An Integrated Seascape Approach to Revitalise Ecosystems and Livelihoods in Shimoni-Vanga, Kenya (SITR8-9)

20.03.2024

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

DATE OF SUBMISSION

19/09/2023

REGION

Africa

COUNTRY

Kenya

AUTHOR(S)

Tamara Tschentscher

Nancy Chege

Hugo Remaury

LINK

1 Introduction

Some of the world’s most valuable coastal and marine resources, such as mangrove forests, seagrass beds, coral reefs, and deltas, are found on the Kenya Coast and support local livelihood and economic activities. However, the coastal and marine environment faces numerous issues and challenges. High rates of population growth, urbanisation, expansion of industrial developments, overexploitation of natural resources, and climate change, are among the key drivers of environmental degradation in the coastal region (NEMA 2017).

Located in the southern coastal region of Kenya, the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape faces a myriad of challenges despite its significance for the biodiversity maintained within its diverse ecosystems—such as mangrove forests, seagrass beds, and coral reefs—which support coastal communities by sustaining livelihoods based on artisanal fishing and tourism.

An overarching problem facing the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape is environmental degradation due to weak community organisational capacity in collective decisionmaking and action in building and maintaining the resilience of this socio-ecological production landscape and seascape (SEPLS). Previous institutional support to counteract biodiversity loss was significantly weak,1 and where policies are appropriately targeted, e.g. in Community Managed Areas (CMAs), there is still low enforcement, as well as inadequate financial support and technical assistance. Although appropriate legal frameworks are in place, destructive methods of extraction and overexploitation of natural resources persist, particularly with regard to forests, mangroves, and fish populations. Destructive fishing and overexploitation of some fish species critical to ecosystem functioning, as well as unsustainable tourism practices, have particularly affected coral reefs and seagrass beds. Mangrove forests have faced additional threats from illegal logging and climate change.

Funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the community-based seascape management approach employed by the GEF Small Grants Programme (SGP) in Kenya aimed to restore ecosystem functions that form the basis of a mosaic of resource uses and enhance resilience of this socio-ecological production seascape. Three ecologically sensitive areas of global and national significance were selected for the implementation of this Sixth Operational Phase of the GEF SGP, one of which is the biodiversity-rich marine ecosystem of southern Kenya—the ShimoniVanga Seascape.

Through a participatory baseline assessment conducted in 2018, key stakeholders such as community members and leaders, civil society, academia, and national and county government agencies were engaged from the onset. They jointly identified key issues affecting the ecosystem and resource degradation, assessed capacities and needs, as well as determined priorities for community conservation actions.

Through partnerships with a multitude of stakeholders that ensured different interests were addressed and common conservation goals were pursued, the supported initiatives jointly contributed to revitalising this critical socio-ecological production seascape. Between 2018 and 2022, activities promoted mangrove forest and coral reef rehabilitation, eco-tourism enterprise development, sustainable fisheries and fish processing value chain development, and improved waste management systems. They have further contributed to strengthening multi-stakeholder collaboration, the capacities of Beach Management Units (BMUs), and improved monitoring, control, and surveillance of Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMAs). Coral reef regeneration initiatives have piloted innovative restoration methods to support the healthy functioning of reef ecosystems, studying their strengths and weaknesses to determine the most community-accessible and effective models for scaling up and replication. These community-based initiatives are vital to creating a “society in harmony with nature” and conserving the rich local marine and terrestrial biodiversity (GEF SGP Kenya et al. 2018). This case study showcases these activities and documents knowledge and best practices that build the resilience of SEPLS by developing and diversifying livelihoods while enhancing biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services.

1 Poaching is driven by poverty and the accessibility of lucrative illegal markets. While Kenya is a signatory to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) that bans trade in protected species, inadequate collaboration by law enforcement institutions poses a substantial challenge in enforcement of anti-poaching laws (NEMA 2017).

