Fostering a new human-nature relationship in an area devastated by Great East Japan Earthquake in Ishinomaki, Japan

18.01.2023

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

AEON Environmental Foundation

OTHER CONTRIBUTING ORGANIZATIONS

AEON TOHOKU Co., Ltd.

Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES)

DATE OF SUBMISSION

11/01/2023

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Japan

KEYWORDS

Great East Japan Earthquake; A forest of requiem; Volunteers; A continually nurtured forest

AUTHORS

Hideyuki Kubo, IGES

Shigenobu Suzuki, AEON TOHOKU Co., Ltd

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

1. Background

At 14:46 on March 11, 2011, the largest earthquake ever recorded, with a magnitude of 9.0 on the Richter scale, occurred, and together with the subsequent tsunami, caused extensive damage along the Pacific coast of the Tohoku region in Japan. The human casualties, as reported by the National Police Agency on April 10, 2015, were 15,891 dead and 2,579 missing nationwide. Miyagi Prefecture accounted for about 60% of the victims, making it the prefecture that suffered the most damage.

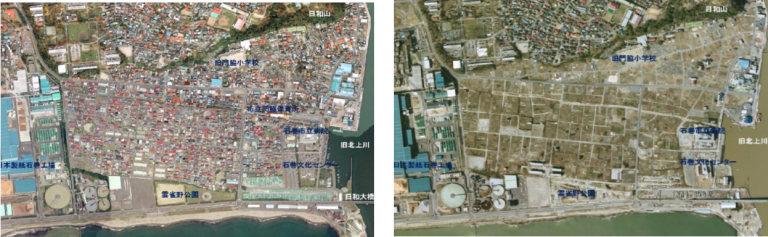

Ishinomaki City, located in the northeastern part of Miyagi prefecture, recorded a seismic intensity of 6 on the Japanese scale. The maximum tsunami height was at 8.6 meters, inundating the entire central city area. The city accounts for about 30% of all the victims in Miyagi, making it the largest affected area in the prefecture. Among them, the Minamihama district (see Figure 1 below), an urban area located at the mouth of the former Kitakami river, was one of the hardest hit areas in Ishinomaki, with more than 400 people killed by the tsunami and the spread of fire. The earthquake and tsunami caused the ground to sink, and parts of the area have become marshland. The Minamihama district was the area damaged by a combination of earthquake, tsunami, fire, and land subsidence, making it a representative location devastated by the Great East Japan Earthquake.

The government of Ishinomaki City compiled and published the Basic Plan for Earthquake Disaster Reconstruction in December 2011. In the plan, the construction of coastal seawalls along coast lines and of high embankment roads at inner part behind coastal walls is designed, and areas between coastal seawalls and high embankment roads are prohibited for human settlements due to high risk of tsunami inundation. The Minamihama district is part of such prohibited areas of settlements. Through the compilation process of the Basic Plan, an idea naturally emerged that a park and a forest of remembrance would be appropriate land use for the prohibited area of settlements in the Minamihama district for the future in order for Ishinomaki citizens and visitors from Japan and all over the world offer tributes to the souls of the victims while at the same time, thinking about living in harmony with nature. Similar ideas were also proposed through citizen workshops. The Basic Plan thus accommodated the policy, namely, “A park with a forest of remembrance for all lives lost in the disaster, and a multipurpose plaza will be developed as a symbol of earthquake recovery” as future land use of the Minamihama district.

At the national level, Japan’s government set up the Reconstruction Design Council in response to the Great East Japan Earthquake and submitted its report “Towards Reconstruction – Hope beyond the Disaster” to the Prime Minister in June 2011. The report adopted seven principles for the reconstruction framework, and the principle one says “For us, the survivors, there is no other starting point for the path to recovery than to remember and honor the many lives that have been lost. Accordingly, we shall record the disaster for eternity, including through the creation of memorial forests and monuments…” In January 2012, the government initiated a discussion process about reconstruction memorial parks in order to mourn and remember the souls of the victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake, to pass on the records and lessons of the disaster to future generations, and to convey a strong will for recovery to people in Japan and abroad. They then came up with an idea that the creation of parks should be led by local governments with the financial support from the national government. In Miyagi, it was agreed that a reconstruction memorial park was to be established in the Minamihama district, as suggested by Ishinomaki, and discussions on a basic concept for the proposed park started in October 2013 as a collaborative process among national, prefectural and city governments.

