Engaging Local People in Conserving the Socio-Ecological Production Landscape and Seascape by Practicing Collaborative Governance in Mao’ao Bay, Chinese Taipei (SITR8-10)

20.03.2024

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

Fisheries Research Institute, Council of Agriculture

DATE OF SUBMISSION

19/09/2023

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Chinese Taipei

AUTHOR(S)

Jyun-Long Chen

Kang Hsu

Chun-Pei Liao

Yao-Jen Hsiao

En-Yu Liu

LINK

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Chinese Taipei’s fishing industry has been traditionally based in harbours, and fishing settlements have gradually expanded into their surrounding areas. Accordingly, clusters of fishing communities became typical of Chinese Taipei’s coastal regions. Coastal fishery is a major source of income and livelihoods for local communities along the coast. However, intensified activities (e.g. fisheries aimed at increasing catches, improved fishing efficiency, and development of more efficient fishing gear and fishing methods) (Worm et al. 2009) and climate change have caused a reduction in fishery resources and the destruction of marine ecosystems (Worm et al. 2009; Zhou et al. 2010), especially in coastal areas (Huang and Chuang 2010). Given that marine resources are decreasing, the Fisheries Agency of the Council of Agriculture, the national governing body in charge of Chinese Taipei’s fishery management, began promoting the Coastal Blue Economy Growth (CBEG) programme (Lee 2015) in 2015 to improve the marine ecosystem and enhance fishery resources, adopting a marine stock enhancement approach. Mao’ao Bay was designated as Chinese Taipei’s first sea farming demonstration zone with a community-based sea farming (CBSF) project to begin restoring ecosystems. The project comprised various measures for promoting sustainable fisheries, including pre-planning, stock enhancement, and community-based co-management.

The Mao’ao CBSF project offers important suggestions for building a collaborative governance framework, by involving partners across all levels of government, fishery associations, and residents (community), and for developing communitybased marine resource restoration actions that may be feasible in other contexts (Chen et al. 2020). Useful and beneficial information based on the experiences and framework of promoting the CBSF project has continued to inspire decision makers and natural resources managers.

In recent years, the Forestry Bureau of the Council of Agriculture (FBCA) has been working with the public sector, universities, nonprofit organisations, and local communities to promote the ecological restoration of critical habitats and enhance ecosystem services in low-elevation mountainous ecosystems (e.g. rice terraces and wetlands) based on the concept of the Satoyama Initiative. In 2018, based on the need for maintaining ecosystem services derived from river basins and the integrity of connections among forests, rivers, human settlements, and seas in the natural and rural areas of Chinese Taipei, the FBCA launched a policy programme entitled, “Establishment of a National Ecological Conservation Green Network”. The programme explores integrated approaches to the conservation, revitalisation, and sustainability of socio-ecological landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS). During the initial stage of implementation, expectations for coastal areas within SEPLS have grown, and the Fisheries Research Institute (FRI) has cooperated with the programme since 2019. The FRI started investigating coastal SEPLS, considering how to respond to current trends that centre on resource conservation management and local economic development. FRI researchers began to involve local people alongside government agencies, research institutes and academia, and other stakeholders, in the development of a set of measures for conserving coastal SEPLS.

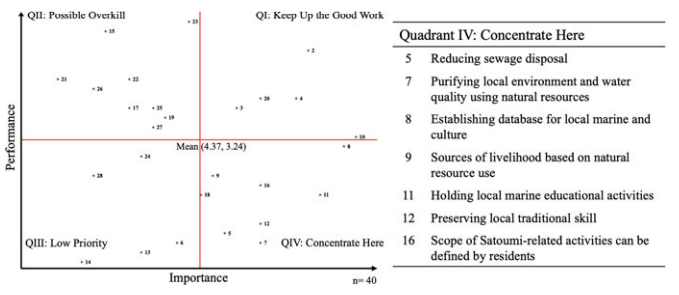

1.2 Socio-Economic and Environmental Characteristics of the Area

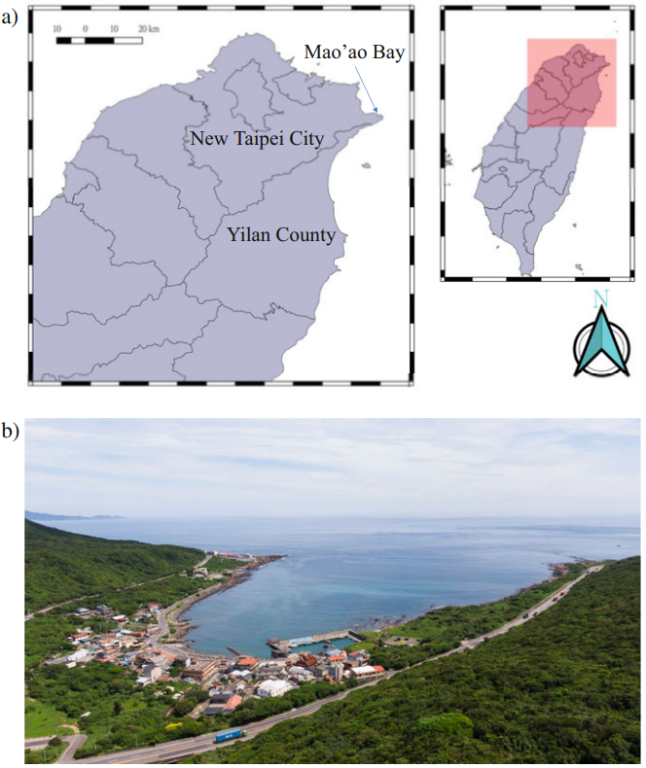

Mao’ao Bay is located in the Gongliao District of New Taipei City, on the northeastern coast of Chinese Taipei. It is home to outstanding fishing grounds that exhibit a rich diversity of marine species due to the three streams that flow into the bay, transporting essential nutrients (Fig. 11.1). Additionally, the shape of the bay provides a great shelter for marine species to live, thereby fostering a stable ecosystem. Notably, small abalones (Haliotis diversicolor) and abalones (Haliotis discus) are cultured there, allowing the community to promote these products as delicacies and specialties. In addition, the local government has begun a basic rehabilitation of economically important fishery resources, including breeding and releasing pharaoh cuttlefish (Sepia pharaonis), small abalones (H. diversicolor), and abalones (H. discus).

