COMDEKS Project: Tukombo-Kande Region, Malawi

06.03.2017

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); Ministry of the Environment, Japan; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity; United Nations University (UNU)

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

06/03/2017

-

REGION :

-

Eastern Africa

-

COUNTRY :

-

Malawi (Nkhata Bay District)

-

SUMMARY :

-

The Community Development and Knowledge Management for the Satoyama Initiative Programme (COMDEKS) was launched in 2011 to support local community activities that maintain and rebuild target production landscapes and seascapes, and to collect and disseminate knowledge and experiences from successful on-the-ground actions so that, if feasible, they can be adapted by other communities throughout the world to their specific conditions. The programme provides small-scale finance to local community organizations in developing countries to support sound biodiversity and ecosystem management as well as to develop or strengthen sustainable livelihood activities planned and executed by community members themselves. The target landscape for COMDEKS activities in Malawi is the Tukombo-Kande area, located in Nkhata Bay District in northern Malawi, 330 km north of Lilongwe City.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Mountains, Agriculture, Erosion, Alternate livelihoods, Protected areas

-

AUTHOR:

-

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

-

LINK:

-

http://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:6012/communities_in_action_comdeks.pdf#page=102

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

The Landscape

Geography

The target landscape for COMDEKS activities in Malawi is the Tukombo-Kande area, located in Nkhata Bay District in northern Malawi, 330 km north of Lilongwe City. The target area is approximately 27,000 ha, and covers three Traditional Authority (TA) areas: Zilakoma, Malengamzoma, and Fukamapiri. The Dwambazi River forms the lower boundary, while the northern section extends up to the Kande Trading Centre. The climate of the area is fairly humid, with annual rainfall of 1400 mm and average monthly temperatures ranging between 20-28°C. Along the shore of Lake Malawi, however, the temperatures are modified by lake breezes. Elevations range from the lake shore plains of 400-550 m to the plateau of 800 m. Marshes and wetlands dominate the area along the lakeshore.

The Tukombo-Kande region is a scenic area composed of mountain ranges on the eastern stretch (with swaths of both protected and customary forests), cascading down into customary farmland and settlements areas. Wetland areas along the shores of Lake Malawi are rich in biodiversity, and support a number of fishing activities. Tukombo-Kande has been selected as the target landscape due to the potential for integration of fishing and farming communities with the rich Tonga (ethnic tribe) culture. The combination of biodiversity protection and trade center development creates the potential for successful projects in this region.

Biological Resources and Land use

The Tukombo-Kande landscape is very heterogeneous, characterized by mosaics of forest land, agricultural land, beaches, wetlands, and aquatic systems with many fish landing sites. Land use can be classified into five patterns: forest land, arable land, fallow land, grassland and homesteads. Grasslands found along the lakeshores serve as grazing land for goats.

Agricultural land is vast, with many different types of produce, including cassava, maize and cereals. The dominant crops in terms of land allocation are cassava, maize, groundnuts, sweet potato, rice, bananas and beans. However, the poor soils in the area are not able to support crops that have high nutrient demands, and are thus a limiting factor for agricultural production.

The area has two important forest reserves close to Kande (Kuwirwe and Chisasira), as well as a number of Village Forest Areas (VFAs). The tree and shrub species from the forests are used for firewood, medicinal uses, construction of canoes, and rafters for fish processing. The forests are habitats for different wildlife such as birds, rodents, warthogs, monkeys, hyenas, and antelopes. Fruit trees such as mango and orange trees are common on homesteads.

The wetlands near the shores of Lake Malawi are dominated by Ficus sycomorus, Syzygium cordatum, kamphalasa/mtatu and mgoza plants. The rivers have a variety of wildlife such as crocodiles and different fish types, while the lake has hippopotamuses. The most common fish making up the local catch are Usipa (Engarulicypris sadella), tilapia, and Copadichromis species. Different fishing gear, including seine nets, gillnets, and hand lines, are in common use. Fish are dried and sold at the fish landing sites.

Socioeconomic Context

The target landscape is predominantly an agricultural and pastoral rural area with relatively low population density and no large towns. According to the 2007/08 census, the Tukombo-Kande area has a population of approximately 58,000 people. The major ethnic groups in the area are Tongas (64%) and Tumbukas (33%), as well as tribes of Nkhonde, Chewa, Lomwe and Ngoni. The inhabitants have deep cultural traditions that have been used in the protection of biodiversity.

