A New Paradigm for Land Development: Creating Circular Economy Villages within a Distributed & Networked Global City

18.12.2019

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION

-

PolisPlan

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION

-

18/12/2019

-

REGION

-

Oceania

-

COUNTRY

-

Australia

-

KEYWORD

-

Regenerative agriculture, Distributed network; Circular Economy, Co-living, Zero Waste

-

AUTHOR

-

Steven Liaros (Sydney University, PolisPlan) & Nilmini De Silva (PolisPlan)

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

2. PROPONENTS

PolisPlan is a strategic town planning and engineering consultancy. The directors of PolisPlan, Steven Liaros and Nilmini de Silva, have decades of local government experience and are now applying that experience to create a new model for land development that is economically affordable and efficient, socially resilient and connected as well as being environmentally sustainable. Steven and Nilmini also bring to this project their skills in town planning, water management, community consultation and project management. Their local government experience is in a variety of roles, including local infrastructure planning, preparation of development control plans, planning instrument amendments, natural systems management and working with multi-disciplinary teams to deliver complex projects.

3. DEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL

The project proponents seek to advance the development of a new model for regenerative land development that integrates regenerative agriculture with the built environment.

-

3.1. BACKGROUND TO THE DEVELOPMENT MODEL

-

The development model is underpinned by several years of research by the report authors. The model is based on the principles of the Circular Economy—systems thinking, planning for life cycles and striving for zero waste. The model is also the subject of a PhD project by Steven Liaros at The University of Sydney’s Department of Political Economy— ‘A New Paradigm for Land Development: Creating Regenerative Nodes within a Distributed & Networked Global City’. The regenerative nodes are described as ‘Circular Economy Innovation Hubs’.

