Community agrobiodiversity management: an effective tool for sustainable food and agricultural production from SEPLS

01.11.2016

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Community Agrobiodiversity Centre

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

01/11/2016

-

REGION :

-

Southern Asia

-

COUNTRY :

-

India (Wayanad, Kerala)

-

SUMMARY :

-

Different strategies that go beyond a conservationist approach are required for the management of SEPLS and their agrobiodiversity. It is necessary to actively integrate agrobiodiversity into the overall issue of sustainable development, giving equal consideration to the three dimensions of it – economic, ecological and social sustainability. The “4C” approach of the M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation has been an effective tool for conservation through sustainable management of production landscapes. This approach pays concurrent attention to the Conservation, Cultivation, Consumption and Commerce of components of agrobiodiversity. This case study from the Malabar region of the Western Ghats Mega Endemic Biodiversity Centre (Wayanad, Kerala) synthesises four complementary field action research programmes which have together contributed in mainstreaming the concepts of SEPLS in the policy and developmental planning of local self-governments. These programmes are presented here as four separate cases which followed different methodologies and actions. A seed care movement centred on rice has saved a large number of indigenous landraces cultivated in Wayanad. A detailed socio-ecological appraisal of paddy lands has helped researchers, people and policy makers to value the agroecosystem. The multi-level education, communication and training programme over a period of around 15 years has lent a hand to the people and local self-governments in devising a sustainable agrobiodiversity management plan.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Community agrobiodiversity management; Genome saviours; SEPLS; Western Ghats; 4C approach

-

AUTHOR:

-

Nadesapanicker Anil Kumar and Parameswaran Prajeesh, M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Community Agrobiodiversity Centre

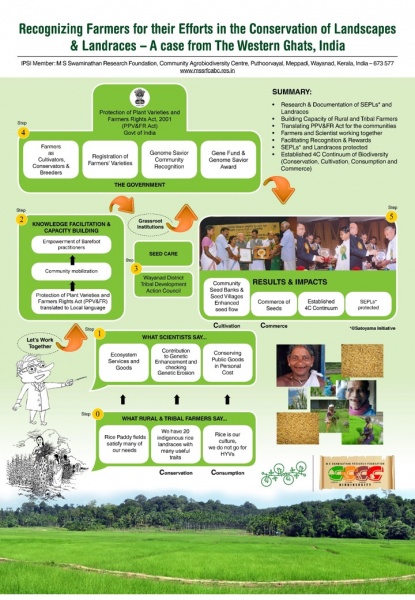

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Introduction

Resource use practices followed in SEPLS by communities including indigenous people that are often poor farmers, herders or fishermen have received wide recognition in international documents, such as the Convention in Biological Diversity (CBD) and the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA). Nagabhatla and Kumar (2013) observe that biodiversity conservation and management today is characterised by an important divide. On the one hand, there are classical conservation approaches concentrating on in-situ conservation in protected areas and ex-situ modes under the auspices of (mostly) governments. On the other hand, there is the practice of biodiversity in agricultural landscapes (on-farm) being managed by local communities. Community management efforts, which revolve around age-old traditional knowledge, practices and beliefs, help in better maintenance of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Agrobiodiversity preserved in such production landscapes has a critical role to play in dealing with the issue of under-nutrition. Hence dynamic conservation of agrobiodiversity needs to be placed as a high priority in the national development agenda for leveraging nutrition in agriculture and alleviating poverty and malnutrition (Kumar et al. 2015, p. 474). Unfortunately, the poverty-ridden custodians of agrobiodiversity are increasingly confronted with severe socio-economic constraints, which render maintenance of the socio-ecological services difficult (Swaminathan 2000, p. 117). It is also given that on-farm conservation offers a unique opportunity to link up conservation objectives with poverty. Farmers participate in conservation initiatives only if these activities support their livelihood strategies (Méndez, Giessman & Gilbert 2007, p. 148).

India is one of the most agrobiodiversity-rich countries of the world with over 160 crop species with hundreds of varieties, 325 crop wild relatives and around 1,500 wild edible plant species, as well as diverse domesticated animals, including birds (National Academy of Agricultural Sciences 1998).After CBD, necessary policies and measures came into force for conservation and sustainable use of India’s agrobiodiversity (Nayar, Singh & Nair 2009; Ministry of Environment and Forests2009). Two specific measures are national legislation, namely the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act of 2001 and the Biological Diversity Act of 2002.Though these efforts have proven that the strength and opportunities of India are heading in the right direction, the attempts however have not led to any large scale conservation or enhancement of agrobiodiversity on-farm in the country. On-farm management of agrobiodiversity, in production landscapes of the Western Ghats, a biodiversity hotspot and a UN-accredited World Heritage Centre, has become difficult due to an array of reasons. Kerala, from where this case study is prepared, has very specific regulations to conserve production landscapes, the wetland paddy fields. The Kerala Conservation of Paddy Land and Wetland Act of 2008does not allow the conversion of paddy land. Despite all the regulations provided under the act, paddy fields are being converted extensively for other purposes across the state. It is in this context that the interventions in community agrobiodiversity management of the M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF) over nearly two decades need to be synthesised and analysed for replication and up-scaling. The 4C approach [note: The integration of the 4C dimensions of genetic resource management—conservation, cultivation, consumption and commerce. The 4C framework as visualised by Professor M. S. Swaminathan includes: (i) enhancement and sustainable use of biodiversity that comprises in situ, on-farm and ex-situ conservation involving seed bank and community gene banks of varieties; (ii) promotion of low external input sustainable agriculture; (iii) food security and nutrition through revitalisation of traditional food habits; and (iv) creating an economic stake in conservation for concurrently addressing the cause of conservation and livelihood security through value addition and marketing methods] adopted has been an effective tool for conservation through sustainable management of production landscapes. This approach pays concurrent attention to the Conservation, Cultivation, Consumption and Commerce components of agrobiodiversity. Out of the many credible programmes, four relevant cases from the Malabar region of the Western Ghats Mega Endemic Biodiversity Centre (Kerala) are synthesised here.

