Enhancing communication and co-learning in socio-ecological landscape management through elicitation of local communities’ visions and values

13.12.2019

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION

ECOAGRASOC, Higher Polytechnic School of Engineering, University of Santiago de Compostela

DATE OF SUBMISSION

13/12/2019

REGION

Europe

COUNTRY

Spain

KEYWORDS

Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes; Participatory approaches; Co-Learning; Value conceptualization; Common Land; Ecosystem Management

AUTHOR(S)

Díaz-Varela, Emilio R.1; Blanco-Arias, César A.2; Rodríguez-Morales, Beatriz 1; Díaz-Varela, Ramón A.2

1 ECOAGRASOC. Higher Polytechnic School of Engineering. University of Santiago de Compostela (27002, Lugo, Spain)

2 Department of Botany. Higher Polytechnic School of Engineering. University of Santiago de Compostela (27002, Lugo, Spain)

Corresponding authors: Emilio R. Diaz-Varela emilio.diaz@usc.es

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Abstract

Serra do Xistral is a medium-range (maximum height: 1,052 m) mountainous area in the North of the Autonomous Community of Galicia (Spain). Its Atlantic oceanic climate, characterized by abundant precipitation, winds, and fogs, facilitated the formation of a landscape characterized by extensive wet heathland and bog habitats. These are considered the most valuable ensemble of bog and wet heathlands for biodiversity conservation in all the Iberian northwest, and include blanket bogs unparalleled in all of southwestern Europe. The area is also a European Natura 2000 network site (i.e. nature conservation instrument defined by European environmental regulations). In addition, an essential component for the formation of this ecosystem was the coevolution of natural features with human activities, e.g. cattle and horse livestock husbandry. The area is characterized by a singular ownership regime, the “Communal Forest Land” (MVMC). Decisions on both management approaches and the benefits obtained from the common land are made at MVMC Community Assemblies. Visions and values of local communities are essential in the decision-making process, and in turn have major influence on the management of natural resources and the configuration of the landscapes. However, in many instances such visions and values differ from institutions at different administrative levels. More in-depth knowledge on the visions, values and narratives of local communities would help to enhance communication in the socio-ecological system and ultimately, in its management.

The EU-financed project “LIFE in Common Land” was developed in Serra do Xistral, involving eleven MVMC. Its aims include the development of management approaches for the protection of priority habitats, including incentives like payment for conservation results. A qualitative approach for obtaining information from local communities was developed. Semi-structured interviews with board members of the MVMC Communities were recorded, gathering information about management systems, community organization, and natural resource uses in the area. In addition, questionnaires specifically designed to assess perceptions of ecosystem services and nature conservation measures were collected. Results allowed for characterization of views on nature and ecosystems of the local communities, whose values in many instances differ from those of environmental conservation institutions. Also, important elements of sense of place and attachment of the community members to their environment were identified, as well as environmental conflicts related to wildlife-livestock interactions. These results could be used to develop new ways of understanding and co-learning, which could form the basis of novel approaches to ecosystem management and conservation.

Keywords: Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes, Participatory approaches, Co-Learning, Value conceptualization, Common Land; Ecosystem Management

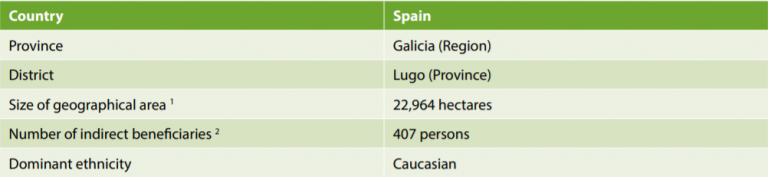

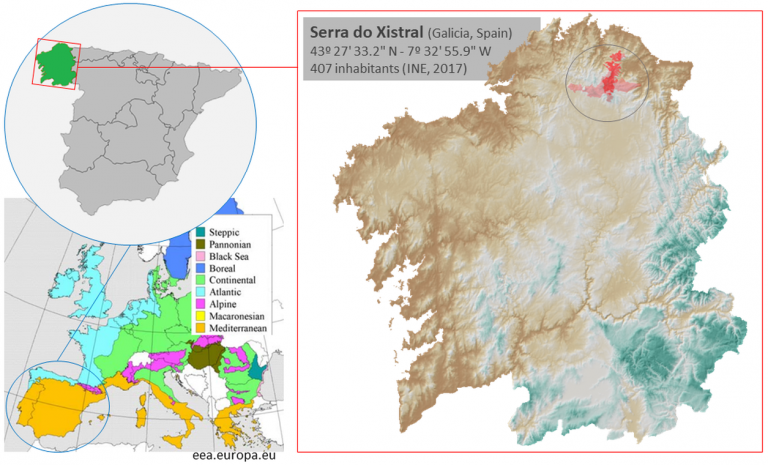

Figure 1. Map of the country and case study region – Galicia, Spain

Figure 2. Land use and land cover map of case study site

1. Introduction

1.1 The role of visions and values in Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes

Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) are the result of the interactions of nature and society in a given geographical and temporal context. Their sustainability through time has depended on the careful management of ecosystem services and the multifunctional use of land within the carrying capacity and resilience of the environment. As a result, they constitute examples of areas with high capacity for biodiversity conservation, socioeconomic development and preservation of cultural assets such as traditional knowledge and local traditions (eds. Bélair et al. 2010; Okayasu & Matsumoto 2013). In many instances, these outcomes have depended to a high degree on the capacity of societies to agree on specific visions and values, which guide the actions collectively undertaken (e.g. what crops and where to produce them, how to repair a wall, etc.) and to set up control elements for individual actions that could go against the collective interest (Ostrom 1990).

