Ensuring conservation, good governance and sustainable livelihoods through landscape management of mangrove ecosystems in Manabí, Ecuador

30.10.2018

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION

-

Fundación para la Investigación y Desarrollo Social (FIDES); Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES); Conservation International Japan

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION

-

30/10/2018

-

REGION

-

South America

-

COUNTRY

-

Ecuador (Manabí Province)

-

SUMMARY

-

In the area at the mouth of the rivers Chone and Portoviejo, which consists of mangrove forest, islands, beaches, wetlands and saltwater areas, and incorporates the dry tropical forest of the Bálsamo Mountain Range, local communities have been living on fish, crustaceans, shellfish harvesting and agriculture. However, harvesting has been significantly reduced due to sedimentation and pollution, mainly caused by the chemical residue of agricultural and shrimp farming activities. The dry tropical forest faces a reduction of its area due to urbanization and the expansion of agricultural areas. Communal organizations promote sustainable activities devoted to restoration and conservation of the ecosystems through mangrove and dry forest species reforestation. Improvement of local governance has resulted in their territories becoming protected areas and recognized by the National System of Protected Areas (SNAP). Because the economic livelihoods of the communities depend on healthy ecosystems, sustainable activities such as ecotourism, artisanal salt extraction, and artisanal fishery and harvesting have been developed. The communities have applied the Indicators of Resilience tool to assess their Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) to determine whether these socio-economic activities can occur while maintaining the integrity of the ecosystems in the SEPLS. Besides establishing a baseline to quantify the progress of the resilience conditions, the resilience evaluation allowed participating local communities and organizations to develop a work plan that incorporated these actions. As a result, it was concluded that the resilience evaluation helped the local communities and organizations to 1) share knowledge on strengths and weaknesses of the SEPLS; 2) provide opportunities for the debate and analysis of SEPLS between members of the communities; 3) develop priority action plans to strengthen the resilience of the SEPLS; and 4) rethink and recognize how the project would help to address key threats and weaknesses.

-

KEYWORD

-

Landscape approach, mangrove ecosystem, livelihoods improvement, strengthening governance, resilience

-

AUTHOR

-

Jairo Díaz Obando (FIDES), María Dolores Vera (FIDES), Ikuko Matsumoto (IGES), Devon Dublin (Conservation International Japan), Yoji Natori (Conservation International Japan), Andrea Calispa (FIDES)

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

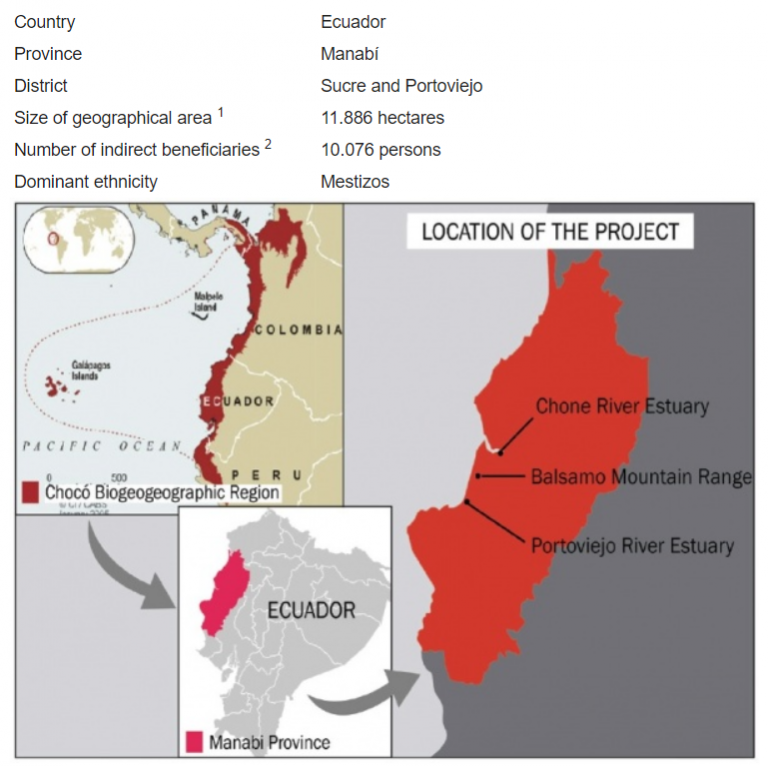

Figure 1. Map of the country and case study of FIDES’s project site Note: Data for Map of the country and region from CI/CABS (2005)

