Conserving a Suite of Cambodia’s Highly Threatened Bird Species

03.05.2014

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) & Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS)

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

03/05/2014

-

REGION :

-

South-Eastern Asia

-

COUNTRY :

-

Cambodia

-

SUMMARY :

-

Cambodia supports globally important populations of wide-ranging, large-bodied bird species that are threatened by agricultural intensification and expansion, trade-driven hunting and chick/egg collection at nest sites. To address this problem of escalating biodiversity loss in the Northern Plains and Tonle Sap Lake and Floodplain and encourage community participation, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and partners designed a project with three financial incentive schemes. With funding from CEPF provided through the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot investment, WCS expanded the project to new sites and species to improve the project’s long-term financial viability and to increase the role of local civil society partners. The goal was to secure core populations of a suite of globally threatened bird species at four sites in Cambodia through a series of innovative conservation interventions focusing on providing direct incentives to local communities, namely payments for birds’ nest protection, improved value chains for “wildlife friendly” produce and ecotourism development. Another goal was to strengthen the capacity of local organizations to engage in long-term conservation efforts for the bird species.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Cambodia, financial incentives, ecotourism, birds

-

LINK:

Project Description

To secure core populations of a suite of thirteen globally threatened bird species at four sites in Cambodia, WCS implemented a series of innovative conservation interventions focusing on providing direct incentives to local communities. The project arose from work already being undertaken by WCS and its partners in Cambodia since 2000, and received US $699,125 in financial support from CEPF from October 2009 through June 2013 as part of CEPF’s initial investment in the Indo-Burma Hotspot.

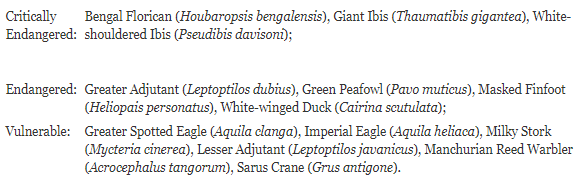

The project was designed to address threats to 13 priority species:

Figure 1: Nesting Endangered greater adjutant (Leptoptilos dubius) at Prek Toal. © Eleanor Briggs/WCS

The threats, highlighted by CEPF’s ecosystem profile for the Indo-Burma Hotspot, to these and other bird species include agricultural intensification and expansion, trade-driven hunting and chick/egg collection at nest sites. An additional threat is the lack of institutional capacity among civil society organizations charged with protecting these species.

The project had four components, three of which provided local communities with direct financial incentives to ensure that populations of the targeted globally threatened bird species, while the fourth focused on capacity-building.

Through earlier work, WCS had already developed the three innovative financial incentive schemes based on direct payments to local communities in return for conservation action. The CEPF-funded project expanded the four components to new sites and species, to improve their long-term financial viability and to increase the role of the local civil society partners. In addition, the capacity-building efforts were meant to ensure the long-term sustainability of the project’s components.

These four components included:

- Implementing community-based ecotourism that links revenue directly to long-term species conservation at various sites in the Northern Plains, at the Ang Trapeang Thmor (ATT) Sarus Crane Reserve, and in the Bengal Florican Conservation Areas (BFCA). This aimed to link revenue received from local community-based tourism enterprises directly to long-term species conservation through an agreement between the communities and local authorities that stipulates that tourism revenue is subject to the villagers agreeing to manage habitats through a village or site land-use plan and a no-hunting policy.

- Developing wildlife-friendly farming schemes, including locally branded “Ibis Rice,” in the Northern Plains and the BFCAs. This initiative encourages farmers to engage in conservation by offering them a premium price for their rice (about 10 percent above otherwise market value) if they agree to abide by conservation agreements that are designed to protect the areas used by the Critically Endangered waterbirds and other globally threatened species. The participating farmers agreed to a set of conservation regulations that limited agricultural expansion and prohibited hunting.

- Supporting a birds’ nest protection program at Prek Toal Core Area of the Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve where communities are offered financial incentives for protecting nests to reduce trade-driven hunting.

- Increase the capacity among the three partner civil society organizations (CSOs) – the Sam Veasna Center for Conservation (SVC), Sansom Mlup Prey (SMP) and Centre d’Etude et développement Agricole Cambodgien (CEDAC) – which are integral to the operation of the financial incentive schemes.

Accomplishments

Benefits for participating communities – The project directly benefitted more than 450 households across the landscapes, with many communities receiving increased income from the three financial incentive components.