The complexity of modern day societies challenges this capacity for vision alignment (Folke et al. 2005; Ostrom 2005). One example is the current understanding of the concept of value. In many cases, and specifically in the field of ecosystem services, the concept tends to be interpreted as monetary value (Gómez-Baggethun et al. 2010). The use of conceptual models for the process of value attribution for ecosystem services, from their recognition as biophysical entities to their trade in the market (e.g. the “ecosystem services cascade”; see e.g. Potschin-Young et al. 2018), is useful to characterize them in the socio-economic subsystem, but has the risk of confounding it with the whole socio-ecological system. A proper understanding of the whole system should include the interactions between society and the environment in all its complexity, including components not exclusively definable by their economic role or value (Constanza et al. 2017). Consequently, and given the plurality of the term, a conceptualization of value is needed (Pascual et al. 2017; Small, Munday & Durance 2017). In this sense, the conceptual framework and approach of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (Díaz et al. 2015; Pascual et al. 2017) represents a system based on series of elements and the interrelations among them, in which different interpretations of “value” should be taken into account and integrated. In general terms, a distinction may be made between non-anthropocentric values and anthropocentric values. Among the former, the intrinsic value of nature can be considered of major relevance, and may include the ‘per se’ value of biodiversity; among the latter both instrumental (i.e. contributions of nature to people) and relational (i.e. components for the good quality of life) can be included (IPBES 2015). An inclusive perspective of values should also take into account their definition at different levels, ranging from the whole society, the community and specific groups, to individuals, and distinguish between more transcendental (i.e. shared collectively in the form of social principles of general application) or contextual (i.e. dependent on a given object or situation) values (Kenter et al. 2015). This will help to understand how values can take the form of principles, preferences, measures or needs (IPBES 2015), and in the latter case, how they are dependent on context (abundance or scarcity of a given resource), barriers (either physical or social obstacles for resource use), or trade-offs between different goods and services for their use (Daw et al. 2011).

Taking all this into account, the analysis of visions, preferences and values and their influence on decisions affecting the environment and natural resources becomes of primary interest to understand the dynamics and sustainability of SEPLS. This would also imply the identification of differences and conflicts between different visions and divergences in the interpretation of values, not only among individuals in a community, but also between different levels and components of the general society.

In the case study presented here, the mountainous area of Serra do Xistral (NW Spain) is analyzed in the framework of a European Union (EU) financed LIFE Program (“LIFE in Common Land”). This project aimed to develop environmental management instruments, including payment for conservation results incentives, in order to improve the conservation state of a series of habitats declared of priority interest in EU environmental regulations. A major area covered by these habitats is in community-managed common lands, so conservation of habitats has a strong relationship with decision-making on the activities and management of these lands by the communities. Considering the strong relationship between incentives and values, the local communities were approached in order to learn in depth about how they manage their resources, their visions on the social-ecological systems they are integrated into, and their perspectives and opinions about the conservation policies developed up to now.

1.2 Study site: Serra do Xistral

Serra do Xistral (Galician language for Xistral Mountains) is a mountainous area in the northern part of the Autonomous Community (region) of Galicia, in Spain (43º 27′ 33.2″ N – 7º 32′ 55.9″ W) (see Fig. 1 and 2). The oceanic climatic influence, which provides the area with abundant precipitation, winds and fogs, combines with medium-range relief (maximum height: 1,052 m ASL). The livestock-centered activities of local communities, dating back to time immemorial, form the characteristic heathland and bog socio-ecological production landscapes (SEPLs).

The Serra do Xistral SEPL supports a diverse ecosystem, rich in plant communities (Romero-Pedreira 2015) and endemic species, and presents three habitats declared of priority interest in the EU Directive for the conservation of natural habitats: active raised bogs (7110*), active blanket bogs (7130*) and Atlantic wet heathlands (4020*). These priority habitats have developed over centuries through their use as pastures (see Fig. 3). Thus, the state of their conservation depends on the management regimes, including the grazing intensity using different livestock species (mainly horse, cow and sheep) and other practices for the regulation of woody biomass for burning and cutting (Fagundez 2016, 2018; Díaz-Varela et al. 2018). While the habitats are recognized to be in a good state of conservation, their continuity over time depends to a large extent on the careful maintenance and improvement of the management regimes, especially those related to pastoralist activities (Muñoz-Barcia et al. 2019).

As commented above, livestock in a semi-wild regime, specifically horses (official sources in the Galician regional government consulted for the project account for a total of 1,324 individuals currently in the study area), cattle and sheep, have played an important role in the use of land from ancient times (Bouhier 2001), and form the backbone of a multifunctional landscape. In present times, a number of ecosystem services are provided by the area, including the production of food (e.g. meat, cheese, honey), energy (windfarms), and ecosystem regulation (biodiversity, pollination, and water purification, to name a few), as well as cultural services (from local knowledge and sense of place to tourism and recreation).

Figure 3. Horses grazing under windmills in the heathlands of Serra do Xistral (Source: Emilio Diaz-Varela)

In Serra do Xistral, pastures are mostly common lands under an ownership regime called “Communal Forest Land” (“Montes Veciñais en Man Común” (MVMC) in Galician language). Lands under the MVMC ownership regime are, by law, indivisible, inalienable, imprescriptible and unseizable. The MVMC are community managed, and all decisions (from management approaches to the destination of benefits) are made democratically through the assembly of the Community of MVMC (CMVMC), with a board acting as representative body. Community decisions thus have a major influence on the management of natural resources in the MVMC, and ultimately, in the configuration of the landscapes. Consequently, the visions and values of local communities are linked to the future of the socio-ecological landscape. Nowadays, different visions of nature and human-nature interactions and the values thereof can be found among the local inhabitants and different institutions and administration levels, especially regarding conservation practices and measures. In many instances, these differences hinder the communication process across the governance system. More in-depth knowledge on the visions, values and narratives of the local communities, and how they perceive themselves in their environment, could lead to a mutual-learning and understanding process which would enhance communication in the socio-ecological system and ultimately, in its management.

