Governance-mix for resilient socio-ecological production landscapes in Austria – an example of the terraced riverine landscape Wachau

01.11.2016

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna (BOKU); University of Groningen

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

01/11/2016

-

REGION :

-

Western Europe

-

COUNTRY :

-

Austria (Wachau Region)

-

SUMMARY :

-

Highly valued socio-ecological production landscapes (SEPLs) have to adapt to changing conditions along with globalisation processes in the food and energy sector, demographic and climate change and shifting expectations of food consumers and landscape users. How can different governance approaches contribute to the resilience of a SEPL? This question will be answered for the Austrian case study Wachau, a famous bio-culturally rich terraced wine-growing region along the Danube. This paper illustrates different governance approaches on multiple scales and discusses if and how they contribute to SEPL resilience. The data are outcomes of several studies on land use change, landscape rurality, amenities and governance. The results show that resilient SEPLs need market-driven land use, civil society and state-based governance. In contrast to alpine agriculture where farmers do not have strong bargaining power in marketing, and in milk or beef commodity markets, the Wachau benefits from place-based (i.e. locally branded) food and tourism associated with well-recognised quality and origin labels (e.g. the “Wachau Wein” and the UNESCO World Heritage Site as high quality and identity goods and destinations with a clear geographical link to the landscape). These landscape-based market approaches, supported by a mix of policy and civil society instruments, can ensure the long-term resilience of an authentic SEPL.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Cultural landscape; Landscape governance; Terraced viticulture; UNESCO World Heritage Site Wachau (Austria), Resilience; Protected designation of origin

-

AUTHOR:

-

Dr. Pia Kieninger, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna (BOKU); Dr. Katharina Gugerell, University of Groningen; Prof. Marianne Penker, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna (BOKU)

-

LINK:

-

http://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:5890/SITR_vol2_complete.pdf

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Introduction

[Note: This case study was first published in the Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 2]

Like elsewhere in Central Europe, most of the Austrian landscapes are social-ecological production landscapes, shaped by intense human-nature interactions over centuries. The diversity of Austria’s natural environment has resulted in a broad range of SEPLs linked to local culture, customs and management systems. They are hotspots of biodiversity, providing food and energy, as well as places of spiritual, physical and aesthetical well-being that are important for local identity and pride. Difficult climatic conditions, steep slopes, low soil productivity, outmigration and/or low population density constitute major challenges. Due to these handicaps, SEPLs in less favoured areas are more likely to be affected by land abandonment than elsewhere. Land abandonment, which might be conceptualised as an attractive option for secondary wilderness elsewhere, in Austria and other parts of Europe generates landscape and biodiversity-related concerns in the scientific community and among the public (Navarro & Pereira 2012). Literature reviews identified the following negative consequences of land abandonment: biodiversity loss, increased frequency of fire, soil erosion, desertification, loss of cultural and/or aesthetic values, reduction of landscape diversity, reduction of water provision (Benayas et al. 2007) and an overall undesirable effect on the environment (MacDonald et al. 2000, Estel et al. 2015). Land abandonment is an indicator that some SEPLs are not able to adapt to changing conditions, such as globalised food markets, demand for renewable energy, climate and demographic change or changing expectations of food consumers and landscape users. How can different governance approaches contribute to the resilience of SEPLs? This question will be answered for the Austrian case study of the wine region Wachau, a famous terraced vine-growing area along the Danube. SEPL resilience is understood to be the capacity of a socio-ecological production landscape to absorb or withstand perturbations and other stressors without losing its essential structures and functions (Walker et al. 2004).

Wachau case study

Austria is a very mountainous country: 80% of the federal territory is considered to be agriculturally disadvantaged “less favoured area” (LFA) that is particularly threatened by land abandonment (Hovorka 2006, BMLFUW 2015a). Despite supportive action, extensive land abandonment (particularly loss of grasslands, but also terraced vineyards) has been an issue in the last decades and is expected to continue to be so for the next decades (Hiess et al. 2009).

Vineyard landscapes, like the UNESCO World Heritage Site Wachau, are located in the hilly eastern part of Austria with more favourable soil and climatic conditions. The Wachau is characterised by very high bio-cultural diversity, which results from different habitat and land use types (e.g. alluvial and semi-natural forests, dry grasslands, orchards, vineyards, stone terraces) as well as rich variety in local conditions (e.g. geological and edaphic underground, geographic direction, inclination, relief, climate). While the western part of the Wachau is characterised by a Central European climate with most species of the Central European geobotanical region, in the eastern part, due to the Pannonian climatic influence, xerothermic species can be found (Bundesdenkmalamt 1999). Amongst several IUCN red-listed species, some also play an important cultural role, such as feathergrass that is used as a headdress of the local male costumes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. While bird feathers are used for most of traditional Austrian local costume hats, in the Wachau it is the feathergrass that looks very similar to a feather. The photo shows a proud feathergrass hat owner from Spitz (22.07.2012, Spitz). © G.E.

The Wachau is a historic riverine cultural landscape. While the vast landscape transformation to a terraced landscape originates in the High Middle Ages, wine growing in the Northern parts of the Roman Empire was already prevalent in the first to fifth centuries A.D. Wine-related management practises became rooted in the High Middle Ages, and it is this historical richness that was the basis for the inscription as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000. The Wachau is also part of the EU Natura 2000 network of nature protection areas and since 1994 has been designated within the European Diploma for Protected Areas (AK n.d.-a).

The Danube valley and its tributaries consist of steep slopes with primary rock terraces (inclination up to 50%), explaining its classification as LFA and thus its eligibility with regards to associated EU co-funded compensatory allowances. The landscape is characterised by small-scale vineyards and orchards of mainly apricots. Grasslands occur in the tributary valleys and on softer slopes with less solar radiation. Meadows and pastures are increasingly abandoned since most farmers have given up animal husbandry, and grasslands are overgrown or are replaced by other land uses such as afforestation or Christmas tree plantations.