Component 1: Ecotourism

In return for the local communities safeguarding the forest and protecting the rare species, the ecotourism scheme established at each village includes:

- A community conservation fund set-up on an incentive basis to maximize the tourists’ chances of seeing the target birds, usually $10 per person if one or more of the target species is seen and half this if not. At Tmatboey, this was set at $30 if one or both ibis species is seen and half this if not.

- Payments for services rendered either through a guesthouse fee (e.g. cooking, cleaning, etc.) or directly by guests (e.g. laundry).

- A community-based Conservation Management Committee (CMC) that is responsible for the organization of all tourism activities within the village, from bird guiding to the maintenance of a community guesthouse, and organizing the use of the community conservation fund for local development projects that have been chosen by the community.

These mechanisms help to ensure that income is transparently and equitably shared among households, and maximizes the number of villagers directly involved. The management system ensures that there is a high degree of local ownership for the project and that a large proportion of the financial benefits are captured by local people.

CEPF funding allowed expansion of ecotourism to Prey Veng, Sambour and Prolay Commune. Some funds were also used to co-finance parts of a vulture restaurant at Dongplat. In all cases, WCS facilitated the development process and provided training including bookkeeping, development of rules and regulations for the CMC, established rules for deciding expenditure and criteria for recruitment of villagers to tourism positions. The roles of all service providers were clearly defined during the process. All tourism promotion, guide training and bookings are now undertaken by the SVC, while the CMCs control all aspects of tourism management within the villages.

All nine villages participating in the ecotourism program exhibited sustained growth in the numbers of tourists visiting the sites despite some dips due to the global economic problems. In Sambuor, the number of tourists increased by 32.5 percent from 2011-2012 to 2012-2013. The amount of revenue generated by these visitors also increased throughout the project term, and the village development funds accrued were used to construct a new road in the village. Other participating villages used the funds to build libraries and repair a pagoda.

Component 2: Wildlife-friendly farming

The project established a supply chain for Ibis Rice, linking participating farmers in the Tonle Sap Inundation Zone with points of sale in Siem Reap and Phnom Penh. WCS and SMP worked together to form Village Marketing Networks at two villages and CEDAC provided training to participating farmers to improve agricultural efficiency and profitability of the crop.This initiative provides payments for forest protection based on premiums for agricultural products, particularly Ibis Rice. Farmers were encouraged to engage in conservation by offering them a premium price for their rice, about 10 percent above otherwise market value, if they agree to abide by conservation agreements that are designed to protect the areas used by the target species. This included no cutting of the forest, no illegal hunting and no use of agro-chemicals on their fields. These agreements are enforced by a locally-elected natural resource management committee, which is composed of representatives from the village and helps guarantee a high degree of local ownership.

The Ibis Rice scheme expanded with CEPF’s support to six additional villages, with the number of farmers involved rising from 12 in 2008-2009 to 216 in 2012-2013. Over the same period, the total amount of paddy purchased by the scheme has risen from 7.72 tonnes to 282.70 tonnes, causing the total annual benefit paid to participating farmers to increase from $1,325 in 2008-2009 to $7,908 in 2012-2013.

By the end of the project, Ibis Rice was on sale in 29 restaurants and hotels (19 in Siem Reap and 10 in Phom Penh), 31 supermarkets and was being purchased regularly by 20 other commercial customers.

Figure 2: Community members filling a sack with Ibis Rice. © Eleanor Briggs/WCS

Component 3: Birds’ Nest Protection

This component addressed the threat of collection of eggs and chicks for the trade market by making conditional payments to local people to protect nests. CEPF’s support allowed WCS to consolidate the program that was already operating in the Northern Plains and expand to Prek Toal in the Tonle Sap.

Under the program, nests were located by local people or community rangers contracted by WCS seasonally to undertake research. A permanent protection team was then established, which remained in place until the last chick fledged or until the eggs hatched. Participants were paid for reporting a nesting site and for their work on a protection team. Nests were deemed to have failed if they became unoccupied prior to fledging. Monitoring staff investigated all cases of nest failure to determine the cause, and payments were not made if nests failed due to human disturbance or collection.

At Prek Toal, the birds’ nest protection program expanded from 12 community rangers in 2003 to 32 in 2013. In the Northern Plains, the program benefited approximately 100 households each year and protected 2,981 nests of 11 species, from which 5,379 chicks fledged successfully.