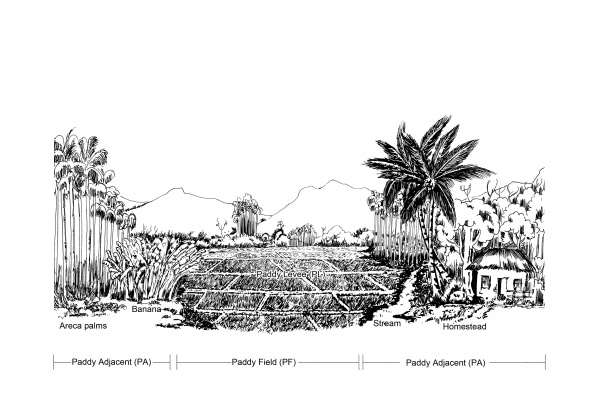

The centre of action – Wayanad District in Kerala

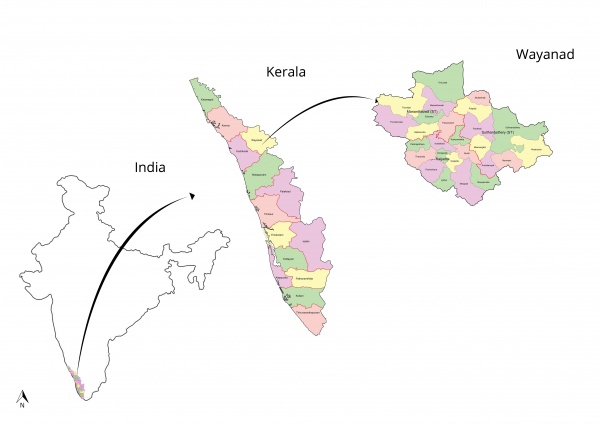

Wayanad is a hilly terrain in southern Western Ghats and lies at an average altitude of 750 metres above sea level (Figure 1). The district of 2,136 square kilometres is unique for its rich wealth of flora and fauna and for the diverse cultures that inhabit the land. Wayanad is a high range agro-ecological zone having moderately distributed monsoons (Kerala Agricultural University 2011). Narrow valleys surrounded by low range undulating hills and steep slopes characterise typical paddy fields in Wayanad (Figures 2&3). The total geographic area is 212,966 hectares with a total cropped area of 174,190 hectares (Department of Economics and Statistics 2015). The contribution to the state’s foreign exchange earnings through cash crops (pepper, cardamom, coffee, tea, ginger, turmeric, rubber and areca nut)is significant (Kumar, Gopi& Parameswaran 2010, p. 141). The genetic diversity in paddies is also notable with over 20 landraces cultivated that have peculiarities in response to flood, drought, pests and diseases (MSSRF 2001; Parameswaran, Narayanan & Kumar 2014, p. 705). Floristic exploration of the district has recorded nearly 49% of the flora of the Kerala State and more than 10% of the flora of India. This study has reported a total of 596 endemic taxa in which 15 are exclusive to the district (Narayanan 2009). Nair (1911) explains that the name Wayanad is believed to be derived from Wayanad meaning upper land or from Vayalnadu meaning land (nadu) of paddy fields (vayal) or from Vananadu meaning land of forests (Vanam). Wayanad is notable for its large Adivasi [note: Adivasiis an umbrella term for indigenous or tribal population groups in India (Rath 2006)] population, which accounts for 18.53% and is the largest among the districts in the state (Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner 2011). They can be broadly classified into farming communities (Kurichya, Mullukuruma), agricultural labourers (Paniya, Adiya), artisan communities (Uralikuruma) and hunter-gatherer communities (Kattunaikka).Others are Thachanadan mooppan, Karimbalar, Pathiya and Wayanadan Kadar. Wayanad also has the largest settler population in Kerala (Nair 1911; Indian Institute of Management 2006).

Figure 1. Location of Wayanad (from MSSRF archive).

Figure 2. Paddy and associated landscapes – a view from Wayanad (Photo from MSSRF archive).

Figure3. A model landscape (Parameswaran, Narayanan & Kumar 2014, p. 711, sketch by Jayesh P. Joseph, MSSRF).

Methodology, results and discussion for the four cases synthesised

Case 1, Seed Care Movement for saving the landraces and landscapes

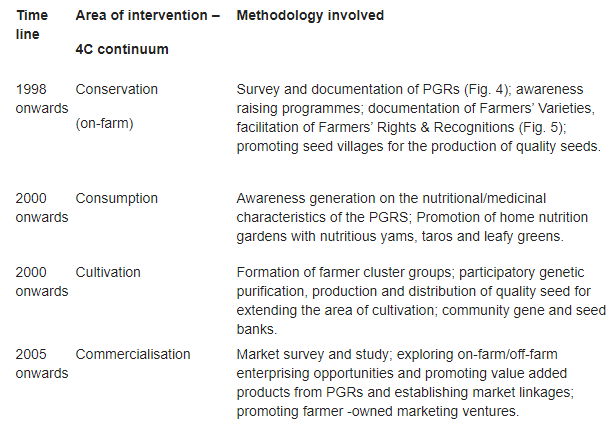

The idea of Prof. M. S. Swaminathan to have a conservation continuum—on-farm to ex-situ—has resulted in the establishment of a number of national level gene banks in many countries and the Svalbard seed vault (Swaminathan 2009). However, current global trends in the conservation of plant genetic resources (PGRs) are to work directly with farmers rather than through gene banks, and hence in-situ on-farm conservation has become more important, while ex-situ collections are considered only to be back-ups for PGR management. MSSRF’s community agrobiodiversity programme over the years has made concentrated efforts to study, devise and implement agrobiodiversity management centred on rice paddies in Wayanad (Table 1). Its seed care movement has promoted conservation of seeds of indigenous varieties of small-holder family farms. This movement has been facilitated since 1998 by involving major farming communities, especially the Kurichya, Kuruma, Pathiya and Wayanadan Chetty to promote the conservation and sustainable use of indigenous crop varieties, and later was taken up by four grassroot institutions [note: Wayanad Agricultural and Rural Development Association (WARDA) is an umbrella organisation of farmers and development practitioners from the district; JEEVANI is a farmers’ organisation for the conservation and cultivation of medicinal plant species; Wayanad District Tribal Development Action Council (WDTDAC) constituted by and for Adivasis has a motto to serve their sustainable development and SEED CARE, and is an association of traditional agricultural crop conservators] (Kumar, Parameswaran & Smitha2015).