2. Description of activities (methods)

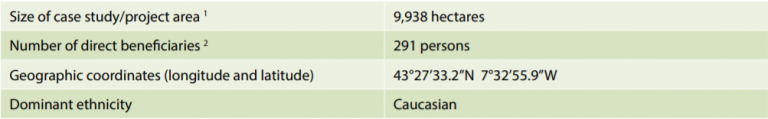

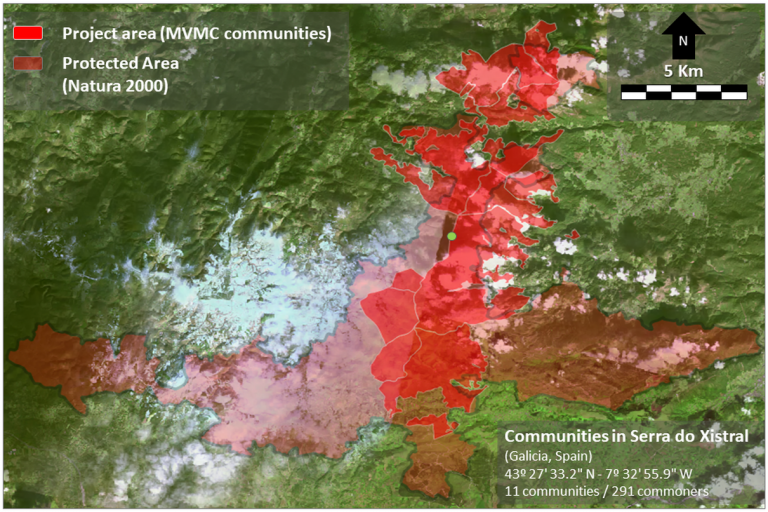

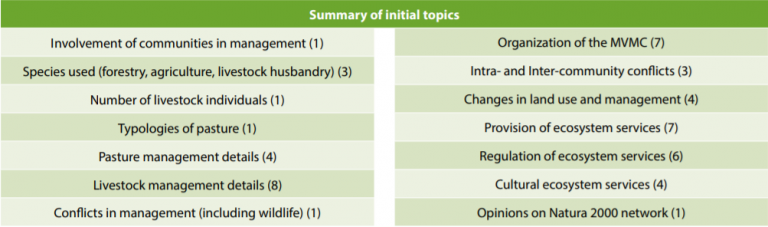

Inside the areas protected under the Natura 2000 network live 407 inhabitants (INE 2017). A total of 11 MVMC communities were addressed in this study, totalling 291 communal forest owners. Information was collected on the communities and their management of the common land with three different goals: a) to check the attitudes of community members towards environmental protection actions, and specifically the EU Natura 2000 program. Discernment of these attitudes will help in understanding the visions and conceptualization of “nature” and associated values; b) to assess the degree of awareness and perception of the ecosystem services provided by the common lands. Such perceptions will be interpreted as an indicator of how people prioritize natural resources and their use, thus informing about the related values; and c) to gather information about the different aspects of management in the common land, both as an organization and a production unit, in order to understand the system and its dynamics. In addition to previous and ongoing studies made by other members of the team (Izco et al. 2006; Ferreiro da Costa et al. 2013; Fagundez 2016, 2018; Díaz-Varela et al. 2018; Muñoz-Barcia et al. 2019), a mixed qualitative-quantitative approach was utilized to retrieve information from the communities. Semi-structured interviews were conducted, addressing the boards of the 11 MVMC communities that participate in the project, considering that they fulfill the conditions of availability and knowledge required by the approach (Gorden 1975; Vallés 2009; Hernández-Carrera 2014). Different subjects were covered including use of the common land, pastureland and livestock management, internal organization of the community and the historical evolution of the use of common land. Next, a questionnaire including 24 questions related to perceptions of and attitudes towards the Natura 2000 program was utilized (covering topics on the utility of the approach, general knowledge about the program, positive and negative views and the level of involvement of the community). Finally, 17 additional questions related to perceptions of ecosystem services were asked (respondents scored provision and regulation services on a 1-5 scale, and were asked to refer to and locate important cultural services-providing areas on a map). In total, 11 meetings were held (one for each community). Interviews and both questionnaires were undertaken in the same meetings (see Fig. 4). The entire process was sound-recorded. The contents of the questionnaire were set up as a reference to define the list of initial topics, for which a summary is shown in Table 1. From the interviews, the identification of induced topics was expected. The initial topics were designed to inform about the specificities of the system, leading to an understanding of its dynamics, and allowing for the identification of relationships between human activities and biodiversity conservation. On the other hand, induced topics would be more concerned with specific values through their relation to the priorities and visions of the communities for resource use.

Figure 4. Two different moments in the development of interviews (Source: C. Blanco-Arias)

Table 1. Summary of initial topics on which information was gathered. Numbers in brackets refer to the number of actual topics covered.

The interviews were directly analyzed from the audio files. This helped to save time and resources, avoiding the transcription of unnecessary sections of the interviews (e.g. explanations made by the interviewers, deviations from the main subject, etc.), and focusing on those aspects initially considered as relevant for the study (Gibbs 2007). Those fragments considered as significant were directly transcribed, coded and registered in a digital database. We assumed the possible loss of context in the fragmented transcription and the possibility of change in what is considered relevant across the study (Gibbs 2007).

In the framework of the “LIFE in Common Land” project, beyond the gathering of information for analysis of the socio-ecological system, the interview protocol was also aimed at the future assessment of changes in the attitudes and values of the local population. To this aim, the interview protocol will be repeated at the end of the project, to check the extent to which the incentives for habitat conservation changed visions, values and priorities in the communities.

3. Results

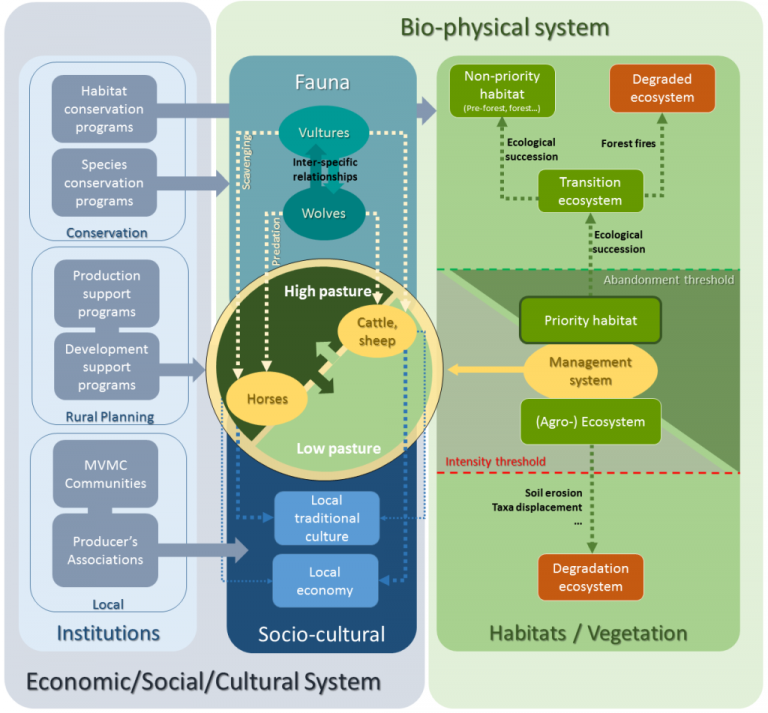

3.1 Systemic interpretation of the SEPL

Information gathered from interviews, together with previous studies (Izco et al. 2006; Ferreiro da Costa et al. 2013; Fagundez 2016, 2018; Díaz-Varela et al. 2018; Muñoz-Barcia et al. 2019), allowed for a general description of the social-ecological system. This characterization is considered as a necessary initial step for the understanding and comprehension of the interactions of stakeholders amongst themselves and with the biophysical environment (see Fig. 5), and thus, with the conservation of priority habitats and ultimately, biodiversity.