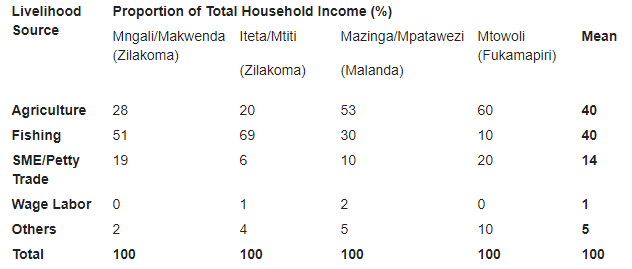

The major sources of income and livelihood support for the Tukombo-Kande area are agriculture, fishing and small businesses. Both farming and fishing contribute approximately 40 percent of household income, while small enterprises contribute around 14 percent. Less than 1 percent of total household income comes from formal sector employment (see Table M-1).

Table M-1. Sources of Household Income by Village in the Tukombo-Kande Region

Some 11,200 families in the area are involved in farming. Agriculture is largely a woman-dominated occupation, since men consider fishing to be more commercially attractive. The Tukombo-Kande landscape is unique as it has cassava as a predominant food crop. The farming communities mainly rely on the state Agricultural Development Marketing Corporation (ADMARC) and private dealers to buy and sell high-value agricultural outputs and inputs such as maize, rice or fertilizers, but the bulk of low-value crops such as cassava, sweet potato, and leafy vegetables are traded locally and not properly integrated into the urban markets. Commodity prices are extremely low at the peak season due to high supply, which does not match the available demand. Although the area has high potential for irrigated farming, irrigation is not common, and most crops are rain-fed.

Fishing is another major household activity. Just like agriculture, fishing is also seasonal in nature, with different fish species available at different times of the year, and the value of the catch varying by season. Fishermen make up to K97,600 (US$238) per day per landing, on average. Small-scale and household businesses are also an important additional income source, with a variety of wares sold in roadside stalls or open-air markets.

Nkhata Bay is an important tourism destination in Malawi. One important site is Chintheche, 15 km from the northern boundary of the landscape. There are several attractive beaches that are potential sites for tourism within the target landscape. However, important infrastructure to support a tourism industry, such as access roads, chalets, and health facilities, remain underdeveloped. In general, the road network in the area is poor, and the water and sanitation infrastructure are very limited. An additional economic obstacle is the lack of banking services and credit for local investment in better fishing gear, tourist facilities, or other economic development activities.

Cassava processing, typical livelihood activity in the target area, COMDEKS Malawi

Key Environmental and Social Challenges

The main environmental challenges confronting the Tukombo-Kande landscape are deforestation due to agricultural expansion, declining biodiversity, shifting cultivation, forest fires, overfishing, and overexploitation of tree resources for fish processing. Over the past 30 years, for example, significant changes in forest cover have taken place, with crops expanding at the expense of forest area due to a rapid increase in the practice of slash and burn agriculture and a simultaneous decline in the use of fallow periods. At the same time, an increase in the number of fishers has put pressure on the lake’s fish stocks and also caused a spike in wood use associated with fish drying and processing. Visible results of these pressures include low fish catches, increased soil erosion, and siltation in the Lake and rivers. High incidences of crop pests and disease outbreaks significantly reduce the yield of cassava and banana crops.

Population increase has been a major driving force of change in the landscape. The southern tip of the landscape has faced massive temporary settlements of fish mongers from Salima, Lilongwe and Kasungu districts, while the middle section has migrants from Karonga cultivating rice and tobacco. Increased population has resulted in encroachment on forest sites and overexploitation of forest resources for firewood, fish racks, canoe construction, tobacco racks, and other uses. Despite being rich in diversity, beautiful scenery, cultural heritage, historical monuments and other ecologically attractive features, community-based ecotourism has not developed significantly in the target area. Furthermore, inadequate water and sanitation infrastructure pose additional challenges for residents.