Abandoned vineyards exist, but are hard to identify in the landscape. Even though they are almost entirely overgrown, the rock terraces and stone walls still exist (Figure 2). New abandonments are rather rare because vineyards are nowadays highly valued, and likewise abandoned vineyards are recultivated when the necessary efforts are reasonable (Figure 3). Altogether, terraced vineyards cover 360 hectares with a total length of 722 kilometres of stone walls (AK 2007).

Figure 2. Old terraces in the forest hills of Arndsorf (04.04.2016). © Kieninger

Figure 3. Reconstruction of terraces in Arndsorf (04.04.2016). © Kieninger

The main income source of the Wachau is tourism and agriculture (Leader-Verein Wachau-Dunkelsteinerwald 2015). More than 90% of the winegrowers belong to the wine cooperative “Domäne Wachau” and deliver at least a part of their grapes or sell them to bigger vintners (Feigl & Peyerl 2011). A small share of vintners solely procure and sell wine. A major portion of the vintners gain additional income from, amongst others, agri-tourism or running seasonal wine taverns called “Heurige” (Figure 4), orchards (Wachau apricots, which are registered with an EU-protected designation of origin), Christmas tree plantations or provision of some other on- or off-farm labour.

Figure 4. Wine taverns are important meeting points for locals and tourists (29.05.2013, Oberloiben). © Kieninger

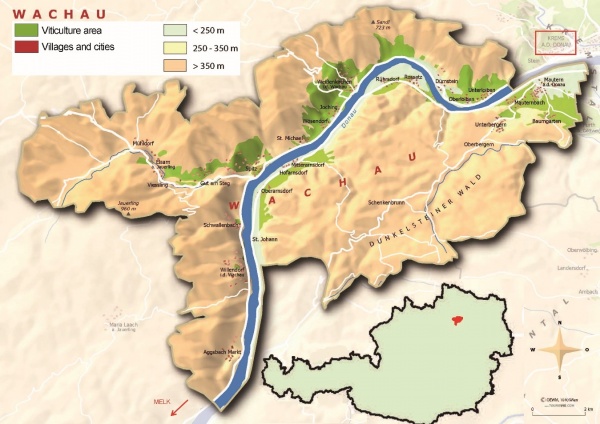

Since the early 1980s wine cultivation area (Figure 5) has remained rather constant, representing 3% of the Austrian vineyard area (BMLFUW 2015b). A total of 600 vintners are cultivating around 1,450 hectares with an average farm size of less than one hectare, which is significantly lower than the average Austrian wine farm size of 4.8 hectares (AK 2007, Feigl & Peyerl 2011, BMLFUW 2015b). Farms are scattered into many small fields (Figure 6 and 7). One third of all Wachau’s vineyards (and therefore all terraced vineyards) have an inclination greater than 25% and accordingly are classified as LFA (AK 2007, BMLFUW 2015a).

The main challenges for the Wachau SEPL are:

- Removal of landscape elements (e.g. fruit trees like peaches between the vine rows, piles of stone, vineyard shelters) negatively impacting the bio-cultural diversity;

- Intensive use of insecticides and herbicides with negative effects on biodiversity and environmental quality;

- Labour and cost intensive production and maintenance of the landscape.

Figure 5. The Wachau (44,684 inhabitants) is a less than 36 kilometre stretch between the cities Melk and Krems (Statistik Austria 2015). The vineyard region (strong green) is smaller than the geographical unit and restricts the usage of the geographical designation “Wachau” wine. © ÖWM, modified by the authors

Figure 5. The Wachau (44,684 inhabitants) is a less than 36 kilometre stretch between the cities Melk and Krems (Statistik Austria 2015). The vineyard region (strong green) is smaller than the geographical unit and restricts the usage of the geographical designation “Wachau” wine. © ÖWM, modified by the authors

Methods

Past and current multi-level, multi-actor governance of the Wachau SEPL

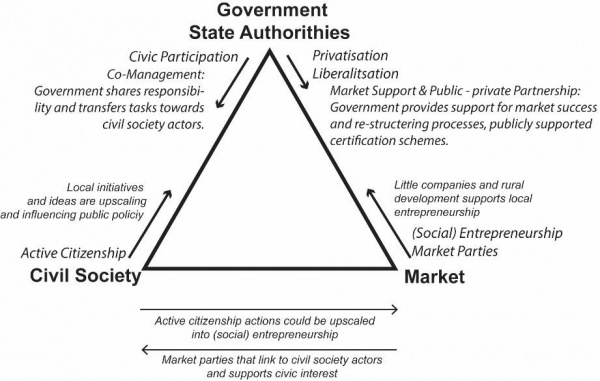

Landscape governance has been and still is a hybrid, linking government, the market and civil society (Figure 8). The multi-level and multi-actor Wachau governance involves different spatial scales that are vertically and horizontally connected via many actors (Figure 9). The decentralisation of governance systems and institutional arrangements has provided a framework for bottom-up, landscape-based and co-designed policies, instruments and implementation actions. However, landscapes themselves have been rarely recognised as administrative units or scales, resulting in an overlap of different administrative units and legal frameworks. In contrast to legally binding acts and strategies, recommendations and guidelines are often based on optional implementation. Lacking direct enforcement power or financial incentives, their implementation is often less attractive at the local level. One interesting example is the management plan for the UNESCO site (currently under elaboration), which has weak immediate legal effect and cannot supersede other policies or implementation measures, thus making its implementation more difficult (Deutsche UNESCO Kommission 2009). Formal protection of cultural heritage is limited to buildings and architectural ensembles, safeguarded by the Monument Protection Act. Apart from agricultural policies and their compensatory payments, landscape and nature preservation policies and spatial planning have largely prevented a loss of ecologically valuable habitats as well as the conversion of agricultural lands into settlements, factories, roads and other infrastructure. These can cause unintended socio-economic effects, like limited job opportunities for younger generations. Whereas farm succession compared to other areas in Austria is not a big issue, jobs outside of agriculture are mostly limited to tourism. Ten of the 13 municipalities are confronted with population shrinkage (Leader-Verein Wachau-Dunkelsteinerwald 2015). The number of elderly people and empty houses is increasing, particularly in the side valleys, alongside the viticulture area. In general the whole Wachau suffers from an ageing population, exacerbated by high real estate and land prices (Weisbier & Zahrl 2013).