2 The Seascape

2.1 Geography

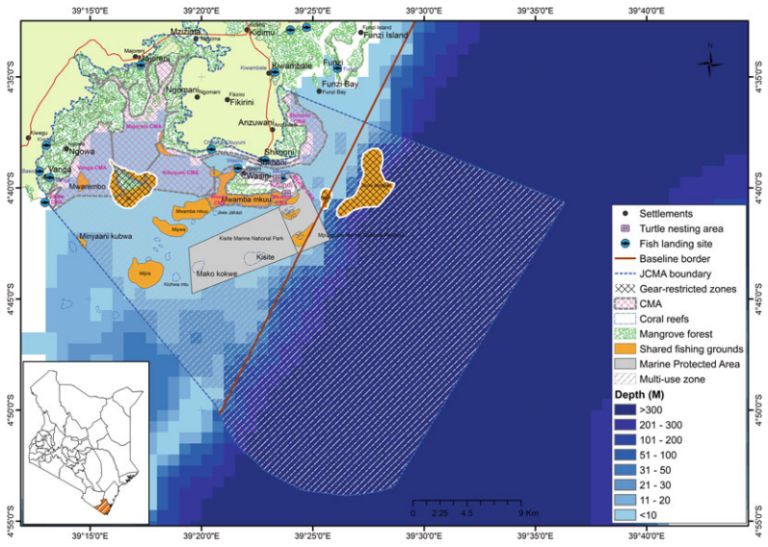

Located in Kwale County in the southern coastal region of Kenya, the ShimoniVanga Seascape covers an area of 860 km2 (see Fig. 10.1; Table 10.1). Forming part of the transboundary Msambweni-Tanga seascape, it shares its northern Shimoni boundary with Msambweni (Funzi Bay) and its southern Vanga boundary with Tanzania. Seven villages are located along the seascape: Shimoni, Majoreni, Vanga, Jimbo, Kibuyuni, Wasini, and Mkwiro. The people of these villages largely depend on the seascape for their livelihoods. The latter two villages are located on Wasini Island, just off the coast from Shimoni village. Apart from Wasini Island, the seascape comprises the uninhabited Mpunguti ya juu, Mpunguti ya Chini, Mako Kokwe, and Sii coral islets (GEF SGP Kenya et al. 2018).

2.2 Biological Resources and Land Use

The seascape is rich in floral and faunal biodiversity, particularly corals, mangroves, and seagrasses, as well as a variety of marine mammals, crustaceans (shrimps, lobsters, and crabs), pelagic and demersal fishes, cephalopods (octopus, squids, and cuttlefish) and echinoderms (e.g. sea cucumbers), birds, and reptiles. Sandy beaches and estuaries are also found in the area with one permanent river (Ramisi) draining into the ocean. The importance of the seascape is underscored by a Marine Protected Area (MPA), situated within the Kisite-Mpunguti Marine National Park and Reserve, that demonstrates the highest coral diversity of Kenya’s MPAs, with 203 species and a 50% coral cover (Obura 2012).

Such seascape ecosystems are highly interconnected, with coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass beds depending on each other’s health to maintain their sensitive ecosystem balance. Local people depend on this seascape for fishing, tourism activities, mangrove harvesting, and seaweed farming. Arable land with moderate rainfall and warm weather form ideal conditions for agricultural production in the area. Livestock rearing is also practiced in the hinterland of the area.

2.3 Socio-Economic Context

The majority of the 18,000 people living within the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape depend mainly on fishing, farming, tourism, and trade for their livelihoods (GEF SGP Kenya et al. 2018). Some villages are home to marginalised and indigenous groups of Wakifundi and Wachwaka, as well as Makonde migrants from Mozambique.

Fishing is the predominant livelihood activity in all the villages, with nearly 100% of the population in Mkwiro village dependent on fishing, followed by fish trading (25%) (KCDP 2016a). Cash crop farming accounts for 22% of household incomes, while livestock production contributes 18% (GEF SGP Kenya et al. 2018). There have also been attempts to develop small-scale fish processing, particularly in Kibuyuni, Majoreni, and Shimoni. Tourism services such as boat tours and mangrove boardwalks help diversify livelihoods in the area.

About 2632 fishers are active in the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape. Migrant fishers, who are mostly found in Vanga and Jimbo, make up about 15% of local fishers (GEF SGP Kenya et al. 2018). Multiple fish species can be sourced with various types of gear, but illegal fishing gear such as spear guns and beach seines are frequently spotted. Fisherwomen only make up about 3% of total fishers and are mainly found in Kibuyuni, Mkwiro, and Wasini (see Fig. 10.2 for a map of Wasini Island). However, women are particularly active further along the fish value chain, particularly in processing and selling fish at the village level.