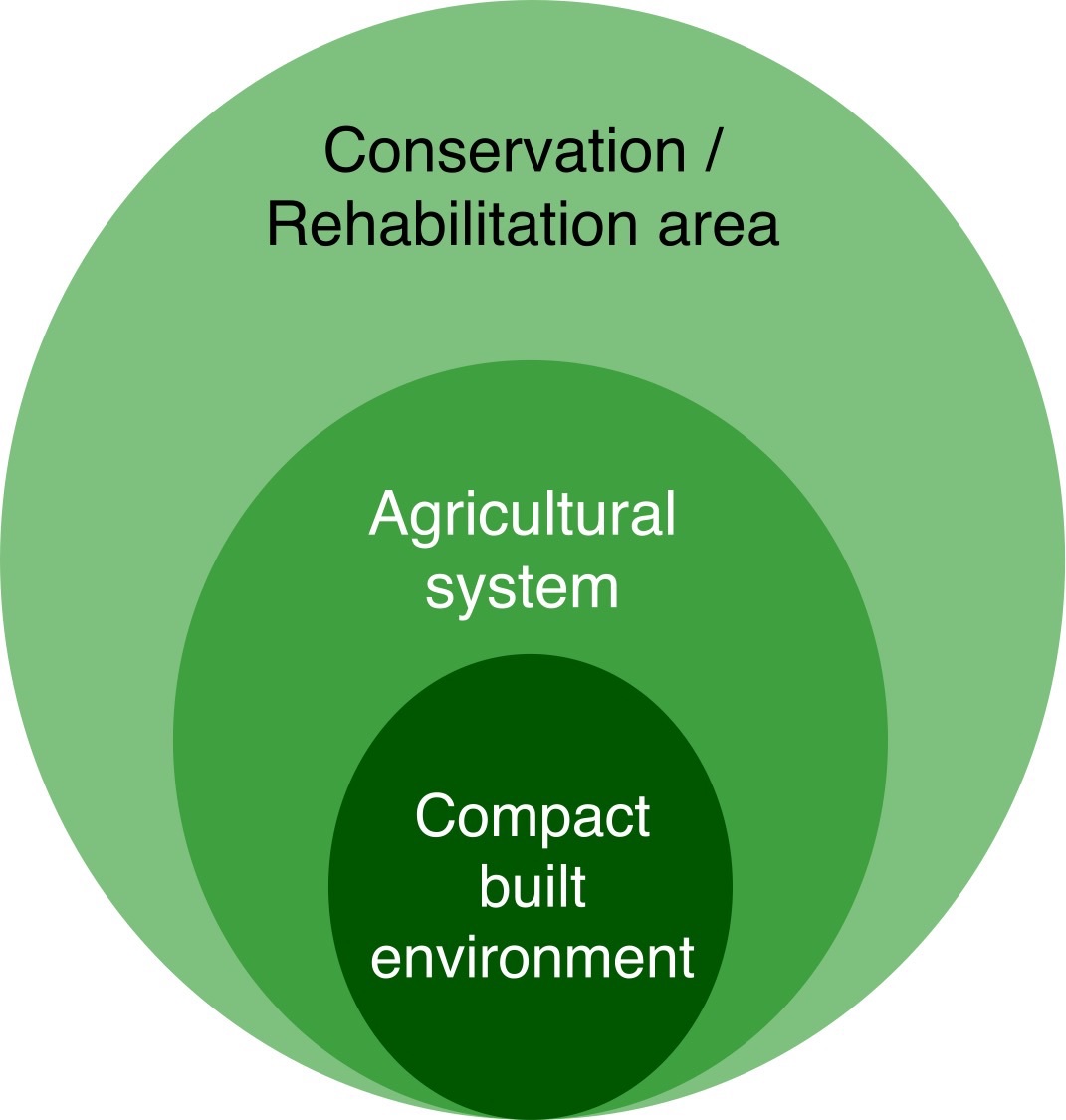

Figure 1. Land precincts schematic - min. 40ha site area, approx. 5ha required for coliving and co-work hub

-

3.2. DEVELOPMENT FORM & STRUCTURE

-

Each hub is proposed to be designed for no more than 200 people and will integrate working and living spaces with water and energy microgrids and a local agricultural food system.

The ideal site would be a minimum of 40 hectares in area. This has been determined based on the land area required to feed 200 people. This is the absolute maximum population but site area and population may be scaled down so that the population matches the carrying capacity of the chosen site. Figure 1 provides a broad schematic illustration of the structure of development.

The five (5) hectare area identified for the compact built environment is equivalent to a low density suburban residential area required to house 200 people although with a pedestrian oriented development and smaller living accommodation, there will be more shared spaces and facilities. The aim is to provide smaller private spaces than is usual for traditional houses but occupants will have access to a broad variety of shared spaces as well as access to food, water and energy.

Locating the site near an existing rural village or town would maximise the benefits for the local community by designing the proposed village to provide complementary facilities and assets to those offered in the nearby locality.