Figure 5. Synthetic scheme of the relationships detected between livestock management systems (in the central position), elements of the biophysical system (above and to the right), and elements of the economic, social and cultural system (below and to the left). The scheme includes both different ecosystems of the area and main relevant wildlife species, as well as elements of the economic, social and cultural system, both local and from extra-local administrative units.

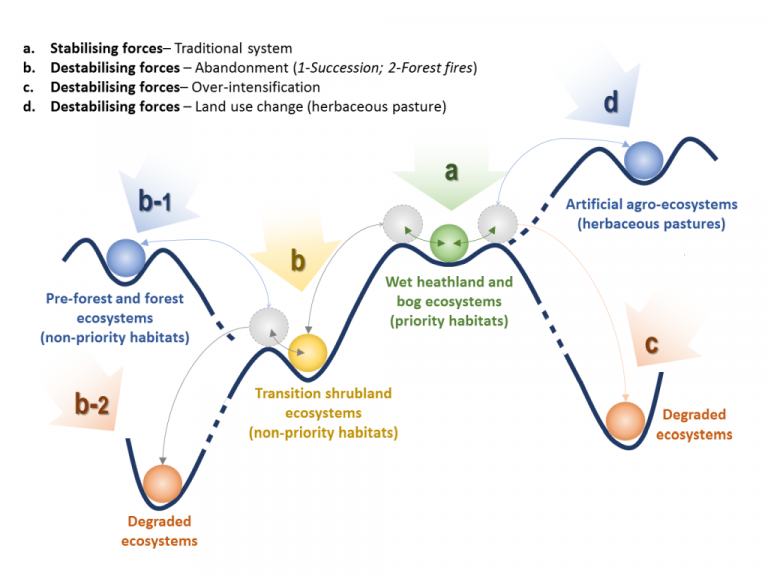

Figure 6 shows conceptually the functioning of the ecosystem and some parameters for its resilience. The management of pastoralism, synergistic with the cycles and characteristic functions of the ecosystem, is the central element that defines the continuity of priority habitats, essential for the conservation and enhancement of biodiversity. This approach is characterized by cyclic management, alternating horse and cattle for the use of pasture, depending on the pasture’s height, species composition and lignification degree. This management acts as the stabilizing force of the system, defining a metastable (i.e. “almost stable”) state. In parallel with this management, subsidies promoted by public administration and institutions favoring territorial governance and alternative economic activities, also support stability. All these factors increase the resilience of the system in the face of external destabilizing forces, which could drive the ecosystems out from their metastable state. In such a case, two possible thresholds were identified, generating two alternative trajectories (see Fig. 7), in both cases leading to a decrease in biodiversity in the ecosystems: the abandonment of livestock activity, leading to high shrub ecosystems, and eventually to pre-forest and forest ecosystems, or to a degraded ecosystem if forest fires take place. The second trajectory would occur in the event of excessive intensity of management (overgrazing, excessive vegetation clearing) beyond a certain threshold, causing the system to evolve towards a degraded ecosystem.

Figure 6. Conceptual model and possible evolution trajectories for the ecosystems in Serra do Xistral. See text for details.

A third trajectory would be driven by the transformation of the heathland ecosystems (priority habitats) to artificial herbaceous pastures or forest plantations. These changes in land use involve important modifications in the management system, and currently their development is limited by regulations for the conservation of natural areas.

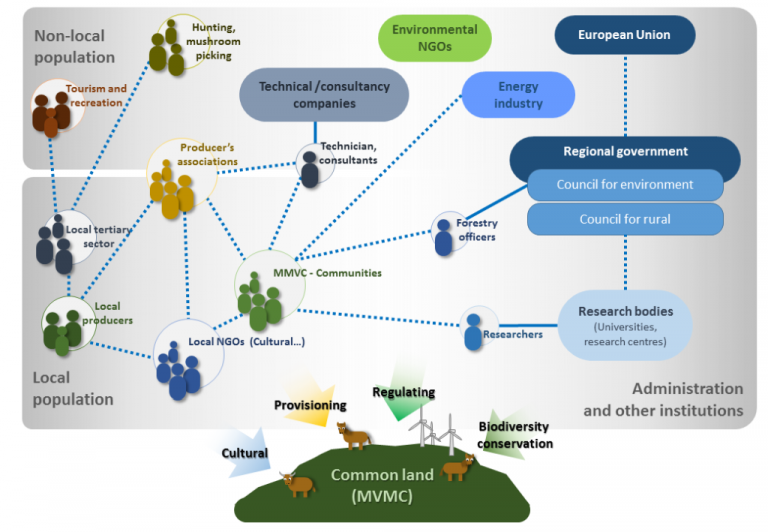

Figure 7. Stakeholder mapping

Finally, the social structure and relationships are represented in a stakeholder map (see Fig. 7), defined from references to actors, institutions and relationships obtained in the interviews. The MVMC communities show a strong link and/or mix with local producers, the local tertiary sector (tourism), and local cultural NGOs. In addition, there are important links with producers associations. Links with non-local individuals include visitors interested in tourism, recreation and other outdoor activities. Indirect connections with institutions include regulations and programs, both in the framework of nature conservation strategies or in rural planning and development. Direct relationships involve public (e.g. forestry officers) or private (e.g. technicians and advisors) intermediaries, with functions including administrative support and extension advisory services. Non-administrative institutions, like non-local environmental NGOs and research institutions, also have interests in the area, and their interaction with the local population is varied – more direct in research projects, and less in conservation activism.

