Conserving local marine and terrestrial biodiversity and protecting community resources through participatory landscape governance in Semau Island, Indonesia

30.10.2018

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION

UNDP/GEF SGP, Jakarta; Independent Consultant, Berlin; Independent Consultant, Seattle; UNDP, New York

DATE OF SUBMISSION

30/10/2018

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Indonesia

KEYWORDS

Coastal & fisheries management; Reforestation; Traditional knowledge; Participatory landscape governance;

Agrochemical-use reduction

AUTHOR(S)

Dwihastarini, Catharina1; Tamara Tschentscher2; Gregory Mock3; and Diana Salvemini4

1 UNDP/GEF SGP, Jakarta, 12130, Indonesia

2 Independent Consultant, Berlin, 10245, Germany

3 Independent Consultant, Seattle, Washington, USA

4 UNDP, New York, NY-10025, USA

Corresponding authors:

Catharina Dwihastarini

Tamara Tschentscher

Gregory Mock

Diana Salvemini

Abstract

While significant progress has been made in expanding the national networks of Protected Areas in the last few decades, most biodiversity remains outside of formal PA systems in production landscapes involving agriculture, forestry, and other land and water uses. The fate of this biodiversity, and of the vital ecosystem services it sustains, will depend on the sound management of these landscapes and seascapes.

In Semau Island in Indonesia, the community-based landscape approach supported by the COMDEKS Programme aims to preserve island ecosystem functions through sustainable management of forest cover, as well as coastal, marine and coral reef systems, enhance resilience of agriculture and mariculture systems through improved cultivation practices and water conservation methods, promote alternative livelihoods for local communities, and foster participatory decisionmaking on environmental governance at the landscape level. With Semau Island being a rich ecological habitat hosting monsoon forests, and surrounded by one of the world’s richest coral reefs, such community-based initiatives are vital to creating a ”society in harmony with nature” and conserving the rich local marine and terrestrial biodiversity.

Supported initiatives have contributed to improved water management and seaweed farming practices, have promoted organic agriculture, and have empowered local communities to establish new institutions and networks as well as negotiate new agreements to protect community resources and local biodiversity. Environmental forums and other community institutions have been formed by local clan leaders, village governments, and community members to Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 4 51 Chapter 5: Conserving local marine and terrestrial biodiversity and protecting community resources establish and enforce environmental agreements. These agreements cover activities such as watershed protection, seaweed farming and mangrove restoration. In Batuinan Village, for example, community members have declared a 3-ha water catchment area as a conservation zone to raise the local water table.

This case study showcases local community activities in Indonesia that maintain and revitalize critical production landscapes and seascapes, and documents knowledge and best practices from successful on-the-ground activities to build the resilience of socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS) by developing and diversifying livelihoods while enhancing biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services.

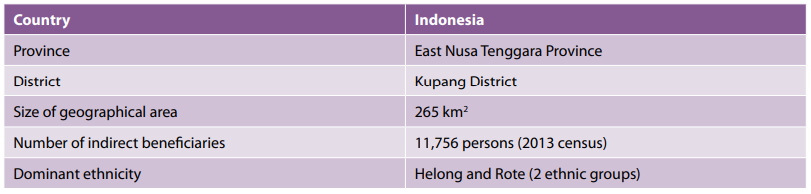

Figure 1. Map of the country and case study region. (Source: East Nusa Tenggara Province and Google Maps.)

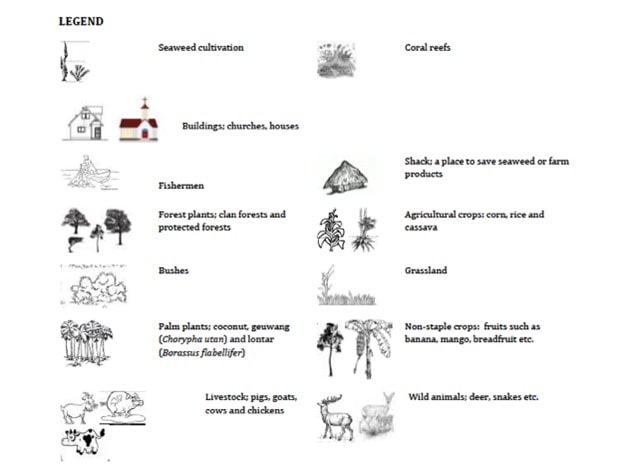

Figure 2. Land use and land cover map of case study site (Source: Bingkai Indonesia Foundation).