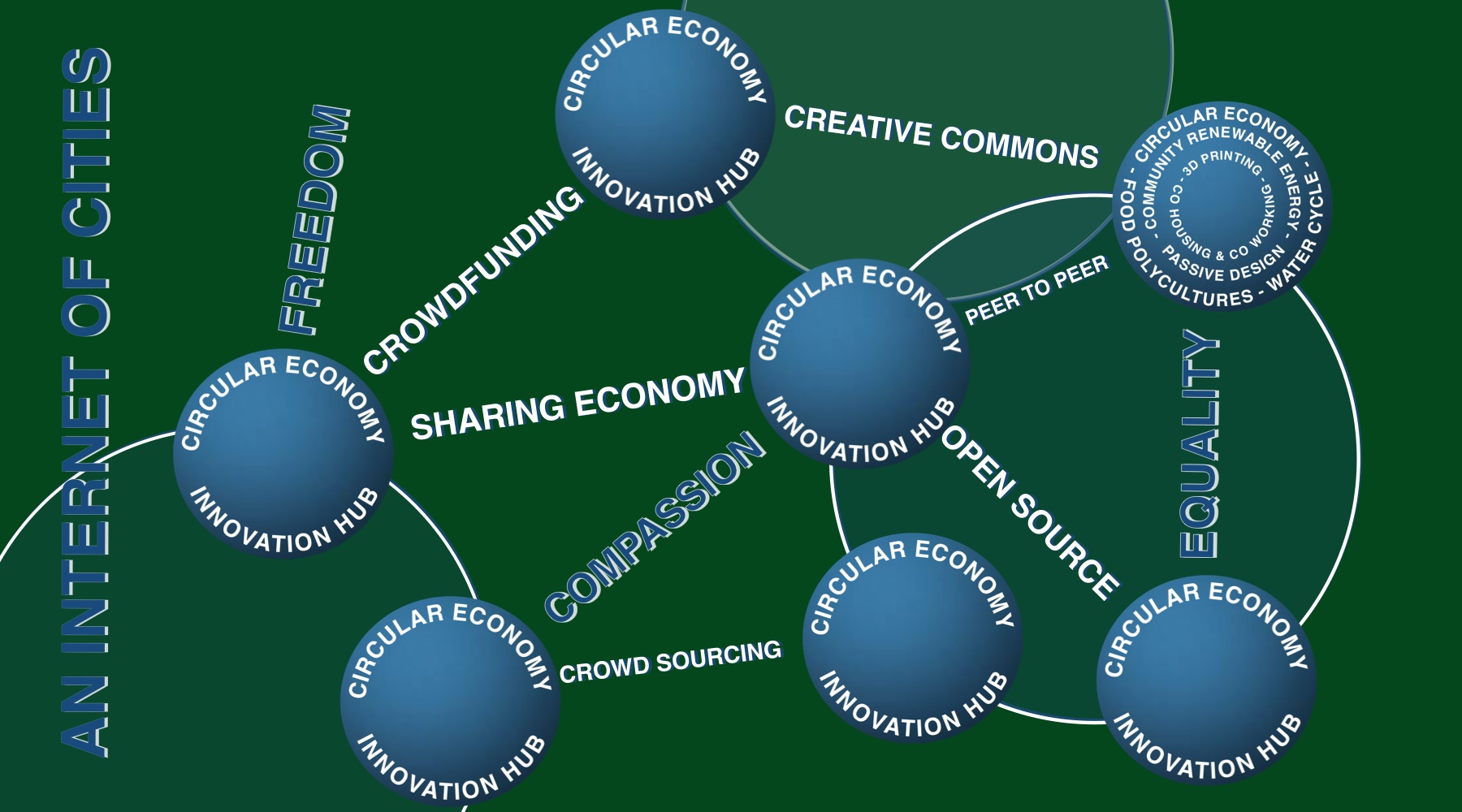

Figure 2. Connected network of hubs

-

3.3. SUBSEQUENT NETWORKING OF HUBS

-

Each hub may remain as a separate entity and will be developed through separate development application processes. Subsequent operators and occupants of each hub may decide to connect in various ways with other hubs to form a network. Whilst the internal design of each hub is aligned with the cyclical ecological systems of its locality to satisfy basic natural needs, the external design is of a network that can operate to satisfy more complex needs or share rarer skills and assets (Figure 2).

Greater resilience and economic efficiency would be achieved by groups of collaborating hubs in a bioregion. The network can also operate as a network of electric vehicle charging stations enabling the sharing of a fleet of various electric vehicles.

4. JUSTIFICATION OF DEVELOPMENT FORM

The proposed development form responds to a range of economic, social and environmental issues, while also adopting the language of current economic disruptions in various industries.

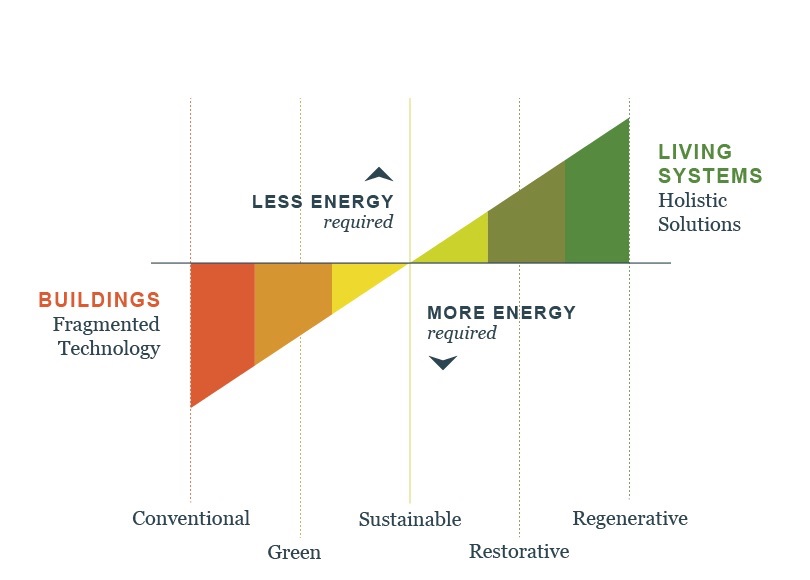

Figure 3. Trajectory of Ecological design (image used with permission)