Table 1. Methodology chronicle – 4C continuum in promoting the conservation and enhancement of agrobiodiversity and SEPLs of Wayanad (Kumar, Parameswaran & Smitha 2015)

The Seed Care movement has mobilised primarily rice farmers who cultivate traditional varieties, and clustered them into seed villages, to serve as seed banks. SEEDCARE has been spearheading the processes of community mobilisation, awareness generation for PGR management, quality seed production and management of seed and gene banks of traditional crop varieties. Farmer-participatory purification (Arunachalam 2000, p. 3) was adopted for selection and purification of seeds sourcing the expertise of lead farmers. Trainings were also provided, such as those on purification techniques, seed and grain management and mechanisation, to help the community in their efforts to conserve speciality varieties (Smitha2014;Kumar, Parameswaran & Smitha 2015).

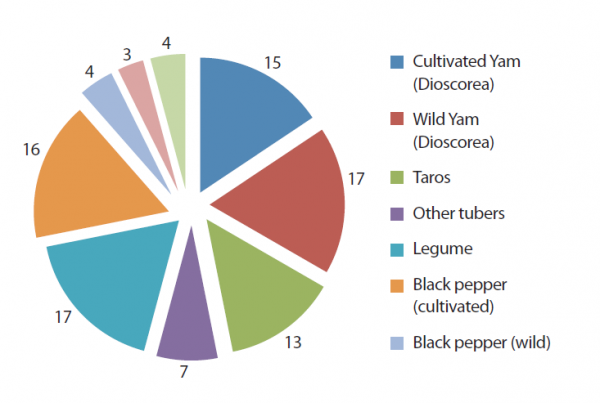

Among other crops yams and aroids used to serve as “life saving” crops during periods of seasonal and acute food scarcity. These are low water footprint and resilient crops that have the potential to help poor and marginal farmers adapt to the vulnerabilities of climate. MSSRF has recorded 30 to 40 cultivated varieties of them from Wayanad and adjoining regions (Varieties of Dioscorea alata, D. bulbifera, D. esculenta, D. pentaphylla, D. hispida, D. hamiltonii, D. kalkapershadii, D. oppositifolia, D. pubera, D. bulbifera, D. tomentosa, Colocasia esculenta, Alocasia macrorrizos, Xanthosoma sagittifolium, Amorphophallus companulatus, Maranta arundinaceaandCanna indica). The intervention began with a participatory research study to access traditional knowledge on wild edible resources, the gender dimensions of its management and present livelihood options (Narayanan, Swapna & Kumar 2004), as well as individual research on the yam varieties of Wayanad (Balakrishnan 2009). The studies showed that many tribal and rural families continue to conserve a wide range of plants to meet their food needs. Women are more skilful in managing the surrounding landscape and are the chief knowledge-holders and conservationists. Following these studies, the experience in promoting sustainable utilisation of the indigenous and traditional agricultural seed wealth of the Wayanad district showed that improving the capacities of the small and marginal farmers would result in improved decision making in land use and thereby improved agroecosystem governance (Table 2).

Figure 4. Number of crop varieties maintained in germplasm garden of MSSRF and conserved through the seed care movement, excluding paddy varieties (Kumar, Parameswaran & Smitha 2015).

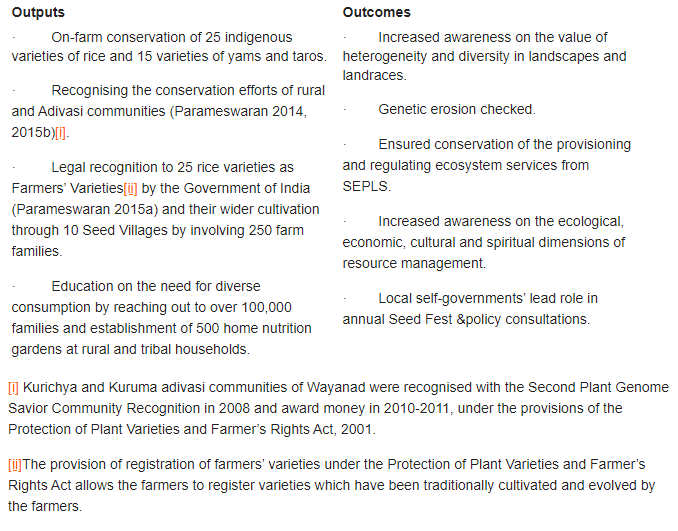

Table 2. Major outputs/outcomes of the seed care movement (Kumar, Parameswaran & Smitha 2015)

Figure 5. MSSRF’s efforts in recognising the farmers for their contribution in the conservation of Plant Genetic Resources (Community Agrobiodiversity Centre 2013).

Case 2, promoting cultivation of medicinal and aromatic varieties of rice

The rice conservation programme was launched in recognition of the importance of rice fields and landraces (Box 1) from the point of view of agrobiodiversity. The farmer participatory seed purification (Arunachalam 2000, p. 3) and multiplication programme has produced tonnes of quality seeds of these varieties. The System of Rice Intensification (SRI) method of cultivation was also introduced in the district. Later, in consultation with different stakeholders including farmers, local self-governments, agricultural departments, scientists and practitioners, policy documents were prepared on the possibility of promoting rice cultivation in the district. Adding efforts to the preliminary interventions, speciality rice varieties were selected for mass multiplication and market linkages were created for generating economic stake in conservation (eds. Nampoothiri et al. 2007).