3 Challenges and Opportunities

3.1 Environmental and Social Challenges

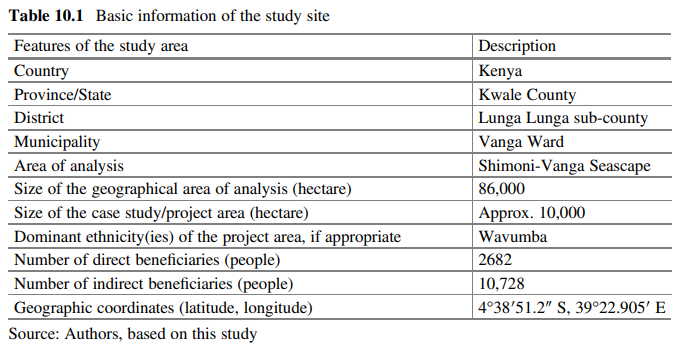

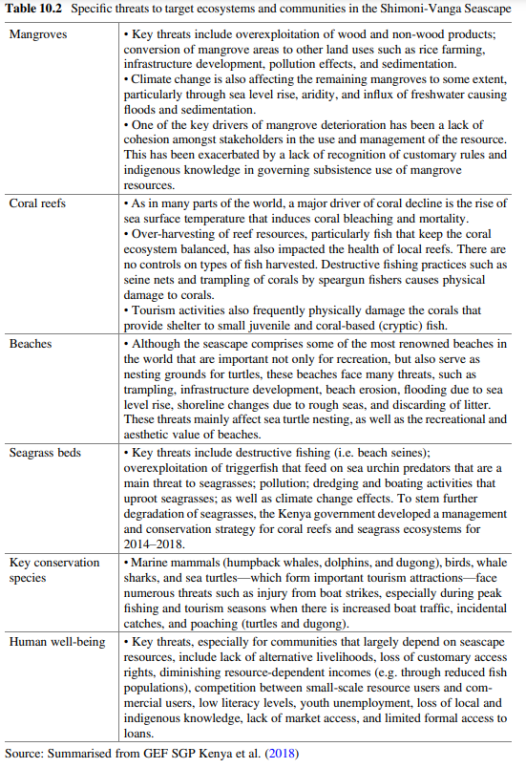

To determine a comprehensive baseline and jointly set intervention priorities for SGP-supported, community-led initiatives with seascape stakeholders, existing key challenges and opportunities were assessed through extensive community consultations and a baseline assessment conducted in 2018. This process is explained in further detail in the next section. Table 10.2 summarises specific threats to target ecosystems and communities in the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape, as determined during these discussions (GEF SGP Kenya et al. 2018).

3.2 Opportunities for Ecosystem Conservation and Livelihood Development

One approach to improve the effectiveness of fisheries management in Kenya is the direct supervision of joint fisheries co-management areas (CMAs) and related management plans by local communities, notably Beach Management Units (BMUs) and county authorities (MALF 2017).2 This type of arrangement is rooted in the legal framework of the Fisheries Management and Development Act No. 35 of 2016 as well as the 2007 Fisheries BMU Regulations. For long-term sustainability, this co-management system adopts an ecosystem approach to fisheries (EAF).

2 The Government of the Republic of Kenya is composed of 47 counties, and each county has its own semiautonomous government.

Since Kenya adopted an EAF framework in 2011, several area-, species-, and gear-based management plans have been developed using this approach (Garcia et al. 2003).3 These include the Lobster Fishery Management Plan, Small-Scale Purse Seine Fishery Management Plan, and Marine Aquarium Fisheries Management Plan.

In Shimoni-Vanga, seven BMUs, each representing one seascape community, jointly co-manage the CMA seascape to promote ecosystem conservation, optimise social and economic benefits for local communities, and improve governance and management of the seascape. This includes ensuring compliance with local and national resource use regulations, as well as approval of fishing vessel registrations and fishing licenses (Fig. 10.3 shows a local fishing boat).

The 5-year Joint Co-management Area Plan (JCMAP) (2017–2021) included seven village-based Co-management Area Plans (CMAPs) that complemented the Kisite-Mpunguti Marine Protected Area Management Plan (2015–2025) (GEF SGP Kenya et al. 2018; KCDP 2016b). However, the managing BMUs struggled with insufficient capacity to effectively conduct Monitoring, Control, and Surveillance (MCS), which, coupled with poor inter-agency collaboration and governance, has resulted in weak enforcement. Despite these weaknesses, this communitymanagement framework represents a promising foundation to further build the socio-economic resilience of this production seascape with global significance (COMRED and Naturecom Group 2020b).

3 The EAF was adopted by the FAO Committee on Fisheries (COFI) in response to the need to implement sustainable development principles, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (FAO 1995).

4 Activities, Achievements, and Impacts

Collective action by the various stakeholders to strengthen socio-ecological resilience for the sustainable use and management of coastal marine resources is key to broad acceptance of the outcomes of collective action and achieving sustainable benefits for humans and ecosystems (COMRED and Naturecom Group 2021). Emphasis on support from various actors to community organisations for development and implementation of adaptive management projects reinforces the positive results of the collaborative efforts. Based on this understanding and building on the joint CMA approach to resource management, the GEF Small Grants Programme (SGP) in Kenya employed a highly participatory, community-based seascape management approach as its core programming framework for its 6th Operational Phase (OP6). To ensure various actors and stakeholders were closely engaged in the design, implementation, documentation, and monitoring of activities, GEF SGP Kenya worked with a broad spectrum of stakeholders across government, civil society, the private sector, and academia.

4.1 The Seascape Approach

As identified during consultations with key stakeholders within the baseline assessment conducted in 2018 by the GEF SGP, an overarching challenge in achieving sustainable use and management of coastal marine resources and other related natural resource systems has been the lack of a coordinated approach to harness the connectivity of the ecosystems. A segregated approach can result in an intervention in which one component is beneficial to certain ecosystem segments but detrimental to others, which can cause conflicts of interest for different groups (COMRED and Naturecom Group 2021).