This paper aims to describe how stakeholders are working hard to enable a new human-nature relationship to emerge in the Minamihama district through a reconstruction process from the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami disaster. It starts with the historical overview of the Minamihama district, and is followed by the description of designing and developing a forest of requiem. The paper also looks into institutionalizing a mechanism for sustainability in managing the forest, and considers actions taken by the AEON Group in supporting the establishment of the reconstruction memorial park and the forest of requiem.

2. Socioeconomic and environmental characteristics of the Minamihama district

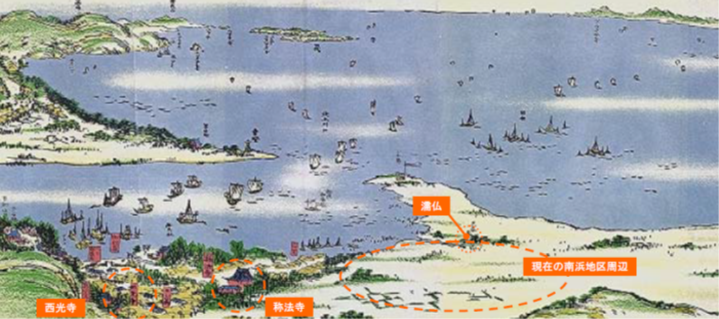

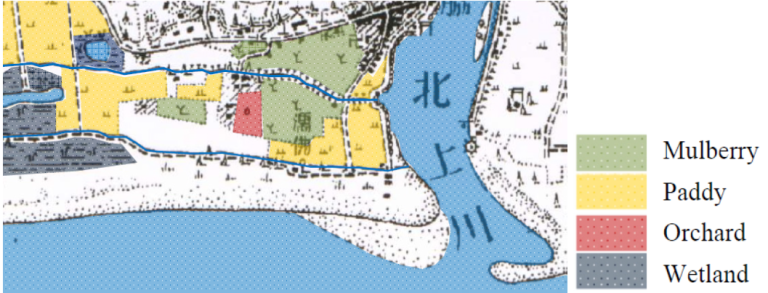

Surrounded by the sea, Ishinomaki was blessed with abundant marine resources, and as can be seen from the many ruins, people have lived a rich life in the area since ancient times. The Kitakami River, the longest river in the Tohoku region, runs through the center of the city. The western side of the river is mostly rice fields with fertile soil. On the east side, on the other hand, there are mountains and a ria coastline, with little flat land. The Minamihama district is a low-lying area at the mouth of the right bank of the old Kitakami River with an elevation of about 1m. To the north of the area lies Mt. Hiyoriyama, which rises 56.4 m above sea level. It is said that at the end of the 12th century, a castle was built on Mt. Hiyoriyama. In the 16th century, a canal was constructed at the northern part of the district that linked the Kitakami River to the west ward and was used to transport rice. At that time, there were still no residents in Minamihama, which as covered in pine forests, sand dykes and wetlands. Figure 2 is a picture painted in around 1852. The painting shows a settlement area with temples but no houses in the Minamihama area, which indicates the district was not suitable for settlement and cultivation. Cultivation of the land began about 100 years ago, resulting in a mixture of various land uses. According to a map of the time (see Figure 3), dominant land uses were for mulberry fields at slightly elevated area and for paddy fields in wetlands. Houses were sparsely located.

