the names of the four H’re villages. Securing of these sacred forestlands has contributed to maintaining the spiritual ecosystem and also the beliefs and indigenous worldviews that the H’re have long maintained, including interactions with the Mother Mountain, the Gifted Stream, the land and water and also the Gem Rice Field (CENDI 2015) (see section 3.2.3 below).

Through NGO activities, we also learned that despite villages having maintained the many aspects of their lives that are linked harmoniously and strongly to the natural landscapes, emerging challenges also exist. Conversion of forestland to cassava crops combined with promotion of herbicide use is one of the most critical. Many discussions have been raised by villagers and the LISO Alliance in order to search for lessons learned and solutions. Discussions have also been raised on the types of livelihoods needed to balance production, well-being and also SEPLS sustainability.

Methods

Information gathering and description of livelihoods for this thematic volume has built upon and been gathered with the obtained consensus of SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance and from the ongoing work of these organizations.

Field work based on direct observation

Our activities have involved a great amount of field work conducted from 2014 to present. Direct observations took place at all times in the field, around the rice paddies and other cropping areas, over the entire landscape, at each household visited and also during community meetings. We witnessed the livelihood aspects of the H’re by taking part in their daily activities to gain an understanding of their lives; including how and why they do things in their own ways, using customs and local knowledge (SPERI 2016).

Community discussions and in-depth hearings with villagers

Based on field work, discussions and notes were compiled. Direct and in-depth interviews were also conducted with most members of the villages, including women’s groups, elders’ groups, youth groups and farmers’ groups. For example, the most recent trip aimed to study how the H’re community harvests its rice crop and how it organizes the traditional ceremony to thank the Rice Spirits. Interviews occurred with all groups at the rice fields (e.g. area for harvesting, area for drying rice, place for storing rice). After intense listening, oral consultation was also undertaken with participants on local knowledge, such as with the women on local rice varieties for documentation and acknowledgement (SPERI 2016). Elders were mainly men and were consulted on knowledge of sacred or spiritual attachments. Youths were consulted on future plans for the village and for themselves.

Participatory mapping and documentation of indigenous knowledge

Initially, community meetings were held with villagers to discuss the identification of local terms for places of significance in their village lands. Both locations and names were documented and their meanings carefully recorded. The subsequent field work by groups of villagers also included a cultural officer from the district Department of Culture, a legal officer from the district Department of Justice, a Forestry officer and a Natural Resources officer. These officers also attended earlier meetings when possible. The field work was completed over three or four visits (or sometimes more) to ensure that the documentation was thorough. The inclusion of all participants ensured engagement, agreement and ownership of the mapping by everyone. The entirety of information gathered via field work was processed and mapped onto a formal Natural Resources map (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

Documentation came in various forms: written notes, photos, video and other materials recording the information obtained from the villagers with their oral permission. Final production of documentation acknowledged contributions from all. For certain activities, selected photos were printed and returned to communities. Villagers and local stakeholders were informed of video productions and release (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

Limitations of this paper

The results presented herein describe the livelihoods of the H’re and largely come from field observations and experiential learning from the villagers. Certain literature is integrated but to a large extent, primary information is provided. Our interpretation is dependent on what members saw and witnessed concerning how villagers practice their ways of life as well as information provided by the people. Our writing and description of results also respects another reality, that is that our usual history in Vietnam has often focused upon major events and milestone activities, and often pays little attention to the details of the smaller marginal groups such as the H’re ethnic group. We thought it necessary to make the effort to directly document knowledge and practices from villagers themselves so that their stories and ways of life can be acknowledged.

Peer review

This paper received comments and inputs from peers during a case study workshop held in Japan as well as other independent inputs. There was a list of 29 comments (or viewpoints) for exchange and contribution into the current draft version used for its improvement. A process was undertaken by the corresponding author to include and respond to those comments and inputs.

Results

The H’re people’s current practices

- Cropping and cultivation

Given that the soil type in the Central Highlands region is of high quality, ‘dark red-brown basalt soil’, there should be no need for additional fertilisers (villagers’ stories 2014). The H’re people in all villages continue practicing natural farming and production, e.g. putting seeds into the soil and just letting them grow by themselves (villagers’ stories 2014-2017). About 80 to 90 percent of families practice natural farming as illustrated in Figure 3. Livestock continue to be raised freely and food sources are natural. Local cropping and breeding varieties are continuously saved and replanted.