The seascape approach in Shimoni-Vanga aimed to address a mosaic of seascape resource uses in a holistic manner. Management of such a mosaic seascape with resources that are highly interconnected required an integrated approach that facilitated and promoted interaction among resource users. The seascape approach encouraged cross-community interactions and synergies among community projects, enabling harmonisation of activities to optimise protection, manage tradeoffs, and ensure sustainability.

4.2 Stakeholder Engagement and Use of Resilience

Indicators

Local communities have a great interest in ensuring the long-term resilience of their SEPLS in general, particularly when the majority of the local population depends on ecosystem services from landscape or seascape for their livelihoods. They also often hold the key to unlocking the most suitable solutions by coupling traditional knowledge with modern best practices when given the chance to participate. Starting with a participatory baseline assessment applying the Indicators of Resilience in SEPLS (Bergamini et al. 2014), community members involved in environmental conservation in the seascape were directly engaged from the onset. Community members and leaders from seven villages within the Shimoni–Vanga seascape, along with four community-based organisations representing both men and women in each village, and representatives from government agencies, the private sector, and local NGOs participated in the baseline assessment in 2018. This process ensured joint identification of: resources within the seascape, their socio-ecological resilience, and key issues affecting their management, as well as

community conservation priorities and proposed actions.

The Coastal and Marine Resource Development (COMRED) and Naturecom Group was identified as a strategic partner to oversee the baseline assessment, as well as to engage in development and implementation of the seascape strategy. Since its establishment in 2006, this non-profit organisation has promoted practical solutions to problems faced by coastal and marine environments and communities in achieving sustainable development. COMRED was also one of the key consultants engaged by the national government to develop the Joint Co-Management Area Plan for the Shimoni-Vanga seascape.

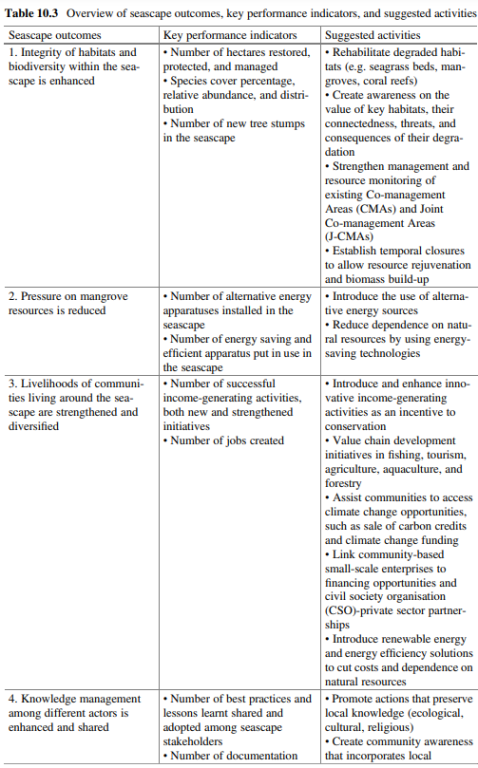

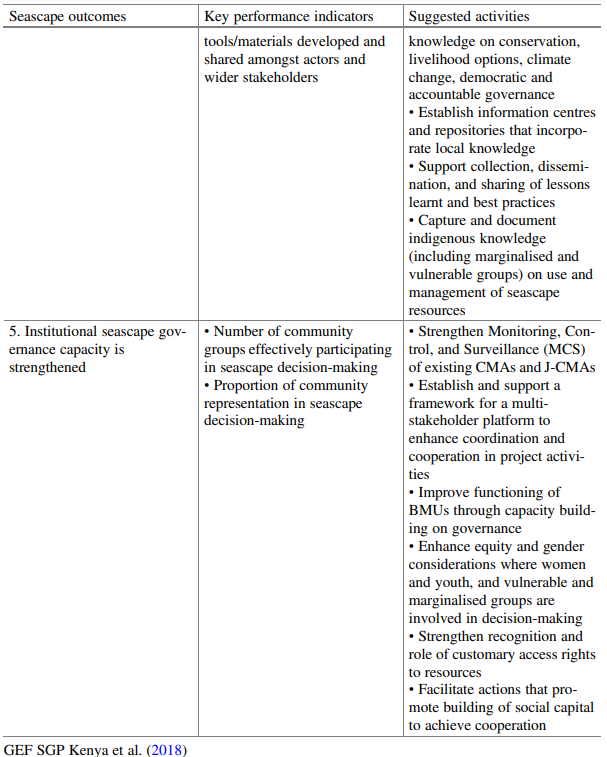

4.3 Seascape Strategy and Community-Led Landscape Projects

The baseline assessment and community consultations gave rise to the ShimoniVanga Seascape Strategy, which set out five landscape outcomes and associated indicators to measure progress towards these outcomes (see Table 10.3 for an overview of Seascape Outcomes, Key Performance Indicators and suggested activities jointly determined by stakeholders and outlined in the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape Strategy). The strategy formed a key element of the seascape planning process, where seascape communities generated a shared vision of what a more resilient local seascape would look like and determined what actions would be required to realise this vision (UNDP 2016).

