Community Forestry in Nepal

27.12.2011

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Nepal

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

27/12/2011

-

REGION :

-

Southern Asia

-

COUNTRY :

-

Nepal

-

SUMMARY :

-

Community Forestry is increasingly recognized as a means for promoting sustainable forest management and restoring degraded forests for enhancing the forest condition as well livelihoods of low income people and forest dependent communities worldwide. It also promotes community rights to forests, enhances forest sector governance and local democracy along with mitigation of adverse environmental and climate change effects. Nepal has a well-documented history of over 30 years in community forestry and has been regarded as a model demonstrating the sometimes difficult paradigm shift from government-controlled forestry to active people’s participation. The Forest Act 1993 provided a clear legal basis for community forestry, enabling the government to ‘hand over’ identified areas of forest to CFUGs in Nepal. Some 1.23 million hectare forest out of 5.5 million hectare of total forest area has been managed under community forest with active participation of more than 14000 Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs) in various parts of the country. Patale CF, for example, was almost barren prior to being handed over to a CFUG and now is a fully stocked forest with lots of flora and fauna. CFUGs are managing forests with different silvicultural and management activities. Benefits accrued from forests are utilized for forest management, livelihood improvement, and social and community development activities. Indeed, community forestry and the Patale CF in particular is now widely perceived as having real capacity for making an effective contribution towards addressing environmental, socioeconomic and political problems in Nepal .

-

KEYWORD :

-

Community Forest, Community Forest User Group (CFUG), community development, governance, Handover, Livelihood, Silviculture, Sustainable Forest Management

-

AUTHOR:

-

Mr. Shankar Adhikari, permanent resident of Rupse-4 Palpa, is currently working as Forest Officer in District Forest Office Lalitpur under Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation Nepal. He has completed his graduation in Forestry from Institute of Forestry Pokhara in 2009 and is keenly interested in Forestry, Biodiversity and Ecological services issues. The role of forests and biodiversity in climate change adaptation and mitigation is also another field of his interest.

Back Ground

Community forestry has achieved broad global acclaim over the past three decades as a successful model for natural resource management that is innovative, people-centered and effective. It is increasingly recognized as a means for promoting sustainable forest management and restoring degraded forests, for enhancing the livelihoods of low income people, forest dependent communities, for promoting community rights to forests, for enhancing forest sector governance and local democracy, and for mitigating the effects of climate change.

Nepal, as one of the first countries to experiment with community forestry, has now come to be widely recognized as being at the forefront of its development and has perhaps made greater progress than many other countries in establishing it as the cornerstone of its forest sector policy. It has a well-documented history of over 30 years in community forestry internationally, and it is regarded as a model demonstrating the sometimes difficult paradigm shift from government-controlled forestry to active people’s participation -one that is observed with keen interest for lessons that can be learnt and applied elsewhere. It is now widely perceived as having real capacity for making an effective contribution towards addressing environmental, socioeconomic and political problems. This case study deals with overview of community forestry in Nepal with an illustration of Patale Community Forest.

Evolution of Community Forestry Policy, Programme and Legislation

The failure of a centrally controlled bureaucratic system of classical forestry, and the existence of informal indigenous forest management provided the impetus for institutional innovation in Nepal’s forestry sector. Successive refinement of partnership arrangements between local communities and the state forest agency based on practices in the field, and mutual assessment of the results has led to the growth of community forestry.

The initial phase of community forestry in Nepal was geared towards assigning responsibilities and rights of local forest management to the village level political bodies’ i.e Panchayat with the enactment of the Panchayat Forest Rules and the Panchayat Protected Forest Rules, 1978. It was based on protecting and planting

trees to meet the forest product needs of the local people based on the principle of ‘gap analysis’.

Three years of rigorous study and consultation in the preparation of the Master Plan for the Forestry Sector (MPFS), in addition to the first national level workshop on community forestry held in 1987 laid the foundation for handing over forests to groups of traditional forest users so that they could meet their basic forest product needs and at the same time conserve these forests. Reorientation of foresters was also considered essential for the sustainable management of these community forests. The MPFS further stressed that participation of local communities in decision-making and benefit sharing was essential for the conservation of forest management.