Mao’ao is a small fishing village with approximately 200 residents, located close to the Mao’ao fishing harbour (within Mao’ao Bay) (Table 11.1). Fishery is a traditional practice in the Mao’ao Bay. The site exhibits smaller-scale fisheries, such as pole and line fishing, gillnetting, and harvesting. Additionally, the community relies on local produce, such as Gelidium spp., Eucheuma serra, and Grateloupia filicina seaweeds and processed fish roe. Several regulatory mechanisms for resource management exist, including marine protected areas (MPAs), fishing controls (fishing gear restrictions), size restrictions, and closures. Moreover, artificial reefs have been deployed outside the perimeter of Mao’ao Bay, further expanding the favourable conditions for rich marine life.

1.3 Objective and Rationale

It is essential to support both human well-being and the sustainable management of natural resources by understanding the dynamics of complex human–nature interactions within coastal social-ecological systems (Gain et al. 2019). Based on the definition of Satoumi, which is a “coastal sea preserved by humans for their survival with nature and culture” (Yanagi 2013, p. 113), the synergetic coexistence of humans and nature within coastal ecosystems is a central tenet of the Satoumi concept. Regarding the sustainable development goals (SDGs), the FRI emphasises SDG 14 (life below water), SDG 8 (economic growth), SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities), and SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production). Considering these goals, the environmental, social, and economic aspects of coastal communities should be integrated.

The FRI has accumulated experience over the long term via its research on and development of fisheries and has the expertise and human resources for practical consultation. In recent years, FRI researchers have cooperated in the aforementioned policy programmes and been engaged in building partnerships with other organisations. Furthermore, researchers have begun promoting the concept of Satoumi. The FRI’s participation has thus bridged the gap in resource inventory and practical consultation in coastal communities.

In this study, we demonstrate how the FRI has introduced participatory methods for interacting with local communities. To determine a path that leads to ecosystem restoration and furthermore to achieve goals associated with Satoumi, we identified issues in local marine resources use and implemented improvement actions based on a bottom-up approach. Moreover, we established systematic observation of marine resources and their economic use. The promotion of the Satoumi concept relies not only on official funds and policy support but also entails the consideration of local characteristics, the demands of residents, and cooperation and partnerships among stakeholders in the area. Most importantly, enhancing local communities’ capacity via environmental education and strengthening community resilience, as well as protecting local traditional cultures, are pivotal tasks. Thus, the objectives of the project were: (1) to integrate the different voices of multiple stakeholders to achieve harmony within specific social-ecological systems in coastal areas; (2) to empower local communities and other stakeholders to facilitate management in the SEPLS involving coastal villages; and (3) to engage local people in restoring ecosystems in the coastal SEPLS by developing a collaborative governance mechanism.

2 Methodology

The FRI adopted participatory action research (PAR) to establish a public–private collaboration framework for managing Mao’ao Bay’s coastal SEPLS. To date, actions have been comprised of three main activities, which are discussed in the following sections.

This study used PAR to explore how Mao’ao Bay has practiced Satoumi and to establish a governance model for the SEPLS. PAR is a methodology for conducting actions to understand and improve an environment (Bennett 2004). This reflective process is directly linked to action, influenced by an understanding of history, culture, and local context, and is embedded in social relationships. The spirit of PAR allows the people taking part in reflective actions to have much more control over decisions that affect their own lives (Baum and Shipilov 2006).

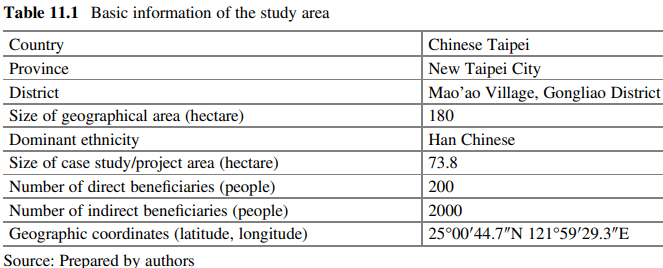

We followed Bennett (2004) to conduct our PAR. First, the research team employed field surveys, secondary data analysis, questionnaire surveys, and in-depth interviews to collect basic information about Mao’ao Bay. We then focused on power relations and tried to blur their boundaries by holding stakeholder and focus group meetings to allow participants to share views and co-create a Satoumi vision and strategy. The second stage focused on building partnerships with local people and empowering them by holding workshops, empowerment courses, and training sessions in environmental monitoring and underwater ecological surveys to facilitate management of the Mao’ao Bay SEPLS. In the final stage, the objective was to form a collaborative governance mechanism by engaging local people to play key roles in citizen science to restore the coastal ecosystem (Fig. 11.2).

2.1 Pre-Planning and Call to Action

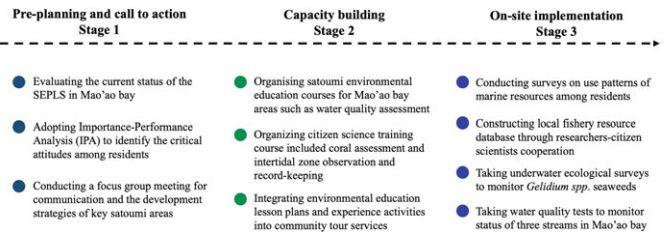

We first implemented a questionnaire survey technique to evaluate the current status of the Mao’ao Bay SEPLS and assess nearby Mao’ao communities. We adopted importance-performance analysis (IPA) (Martilla and James 1977), which allowed us to identify the critical attitudes among residents to analyse the current state of Mao’ao Bay. This method is broadly adopted for the development of marketing strategies and combines respondents’ perceived importance and performance of attributes into a two-dimensional plot to facilitate data interpretation. Attributes are classified into four quadrants to set priorities. Typically, the four quadrants are identified as “keep up the good work” (QI), “possible overkill” (QII), “low priority” (QIII), and “concentrate here” (QIV). The questionnaire design was based on the Japan Satoyama Satoumi Assessment (JSSA) indicators (JSSA 2010) and the Satoumi Manual of Japan (Ministry of the Environment of Japan 2011). From August to September 2020, IPA was conducted to evaluate residents’ attitudes towards the promotion of Satoumi in Mao’ao Bay. Purposive and snowball sampling was employed to convene forty residents to participate in the questionnaire survey. They provided their perceptions on further strategies for the promotion of Satoumi.