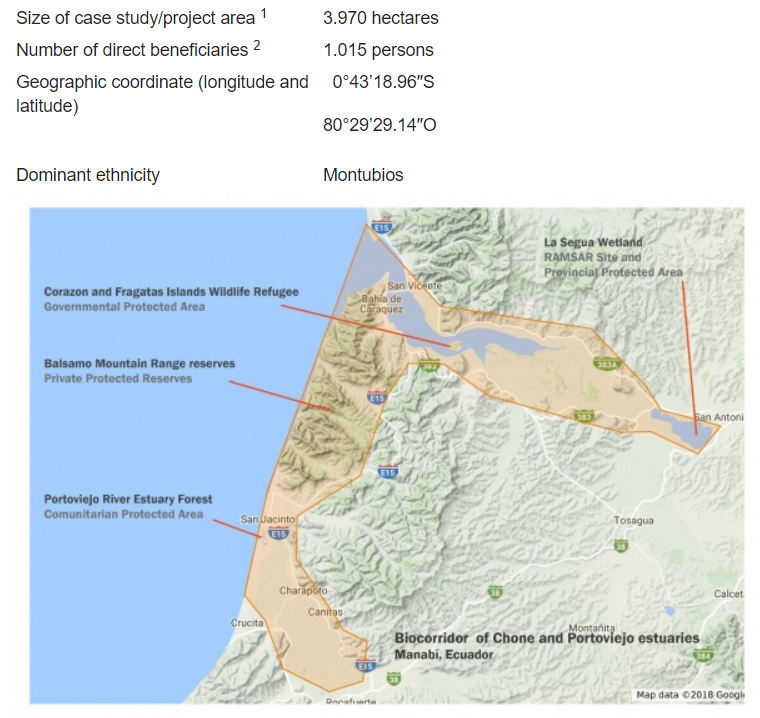

Figure 2. Land use and land cover map of case study site Note: Data for Micro Map of study area elaborated for the present article.

Introduction

Study site

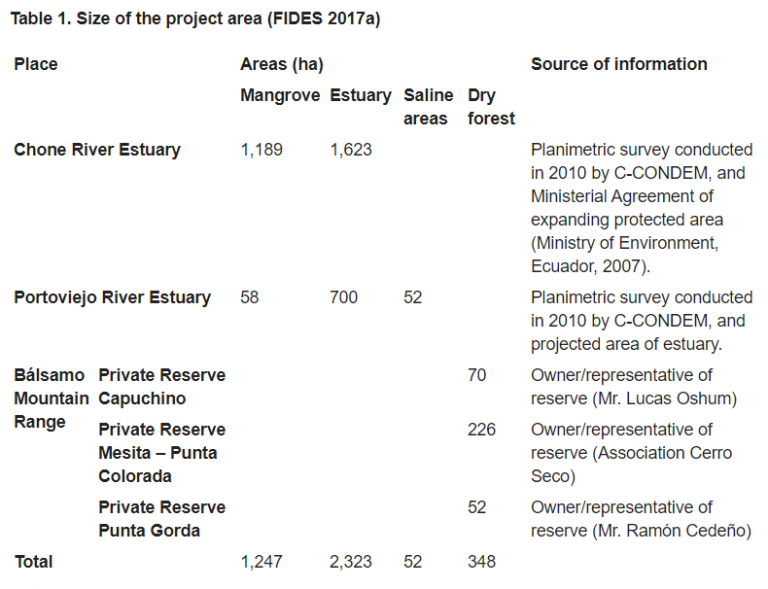

Mangroves are considered one of the world’s most productive ecosystems, providing important economic, cultural, and social services for the various communities settled around them (Ong 1982; Berger, Smetacek & Wefer 1989; Bunt 1992, Kathiresan & Bingham 2001). The study area is a mangrove ecosystem, production landscape and seascape, located within two estuaries, the Chone River Estuary and Portoviejo River Estuary of Manabí Province, Ecuador, and the dry forest of the Bálsamo Mountain Range between these estuaries (Fig. 1, 2 and Table 1).

The Chone River Estuary drains the area of San Vicente surrounding the islands of Corazón and Fragatas, which are wildlife sanctuaries of estuarine islands full of mangroves and a state-owned protected area. The Chone river converges with the Carrizal river creating the La Segúa swamp, a designated RAMSAR site. This fresh water wetland possesses an exceptional richness of avifauna, with a bird count over 190,000, making it a true coastal bird sanctuary (López & Gastezzi 2000).

The Portoviejo River Estuary is shaped by a mangrove forest, salt evaporation ponds (salt pans), beaches, and is the product of the confluence of the sub-basins of the Portoviejo River and Estero Bachillero. Total coverage of the mangrove forest is 57.72 ha, where 19.23 ha is in the San Jacinto community (from Charapotó village) and 38.49 ha in the Las Gilces community (from Crucita village). Regarding flora and fauna, according to Vaca and Piguave (2012), there are 75 species of phytoplankton and 17 species of higher plants in the mangrove forest at the Portoviejo River Estuary. Among these, there are four reported mangrove species: white mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa), buttonwood or button mangrove (Conocarpus erectus), black mangrove (Avicennia germinans) and red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle). This location was declared a communitarian protected area in 2011.

The Bálsamo Mountain Range is made up of approximately 9,500 hectares of dry tropical forest, very-dry tropical forest, and spiny tropical shrubland, located in the central part of Manabí Province, north of the communities of San Clemente, San Jacinto and Charapoto. The Bálsamo Mountain Range presents a wide number of endemic species of deciduous forest remnants including two primates, namely the capuchin monkey (Cebus albifrons) and the sub-specie Cebus aequatorialis, endemic to the central coast of Ecuador (Tirira 2011). This location encompasses eight private natural reserves whose buffer zones overlap with the territory of three local communities.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Socio-economic activities in the area

The local communities engage in fishing (sardines, mackerel, sawfish, pampanos, cara, snapper, seabass and grunt); harvesting of mollusks and crustaceans including black shell (Anadara tuberculosa and Anadara similis), red crab (Ucides occidentalis) and blue crab (Cardisoma crassum); tourism due to the beautiful landscape and beaches; agricultural activities including rice, onions and coconut production; salt extraction; and sand extraction, among others. These activities are realized based on the various ecosystems found in each location, which are outlined for Chone River Estuary, Portoviejo River Estuary and the Bálsamo Mountain Range in Tables 2, 3 and 4, respectively. The ecological impacts of these activities are also briefly addressed in this section, as impacts are inherent to these activities.