The endorsement of MPFS in 1988 and the political regime change in 1990 were instrumental in the formulation of new forest act in 1993 and forest regulations in 1995. By the early 1990s, however, continued experiential learning had started to highlight deficiencies in the legislative framework under which the community forestry model was being implemented. In particular, the key role of the Panchayat as a local institution began to be questioned. Panchayat were often large (geographically and in terms of population) and tended to be dominated by the traditional elite in rural society (wealthier, better educated, male and high caste). It was found that actual management of community forest and day-to-day decision-making on how the forest was to be developed and used would improve if they were undertaken by those people most directly affected by such decisions and prepared to contribute time and inputs into what they considered as their local resource. Thus, the concept of ‘forest users’ arose, i.e. those local people who traditionally used a particular patch of forest. Subsequently, community forestry became based around the community forest user groups (CFUGs) rather than the panchayat. Much effort during the early 1990s thus became focused on basing community forestry at the community level and seeking ways to bring such disparate groups together into CFUGs.

The Forest Act 1993 provided a clear legal basis for community forestry, enabling the government to ‘hand over’ identified areas of forest to CFUGs. The procedures were later detailed in the 1995 Forest Regulations, backed by the Community Forestry Operational Guidelines 1995. According to the Forest Act and the associated Forest Regulations, CFUGs are legal, autonomous and corporate bodies having full power, authority and responsibility to protect, manage and utilize forest and other resources as per the decisions taken by their assemblies and according to their self prepared constitutions and operational plans (with minimal scope for interference from the state forestry agency). Although all benefits from community forests would go to the CFUGs concerned, the land legally remained part of the state.

Important characteristics of formal CF legislation are:

- All accessible forests can be handed over to users without any limitation on area, geography and time

- Land ownership remains with the state, while the land use rights belong to the CFUGs

- All management decisions (land management and forest management) are made by the CFUGs

- Each member of the CFUG has equal rights over the resources

- Each household is recognized as a unit for the membership

- CFUGs will not be affected by political boundaries

- Outsiders are excluded from access

- There are mutually recognized user-rights

- There will be an equitable distribution of benefits

- The State provides technical assistance and advice.

Status of Community Forestry in Nepal

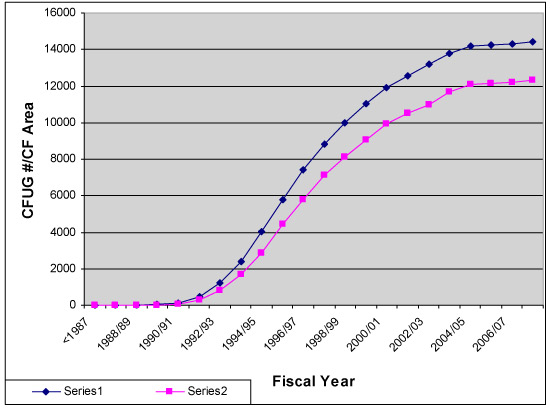

Figure 1: Handing Over CF over time

| Total land area of Nepal | 14.7 million ha |

| Total forest area | 5.5 million ha |

| Potential community forest area | 3.5 million ha |

| Forest area under community forestry | 1.23 million ha or 22% of total |

| Forest area | |

| Total number of CFUGs | 14439 |

| Women-headed CFUGs | 805 |

| Total number of households’ | 1.66 million or 33% of |

| Total households |

(Source: Gautam 2010)

Patale Community Forest

Fig 1: Community Forest with surrounding settlement and forests

Patale Community Forest (CF) is sandwiched between two community forests, namely Kafle CF and Padali CF in Lamatar Village Development Committee (V.D.C) ward number 1, situated in Lalitpur district just 11 km from Kathmandu, capital of Nepal. It is located at 270′ 27′ north, 270′ 37′ east latitude and longitude, respectively.

The community forest consists of 104.6 ha land covering 162 households within a community forest user group (CFUG) with 881 total populations in which 430 are female and 451 are male members. The vegetation type is a mixed one with Chilaune (Schima castanopsis), Katus (Castanopsis indica) and Utis (Alnus nepalensis) as the dominant species. For sustainable management of the forest, it is divided into six blocks, all of which include a fire line to protect from forest fires. From the upper part of this forest scenic view of Kathmandu Valley as well as sunrise view can be observed.

Fig 2: Scenic view of Kathmandu Valley from the community forest area

Historical Background of Patle CF

Prior to 1970, forest conditions were very good with abundant vegetation including trees, shrubs, Non timber forest Products (NTFPs), Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs), different wildlife species and plenty of water sources.