We also conducted a focus group meeting to open multiple communication channels and discuss development strategies for Mao’ao Bay. In May 2020, one focus group meeting with 17 participants was held including two local residents, two officials from the fisheries sector in the New Taipei city government, six officials from the Gongliao District Office, one research fellow from the FRI, three researchers from National Taiwan Ocean University, and three representatives of a non-governmental organisation (NGO). The group was convened to explore the following overarching questions: “What are the strengths of and approaches to implementing Satoumi in Mao’ao Bay?” “How might these different approaches be applied to Mao’ao Bay?” and “What lessons can be learned from previous effort to take action to implement the Satoumi approach?” The meeting provided an opportunity to guide the discussion to ascertain the needs and current situation of Mao’ao Bay and the community and to determine strategies for Satoumi development.

2.2 Capacity Building

At the capacity-building stage, we considered the empowerment of local communities and other stakeholders to facilitate management in Mao’ao Bay. Additionally, our purpose was to raise awareness among locals of marine environmental conditions, nurture relevant talent, recruit teams to promote Satoumi education, and build a human resources database.

In September 2020, after identifying and evaluating local social and ecological resources from field surveys, questionnaire surveys, and the focus group meeting, a critical issue was revealed—the community’s concern for the Mao’ao Bay environment—especially for water quality and the resources on which residents relied. Thus, we first planned and organised Satoumi environmental education courses for the Mao’ao Bay area, such as on water quality assessment. This course educated local people on how to sample water from the three streams within Mao’ao Bay and how to test and record the data in cooperation with National Taiwan Ocean University. A total of 20 residents finished the course.

The other course was a citizen science training course designed to enable the locals to conduct intertidal/underwater ecological surveys and to encourage them to take action. The course included coral assessment and intertidal zone observation and record-keeping in cooperation with an NGO called the Taiwan Association for Marine Environment and Education and the local elementary school. The training course educated residents and local elementary students on monitoring the marine environment via adoption of scientific methods. A total of 29 participants finished the course.

2.3 On-Site Practical Implementation: Coastal Ecosystem Conservation

Citizen science has emerged as a way to generate large datasets and environmental awareness among target groups (Eitzel et al. 2017). Community-based monitoring (CBM) is a crucial element of many citizen science initiatives (Conrad and Hilchey 2011). CBM involves local stakeholders in monitoring local interests or concerns, ensuring citizens are involved as scientists, not just data collectors (Fulton et al. 2019). Thus, on-site practical implementation of the project included citizen science for the investigation of important native species such as Gelidium spp. seaweeds and other species. Actions taken at this stage were to engage local people in restoring coastal ecosystems in the SEPLS by developing a co-management mechanism.

In order to fully comprehend marine resource utiliation and its current status in Mao’ao Bay, FRI researchers cooperated with residents to collect logbook data on catch per unit of effort (CPUE), income per unit of effort (IPUE), harvested geographic location, and local perceptions of and attitudes towards marine resource use patterns assessed during the major coastal fishing season (April to October 2021). A total of 366 data points were collected from five residents with experience in harvesting ranging from 3 to 62 years. The collection of logbook data was performed to help us not only to observe how residents depend on the local fishery resources, but also to establish a record of harvested species and the socio-economic contribution of the resources. We also conducted workshops in the summer of 2021 with the Amas (people who harvest coastal marine resources by free diving) to identify relevant species from oral interviews and carry out underwater Satoumi actions (such as the citizen science capacity building for diving and water quality monitoring by residents). These actions enabled us to better grasp information on the daily lives of residents and the harvest to apply to the development path of the Satoumi.

Finally, to verify the interactive effects of seaweed production with different environmental factors or human disturbances, we cooperated with eco-scientist divers and residents to co-establish ecosystem data for Mao’ao Bay. For the early planning and implementation, this science-based action began with a focus on algal flora, which has both ecosystem and socio-economic value.

3 Results

3.1 Observations

3.1.1 Mapping Residents’ Attitudes

Through IPA To establish the Satoumi strategies, we mainly focused on Quadrant IV, “Concentrate Here”, as the points in this area have high priority for improvement and opportunity, as perceived by residents (Fig. 11.3). There were seven items within Quadrant IV that required attention: residents assisting in reducing sewage disposal; use of natural resources to purify the local environment and water quality; establishment of database of local marine resources and culture; residents can earn living from natural resources; holding local marine educational activities; preservation of local traditional skill; and locals can define the scope of Satoumi-related activities (Fig. 11.3). Among these items, two main critical issues were identified. First, residents cared about sewage disposal but felt dissatisfied with the current situation. Second, residents thought highly about educational activities, the database for marine resources and culture, the benefits that locals could earn from nature, and the preservation of traditional skills. However, they were again found to be dissatisfied with the current situation of these issues. These attitudes and critical issues identified through IPA suggested a potential direction for Mao’ao Bay to implement Satoumi actions.