Table 2. Resource use of different ecosystems in the Chone River Estuary (FIDES 2017a)

| Resources | Uses of ecosystem |

| Mangrove | Capturing red crabs and shells: The gathering of crustaceans and molluscs has been an ancestral activity in the estuary of the Chone river; however, these products are becoming increasingly scarce, due to either loss of habitat (more than 80% of the mangroves has been felled by the shrimp industry), pollution generated throughout the basin, or the shrimp farms.

Tourism: One of the important activities in this territory is ecotourism, which is especially developed on the Corazón and Fragatas Islands. Kayaking, birdwatching and gastronomy are some of the services managed by communities. |

| Estuary | Artisan fishing: The estuary is made up of different fish species that are part of the food staples of the population.

Gathering of molluscs: Likewise, molluscs and crustaceans are collected, the main ones being guariche, concha prieta (black ark) and scallops. Due to the loss of these species’ habitat, as with the impact of pollution, they are no longer commercialized in great volume, but now are used mostly for local consumption. Shrimp: One of the important activities in the area is the production of shrimp for export. The shrimp industry is responsible for having felled more than 80% of mangrove forests in the area, displacing families. The industry is now one of the main causes of pollution in the estuary, especially when pools with pollutants are emptied, modifying the pH of the water. |

| Agriculture | Agricultural activities are performed on a small scale in the area. In winter, the main crops are: corn, cotton and crops of short durations. |

| Wetland La Segúa | Chameras: These are pools of chame (native fish species) production. Chameras involve recovering the area’s emblematic chame species, since exotic species, like tilapia, a predator of chame, have been introduced in the wetland.

Tourism: La Segua wetland has a particular scenic beauty and is also a resting place for migrant birds. Tourism is potentially a very profitable activity in the area and will permit educating visitors about the importance of the wetland. |

| Township of Portovelo | In the town of Portovelo, employment-generating activities have been developed, such as: the cabin restaurant, run by a group of young people with the objective of rescuing gastronomy with mangrove products. In the community workshop La Casita, the association has a venture to manufacture products with mangrove motifs. |

Table 3. Resource use of different ecosystems in the Portoviejo River Estuary (FIDES 2017a)

| Resources | Uses of ecosystem |

| Mangrove | Tourism: Exists within the mangroves’ (San Jacinto) trails, which is a touristic service, sensitizing tourists to the importance of this ecosystem.

Crustacean harvesting: Mangroves are a place where certain species evolve, such as guariche, blue crab and shells that have been the base alimentation of the communities. It is noted that due to the pollution levels in the estuary, the scarcity of these species is increasing. |

| Estuary | Artisanal fishery: The estuary provides many fish for food. Income generated by boat trips.

Tourism: Fluvial itineraries. Shrimp farming industry: Many shrimp farms have been installed, drastically reducing the mangrove forest in the estuary and affecting the environment and the species living there. |

| Beach | Tourism: The area is one of the most important destinations for local tourism. Tourists arrive mainly from Portoviejo, Rocafuerte, Chone, and Tosagua. Peak seasons provide an important income for the communities’ population, especially San Jacinto and Las Gilces, both mainly for gastronomy.

Sand extraction: There are areas where significant volumes of sand are extracted for construction use. This is becoming a problem, as the physiognomy of the beaches changes and the landscape’s beauty is being lost. |

| Agricultural valleys | Rice-growing areas: Another activity that is being developed in the area is agriculture. One of the major crops is rice, especially for the communities of Las Gilces, San Roque, and, to a lesser extent, San Jacinto.

Onion-production areas: The industrial agriculture in certain areas around the communities have developed monoculture, especially of onion, with a high use of agricultural chemicals and labor force from the area (Santa Teresa, San Roque). Coconut-production areas: Las Gilces is an important producer of coconut. Coconut water is one of the most commercialized beverages in the sector. |

| Salt ponds | Production of natural salt: In the estuarine communities, there are salt ponds. In some of them, such as Las Gilces, San Jacinto and San Clemente, the production of natural salt is an important aspect for families, although the price is very low. Salt production has basically three uses and markets: for the processing of fresh cheese, cattle food and fertilizer, mainly for coconut.