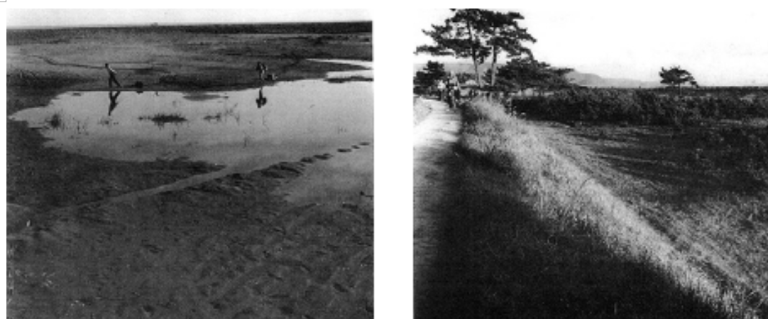

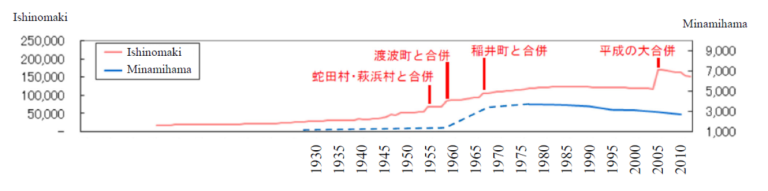

In the 1940s, the construction of a pulp mill near Minamihama led to the construction of housing for employees through the conversion of natural areas. However, some wetlands and pine forests still remained (see Figure 4). Rapid changes occurred after 1964 when Ishinomaki City was designated as a new industrial city. The urbanization of the Minamihama district progressed and natural landscapes began to disappear. Figure 5 clearly indicates the rapid increase of the population that led the land conversion of the district during 1960s.

The earthquake and tsunami of 2011 totally transformed the urban landscape in Minamihama (See Figure 6). Houses and buildings disappeared and wetlands, one of original land types in the district, emerged as the land surface had partially subsided

3. A forest of requiem: Principles, design and institutional arrangements

3.1 Principles and design

The collaborative work between the national, prefectural, and municipal governments that began in October 2013 provided an opportunity to come up with a concept and design for a reconstruction memorial park in the Minamihama district. Their ideas on the initial plan for the park space were to accommodate: (i) a place of mourning and remembrance, (ii) a place to pass on lessons learned, (iii) a symbolic place of reconstruction, (iv) a place to ensure the safety of visitors, and (v) a place for participation and collaboration among diverse stakeholders. The concept of “a symbolic place of reconstruction” indicates that a variety of stakeholders collaborate to produce seedlings of local species and plant them, and then create a forest that is nurtured through the threads of life over time. The most important point of the concept is not simply to create a forest, but to be sensitive to the fact that a forest is nurtured by life, and that it is necessary to care for and support the growth of the forest over time.