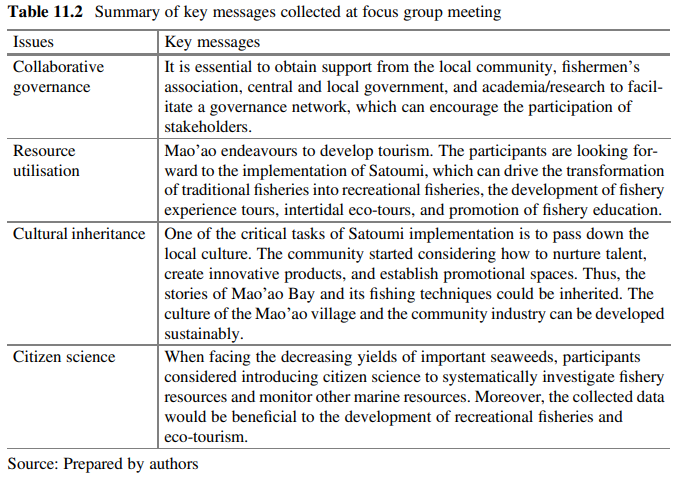

3.1.2 Developing Strategies

Through a Focus Group Meeting The focus group meeting in 2020 successfully created a space for stakeholders to discuss the future development of Mao’ao Bay. The four main issues identified were: “Collaborative Governance”, “Resource Utilisation”, “Cultural Inheritance”, and “Citizen Science” (Table 11.2). These issues were then turned into actions to implement the Satoumi approach in Mao’ao. Furthermore, the meeting contributed to the establishment of the “Mao’ao Satoumi Platform”. In 2021, the Platform played a critical role in allowing local people and other participants to brainstorm Satoumi actions for Mao’ao Bay. The platform held two meetings with a total of 64 participants in 2021. A consensus was reached among most participants on the importance of underwater ecological surveys and environmental monitoring.

3.2 Capacity Building

3.2.1 Enhancing Locals’ Awareness of Resource Utilisation

During the water quality assessment courses, residents learned the technique to conduct water quality tests using API water test kits.1 This helped them to understand anthropogenic impacts on their environment. For example, one of the streams in the Mao’ao Bay that was tested showed a higher value of NH3-N that might be caused by residential sewage. Moreover, some of the participants mentioned that increasing sewage, discharged by restaurants, may also be affecting water quality in Mao’ao Bay (Fig. 11.4).

The citizen science training courses taught residents and local elementary students to monitor the marine environment by adopting scientific methods. The content of the course was designed according to the actual environment of Mao’ao Bay, for example, the characteristics of its marine ecosystem (e.g. coral reefs, sandy shores, intertidal zones, marine species and their characteristics, symbiotic relationships, food chain, and relevant research). Moreover, safety instructions and survey techniques on intertidal observation and underwater ecological monitoring were provided. After the training courses, two residents both with over 50 years of experience in free diving in Mao’ao Bay engaged in co-establishing ecosystem data for Mao’ao Bay (Fig. 11.5).

1 Including test kits for testing Ammonia (NH3/NH4), Nitrate (NO3 -), Nitrite (NO2 -), Phosphate (PO4 -), and Carbonate Hardness (KH).

3.2.2 Transforming Experiences into Knowledge Facilitation

In order to fulfil the expectations of participants on developing tourism, the community integrated the Satoumi environmental education lesson plan2 and experience activities (e.g. intertidal observation) into community tour services. For example, at present, the Mao’ao community offers environmental interpretation services and sampling of local traditional cuisine for visitors. Development of tourism activities offered a beneficial opportunity for the Mao’ao community to develop a model comprising both environmental education and industrial development. Furthermore, in our experiences in Mao’ao communities, we observed that local awareness and organisational capacity were increasing. The locals are now able to observe marinerelated issues autonomously and have begun to interact with research institutes. The ongoing work in Mao’ao Bay and the experiences we have obtained constitute a practical methodology for the expansion of Satoumi in Chinese Taipei.