Use of plastic (salt): In the salt evaporation ponds (salt pans), sheets of plastic are still used to collect water, which after being dried by the sun, produce the salt. These plastic sheets become a contaminating element once the useful life of the plastic is over, due to improper disposal. Native plants and birds: The beaches, salt pans and the mangrove forest form part of the ecosystem and have important interactions generated between them. There are places of bird nesting, resting and feeding; tourist attractions are therefore a source of employment for the families of the communities. Spirulina: In some salt-producing ponds, spirulina has been found, which is a type of seaweed used for therapeutic purposes (especially for weight loss). However, even though it is beneficial for other activities, it represents a danger because it affects the saltwater, which is the basis for the salt production. |

Table 4. Resource use of different ecosystems in the Bálsamo Mountain Range (FIDES 2017a)

| Resources | Uses of ecosystem |

| Dry-dry Forest | Tourism: Although the tourist activity is relatively new, the Bálsamo Mountain Range is becoming a tourist spot of national interest. There are several dry forest trails along the sea and camping sites in the dry forest.

Research and conservation: In some of the private reserves of the dry forest, wildlife monitoring with camera traps takes place. This information is used to create awareness through educational campaigns among the communities, and to promote scientific tourism. Agriculture: Extension of agricultural frontier, through seasonal crops. Urban development planning in forest areas. Indiscriminate hunting. |

| Marine area | Tourism: The combination of dry forest ecosystem with the beach area is a great attraction for tourists.

Fishing: Fishermen from nearby communities often fish around the area. Irresponsible mining: In some areas, significant volumes of sand are extracted for construction use. This is becoming a problem, as the physiognomy of the beaches changes and the landscape’s beauty is being lost. |

Challenges

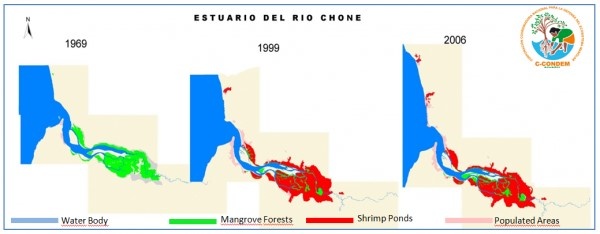

Despite the environmental, social, economic and cultural importance of the mangroves, as well as the existence of a legal framework for protection, more than 80% of the mangroves in the Chone River Estuary and Portoviejo River Estuary in Manabí Province have been destroyed by the shrimp industry. This destruction has deteriorated living conditions for families that have lived off such ecosystem services for generations, mainly due to the decline and loss of species that have been part of the local community’s food security. According to the data of the Center for Integrated Survey of Natural Resources by Remote Sensing (CLIRSEN), there were once 4,171.2 hectares of mangrove forest in the Chone River Estuary in 1969. In 1999, only 704.9 hectares remained, representing a loss of more than 80% of the mangrove forest, which was replaced by the construction of shrimp farms. By 2006, there was a slight mangrove recovery, achieved through efforts by the mangrove communities, as shown in Figure 3. The Chone River Estuary also suffers from pollution caused by the chemical residues of agricultural activities, chemicals from the shrimp industry (Barreto et al. 2011), and the discharge of wastewater.

Figure 3. Destruction of mangrove forests in the Chone River Estuary (C-CONDEM 2007).

The mangrove ecosystem of the Portoviejo River Estuary is also heavily affected by pollution, which is generated by wastewater discharges, poorly treated water coming from oxidation ponds and lagoons and domestic water discharges, as well as waste from agrochemicals that are washed away by rainwater and/or irrigation systems, in addition to organic wastes from livestock activities and by shrimp farming in captivity. Deforestation of mangroves is another existing problem due to the installation and expansion of shrimp farming industries, agricultural plots, and urbanization in the Portoviejo River Estuary.

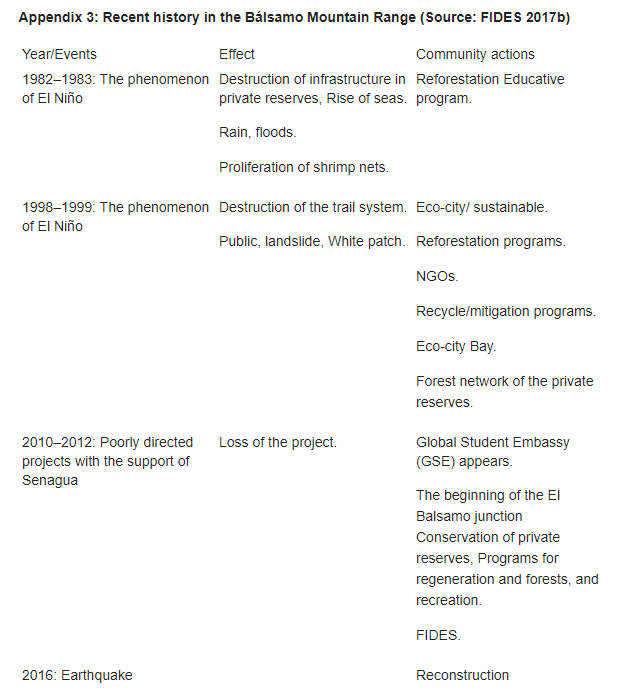

As a result of an information survey in the area, it was determined that the territory of the Bálsamo Mountain Range is threatened by deforestation; extension of the agricultural frontier; urban development (especially of touristic centers); extraction of fine woods; loss of habitat for the fauna species of the zone; and illegal hunting.