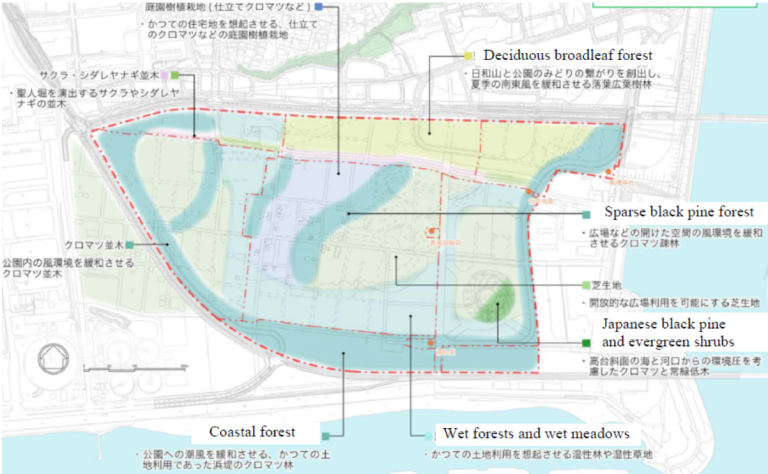

In order to materialize this concept in Minamihama, a series of discussions for designing and planning of the memorial park were carried out through a collaborative process, and the following principles and design on the forest development were proposed: first, the forest will be nurtured in the footsteps of local ancestors who were involved with nature, with the aim of restoring and creating a nature and environment that are unique to the region, and creating a rich and beautiful scene that makes people feel happy. Second, as part of the forest development, pine groves that once existed and are still remembered by the local people will be restored. Figure 7 shows the design of forest types to be developed in the memorial park. The area of the reconstruction memorial park is about 38.8 hectares, of which about half of the land is devoted to forestation. A brief outline of these forest types is as follows:

- Coastal forest:

Japanese black pine forest on the beach bank, former land use that moderates sea breezes into the park, with seasonal colors unfolding in the bright forest.

- Wet forests and wet meadows:

Inaccessible sanctuaries with wet forests and wet meadows that give a reminder of former land use, and a variety of water surfaces and wetlands that are home to a variety of creatures. Alder and willow are among the main species.

- Japanese black pine and evergreen shrubs:

Both Japanese black pine and evergreen shrubs are introduced considering environmental pressure from the sea and estuary on the upland slopes. One key evergreen shrub is the Japanese camellia. Species to be planted include black pine, red pine, shrubby bush-clover, oak, torch azalea, and hill cherry.

- Sparse black pine forest:

Sparse black spruce forest that moderates the wind in open spaces, and a bright forest floor with a clear footing that allows for various activities in the forest.

- Deciduous broadleaf forest:

A deciduous broadleaf forest that creates a green link between the forest on Mt. Hiyoriyama and the park, thereby mitigating the southeasterly summer winds. A bright forest that is home to a variety of woodland creatures. Oak, carpinus, wild cherry tree, fir and cornus are among main species.

3.2 Institutional arrangements

In order to realize the above principles and design, the collaborative process between the national, prefectural and municipal governments identified a two-tiered management and operation system, one in which the government directly controls the forest development and maintenance, and the other in which citizen groups play a central role in promoting activities.

Activities under the direct control of the government are centered on infrastructure development, such as the development of land for forestation. To this end, the government has been placing orders with contractors to carry out construction work. From April 2021, Miyagi Prefecture has appointed a designated manager for the reconstruction memorial park, who will be responsible for routine tree maintenance and management work as a project ordered by the government. Meanwhile, since the basic idea of forestation is not simply to create a forest, but “to be sensitive to the fact that a forest is nurtured by life, and to care for and support the growth of the forest over time,” and since it is based on the participation and collaboration of various stakeholders, a mechanism for citizens’ groups to become involved in park operations was discussed. In October 2016, 17 citizen groups endorsed the establishment of a study council looking into participatory operation for the reconstruction memorial park. The study council established subcommittees for civic use, for passing on memories and lessons, and for forestation. The study council was reorganized as a participatory management council in February 2021. The main activities of the participatory council were defined as memorial service, passing on memories and lessons learned, and forestation. Regarding forestation, the participatory council is permitted to implement some of the projects ordered by the government in consultation with the designated manager and can receive compensation for their work.

This management and operation system of forestation through collaboration between the designated manager and the participatory council has the following advantages. First, maintenance and management costs can be borne by the government-ordered project, thus avoiding the risk of neglect due to lack of funds. Second, the engagement of forestry experts will ensure the provision of expert knowledge with regard to maintenance and management. Third, since the participatory council can implement some of the projects ordered by the government, daily communication between the designated contractors and the participatory council can be promoted. However, one critical issue is that since there are two organizations, problems with coordination between them could hinder the maintenance and management of the forestation itself. However, this risk can be considerably minimized by creating the aforementioned mechanism for communication between the two parties.