3.3 Coastal Ecosystem Conservation Actions

3.3.1 Local Marine Resource Utilisation Survey

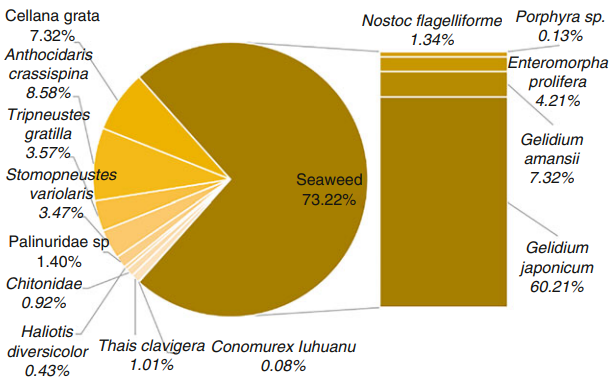

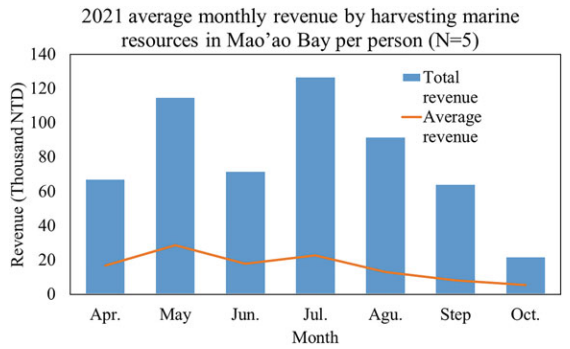

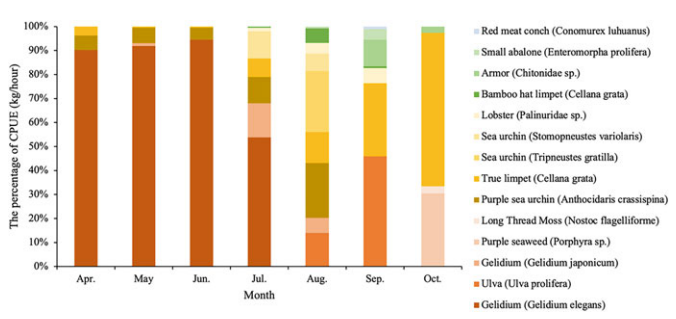

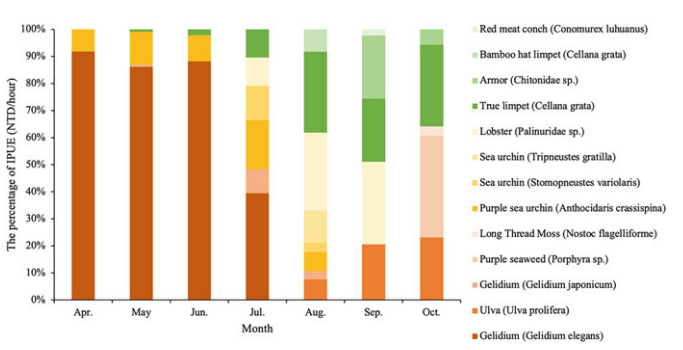

Use patterns of marine resources in Mao’ao Bay obtained from logbook data showed a total of 2303.4 kg of catch (wet weight) in the coastal area of Mao’ao Bay by dive fishing or harvesting from April to October 2021. Of this, seaweed accounted for 70%, while the other 30% was high-value sea urchins and sea snails (Figs. 11.6 and 11.7). The harvest brought a total income of approximately 560,000 NTD3 to five residents. The average monthly income per individual from April to September ranged from 5460 NTD to 28,760 NTD (approximately USD182–959) (Fig. 11.8). Regarding monthly average revenue, July was the highest (23% of total revenue), and October (4%) was the lowest, which indicates summer is the most important harvest season. This highlights the importance of artisanal harvesting and fisheries in Mao’ao for livelihood support. Likewise, as residents also utilise the catch for their own consumption, it also is a critical source of nutrition for self-sufficiency.

The average monthly effort per resident ranged from 9.68 to 87.39 h, with the lowest monthly effort in April (15.8 h/month). In June, the average collection effort decreased to 17.67 h/month due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Amid the pandemic, residents greatly reduced the number of times they went out to harvest to maintain social distance from other people. Numbers rebounded to an average of 57.87 h per resident in August, 48.62 h in September, and 44.45 h in October.

The logbook data on harvests indicate that Gelidium is an economically important species in spring and summer. In the earlier harvest season, Gelidium amansii is the major harvested species due to its better gelatinisation, while Gelidium japonicum, commonly known as “dabinzai”, is primarily harvested after August. This data shows the irreplaceability of Gelidium for supporting the livelihood and culture of the residents of Mao’ao Bay during all harvest seasons (Fig. 11.9).

The highest contributing species to the economy of the community by year were seaweeds, such as Gelidium and Ulva, followed by a sea urchin, mainly purple sea urchin (Anthocidaris crassispina) in the early season, which is replaced by Tripneustes gratilla and Stomopneustes variolaris after June. Lobsters have the highest catch value per unit effort, however, during a limited period (Fig. 11.10). A stable IPUE shown for Cellana grata, which is collected both for selfconsumption and for giving to friends and relatives, demonstrates the cultural and social value of self-sufficiency, sharing, and giving in this fishing village culture.

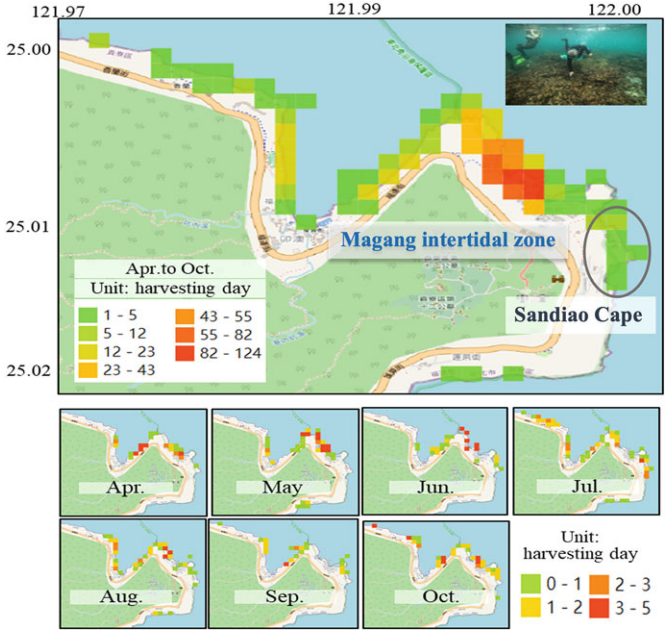

In terms of the geographical distribution of harvesting (Fig. 11.11), Mao’ao Bay is the geographic harvest centre. Harvesting extends to the coasts on the east and west sides of the bay from April to October. The northeast side of Mao’ao Bay (Magang intertidal zone) exhibits a higher frequency of harvesting throughout the year due to its wider hinterland. Concerning seasonal changes, the frequency of fishing in April, July, and August is concentrated on the inner side of Mao’ao Bay. The area from Sandiao Cape to the Magang intertidal zone has a high frequency of fishing throughout the year.

Regarding sales channels, most residents in the sample sold products by themselves before the COVID-19 pandemic, while some were making stable sales to restaurants. Concerning attitudes towards resource utilisation, residents gave high scores on satisfaction with each harvest trip, and their harvesting experiences were not correlated with the IPUE.

The main motivation for the sampled residents to engage in harvesting, other than tidal factors, was based on the weather and sea conditions and related to their own physical condition. Specifically, collecting the coastal fishery resources not only provides economic support to residents, but is also part of their life. That is to say, the ecosystem services provided by the Mao’ao Bay are irreplaceable to the residents that harvest them.

Our study found that community households expressed an open attitude towards marine resource utilisation, believing that the ocean is public property and that everyone has the right to share its resources when the level of use is reasonable. However, they did express a desire to maintain the environment between the shore and the bay as tourist numbers increase. Local residents expressed their desire to demand respect for the local environment from visitors, such as by preventing them from leaving debris behind in the village and on the coast, and assuring tourists comply with regulations, such as parking their cars in the designated area.