Figure 3. H’re cultivate maize by natural farming methods. Pigs and chicken are free-range (Photo: Dang)

The H’re community uses local varieties for subsistence and home consumption in both livestock and farming. Local cropping and breeding varieties are strongly connected to ritual ceremonies and the cultural lives of the people (CENDI 2015). New varieties, such as cash-crop cassava, corn and hybrid acacia, are not used by the H’re for any cultural or spiritual reasons. The villagers have also adopted different systems of labour exchange for local varieties versus new varieties. For traditional crops such as rice, the H’re people exchange or give help without any cash and with no concern for winning or losing amongst the families (CENDI 2015). For cash crops such as cassava and hybrid acacia, the villagers join in exchanges but members are paid either by cash or by labour.

Figure 4. H’re people using a machine to separate rice seeds from the rice plants (Photo: Dang)

Figure 5. The community helping a specific family during rice harvesting. The red circle highlights the cái hái—a tiny traditional knife that is placed within the palm to cut each of the rice plants by hand and then wrap them in bunches (Photo: Dang)

Production and harvests have remained largely traditional, but the recent presence of some mechanical intervention has been witnessed. In one village, out of all families, there were just one or two families that recently could afford to buy a machine that helps during the rice harvest. Groups of families borrow or hire this machine, and then when finished rotate the machine to another group of families for use. The machine helps to separate the rice seeds from the rice plants, as shown in Figure 4. In other villages, an arrangement of community rotational help for families during rice harvesting still in large part remains, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Little is yet known about whether the introduction of a rice harvesting machine into the community will have any effect upon social relationships, i.e. become a source of tension. Nevertheless, to date, the H’re have continued their usual social workforce arrangement, exhibited by labour exchanges and help-groups during rice harvests (CENDI 2015). Harvesting takes place yearly during the month of October. For all the steps involved in rice harvesting, the H’re work for one another without any cash payment requirements. On average, each family needs 20 people to come and help. Men are often in charge of the harvesting (in some cases now able to use a machine), women gather rice bunches from the rice field bringing them to the banks, and young people help to carry the rice bunches by hand from the banks to the machine. Youths also engage in rice separation from the plants whilst the women continue gathering rice into the rice bags and young people further help by carrying these rice bags to their homes. For all other community works such as house-building, building rice storehouses, and firewood harvesting, the H’re people help one another equally regardless of clan, age, status of the household, or social position, and no cash is involved (CENDI 2015).

Figure 6. H’re family starting their first rice cultivation (Photo: Dang)

Two photos (Figure 6 above) tell the story of a couple who walked for half an hour from home to this location for the best clean water. They settled on these two plots and started their first rice seeding. The husband prepared and cleared the two plots for flattening, mixed soft soil and water, firmed all the banks and edges, and followed up with the protective measures of laying wild pineapples leaves (meant to scare off bad luck from these new seeding plots). The wife silently greeted the Spirits, including all nature surrounding spirits, and spread the basket full of good rice seeds. They prayed for a good year with a good crop, good weather and a good harvest. These two plots are just used for the younger shoots to come up, after which the shoots can be transplanted in bigger plots. Even in their lives today, cultural and spiritual attachments during the production activities of the H’re appear fundamental (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

During other field work, we followed another group of women. In the morning, they called out to each other to go into the forest together. At a certain point in the wild, they divided into different groups searching in various directions. They searched for and collected leaves, roots and small tree branches of special types for their special ritual ceremony. Some women looked for roots whilst the younger ones climbed up trees to collect the youngest shoots in the uppermost parts (Figure 7, red circle).

Figure 7. H’re women searching for and collecting leaves and roots for the final bunch to present to Nature Spirits. The red circles highlight the villagers climbing trees (Photo: Dang)

The activity took them a whole day, searching for bunches of leaves to bring home to present to the Spirits. While practicing these activities, the women silently greeted the Nature Spirits, acknowledging them for everything they do.

- Houses for rice and houses for buffaloes

Another interesting finding concerns the H’re rice storehouses. Rice storehouses are built and made carefully of good structure, often located out near the rice fields, and separated from the residential areas. Rice and their bags are brought into the storehouses. The storehouses are framed with traditional bricks for roofing material, surrounded by wooden walls, often made with good timber. Each rice storehouse stands firmly upon sometimes four, sometimes six wooden poles, depending on each family. The H’re practice many ritual steps in building and using the rice storehouses (CENDI 2015). An example is painting each pole with certain pungent oils from some special trees in the forest to deter rats and animals from climbing up to the storehouse. The entire design was created by the H’re (Figure 8). All bags of rice must be included in rituals before entering storehouses.