3.2 Specific results for ecosystem services

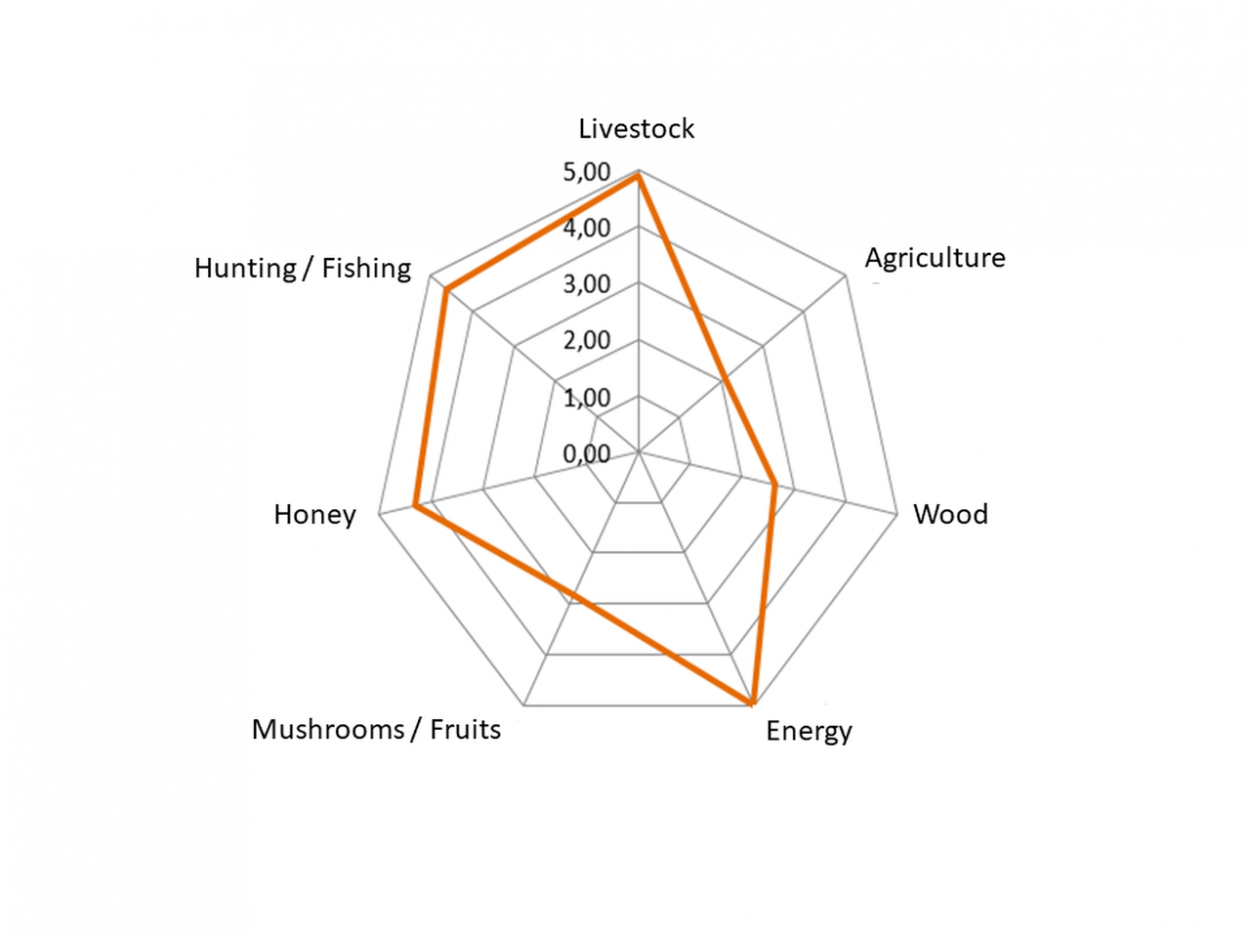

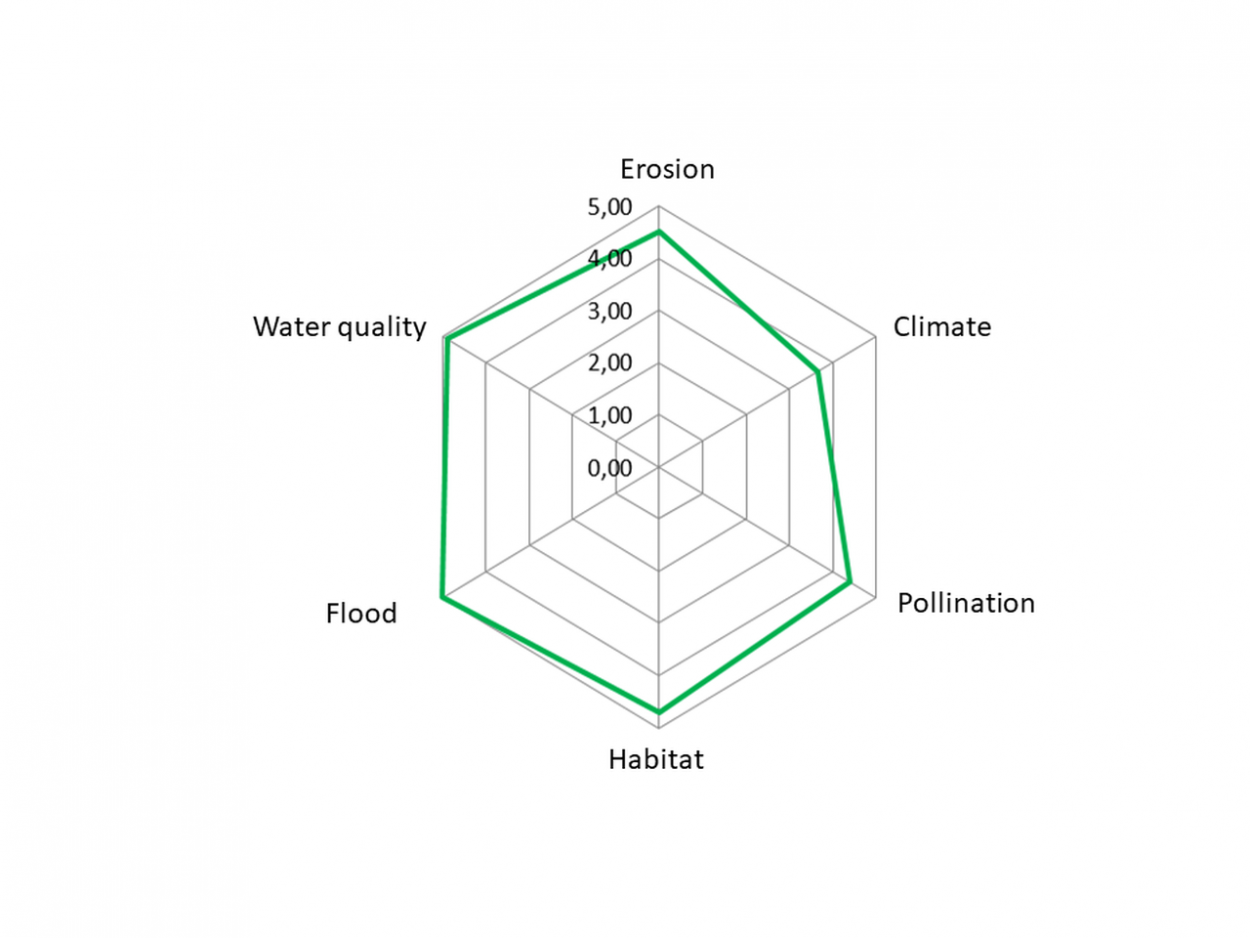

The questions regarding provisioning ecosystem services resulted in ordinal scores from 1-5 regarding the importance of the provision of food from livestock, agriculture, honey production, and mushroom and wild fruit picking; the production of wood; and the production of energy (mainly in windfarms). Energy production got the higher scores, followed by the provision of food through livestock husbandry, followed by hunting/fishing and honey production (see Fig. 8 for more details).