3.3.2 New Actions: From Users to Citizen Scientists

From logbook data, we can identify information on important species for local residents. To construct a more systematic ecological survey, we expanded the findings through workshops held in 2021 for further discussion with residents. During the workshops, residents reported that Eucheuma, a type of seaweed that plays a very important economic and cultural roles in Mao’ao Bay, had become very scarce over the previous 2 years. Particularly in 2021, most residents reported that its production was very low, and only a few traces were found in the middle reef of Mao’ao Bay. Thus, due to insufficient production, residents were unable to sell Eucheuma during the spring and summer of 2021, with only a small amount collected by the Amas for their own consumption.

The residents believed that one of the reasons for the decreasing amount of Eucheuma was a change in the composition of nutrients and other substances in Mao’ao Bay caused by an increase in tourism and more sewage from restaurants. Accordingly, the residents applied what they learned in the environmental education courses to conduct water quality monitoring autonomously. Another factor noted by the residents that could explain the rapid decrease in Eucheuma production is the absence of typhoons (Hung et al. 2013), which could cause other algae to occupy the original habitat of Eucheuma. Through these activities, we observed that residents had not only gained the skills to monitor water quality and observe coral conditions, but also had a deeper understanding of the environmental impact of their own behaviour. This increased capacity and awareness of the residents shown in their activities illustrate how local people conducting scientific data collection can serve as a capacity-building exercise in future local promotion of citizen science (Freiwald et al. 2018).

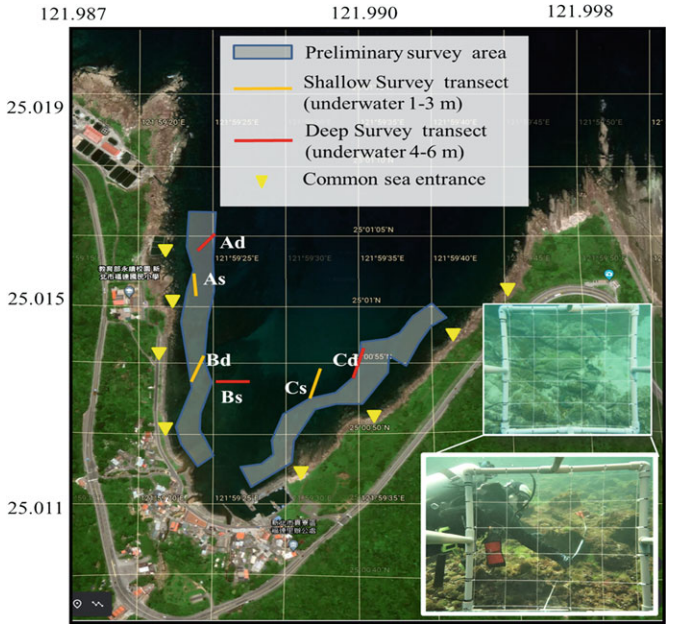

3.3.3 Co-Creating Panel Data of Ecosystems

To figure out the disappearing Eucheuma phenomena, the last piece of the puzzle to be put in place was verification of the interactive effects of seaweed production with different environmental factors and/or human disturbances. A total of four scientific diving surveys were conducted in the spring (March to May) and summer (June to August) of 2021, at six sample sites (Fig. 11.12). The major purpose was to identify the dominant algae species and their seasonal changes in Mao’ao Bay.