Promoting wider cultivation of Navara- a ‘2500 year-old’ medicinal rice

Among the rice varieties cultivated in Wayanad, the cultivar known by the names Navara or Njavara and Chennellu is considered a high-value medicinal rice. Documents show that it has been in cultivation in Kerala for about 2,500 years since the time of Susruta, the Indian pioneer in medicine and surgery. Navara is reported to have multiple uses and to be a very nutritious, balanced and safe food for people of all ages. Rice paste of this variety is recommended for external application to rejuvenate muscles and thus offers vitality. A detailed survey was undertaken for this variety and four distinct ecotypes within Navara were reported for the first time. Then efforts turned to conservation of Navara in its full genetic variability on-farm and revival of rice paddies. The market linkages created for this speciality rice were welcomed and more farmers have started cultivating Navara (eds. Nampoothiri et al. 2007). Our successful pilot clinical study has also elucidated the effective use of the rice against neuro-muscular disorders (Guruprasad et al. 2014, p. 63).

Box1. Some of the high-value farmers’ rice varieties of Wayanad and adjoining regions (Kumar, Gopi &Parameswaran 2010, p. 144)

|

· Veliyan (MannuVeliyan): Drought and flood tolerant |

Case 3: a socio-ecological appraisal for devising a sustainable agrobiodiversity management plan

This transdisciplinary research taken up in 2010 [note: Project BioDIVA (http://www.uni-passau.de/en/biodiva/home/), a collaborative research project of Leibniz University and University of Passau, Germany with M S Swaminathan Research Foundation] has had direct links to the policy decisions on conservation and sustainable utilisation of agrobiodiversity, looking into the causes and consequences of land use change in rice-based farming systems in Wayanad. Central to this framework was the integration of both academics’ and practitioners’ knowledge in order to find solutions to real-life problems. The erosion of rice agrobiodiversity in Wayanad was analysed from the disciplinary domains of ecology, economics, and social sciences. Conversion of rice fields to grow other crops or even for non-agricultural land use was assumed to be one of the major reasons for the erosion of agrobiodiversity in Wayanad (Figures 6&7). Studies have shown that factors such as cost of production, availability of agro-inputs and labour, family income, and marketing opportunities, all influence cropping decisions. Moreover, existing social structures, gender relations, family setups, culture, and education further interact with farmers’ decision making processes. In this context, the project has explored the socio-ecological complexity of the rice farming system. Ecological research has improved understanding of farmers’ ecological knowledge, their seed system and the plant diversity associated with rice ecosystems along a gradient of agricultural intensification and land use change. The economic study has assessed the factors that influence farmers’ decisions in regard to alternatives to rice-based farming systems. Furthermore, this included an evaluation of rice ecosystem services in comparison with alternative land uses. The social science component was aimed to analyse gendered knowledge, changes in power structures within families and the societal relations with nature concerning land use change (Chattopadhyaya et al. 2012; Arpke, Parameswaran & Werner 2013; Arpke et al. 2013).

Figure 6. Conversion of paddy field for alternate crops (Photo by Prajeesh Parameswaran).

Figure 7. Conversion of paddy field for housing purpose (Photo by Prajeesh Parameswaran).

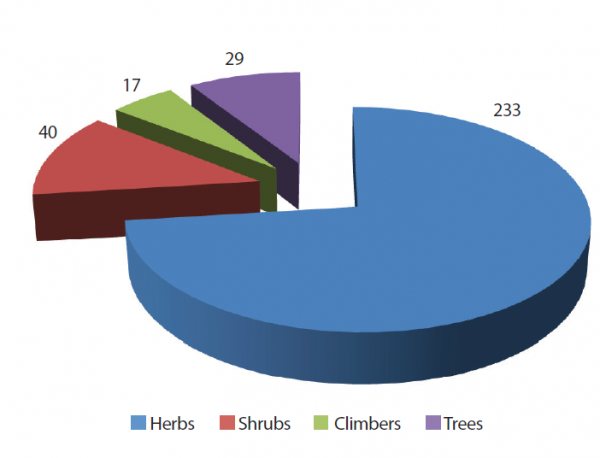

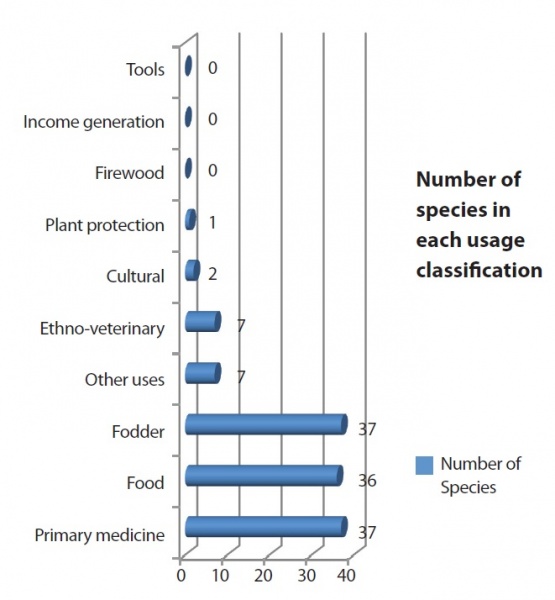

An exploration under this programme, with the participation of stakeholders of paddy lands (with Prior Informed Consent, Parameswaran 2013; Fig. 8& 9), has studied the floral diversity associated with the paddy land (Parameswaran, Narayanan & Kumar 2014, p.707) and summarises that the flowering plant diversity of paddy associated landscape is rich and harbours 15% of the total angiosperm species reported in the District (Figure10). As an agroecosystem, the rice fields also provide a range of tangible and intangible services to the local community (Figure11). Quoting Department of Economics and Statistics (1983&2013), Parameswaran, Narayanan and Kumar (2014, p. 712) have suggested acting urgently in response to the drivers of land use change that happens in these parts. An assessment of the impacts of agricultural practices and landuse change on communities of plants, spiders and leafhoppers of rice fields has suggested that cultivation practices and landuse change should be considered in strategies for sustainable agriculture since they are interlinked (Betz, Parameswaran & Tscharntke 2013).