Figure 8. Conceptual model of hybrid governance network. © Gugerell, based on Steen et al. 2013

Figure 9. Multi-level network of different landscape related policies, strategies and instruments in the Wachau. © Gugerell

Government-state authorities

The Austrian agri-environmental programme for extensive and environmentally friendly agriculture (ÖPUL)

ÖPUL (since 1995) is an agri-environmental scheme co-funded by the EU that provides financial incentives for pro-environmental and sustainable agricultural production and management techniques (BMLFUW 2015c). The fifth ÖPUL programme (2015-2020) is one measure of the fifth priority of the EU common agricultural policy’s (CAP) second pillar, “Rural Development” (Figure 10). It compensates voluntarily participating farmers (minimum area one hectare for winegrowers) for environmental friendly practices or profit forgone due to extensified production (AMA 2015, BMLFUW 2015c). It offers five different actions in viticulture: a) organic farming, b) erosion control, c) herbicide abstinence, d) insecticide abstinence and e) ecologically valuable areas (e.g. mowing management of grasslands with rare species). In the last funding period (2007-2013), around 57% of the interviewed Wachau vintners participated in the action “erosion control” (Kieninger & Winter 2014). While steep areas of greater than 25% inclination need permanent vegetation cover in the vine rows (only the area beneath the vine can remain open; subsidy: 300-800 EUR/ha), a temporary vegetation cover from November-April and open soils in the rest of the months is allowed on areas with less than 25% inclination (subsidy: 100-200 EUR/ha) (AMA 2015). However terraced vineyards are considered to be erosion control itself (even without vegetation cover), which might explain the measure’s popularity. To avoid water stress in very dry summers, a local management practice is ploughing the vine rows during this period.

Ploughing in general can have a positive effect on biodiversity (open soil supports germination); however, too frequent and deep ploughing harms typical vineyard plants like Muscari or Ornithogalum. The admittance of spontaneous vegetation (in ÖPUL 2007, “natural greening” was accepted as erosion control management) increased the general floristic diversity (Kieninger & Winter 2014).

The funding is coupled with vocational training, which is considered as useful and valuable for the vintners, but should be better tailored to the needs of viticulturists with a special focus on environmental friendly management (ibid.).

Figure 10. Simplified scheme of the new CAP period.

Compensatory allowance for less favoured areas (LFA)

The compensatory allowance for less favoured areas (LFA) is a long-lasting measure of the Common Agricultural Policy (since 1975), in order to aid farmers to maintain the countryside even in areas, where agricultural activity and production is difficult (Agriculture & Rural Development 2009).

To avoid land abandonment of valuable landscapes particularly in mountainous areas, compensatory allowances (3rd priority, 2nd pillar) were given only to livestock farmers for their extra efforts due to steep slopes and harsh climate. In the new CAP programme, these compensatory payments, however, are given to all agricultural use areas in LFA, thus also to terraced vineyards. The funding scheme is linked to farm size and disadvantage and is capped to a max of 70 hectares (LKÖ n.d.).

Maintenance and recultivation of abandoned vineyards and terraces

The rock terraces are the main landscape elements of the Wachau. As long as they are not treated with pesticides, they are also an important habitat for several plant species that can be found normally on rocky terrain, e.g. Sedum album, Veronica prostrata or for reptiles, Lacerta viridis (Kieninger & Winter 2014). Although aesthetically pleasing, production on terraces is more labour and cost intensive and requires additional work for regular maintenance of the stone walls. Abandoned terraced vineyards are quickly overgrown, and recultivation and rebuilding of stone walls require a large effort. CAP provides a set of subsidies for the recultivation of abandoned vineyards and the maintenance and rebuilding of stone walls. Restructuring of vineyards encompasses all necessary activities to re-plant vineyards and adapt them to demand, i.e. changing the vine variety to one that has a higher demand in the global wine market. The amount of the subsidy differs from 9,000 to 13,000 EUR/ha, depending on the location and steepness of the vineyard (more than two-thirds of terraced vineyards in the Wachau have an inclination of greater than 25%). Repairing damaged stone walls or (re)building entirely new stone walls in existing or newly structured vineyards are supported with 91 EUR/m2. Commonly addressed as “dry stone masonry” (historic construction technique), many stone walls are nowadays (re)built or repaired using mortar or faced brickwork, which imitates traditional design techniques to stage a historic landscape visual, but has a much lower biodiversity value.

Since 1997 in the Wachau the restoration and reparation of 20,000 m3 of stone walls have been subsidised (NÖ Landesregierung 1997-2000, Katzmayer & Rennert 2003). These subsidies have mainly targeted demand-oriented production and better integration of production into the global market, but also serve landscape preservation purposes as explained earlier and in Figure 11. Biodiversity is significantly influenced by the type of wall and is much higher with the traditional dry stone masonry compared to the faced concrete brickwork walls. With the traditional dry stone walls, as gaps are filled with soil and humidity enters from the backside, plants can root inside and reptiles and insects can hide inside the holes. Around 150 rare animals and 500 plant species have their habitats there (Kraus 2015).