4.4 Achievements and Impacts to Date

Based on this seascape strategy and the roadmap for the selection of project proposals, 16 community-led initiatives were competitively selected and received financial and technical support from GEF SGP Kenya to contribute towards improved resource management, livelihood development, and ecosystem restoration (COMRED and Naturecom Group 2020b). Activities implemented based on an integrated approach included: capacity building for improved Monitoring, Control, and Surveillance (MCS), particularly of the Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMAs)4 ; expansion and demarcation of LMMAs; mangrove planting and coral reef rehabilitation; eco-tourism enterprise improvements; fish value addition and post-harvest handling; waste management and value addition; and education and awareness through art and performance (UNDP 2021).

Key achievements are highlighted as follows:

Environmental Awareness Harnessing the Kenyan enthusiasm for music and arts, the Mchongo youth group has been successfully using dance, theatre, poetry, and songs to entertain, but essentially to educate and create awareness among local communities on a variety of topics. Through SGP support, this group was able to acquire technical equipment to improve their communication products. Gaining wide recognition among communities was instrumental for the group in communicating messages on conservation through art, networking, and YouTube videos aimed at raising awareness on the importance of personal responsibility for care of the environment (UNDP 2021).

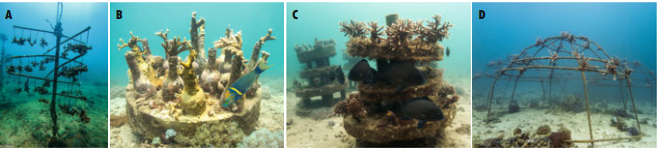

Coral Reef Rehabilitation The Wasini and Mkwiro BMUs piloted innovative coral reef restoration projects that are accelerating the slow, natural recovery of reefs. With close engagement of local communities, projects worked to enhance reef structure through artificial reef constructions onto which coral fragments grown in nurseries were transplanted (see Figs. 10.4 and 10.5). In Mkwiro, a project collected 30 species of common branching coral genera, which were multiplied over 2 years between August 2019 and August 2021 until the nursery contained 10,000 fragments. Since then, fragments can be harvested on an annual basis. Between 2019 and 2021, about 3000 coral fragments were placed on 750 artificial reef structures each year. In Wasini, 8300 coral fragments were raised in mid-water table nurseries for 6–8 months following a coral gardening concept before being transplanted on denuded reef substrates or on artificial reef structures (see Fig. 10.6). Materials used for nursery fixtures and artificial reef modules were locally sourced. These coral restoration sites have brought significant benefits to local communities. Ecological benefits include healthy reefs that have become fish aggregation and breeding zones, leading to recovery of fish populations. Activities further generated employment opportunities, including those for 35 community members engaging in coral restoration activities and 11 trained and employed reef rangers. Fish spillover from aggregation zones has benefitted local subsistence fishers. Apart from increased fisheries income, local tourism is benefitting as the healthy reef sites and restored fish populations attract divers and snorkelers. There have already been turtle sightings that had not occurred in years. Finally, these initiatives have considerably contributed to increased awareness and community conservation stewardship, generating vital research data and lessons for successful coral restoration projects and enhancing community ownership and partnerships among key stakeholders (REEFolution Foundation et al. 2021).

4 An LMMA is an area of nearshore waters and coastal resources that is largely or wholly managed at a local level by the coastal communities, land-owning groups, partner organisations, and/or collaborative government representatives who reside or are based in the immediate area.

Mangrove Restoration Kenya Forest Service (KFS), a government agency, took a leading role in advising local communities on mangrove nursery establishment and mangrove planting. Over 6300 mangrove seedlings were planted by the Majoreni Beach Management Unit (BMU), Jimbo BMU, and the Wasini Women Group. These have contributed considerably to improving fisheries production as well as carbon capture and coastal protection (see Fig. 10.7). Regular monitoring of replanted mangroves was undertaken in areas where there is a functional Participatory Forest Management Plan (PFMP) and a Management Agreement (MA) developed between the community and KFS. The PFMPs and MAs require the community and partners to identify areas in need of replanting, undertake replanting, and conduct regular monitoring of replanted areas. So far, replanted mangroves have shown a 50% survival rate. These activities have created 110 casual jobs for local communities in mangrove nursery establishment, operation, and on mangrove seedling plantations for mangrove forest restoration (UNDP 2021).

Fish Value Chain Addition Many women in coastal Kenya make a living as fish merchants and have done so for a long time. However, incomes have remained low. To improve the capacities and livelihoods of these still marginalised women, the community-based organisation Indian Ocean Water Body (IOWB) led activities with four BMUs in Mkwiro, Shimoni, Vanga, and Jimbo. IOWB provided capacity-building training on fishing quality control (handling), value addition, marketing, sales, and entrepreneurship development to 112 women. It also supported women in the purchase of equipment such as cooling boxes, freezers, and weighing scales to further improve their distribution and sales and helped upgrade Pwani Fish Marketing’s fish processing facility. With the resulting increased incomes and enhanced financial independence through fish trade, the women have noted a higher level of pride and satisfaction (UNDP 2021).