Figure 8. Scores obtained on a 1-5 ordinal scale for provision (left) and regulation (right) ecosystem services

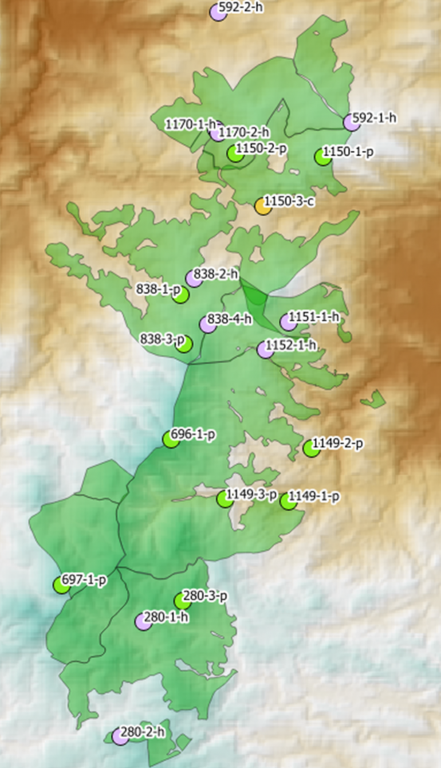

For regulating services, the highest score (see Fig. 8) corresponded to protection against floods, followed by water quality, for which a special awareness has been perceived. The next services in order of importance were habitat, erosion control, and pollination. The least valued service was the climate. Regarding cultural services, the only one measured on the 1-5 ordinal scale was the perception of the possibility of tourist and recreational activities in the area, with relatively high scores (4.27 out of 5). The interviewees also located areas of provision for cultural services, resulting in the identification of 19 spots considered important for their historical value; 20 spots for their outstanding aesthetic landscape; and 9 locations for festivals, fairs or local pilgrimage destinations. Twenty of the former locations were geo-located (See Fig. 9). In general, all local community members declared a high level of personal connection with Serra do Xistral through their way of living. In general terms, the higher importance conferred to provision services, and to those regulation values with clear relationships to production, can be interpreted as a preponderance of instrumental values. Nevertheless, the clear identification and the relationships with the ecosystem of the culturally-valued spots, which can be interpreted as important relational values contributing to the local construction of identity, have to be considered.

Figure 9. Places identified in the interviews related to cultural ecosystem services. Letters in the codes make reference to heritage (h), landscape (p) or celebration (c) related services.

3.3 Specific results on perceptions of nature conservation activities

As commented above, the information gathering approach included questions about the perceptions of the communities concerning conservation initiatives, and specifically, the EU Natura 2000 network.

There was not a consensus among the communities on the utility of the conservation programs for the protection of species, habitats, improvement of water quality or the promotion of sustainable practices. Nevertheless, while all the communities had general knowledge of the conservation program, important deficits were identified related to information exchange between the administrative bodies and the communities. All of the communities reported that the information received from the administration on Natura 2000 was not enough (72% stated a total absence of information), and all of them had insufficient information (36%) or none at all (63%) about subsidies and support measures linked to the protected areas. In addition, all referred to the fact that they were neither asked to be involved in the delineation process, nor informed on how the process developed. Finally, it was generally perceived (82%) that conservation measures linked to the protected areas are prejudicial for agricultural or forestry activities to some degree; nevertheless, almost half of the communities positively view the inclusion of their MVMC in the program.

3.4 Extended information and induced topics

During the interviewing process, a series of frequent themes were identified, which were classified as induced topics. The topics are not mutually exclusive, and in fact have strong mutual relationships. Those identified so far are described below.

Different understanding of “conservation value”. When asked about conservation initiatives, communities normally identified more or less clearly the subject of the conservation (e.g. either by naming a single species or a particular habitat), but in many instances, they did not clearly acknowledge the reason for conservation. This may be due to a confrontation between conservation and production – i.e. they see that conservation threatens the productive activities linked to their way of living. More specifically, some of the statements may suggest that conservation menaces their own rationale of management, and/or that of their ancestors. However, they expressed a clear understanding that their activities contribute to the preservation of the landscape and/or the habitats of interest. Therefore, while there is some agreement on what should be preserved, there are divergences on the vision of why and how.

Lack of communication and neglect by the administration. The lack of communication with administrative bodies was clearly reported in the answers to the initial topics. Communities felt uninformed in different aspects regarding the declaration of protected areas. They also reported several instances of administrative barriers to compensatory measures, like subsidies or payments for wildlife attacks on livestock. Communities therefore reported feeling neglected by the administrative bodies. Frequent comments regarding the absence of policymakers and other public representatives “stepping on the ground” in the area also may be interpreted as a lack of interest or understanding on the part of the administration.

Conflicts with wildlife. In general, conflicts with wildlife were considered an important issue in all the communities, the main ones being wolf (Canis lupus signatus) attacks on livestock (mainly foals and calves). Also, the griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus), while not considered a threat, was pointed out as a worsening factor, as they remove the carcasses making it difficult to prove the attacks and thus to ask for compensatory payments. It is generally acknowledged that wolf attacks have happened from ancient times, but the perception is that they have increased in recent years. Attitudes towards wildlife as a threatening factor reveal possible conflicts between intrinsic values of nature (i.e. conservation of wildlife), and relational values (the continuity of a way of living). The consequences also extend to a conflict with the administration, as it is perceived as a “protector” of the wildlife, instead of the people.

4. Discussion

The current vision of the Natura 2000 network program for nature conservation acknowledges farming as a major contributor to biodiversity. In fact, due to the non-exclusive character of the protected areas regarding human activities, the latter are recognised as an integral part of nature in a mutual partnership process (Olmeda et al. 2014). However, the protection character of the Natura 2000 imposes some specific limitations on productive activities, namely those that can be harmful for the habitats or species of interest that are meant to be protected. This can be a source of conflict with local inhabitants, acknowledged and studied in the search for solutions (Bouwma et al. 2010). In our study, we consider these conflicts as confronting visions of local communities and environmental administrative bodies, whose vision can also be shared by other stakeholders like non-local environmental NGOs, and to a certain extent, some visitors attracted by the natural values of the area.