Figure 8. An area of storehouses for the rice of the villagers (Photo: Le)

Another interesting finding concerns houses for buffaloes. As shown in Figure 9, the H’re spend a lot of time and resources on making safe and warm houses for animals. They are located further from home. The H’re have carefully made the roofing from a metal-based material to avoid damage by strong winds during the winter time. Pieces of wood are placed standing side-by-side to form the four walls. There is a little door big enough for the biggest buffalo to go through. None of the houses for buffaloes have locks; the H’re do not have a concept of locking doors (CENDI 2015). At the beginning of the year, there is a ceremony to greet the house for buffaloes as well, often happening in February. There are some hanging plants and a wooden bowl also hung in front of the entrance. These symbols signify the family’s asking the Spirits for good health for the buffaloes and wish to avoid bad luck for the herds of the family (CENDI 2015). Rice and buffaloes are not only important livelihood sources but also the cultural assets of the H’re.

Figure 9. H’re houses for buffaloes. The red circle indicates some hanging plants and a wooden bowl intended to ward off bad luck (Photo: Le)

- Forest use and management and customary norms

Two important sources of livelihood also derived in this SEPLS landscape are the forests and rivers and streams. In the forests, the H’re people collect forest vegetables, wild fruits, natural honey, birds, or wild animals, wood, rattan and bamboo, forest mushrooms, and much more. Rivers and streams are important sources of crabs, fish, snails, shrimps and other small freshwater fish, as shown in Figure 10. Collecting from nature in these ways has contributed to the daily lives of the people. The H’re always teaching and train their community members to protect these important sources of livelihood and not to pollute them, that they may continue to enjoy the natural foods they have to offer (CENDI 2015).

Figure 10. Crabs, fish, snails, shrimps and other small freshwater fish found in the stream (Photo: Le)

Each village has an area for common use and another area for family use. Individual family land area is the land used by a family, having long cultivated rice fields on it, including uphill cultivation areas, residences and houses for animals. The common land area is known as community forestland that has had little external intervention. It is commonly used and accessed by all villagers. Likewise, everyone follows village rules and customs for resource use and management. Each village has its own customary norms identifying what can and cannot be done in the forests, as illustrated in Figure 11. Most of the families can collect non-timber forest products, raise animals free-range in certain plots, and have access to some logs for making houses with permission (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

Each village publishes its own customary norms. Through our activities we helped to both formally register and obtain recognition by formal government agencies of each village’s customary norms. We also assisted in setting up wooden boards placed at the front of each village with hand-written rules and norms to inform community members and outsiders of what they can and cannot do to the community forests. Each of the four villages has different wooden boards (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

Figure 11. Our activities helped to set up wooden boards with hand-written customary norms in the villages (Photo: Le)

The differences between villages in their customary norms are found largely in their descriptions of each separate mountain and landscape that each village rests within. The entire H’re community shares a common God or Nature Spirit, or the equivalent. But for eachmountain or forest area, a different local name and local history are associated with the place (CENDI 2015). Members of each community gather to discuss their particular norms for use and management of the area. The establishment and practice of these norms play an important role in the maintenance and conservation of biodiversity. If a need to change these norms arises, community members sit under the guidance of traditional elders and respected village leaders to discuss and also vote upon the changes. The creation of boards listing customary norms is a new innovation for the H’re (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

H’re socio-ecological practices linked to well-being

- Social settings of the H’re community

The H’re live in small groups in a village, often called plấy in the H’re language (Hoang, 2013). In one village, there may be three to four clan families and the associated daughters and sons, granddaughters and grandsons. During the daytime, they call out to each other to go into the forests or the fields together. During the evenings, they gather to drink rice-wine and sing, sharing the details of their lives and work in the fields. Many families still do not have access to electricity. They sit around the fireplace and drink until falling asleep.