Activities

Apart from the mangrove ecosystem and its socio-ecological benefits, emphasis is placed on preserving the connectivity between these two mangrove forests and the dry forest ecosystems. With this objective, work is being done to seek recognition at some level of official protection for the area, either through the state or communal protection. The aim is to strengthen community production activities that alleviate the pressure on natural resources and contribute to the conservation of biodiversity and the ecosystems, as well as the food sovereignty of the communities, the utilization of traditional knowledge and practices, and the incorporation of innovative and sustainable production technologies.

To improve the landscape resilience and management of the Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) in a collective manner, the communities applied the Indicators of Resilience in SEPLS (UNU-IAS, Biodiversity International, IGES & UNDP 2014) to assess the resilience of their landscapes and seascapes. Members of four communities, three private area owners and five public servants of the Ministry of Environment were involved( see Fig. 4). The Foundation for Social Research and Development (FIDES), a local NGO, facilitated this participatory application of the Resilience Indicators. The following areas were evaluated:

- Environmental resilience: Protect, restore and improve the ecosystems and river basins;

- Economic resilience: Diversify local economic activities and implement measures to reduce poverty and guarantee food sovereignty;

- Social resilience: Improve the capacities of local organizations, their empowerment, as well as the participation of social actors;

- Political-institutional resilience: Contribute to the functioning of various institutional and governance mechanisms.

Figure 4. Group discussion in the Resilience Indicators Workshop. Participants in the Portoviejo River Estuary. ©FIDES

Local communities have been implementing restoration processes in certain areas through red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) reforestation, and recovery of mangrove species such as shells (Anadara similis and Anadara tuberculosa) and mouthless crab (Cardisoma crassum) with 4,000 seedlings planted in an area of two hectares. In the state-owned protected area, 8,000 seedlings of mangrove species were planted with the support of park rangers and members of the communities.

The reforestation of dry forest in the Bálsamo Mountain Range is linked to the protection of the white-headed capuchin monkey (Cebus aequatorialis) (Fig. 5), which is listed as Critically Endangered A2cd (CR) under IUCN guidelines (Cornejo & de la Torre 2015).

Figure 5. Sightings of the capuchin monkey by the camera traps in the La Gorda and Punta Verde private reserves (November 16/2016). ©Ramón Cedeño

Community tourism plays a societal and environmental role, since it supports income generation for families and, in this way, relieves pressure on the mangrove ecosystem and dry forest. The tourism infrastructure is improving, including restaurants, cabins and pathways within the mangroves. Youth organizations such as the Group of Youth United for the Development of the Las Gilces Community and the Young Entrepreneurs of the Mangrove of San Jacinto (Portoviejo River Estuary) play an important role in these activities (Fig. 6). In the Bálsamo Mountains, an initiative was proposed to create a touristic route based on the ancestral route of the culture “Los Caras”, with the aim of generating associativity between the private reserves along the landscape.

Figure 6. Youth from UDC building the ecological path. ©UDC Las Gilces

A pilot project for the production of chame (Dormitator latifrons) in rice fields started towards the end of 2017 and is being tested as a sustainable productive activity. The production of crab as an alternative to chame in the rice fields will also be explored (see Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Captivity breeding of chame fish. ©UDC Las Gilces

Artisanal salt extraction from salt ponds, which are part of the landscape, is an ancestral activity that generates income for more than 30 families in the area. A new initiative is being pursued in the Commune Las Gilces in collaboration with the Salt Producers Association to produce and trade gourmet salt and salt for use in cosmetics (see Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Artisanal production of salt in Las Gilces ©FIDES

Training on leadership for youths in the communities, as well as environmental education for school children, collectively prepare the younger generation to sustain the conservation efforts being embarked upon at present.