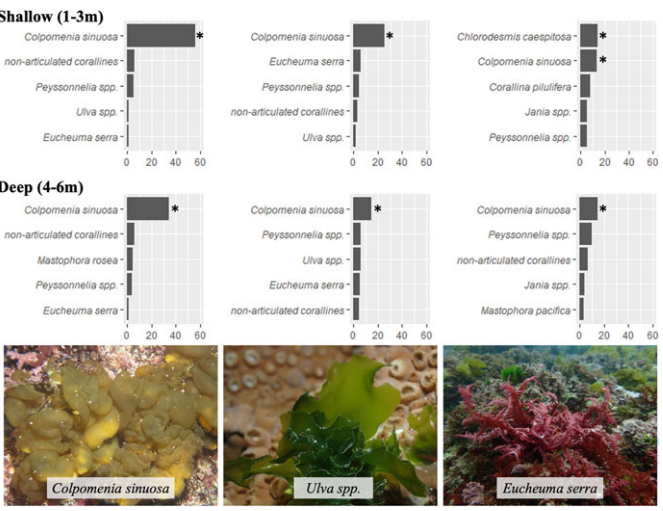

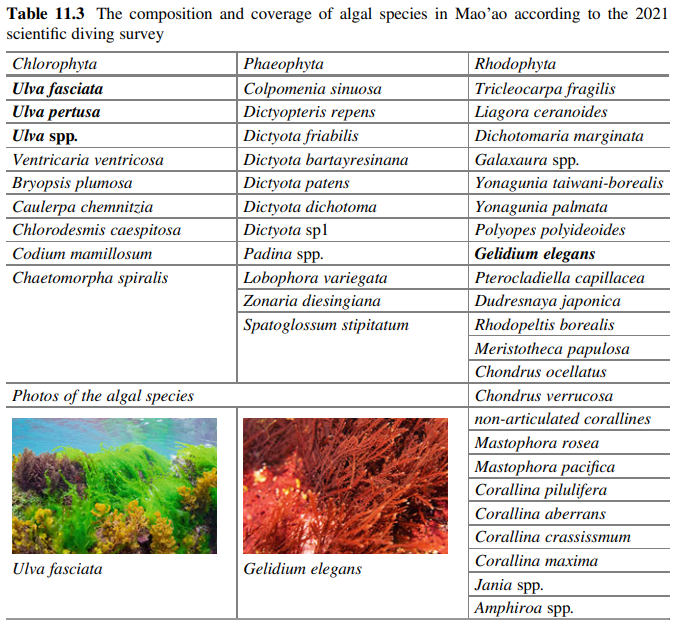

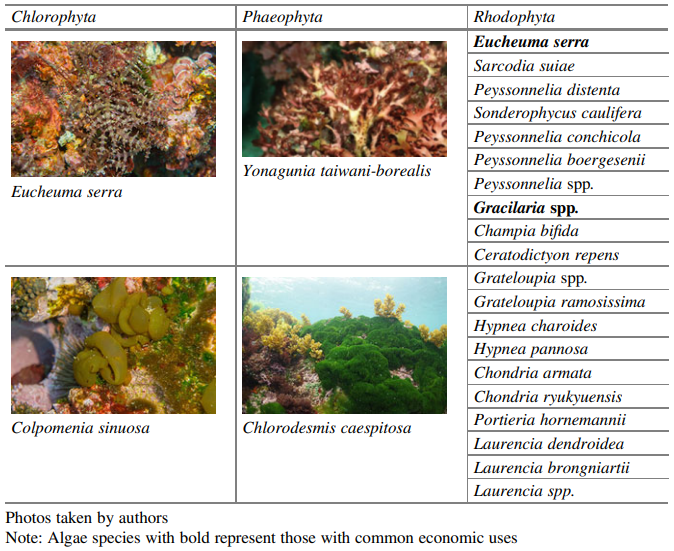

A total of 63 species of algae were recorded in Mao’ao Bay during the year 2021 (Appendix, Table 11.3), including 9 species of Chlorophyta, 11 species of Phaeophyta, and 43 species of Rhodophyta. In May, 29 species were recorded at As and 24 species at Ad, 36 species at Bs and 35 species at Bd, and 33 species at Cs, and 32 species at Cd. In August, the numbers were 23 species at As and 17 species at As, 22 species at Bs and 20 species at Bd, and 32 species at Cs and 21 species at Cd.

The number of species was higher in spring (May) than in summer (August). The algae coverage of Mao’ao Bay averaged 57.5% in May and 28.0% in August. The results indicate that location was the most important factor affecting the distribution of Eucheuma, followed by the depth and season (Fig. 11.13).

Areas with a high coverage rate of Eucheuma may be related to microhabitats. The areas with strong wave energy and more aerated water may meet the microhabitat conditions for the growth of Eucheuma. There could also be other factors, such as fewer predators (e.g. sea urchins or algal-feeding fishes), less fishing, or simply being located in the tail of a stream, where fragmentation of Eucheuma is suitable for reproduction.

We found no significant difference in depth among all sample stations regarding the natural distribution of Eucheuma, implying that the effects of fishing pressure, water temperature, and wave conditions at both shallow and deep sample site gradients were not significant this year. However, the two depths of 1–3 and 4–6 m may not significantly affect the natural distribution of Eucheuma. This means that if there are drastic changes in harvesting activities, water temperatures, and wave conditions, there is still an opportunity to compare these two depth differences at the same location. Therefore, future underwater surveys of Eucheuma should incorporate factors such as harvesting activity, water temperatures, and wave conditions. These results were to contribute to the experimental design of scientific diving surveys the following year in plans to centralise survey resources and make the survey more efficient. In addition, although there was no significant difference between the two depths for Eucheuma, other species such as the green algae Chlorella Taiwan, showed different distributions affected by microhabitat conditions. This suggests further research on environmental elements of the important microhabitat is required.

A seasonal effect on the natural distribution of Eucheuma was not significantly different among the sample stations, indicating that the coverage rate of Eucheuma did not decrease after the collection season (mid-March to the end of August) for the survey year. Eucheuma is perennial, so this year’s coverage may affect the growth of the following years. However, seasons significantly affect the coverage of algae species and cause dominant species to change. Whether there is competition or growth of other algae must be further observed. Accordingly, further resource monitoring of Eucheuma needs to examine a single species while considering the status of other algae. In the future, we suggest that water temperature, water quality, harvesting activity, and competition should be included as factors in such monitoring.

4 Lessons Learned

To promote Satoumi in Chinese Taipei, the FRI aimed to identify a mutually beneficial relationship between humans and nature that not only focuses on environmental resources, but also encourages sustainable economic development and social networks in coastal areas. Thus far, the partnership has involved the public and private sectors and NGOs, and over 200 individuals have participated directly or indirectly in the process. Our study, therefore, yielded the following outcomes:

- Having ascertained diverse attitudes and opinions among local stakeholders through the questionnaire survey and the focus group meeting, we suggested techniques to encourage interactions among stakeholders, facilitate consensus, and intensify partnerships between local and relevant organisations. In summary, the applied techniques proved useful for developing strategies for the advancement of Satoumi.

- The introduction of Satoumi environmental education and citizen science training courses to residents in the communities increased their awareness of the condition of their marine environment. Furthermore, the content of these community empowerment courses was based on local awareness and the results of local resource inventories. This increased the willingness of community members to participate. The Satoumi concept and actions introduced in Mao’ao Bay were found to be effective for SEPLS management. Although the water quality and underwater monitoring are still a work in progress, these actions encouraged the residents to take autonomous precautionary measures. This may be helpful for further preventing and halting destruction of coastal ecosystems and achieving restoration objectives in the future.

- Providing practical methods for acquiring knowledge on marine resources and fishery management encouraged community members to continuously promote Satoumi actions. Additionally, the Satoumi education lesson plans offered an opportunity for the Mao’ao community to promote its fishing culture, local ecological knowledge, and related ecosystem services.

- The involvement of multiple stakeholders in community-based resource restoration in Mao’ao Bay formed the actor network for collaborative governance. Such multi-stakeholder collaboration establishes multiple communication channels that facilitate the exchange of techniques and information for the purpose of resource management and economic development. Moreover, we found that this governance network for the SEPLS in Mao’ao Bay enhanced stakeholders’ sense of identity and their willingness to engage in restoration actions.

- We have established a “Satoumi Information Platform” for broader dissemination of the Satoumi concept and case studies (see https://satoumi.tw) to draw public attention to coastal areas. The platform also serves as a forum to facilitate the cooperation of cross-governmental bodies to promote Satoumi activities in more comprehensive and diverse ways. The ongoing task is to recruit local people with multi-disciplinary talent into our “Satoumi Extension Task Force” to enrich human resources and to seek more potential and creative ways to engage in transdisciplinary cooperation for restoration actions.