- Community-based institutions and the role of esteemed men

In both traditional and present day H’re society, the village, its residential areas forming the core part, are voluntarily self-governed (Hoang 2013; SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017). The self-governing mechanism means that the H’re people pay high respect to the role of traditional leaders and elders—villagers listen to them. Figure 12 depicts an example of a spiritual ceremony where an elder was asked to help convey a family’s message to the Spirit. Each village also has its own headman, in the H’re language called kra plây (Hoang 2013; CENDI 2015). The villagers, whenever facing difficulties including conflicts requiring resolution, seek advice from elders and headmen, who are knowledgeable in the H’re culture, identity, and local wisdom (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

Figure 12. H’re man preparing offerings for a ceremony for cultivating the new rice. An elder man in the community helping the family talk to the Spirit during the ceremony (Photo: Dang)

- Perceptions of values and practical norms concerning the natural landscape

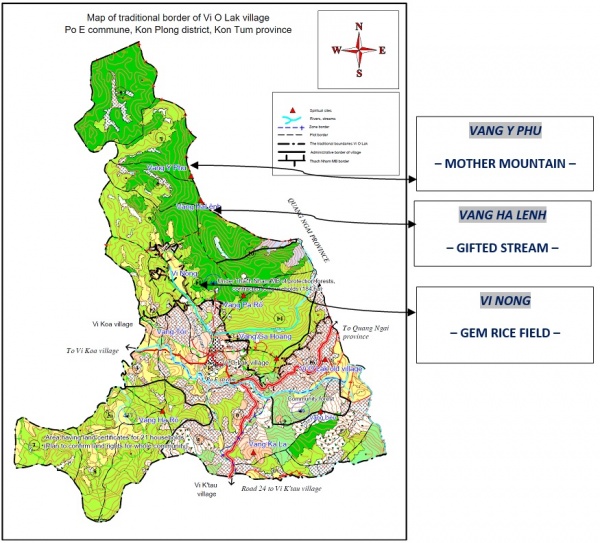

The H’re villagers, through their daily and yearly cycles, pay respect to nature as they conduct their spiritual and material lives (CENDI 2015). Figure 13 depicts a traditional mapping of the different spiritual ecosystems in which the H’re practice ritual ceremonies throughout the year (LISO 2015). Embedded in these customs is a deep commitment to nature and cultural identity preservation. This mapping documentation is a new innovation resulting from our research activities (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

Figure 13. Newly created documentation of the map of traditional borders of one village (Source: LISO 2015)

The Spirit of Vang Y Phu – Mother Mountain: With a height of 1,150 meters, Vang Y Phu is the place the H’re believe the most powerful Mountain Spirit resides. Vang Y Phu is considered to be the spiritual cradle of the entire ecosystem of the village. In the H’re language Vang Y Phu means “Mother Mountain” (CENDI 2015). According to the H’re belief in the Mother Mountain, the Spirit resides in two big old trees (in H’re language Loong Chi Ri and Loong Preo) (CENDI 2015). The Inta bird sings from these trees and its beautiful voice can be heard beyond the mountain. According to customary norms, the H’re can only listen to the Inta bird but are not allowed to sing along (CENDI 2015). Every year, the H’re villagers make a pilgrimage to Vang Y Phu in their traditional clothes bringing offerings. During the pilgrimage, the villagers worship the Mother Mountain spirit and express their admiration, praying for a peaceful, healthy and happy life for all community members.

The Spirit of Vang Ha Lenh – Gifted Stream: Vang Ha Lenh is the second highest hill at 1,070 meters. The combination of Vang Y Phu and Vang Ha Lenh creates the unique scenery and landscape that has inspired generation after generation of the H’re. The villagers described the Ha Lenh stream as a gift from the Mother Mountain, VangY Phu (CENDI 2015). Every year in spring, all the villagers go together to the “Gifted Stream” to hold a ceremony for collecting water, shown in Figure 14, with the women’s group collecting water for their special ceremony.

Figure 14. H’re women collecting water for the special ceremony (Photo: Dang)

This ceremony is an important event for every family in all villages. Both husbands and wives go into the forest to prepare materials for the ceremony. A ritual ceremony to welcome the Water Spirit from Ha Lenh stream into the sacred room of the house is also held at home by each family (CENDI 2015).

The Spirit of Vi Nong rice field – Gem Rice given by “Yang”: The Vi Nong rice fields produce local sticky rice varieties such as H’Roa and Mao Nu. There is also a non-sticky rice species called Jring. All rice species are combined and used for making the special local ghe wine, used as offerings to the Spirits in all rituals and for home consumption (CENDI 2015). As the villagers worship the Spirit of Vi Nong, the rice fields, they also worship the Spirit of the Vang Ha Lenh that provides water to the fields, as well as the Spirit of the Mother Mountain, Vang Y Phu (CENDI 2015). Like the Elder A Xi shared, “rice is a gem given by Yang”. The H’re villagers show their deep gratitude through practicing this annual ritual. The special local ghe wine is hung on the sacred pillar in the sacred room of the house as an offering all year round in the worship of Yang (CENDI 2015).