1. Introduction

Funded by the Japan Biodiversity Fund, the COMDEKS Programme (2011-2016) is a unique global effort implemented by UNDP in twenty countries, in partnership with the Ministry of the Environment of Japan, the CBD Secretariat, and the United Nations University – Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability. Working through the UNDP-implemented GEF Small Grants Programme, COMDEKS builds the capacities of community organizations to take collective action for adaptive landscape management in pursuit of social and ecological resilience.

While significant progress has been made in expanding the national networks of Protected Areas in the last few decades, most biodiversity remains outside of formal PA systems in production landscapes involving agriculture, forestry, and other land and water uses. The fate of this biodiversity, and of the vital ecosystem services it sustains, will depend on the sound management of these landscapes and seascapes.

In Semau Island in Indonesia, the COMDEKS-supported community-based landscape approach aims to preserve island ecosystem functions through sustainable management of forest cover, as well as coastal, marine and coral reef systems, enhance resilience of agriculture and mariculture systems through improved cultivation practices and water conservation methods, promote alternative livelihoods for local communities, and foster participatory decision-making on environmental governance at the landscape level. With Semau Island being a rich ecological habitat hosting monsoon forests, and surrounded by one of the world’s richest coral reefs, such community-based initiatives are vital to creating a ”society in harmony with nature” and conserving the rich local marine and terrestrial biodiversity.

This case study showcases local community activities in Indonesia that maintain and revitalize critical production landscapes and seascapes, and documents knowledge and best practices from successful on-the-ground activities to build the resilience of socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS) by developing and diversifying livelihoods while enhancing biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services.

2. The Landscape

2.1 Geography

The target area selected as the focus of the COMDEKS project in Indonesia is Semau Island, which is a 265 km2 island located in the western portion of Kupang District, the capital of East Nusa Tenggara Province. Semau Island borders the Sawu Sea in the south, west and north, and the Semau Strait to the east (see Fig.1). Administratively, the island is part of Kupang District and is divided into two areas: the Semau Sub-District in the north, consisting of eight villages, and the South Semau Sub-District in the south, consisting of six villages.

Semau Island is a lowland island with the average highest points at 50 m above sea level. It consists of coral and limestone, with a thin layer of soil on the surface. Most soil types found in Semau Island are Mediterranean, latosol, and alluvial with alkali saturation and limited clay content, particularly kaolinite, making it nutrient poor (Sutedjo, 2009).

For generations, the communities of these 14 villages have survived on the available agricultural and marine resources of the small island. Located in the Wallace bioregion, the island is host to rich marine, terrestrial, and coastal biodiversity. However, given the limited freshwater supply and thin soil layer, both agriculture and biodiversity are increasingly threatened, and the island faces a disproportionate risk from climate change and extreme weather (see Fig.2) (GEF SGP Indonesia 2014).

2.2 Biological resources and land use

Semau Island is a rich ecological habitat hosting monsoon forests, and the surrounding Sawu Sea is home to one of the world’s richest coral reef covers. The Sawu Sea is also a critical habitat and migration corridor for 18 sea mammal species, including two endangered species: the blue whale and the sperm whale (YPPL and TNC 2011).

The local monsoon forest consists of tree species shedding their leaves during the dry season and growing new foliage during the rainy season. Some of these species are particularly significant to the lives of the Semau people, as they are used to build houses and boats, and are also sources of food and medicines. In addition to threats from climate change, biodiversity on the island and the surrounding sea is threatened by the excessive use of chemicals in agriculture, which decreases soil fertility and results in chemicals in the soil being carried to the oceans through rainwater. The use of chemicals in agriculture rose in the last two decades and has increased ever since the community was introduced to vegetable seedlings and hybrid corn. Because land cultivation with mechanical equipment is difficult on the karst terrain, farmers rely on herbicides and pesticides to assist with land clearing and weed control. After the land is utilized for farming for five to six years, farmers are forced to abandon it with the expectation that the soil fertility will gradually recover. Additionally, deforestation is a serious threat, with trees being cut faster than they can be replenished (GEF SGP Indonesia 2014).