COMDEKS Activities, Achievements, and Impacts

Community Consultation and Baseline Assessment

Eleven communities took part in community consultations and the baseline assessment in order to determine conditions in the target landscape and engage local residents in the process of landscape planning. The effort was coordinated by Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Bunda College. The consultations were authorized by the local District Commissioner, who sought the participation of local traditional authorities—Chiefs and village headpersons—and sanctioned the participation of relevant government departments (Agriculture, Fisheries, Environment, Education, Planning, and others). The traditional authorities, in concert with a key NGO in the area, in turn mobilized the communities, including grassroots community groups engaged in agriculture, fish farming, and farm commodity trading. A draft map was created before the baseline assessment, but final agreement on the boundaries of the target areas was done with community participation.

To conduct the baseline assessment and score the resilience indicators, 12 different workshops were conducted, due to the diversity of the landscape, the number of different land uses, and the variety of tribes living in the area. For each meeting, local stakeholders included members of the Village Natural Resource Management Committee, village headperson or his/her representative, an agricultural officer, and two facilitators from Bunda College. In each community, two focus groups of 5-15 men, women, and youth were organized—one in the lowland, which is dominated by fishing activities, and the other in the upland, which has a more diverse mixture of agricultural activities and forest biodiversity. Scores on the resilience indicators were arrived at by consensus through the facilitated group discussions. In total, over 140 participants were directly involved in the community consultation and baseline assessment workshops.

Community members gather for a stakeholder consultation, COMDEKS Malawi

When tabulated, the results of the baseline assessment showed that the upper part of the landscape scored highly on ecosystems protection, while the sites very close to the lake were rated very low for social equity and infrastructure. The fish landing sites had inadequate social infrastructure for communication, water, education and health. Social equity and infrastructure underdevelopment were perceived as a main challenge for communities living very close to fish landing sites.

Microfinance opportunities were identified as a desired mechanism to improve social equity. Loans may be made to support business enterprises that have the added objective of environmental and livelihood diversification efforts such as improved market access of fish products, mango processing, apiculture, and rice milling and packaging. The development of irrigation was pinpointed as a strategy to improve crop production. Household food security may also be improved through promotion of small-scale livestock and dairy production.

Ecosystem protection is perceived as poor due to the threats from shifting cultivation, wildfire, and opening of new gardens due to migration of people from other sites, traditional brick-making and over-exploitation of forest resources. Illegal pit sawing and charcoal burning is commonly practiced in the Tchesamu forest, for example. Cutting of trees for firewood in the rainy season is another major threat to sustainable forest management.

Landscape Strategy

Community input from the village workshops informed the design of the COMDEKS Country Programme Landscape Strategy for Malawi. Table M-2 shows the five Landscape Outcomes agreed upon by communities, as well as the performance indicators that will be used to measure these outcomes.

Table M-2. Landscape Outcomes and Indicators from the Malawi Landscape Strategy

| Landscape Outcomes | Key Performance Indicators |

| Outcome 1:

Natural woodlands, Village Forest Areas and other habitats such as sacred groves, watersheds, and aquatic habitats are revitalized and conserved. |

· Hectares under afforestation/regeneration. · Number of nurseries, VFAs, and woodlots established. · Percent of seedlings surviving. · Number of groups involved in fish farming. · Number of fishing grounds rehabilitated or revitalized. |

| Outcome 2:

Sustainable agricultural practices implemented through adoption of agroforestry, crop diversification, conservation agriculture, value addition and processing of produce. |

· Number of hectares under sustainable land use. · Number of farm groups participating in crop diversification, agroforestry, or irrigated agriculture. |

| Outcome 3:

Community-based ecotourism developed to broaden household income base. |

· Number of people engaged in ecotourism as viable income-generating activity. · Number of community-based tourist centers constructed. · Number of tourists visiting the community- based tourist centers. |

| Outcome 4:

Community-based institutional governance structures in place for effective integration of conservation and production in the targeted landscape. |

· Number of CBOs created for integrated conservation. · Number of governance structures with existing bye-laws. · Number of Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs) and Forest Management Plans developed. · Number of COMDEKS lessons learned and best practices identified. |

| Outcome 5:

Diversified livelihood resources and improved welfare of the landscape. |

· Number of village loan and savings groups. · Number of group deposits/savings. · Number of loan agreements. |

To guide the choice of local projects, the Strategy calls for funding projects that:

- Promote initiatives for crop diversification, livestock production, bee keeping, agroforestry and the integration of crops and livestock.

- Improve the shelf life of an agricultural product, and increase value addition and processing of such crops as rice, cassava, mango and fish.