Results

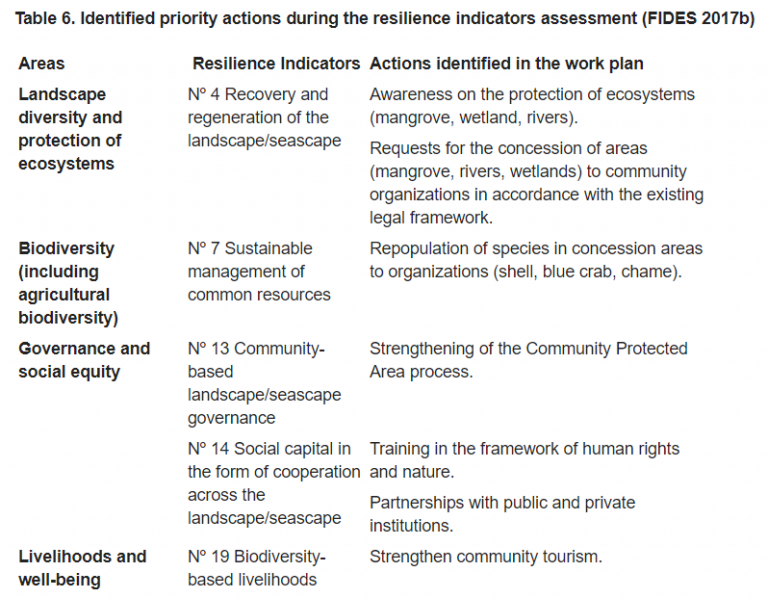

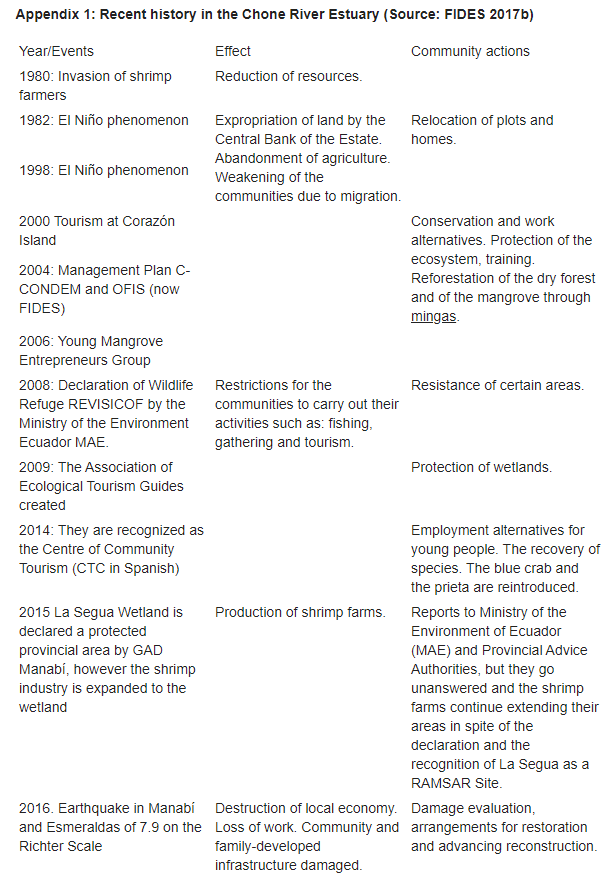

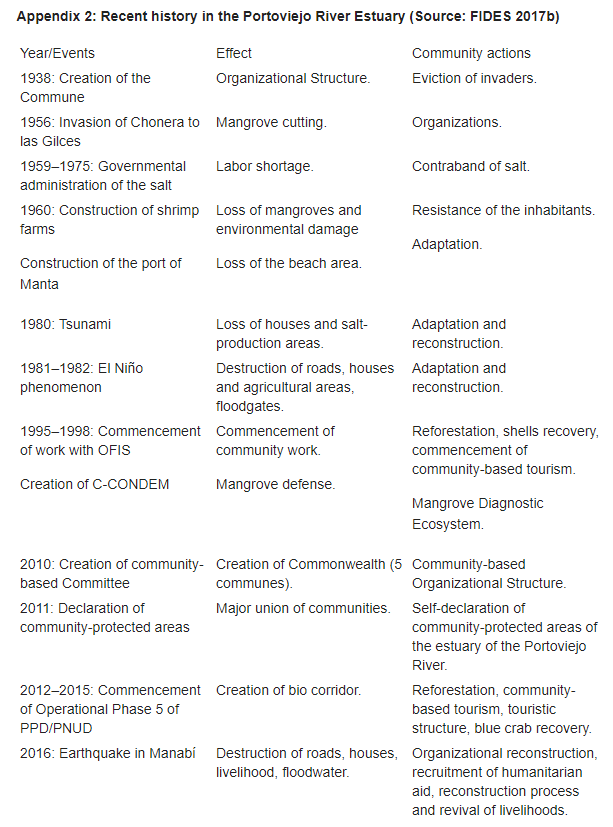

As a result of the resilience assessment workshops, the local communities and organizations outlined the important events in recent history to their livelihoods and ecosystems (Appendices 1, 2 and 3). Likewise, they shared their knowledge on the strengths and weaknesses in the SEPLS, adjusted their existing plans, and developed priority action plans to strengthen the resilience of the SEPLS following the communities’ interests and needs (Table 6).

For example, through the resilience assessment, local community members found that there is great diversity surrounding the canal, rivers, wetlands, mountains, beaches and mangroves in their SEPLS. Uses of these ecosystems include artisan fishing, capturing of conch, red and blue crabs, tourism and agriculture, among others. The communities found that resource management needs to be improved, including training and strengthening of collaboration among existing committees.

Prior to the resilience indicator assessment, community members took some time to revisit the history, social and political situations, and natural resources in the area. This allowed for intergenerational exchanges as well.

Different approaches were taken to protect the ecosystem and people’s livelihoods for each of the three distinct landscapes. The Chone River Estuary is located within a government-protected area and managed according to its official status. The four communities along the Portoviejo River Estuary self-declared their territory as a protected area with communal management and are looking for official recognition. The Bálsamo Mountain Range belongs to a private conservation initiative, and currently there is a debate on the possibility of including the area in the National System of Protected Areas (SNAP).

To secure the remnant mangroves and recover the lost functions, mangrove areas in the Chone River Estuary were gazetted as a protected area in 2004, and those in Portoviejo became a community protected area in 2011. Since then, a series of restoration efforts have been undertaken, including mangrove replanting and integrated river basin management.

As part of the strengthening process for the protection of the communitarian reserve, an intercommunity committee, composed of the four communes of the Portoviejo River, is leading a process to obtain recognition of their protected area by the Ministry of Environment within SNAP.