Waste Management The Center for Justice and Development (CEJAD)—a national non-governmental organisation (NGO) and GEF SGP grantee partner— partnered with the communities of Mwkiro and Wasini through the Mkwiro Eco-friendly Conservation Group and Wasini Women Group to raise awareness on the threat of marine plastic pollution, organise beach clean-ups, and promote locally suitable waste recycling mechanisms that support sustainable livelihoods. They purchased solid waste bins and established a demonstration centre for recycling solutions. Following the philosophy “taka ni mali” (“waste is money”), CEJAD facilitated the training of 40 community members, 30 of them women, and provided equipment and tools to turn plastic waste into sellable artefacts such as key holders, mats and hats, and bracelets (see Figs. 10.8 and 10.9). These have been exhibited and offered for sale at the demonstration centre. Through installation of a waste baling machine and a partnership with a private sector company to recycle plastic, further employment opportunities have been created for waste collection, sorting, cleaning, baling, transportation to recyclers, and facility security. The baler

has been a game changer as it tremendously cuts costs for waste processing and transportation. Increased awareness on pollution impacts coupled with employment and income generation opportunities have led to broad community support for these initiatives. Local communities have celebrated World Oceans Day, conducting beach clean-ups with grantee partners. To further improve waste management governance in the long term, the Wasini Women Group established a community waste management committee that developed rules on waste management to reduce pollution, and CEJAD contributed to a solid waste management policy for the county government of Kwale (UNDP 2021).

Eco-tourism Development Shimoni has a rich, historical past, albeit a sad one. At the height of the slave trade in the 1750s, it was a bustling town as a slave-holding port for East Africa’s slave trade. The holding pens were the naturally existing caves, which today are tourist attractions. The local community in partnership with the National Museums of Kenya enhanced tourism infrastructure by installing solar lights in the caves, establishing a nature trail in the nearby Shimoni forest, and erecting a viewing platform next to the caves. With the newly repaired road, and the impending construction of a fishing port in Shimoni, tourism traffic is bound to grow. Additionally, Wasini and Mkwiro community members were trained as dive guides to offer tours to give visitors chances to see the growing number of fish species resulting from the successful coral rehabilitation activities, as well as improved management of the locally managed marine area. Through a partnership between the local boat owners association and Kenya Wildlife Service, community members can now offer boat tours to Kisite-Mpunguti Marine National Park, which is known for its dolphin sightings.

CMA Management Capacities Under the leadership of the Kenya Fisheries Service and the Fisheries Department of Kwale County Government, NGO partners conducted trainings in MCS tools and processes to strengthen enforcement capacities of BMUs. In August and September 2020, 76 executive and patrol sub-committee members of the BMUs (including 24 women) received theoretical and practical training in pre-patrol, patrol, and post-patrol procedures, fish catch data collection and monitoring, fish handling and quality assurance, documentation and reporting practices, and patrol planning logistics. The trainings were led by officers from Kenya Fisheries Service, Kwale County Fisheries Department, Kenya Coast Guard Service, Kenya Wildlife Service and Kenya Forest Service, with support from COMRED as a lead strategic partner. As a result of these trainings, BMUs reported an increased number of licensed fishers and registered fishing crafts—for example, 190 fishers licensed in Vanga in 2020 compared to 166 in 2019, and 60 registered fishing boats in 2020 compared to 41 in 2019 (see Fig. 10.10 for a local canoe in operation). The Kibuyuni BMU reported 105 fisher licenses in 2020, a significant increase from 29 in 2019 (COMRED and Naturecom Group 2020b). Additionally, enforcement of BMU by-laws has been improved. By-laws ban fishing in certain zones during spawning seasons and stipulate fishing net mesh sizes to ensure that only mature fish are caught, for example. This is to some extent a return to more traditional practices.

Participatory Governance One of GEF SGP Kenya’s major targets during this operational phase was to establish a multi-stakeholder platform to foster long-term working relationships and create a shared vision among seascape stakeholders with respect to coastal and marine resource use, management, and development. This multi-stakeholder forum for the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape was established with support from COMRED and Naturecom Group as strategic partners, as well as the Government of Kenya and County Government of Kwale (COMRED and Naturecom Group 2020a). It was officially inaugurated in January 2020, co-chaired by the Ministry of Interior and Coordination of the national government (Office of Deputy County Commissioner, Lunga Lunga sub-county) and the County Government of Kwale (Sub-county administrator, Lunga Lunga sub-county). Membership in the multi-stakeholder platform is based on the area of residence and interest in the seascape. Members include: (i) statutory agencies such as Kenya Wildlife Service, Kenya Fisheries Service, National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), and statutory community-level agencies, such as Beach Management Units (BMUs) and Community Forest Associations (CFAs); (ii) non-state actors—NGOs, CBOs, and the private sector, and (iii) observers—parties who may have an interest in the seascape (COMRED and Naturecom Group 2021).