- Promote restoration and protection of riparian areas, wetlands, watersheds, and indigenous forests as well as the use of soil and water-saving technologies.

- Promote use of alternative materials (plastic or metals) for fabricating fish racks, shades, and mats in order to lower wood demand.

- Promote rearing of fish in ponds through capacity building and identification of suitable aquaculture sites.

- Establish and promote appropriate soil, water, and energy saving practices such as soil conservation, conservation agriculture, irrigated agriculture, water harvesting, and energy-saving technologies such as improved cook stoves.

- Build the leadership skills, group dynamics, and management capacity of local institutions such as CBOs, Village Natural Resource Management Committees, water management associations, fisheries associations, seed sharing networks and cooperatives.

- Improve access to credit and markets through development of appropriate business plans.

- Improve the provision of water and sanitation services to communities to improve local quality of life.

- Establish seed banks for developing disease-free planting material for economically important crops such as bananas and cassava.

A local development worker answers community questions, COMDEKS Malawi

Community-Led Landscape Projects

The COMDEKS Malawi Country Strategy currently has a portfolio of six local projects, supported by small grants of US$25,000 to $50,000 to six local CBOs and NGOs (see Table M-3):

Table M-3. COMDEKS Community-Led Projects in Takumbo-Kande Region, Malawi

| Project | Grantee (CBO/NGO) | Contribution to Landscape Resilience Outcomes | Description |

| Community-Based Ecotourism, Nature Conservation and Cultural Heritage Preservation Project | Myaya-Muuka CBO

US$50,000 |

Outcome 3 | Establish the basis for a local ecotourism industry through community training of tour guides, establishment of lodging and other tourism facilities, building nature trails, and documenting local cultural practices and sites. |

| Creating Sustainable Community Livelihoods Through an Integrated Approach | Chifundo-Chapeta CBO

US$25,000 |

Outcomes 1, 5 | Increase environmental awareness and establish its connection to increased income; build local business management skills; establish village saving and loan groups with proper regulations and begin loan disbursement for local enterprises; facilitate adoption of improved cookstoves; facilitate tree planting and natural regeneration in degraded areas. |

| Promotion of Environmental Education for Sustainable Development | Wildlife and Environmental Society of Malawi, Nkhata Bay Branch

US$30,000 |

Outcomes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Promote public awareness of the importance of sound environmental management and sustainable development; equip local people with skills to rehabilitate and sustainably manage essential ecosystems through their active participation. Equip women and youth with better skills for participation in environmental action. Establish an environmental education center to increase community access to environmental information. Foster partnerships for sustainable development between schools, CSOs, religious institutions, and others. |

| Improved Fish Processing and Sanitation | Nkhata Bay South Fishers Association

US$35,000 |

Outcomes 1, 4 | Promote fish farming as an alternative to capture fisheries. Pilot environmentally friendly fish drying racks to reduce deforestation. Improve sanitation at fish landing sites. Strengthen the Nkhata Bay South Fisher Association’s governance systems to enhance development of and compliance with byelaws. Promote alternative enterprises to enhance off-season financial security for fishers. |

| Mtowole-Chavula Beekeeping and Forest Conservation Project | Kuwirwi-Utoto Village Natural Resources Management Organization (KUTO)

US$25,000 |

Outcomes 1, 2 | Improve traditional bee-keeping practices and business skills to increase incomes from honey sales; increase sustainable use of area forests by reducing wood cutting, encouraging the adoption of improved cookstoves and other energy-efficient practices, controlling brush fires, planting trees, and encouraging natural regeneration of degraded areas. |

| Promotion of Sustainable Rural Livelihoods for Nature Conservation | Kunyanja Development Organization (KUDO)

US$50,000 |

Outcomes 1, 2, 5 | Promote crop diversification, seed improvement, planting of fruit trees, and establishment of small-scale irrigation to increase farm productivity and food security; improve agricultural practices to make more sustainable, including reducing use of chemical fertilizers; increase small livestock diversity, improve livestock management, and introduce dairying; facilitate forest tree planting and adoption of improved woodstoves to reduce forest degradation. |

Rice farming is largely practiced by women and children as men fish in the Lake, COMDEKS Malawi

“Each year we have been maintaining the fish racks using trees from the forest.

And when we heard about the COMDEKS project we were so happy and embraced it. The project will reduce the destruction of the forests and we are also saving money.”