Currently, the communities of the Portoviejo River Estuary are additionally self-recognized as Territories Preserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (TICCA), which further strengthens their social and political identity, and opens the way for more participative governance.

Several tourism infrastructures were completed in San Jacinto, including the construction of 42 dining cabins on the coastal edge that had been destroyed by an earthquake. Tourism ventures managed by youth groups of San Jacinto and Las Gilces have made significant progress.

In the Portoviejo River Estuary, the Group of Youth United for the Development of the Las Gilces Community (UDC of Las Gilces) is completing an ecological path, which it is calling the “José Alberto Ecological Trail”. This route into the interior of the mangrove forest allows bird watching and includes information provision from native guides. Through this ecological path, environmental education on the importance of the ecosystem will be carried out. The Young Entrepreneurs of the Mangrove of San Jacinto acquired a vessel for sightseeing tours through the estuary, bird watching and informative talks for tourists.

There has been a thorough assessment of potential actions to improve and implement the production and commercialization of gourmet salt with the Salt Producers’ Association (ASPROSAL). To this end, the Environmental Plan for the “Las Pampas” salt mines was revised. This involved an initial assessment regarding compliance with the activities and action plans established in the Management Plan of the “Las Pampas” salt mines, for which the implementation period was from July 2014 to June 2017. The construction of machinery for salt processing, including a dryer and mixer, is also taking place. With the aim of establishing a production chain for this machinery, a consultancy to develop a business plan was hired.

Within the private reserves, the implementation of the tourist route “Los Caras” has had some setbacks, as private reserve owners still focus priority on their individual reserves’ touristic plan and still need to bring attention to collaborative initiatives.

Despite the fact that the Corazón and Fragatas Islands Wildlife Refuge (REVISICOF) has its governmental management plan, park rangers are open to collaborate with reforestation activities and a few of them are communitarian tourist guides from the communities that surround the governmental area, which results in community guides being more supportive of these initiatives.

Discussion

The resilience indicator assessment helped the communities to better understand the strengths and weaknesses of their SEPLS and identify priority actions for their communities. Besides establishing a baseline to quantify the progress of the resilience conditions, the resilience evaluation with local communities and organizations provided an opportunity to recognize historical, social and political situations in the area; share strengths and weaknesses of their SEPLS among community members and other stakeholders; and develop a priority work plan so that participant organizations can incorporate these actions into their management regimes and implement the associated projects. At the same time, the indicators assessment provided an opportunity for community members and other stakeholders to learn more about SEPLS and the communities’ perceptions of the SEPLS. The indicators assessment also helped to recognize the needs of local communities, encourage them to develop co-management plans together and to strengthen the relationship between project organizers and community members, building trust.

The comprehensive landscape approach undertaken at the mouth of the Chone and Portoviejo rivers, including the dry tropical forest of the Bálsamo Mountain Range, makes conservation of the critical mangrove ecosystem possible. At the same time, it allows for the sustainable use of the mangrove ecosystem as an important source for the livelihoods of local communities. This is possible due to collaboration among a wide range of stakeholders, including community-based organizations (CBOs) such as youth associations, community members, governmental entities, private reserve owners and FIDES. Cooperation between different CBOs in the Portoviejo River Estuary is facilitated through the Intercommunal Committee, which provides support to the execution of the different productive activities. In the case of the Chone River Estuary, the link to the landscape between different CBOs is mainly made through tourism. While tourism associations work together to provide tourism services, other productive activities are coordinated by FIDES through the participation of local community promoters. Private reserve owners coordinate their activities through the Balsamo Network of Private Forest Reserves.

Communal organizations promote sustainable activities devoted to restoration and conservation of the mangrove ecosystems through the reforestation of mangroves and dry forest species, reintroduction of species such as blue crab and black ark, organic agriculture, development of alternative livelihoods including community tourism, and artisanal production of higher value salt products. They also plant fruit trees in order to provide food for the capuchin monkey, a critically endangered species in the area.

Different area-based conservation approaches were taken to protect the ecosystem and people’s livelihoods for each of the three distinct sites. As the Chone River Estuary is located within a government-protected area, it is managed according to its official status; however, public servants were sensitized to collaborate with the activities of mangrove restoration and native species reintroduction promoted by the communities settled around the estuary. For the Portoviejo River Estuary, declared as a communitarian protected area with communal management, the figure of the inter-communitarian committee is of great importance in the process of its official recognition, as it reflects the compromise and organization of the four communities in the management of the area before the Ministry of Environment. As the Bálsamo Mountain Range belongs to a private conservation initiative, it becomes more complex to influence the management plan of the owners.

Strengthening local governance is one of the key factors for the success of conservation in the area, considering the significant roles that youth groups are playing in the creation of ecological paths and the management of protected areas. Their work is focused on the improvement of local management capacities, which are paving the way for their territories to become protected areas that are recognized by SNAP. Also, the recognition of the territory as a TICCA contributes to the improvement of local governance.