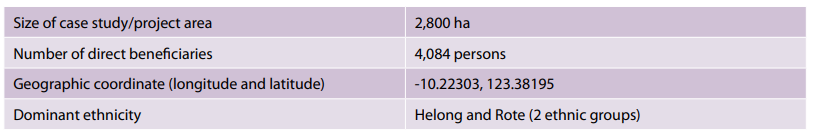

2.3 Socio-economic context

In 2013, the population in Semau Island numbered 11,756, with an average population density of 44 people per square kilometer. The majority of the island’s inhabitants belong to two ethnic groups (clans) with different cultures and languages: the Helong and the Rote. Until a few years ago, clan leaders governed the distribution of land. Today, the Village Government regulates the utilization of the coast and adjacent shallow waters (extending several hundred meters from the coastline). The people of Semau Island largely depend on farming and fishing for their livelihoods. Seaweed farming, which only started in 2001, has become the main source of income for communities living along the coast (see Fig.3 and 4). When freshwater from wells is available, short-term cash crops such as fruits and vegetables provide another source of income besides fishing and seaweed farming. Rice and corn, on the other hand, are the community’s primary source of food, and these locally grown staple crops are largely kept for family consumption. In addition to farming, raising livestock is important to the people of the island. Fishing occurs throughout the year, except for the rainy season when the monsoon brings high waves and strong winds. Development in Semau Island has been slow, as a number of people believe that the Semau people have magical powers, and prior to 2000, government officials were often reluctant to be sent to Semau Island, resulting in a lack of development initiatives in this region (GEF SGP Indonesia 2014).

Figure 3. Shallow waters off Semau Island, SGP/COMDEKS Indonesia

Figure 4. Seaweed farming is one of the major local sources of income, SGP/COMDEKS Indonesia

2.4 Key environmental and social challenges

The principal environmental and social vulnerabilities in the target landscape are related to the availability of water and inappropriate agricultural practices and land use. Particular challenges include the following (GEF SGP Indonesia, 2014):

- Limited supply of fresh water for both agricultural and domestic uses: Rainfall, which is the primary source of water for agriculture, is limited, with an annual precipitation of only 700-1,000 mm. Moreover, there is an insufficient number of wells, which are the primary source of water for drinking and bathing. While the government has constructed dams in several villages, a number of them are malfunctioning or experiencing siltation (BPS, 2009).

- Limited knowledge of agricultural practices and extension services: The District Government has a limited number of agricultural extension staff and rarely conducts any extension services on the island, such as scientific research and dissemination of information on agricultural practices through farmer education. This has resulted in a low level of knowledge on agriculture and sustainable, innovative practices that can increase productivity and income.

- Soil degradation, pollution and loss of biodiversity due to the inappropriate use of chemicals: In order to speed the cultivation of farm fields, the community relies heavily on herbicides and pesticides. Unfortunately, the soil types on the island are naturally nutrient poor, and the excessive use of chemicals further degrades soil quality. The result is that farmers are forced to abandon farmland after 5 to 6 years of use to let the soil recover. In addition, overuse of chemicals harms local biodiversity, both on land and in the surrounding sea when these chemicals are carried to the ocean in rainwater (see Fig. 5).

- Climate change and extreme weather: The biodiversity and human communities of the island are threatened due to a disproportionate risk from climate change and extreme weather events, which have increased in frequency in recent years.

- Lack of knowledge and skills to improve livelihoods: Community groups currently lack the skills and knowledge base to spur local innovation, improve economic activity and increase the local standard of living. Lack of capacity often limits the activity of these groups in the construction of basic village infrastructure.

- Deforestation: Increasing deforestation in the area, particularly from land clearance for agricultural use due to local population growth, has further threatened biodiversity and sustainable land management.

Figure 5. Degraded and abandoned farm land, SGP/COMDEKS

Indonesia

3. COMDEKS activities, achievements, and impacts

3.1 The landscape approach and use of resilience indicators

The set of 20 Indicators of Resilience of socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS), developed by Bioversity International and the United Nations University, is a centerpiece of the community consultation process. The COMDEKS methodology relies on community consultation to drive a process of participatory landscape planning. As part of this process, community members and other stakeholders come together to conduct a baseline assessment of landscape resilience, forge a Landscape Strategy on the basis of this assessment, and identify potential community actions to carry out the Strategy. The resilience indicators figure prominently in all three of these steps. As a focus of discussion, analysis, and negotiation, they are integral to the community process of generating baseline information, reaching consensus on the primary challenges to local resilience, and developing a plan of action to address these challenges. Because of their central role enabling group discussion and interaction, they are also critical to the process of generating the social capital necessary to undertake community-driven landscape projects (UNU-IAS 2013; UNU-IAS et al 2014).