-

4.1. REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE

-

There are a range of challenges that need to be addressed to guarantee a prosperous future for agriculture in Australia. The effects of a warming climate on agriculture is clear, with increased incidences of extreme weather conditions including droughts, floods and bushfires. These extreme conditions are further compounded by excessive extraction of water from creek and river systems and an unequally distributed irrigation channel system through Australia. Deforestation has resulted in soil depletion and increased salinity. Industrial farming practices over the past 100 years have decreased biodiversity in landscapes & soils, resulting in falling productivity, loss of topsoil & risk to ongoing food production.

Forward thinking farmers like Charles Massy in his book ‘Call of the Reed Warbler—A New Agriculture, A New Earth’ offer numerous examples of various new approaches to agriculture referred to collectively as ‘regenerative agriculture’. Massy is advocating for a revolution in farming practices. Typically, this approach requires significant replanting, initially of gullies and creeks to rehabilitate natural water systems. Increases in natural biodiversity then need to be complemented with biodiverse agricultural systems. Multiple enterprises and complementary land stewardship activities on one parcel of land is more labour intensive and therefore requires more accomodation for farm workers and land managers. This has informed our proposed development structure and the division of the site into precincts as illustrated in Figure 1.

The move towards regenerative agriculture also aligns with the emergence of the concept of regenerative development as a new approach to land development. Proponents argue that we need to move beyond sustainability—sustaining ourselves and the environment—to regenerative development where we have a positive impact. This is best illustrated in the diagram in Figure 3 by Bill Reed from Regenesis. The Circular Economy Innovation Hub integrates regenerative development with regenerative agriculture.

-

4.2. AFFORDABLE HOUSING & COST OF LIVING

-

The issue of housing affordability should be considered more broadly along with other cost of living pressures, including costs of food and electricity as well as transport costs. The cost of land can be minimised by purchasing rural land and capturing the land value uplift associated with the improvements on the site. This is possible if the entity that is operating the site when completed is also the entity that purchases the land at the outset.

With respect to the cost of living, the hub will be designed to provide food, water and energy for a discrete population. Having a known population, allows for the design process to provide for an abundance of these basic necessities. An over-supply of food, water and energy—the demand for which doesn’t vary significantly with price anyway—drives their price towards zero. The passive architectural design of the built environment also reduces energy demand and therefore cost.

The design of a village as a live and work hub also substantially reduces transport costs by having work opportunities within walking distance of living environments. Quality internet connection at the co-working spaces also enhances the option of tele-commuting. A compact design with up to 200 people also makes vehicle sharing more feasible, while the local energy micro-grid can be designed to incorporate an electric vehicle charging station.

-

4.3. HEALTHY URBAN DESIGN

-

According to research by public health professionals, the built environment has an important role to play in supporting human health. In a review of the literature in this field of Healthy Urban Design by Kent et al (UNSW, 2011), three key interventions were identified that could support human health. These are; getting people active, connecting and strengthening communities and providing healthy food options.

The design of the Circular Economy Innovation Hub integrates a food system of significant scale into the built environment providing not just healthy food options but the opportunity to collaborate with others in the community to provide that food. A walkable environment connecting a wide range of daily activities also allows people to get more active. This development model therefore has the potential to significantly improve health outcomes for the resident community.

-

4.4. FROM SEA-CHANGE & TREE-CHANGE TO E-CHANGE

-

Over recent decades, much of the migration from the cities to rural and regional areas has been attributed to individuals seeking a more relaxed lifestyle, that is, a sea-change (to coastal towns) or a tree change (to rural or farming areas).