The activities in Manabí contribute to the conservation of biodiversity because ecotourism, as a business that brings about livelihood improvement, must be based on an intact ecosystem. The local community realized the potential of ecotourism having understood the value that biodiversity brings to them. The area is primarily used for fisheries, but, through the realization of the potential of ecotourism, contributes to the conservation of biodiversity. This fits the definition of Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures, or OECM, which was defined after the SBSTTA 22 of the CBD as: “a geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and, where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socioeconomic, and other locally relevant values.”

From the findings of this case, the indicators of identifying OECMs in SEPLS include the presence of sustained business activities that are based on the elements of biodiversity and the presence of shared understanding among community members about the value of biodiversity.

Conclusions

With the understanding that their economic livelihoods depend on healthy ecosystems, communal organizations were able to collectively promote sustainable activities devoted to restoration and conservation of the ecosystems, namely mangrove and dry forest species reforestation. The reintroduction of species such as blue crab and black ark, and the planting of fruit trees in order to provide food for the capuchin monkey, as well as innovative sustainable practices, such as the breeding of chame fish along rice fields, were implemented.

Local governance is improving as a consequence of community organization, focused on achieving recognition of their protected areas into SNAP. Development of local capacity, including the younger generation, is key to strengthen local governance.

The comprehensive landscape approach encompassing the mouth of the rivers Chone and Portoviejo and including the dry tropical forest of the Bálsamo Mountain Range makes conservation of the critical mangrove ecosystem possible. This is due to the fact that the area can be adequately managed by available resources, including human capital, and is large enough for revitalizing the affected species in the area.

The resilience evaluation helped the local communities and organizations to 1) share knowledge on strengths and weaknesses of the SEPLS; 2) provide opportunities for the debate and analysis of SEPLS between members of the communities; 3) develop priority action plans to strengthen the resilience of the SEPLS; and 4) rethink and recognize how the project would help to address key threats and weaknesses so it can better address the needs of local communities.

Stakeholders of the three distinct protected areas had different ways of addressing action plans derived from the resilience evaluation. Members of communities were able to incorporate these actions into their management plans in a comprehensive manner. Although the government-protected area has its own management plan, it has been possible to promote specific conservation actions among community members in order to strengthen landscape management and resilience. On the other hand, private reserve owners would be able to incorporate their way of managing SEPLS into their management plans.

References

Barreto, S, Gómez, W, Peña, A, Bernal, J & Rivadeneira, Y 2011, Plan de Desarrollo y Ordenamiento Territorial del cantón Sucre, Ecuador.

Berger, WH, Smetacek, VS & Wefer, G. 1989, ‘Ocean productivity and paleoproductivity: an overview’ in Productivity of the ocean – present and past, eds WH Berger, VS Smetacek & G Wefer, Life Sciences Research Report 44, Dahlem Konferenzen, pp 1–34.

Bunt, JS 1992, ‘How can fragile ecosystems best be conserved?’ in Use and misuse of the seafloor eds KJ Hsü & J Thiede, Dahlem workshop reports: environmental science research report 11, Wiley, Chichester, pp 229–242.

C-CONDEM 2007, Destruction of mangrove forest in the Chone River Estuary map, National Coordinating Corporation for the Defense of Mangrove Ecosystems, Ecuador.

Cornejo, F & de la Torre, S 2015, Cebus aequatorialis, The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015, viewed 06 March 2017, <http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015.RLTS.T4081A81232052.en>.

Improvement of the livelihoods of the communities through the sustainable management of productive landscapes and biodiversity conservation in mangrove (Estuaries Chone and Portoviejo), the dry forest (Cordillera del Balsamo) and rainforest (Commune Playa de Oro), GEF-Satoyama Project, Portoviejo, Ecuador.

FIDES 2017b, Memory of a Training Workshop – Indicators of resilience, Portoviejo, Ecuador.

Kathiresan, K & Bingham BL 2001, ‘Biology of Mangroves and Mangrove Ecosystems’, Advances in Marine Biology, vol. 40, pp. 81-251.

López-Lanus, B & Gastezzi, P 2000, ‘An inventory of the birds of Segua Marsh, Manabí, Ecuador’, Cotinga, vol. 13, pp. 59–64.

Ministry of Environment, Ecuador 2007, Plan de Manejo Participativo Comunitario Refugio de Vida Silvestre Islas Corazón y Fragatas, Portoviejo, Ecuador.

Ong, JE 1982, ‘Mangroves and aquaculture in Malaysia’, Ambio vol. 11, pp. 252–257.

Tirira, DG (ed) 2011, Libro rojo de los mamíferos del Ecuador, 2da Edición. Fundación Mamíferos y Conservación, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, y Ministerio del

Ambiente del Ecuador, Publicación especial sobre los mamíferos del Ecuador 8, Quito, Ecuador.

UNU-IAS, Bioversity International, IGES & UNDP 2014, Toolkit for the Indicators of Resilience in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS), <https://satoyama-initiative.org/old/wp/wpcontent/uploads/2014/11/TOOLKIT-X-WEB.pdf>.

Vaca, G & Piguave, X 2012, Inventario de Flora y Fauna del Estuario del Rio Portoviejo, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Campus Bahía, Ecuador.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants of the various training and capacity building activities and the Indicators of Resilience workshops for their valuable inputs; the Government of Ecuador for legal and policy-related support; and the Global Environment Facility for providing funding.