Moreover, the usefulness of the resilience indicators is not restricted to the initial baseline assessment and the early stages of participatory landscape planning. They are also critical at the end of the COMDEKS grant cycle. Aside from their central role in the landscape planning process, they are also a key tool used to capture perceptions of local stakeholders of changes in landscape resilience due to supported initiatives. During the ex-post baseline assessment at the completion of COMDEKS projects, the resilience indicators are again scored, and scores compared with those from the ex-ante baseline assessment. Although comparing indicator scores from the baseline assessment to indicator scores from the ex-post assessment cannot be used as a quantitative measure of landscape resilience change, it can be used to highlight changes in local perceptions due to the completed COMDEKS projects and to determine progress toward the landscape goals enunciated in the Landscape Strategy. Thus, the resilience indicators are a prominent feature of COMDEKS implementation from beginning to end. They are also a key feature of the adaptive management cycle that COMDEKS relies on, in which project results are used as a source of learning and innovation for future community efforts (UNDP, 2016).

3.2 Community consultation and baseline assessment

In November and December 2013, the Bingkai Indonesia Foundation conducted a baseline survey to determine conditions in the target landscape. Active participation of local communities and other key stakeholders in the baseline assessment was assured through literature reviews, field observations, community interviews, and a participatory assessment of community resilience. The assessment used the resilience indicators to help measure and understand the resilience of the target landscape. Nine small group discussions and six individual interviews with village leaders were initially held. To foster women’s empowerment and their effective participation in the planning process, 24 of the participants were women, and two of the small group discussions were attended exclusively by women.

A baseline assessment workshop was subsequently held with 25 participants, five of whom were women, using the resilience indicators. Following this, a second consultation was conducted (33 men, 4 women) to present the results, to discuss key problems and to identify activities that could contribute to the long-term sustainability of the target landscape. Some of the main areas of concern identified were the lack of access to freshwater, the adverse impacts of overuse of chemicals, the need for greater ecosystem and biodiversity protection, particularly of monsoon forest tree species and mangroves, as well as local crop varieties, and the need for increased agricultural/aquaculture innovation and knowledge (see Fig. 6) (UNDP 2016).

Figure 6. Mapping Semau Island resources and communities during the Baseline Assessment

3.3 Landscape Strategy and community-led landscape projects

The baseline assessment and community consultation gave rise to the COMDEKS Indonesia Landscape and Seascape Strategy, which sets out a slate of four Landscape Outcomes and associated indicators to measure progress toward these outcomes. It is the most critical element of the landscape planning process, where landscape communities generate a vision of what a more resilient local landscape would look like and determine what actions would be required to realize this vision (UNDP 2016). In the case of Semau Island, the target area is classified as a seascape due to its small island characteristic, and the concept of a seascape consists of land and marine management based on terrestrial governance. This long-term plan strives to improve the social and ecological resilience of small island and coastal communities as well as local and surrounding ecosystems through community-based activities, incorporating the conservation of terrestrial and coastal and marine areas – as stipulated in Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 – into the core objectives of the participatory Indonesia Landscape and Seascape Strategy (UNDP 2017a).