LEADER strategy

LEADER (6th priority, 2nd pillar) is a hybrid programme linking government, the market and civil society. The overall goal of LEADER is to support endogenous rural development and promote cooperation and measures to strengthen and develop the rural economy and quality of life (Land Oberösterreich 2013). LEADER is based on seven different methodological approaches: a) area-based, b) bottom-up, c) Local Action Groups (LAGs) (consisting of representatives of the local council, diverse interest groups, organisations and engaged citizens from different society sectors), d) innovation, e) integrated and multi-sectoral approach, f) networking and g) cooperation. Fifty-six percent of Austria’s population lives in 77 LEADER regions (budget 246 Mio. EUR), and is organised into Local Action Groups (Weinviertel Ost n.d.). The Wachau (13 municipalities), together with the adjacent Dunkelsteinerwald (4 municipalities), forms one LEADER region with 51,250 inhabitants in an area of 502.92 km² (LEADER-Region Wachau-Dunkelsteinerwald n.d.). LEADER funding calls for proposals from inhabitants and stakeholders that develop creative and adequate solutions for local challenges and serve the enhancement of common welfare. A project selection committee is organised to select convincing proposals, and recommends them to the funding agency for final approval (Land Oberösterreich 2013). Each LEADER region has its own management office for project development and financial administration.

Until recently, LEADER had been strongly focusing on tourism and agriculture: in the last period, 15 to 20% of Wachau vintners received financial support for technical infrastructure or diversification measures, e.g. wine taverns (AK 2007). Different touristic products were developed to create local income and improve the tourism destination (e.g. hiking trails, info-points, the “MyWachau” app providing information on local tavern operating hours, or the “rent-a-wine-maker”, where one can book his/her own vintner for a tour). Courses, including on historic building techniques for stone walls, were also financed via LEADER. Since LEADER generally covers 80% of project costs, the Arbeitskreis (see below) often funds the missing 20% (ibid.). In the new period, the focus has shifted to cross-sectoral and cooperative projects, so that individual farm projects are no longer eligible (Ecoplus n.d.).

Civil society: Working Group Wachau (AK – “Arbeitskreis Wachau”)

The local association AK was initiated by two winegrowers in 1972, aiming to conserve and sustainably develop the Wachau, as well as to oppose the construction of a planned hydropower plant that threatened the unique Wachau-Danube and vibrant viticulture landscape along a free-flowing river (AK n.d.-b). The activities of the AK contributed to the recognition of the Wachau area as a World Heritage Site in the 1990s. The association has 250 members representing different economic, societal and cultural groups in all 13 municipalities, as well as citizens and friends of the Wachau (AK 2015). The AK has three goals: a) conservation of the Wachau in its traditional form, b) maintenance of the scenery and c) strengthening awareness of the values, tradition and history in the local population and among guests (AK n.d.-b). The AK is also active in the implementation of nature conservation projects. It organises volunteers to mow steep grasslands that would otherwise disappear due to the suspension of animal husbandry and with them rare plant species, e.g. feathergrass. Other nature conservation actions include the suppression of alien species (e.g. Robinia pseudoacacia), planting of native species (e.g. Populus nigra) and the promotion of endangered species by various measures (river renaturation projects).

The AK is closely linked to the LEADER programme: on one hand it co-funds LEADER projects, and on the other hand initiates and implements projects. Among Wachau’s inhabitants, apart from civil society organisations and official bodies, it appears that the AK and its work could be better communicated and mainstreamed. In 2016 another NGO “AK Welterbe Wachau” appeared, which is also active in the field of heritage, but is currently focusing on maintaining and protecting historic architectural ensembles (Arbeitskreis Welterbe Wachau 2016).

Market: geographical indication (DOC, PDO) and quality management

Products with geographical indications are traditional products with place-based specific qualities, produced by local farmers. The recognition and protection of the geographical name aims to protect the name from misuse. Consumers are willing to pay more for Wachau wine and apricots, with their quality reputations, than for the same products from elsewhere. The protection of the geographical product name ensures that only local farmers are allowed to use it and that the higher reputation based revenues remain in the region and help to sustain the labour and cost intensive production, and with it the characteristic vine terraces and typical vineyard species.

The DOC label guarantees high quality white wines from the Wachau, exceeding the quality standards and requirements of the strict Austrian wine legislation for high quality wine and meeting the regional terroir characteristics that are written down in the quality policy “Codex Wachau” of the regional association “Vinea Wachau”. In addition, a local brand (Figure 11) is also managed by the Vinea Wachau and can only be used by vintners growing vine in the Wachau, meeting the quality standards of the Vinea Wachau and being a member of this association.

Figure 11. The lizard (Lacerta viridis) and the feathergrass Steinfeder (Stipa sp.) have their habitat in the terraces or rather in the grasslands around. Vinea Wachau uses them as a seal of quality: the “Steinfeder” marks the lightest category of wine, and the “Smaragd” the wines with the highest share of alcohol. © Kieninger (Federgras Setzberg, Spitzergraben, 05.06.2016; lizard, Wagram, 18.04.2012); ©Vinea Wachau (labels)

The spatial and quality restriction of the label unifies the DOC, based at the French Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC), with the German ripeness-based classification scale. Vintners have to apply for the label for every harvest and variety and a jury evaluates and certifies if the wine meets the required quality standards. More than 200 winegrowers are members of the association—most of them anticipating that the geographical indication supports promotion and marketing (Vinea Wachau n.d.). Higher prices compensate for the higher production costs in the steep rock terraces. The label targets high-end markets for a luxury product like vintage wine.

Similar to the DOC label, the Wachau apricot has been protected as an EU protected designation of origin (PDO) and only farmers whose fields are located in the Wachau can sell apricots as “Wachau apricots”.

