Amakawa, N. 2004. “Income and Labor in Rural Villages of Cambodia – A Case Study of Rainy Season Rice Cropping in a Village in Kampong Speu Province”. Cambodia in a New Era, Research Library No. 539. Amakawa, N. ed. Institute of Developing Economies (IDE-JETRO), p.327-377.

Hori, M.; Ishikawa, S.; Kurokura, H.; Ponley, H., Somony, T.; Vuthy, L; Thuok, N. 2005. “Household Study of Small-scale Fisheries in Kompong Thom Province, Cambodia”. Materials developed by Tanji Research Team. http://mekong.job.affrc.go.jp/051111Tanjiteam. pdf .(accessed 2011-09-19), p.173-181.

Japan Wildlife Research Center. Community Fisheries of Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia. 2009. “Fiscal 2008 Report on Commissioned Projects for SATOYAMA Initiative”, p. 95-111. http://www.env.go.jp/nature/ satoyama/syuhourei/pdf/cwj_9.pdf. (accessed 2011- 09-19)

Kasai, T. 2003. Preliminary review on environmental preservation in the Tonle Sap Lake area, Cambodia. Ritsumeikan Journal of International Relations, 21, p.41-64. http://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/acd/ re/k-rsc/ras/04_publications/ria_ja/21_03.pdf. (accessed 2011-10-29)

Kobayashi, S. 2004. “Current Situation of Working and Making a Living in Villages in the Eastern Tonle Sap Region, Cambodia – A Case Study in Sankor District, Kampong Svay County, Kampong Thom Province”. Cambodia in a New Era, Research Library No. 539. Amakawa, N. ed. Institute of Developing Economies (IDE-JETRO), p.275-325

Kobayashi, S. 2007. Agricultural land right resolution process in post-Pol Pot rural Cambodia: a case study from the eastern Tonle Sap region. Asian and African Area Studies. 6-2, p.540-558. http://www.asafas. kyoto-u.ac.jp/publication/pdf/no_0602/540-558.pdf. (accessed 2011-10-31)

Nakahara, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Ajisaka, T. 1996. “Fisheries in the Tropics”. Tropical Agriculture. Watanabe, H.; Sakuraya, T.; Miyazaki, A. eds. Asakura Publishing Co., Ltd., p.146-157.

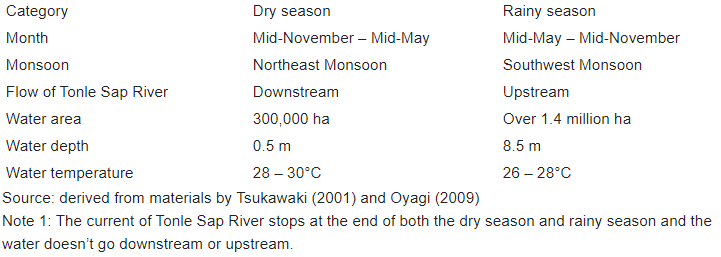

Oyagi, H.; Endo, S.; Okumura, Y.; Tsukawaki, S.; Mori, K. 2009. Characteristics of water temperatures in Lake Tonle Sap, Cambodia. Proceedings of the Institute of Natural Sciences, Nihon University. Geography, 44, p.167-176.

Tanikawa, S. 2001. “Sketch of a Village in Cambodia – Ruins and Residents”. Angkor Ruins and Sociocultural Development. Tsuboi, Y. ed. Rengo Shuppan, p.159- 196.

Tanikawa, S. 1997. Village of northwestern Cambodia 1: basic tesearch of socio-economics for North Srah Srang village. Journal of Sophia Asian studies. 15, p.219-258. http://repository.cc.sophia.ac.jp/dspace/ handle/123456789/5167. (accessed 2011-10-29)

Tsukawaki, S. 2001. “Angkor Ruins and Tonle Sap Lake”. Angkor Ruins and Sociocultural Development. Tsuboi, Y. ed. Rengo Shuppan, p.119-144.