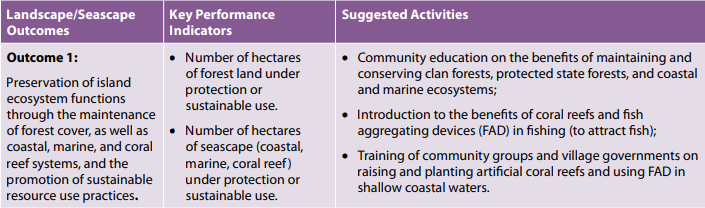

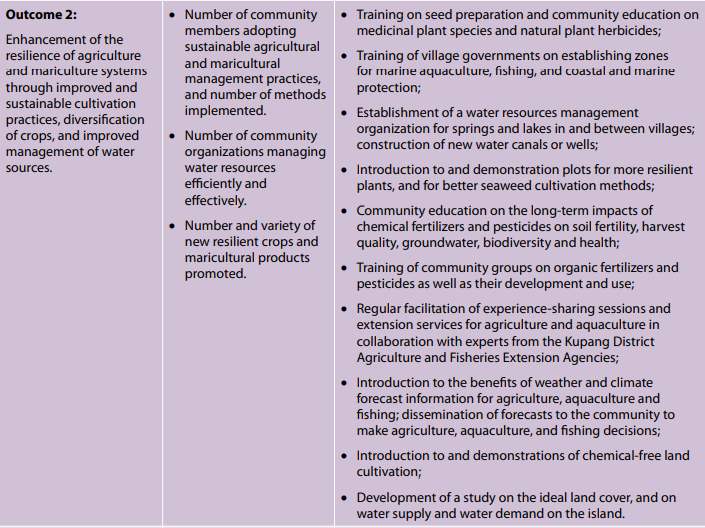

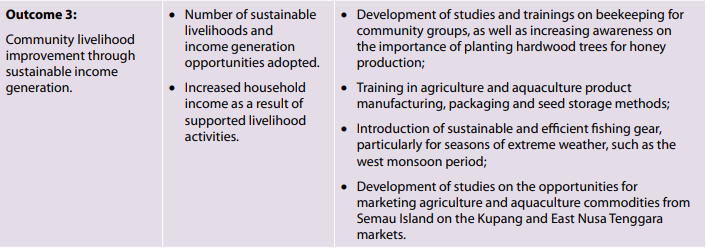

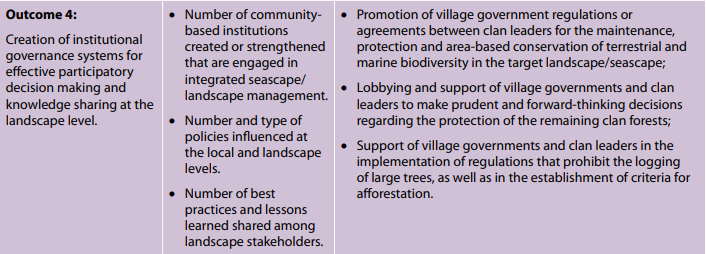

Table 1 lists the four Landscape Outcomes around which the strategy is built, the performance indicators that are used to measure progress toward these outcomes, as well as a number of activities that would contribute to the accomplishment of each Resilience Outcome to guide the selection of local projects GEF SGP Indonesia 2014; UNDP 2016).

Table 1. Landscape outcomes, indicators, and suggested activities from the Indonesia Landscape and Seascape Strategy

3.4 Achievements and impacts to date

Improving water management practices and promoting organic agriculture: Supported initiatives have brought improved agricultural practices that increase water access and decrease the use of agricultural chemicals. These include the establishment of a water conservation area that integrates tree planting with increased access to water by communities and improved irrigation systems. Village water committees have also been formed in each participating village. At the same time, 12 organic agriculture demonstration plots have been established, with crops including bananas, eggplant, capsicum, tomatoes, watermelon, sorghum, and red onions. A concerted effort to increase market access for organic crops in off-island markets is also underway. The combination of better irrigation (using both sprinklers and hand-held devices) and organic culture has led to zero chemical inputs by partner communities, a reduction in time spent irrigating crops, production of two crops per year instead of one, about 20 percent higher yields, as well as higher prices for organic produce. Adding to the success of these farm interventions has been the introduction of biogas systems in communities, which has resulted in reduced fuel wood use and related deforestation (see Fig.7).

Figure 7. Farmer woman in Semau Island, SGP/COMDEKS Indonesia

Improving marine management and seaweed culture: Marine Protected Areas, restored mangrove forests, and protected watersheds are important elements of resilient landscapes and seascapes. Supported marine interventions on Semau Island have focused on better management of the shoreline, improvements in seaweed cultivation, and restoration of mangroves, which were heavily cut to expand seaweed farming (see Fig.8). One major advance in terms of decreasing environmental impacts has been the imposition of restrictions on the extraction of beach sand, particularly in Batuinan Village, where a guarded portal was installed to limit sand mining in the area. Meanwhile, improvements in the growth and processing of seaweed have led to higher quality and quantity of seaweed for wholesale, and the development of seaweed-related secondary products has added value to the seaweed farming enterprise. Mangrove restoration is just beginning.