After 1970, due to an increase in population pressure on the forest and a lack of sufficient source of income for the people to their livelihoods, anthropogenic pressures in this forest rose tremendously, leading to massive deforestation and degradation of the forest. While forest was facing deforestation, in 1985 this forest faced the incident of big forest fire resulting complete loss of vegetation wildlife and converting forest into a denuded hill. Consequently, water sources also disappeared and people faced the problem of having to walk 8-10 hours even to transport a single jar of water. In order to control population pressure and conserve and protect the forest from further deterioration, with the initiation of local communities and the District Forest Office, local people were brought together for conservation and management of that forest and the forest was then handed over to the community forest user group (CFUG) to be managed as a community forest in 1994 after promulgation of the new Forest Act of 1993. Since then, it has been under the control of the community, the condition of the forest has improved, and people are benefitting from forest resources.

Governance

CFUGs have their own constitution, which governs the whole user group as well as the executive committee. Executive committee consists of 13 members with six females and seven males’ members. This executive committee looks after the decision making activities within the group.

The group has classified households into rich, medium, poor and very poor categories i.e. A, B, C, D. The classification is based on a well‐being ranking and the intention of conducting livelihood improvement program especially focusing on the C and D categories. Similarly, the CFUG also focuses its activities on improving governance status and promoting transparency and accountability. Moreover, it has created a separate monitoring and evaluation subcommittee and an account subcommittee.

Fig. 3: Constitution of Patale CFUG

How is the CFUG conserving and managing the forest?

The CFUG has prepared a five-year Community Forest Operation Plan (CFOP) with technical support from the forest technician of the district forest office. It encompasses overall features of the forest, growing stock, block division, forest management as well as silvicultural operation activities, conservation measures. It also covers provisions for the harvesting, utilization, selling, etc of forest products. CFUGs have to base their activities on this technical document for overall management of the forest. Once approved from district forest officer of district forest office, it becomes officially functional.

Based on the approved operational plan, the following forest conservation and management activities are being carried out by the CFUG:

- Protection of forest from uncontrolled grazing, illegal cutting, and forest fires, etc.

- Regular patrolling by CFUG members to conserve the forest and prevent illegal activities like encroachment, tree cutting, etc.

- Provisioning of forest watchers

- Grazing controls

- Hunting controls

- Rewarding informants informing about the activities of illegal activities within the CF

- Complete control over the collection of stone, sand, as well as all activities causing soil erosion, degradation as well as loss of biodiversity.

- Soil erosion controls

- Forest fire controls

- Punishment of persons conducting any activities against the rules of CF.

Major Silvicultural Activities

- Shrub land improvement: they have prepared a shrub land improvement demonstration plot

- Pruning

- Thinning and singling

- Planting and weeding

- Conversion of Pine Forest into Broadleaved forests.

- NTFP demonstration Plot

Fig 5: Plantation being carried out

Forest Product utilization and distribution:

The CFUG has made provisions within its Community Forest Operational plan regarding the collection procedures for timber, firewood, fodder, forage and leaf litter, as well as a timeframe for carrying out different forest management activities. They consume these products within the CFUG and if they have surpluses of these products, they can sell them outside the CFUG.

Major Vegetation and Wild life within CF

Major vegetation of this forest is as follows:

|

Nepali Name |

Scientific Name |

Category |

Uses |

| Bakle | Myrsine capitellata |

Tree |

Fuel wood and timber |

| Mauwa | Madhuka indica |

Tree |

Fuel wood, fruit and timber |

| Dhale katus | Castanopsis indica |

Tree |

Fuel wood, fruit and timber |

| Mansure katus | Castanospsis tribuloides |

Tree |

Fuel wood and timber |

| Utis | Alnus nepalensis |

Tree |

Fuel wood and timber |

| Kanphal | Myrica esculanta |

Tree |

Fruit |

| Chilaune | Schima wallichi |

Tree |

Fuel wood ,timber |

| Lankuri | Fraxinus floribunda |

Tree |

Fuel wood ,timber |

| Salla | Pinus roxburgii |

Tree |

Fuel wood, timber, leaf litter |

| Kaulo | Persea species |

Tree |

Timber and NTFP |

| Firfire | Acer oblongum |

Tree |

Fuel wood and timber |

| Chanp | Michelia champaca |

Tree |

Timber |

| Phalant | Quercus glauca |

Tree |

Timber and fodder |

| Painu | Prunus cerasoides |

Tree |

Ornamental, timber and fuel wood |

| Khari | Celtis tetranda |

Tree |

Timber, fuel wood, and pole |

| Saur | Saurauria nepaulensis |

Tree |

Timber, fuel wood, and pole |

| Lapsi | Chaerospondias axillaris |

Tree |

Fruit, timber, pole |

| Bains | Salix babylonia |

Tree |

Fuel wood , timber |

| Kalikanth | Myrsine semiserrata |

Tree |

Fuel wood , timber, fruit |

| Gogan | Sairauia grifthithi |

Tree |

Fuel wood , timber |

| Gurans | Rhododendron |

Tree |

Flower, fuel wood , timber |

| Mayal | Pyrus pashia |

Tree |

Fruit, fuel wood |

| Anselu | Rubus ellipticus |

Shrubs |

Fruit, living hedge |

| Chtro | Barberis aristata |

Shrubs |

Fruit, live fence |

| Dhasingre | Gaultheria fragrantissima |

Shrubs |

Fruit |

| Timur | Zanthoxylum armatum |

Shrubs |

Fruit, medicinal value |

| kimbu | Morus alba |

Tree |

Fruit, fodder |

| Alainchi | Amomum subulatum |

Shrubs |

Medicinal value |

| Bhyakur | Dioscorea deltoides |

Herbs |

Vegetable, fruit |

| Bantarul | Dioscorea bulbifera |

Herbs |

Vegetable |

| Kukurdaino | Smalax menispermoides |

Herbs |

Vegetable |

| Anp | Mangifera indica |

Tree |

Fruit, timber, firewood |

| Koiralo | Bauhinia variegata |

Tree |

Timber, firewood and vegetable |

| Tanki | Bauhinia purpurea |

Tree |

Timber, firewood |

| Sisnu | Urtica dioca |

Herbs |

Wild vegetable |

| Aru | Prunus persica |

Tree |

Fruit |

| Kainyo | Gravellis robusta |

Tree |

Ornamental value, timber, fuel wood |

| Amriso | Thysanolaena maxima |

Grass/herbs |

Fodder, soil conservation |

| Pipla | Piper longum |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Sugandhawal | Valeriana jatamansi |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Chiraito | Swertia chiraita |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Ghodtapre | Centella asiatica |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Manjitho | Rubia mahitha |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Charchare | Parthenocissus semocordata |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Neuro | Poa polyneuron |

Herbs |

Wild vegetable |

| Nim | Azadiracta indica |

Tree |

Medicinal value, timber, firewood |

| Ghiukumari | Aloe verra |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Tejpatta | Cinnamomum tamala |

Shrubs/Tree |

Medicinal, spice value |

| Pakhanbeda | Berginia ciliata |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Titepati | Artemissia indica |

Herbs |

Medicinal , antibacterial value |

| Lokta | Danphe bholua |

Shrubs |

Raw material for paper making |

| Angeri | Lyonia ovalifolia |

Shrubs |

Firewood |

| Bhalayo | Rhus sucedanea |

Shrubs/Tree |

Medicinal value |

| Ansuro | Justicia adhatoda |

Shrubs |

Medicinal and green manuring, mulching |

| Dhaturo | Datura stramonium |

Shrubs |

Medicinal value |

| Ganja | Canabis sativa |

Shrubs |

Medicinal value |

| Akansbeli | Cuscuta reflexa |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Gurjo | Tinospora reflexa |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Tarul | Dioscorea alata |

Herbs |

Wild edible fruit/vegetable |

| Chameli | Jasminum arborescens |

Herbs |

Ornamental value/ essential oil |

| Sungava | Dendrobium densiflorum |

Herbs |

Ornamental plant |

| Pipal | Ficus religiosa |

Tree |

Religious value |

| Bar | Ficus Bengalensis |

Tree |

Religious and timber/firewood value |

| Kurilo | Asparagus racemosus |

Herbs |

Medicinal value |

| Dhupi | Juniperus indica |

Shrubs/Tree |

Ornamental use |

Wildlife

Bears, different species of deer, leopards, pangolins, rabbits, wolves, snakes and bats are found within this forest. Similarly, various types of birds, reptiles, insects and mammals also occur here.

Sources of Income

- Water selling

Accordingly, in 2009 an agreement was made between the Bainsdobdevi drinking water company and the Patale CFUG to sell the tanks of water. The company provided a one-time payment of $1833 (NRS 132,000) to construct a water collection tank, which is constructed at private land of a CFUG member. There are 2 forms of agreement with this mechanism. The first one; the land owner renews an agreement every year with the company (tank owner), and secondly, the CFUG’s has a five-year agreement with the company (tank owner). The CFUG agreement as well as the total income and expenditure figures is transparent and accessible to all members. They made an agreement to pay $1.38 (NRs 100) /tank (6000 liters) in 2009, which will increase by 10% each year. Likewise, There is a payment made annually of $278 (NRs 20000) to landowner of water tank is located as well as $35 (NRS 2500)/month for a watcher. Demand for water varies depending on the season. According to Shiva Ram Paudel, a CFUG member, there is a high demand of up to 125 tanks per month during the dry season and a low demand of about 60 tanks per month during the rainy season. There is therefore variation in income ranging from $83 (NRs 6000) to $306 (NRs22000) per month. The agreement with the tank company has increased the financial resources of the CFUG, which then invests the funds into development interventions like forest conservation and management activities, support to local school construction / maintenance, water supply to users, road maintenance activities, etc. People perceive that water levels during the dry season are higher now compared to the past when the forest cover was very low. |