5 Discussion

5.1 Key Innovations for Replication

The active coral reef restoration projects led by the Wasini and Mkwiro BMUs, piloting innovative methods and techniques, have generated remarkable results and impacts. Partnering with the REEFolution Foundation as well as Wageningen University and Research, the Coastal Oceans Research and Development—Indian Ocean (CORDIO) East Africa, and the Kenya Marine Fisheries and Research Institute (KMFRI), the BMUs and COMRED piloted and evaluated different coral fragment nursery types, artificial reef structures, and gardening techniques as mentioned earlier. Although these methods have been tested before in other contexts,5 the strengths and weaknesses of different techniques had not yet been compared and documented. At both project sites, SGP-supported projects tested different coral species for nurseries and transplantation, monitoring their growth and survival rates with different stressors (such as bleaching events) over time and artificial reef construction types (see Fig. 10.11 for examples of coral fragments’ growth). This data was recorded to identify the most resilient species and most suitable growing and transplantation methods. One of the key conclusions by the Mkwiro BMU highlighted that the coral-tree design is the most cost-effective nursery technique, where a full-grown coral fragment can be reared for about US$0.33 per fragment, including costs of nursery construction, diving costs, maintenance, and labour.6 Monitoring will continue with assessments of long-term and ecologically significant changes in coral cover and fish populations on a biannual basis. The invaluable knowledge and lessons generated from these initiatives will aid decisions on the most feasible and successful coral reef restoration techniques for future communitybased initiatives (REEFolution Foundation et al. 2021).

5 Coral reef restoration is a relatively new approach to reef restoration both in Kenya and in the region. However, currently, a number of initiatives in reef restoration using similar approaches are being undertaken in other coastal areas in Kenya, such as Kuruwitu (Kilifi), Pate (Lamu), and Diani (Kwale). One of the most successful reef restoration initiatives is on Cousin Island, Seychelles, while other reef restorations are currently being undertaken in Tanzania and Mozambique.

6 The costs for the other artificial reef structures were as follows: $15.21 per Bottle Reef Unit (BRU), $43.78 per Cake and $59.12 per Cage (including welding costs).

5.2 Progress at the Seascape Level

The establishment of the multi-stakeholder platform has been an important milestone in ensuring engagement of communities and the various local stakeholders of the coastal and marine resources in any related decision-making processes. It enhanced effective and collective decision-making and strengthened the conservation and management of natural resources by aligning and coordinating activities. This platform also helped by informing stakeholders on implementation of government plans and initiatives and ensuring that the voices and needs of different interest groups informed joint decisions for shared benefits. By incorporating and aligning new initiatives and strategies to existing government plans, coordination, and crosssectoral synergies can be enhanced (COMRED and Naturecom Group 2020a). Committees for different thematic areas are in the process of being established as part of the forum, including those on research, security and surveillance, livelihoods and community, management, fundraising, and cross-cutting areas such as gender and health.

On 9 December 2021, the Kisite-Mpunguti Marine National Park and Reserve, located within the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape, made history as Kenya’s first Blue Park. It was awarded the gold-level Blue Park Award by the Marine Conservation Institute for achieving the highest standards for marine life protection and management. The Blue Park Award recognises outstanding efforts by nations, MPA managers, and local community members to effectively protect marine ecosystems now and into the future. There are only 21 Blue Parks around the world, designed to protect and regenerate ocean biodiversity.

5.3 Lessons Learned and Moving Forward

The MCS trainings also involved discussion of challenges and lessons learned, as well as identification of needs and a way forward. Analyses and discussions highlighted that Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing has predominated Shimoni-Vanga’s small fisheries industry. Reasons include lack of awareness and ignorance of fisherfolks regarding laws and regulations. There is also insufficient understanding that unsustainable practices will affect the very resources that the fisherfolk harvest and depend on. Initiatives will need to build on early efforts to sensitise local communities concerning impacts on their livelihoods and support income generation by value chain addition activities and other alternative livelihood opportunities.

Key lessons and recommendations include the need for regular follow-up and support in implementation and monitoring of progress and translation of training modules to Swahili, which is better understood by most BMU members. Discussions also highlighted that support from and engagement of different stakeholders, including the national and county government as well as civil society actors, is essential to further improve BMU operations (COMRED and Naturecom Group 2020b).

Moving forward, the possibility of joint patrols among all the Shimoni-Vanga BMUs and the engagement of enforcement agencies, e.g. Fisheries and Kenya Coast Guard, to improve the effectiveness of this mechanism is being explored among stakeholders. Also, integrity trainings and protocols are being elaborated to avoid leakage of patrol information. Furthermore, initiatives will promote clear demarcations of designated fishing areas.