As shown in our analysis, the structure and dynamics of the system, the preferences of communities regarding provisioning ecosystem services, and the importance given to the obstacles to productive activities set by the administrative nature conservation regulations, characterize the vision of the local communities as centered on productive aspects. Thus, instrumental values are the most apparent. Nevertheless, productive activities should not be considered simply as entrepreneurial activities, but also as an important component of a way of living. The results of the assessment of cultural ecosystem services indicate that an important part of the identification of local inhabitants with their environment is made through their activities in the MVMC, but not only the productive ones. This is evident in the location of a variety of sites recognized as providers of cultural services in Serra do Xistral. Consequently, the consideration of relational values (Chan et al. 2016) as part of the visions of local stakeholders becomes necessary.

While other values and visions could also be acknowledged in the different stakeholders, we identify an important failure in the mutual acknowledgement of two perspectives – one centered in the productive vision, and other in the conservative vision. Consistent with other works in EU states (see e.g. Gallo et al. 2018), this failure emerges through different conflicts: lack of understanding of restrictions, bureaucratic barriers, or communication deficits. The deficiency of a common language, the lack of information channels and the absence of participation of local communities in decision-making are all indicative elements. As a result, the communities have a general perception of the conservative vision as restrictive, viewing the conservation efforts as giving more attention to the preservation of wildlife in the area than to the maintenance of the local inhabitants. This will hinder the acceptance of conservation measures by the communities, which will paradoxically result in a deterioration of the priority habitats, dependent on the traditional perspectives of management.

In addition, it should be considered that the SEPL behaves as a Complex Adaptive System (Preiser et al. 2018). As such, the system itself adapts to changes in ways that are difficult to understand and foresee in many instances. For instance, in the last decades, windmills were installed in the mountains, involving the construction of road infrastructure. Also, in some areas heathlands were transformed into artificial grassland. While the first caused impacts in both landscape and hydrological regimes (Diaz-Varela et al. 2007), it brought new income sources for the MVMC communities, as well as improved access to remote pastures. The second reduced the area of habitats (Gómez-Orellana et al. 2014), but improved the availability and quality of fodder for livestock. Both actions would involve potential harms for the ecosystem, but improve the quality of life for the communities, thus securing their permanence in the area. In addition, changes in management regimes may have consequences for the system’s functioning (e.g. the behavior of wildlife and their interaction with livestock, the outbreak of diseases or invasive species, etc.) that are, together with the influence of global changes, still to be examined.

5. Lessons learned and conclusions

The information obtained through interviews, questionnaires and direct observation of the SEPL provide strong support for the elicitation of the inhabitants’ visions and values, from which a series of lessons can be learned:

- Differing views on the reasons for conservation have been detected between environmental administrations and local communities. For the first, conservation is related to the intrinsic value of habitats and ecosystems – for the latter, as they consider the ecosystems as part of their way of living, instrumental and relational values are behind their visions for conservation.

- Communities reported being ill-informed about the decisions made concerning the conservation areas, from their initial delineation to current management approaches. Also, they feel neglected with regard to the decision-making of administrative bodies. To integrate the participation of communities in conservation schemes, new forms of communication have to be enabled.

- Important changes have affected the socio-ecological system in the last decades, including new road networks and the transformation of heathlands in herbaceous pastures. While these changes may be considered by the local communities as sources of improvement, they will eventually modify the management system. This may bring about new unexpected system behaviors (e.g. new behaviors of wildlife, outbreaks of invasive species, etc.) which are difficult to understand and foresee.

To overcome the conflicts derived from differing visions, restoring common trust and enabling communication strategies are recognized among the necessary measures (Bouwma et al. 2010). Specifically for Serra do Xistral, a conversational approach between the different stakeholders would favor an openness to the variety of visions and values of the SEPL, the incorporation of other perspectives (e.g. those related to rural development or new alternatives of management) and the integration of information about the new dynamics of the system. Such approaches would be a necessary first step for the establishment of an integrative understanding of protected areas, inclusive of local communities’ values, and for the implementation of innovative management schemes. In this specific project, the schemes will be related to payment for results in conservation (i.e. reception of incentives if ecosystem conservation goals are achieved), as well as the development of strategies to add value to conservation-friendly products developed in protected areas. The integration of economic revenue may help to define new dimensions for the instrumental and also relational values associated to the communities’ way of life and, hopefully, to facilitate a common acknowledgement of the intrinsic value of the ecosystems.

Acknowledgements

This work was developed in the framework of the European Commission-financed project LIFE in Common Land – Managing land in common, a sustainable model for conservation and rural development in Special Areas of Conservation (LIFE16 NAT/ES/000707). The authors are very thankful for the suggestions of two reviewers, as well as the contributions made in the SITR 5 authors workshop to improve the quality of the manuscript.

References

Bélair, C, Ichikawa, K, Wong, BYL & Mulongoy, KJ (eds.) 2010, Sustainable use of biological diversity in socio-ecological production landscapes. Background to the ’Satoyama Initiative for the benefit of biodiversity and human wellbeing’, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Technical Series no. 52, Montreal.

Bouhier, A 2001, Galicia. Ensaio xeográfico de análise e interpretación dun vello complexo agrario, Consellería de Agricultura, Gandería e Política Agroalimentaria (Xunta de Galicia), Santiago de Compostela.

Bouwma, IM, van Apeldoorn, R, Çil, A, Snethlage, M, McIntosh, N, Nowicki, N & Braat, LC 2010, Natura 2000 – Addressing conflicts and promoting benefits, Alterra, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

Constanza, R, de Groot, R, Braat, L, Kubiszewski, I, Firoamonti, L, Suton, P, Farber, S & Grasso, M 2017, ‘Twenty years of ecosystem services: How far have we come and how far do we still need to go?’, Ecosystem Services, vol. 28, pp. 1-16.

Chan, KMA, Balvanera, P, Benessaiah, K, Chapman, M, Diaz, S, Gómez-Baggetun, E, Gould, R, Hannahs, N, Jax, K, Klain, S, Luck, GW, Martín-López, B, Muraca, B, Norton, B, Ott, K, Pascual, U, Satterfield, T, Tadaki, M, Taggart, J & Turner, N 2016, ‘Opinion: Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, no. 6, pp. 1462-65.

Daw, T, Brown, K, Rosendo, S & Pomeroy, R 2011, ‘Applying the ecosystem services concept to poverty alleviation: the need to disaggregate human well-being’, Environmental Conservation, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 370–9.