–Magodi Nkhwazi, fisherman at the Tukombo fish landing site

Achievements and Impacts to Date

- Establishing the infrastructure and skills to support local ecotourism: Community workers have constructed three ecotourism chalets to accommodate visitors in three distinct sites representing the diversity of the local landscape. At the same time, 62 ha of indigenous forests proximate to the ecotourism sites have been brought under conservation management to keep the area desirable. To serve guests, 70 local youths have received training in community-based tour operation and guiding. In addition, nature trails to attractions such as hot springs, caves, streams, and unusually beautiful sites and overlooks have been charted. Ecotourism represents a new and potentially transformative economic opportunity in the target landscape, with the potential to increase incomes and provide economic incentives for better forest management.

- Increasing the diversity, productivity, and profitability of local agriculture: In the southern Nkhata Bay area, 75 households have received 210 goats in a “100% pass-on” scheme in which these recipient families will in turn distribute goats to other area families as their livestock increases, extending the benefit to some 600 households in three years. In the same area, 400 farmers have adopted more sustainable crop practices and have been provided with improved maize seed (open pollinated variety) and rice seed (aromatic variety), which is already bearing out in expanded production and higher incomes. In addition, 1300 fruit tree seedlings have been planted on area homesteads and 8,000 agroforestry seedlings have been planted in local fields. Some three tons of cassava seedlings have also been distributed to 100 area farmers, both for home consumption and for seed propagation.

- Establishing local fish-farming as a viable and sustainable alternative to traditional lake fishing: The first steps in creating a local nucleus of fish farming activities have been taken with the rehabilitation and stocking of 15 fish ponds, and the training of 20 fish farmers. An important innovation is the construction of 5 demonstration fish drying racks made with concrete pillars rather than wood in an attempt to provide an alternative to the forest destruction associated with construction of traditional wood drying racks. This has the potential to significantly reduce the environmental impact of not just fish farming, but traditional fishing. The region has 10 active fish landing sites, each containing hundreds of drying racks.

- Establishing saving and loan groups to empower local women and youth: At least 56 village saving and loan groups have been formed in the target landscape, with a combined membership of 690 people, of which 75 percent are women, 25 percent are youth, and only 2 percent are men. Small loans granted to community members are used to fund alternative livelihood activities that have displaced firewood selling and other unsustainable activities. The community-managed Village Saving and Loan Fund portfolio has grown rapidly to over US$18,000. One measure of the success of the Savings and Loan Clubs is that two commercial banks have now decided to offer mobile banking services in the area. Local savings and loan clubs also provide a venue for training in afforestation and business management, as well as discussions on gender, human rights, and group dynamics. Over 83 percent of households participating in the savings and loan clubs reported improved well-being, exemplified by such things as the ability to pay school fees for their children, pay for public transit, buy new clothes and bedding, or open a personal bank account. Some women also reported increased trust and respect from their husbands. Another benefit associated with the COMDEKS initiative and has attracted

- Strengthening protection of Village Forest Areas: Although there is a national policy requiring creation of Village Forest Areas (VFAs), it is typically not enforced. However, with the advent of the COMDEKS local projects, renewed interest has been shown by communities and traditional authorities in the area, resulting in the creation of 12 new VFAs, covering 34 ha. In fact, 3 Village Natural Resource Management Committees in the area have adopted policies mandating that all villages in their jurisdiction must demarcate VFAs. Such designation of VFAs strengthens local governance over forest resources.

Support to sustainable livelihoods brightens future of Malawi youth, COMDEKS Malawi

“With the additional US$250 grant we received from the project, we have set up a village bank. My husband and I are now business people. Our children’s school fees are paid on time and we have a happy family together. I can say here that my husband and I are on the same footing (50:50) when it comes to gender tasks. I am also respected by my husband. Isn’t this change?”

–Ida Mhone, a member of Mphatso Village Savings and Loan Group

Progress at the Landscape Level

The Malawi project portfolio addresses the need to reorient the area’s two major sources of livelihood—agricultural income from cassava and maize farming, and fishing income from Lake Malawi fisheries—to make them more sustainable, and also to relieve pressure on the area’s forests. Development of ecotourism as a viable alternative income source is an important piece of this effort as well. While there is great connectivity between these efforts, such as the connection between reforming fish drying practices and preserving area forests as attractive tourist areas, these project synergies have not yet had time to fully emerge.