Figure 8. Sustainable seaweed farming practices, SGP/COMDEKS Indonesia

Establishing new institutions and networks: A range of new institutions and networks have been established in different Semau Island communities. These, along with environmental education in schools, have acted as a key mechanism to increase local environmental awareness and planning. More importantly, these new institutions have created governance platforms for community members to act on this increased awareness. Perhaps the most important new institutions are local Environmental Forums, which have been formed in seven communities. These forums include participation of customary authorities, community leaders, community groups and government authorities. They were established at the village level to ensure restoration of damaged ecosystems and to build a system for the continuing sustainability of these ecosystems. These local forums also participate in inter-village meetings so that issues of broader concern can be discussed and planned for in a collaborative manner.

Negotiating new agreements to protect community resources and local biodiversity: Taking into account the local clan-based land tenure structure in Semau Island, the formation of Environmental Forums and other new institutions has resulted in a variety of new environmental commitments by local clan leaders, village governments, and community members. These agreements cover a wide range of activities from watershed protection, irrigation and agricultural production, to seaweed farming and mangrove restoration. For example, in Batuinan Village, community members have agreed to declare a 3-ha water catchment area as a conservation zone, with the landowners agreeing not to lease this land for other purposes and community members agreeing to limit the number of private wells in the surrounding area in order to raise the water table. In line with local clan customs, these agreements have been fostered as customary oaths – instead of written laws – demonstrating a good example of how communities manage their land in a participatory manner based on spiritual values. In addition, village members have agreed to plant some 1,650 mahogany trees in their family gardens to regenerate local forest cover. Village churches in Batuinan have even agreed that couples getting married should each plant two trees in their home gardens. In Uitiuhana Village, villagers established a nursery to raise endemic tree seedlings to be planted on an 11-ha area donated by the clan leader. A draft agreement accompanying this tree-planting effort specifies nursery and forest management rules (trees cannot be cut for 20 years) and a monitoring system. Overall, about 67 hectares of monsoon forests have been conserved through community initiatives and agreements.

Mapping local environmental governance leaders: Little time has passed since the implementation of COMDEKS projects, so changes in the quality of local environmental governance cannot be assessed yet, although it can be said that the inclusion of women and youth has improved. To help in assessing governance changes, PIKUL (a local NGO) has produced a comprehensive baseline that, among other things, mapped 93 local leaders and social innovators (69 men and 24 women), including landowners, clan leaders, community leaders, community groups, and government. The map provides an important overview of the ecosystem of actors with decision-making power regarding the utilization of resources in villages, gardens, forests, water, coasts and marine areas. It aims to support future assessments of changes in governance quality as well as efforts to carry out area-based conservation of terrestrial and marine biodiversity and community resources at the local and landscape level (UNDP 2016).

4. Conclusions: progress at the landscape level

The establishment of so many local environment-focused community groups and the forging of a considerable number of formal, written environmental commitments at the village level is evidence of a strong participatory trend among Semau Island communities in environmental governance. As yet, this interest is mostly confined to local village matters, and is also mostly segregated into clan and ethnic groups. To date there has been little mixing among the two different ethnic groups, who tend to live in different areas and work in different enterprises (UNDP 2016).

On the other hand, project partners are continuing to meet to share lessons among themselves, and there has been robust support from government and clan leaders of all supported projects promoting landscape resilience. The seven different Environmental Forums have established a mechanism for inter-village meetings to discuss issues that reach beyond the village level, which could be considered the beginning of an island-wide landscape community to protect local biodiversity and community resources. Moreover, the multi-stakeholder nature of these forums brings together community and clan leaders with government officials from the Ministry of Forestry and the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, which manage the Marine National Recreation Park covering almost the entire coastal areas, and the Sawu Marine National Park located in the south and south-east waters, respectively. These forums create a fertile environment for future collaboration and exchange between the customary conservation areas governed by community leaders and the surrounding government-protected areas. They can also serve as a good example with replication and upscaling potential in other regions with similar governance structures.

5. Key messages and lessons learned

Figure 9. Community discussion on local environmental issues and governance

A number of valuable lessons learned were derived from supported projects’ activities. In the early stages of project conception, mapping of actors, governance structures and social innovators to understand responsibilities and roles of stakeholders in the target landscape significantly contributes to successful project design and implementation. It helps the project partners to develop a clear understanding of the current arrangements, identify areas for improvement, implement innovations and monitor progress.