-

- Selling of Forest Products

- Membership fee and membership renewal

- Fee from visitors as well as researchers

- Support from different organizations

Now the CFUG has about US $1834 (NRs132000) in its fund

The CFUG has been profitably establishing linkages with different grassroots organizations like social clubs, the livestock management committee, the village development committee, the district development committee, media, range posts, NGOs, etc. This has enriched the group and its members across a wide range of issues.

Apart from forest conservation and management, CF has been contributing to different aspects of the community, as well as social development activities, as summarized as follows

- Institutional development of the CFUG

- Investment in community and local development: the CFUG has been supporting different types of development activities like road construction, community building construction, drinking water management, cultural preservation activities, ecotourism promotion, income generating activities, etc.

- Scholarships as well as stationery for low income, diligent and marginalized groups of students.

- Supply of forest products for different types of social development work

- Support for income generating activities like goat and pig raising for women and disadvantaged members of the CFUG, i.e. the previously described C and D categories

- Ecotourism promotion

Fig 7: CFUG members

Fig 8: CFUG office room

Future strategy

- Conducting different forest conservation and management activities.

- Conversion of pine forests into broadleaf forests for multiple benefits.

- Capacity building for CFUG members, especially those in the C and D categories.

- Planting of Lapsi (Choerospondis axilaris), multipurpose tree/fruit species, on 2 ha of land.

- Maintenance and promotion of NTFP demonstration plot.

- Commercial production of Bio Briquettes.

- As per the new CF guidelines of 2009, appropriate funding will be allocated for forest development, community development as well as poverty reduction programs; these activities will be implemented accordingly.

- In consideration of Tourism Year 2011 in Nepal, a variety of programs related to ecotourism promotion will be carried out.

- Initiative will be taken in implementing Local Payment for Environmental Services (PES) mechanisms.

- All benefits accrued from the forest will be distributed in an equitable way based on the well-being ranking and contributions of users.

- Recognizing the NTFPS (MAPs) within the forest, forest resource based enterprises will be conducted.

- In coordination with forest-related groups/institutions, NGOs, government agencies as well as donor agencies, programs related to forest development, institutional capacity enhancement and poverty reduction will be carried out.

Lessons Learnt

From the community forestry overview in Nepal as well as the Palate CF case study, in particular, the following lessons were learnt:

- First, community forestry is a viable resource management approach for conserving and improving the condition of forest resources if appropriate policy, policymaking processes and compliance mechanisms are maintained.

- Second, CFUGs can become effective and inclusive institutions, bringing together the rich and the poor, men and women, dalits (untouchable caste) and non-dalits, to address poverty and social exclusion by utilizing available resources for both subsistence and commercial purposes.

- Third, CFUGs, if given complete autonomy and devolution of power, can become viable local institutions for sustaining local democracy and delivering rural development services by creating income generating activities, and establishing partnerships with many NGOs and private sector service providers.

References:

Acharya, K. P. (2002) Twenty Four Years of Community Forestry in Nepal. International Forestry Review 4 (2): 149-146.

Anon (2007) Community forest Operation Plan (2007). Lalitpur: Patale Community Forest User Group, Lalitpur Nepal

Anon (2010) Community forest Constitution (2010). Lalitpur: Patale Community Forest User Group, Lalitpur Nepal

Gautam, M (2010) Community Forest Development Program. CF Bulletin 15 :2-3

Kanel, K.R. (2004) Twenty Five Years of Community Forestry: Contribution to Millennium Development Goals. Kathmandu, Nepal: 4th National Workshop on Community Forestry 2004

Kanel, K.R. (2009) Partnership in Community Forest: Implications and lessons. Pokhara, Nepal: Community Forestry International Workshop 2009

Pokharel B.K et al. (2007) Community Forestry: Conserving Forests, Sustaining

Livelihoods and Strengthening Democracy. Journal of Forest and Livelihood 6(2): 8-19