Figure 8. Researcher interacting with farmer as part of the floral diversity study (Photo by M. K. Nandakumar, MSSRF).

Figure 9. Farmer consultations (Photo by Prashob P. P., MSSRF).

Figure 10. Number of species reported from paddy associated landscapes by habitat (Parameswaran, Narayanan & Kumar 2014, p.712).

Figure 11. Number of species and their usage classification – from paddy fields and paddy levees (Parameswaran & Kumar 2015).

An investigation among the Kuruma, Kurichya and Paniya tribal communities has showed that the socio-ecological system is highly modified. Deforestation is the major driver of environmental change, the loss of natural resources and consumption habits (Betz et al. 2014, p.578). The whole exercise aimed to generate transforming knowledge towards sustainable use of agrobiodiversity through a multi-lateral approach of action research and policy advocacy in a partnership mode. Regional and state level landuse visioning exercises, aimed to move away from problems toward a positive, pro-active, solution-oriented approach, were inspiring to the stakeholders including policy makers (Arpke, Parameswaran & Werner2013). Accordingly, the local land users and decision makers were enabled to assess the current situation and devise strategies for future land resource use.

Case 4: capacity enhancement programme for local self-governments in agrobiodiversity management

A prominent feature of the three key pieces of legislation that deal with sustainable management of India’s production landscapes namely, the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act 2001 (PPV&FRA), the Biological Diversity Act 2002 (BDA), and the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers’ (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act 2006 (FRA), is the greater recognition of the rights of tribal and local communities which are critical to the conservation, sustainable use and active enhancement of biological diversity. The PPV&FRA has specific provisions that recognise farmers’ rights to save, use, sow, re-sow, exchange, share or sell their farm produce, including the seed of a protected variety. The BDA identifies the right of local communities to equitably share the benefits arising out of the use of biological resources. Likewise, the FRA grants the right to access biodiversity and community rights to intellectual property and traditional knowledge related to forest biodiversity and cultural diversity.

These acts place considerable power in the hands of local self-governments, the Panchayath Raj Institutions (PRIs) in helping the implementation of the provisions of “community rights” outlined in them. For instance, the Forest Rights Act demands the Grama Sabha [note: The Kerala Panchayat Raj Act (1994) envisages a three-tier local self-governance system comprising a District Panchayat, Block Panchayat and Grama Panchayat (Village Panchayat). Under each Grama Panchayat, Grama Sabha is a body with all persons whose names are included in the electoral rolls relating to a village comprised within the area of a village panchayat and convened by the representative Panchayat member. It is a powerful and responsible grassroots body which helps and directs the three-tier system to work for people and development] to function for recognising forest rights and regulating access to forest resources. One of the envisaged utilisations of the Gene Fund provisions in the PPV&FRA is capacity building on ex-situ conservation at the local body level, particularly in regions identified as agrobiodiversity hot spots and for supporting in-situ conservation. BDA also demands the implementation of provisions through PRIs. However, even in a progressive state like Kerala a large majority of the elected members and officials of PRIs are deprived of the critical knowledge that is needed for developing biodiversity integrated developmental plans. Hence, the challenge was to empower the functionaries of local bodies to enshrine these provisions and integrate them into local development plans.

MSSRF undertook a genetic and legal literacy campaign at the PRI level soon after the BDA and rules came into operation in the year in 2004 in three agrobiodiversity hotspots with a core objective of empowering the elected member of PRIs to make decisions on access to genetic resources, benefit sharing and seed management. Kerala was the first state to setup the State Biodiversity Board and pioneered the implementation of the BDA. Likewise, Wayanad was the first district in Kerala to constitute Biodiversity Management Committees (BMCs) [note: The BDA warrants every local body to constitute a Biodiversity Management Committee (BMC) within its area for the purpose of promoting conservation, sustainable use and documentation of biological diversity including preservation of habitats, conservation of farmers’ varieties and breeds and chronicling of knowledge relating to biological diversity. BMC is a powerful body which decides on the sustainable utilisation of the bio-resources under its area and the equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the use of such resources. It can also act on local environmental issues including those related to land use] and complete preparation of People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBR) [note: As per the Biological Diversity Act (2002), PBR is to be mandatorily prepared and periodically updated by each local self-government documenting the biodiversity of their area and traditional knowledge associated with it, in a participatory mode. As a comprehensive database, PBR is envisaged as a powerful tool in the management and sustainable use of bio-resources] in all Grama Panchayats. It was MSSRF’s effort that contributed to PBRs in four Grama Panchayats in Waynad, Kerala before the state government’s efforts (Figure 11). The PBR model was synthesised from different models that were then available (Gadgil 1996, 2000) and adapted to local situations. Later, the methodology and format developed and adopted by MSSRF was recommended by the National Biodiversity Authority. MSSRF had done the translation of the BDA to Malayalam, the regional language, and also made an illustrated user-friendly manual of the act (Kumar et al. 2010, p. 46; MSSRF 2005).The model was also consulted upon by the Kerala State Biodiversity Board while they developed the PBR format based on the guidelines issued by Government of India (National Biodiversity Authority2013). Although the Wayanad district had formed BMCs in all the Grama Panchayats, the majority of BMC members were unaware of their roles, responsibilities and powers. Lessons learned from the rights awareness campaign and capacity building efforts emphasised the need for more grassroots level awareness and empowerment programmes for decentralised bodies to ensure effective implementation of legislationon agrobiodiversity and related community rights.

Figure 12. Release of PBR, Kottathara Grama Panchayat, Wayanad 2004 (Photo from MSSRF archive).