Discussion

This case study suggests that a hybrid governance approach linking government, the market and civil society can be successful in preserving and developing a SEPL (Figure 9). Co-management approaches where the government shares tasks with civil society actors and farmers fosters shared responsibility between governmental and local scales. The case study shows that active citizen participation can not only influence public policy, e.g. against building a hydropower plant, but also supports local entrepreneurship and new product labels and seals. Market, civil society and governmental approaches converge in instruments that support landscape-based markets (i.e. AOC/DOC, PDO). Collective action, deliberation and trust among the different public and private organisations and groups are important characteristics for local landscape-focused associations such as AK or Vinea Wachau, to foster bottom-up processes and active citizenship.

A diverse mix of multi-level interactions including EU, national, regional and local approaches, as well as a diversity of professional backgrounds, interests and ideas, support local livelihoods and landscape-based development strategies. These landscape-based development strategies contribute to the resilience and long-term viability of authentic, evolving and thriving socio-economic production landscapes in contrast to state controlled, static “museum landscapes” .

Other examples have demonstrated that public subsidies and legislation alone cannot guarantee a SEPL’s resilience, for instance the ongoing abandonment and thereby loss of biocultural diversity of mountain grasslands and dairy farming in the Alpine region (e.g. Holzner (ed.) 2007, Hiess et al. 2009, Kieninger et al. 2011, Kieninger et al. 2015). In the Wachau, subsidies for the stone terraces would not be effective without a well-established wine market. Likewise, even if ÖPUL supports the mowing of ecologically valuable grasslands, they disappear due to the unattractiveness of animal husbandry to the Wachau vintners. For sustainable long-term protection, the combination of different instruments is necessary, as are personal and emotional reasons, e.g. local identity and pride for the landscape. Losing pride or the “degradation of pride” is considered to be the root of depopulation and abandonment (Odagiri n.d., Holzner et al. 2007, Xie et al. 2014).

State intervention and public incentives for strengthening ecological quality

Vineyards can harm the ecological system and the environment, e.g. via negative side effects on biodiversity from insecticides, herbicides or fungicides, or the eutrophication of ground water due to mineral fertiliser. The CAP tries to govern these undesirable consequences by cross compliance (EU and national environmental regulations have to be fulfilled for eligibility of EU co-financed agricultural payments) and voluntary agri-environmental schemes (ÖPUL). Whereas the legal regulations for water and soil protection or nature conservation ensure long-term effects on ecological and environmental resilience by constraining market driven land use, ÖPUL has resulted in short-term effects on biodiversity (e.g. herbicide reduction and temporary vegetation cover) and mid-term effects (e.g. higher amounts of plant species in the organically managed vineyards, see Kieninger & Winter 2014). Long-term ÖPUL effects cannot yet be evaluated because the current programme period has not lasted long enough and data from prior funding periods are too fuzzy due to strong variance in the implemented actions and measures. This case study also shows that the participation in the ÖPUL measures, such as “erosion control” or “integrated production”, does not necessarily reflect a certain ecological attitude of the vintners, but rather a rational cost-benefit trade off. This “subsidy behaviour” means that ecological services are often delivered as long as the payment is available and will stop the moment the funding dries up (Frey & Jegen 2001, Rode et al. 2015). To illustrate: the success of decreased herbicide use in the 3rd funding period was put into perspective when in the 4th period (2007), due to the termination of the subsidy, herbicide use increased so much that it equalled the level prior to the start of the programme in 2000 (Kieninger & Winter 2014). Some interviewed vintners affirm that they expect a similar trend for stone masonry if subsidies for maintenance and rebuilding are lowered or dropped. This “subsidy behavior” suggests two interpretations: (1) agri-environmental schemes encourage utilitarian approaches in governing the delivery of environmental services (and might even crowd out intrinsic motivation for environmental and biodiversity protection (Vatn 2010)), and (2) the programme might have increased ecological literacy among vintners, but apparently as yet has failed in mainstreaming or at least triggering substantial behavioural change towards more sustainable and environmentally friendly management practices.

Market mechanisms as prerequisite for dynamic and authentic socio-ecological production landscapes

A dynamic thriving Wachau SEPL depends on wine and food production that provides livelihoods for local farmers. This case study showed that market mechanisms are successfully deployed in the Wachau: geographical indications and regional branding support stronger collaboration among farmers, tourism and other stakeholders and are therefore adaptive responses in the resource regime in case of disturbances or unexpected impacts (Knüppe & Pahl-Wostl 2011). They have a long-term effect (whereas subsidies’ effects are short-term). As wine is a luxury commodity with a high global demand (Anderson & Wittwer 2013), it is doubtful that the same level of success could be expected in SEPLs that focus on staple food products like milk, corn or rice, and the transferability of the Wachau case study to other areas might therefore not be so easy.

The strong branding through the Vinea Wachau can be regarded as a positive effect for the vintners, and also even for non-members who benefit from higher price levels. Also, the demand for vineyards is increasing, causing less abandonment and recultivation. The risk is that the strong brand and its related success can lead towards a lock-in and hamper experimentation and innovation (Hartmann et al. 2015), which is crucial for the region’s resilience (i.e. the development of new sources of income outside of agriculture, the experimentation with new management practices like organic wine growing, new and/or fungus-resistant wine varieties). The strong specialisation and success in the wine and tourism sector, but also strict interpretation of historic monument protection and building culture (UNESCO, Arbeitskreis Welterbe Wachau), can aggravate regional development and job creation outside the tourism and wine sector. Facing the challenges of an ageing population, demographic challenges are also addressed in the development of the UNESCO management plan.