To further reduce illegal fishing practices, county government support to communities for acquisition of sufficient adequate fishing gear will be needed. Fish merchants also need to be further sensitised on avoidance of purchasing undersized fish and fish species that are not for human consumption. BMUs have already discussed and stand ready to support the identification and development of locally suitable income-generating activities for improved local livelihoods and further support of MCS activities in the seascape (COMRED and Naturecom Group 2020b).

6 Conclusion

Over a period of three and a half years from mid-2018 to early 2022, the Small Grants Programme, implemented by UNDP, provided technical assistance and financial support from the GEF to 16 local organisations to build the social, economic, and ecological resilience of the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape. An integrated, community-based seascape approach was taken to engage local communities and other key stakeholders in the seascape in a highly participatory seascape planning process. This allowed for the development and implementation of adaptive management projects in ways that ensured that benefits, priorities, and activities, for both the global environmental agenda and local sustainable development, were effectively aligned with the different interests of seascape resource users. The wide range of activities were designed to complement each other and generate synergistic results at the seascape level, promoting marine and coastal biodiversity conservation, as well as building organisational and governance capacity for enhanced financial and institutional sustainability. Despite this short implementation period, promising results have already been recorded. Although there is still much that can and needs to be done, the implementation of this integrated seascape approach that emphasises community priorities have demonstrated that ecosystem restoration and livelihoods can be effectively revitalised.

References

Bergamini N, Dunbar W, Eyzaguirre P, Ichikawa K, Matsumoto I, Mijatovic D, Morimoto Y, Remple N, Salvemini D, Suzuki W, Vernooy R (2014) Toolkit for the indicators of resilience in socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes. UNU-IAS, Biodiversity International, IGES, UNDP, Rome

Coastal and Marine Resource Development (COMRED) & Naturecom Group (2021) Innovations for a sustainable ocean: the Shimoni-Vanga multi-stakeholder’s forum—promoting social impact and sustainable management of the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape. COMRED, Mombasa

Coastal and Marine Resource Development (COMRED), Naturecom Group (2020a) Memorandum for the establishment of the Shimoni-Vanga Seascape multi-stakeholders forum. COMRED, Mombasa

Coastal and Marine Resource Development (COMRED), Naturecom Group (2020b) MCS training report for the Shimoni-Vanga BMUs. COMRED, Mombasa

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (1995) Code of conduct for responsible fisheries. FAO, Rome

Garcia SM, Zerbi A, Aliaume C, Do Chi T, Lasserre G (2003) The ecosystem approach to fisheries. Issues, terminology, principles, institutional foundations, implementation and outlook. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Fisheries Technical Paper, No 443, Rome

GEF SGP Kenya, Coastal and Marine Resource Development (COMRED), Naturecom Group (2018) Seascape strategy for building social, economic, and ecological resilience—ShimoniVanga Seascape.

GEF SGP Kenya, Nairobi Kenya Coastal Development Project (KCDP) (2016a) Fisheries and socio-economic assessment of Shimoni-Vanga area. Baseline report. Kenya South Coast, KCDP

Kenya Coastal Development Project (KCDP) (2016b) Ecological risk assessment for the development of a Joint Co-Management Area (JCMA) plan in the Shimoni-Vanga Area, South Coast Kenya. State Department for Fisheries and Blue Economy report. KCDP, Kenya South Coast

Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries (MALF) (2017) The Shimoni-Vanga Joint Fisheries Co-Management Area Plan (JCMAP): a five-year co-management plan to guide the development of Shimoni-Vanga joint fisheries co-management area. MALF, Government of Kenya, Kwale County

National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) (2017) State of the coast report II: enhancing integrated management of coastal and marine resources in Kenya. NEMA, Government of Kenya, Nairobi

Obura D (2012) The diversity and biogeography of Western Indian Ocean reef-building corals. PLoS One 7(9):e45013

REEFolution Foundation, Wageningen University and Research (WUR), Coastal Oceans Research and Development—Indian Ocean (CORDIO) East Africa, Coastal and Marine Resource Development (COMRED), Kenya Marine Fisheries and Research Institute (KMFRI), Mkwiro Beach Management Unit (BMU), Wasini Beach Management Unit (BMU) (2021) Coral reef rehabilitation in Shimoni-Vanga Seascape: a case study of Mkwiro and Wasini LMMAs—developing community-accessible rehabilitation methods on degraded reefs. REEFolution Foundation, Oosterbeek

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2016) A community-based approach to resilient and sustainable landscapes: lessons from phase II of the COMDEKS programme. UNDP, New York

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2021) Project implementation report (PIR) 2021, sixth operational phase of the GEF SGP in Kenya. UNDP, New York

Note

The opinions expressed in this chapter are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNU-IAS, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent.

Open Access This chapter is licenced under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ igo/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to UNU-IAS, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. If you remix, transform, or build upon this book or a part thereof, you must distribute your contributions under the same licence as the original. The use of the UNU-IAS name and logo, shall be subject to a separate written licence agreement between UNU-IAS and the user and is not authorised as part of this CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO licence. Note that the link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the licence.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from

the copyright holder.