Conclusion

All of these cases in a bio-cultural heritage site like Wayanad intended to generate transforming knowledge towards sustainable use of agrobiodiversity and SEPLs through a multi-lateral approach of action research and policy advocacy in a partnership mode. The policy documents prepared out of these exercises have had a wide reach in regional, state, national and international consultations (MSSRF 2009, 2010; Werner & Nagbhatla 2013; Arpke, Parameswaran & Werner 2013; Arpke et al. 2013; Werner& Höing2014). Even though the Governments of India and Kerala have enacted various acts and implemented various schemes for promoting agrobiodiversity conservation and the management of production landscapes, these measures could not gather the desired results. The relevance of these four cases is so important at this juncture, where the conversion of agricultural land and dwindling diversity in genetic resources have become the biggest challenges to agrobiodiversity conservation at the farm level. Also, the initiative is important in view of the likelihood of climate change impacts. Based on these pilot efforts, MSSRF along with its grassroots institutions has fuelled a number of programmes in the district envisioning the knowledge sharing and conservation of agrobiodiversity by ensuring its sustainable and equitable use. One such programme is the Community Seed Fest initiated in 2015, the primary aim of which is to create awareness among farmers and other local communities on farmers’ and community rights related to biodiversity (Figures 12 & 13). From 2016 onwards, along with Kerala State Biodiversity Board, MSSRF has begun operating a five-year programme to strengthen five selected BMCs of the district and to help them in sustainable and equitable use of bio-resources. This programme is envisaged for the entire tenure of the newly constituted BMCs, the locally constituted environmental ‘watchdogs’ (Department of Environment and Climate Change 2013; Nandakumar 2013).

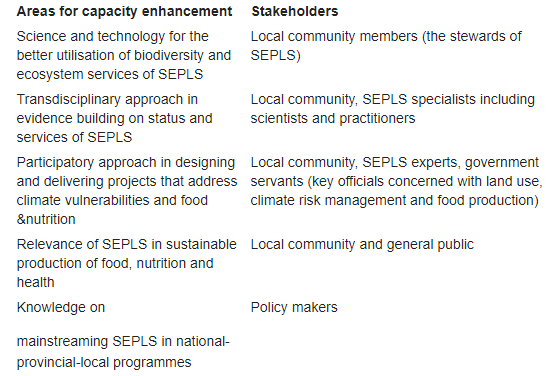

Our efforts suggest that different strategies are required for the on-farm management of agrobiodiversity and SEPLS that go beyond a conservationist approach. Some of the actions (especially for capacity enhancement) required towards this are suggested in Table3. Rather it is necessary to actively integrate agrobiodiversity into the overall issue of sustainable development, giving equal consideration to the three dimensions of it-economic, ecological and social sustainability. Conservation issues, cultivation knowledge, consumption awareness and commercial aspects all need to be integrated into one overarching policy strategy. Theoretically, this concept seems to be logical, but nevertheless, more examples of successful implementation on larger scales are needed.

Figure 13. A policy consultation as part of the Wayanad Community Seed Fest 2015, participated in by farmers, scientists and policy makers (Photo from MSSRF archive).

Figure 14. State Minister for Agriculture visiting the agrobiodiversity exhibition of Wayanad Community Seed Fest, 2015 (Photo from MSSRF archive).

Table 3. Capacity development actions required at the local level in SEPLS management (synthesised from successful models mentioned in the cases from Wayanad and different stakeholder meetings)

Achieving sustainable benefits that contribute to food, nutrition and health, as well as income and livelihood security of the poor and vulnerable communities that are traditionally the managers of SEPLS is one of the major objectives of the International Partnership on Satoyama Initiative (IPSI). Historically, SEPLS management has contributed to improved resilience of production landscapes and seascapes and achieved three globally beneficial outcomes, such as (i) ecological intensification, (ii) maintenance of biodiversity and (iii) a culture of sustainable consumption and distribution. Nevertheless, these outcomes are almost absent in the present day food and agricultural production system. This issue can be addressed by urging for a landscape/seascape approach in land use planning and optimising the use and deployment of agricultural biodiversity in production systems, as well as synergising the activities of a large number of actors working for sustainable food and agriculture production. An empowered IPSI member organisation platform can effectively link the IPSI activities with relevant players for encouraging innovations and transferring science and technologies that help in sustainable management of genetic resources and habitats. Finally, to conclude, there is a need for hand-holding of local institutions like community agrobiodiversity centres with democratically elected and empowered local self-governments to integrate the notion of SEPLS in real-life and livelihood actions and to mainstream its concepts.

Acknowledgements

Authors gratefully acknowledge Prof. M. S. Swaminathan for his vision and guidance in establishing the Community Agrobiodiversity Centre in Wayanad and for his continuous mentoring. The guidance provided by Dr. S. Balaravi, Former Advisor to MSSRF and Ms. Mina Swaminathan, Advisor to MSSRF is also acknowledged. The Executive Directors and other colleagues, especially of the Biodiversity programme of MSSRF are gratefully acknowledged for helping in bringing out the agrobiodiversity programme. We acknowledge the BioDIVA project, support and inputs by the colleagues of the BioDIVA research group (http://www.uni-passau.de/en/biodiva/home/). The support from the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, Government of India (Department of Science and Technology, Department of Biotechnology, National Medicinal Plants Board), UNDP’s Global Environment Facility and German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) is also acknowledged. Above all, we are indebted to the farmers of Wayanad, the custodians of agrobiodiversity, the genome saviours, the local self-governments who have partnered in our agrobiodiversity programme.

References

Arpke, H, Kunze, I, Betz, L, Parameswaran, P, Suma TR & Padmanabhan, M 2013, Resilience in transformation: A study into the capacity for resilience in indigenous communities in Wayanad, BioDIVA Briefing Note 2, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.uni-passau.de/fileadmin/dokumente/ projekte/biodiva/BioDIVA-BriefingNote2-2013.pdf>.

Arpke, H, Parameswaran, P & Werner, S 2013, Visions for Wayanad – The land of paddy fields, BioDIVA Briefing Note 1, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.uni-passau.de/fileadmin/dokumente/projekte/biodiva/BioDIVAhttp:// www.uni-passau.de/fileadmin/dokumente/projekte/biodiva/BioDIVA-BriefingNote2-2013.pdfBriefingNote2-2013.pdf>.