The local economic system of the H’re community

Up to the present day, most of the livelihood activities of the H’re remain traditional and are primarily a subsistence system based on both livestock and farming. Livelihoods are closely connected to the natural resources provided by the SEPLS. People cultivate and harvest crops including rice production and upper hill cultivation, collect and hunt in forests, rivers and streams, and also utilize other natural resources.

In the upper hills, agricultural crops such as cassava, corn, coffee, certain fruit trees, and some annual plants can be found. Villagers practice mixed planting—in some families they plant sweet potato, taro, yam, sugar cane and banana in separate areas. Production activities are diverse. For forestry species, crops such as cinnamon, hybrid acacia, bamboo, Litsea glutinosa, and also chinaberry (Melia azedarach) are currently grown. There are many local plants and trees of native varieties specific to the local ecosystem that have not yet been fully studied and documented. Agricultural crops and forest species are a mixture of both local varieties and new varieties (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

New varieties are more frequently found for cassava, corn and coffee. Hybrid acacia is exceptional in terms of its extensive planting, up to 145 hectares. According to a report in 2014, only 22.5 hectares were planted with local varieties for all the crops types, whilst 224.4 hectares were planted with new varieties also for all crop types (Po E Communal People’s Committee 2014). According to interviews, new varieties for cassava were introduced in 2014 by the government. Areas for planting the new cassava have increased rapidly in recent years. New varieties of cassava are often planted in the upper hills; the furthest distance would be about a 20 minute walk. All the products from new cassava varieties are sold directly to buyers by villagers (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

For hybrid acacia, cultivation began in 1999 and also came from government introduction. According to interviews, the villagers started planting these crops only from 2004. On average, each family has about 5,000 square meters; with the largest area a family can plant being up to two hectares. Depending on each mountain area and the soil type, villagers may plant acacia on the upper field for the first year, then mix planting with some cassava. Until the acacia fully grow, villagers do not plant cassava. On average, each family has already harvested and sold over two acacia cycles. The manner of harvesting, as well as the ways in which villagers sell their produce, really depends on each separate family. Some harvest first then find their own ways to sell. Some choose to sell acacia right in the forests (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017).

Major external pressures on the landscape and livelihoods

Despite local efforts to culturally and socially maintain the socio-ecological landscapes, there are emerging challenges of great concern. Challenges have largely arisen due to market development associated with policy schemes. Commercial cassava cropping has accelerated due to market demand associated with a policy scheme for E5 bio-fuel development (Viet Nam News 2017), as well as due to the demand for sources of animal feed from small and medium-sized businesses. Areas of production forest cleared to make way for cassava crops were of particular concern in 2016 (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017). Table 1 shows that more areas in the Po E commune are now used for cassava and corn compared to the years 2014 and 2015. In the first six months of 2016, the total land area for cassava and corn had already reached 419 hectares, well above the annual planned limit of only 405 hectares (Po E Communal People’s Committee 2016).

Table 1. Changes over the three types of land use from 2014-2016 in the Po E commune (Po E Communal People’s Committee 2016)

| Land types and areas | 2014 | 2015 | 2016

(early first 6 months) |

2016

(planning for entire year) |

| Hilly areas (largely cassava and corn) | 384 ha | 442 ha | 419 ha | 405 ha |

| Forestland areas (largely production forests such as hybrid acacia, cinnamon, bamboo) | 644.6 ha | 655.6 ha | 655.6 ha |

Commercial cassava varieties, shown in Figure 15, that were introduced along with the use of herbicides, as illustrated in Figure 16, in the earlier years claimed a higher yield. However, in subsequent years these varieties have cost the villagers more whilst health issues have already been observed (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2017). Much is not yet documented, and a more detailed investigation into these issues and impacts is needed.