The baseline assessment highlighted that addressing current problems seemed more important to the local community than anticipating future risk. As resilience measures are often perceived as generating only longterm benefits without immediate improvements to daily challenges for rural livelihoods, community consultations and discussions with individuals and groups about current challenges are a vital part of the participatory landscape approach supported by COMDEKS. Assigning facilitators from grantee NGOs and CSOs to small groups, and arranging individual and group discussions throughout project implementation, significantly helps with the collection of data, which can be used as supporting elements to facilitate the SEPLS resilience assessment, in addition to applying the Indicators of Resilience. Moreover, using demonstration sites is instrumental in raising the interest of stakeholders in new approaches, concepts and technologies and helps generate buy-in from local leaders and landlords who are critical to governance reforms on the local and landscape level (see Fig. 9) (UNDP 2017b).

Addressing governance issues is a critical pillar of improving landscape resilience. Revitalizing traditional values blended with human rights values is an important process to promote an inclusive dialogue among stakeholders. Dialogue on equity together with landscape and seascape control needs to be stimulated, including discussion of details on how shared values will be implemented in landscape management. Approaching such issues in an integrated manner is critical to conserving biodiversity and promoting sustainable livelihoods through landscape approaches. In the case of Semau Island, water supply had to be increased to boost agricultural yield, and in order to achieve this, certain agreements had to be formed with landlords who control the watersheds. In this context, agricultural productivity is a governance issue as much as it is a technical one relating to farming methods. Establishing environmental forums and water committees supported transparency and accountability around the projects in Semau Island, and has been instrumental in developing new rules and brokering agreements. These agreements have not only helped to retain customary arrangements, but also to make them more robust and less open to the vagaries of individual landlords. In addition, they promote intra- and inter-community dialogue. In this context, however, it is key to facilitate a common understanding towards long-term goals among customary leaders, clan members, community members and village governments towards sustainable landscape management. At the same time, promoting goals of individual stakeholders is the key towards collaboration (UNDP 2017b).

The NGO conducting the ex-post baseline assessment at the end of the COMDEKS project cycle used a technique called the Most Significant Change to collect stories from stakeholders throughout the target landscape. This technique was instrumental in identifying and documenting what stakeholders at the local and landscape level saw as the most significant change—in terms of resilience improvements—due to supported project activities. Field observations, interviews, focus group discussions, photographs, and video recordings were used to capture and record these stories, which were then used as part of the overall participatory evaluation procedure to assess project accomplishments, alongside resilience indicator scoring (UNDP 2018).

Acknowledgements

Funded by the Japan Biodiversity Fund, the COMDEKS Programme (2011-2016) is a unique global effort implemented by UNDP in twenty countries, in partnership with the Ministry of Environment of Japan, the CBD Secretariat, and the United Nations University – Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability. Working through the UNDP-implemented GEF Small Grants Programme (SGP), COMDEKS builds the capacities of community organizations to take collective action for adaptive landscape management in pursuit of social and ecological resilience.

References

Badan Pusat Statistik 2009 – 2012, Kecamatan Semau Dalam Angka, BPS Kabupaten Kupang.

GEF SGP Indonesia and Bingkai Indonesia Foundation 2014, Country Programme Seascape Strategy for Community Development and Knowledge Management, (COMDEKS) Indonesia.

Soetedjo, P, Aspatria, U, Surayasa, MT & Rachmawati, I 2009, Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Alam dan Lingkungan di Pulau Semau, Yayasan KEHATI, Jakarta.

UNDP 2016, A Community-Based Approach to Resilient and Sustainable Landscapes: Lessons from Phase II of the COMDEKS Programme, UNDP, New York.

UNDP 2017, Community Action to Achieve the Aichi Biodiversity Targets: The COMDEKS Programme, UNDP, New York.

UNDP 2017, Landscape Governance in Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes: Experiences from the COMDEKS Programme in Ecuador, Ghana, and Indonesia, UNDP, New York.

UNDP. 2018. Assessing Landscape Resilience: Best Practices and Lessons Learned from the COMDEKS Programme. UNDP, New York.

United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies (UNU-IAS) 2013, Indicators of Resilience in Socio-ecological Productions Landscapes (SEPLs), Policy Report, UNU-IAS, Yokohama.

UNU-IAS, Bioversity International, IGES & UNDP 2014, Toolkit for the Indicators of Resilience in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS).

Yayasan Pengembangan Pesisir dan Laut (YPPL) & The Nature Concervancy (TNC) 2011, Pemetaan Partisipatif Taman Nasional Perairan Laut Sawu, Final Report, YPPL, Kupang.