4. A forest of requiem: Forestation practices

4.1 Producing seedlings of native species

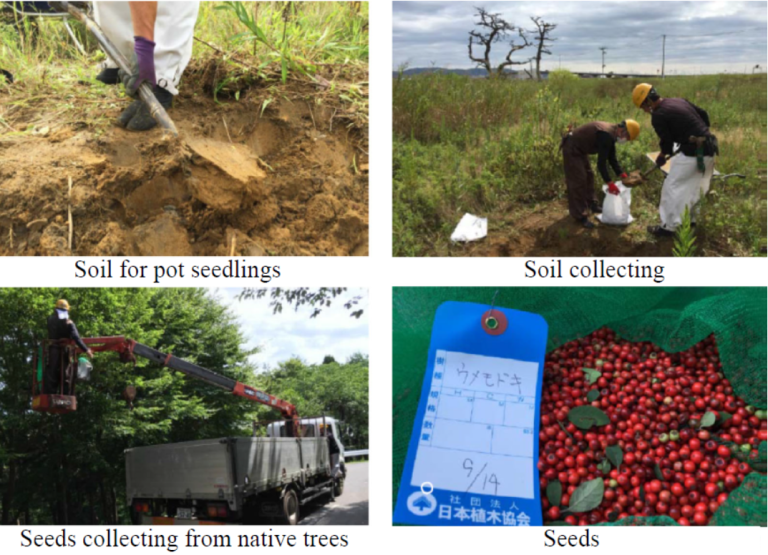

The basic policy of the forestation project is to restore and create unique nature and environment in the district, and to include pine groves that are part of people’s memories. For this reason, the project is working to collect seeds locally and grow them into seedlings. Figure 8 shows a photo of soil for pot seedlings being collected in the park grounds and seeds being collected from native trees in the surrounding area.

In addition, citizen groups are collecting seeds in forests near Minamihama with the help of volunteers. Figure 9 is a satellite image of the area around Minamihama. The narrow strip of green space just north of Minamihama is the Mt. Hiyoriyama forest, and the hills to the east across the Kitakami River make up the Makiyama forest. The citizen’s group “Kokoro-no-Mori”, as a member of the participatory council, has been collecting seeds from Mt. Hiyoriyama and Makiyama forests and began growing seedlings in a greenhouse nursery set up in the northern part of the Minamihama district in the fall of 2014. In 2014, the water supply to the Minamihama district had not been restored, so the founder of Kokoro-no-Mori filled buckets with water at his home and carried them to the greenhouse nursery in Minamihama to water the seedlings. Later, in the fall of 2016, a study council was formed, and in 2017, the greenhouse nursery for seedlings was relocated to an area inside the memorial park, where seed collection from the forest and seedling production continue.

4.2 Trial planting

Because the Minamihama district was inundated by the tsunami, and because the land use prior to urbanization was pine forests, erosion control dikes and wetlands, rather than a forested area, trial planting was conducted prior to full-scale planting. The black pine and red pine are growing well, and only a few of the other tree species are not growing well. However, it was observed that herbaceous plants invading from the outside thrived and shaded the seedlings and saplings, confirming the need for weeding work.

4.3 Tree planting by volunteers

The participatory council, established in October 2016, began considering the first tree planting activities in May 2017. Since this was the first attempt, it was decided to limit the call for tree planting volunteers to former residents of the Minamihama district as well as neighborhood associations, schools, and businesses in the vicinity of the memorial park, and the first tree planting activities were held on September 23, 2017. There were 523 participants and approximately 2,400 seedlings were planted. Thirty-nine different species of seedlings were planted, including black pine, red pine, shrubby bush-clover, oak, torch azalea and hill cherry. Since then, the tree planting activities have been held annually as follows:

2018: 400 people, 3700 trees

2019: 800 people, 7800 trees, 20 species

2020: 100 people, 10500 trees, 16 species

2021: 1100 people, 21500 trees, 16 species

In addition to holding tree planting activities, people from all over Japan, especially from schools, come to plant trees in the memorial park, and the council is responsible for the preparatory work. A total of 100,000 trees are expected to be planted, of which approximately 70% have been planted to date.