Díaz, S, Demissew, S, Carabias, J, Joly, C, Lonsdale, M, Ash, N…Zlatanova, D 2015, ‘The IPBES Conceptual Framework – connecting nature and people’, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 14, pp. 1-16.

Diaz-Varela, RA, Diaz-Varela, E, Ramil-Rego, P & Calvo-Iglesias, S 2007, ‘Cuantificación efectos ambientales derivados de la fragmentación de hábitats por parques eólicos en áreas de montaña a partir de análisis orientado a objetos de ortofotografías aéreas y análisis del patrón espacial’, Proceedings of the XI International Congress on Project Engineering, AEIPRO, pp. 1202-13.

Diaz-Varela, RA, Calvo-Iglesias, S, Cillero-Castro, C & Díaz-Varela, ER 2018, ‘Sub-metric analisis of vegetation structure in bog-heathland mosaics using very high resolution rpas imagery’, Ecological Indicators, vol. 89, pp. 861-73.

Olmeda, C, Keenleyside, C, Tucker, G & Underwood, E 2014, Farming for Natura 2000. Guidance on how to support Natura 2000 farming systems to achieve conservation objectives, based on Member States good practice experiences, European Commission, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Fagúndez, J 2016, ‘Grazing effects on plant diversity in the endemic Erica mackayana heathland community of north-west Spain’, Plant Ecology & Diversity, vol. 9, pp. 207-17.

Fagúndez, J 2018, ‘Canopy height and competition explain species segregation in wet heathlands’, Journal of Vegetation Science, vol. 2018, pp. 1-10.

Ferreiro da Costa, J, Ramil-Rego, P, Hinojo Sánchez, B, Cillero Castro, C, Rubinos Román, M, Gómez-Orellana, L & Diaz-Varela, RA 2013, ‘Diagnóstico y Caracterización de los Brezales Húmedos (Nat-2000 4020*) de las Sierras Septentrionales de Galicia a partir de Criterios Científicos: Importancia para su Conservación’, Recursos Rurais, vol. 9, pp. 65-77.

Folke, C, Hahn, T, Olsson, P & Norberg, J 2005, ‘Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems’, Annual Review of Environmental Resources, vol. 30, pp. 441-73.

Gallo, M, Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š, Laktić, T, DeMeo, I & Paletto, A 2018, ‘Collaboration and conflicts between stakeholders in drafting the Natura 2000 Management Programme (2015–2020) in Slovenia’, Journal for Nature Conservation, vol. 42, pp. 36-44.

Gibbs, GR 2007, Analyzing Qualitative Data, SAGE Publications, London.

Gómez-Baggethun, E, de Groot, R, Lomas, PL & Montes, C 2010, ‘The history of ecosystem services in economic theory and practice: From early notions to markets and payment schemes’, Ecological Economics, vol. 69, pp. 1209-18.

Gómez-Orellana, L, Hinojo Sánchez, B, Rubinos Román, M, Ramil-Rego, P, Ferreiro da Costa, J & Cillero Castro, C 2014, ‘The peatbogs system of Xistral mountain range as carbon store, valuation, conservation status and threats’, Bol. R. Soc. Esp. Hist. Nat. Sec. Geol., vol. 108, pp. 5-17.

Gorden, R 1975, Interviewing. Strategy, techniques and tactics, Dorsey Press, Homewood, Illinois.

Hernández-Carrera, RM 2014, ‘Qualitative research through interviews: Its analysis by Grounded Theory’, Cuestiones Pedagógicas, no. 23, pp. 187-210.

IPBES 2015, Preliminary guide regarding diverse conceptualization of multiple values of nature and its benefits, including biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services (deliverable 3 (d)). Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), Report 4/INF/13.

Izco, J, Amigo, J, Ramil-Rego, P & Díaz, R 2006, ‘Brezales: biodiversidad, usos y conservación’, Recursos Rurais, no. 2, pp. 1-19.

INE 2017, Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spanish Statistical Office) – Nomenclátor, Nomenclátor: Población del Padrón Continuo por unidad poblacional, viewed 19 June 2019, <http://bit.ly/2WToH7L>.

Kenter, JO, O’Brien, L, Hockley, N, Ravenscroft, N, Fazey, I, Irvine, KN, Reed, MS, Christie, M, Brady, E, Bryce, R, Church, A, Cooper, N, Davies, A, Evely, A, Everard, M, Fish, R, Fisher, JA, Jobstvogt, N, Molloy, C, Orchard-Webb, J, Ranger, S, Ryan, M, Watson, V & Williams, S 2015, ‘What are shared and social values of ecosystems?’, Ecological Economics, vol. 111, pp. 86-99.

Muñoz-Barcia, CV, Lagos, L, Blanco-Arias, CA, Díaz-Varela, RA & Fagúndez, J 2019, ‘Habitat quality assessment of Atlantic wet heathlands in Serra do Xistral, NW Spain’, Geographical Research Letters, no. 45, pp. 1-14.

Okayasu, S & Matsumoto, I 2013, Contributions of the Satoyama Initiative to mainstreaming sustainable use of biodiversity in production landscapes and seascapes, IPSI, UNU-IAS, IGES, Tokyo.

Ostrom, E 2005, Understanding institutional diversity, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Ostrom, E 1990, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Pascual, U, Balvanera, P, Díaz, S, Pataki, G, Roth, E, Stenseke, M …Yagi, N 2017, ‘Valuing nature’s contributions to people: the IPBES approach’, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 26-27, pp. 7-16.

Potschin-Young, M, Haines-Young, R, Görg, C, Heink, U, Jax, K & Schleyer, C 2018, ‘Understanding the role of conceptual frameworks: Reading the ecosystem service cascade’, Ecosystem Services, vol. 29, pp. 428-40.

Preiser, R, Biggs, R, De Vos, A & Folke, C 2018, ‘Social-ecological systems as complex adaptive systems: organizing principles for advancing research methods and approaches’, Ecology and Society, vol. 23, no. 4, p. 46.

Romero-Pedreira, D 2015, ‘Caracterización florística y fitoecoógica de las turberas de las Sierras de Xistral y Ancares (NO de la Península Ibérica)’, Doctoral Thesis, University of A Coruña.

Small, N, Munday, M & Durance, I 2017, ‘The challenge of valuing ecosystem services that have no material benefits’, Global Environmental Change, vol. 44, pp. 57-67.

Vallés, MS 2009, Entrevistas Cualitativas, Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, Madrid.