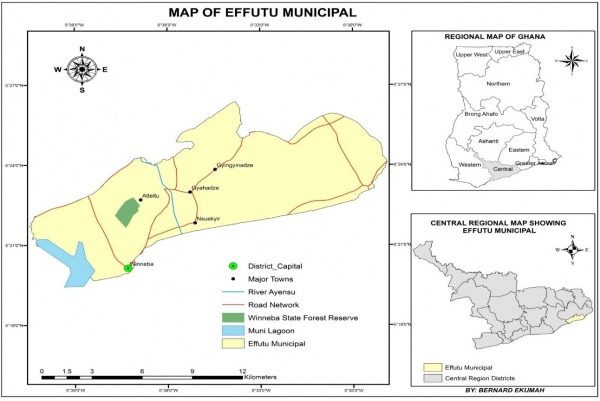

Community sacred forest in the Effutu traditional area, Central region, Ghana

25.08.2016

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

A Rocha Ghana

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

25/08/2016

-

REGION :

-

Western Africa

-

COUNTRY :

-

Ghana (Central Region)

-

SUMMARY :

-

In recent times, the implementation of traditional natural resource management and conservation methods has declined because of various factors, including weak traditional regulations, increasing population, and adoption of Western lifestyles. In Ghana, the implementation of policy directives and frameworks has resulted in certain areas currently being managed by communities, notably the Community Resource Management Areas framework, which demarcates an area for the protection of wildlife resources. An example is the community sacred forest in the Effutu traditional area. Interestingly, for the preservation of cultural heritage, the Effutu traditional area has over the last 300 years been designated a forest reserve for the protection of bushbuck for an annual hunt to celebrate the Aboakyir festival. However, currently, because of weak implementation of regulations and anthropogenic activities, resources at the designated hunting ground have dwindled, in particular, the continuous presence of bushbuck for the annual hunt. The “Restoration of Community Sacred Forest to Enhance Socio Ecological Landscape in the Effutu Traditional Area, Ghana” project therefore aimed to restore the ecological integrity of the site to enhance biodiversity conservation while preserving the cultural heritage of the Effutu people. This study highlights the significance of collaborative engagement as a tool for revitalizing and conserving threatened socio-ecological production landscapes. Using conservation education to ignite behavioral change in favor of natural resource conservation, 5.43 ha of degraded area was replanted, and the income levels of community members enhanced, thereby reducing their dependency on the forest for their livelihood. A fauna survey confirmed the presence of bushbuck, although the population is estimated to be very low.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Aboakyir festival, Bushbuck, Biodiversity, Cultural heritage, Effutu traditional area

-

AUTHOR:

-

Jacqueline Kumadoh, A Rocha Ghana

-

LINK:

-

https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:5769/SEPLS_in_Africa_FINAL_lowres_web.pdf

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.