4.4 Institutional development to support practice

In sub-section 3.2 above, it was pointed out that the participatory management council can implement some of the projects ordered by the government, thereby promoting daily communication between the designated manager and the council, and minimizing the risk of any problems occurring. Both parties are making efforts in this matter. The citizens’ groups themselves have developed their own expertise and have been designated to take on the role of designated manager, thereby further enhancing the sense of unity between the designated manager and the participatory council. The initiative was taken by a professor at the University of Hyogo, who was involved in the reconstruction efforts following the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995.

The professor was involved in forestation activities for the memorial park as a volunteer, and at the same time, he participated in discussions as an expert in the collaborative process among the national, prefectural and municipal governments regarding the establishment of the reconstruction memorial park. His experience in reconstruction activities after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake made him keenly aware of the dilemma between the need to continue reconstruction activities and the declining level of interest in reconstruction both inside and outside of the devastated area. Therefore, he thought that a citizens’ group engaged in forestation activities could be entrusted by the government as a designated manager for a medium- to long-term project, which would maintain the motivation to continue implementing activities. However, it was difficult for a citizens’ group to win the bidding competition alone, so the professor suggested to form a joint venture (JV) with a company that had abundant experience in the reconstruction business. As a result, in December 2020, the JV team was selected as a designated manager by the prefectural and city councils. Although the civic groups involved in the JV were not part of the participatory management council, they were very close to council member organizations, which made coordination between them much easier.

4.5 Creating a continually nurtured forest

When the professor first became involved in creating the forest in the memorial park, he proposed to citizens’ groups in Ishinomaki that instead of buying seedlings and planting them, they should grow seedlings from local seeds and acorns and continue to nurture the forest after planting, thereby regenerating the local forest in both name and reality and turning the forest and the people involved in its regeneration into a symbol of reconstruction. The citizens’ groups agreed to his proposal and began to work on forest development from scratch with their own hands.

Initially, the founder of the aforementioned “Kokoro-no-Mori” carried water in a bucket from his home to the greenhouse nursery in the Minamihama district to water the growing seedlings. Once a study council was established and tree planting activities were held, inquiries began to come in from schools and organizations not only in Ishinomaki City and Miyagi Prefecture, but from all over Japan. Many people came to Minamihama wanting to make even a small contribution to the reconstruction of the disaster-affected district.

Since the planting work is expected to be completed in a few years (see Figure 11), the next step is to create a system that will allow people to continue to nurture the forest. What is important is to create an environment where people who come to Minamihama and participate in various activities to nurture the forest can enjoy and feel attached to the area. To this end, after the tree planting is completed, a system will be created in which people can enjoy various events such as an open market and wood workshops using wood from thinned forests, while clearing underbrush, pruning, thinning, and other work to experience the forest and its seasonal flowers with all five senses. In order to continue devising ways for people to nurture the forest in the future, efforts are also underway to develop human resources who will be responsible for the participatory management council.

4.6 Involvement of the AEON group

Since 1991, AEON Co., Ltd. has conducted a program to involve its customers in planting trees on the premises of new stores when they open. This program is carried out in the hope that the stores will take root and become a community space for local people, and that the spirit of nurturing greenery will then spread throughout the world. After the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, the company has also been committed to tree planting activities for reconstruction in the affected areas. In Ishinomaki City, 1,600 people participated in the planting of 15,000 trees in the western part of the city in November 2012. Among the volunteers who planted trees at that time was a former resident of the Minamihama district and a representative of “Kokoro-no-Mori,” a civic organization, who would later lead activities to create a forest for the remembrance of the souls of disaster victims at the reconstruction memorial park. He consulted with AEON staff regarding tree planting in Minamihama, which led to AEON donating a greenhouse to the Kokoro-no-Mori in 2014, to be used as a nursery for seedlings. The greenhouse enabled Kokoro-no-Mori to collect seeds and acorns from the Mt. Hiyoriyama and Makiyama forests in the fall of 2014, grow them for seedlings and then plant them. Since then, AEON has provided support for every tree planting activity, and the AEON Environmental Foundation took over the tree planting support from 2019.