Arunachalam, V 2000, ‘Participatory Conservation: a meansof encouraging community biodiversity’, PGR Newsletter – FAO, Bioversity, no. 122, pp. 1-6.

Balakrishnan V 2009, ‘Ethnobotany, Diversity and Conservation of Wild Yams (Dioscorea) of Southern Western Ghats, India’, Ph.D. thesis, University of Madras, Chennai.

Betz L, Kunze, I, Parameswaran, P, Suma, TR & Padmanabhan, M 2014, ‘The Social – Ecological Web: A Bridging Concept for Transdisciplinary Research’, CURRENT SCIENCE, vol. 107, no. 4, pp 572-580.

Betz, L, Parameswaran, P & Tscharntke, T 2013, ‘Spidercicada-plant relationships in rice fields of changing Indian landscape’, in Abstracts of the Annual conference of the Society for Tropical Ecology: Tropical organisms and ecosystems in a changing world, Society for Tropical Ecology, Vienna, pp. 68, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.soctropecol.eu/PDF/gtoe_Wien_2013.pdf>.

Chattopadhyay, R, Gopi, G, Parameswaran, P & Kumar, AN 2012, ‘Conservation and equitable use of agrobiodiversity in Wayanad – An inter- and transdisciplinary research approach’, in Proceedings of Indian Biodiversity Congress, Narendra Publishing House, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, pp. 53–61.

Community Agrobiodiversity Centre 2013, Satoyama Initiative, viewed 15 February 2016, <https://satoyamainitiative.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/32.-MSSRFCommunity-Agrobiodiversity-Centre.pdf>.

Department of Economics and Statistics1983, Statistics for Planning, Department of Economics and Statistics, Government of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala.

Department of Economics and Statistics 2013, Agricultural Statistics, Department of Economics and Statistics, Government of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.ecostat.kerala.gov.in/index.php/reports/154.html>.

Department of Economics and Statistics 2015, Agricultural Statistics 2013-14, Department of Economics and Statistics, Government of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.ecostat.kerala.gov.in/docs/pdf/reports/agristat/1314/agristat1314.pdf>.

Department of Environment and Climate Change2013, Government Order-Entrusting BMCs to avoid Environmental Degradation at local level – Orders (in Malayalam), Department of Environment and Climate Change Government of Kerala, GO No.04/13/Envi., viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.keralabiodiversity.org/images/pdf/env_degredation.pdf>.

Gadgil, M 1996, ‘People’s biodiversity register: a record of India’s wealth’, Amruth, Spl. Suppl., pp. 1-16.

Gadgil, M 2000, ‘People’s biodiversity registers: lessons learnt’, Environment, Development and Sustainability, vol.2, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Netherlands, pp. 323-332.

Guruprasad, AM, Saravu NR, Shanthakumari, V, Sushma KV, Kumar, AN &Parameswaran, P 2014, ‘Navarakizhi and Pinda Sweda as Muscle-Nourishing Ayurveda Procedures in Hemiplegia: Double-Blind Randomized Comparative Pilot Clinical Trial’, The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 57-64.

Indian Institute of Management 2006, Wayanad initiative: a situational study and feasibility report for a comprehensive development of Adivasi communities in Wayanad, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.scribd.com/doc/4074255/Wayanad-Initiative>.

Kerala Agricultural University 2011, Package of Practices Recommendations: Crops, Kerala Agricultural University, Thrissur, 14th edition, p. 360.

Kumar, AN, Gopi, G & Parameswaran, P 2010, ‘Genetic erosion and degradation of ecosystem services of wetland rice fields: a case study from Western Ghats, India’, in Agriculture, Biodiversity and Markets. Livelihoods and Agro-Ecology in Comparative Perspective, eds S Lockie & D Carpenter, Earthscan, London, Washington DC., pp. 137-153.

Kumar, AN, Nambi, VA, Geetha Rani, M, King, EDIO, Chaudhury SS & Mishra, S 2015, ‘Community agro biodiversity conservation continuum: an integrated approach to achieve food and nutrition security’, CURRENT SCIENCE, vol. 109, no. 3, pp. 474-487.

Kumar, AN, Nambi, VA, Nampoothiri, KUK, Geetha Rani, M, King, EDIO 2010, BIODIVERSITY PROGRAMME Hindsights and Forethought, M S Swaminathan Research Foundation, MSSRF/MA/10/43, pp. 56.

Kumar, AN, Parameswaran, P & Smitha KP 2015, ‘Giving Breath to Dying Wealth – A Community Conservation Movement for Saving the Vanishing Crop Diversity of Wayanad’, in Biocultural Heritage and Sustainability, eds KP Laladhas & OV Oommen, Kerala State Biodiversity Board, pp. 118-134.

M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation2001, Phase – I Completion Report on Conservation, Enhancement and Sustainable and Equitable Use of Biodiversity, M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai, pp. 101.

M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation 2005, The Biological Diversity Act (2002) and The Biological Diversity Rules (2004), Malayalam Translation, M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Community Agrobiodiversity Centre, Wayanad, pp. 106, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://nbaindia.org/uploaded/docs/Bio_diversity_Act_malayalam.pdf>.

M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation2009, The Thazhava Plan of Action, Recommendations of the State-Level Policy Dialogue, January 2009, M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Community Agrobiodiversity Centre, Wayanad, pp. 20, viewed 15 February 2016, <https://www.mssrfcabc.res.in/assets/downloads/THAZHAVAPLANOFACTION.pdf>.

M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation2010, Thiruvananthapuram Declaration, Recommendations of the Policy Makers’ Consultation on Effective Community Management of Agrobiodiversity in an Era of Climate Change, M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Community Agrobiodiversity Centre, Wayanad, pp. 15, viewed 15 February 2016,<https://www.mssrfcabc.res.in/assets/

downloads/Trivandru-Declaration.pdf>.

Méndez, VE, Giessman, SR and Gilbert, GS 2007 ‘Tree biodiversity in farmer cooperatives of a shade coffee landscape in western El Salvador’, Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, no. 119, pp. 145–159.