Capacity strengthened in communities and CSOs – Throughout the project, WCS improved the capacity of 32 community-based organizations to map, develop rules and regulations and manage natural resources and land. The project focused on raising awareness and building capacity for biodiversity management through a mixture of formal training sessions and on-the-job mentoring in sustainable livelihood activities and natural-resource use. Overall, it is estimated that more than 20,000 community members benefitted from the project’s activities.

Of the three local partner CSOs, SVC and SMP have both shown significant growth in various measures of enterprise development, with SVC managing all ecotourism promotion, guide training and bookings, and SMP providing buying, milling, packing and distribution services for Ibis Rice by the end of the project. SVC is now fully financially viable, and a significant portion of their revenue is reinvested in conservation management activities at the various project sites.

Positive impact on priority species – Many of the targeted globally-threatened bird species saw population increases throughout the project term.

At Prek Toal, the Endangered greater adjutant (Leptoptilos dubius) increased by 157 percent from 2007 to 2012, from 77 nests to 198 nests; and the Vulnerable lesser adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus) increased by 14 percent from 2007 to 2012, from 253 nests to 289 nests. In the Northern Plains, the Critically Endangered white-shouldered ibis (Pseudibi davisoni) increased from one nest in 2002 to seven in 2012.

Challenges

Making a direct financial link between the economic well-being of the communities affected by the needs of conservation and the conservation objectives themselves – The project sought to further test the argument supporting financial incentive schemes for local communities to participate in conservation, to understand the mechanisms necessary and to overcome the difficulties involved. To encourage participation, the project allowed communities involved to have direct control over the services provided (tourism, rice production or nest protection), rewarded communities directly for the provision of those services, and linked continuing provision of financial incentives directly to a healthy conservation status.

What was key was that the financial rewards for those involved were linked directly to the conservation outcome, not through an indirect pathway; if the outcome (reduced hunting of endangered species, reduced habitat clearance, etc.) was not achieved, then no payments were made. Each had a rigorous monitoring system to measure the conservation outcomes and ensure that the link between conservation success and financial incentives was maintained.

Motivating communities and encouraging positive behavior toward conservation – Constant contact with the communities was vital and should be a part of all community-based natural resource management projects. To achieve this, advisors and social mobilizers were employed and spent long periods of time on the ground with the local communities. This frequency of contact helped build high levels of trust, capacity and motivation, which in turn facilitated the change in people’s mindsets and behaviors and brought about the success of the three financial incentive schemes.

Keys to Success

Using positive results to garner attention – Producing results successfully on the ground helped to draw the attention of senior politicians to the project’s aims. In fact, the senior minister for the environment became interested in the project after Tmatboey – a village participating in the ecotourism initiative – won the United Nations Development Programme Equator Prize in 2008. After making a visit to the village, the senior minister requested a further six sites to be identified and developed for nature-based tourism.

Engaging the government – The close liaison between government, an international NGO, and national civil society was particularly successful in enabling the complex requirements of the activities to be met smoothly while providing the Ministry of Environment and the Forestry Administration with unique insights into the needs of the local people and examples of how to work with them to achieve important conservation goals. By empowering existing government management structures rather than creating parallel ones, the project appears to have been successful in developing effective government engagement, participation and motivation.

Developing a replicable model to achieve sustainability – The project was designed to be part of a much longer process, with structures in place to support its planned achievements after its end since WCS and its partners will continue to implement the three financial incentive schemes.

“The structures that were in place prior to CEPF’s support were strengthened over the term of this project, and additional investment will allow further replication and enable sustainable conservation. Over the next five years, we plan to empower the community management committees to increase the extent to which they are involved in protected area management, increase local community incomes from conservation and in doing so, bring conservation interventions, such as ecotourism, Ibis Rice and the bird nest protection program to a point of financial and organizational sustainability,” said Tom Clements, director of the WCS Cambodia Program.

The three direct payment initiatives have all already been replicated at a local level, but the model can be used to expand the three financial incentive schemes to new villages within the current work areas or to new regions within Cambodia. This would help bring benefits to other globally threatened species as well as to new rural communities. CEPF will continue to support WCS to refine and amplify these approaches during its second investment phase, from 2013 to 2018.

Website links:

http://www.cepf.net/Pages/default.aspx

Recommendation:

Report of the Final Evaluation Mission: http://www.cepf.net/SiteCollectionDocuments/indo_burma/Edwards_WCS_CEPF_Final_Evaluation.pdf

CEPF Final Project Completion Report:

http://www.cepf.net/SiteCollectionDocuments/indo_burma/FinalReport_WCS_CambodiaThreatenedBird.pdf