To create opportunities for children to participate in tree planting activities, AEON Cheers Club also participates in tree planting activities. AEON Cheers Club is an eco-friendly club that provides learning experiences and hands-on opportunities for elementary and junior high school students. Local elementary and junior high school students living near each store meet up about once a month and engage in various activities related to “environment” and “community” such as environmental conservation and agricultural experience, with store employees serving as coordinators. For the memorial forest in the reconstruction memorial park, seedlings are grown from local seeds and acorns, and the forest is continuously nurtured after it has been planted. This message is conveyed to the participants at a tree planting ceremony by the participatory council, the organizer of the event. Therefore, through tree planting activities, participants are reminded that the seedlings have grown from seeds and acorns, and that these seedlings will grow into a large forest over a period of 20 to 30 years or more. In fact, one of the junior high school students who participated in the tree planting activities commented, “After participating in the tree planting activities, listening to stories, and actually planting trees myself, I was able to look at another forest and think, ‘Oh, trees can be cut down from this forest for timber’ “.

5. Looking to the future

Initially, creating a forest in the Minamihama district consisted of one single volunteer watering seedlings by hand. Later, a council was established with citizens’ groups, and then tree planting activities were held, where volunteers began actually plant the trees. In particular, volunteer tree planting widens the ties with a diverse range of stakeholders, with participation by schools and companies from all over Japan, as well as NPOs from overseas. Meanwhile, although not directly involved in the work at the memorial park, the national, prefectural and municipal governments have been supporting the reconstruction and creation of a forest in the Minamihama district since the beginning.

While various stakeholders are working together to create the forest, it is noteworthy that although the government owns and is responsible for the management of the reconstruction memorial park in the Minamihama district, civic groups have consistently taken the initiative in creating the forest. While the government bears the budgetary burden, citizens come up with ideas for forest creation, and they put their ideas into practice in cooperation with various people in Japan and abroad. The process of creating a forest in Minamihama functions well, with all stakeholders aware of their respective roles, cooperating with each other while keeping in mind the overall purpose.

More than 10 years have passed since the unprecedented earthquake and tsunami, and the initial phase of forestation and development of the reconstruction memorial park is almost complete. In order to build a new relationship between people and nature that will support the growth of the forest over time, those involved in creating the forest have begun working to develop a sustainable system. They create opportunities for more citizens to participate in the project and develop human resources to think about and prepare for such participation. Reconstruction of the Minamihama district of Ishinomaki city is progressing steadily as people nurture the forest of remembrance.

Acknowledgement

We thank Yasushi Kotouno, Mr. Hiroshi Kameyama, Ms. Ayano Onki and Ms. Onodera for their generous cooperation to our study. We also thank the AEON Environmental Foundation for its support in conducting the survey.

References

AEON Tohoku (2021) Environment and CSR activities.

https://aeontohoku.co.jp/pages/csr-top

Digital National Land Information (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Japan). https://nlftp.mlit.go.jp/ksj/index.html. Downloaded on 27 August 2022.

Hirata, F (2021) Long-term reconstruction support for local self-reliance: A case of citizen’s forestation in the reconstruction memorial park in Ishinomaki city. https://www.awaji.ac.jp/gs-ldh/project/teachers-column/hirata2021-07

Ishinomaki city (2011) Basic Plan for Earthquake Disaster Reconstruction.

Ishinomaki Minamihama Tsunami Memorial Park (2022) About the park. Downloaded from https://ishinomakiminamihama-park.jp/about/

Reconstruction agency, Miyagi prefecture and Ishinomaki city (2015) Basic plan for the Minamihama reconstruction memorial park in Ishinomaki city.

Reconstruction agency, Miyagi prefecture and Ishinomaki city (2014) Basic design for the Minamihama reconstruction memorial park in Ishinomaki city.