Civil society as the heart and soul of SEPLs

The Working Group Wachau and the underlying civil society activities played an important role in preventing a hydro-power plant investment that would have tremendously changed the hydrobiological and morphological situation of the Danube region, including both the scenery as well as the identity of the historical landscape. Local civil society is the forum where emotions and moral arguments, such as on the next generation or the intrinsic value of bio-cultural diversity, are shaped, contested and transformed into actual actions, such as protection as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The group had and still has an important role regarding awareness building on the unique SEPL Wachau and is a powerful local stakeholder.

Recently the “old” AK and the “new” AK Welterbe Wachau launched a broader discussion on the future development of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, peaking in a controversial debate on spatial development and historical architectural design (Arbeitskreis Welterbe Wachau 2016). These discourses are conflicting albeit necessary for a shared vision that can be broadly implemented by land users, tourism firms, local governments and the population. Collective action, communication, social capital, social learning and connections to place, activated by self-organisation, seem to support the resilience of socio-ecological systems (Adger 2003, Berkes & Ross 2013).

The success of Wachau’s wines resulted (where possible) in a conversion of many orchards, arable land and forests into vineyards. Grassland management depends on volunteers (organised by the AK and other nature conservation associations, e.g. Lanius). Whether or not this maintenance approach can be considered a long-term sustainable solution is doubtful, because the organisation of volunteers depends on the engagement of a very few active persons.

Conclusion

In the Wachau, different public policies, market instruments and civil society have created a multi-level, multi-actor hybrid governance structure. There is a complementarity between the three domains. Particularly as market-based mechanisms such as geographical labelling and regional branding work very well, policy and civil society need to ensure ecological and social resilience. The market mechanisms support the livelihoods of local vintners and thus the maintenance of the landscape. Active citizenship highlights ecological and socio-cultural priorities, pushes policy and fosters entrepreneurship (i.e. Vinea Wachau). Even though successful—or maybe even because of their success—market-based tools must be accompanied by regulations and governmental policies that mediate societal values, norms and customs. The case study shows that the mix of different push (i.e. market forces, public incentives and civil society engagement) and pull (i.e. regulations and civic control) mechanisms open up an action space to navigate between multiple important goals of SEPLs.

Even if there are some weaknesses in the governance of the SEPL Wachau, such as the abandonment of ecologically valuable grasslands and limited job opportunities outside agriculture and tourism, it can be regarded as an example of a dynamic thriving socio-ecological system with high adaptability and resilience, in contrast to static museum landscapes (Gugerell & Penker 2012) or other rural SEPLs in Austria affected by land abandonment. The multi-level and multi-actor governance network ensures adaptive learning and innovation processes based on multiple sources of ideas and capacities, which hopefully will also ensure the Wachau’s adaptation to future changes and challenges.

References

Adger, WN 2003, ʻSocial capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate changeʼ, Economic Geography, vol. 79, no. 4, pp. 387-404.

Agriculture & Rural Development 2009, Rural development policy 2007-2013. Aid to farmers in Less Favoured Areas (LFA), viewed 21 March 2016, ˂http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rurdev/lfa/index_en.htm˃.

AK – Arbeitskreis Wachau 2015, Der Arbeitskreis Wachau – Die Mitglieder, viewed 27 June 2016, ˂http://www.arbeitskreis-wachau.at/html/akmitglieder.html˃. [in German]

AK – Arbeitskreis Wachau 2007, Unpublished internal documents. [in German]

AK – Arbeitskreis Wachau n.d.-a, Das Europäische Naturschutzdiplom des Europarates, viewed 27 June 2016, ˂http://www.arbeitskreis-wachau.at/html/eudiplom.html˃.http://www.arbeitskreis-wachau.at/html/eudiplom.html [in German]

AK – Arbeitskreis Wachau n.d.-b, Der Arbeitskreis Wachau, viewed 27 June 2016, ˂http://www.arbeitskreis-wachau.at/html/ak.html˃. [in German]

AMA 2015, MERKBLATT – Österreichisches Programm zur Förderung einer umweltgerechten, extensiven und den natürlichen Lebensraum schützenden Landwirtschaf, viewed 21 March 2016, ˂https://www.bmlfuw.gv.at/dam/jcr:05f9058d-f5db-4f61-8469-7d47d971ee8d/Merkblatt_OPUL-2015_Internet_25-03-2015.pdf˃. [in German]

Anderson, K & Wittwer, G 2013, ʻModeling global wine markets to 2018: exchange rates, taste changes and China’s import growthʼ, Journal of Wine Economics, vol. 28, no. 18, pp. 131-158.

Arbeitskreis Welterbe Wachau 2016, ʻBausünde Weissenkirchen: Stellungnahme zum Kurier- Artikel vom 10. Mai 2016, viewed 27 June 2016, ˂http://www.arbeitskreiswelterbewachau.at/bausuende-weissenkirchen-stellungnahme-zum-kurier-artikel-vom-10-mai-2016-2/˃. [in German]

Benayas, JMR, Martins, A, Nicolau, JM & Schulz, JJ 2007, ʻAbandonment of agricultural land: an overview of drivers and consequencesʼ, CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources, vol. 2, no. 057, pp. 1-14.

Berkes, F & Ross, H 2013, ʻCommunity resilience: toward an integrated approachʼ, Society & Natural Resources, vol. 26, pp. 5-20.

BMLFUW 2015a, Bergbauern in Österreich, viewed 27 June 2016, ˂https://www.bmlfuw.gv.at/land/laendl_entwicklung/le-07-13/bergbauern-az/Bergbauern.html˃. [in German]

BMLFUW 2015b, ʻGrüner Bericht 2015 – Bericht über die Situation der österreichischen Land- und Forstwirtschaftʼ, vol. 56, Bundesministerium für ein Lebenswertes Österreich, Wien, viewed 21 March 2016, ˂http://www.lbg.at/static/content/e173427/e182649/file/ger/Gruener_Bericht_2015.pdf˃. [in German]

BMLFUW 2015c, ÖPUL 2015 – the Agri-environmental Programme until 2020, viewed 27 June 2016, ˂https://www.bmlfuw.gv.at/en/agriculture/Rural-development/-pul2015until2020.html˃.