Figure 15. Clearing of production forests for planting cassava (Photo: Dang)

Figure 16. Herbicides found in one of the villages. These observations are recent. (Photo: Le)

Discussion

Findings have demonstrated that the H’re people continue to perform ritual ceremonies expressing their gratitude towards Nature Spirits and their belief that everything they need to live has been offered to them. Embedded in these beliefs is a unique sense of well-being and inner happiness (CENDI 2015). Their practice of showing respect towards nature may sound merely spiritual, but nevertheless reflects an entire holistic indigenous knowledge system and lifestyle based on the coexistence of both the concrete and the spiritual. The H’re’s continued belief in sacred trees, the Mother Mountain, the Gifted Stream, and also the Gem Rice Fields, illustrates the interconnectedness of their knowledge system and implies the non-opposition of the secular to the spiritual, as well as the non-separation of the empirical and objective from the sacred and intuitive (Nakashima & Roué 2002). These are further reinforced by their wish to protect their natural capital for the long run. Documentation and publication of the H’re people’s practices and links to spiritual entities and the SEPLS are currently insufficient. The need remains to inform the public and concerned stakeholders of the significance of the indigenous knowledge system and its contribution to biodiversity conservation. This is important to the implementation of Article 8(j) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (developed at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992).

Our activities on site aimed to strengthen the livelihood sovereignty of the villages through securing community land titles whilst defending the recognition of customary laws based on resource governance to address emerging challenges (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2018). It is essential for the villages to get land titles for their sacred forests given the following rationale. Vietnam has ambitions of becoming a more developed nation. It is interconnected to the global market and is inevitably affected by the processes of globalization and industrialization. The legal framework has been reworked to give favour to privatization and extraction of local resources. The presence of more firms and businesses in the areas of indigenous ethnic minorities threatens the maintenance of community structures and traditional practices, including spiritual dimensions which are, by nature, the indigenous knowledge system of the H’re people (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2018). Agricultural policies geared towards modernization with hybrid and high-yielding crops and use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides threaten local communities with the loss of local knowledge and know-how and the extinction of local native species. Our work on the legitimate claims to sacred forests of indigenous communities aims to contribute to the conservation of cultural and spiritual uses of species, genetic resources and natural biodiversity (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2014-2018). The underlying spiritual and cultural dimensions expressed in the daily lives of the H’re display the essence of their indigenous knowledge system by which they govern and use resources to the benefit of their own well-being (CENDI 2015). Changes have been observed and mostly are increased awareness and realization by the communities of the value and need for protection of the land and forests against external forces, such as reducing cases of logging. The gradual recognition of their indigenous knowledge and practices is a key part of cultural identity preservation, and self-determination contributes to the overall sustainable management of their natural resources and SEPLS.

Land use change has put pressure on villages, and expansion of commercial cassava cropping at the landscape level is one of the key factors implicated in forest loss (SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance 2016-2018). Whilst protection and support from the government is often very limited (To, Mahanty & Dressler 2016), the expansion of cassava may continue not only to meet increased global demand but also domestic need for E5 bio-fuel. Herbicide use associated with cassava production has already raised concerns both from ecological and social perspectives, although our research activities were not yet able to look into this issue in detail. Community cohesion experienced certain changes as some families have been approached to plant cassava crops, while a few still have not. Other social relationships involved in the cassava production chain also revealed a complexity and degree of dependence (To, Mahanty & Dressler 2016), which could potentially effect a loss of autonomy and self-determination on the part of villagers, as well as a loss of identity and culture. If commercial cassava crops increased to become a dominant landscape, it is not clear how the H’re would tackle this changing socio-ecological landscape (SEPLS) and what role customary law would play in addressing increasing market demand, i.e. more land conversion and increased use of herbicides and complex social relations. For each forest cut down, the multiple values trees have to offer are lost, including ecosystem value. Thus, when trees are cleared to make way for commercial cassava crops, we are turning from the multiple-choice forest ecosystem landscape into an area of no biological or no higher value agricultural land. How can customary laws cope with increased changing landscapes and tackle complex forms of social relationships? A future study to investigate these questions in-depth and compare information with that available for other communities undergoing similar pressures and changes is needed.

Conclusion

The above descriptions have illustrated that the cultural beliefs of the H’re people, practiced regularly and well maintained, are embedded within their own natural landscapes. The socio-ecological connections within the H’re society, whether at the individual or collective level, are both cultural and spiritual connections with the surrounding nature. Our activities to date have added to our knowledge on the human-nature linkage of the H’re people, and given insight into their perspectives as evident in their daily living practices and livelihoods.

Most of the H’re production activities are strongly linked to their socio-ecological production landscape (SEPLS). Likewise, their rituals to express thanks to Nature Spirits imply respectful practices towards nature. Throughout the year, the cultural and spiritual meanings inherently conveyed through all production activities of the H’re are also very significant to the inner happiness and well-being of each individual and the entire community.