5 Conclusions

This study demonstrated the practice of the concept of Satoumi in Chinese Taipei’s coastal fishing community, aiming to improve the well-being of coastal people and the resilience of a coastal SEPLS. Through surveys on the utilisation of local fishery resources and species, as well as consultations with residents on development, we sought strategies to improve the well-being of Mao’ao Bay. We attempted to enhance productivity and biodiversity through human manipulation and interaction between humans and nature, specifically by enrolling the residents in training courses. Therefore, coastal people were found to play a key role in restoring coastal ecosystems, not only as users and observers, but also as recorders and conservation practitioners. The relationships between the various fishery resources used by coastal people and their marine habitats can be further enhanced by empowering local people. This could help local people to understand how dynamic systems for implementing restoration measures can be developed, and to consider restoration methods and effectiveness in a holistic manner in response to natural conditions and human activities. Therefore, we realised the importance of improving our understanding on the connection between important species and their habitats through scientific surveys with the participation of the residents themselves.

Local people are now partly involved in Satoumi actions. This local involvement has played a vital part in the long-term coastal ecosystem monitoring and restoration in Mao’ao Bay. We believe that local people, scientists, and other stakeholders could cooperate to govern their coastal ecosystems and their communities in the short term. Finally, based on our practical experience, we suggest that the participatory methods we employed could be inspiring to other cases within a specific context, especially in coastal areas.

Acknowledgements Sincere gratitude and thanks are expressed to residents, participants, researchers, and other stakeholder groups of the Mao’ao community for providing valuable assistance for the study. Certain contents in this study have been submitted to the IPSI Secretariat as an IPSI case study. The work was funded by the “Establishment of a National Ecological Conservation Green Network” policy programme of the Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Chinese Taipei).

Appendix

References

Baum JA, Shipilov AV (2006) Ecological approaches to organizations. In: Clegg SR, Hardy C, Lawrence T, Nord WR (eds) The SAGE handbook of organization studies. Sage, London

Bennett M (2004) A review of the literature on the benefits and drawbacks of participatory action research. First Peoples Child Fam Rev 1(1):19–32

Chen JL, Hsu K, Chuang CT (2020) How do fishery resources enhance the development of coastal fishing communities: lessons learned from a community-based sea farming project in Taiwan. Ocean Coast Manag 184:105015

Conrad CC, Hilchey KG (2011) A review of citizen science and community-based environmental monitoring: issues and opportunities. Environ Monit Assess 176(1):273–291

Eitzel MV, Cappadonna JL, Santos-Lang C, Duerr RE, Virapongse A, West SE et al (2017) Citizen science terminology matters: exploring key terms. Citiz Sci Theory Pract 2(1):1. https://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.96

Freiwald J, Meyer R, Caselle JE, Blanchette CA, Hovel K, Neilson D, Dugan J, Altstatt J, Nielsen K, Bursek J (2018) Citizen science monitoring of marine protected areas: case studies and recommendations for integration into monitoring programs. Mar Ecol 39:e12470. https://doi.org/10.1111/maec.12470

Fulton S, López-Sagástegui C, Weaver AH, Fitzmaurice-Cahluni F, Galindo C, Fernández-Rivera Melo F et al (2019) Untapped potential of citizen science in Mexican small-scale fisheries. Front Mar Sci 6:517

Gain AK, Ashik-Ur-Rahman M, Vafeidis A (2019) Exploring human-nature interaction on the coastal floodplain in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta through the lens of Ostrom’s socialecological systems framework. Environ Res Commun 1(5):051003

Google (2022) Google earth [Mao’ao Bay, New Taipei City, Taiwan]. https://www.google.com/intl/zh-TW/earth/. Accessed 3 Jan 2022

Huang H-W, Chuang C-T (2010) Fishing capacity management in Taiwan: experiences and prospects. Mar Policy 34(1):70–76

Hung CC, Chung CC, Gong GC, Jan S, Tsai Y, Chen KS et al (2013) Nutrient supply in the southern East China Sea after typhoon Morakot. J Mar Res 71(1–2):133–149

Japan Satoyama Satoumi Assessment (JSSA) (2010) Satoyama-Satoumi ecosystems and human well-being: socio-ecological production landscapes of Japan—summary for decision makers. United Nations University, Tokyo

Lee KT (2015) On the promotion of demonstration area of fish farming in the coastal waters of Taiwan. Research Report of Fishery Agency, Council of Agriculture. (in Chinese)

Martilla JA, James JC (1977) Importance-performance analysis. J Mark 41(1):77–79

Ministry of the Environment of Japan (2011) Satoumi manual. https://www.env.go.jp/water/heisa/satoumi/common/satoumi_manual_all.pdf. Accessed 29 June 2022. (in Japanese)

Worm B, Hilborn R, Baum JK, Branch TA, Collie JS, Costello C, Fogarty MJ, Fulton EA, Hutchings JA, Jennings S (2009) Rebuilding global fisheries. Science 325(5940):578–585

Yanagi T (2013) Japanese commons in the coastal seas: how the Satoumi concept harmonizes human activity in coastal seas with high productivity and diversity. Springer, Netherlands

Zhou S, Smith AD, Punt AE, Richardson AJ, Gibbs M, Fulton EA, Pascoe S, Bulman C, Bayliss P, Sainsbury K (2010) Ecosystem-based fisheries management requires a change to the selective fishing philosophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(21):9485–9489

Note

The opinions expressed in this chapter are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNU-IAS, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent.

Open Access This chapter is licenced under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ igo/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to UNU-IAS, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. If you remix, transform, or build upon this book or a part thereof, you must distribute your contributions under the same licence as the original. The use of the UNU-IAS name and logo, shall be subject to a separate written licence agreement between UNU-IAS and the user and is not authorised as part of this CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO licence. Note that the link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the licence.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from

the copyright holder.