In 2016 Demographer and Business Analyst Bernard Salt authored a report for NBN Co., in which he suggested that access to the internet is adding another dimension to this migration:

“We are witnessing a quiet lifestyle revolution … The fusion of a relaxed lifestyle in treechange and sea-change locations combined with super connectivity provided by the NBN network, is giving people even greater scope to take greater control of where they live and how they work. I predict a cultural shift or ‘e-change movement’ which could see the rise of new silicon suburbs or beaches in regional hubs as universal access to fast broadband drives a culture of entrepreneurialism and innovation outside our capital cities.” (National Broadband Network (NBN Co. Ltd.) Media Release (Monday 08 February 2016), ‘e-change’ is the new sea-change in 2016)

We believe that embracing the e-change represents an important economic development strategy and opportunity for regional and rural Councils. The Circular Economy Innovation Hub development model would maximise the effectiveness of driving an e-change movement.

-

4.5. ONE PLANET LIVING

-

In the process of satisfying everyone’s needs and aspirations, an economic system should not exceed the capacity of the natural environment to regenerate itself. This is sometimes referred to as living within planetary boundaries or ‘One Planet Living’.

It is a well known principle in economics that, for certain basic necessities, people buy the same amount whether the price rises or falls. The demand for basic needs is said to be broadly ‘inelastic’, which also means that the total amount of food, water and energy needed by households is relatively stable. It is therefore possible to design a place for the needs of a discrete population by estimating their demand for food, water, energy and also living and work spaces.

A key design approach for the development is that it will start with an assumed population size of no greater than 200 persons. The final (potentially smaller) design size will be determined by the capacity of the chosen site and its supporting infrastructure to sustain the population. The community demographics will initially be assumed to be broadly consistent with the age profile of Victoria.

-

4.6. UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME & THE FUTURE OF WORK

-

There is a growing debate and interest in the concept of a Universal and Unconditional Basic Income (UBI). Some of the reasons for the debate include:

- • Concern about the inequality in distribution of income and wealth,

- • A desire to simplify highly strained welfare systems, and

- • The need to address the issue of job losses caused by automation of economic processes.

As technology continues to advance, making many traditional jobs obsolete, it is important to start creating resilient places where people can work to directly satisfy their basic needs, relying less on jobs that provide an income to satisfy these same basic needs. Rather than debating how to fund a basic income in monetary terms, we believe that it would be far more effective and efficient to create places that provide peoples’ basic needs directly.

This also addresses a significant gap in the UBI debate, which aims to address the inequality in the distribution of wealth but does not address how that wealth is created.Regenerative land development complements the UBI debate as it aims to increase our natural capital through restoration and maintenance of land and water, and also plant and animal life, while minimising waste and other negative impacts.

An economic system should also provide everyone’s basic needs as efficiently as possible both in order to minimise energy demand for these activities and also to maximise the free time and space for everyone to pursue more useful and interesting activities.

The development approach supports people as the uncertainty about work in the future increases. It encourages a shift away from land release projects that create dormitory suburbs, by integrating living spaces with work spaces and work opportunities. Work opportunities include the maintenance of the water, food and energy infrastructure as well as management of the shared spaces and facilities. An internal local exchange trading system could be developed in which credit is given to those who contribute to the management of these systems. The management of food systems could include everything from agriculture, food processing, preserving, as well as preparation, cooking, cleaning and management of organic waste. Also, it is proposed to incorporate various waste-to-resource micro-factories to encourage innovative product and business model development using the principles of the Circular Economy. The development will include an office co-working hub that supports the transition away from the work commute to tele-commuting.

-

4.7. TRANSITION FROM A LINEAR TO A CIRCULAR ECONOMY

-

Debates in relation to waste management have transformed in recent years to a discussion about the need for a shift to a circular economy. A useful definition of the Circular Economy is provided by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a leading European advocate of the transition from the current environmentally damaging and wasteful, ‘linear’ economy to a Circular Economy:

Looking beyond the current “take, make and dispose” extractive industrial model, the circular economy is restorative and regenerative by design. Relying on system-wide innovation, it aims to redefine products and services to design waste out, while minimising negative impacts. Underpinned by a transition to renewable energy sources, the circular model builds economic, natural and social capital. (Ellen MacArthur Foundation)

From the above definition we can extract some of the key design principles of the land development project such as life-cycle planning, thinking in systems and striving for zero waste by adopting a restorative and regenerative approach.