Bundesdenkmalamt 1999, The World Heritage– Documentation for the nomination of Wachau Cultural Landscape, viewed on 10 June 2016, ˂http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/970.pdf˃.

Deutsche UNESCO Kommission 2009, Welterbe-Manual. Handbuch zur Umsetzung der Welterbekonvention in Deutschland, Luxemburg, Oesterreich und der Schweiz, Deutsche UNESCO Kommission, Bonn. [in German]

Ecoplus, n.d., ecoplus Richtlinien für Fördermaßnahmen im Rahmen des Österreichischen Programms für Ländliche Entwicklung / LEADER 2014-2020 in Niederösterreich, viewed on 13 June 2016, ˂http://www.ecoplus.at/sites/default/files/le-leader_richtlinien-2014-2020.pdf˃. [in German]

Estel, S, Kuemmerle, T, Alcantara, C, Levers, C, Prishchepov, AV & Hostert, P 2015, ʻMapping farmland abandonment and recultivation across Europe using MODIS NDVI time seriesʼ, Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 163, pp. 312-325.

Feigl, E & Peyerl, H 2011, ʻDie Sicherung der Traubenlieferung an die Winzergenossenschaft Domäne Wachauʼ, in Prodceedings of the21th ÖGA Jahrestagung on Diversifizierung und Spezialisierung in der Agrar- und Ernährungswirtschaft, Europäischen Akademie Bozen (EURAC), pp. 73-74. [in German]

Frey, BS & Jegen, R 2001, ʻMotivation crowding theoryʼ, Journal of Economic Survey, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 589-611.

Gugerell, K & Petrovics, S 2006, ʻWeinbergslauch und Federspiel. Weingartenvegetation und Wirtschaftsweisen in Spitz und im Spitzer Graben in der Wachau/NÖʼ, Master thesis, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna. [in German]

Gugerell, K & Penker, M 2012, ʻWenn der Wein nimmer ist. Wandel und Permanenz – zum Umgang mit Landnutzungsveränderungen in der UNESCO Welterberegion Wachauʼ, zoll+ Österreichische Schriftenreihe für Landschaft und Freiraum, vol. 21, pp. 40-45. [in German]

Gugerell, K 2012, ʻDas UNESCO Welterbe Kulturlandschaft Wachau im Spannungsfeld von Erhaltung und Dynamik. Zum Verhältnis von Landschaft, Farming Styles und politisch-rechtlicher Steuerung am Beispiel von Spitz an der Donau und dem Spitzer Grabenʼ, PhD thesis, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna. [in German]

Hartmann, S, Parra, C, & De Roo, G 2015, ʻStimulating spatial quality?: Unpacking the approach of the province of Friesland, the Netherlandsʼ, European Planning Studies, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 297-315.

Hiess, H (ed.), Gruber, M, Payer, H, Penker, M, Schrenk, M & Wankiewicz, H 2009, ʻSzenarien der Raumentwicklung Österreichs 2030 – Regionale Herausforderungen & Handlungsempfehlungenʼ, ÖROK Schriftenreihe, no. 176/II, Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz (ÖROK), Wien. [in German]

Holzner, W (ed.) 2007, Almen – Almwirtschaft und Biodiversität, vol. 17, Grüne Reihe des Lebensministeriums, Böhlau Verlag, Wien • Köln • Weimar. [in German]

Holzner, W, Kieninger, P, Jahrl I, Kriechbaum, M & Thaler, F 2007, ʻDie Alm auf dem Hochschneeberg als (Öko-) Systemʼ, in Almen – Almwirtschaft und Biodiversität, Grüne Reihe des Lebensministeriums, ed. W Holzner, Böhlau Verlag, Wien • Köln • Weimar, pp. 219-263. [in German]

Hovorka, G 2006, ʻThe influence of agricultural policy on the structure of mountain farms in Austriaʼ, Ländlicher Raum, Online-Fachzeitschrift des Bundesministeriums für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Umwelt und Wasserwirtschaft, Wien, viewed 27 June 2016, ˂https://www.bmlfuw.gv.at/en/searchresults.html?queryString=less+favoured+area˃.

Katzmayer, H & Rennert, G 2003, ʻBewässerung in Niederösterreich – anlässlich der Fachtagung der DLG-Arbeitsgruppe Feldberegnung im Juli 2003ʼ, Amt der NÖ Landesregierung, St. Pölten, viewed 28 June 2016, ˂http://fachverband-feldberegnung.de/pdf/niederoe.pdf˃. [in German]

Kieninger, P, Holzner, W & Andrianos, L 2011, ʻEine uralte Welt verschwindet vor unseren Augen. Pastorale Landnutzung einst und heute: Über die Almwirtschaft in den Sölktälern und den Weißen Bergenʼ, zoll+ Österreichische Schriftenreihe für Landschaft und Freiraum, vol. 18, pp. 80-86. [in German]

Kieninger, P & Winter, S 2014, ʻPhytodiversität im Weinbau – naturschutzfachliche Analyse von Bewirtschaftungsmaßnahmen und Weiterentwicklung von ÖPUL-Maßnahmenʼ, Ministerium für ein lebenswertes Österreich, Wien, viewed 08 February 2016, ˂http://naturschutz.boku.ac.at/typo3/fileadmin/user_upload/Files/Endbericht_Phytodiversitaet_im_Weinbau.pdf˃. [in German]

Kieninger, P, Penker, M & Maier, V 2015, Mountain pasture management in the Sölktäler Nature Park, Satoyama Initiative, Tokyo, viewed 7 February 2016, ˂https://satoyama-initiative.org/old/en/mountain-pasture-management-in-the-solktaler-nature-park/˃.