Ministry of Environment and Forests 2009, India’s Fourth National Report to the convention on Biological Diversity, (Goyal, AK & Sujatha, A eds), Ministry of Environment and Forests, New Delhi, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.moef.nic.in/sites/default/files/India_Fourth_National_Report-FINAL_2.pdf>.

Nagabhatla, N &Kumar, AN 2013, ‘Developing a joint understanding of agrobiodiversity and land-use change’, in Cultivate Diversity! A handbook on transdisciplinary approaches to agrobiodiversity research, eds A Christinck & M Padmanabhan, Margraf Publishers, pp. 27-51.

Nair GC 1911, Wynad: its People and Traditions, Higginbotham & Co, Madras, viewed 15 February 2016, <https://archive.org/stream/wynaditspeoplest00goparich/wynaditspeoplest00goparich_djvu.txt>

Nampoothiri, KUK, Gopi, G, Smitha SN and Manjula C (eds) 2007, 10 Years of Community Agrobiodiversity Centre, M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, MSSRF/RR/07/15, pp. 52. Nandakumar, T 2013 ‘BMCs to act as environmental watchdogs’, HINDU, 22 June, viewed 15 February 2016, < h t t p : / / www. t h e h i n d u . c o m / n e w s / c i t i e s /Thiruvananthapuram/bmcs-to-act-as-environmentalwatchdogs/article4840956.ece>.

Narayanan RMK 2009, ‘Floristic study of Wayanad District giving special emphasis on conservation of Rare and Threatened plants’, Ph.D. thesis, University of Calicut, Kerala.

Narayanan, RMK, Swapna, MP & Kumar, AN 2004, Gender Dimensions of Wild Food Management in Wayanad, Kerala, Community Agrobiodiversity Centre & Utara Devi Resource Centre for Gender and Development, M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, MSSRF/RR/04/12, pp. 111.

National Academy of Agricultural Sciences 1998, India Policy Paper for Conservation: Management and use of Agrobiodiversity, Policy paper 4, National Academy of Agricultural Sciences, New Delhi, pp. 8, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://naasindia.org/Policy%20Papers/pp4.pdf>.

National Biodiversity Authority 2013, People’s Biodiversity Register – Revised PBR Guidelines (based on the guidelines issued by NBA in 2009) National Biodiversity Authority, Chennai, NBA/PBR/02, pp.64, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://nbaindia.org/uploaded/pdf/PBR%20Format%202013.pdf>.

Nayar, MP, Singh, AK, & Nair, KN 2009, ‘Agrobiodiversity Hotspots in India – Conservation and Benefit Sharing’. Vol.1,Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Authority, New Delhi, pp.2-3.

Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner 2011, Census of India 2011, Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Government of India, New Delhi, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/PCA/PCA_Highlights/pca_highlights_file/kerala/Exeutive_Summary.pdf>.

Parameswaran, P 2013, ‘Consent on cooperation and knowledge sharing – experience from the BioDIVA subproject agro-ecology’ in Cultivate Diversity! A handbook on transdisciplinary approaches to agrobiodiversity research, eds A Christinck & M Padmanabhan, Margraf Publishers, pp. 150-151.

Parameswaran P 2014, ‘Here are the Saviour of Plant Genomes’ KERALA KARSHAKAN E-journal, vol. 2, no. 7, pp. 12-15, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://fibkerala.gov.in/images/ejournal/2014/ej-dec14.pdf>.

Parameswaran P 2015a, ‘Farmers’ Rights to Seeds, Issues in the Indian Law’, Economic & Political WEEKLY, vol. L, no. 12, pp. 16-18.

Parameswaran P 2015b, ‘Leading from the front: Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act of India and the Plant Genome Saviors of Kerala’, KERALA CALLING, vol. 35, no. 8, pp. 28-30, viewed 15 February 2016, <https://issuu.com/ratheeshkumar2/docs/kc_june_2015>.

Parameswaran, P & Kumar, AN 2015, An account of the ‘useful weeds’ of wetland rice fields (vayals) of Wayanad, Kerala, M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Community Agrobiodiversity Centre, Wayanad.

Parameswaran P, Narayanan MKR and Kumar NA 2014, ‘Diversity of Vascular Plants Associated With Wetland Paddy Fields (Vayals) Of Wayanad District in Western Ghats, India’, Annals of Plant Sciences, vol.3, no. 5, pp. 704-714, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://annalsofplantsciences.com/index.php/aps/article/view/105/90>.

Rath, GC 2006, Tribal Development in India. The Contemporary Debate, Sage Publications, New Delhi, pp. 340.

Smitha, KP 2014, A focus on conserving traditional rice varieties, GRASSROOTS, Press Institute of India– Research Institute for Newspaper Development, Chennai, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.pressinstitute.in/file-folder/grassroot/November%20grassroots%202014.pdf>.

Swaminathan, MS 2000, ‘Government-industry-civil society: partnerships in integrated gene management’, Ambio, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 115–121.

Swaminathan, MS 2009, ‘Gene banks for a warming planet’, Science, vol. 325, no. 5940, pp. 517.

Werner, S & Nagabhatla, N 2013. Multistakeholder dialogue on land use change-Transdisciplinary approaches to address landscape transformation in Kerala, BioDIVA Briefing Note 4, pp. 6, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.uni-passau.de/fileadmin/dokumente/projekte/biodiva/BioDIVABriefingNote4-2013.pdf>.

Werner S and Höing A 2014,“Cultivating Diversity” Results from the national level dialogue Workshop, BioDIVA Briefing Note 5, viewed 15 February 2016, <http://www.uni-passau.de/fileadmin/dokumente/projekte/biodiva/BioDIVABriefingNote5-2014.pdf>.

The Biological Diversity Act, (No.18 of 2003, Gov’t of India).

The Kerala Conservation of Paddy Land and Wetland Act 2008 (Gov’t of Kerala).

The Kerala Panchayat Raj Act 1994 (Gov’t of Kerala).

The Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act (No.53 of 2001, Gov’t of India).

The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers’ (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act 2006 (Gov’t of India).