It is noted that discussions about a Circular Economy have primarily been in relation to product design to minimise waste. We argue that recent advancements in renewable energy technologies —and associated cost decreases—makes the Circular Economy principles applicable to the design of villages.

Taking a systems approach, an energy micro-grid will monitor and distribute the renewable energy that is generated and stored on site. The energy system will also power a water system that will be cycled through the site, providing for residents, irrigating crops and watering animals. Striving for zero waste can be interpreted as matching supply with demand so the living and work spaces will be passively designed to minimise energy demand. More generally, the energy, water, food and built systems will be integrated to maximise efficiency. Water may store energy or generate energy. Natural systems can clean water and manage water flow quantity. Food waste can improve soil or generate energy using a bio-digester.

5. PLANNING SCHEME IMPLEMENTATION

The feasibility of any business case for a land development project hinges on the level of certainty that a development permit may be obtained. In the following sections we set out the general process for ensuring that necessary permits may be obtained.

-

5.1. CHARACTERISATION OF THE DEVELOPMENT

-

The first step in assessing a proposal requires that the character of the development be identified and a land use term allocated for the principal activity. In the case of the proposed development it would be characterised as a ‘Residential Village’.

Residential Village: Land, in one ownership, containing a number of dwellings, used to provide permanent accommodation and which includes communal, recreation, or medical facilities for residents of the village.

The residential village will include a range of shared spaces including an office work hub and entertainment spaces.

Ancillary activities would also be identified. These include:

Agriculture: Land used to: a) propagate, cultivate or harvest plants, including cereals, flowers, fruit, seeds, trees, turf, and vegetables; b) keep, breed, board, or train animals, including livestock, and birds; or c) propagate, cultivate, rear, or harvest living resources of the sea or inland waters.

‘Agriculture’ is group term and not all agricultural activities are permitted in all zones, so the specific agricultural activities to be undertaken must be identified.

Materials recycling: Land used to collect, dismantle, treat, process, store, recycle, or sell, used or surplus materials.

Some small scale waste-to-resource micro-factories will be incorporated to manage all inorganic waste. This is necessary to satisfy the circular economy principle of striving for zero waste, whilst also reducing waste management costs or charges to Council.

-

5.2. CHOOSING THE SITE

-

The first step in the process of identifying the site on which the proposed development would occur is to determine the zone(s) in which the principal activity of ‘residential village’ is permissible.

In the Rural Living Zone (RLZ), accommodation of all forms are permitted. Therefore residential village is permitted and requires a permit.

Agriculture (other than Animal keeping, Apiculture, Broiler farm, Intensive animal production, Racing dog training and Timber production) are also permitted in this zone.

Given that, as indicated in Figure 1, the compact built environment requires only approximately 5 hectares, while the remaining 35+ hectares will be used for agriculture and for supporting natural systems, this larger area need not be in the RLZ zone. These activities are, of course, also permitted in the Farming Zone (FZ), which also usually adjoins most Rural Living Zones.

This first step in site selection is crucial to the process of obtaining the required permits. There may be circumstances in which sites outside these zones may be selected. To achieve the desired development outcomes will likely require a planning scheme amendment. This is a complex, time consuming and expensive process and requires the approval of the Minister for Planning. We recommend discussing the possibility of the Council supporting such an amendment with Council officers as early in the process as possible.

Other criteria that should also be considered include:

- • Proximity to, or connection with, existing rural townships

- • Access to water (preferably a river or perennial creek)

- • Gently sloping site for water management and terracing

- • Preferably northern aspect.

-

5.3. NO SUBDIVISION

-

Residential villages are not traditional housing developments and as noted in the definition above, relate to “land, in one ownership…”. Accordingly, no subdivision is proposed nor indeed is it desirable.

It is considered necessary to encourage a shift from ownership to stewardship. To achieve this, the entire site must be held and managed as a single integrated ecosystem of infrastructure by a company or a community land trust. Subdividing the site will only introduce unnecessary complications in the management of this system.