Knüppe, K, & Pahl-Wostl, C 2011, ʻA framework for the analysis of governance structures applying to groundwater resources and the requirements for the sustainable management of associated ecosystem servicesʼ, Water Resources Management, vol. 25, no. 13, pp. 3387-3411.

Kraus, D, 2015, Bereits 1.500 Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmer bei Trockensteinmauer-Lehrgängen geschult, viewed 18.07.2016, ˂http://www.noel.gv.at/Presse/Pressedienst/Pressearchiv/117992_Trockensteinmauer-Lehrgang.html ˃. [in German]

Land Oberösterreich 2013, Die Leader Methode, viewed 27 June 2016, ˂http://www.leader.at/leader%20methode.htm˃. [in German]

Leader-Region Wachau-Dunkelsteinerwald n.d., LEADER-Region Wachau-Dunkelsteinerwald, viewed 27 June 2016, ˂http://www.wachau-dunkelsteinerwald.at/leader-region-wachau-dunkelsteinerwald.html˃. [in German]

Leader-Verein Wachau-Dunkelsteinerwald 2015, LAG Wachau-Dunkelsteinerwald – Lokale Entwicklungsstratgeie: Erfolgreiche Frauen und Männer. Begeisterte Gäste. Eine herausragende Kulturlandschaft. Höchste Lebensqualität für Jung und Alt, ˂https://www.google.at/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0ahUKEwiD19jAlMnNAhXhDMAKHTpWC2YQFggfMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.wachau-dunkelsteinerwald.at%2FLES.html%3Ffile%3Dtl_files%2Fdokumente%2F05_strategie%2FLokaleEntwicklungsstrategie_Wachau-Dunkelsteinerwald_150412.pdf&usg=AFQjCNHONgSy28puFgkBnFJnkKB0hHV0ww&bvm=bv.125596728,d.ZGg&cad=rja˃. [in German]

LKÖ n.d., So wird die neue AZ ermittelt, viewed 21 March 2016, ˂https://www.lko.at/?+Ausgleichszulage+&id=2500,,2222946˃. [in German]

MacDonald, D, Crabtree, JR, Wiesinger, G, Dax, T, Stamou, N, Fleury, P, Gutierrez Lazpita, J & Gibon, A 2000, ʻAgricultural abandonment in mountain areas of Europe: Environmental consequences and policy responseʼ, Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 59, pp. 47-69.

Navarro, LM & Pereira, HM 2012, ʻRewilding abandoned landscapes in Europeʼ, Ecosystems, vol.15, no. 6, pp. 900-912.

NÖ Landesregierung 1997, ʻAbrechnung Steinmauern und Böschungsterrassen im Kammerbezirk Langenlois, Mautern, Krems und Spitzʼ, unpublished. [in German]

NÖ Landesregierung 1998, ʻAbrechnung Steinmauern und Böschungsterrassen im Kammerbezirk Langenlois, Mautern, Krems und Spitzʼ, unpublished. [in German]

NÖ Landesregierung 1999, ʻAbrechnung Steinmauern und Böschungsterrassen im Kammerbezirk Langenlois, Mautern, Krems und Spitzʼ, unpublished. [in German]

NÖ Landesregierung 2000, ʻAbrechnung Steinmauern und Böschungsterrassen im Kammerbezirk Langenlois, Mautern, Krems und Spitzʼ, unpublished. [in German]

Odagiri, T n.d., Rural Regeneration in Japan, Centre For Rural Economy – University of New Castle Upon Tyne. Centre for Rural Economy Research Report, ISBN 1 903964 37 7 242 22, viewed 14 June 2016, ˂http://www.ncl.ac.uk/cre/publish/researchreports/Rural%20Regeneration%20in%20Japan.pdf˃.

Rode, J, Gómez-Baggethun, E, Krause, T 2015, ʻMotivation crowding by economic incentives in conservation policy: a review of the empirical evidenceʼ, Ecological Economics, vol. 117, pp. 270-282.

Statistik Austria 2015, Ein Blick auf die Gemeinde, viewed 09 December 2015, ˂http://www.statistik.at/web_de/services/ein_blick_auf_die_gemeinde/index.html˃. [in German]

Steen, M van der, Twist, M van, Chin-A-Fat, N, Kwakkelstein, T 2013, Pop-up publieke waarde, Overheidssturing in de context van maatschappelijke zelforganisatie, Nederlandse School voor openbaar Bestuur. [in Dutch]

Vatn, A 2010, ʻAn institutional analysis of payments for environmental servicesʼ, Ecological Economics, vol. 69, no. 6, pp. 1245-1252.

Vinea Wachau, n.d., Mitglieder, viewed 10 June 2016, ˂http://www.vinea-wachau.at/vinea-wachau/mitglieder/˃. [in German]

Walker, B, Holling, CS, Carpenter, SR & Kinzig, A 2004, ʻResilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systemsʼ, Ecology and Society, vol. 9, no. 2, art. 5.

Weinviertel Ost n.d., Leader in Österreich, viewed 11 February 2016, ˂http://www.weinviertelost.at/was-ist-leader/das-leader-programm/20-jahre-leader-in-oesterreich˃. [in German]

Weisbier, G & Zahrl, J 2013, Gästemagnet stirbt langsam aus, viewed 10 June 2016, ˂http://kurier.at/chronik/niederoesterreich/waldviertel/duernstein-gaestemagnet-in-der-wachau-stirbt-langsam-aus/4.642.815˃. [in German]

Xie, H, Wang, P & Yao, G 2014, ʻExploring the dynamic mechanisms of farmland abandonment based on a spatially explicit economic model for environmental sustainability: a case study in Jiangxi Province, Chinaʼ, Sustainability, vol. 6, pp. 1260-1282.