Our activities have resulted in the display of customary norms on boards at the entrance of each village and the documentation of traditional mapping. This enhances the ability of the H’re to strengthen their management of the forest and landscape resources (SEPLS), and reinforces their livelihood sovereignty. Most importantly, the H’re indigenous knowledge system and traditional ways of life that go hand in hand with the maintenance of local ecological systems and the conservation of biodiversity have been highlighted.

To cope with ongoing environmental challenges, we together with community members continue to raise these issues and report them to officials at varied levels. Community activities and discussions on the impacts of herbicide use were conducted late 2016. Likewise, more awareness raising and trainings are being conducted in 2017. Empowerment and skills enhancement for young H’re people and intergenerational knowledge exchanges will be conducted in the hope that these young H’re and the entire community will recognize their internal strengths and the unique culture generated from their traditional landscapes (SEPLS). It is hoped that this recognition will be the foundation for their continued well-being and livelihoods. The many valuable insights of the H’re people’s linkage between humans and nature, as expressed through cultural activities and ritual ceremonies associated with such landscapes, should not be further damaged by increased market demand and harmful environmental practices.

References

CENDI, 2015, Livelihood Sovereignty and Village Well-being: H’re people and the Spiritual Ecology. An approach to Biological Human Ecology Theory, Series Three: 2014-2015, Knowledge Publishing House, Vietnam.

Hoang, N, 2013, Typical Traditional Culture of the 54 Ethnic Groups of Vietnam, Social Sciences Publishing House, Vietnam.

LISO, 2015, Newly created documentation of the map of traditional borders of one village, SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance, Hanoi, Vietnam.

LISO, 2016, Map of the Po E commune, Kon Plong district, Kon Tum province, SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Nakashima, D & Roué, M, 2002, ‘Indigenous Knowledge, Peoples and Sustainable Practices’, in Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change, Volume 5, Social and Economic Dimensions of Global Environmental Change, ed P Timmerman, Chichester, pp 314-324.

Po E Communal People’s Committee, Land Department, 2013, First field trip to Po E commune, Kon Plong district, Kon Tum province of the SPERI and the LISO Alliance, (2014), Vietnam.

Po E Communal People’s Committee, 2014, Report on Socio-Economic Development of the last 6 months of the 2014, Po E commune, Kon Plong district, Kon Tum province, Vietnam.

Po E Communal People’s Committee, 2015, Report on Socio-Economic Development of the last 6 months of the 2015, Po E commune, Kon Plong district, Kon Tum province, Vietnam.

Po E Communal People’s Committee, 2016, Report on Socio-Economic Development of the first 6 months of the 2016, Po E commune, Kon Plong district, Kon Tum province, Vietnam.

Po E Communal People’s Committee, 2016, ‘Continued field trips conducted in Po E commune, Kon Plong district, Kon Tum province of the SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance’, (2015, 2016, and 2017), Vietnam.

SPERI, 2016, Status and Changes of Local Rice Varieties: a case study from four villages in Po E commune, Kon Plong district, Kon Tum province, Central Highlands of Vietnam, a small case study report to UNESCO/IPBES, prepared by D Kien, SPERI.

SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance, 2014-2016, Project: Defending Local Knowledge Based Use Rights in Co-Management of Forest and Land in Central Vietnam (2014-2016), Vietnam.

SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance, 2016-2018, Project: Defending Local Knowledge Based Use Rights in Co-Management of Forest and Land in Central Vietnam (2016-2018), Vietnam.

To, P, Mahanty, S & Dressler, W, 2016, ‘Moral Economies and Markets: ‘Insider’ Cassava Trading in Kon Tum, Vietnam’, Asia Pacific Viewpoint, vol. 57, no. 2.

UNU-IAS, Bioversity International, IGES and UNDP, 2014, Toolkit for the Indicators of Resilience in Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS).

Villagers’ stories, 2014-2017. Hand-written notes and recordings from villagers in Po E commune, from SPERI/CENDI and the LISO Alliance, 2014-2017, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Viet Nam News 2017, ‘E5 bio-fuel to replace RON 92’, viewed 12 June 2017, <http://vietnamnews.vn/economy/378123/e5-bio-fuel-to-replace-ron-92.html#1t0EMUWFSiSKF8j3.97>.