Individual ownership should not be conflated with privacy. The design will provide for private individual units.

-

5.4. MASTER PLAN & AGREEMENT

-

The permissibility of the development type is only the first step in the assessment process, which requires compliance with a range of other matters included in the relevant local planning scheme. The proposed development form designed around the principles of a circular economy may not have been anticipated in the preparation of the planning scheme. In such circumstances, it is recommended that a master plan be prepared and maintained for the site. This would be developed in parallel with an agreement with Council. Agreements may be prepared pursuant to Division 2 of Part 9 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987:

- 173 Responsible Authority may enter into agreements

- (1) A responsible authority may enter into an agreement with an owner of land in the area covered by a planning scheme for which it is the responsible authority.

- (a) The minimum total land area and the proportions of the site area for the three (3) precincts (ie. (a) Conservation and/or bush regeneration, (b) Agriculture and (c) Live/Work hub)

- (b) Minimum requirements for harvesting, management, storage and distribution of water, food and energy

- (c) Design principles for buildings

- (d) Affordable housing criteria (noting recent amendments that provide for affordable housing agreements)

- (e) Identification of other infrastructure requirements and allocation of responsibilities between the land owner and Council

- (f) Determination of appropriate Council rates that would be applicable to the land and payable to Council

- (g) Community Engagement processes

- (h) Timing and staging of the development.

-

(2) An agreement may provide for any one or more of the following matters—

-

(a) The prohibition, restriction or regulation of the use or development of land;

(b) The conditions subject to which the land may be used or developed for specified purposes;

(c) Any matter intended to achieve or advance—

-

(i) The objectives of planning in Victoria; or

(ii) The objectives of the planning scheme…

It is proposed to enter into an agreement with the relevant Council to set out the criteria for the development. This would include as a minimum:

- 173 Responsible Authority may enter into agreements

-

5.5. BENEFITS TO COUNCIL & COMMUNITY

-

This project offers a range of benefits to Councils, which should support any application. These include:

- (a) A structured planning process for addressing a number of the key challenges facing Councils such as developing a prosperous local economy, supporting community development, managing impacts on the environment and addressing climate change.

- (b) The project supports the long term financial sustainability of the Council itself as it has minimal impact on existing infrastructure and services, while also providing some community facilities. There is also potential to create business opportunities that harvest waste and convert it into resource material or new goods, thus potentially reducing Council’s waste management costs.

- (c) If appropriately located on the periphery of existing townships, regenerative agriculture provides a managed buffer against bushfires, reducing the risk to people and property. Also, by circulating water through a site, increasing soil volume and soil moisture, as well as generally managing the vegetation, the micro-climate may be altered to reduce the likelihood and severity of bushfires.

This project also offers a range of further benefits to the local community, including:

- (a) Access to new community spaces and work facilities such as a work hub

- (b) Opportunities for the development of business opportunities, particularly with respect to Circular Economy business models that convert waste into resources

- (c) Opportunities to leverage off the research and develop regenerative agricultural models

- (d) Opportunities for eco-tourism, including study tours of the project

- (e) Positive impact on the natural environment

- (f) An option that creates a healthy living environment through social connection, access to organic food and a walkable environment

- (g) Affordable housing options

- (h) Building a replicable model for local resilient communities.

6. DEVELOPING A BUSINESS CASE

-

6.1. OWNERSHIP & RESIDENT ACCESS

-

An important transition is happening in the property development industry. For a range of reasons, rather than building to sell, developers are exploring models referred to as ‘build to rent’ (BTR). This approach is strongly supported by the Victorian government. The most common such model is referred to as co-living. Two of the principal reasons for this transition are:

• Catering for a growing market of urban digital nomads, who don’t want to be anchored to a property but wish to live for extended periods in different cities,

• Continued growth in property prices and in construction costs when compared with the stagnation in wages is making it less feasible to purchase and develop land, then sell it at an affordable price.This shift in the development industry, neatly aligns with our proposal for a co-living development designed as an integrated ecosystem of infrastructure that is held in single ownership. It also aligns with the proposal to provide an attractive development offering for people who wish to make an e-change. E-changers differ from digital nomads in that the former are seeking to escape the city, while the latter love the city-life and seek to travel from city to city. E-changers, as well as the growing cohort of grey nomads and van-lifers represent a significant economic opportunity for rural communities that can offer an attractive and affordable location for these people to stay.