Nonetheless, there is a sense of increasing cohesion among landscape communities, evidenced by greater landscape-level interaction between grantees and communities. One factor in this is the COMDEKS Project on promoting environmental education for sustainable development (EESD). This project is a landscape-wide initiative that works with all landscape grantees and communities, and it has helped to enhance the cooperation among various stakeholders. Through the EESD Project, a Landscape Environmental Education Centre has been established at Tukombo Trading Centre that will enhance learning for both communities and in-school and out-of-school youth. Strides in EESD will benefit other projects as well.

Another factor in building landscape-level connections is the financial empowerment initiative that works by creating village savings and loans groups. As a result of this initiative, communities are taking up more responsibilities, because now they believe that positive transformation is possible.

At the same time, two landscape level associations have recently been created: the Producers and Marketing Farmers’ Association, and the Nkhatabay South Beekeepers Association. Here, landscape-level umbrella committees are responsible for policy direction, while respective village-level clubs concentrate on ground activities. These activities are aimed at enhancing communities’ bargaining power with potential buyers, pooling their products together to access bigger and more dependable markets, and encouraging economies of scale.

One somewhat surprising area of progress at the landscape level can be found on the legislative side. As it happens, the target landscape lies within a single parliamentary constituency (Nkhatabay South), with one parliamentary (National Assembly) representative and two ward councilors. In the 20 May 2014 General Elections, Mrs Emily Phiri-Chinthu, Project Coordinator for Kunyanja Development Organization (a COMDEKS grantee with CBO oversight function) won the Nkhatabay South Parliamentary Seat on an independent ticket. Emily’s campaign manifesto was based on transforming the landscape through agriculture, women and youth empowerment, and enterprise development—a manifesto no doubt inspired by the COMDEKS philosophy. This will undoubtedly be a positive factor in strengthening landscape-level governance for ecosystem management, as well as women and youth empowerment.

In addition, the Constituency Development Fund, under the direct influence of the Parliamentary and Local Government representatives, could become an important source of support for infrastructure projects that directly contribute to the goals of COMDEKS projects. An example would be sanitation facilities on fish landing sites. Through Emily’s new role, there is also an opportunity for partnership building within and beyond the target landscape, which could result in the injection of additional resources into the landscape from other donors, both public and private.

Lessons Learned

- Landscape assessment can have repercussions beyond the immediate target landscape. For example, it may open up an area to potential outside interest groups as information about a hitherto unknown area begins to spread to other parts of the country. Before this exercise, little was known about this landscape except as just an ordinary stretch of land. Through the COMDEKS investment and publicity, other stakeholders such as investors and development practitioners are likely to come and take part in the development or exploitation of opportunities in the landscape.

- Landscape assessment must be approached with great sensitivity. First, many local residents fear that when people begin investigating the local landscape, it may be a prelude to alienation of their land. So this suspicion must be laid to rest by reassuring communities through the consultation process, explaining the goals and means of development projects at issue. In addition, organizers of the assessment should be aware of political differences among potential stakeholder participants and how this may affect their interactions. Finally, in introducing the COMDEKS program, organizers should be careful not to give the impression that project activities will solve all the community’s problems. Past experience with development projects that have overpromised has left communities disappointed.

- The participation of women and girls, and men and boys in the baseline assessment workshops was vital as it brought out their different needs in terms of choice of enterprises and conservation efforts to be supported. For example, tree planting was favored by women and girls, probably because it is women and girls that are overburdened with the responsibility of firewood collection.

- An analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the target area (a so-called SWOT analysis) is essential to begin the development of the Landscape Strategy. Ideally, this should be done using stakeholders from different disciplines and backgrounds so that local priorities and potential projects can be evaluated from different perspectives.

- The use of Village Savings and Loan clubs to fund livelihood activities involving nature conservation was new to this area and has been very successful. It is clear from local results that economic empowerment of this kind has reduced the dependence of local people—especially the poor—on natural resource extraction. It reinforces the insight that integrating wealth creation in conservation work creates win-win scenarios for both nature and its local custodians.

- Using the landscape approach to local conservation and development work provides an opportunity to deepen engagement with communities through sustained and concentrated effort. However, it also presents a challenge where community capacity for project planning and execution is low. Change agents must be prepared to invest more time and resources in order to achieve meaningful results and sustainable impacts.