Resident access will therefore be by rental agreement. The minimum period of stay may be determined by each development.

The rental agreement will be with the land owner, which would be a company that is set up to develop and operate such projects. Alternatively, a community may organise to develop such a project. Ideally, they would set up a Community Land Trust that owns and holds the land in perpetuity. A proprietary limited company may still be needed as the trustee of the land trust. The community of future residents could also pool their funds—perhaps together with other investors—as a property development collective, sometimes referred to as ‘Baugruppen’ (the German word for building group). When setting up the investment offering it should be designed so that residents have first right of refusal for any available shares. Over time the investors would be bought out by residents, significantly reducing the outflow of money from the community.

-

6.2. LIFE-CYCLE COSTING

-

Build-to-rent models should adopt life-cycle costing when assessing the feasibility of a project as there is no point of sale and estimate of sale prices. The business case should be developed on the basis of rental income over an extended time-frame, with that rental income to be pitched below market rental rates for housing.

The time-frame over which that capital costs of the development may be depreciated can be maximised by maximising the durability and ease of ongoing management of the building assets. As a general guide the current expected lifespan of a home is in the order of 40 or 50 years. Many buildings in traditional villages are still useful despite being hundreds of years old.

Yet, according to a report by CoreLogic in 2015:

“Across Australia, homes are being owned for longer, with the average number of years a capital city house is owned climbing from 6.8 years a decade ago to 10.5 years over the past twelve months.”

The duration of ownership does not align with the life of the building assets, resulting in the premature demolition of useful buildings. This is another reason for adopting the build-to-rent model and building highly durable buildings. Provided security of tenure is offered for extended periods, there is no meaningful difference between long term secure rental and home ownership.

-

6.3. POTENTIAL FINANCING OPTIONS

-

The following low cost financing options could be considered for such projects.

As the development proposal addresses climate and environmental issues, finance could be obtained (in part or whole) through ‘Climate bonds’ (aka Green Bonds). Climate bonds provide finance for climate change solutions at bond rates rather than usual bank interest rates.

The proposed development methodology is intended to deliver affordable housing. As such financing could also be obtained (in part or whole) from the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC), which provides lower-interest loan finance for registered community housing providers to deliver affordable housing. This strategy would require the developer to be, or to partner with, a registered Community Housing Provider (CHP).

An online platform could be set up allowing future residents to directly invest in a pipeline of projects. This is an extension of the Baugruppen model described above. Nightingale Housing in Melbourne have successfully created such a platform. Their website describes the development model and allows people to join the purchaser list, which now apparently includes several thousand potential purchasers. Mirvac has also launched a build-to-rent club.

-

6.4. POTENTIAL INCOME STREAMS

-

In addition to the rental income from residents, there are a few other income streams that should be considered.

Given that a considerable land area would likely be revegetated there may be potential for carbon farming. There are two approaches to carbon farming. The first is to sell credits into Emissions Trading Schemes (ETS) for restored forests. As Australia does not have an ETS the credits would need to be sold internationally. The second approach to carbon farming is to access funds from the Emissions Reduction Fund in the current Federal Government’s Direct Action Plan to address climate change. There are organisations in Australia who can facilitate this such as Carbon Farmers of Australia.

While the agricultural system should be designed to satisfy the dietary needs of the local population, wholesale or retail sale of surplus agricultural produce could potentially provide additional income. This need not only be the sale of the raw products as it may be preferable to sell value-added produce, where the value-adding has occurred on-site in boutique businesses or potentially even in on-site restaurants that are open to the general public.

Where the renewable energy micro-grid is connected to the National Grid, surplus electricity could also offer a small income stream.

7. CONCLUSION

PolisPlan is now seeking to form partnerships with architects, developers, community groups, Community Housing Providers, finance experts and investors who wish to contribute to the advancement of this development model.

We are also looking for local governments, both elected Councillors and planners, who are interested in facilitating the implementation of the development model in their local government area.