A Case Study in Community Conservation: Reviving a Pheasant-tailed Jacana Population by Ensuring the Survival of the Socio-Economic Landscape in Guantian, Tainan, Taiwan

01.11.2021

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION

Taiwan Wild Bird Federation

OTHER CONTRIBUTING ORGANISATIONS

Pheasant-tailed Jacana Conservation Park

Wild Bird Society of Tainan

DATE OF SUBMISSION

1/11/2021

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Chinese Taipei

LOCATION

Guantian District, Tainan City

KEYWORDS

Community conservation, eco-friendly agriculture, paddy field agriculture, human-wildlife interactions

AUTHOR(S)

Taiwan Wild Bird Federation

Wild Bird Society of Tainan

Forestry Bureau Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan

Railway Bureau, Ministry of Transportation and Communications

Tainan City Government

Taiwan High Speed Rail Corporation

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

1. Beginnings

In the past, the pheasant-tailed jacana (Hydrophasianus chirurgus) had breeding populations in many parts of Taiwan. This changed as many natural wetlands were converted into fish or shrimp ponds, land was reclamation for development, lowlands were filled or damned for water storage, water flows were altered for irrigation, and pesticide use by farmers was rampant. By the late 1980s, Tainan’s Chianan plain was the site of the last stable population in Taiwan. In 1989 the Council of Agriculture declared it a Category II Rare and Valuable Species under the Wildlife Conservation Act. In 1990, initial plans for the route of Taiwan’s then in-development high-speed rail line cut right through important habitat for the waterbird. Before the Environmental Impact Assessment could be approved for the rail line, stakeholders met to discuss the matter. It resulted in the Draft Conservation Plan for High-speed Railway in regards to Pheasant-tailed jacana and other Species which required that “construction of the high-speed rail could only begin after the leasing of 15 hectares of habitat [for pheasant-tailed jacana] has been completed.” The land was therefore set aside and not developed.

Surveys done in 1998 found that there were less than 50 pheasant-tailed jacanas remaining in the Taiwan, particularly in areas doing water chestnut (also known as water caltrop) cultivation. It was also that year that the Taiwan Forestry Bureau and Tainan government launched the Incentives to Protect the Pheasant-tailed Jacana Plan. The plan was meant to ensure the protection of jacanas by subsidizing farmers cultivating water chestnuts that had jacana nests on their property.

In January 2000, government agencies and conservation groups came together to establish the Pheasant-tailed Jacana Rehabilitation Area (PTJRA) in Tainan’s Guantian District. At the same time, local groups, especially various Taiwanese bird societies, and Wetlands Taiwan worked together to implement the Pheasant-tailed Jacana Conservation Plan which aimed to create suitable habitat for pheasant-tailed jacana. In 2007, the plan was considered a success as there was a more stable population size and greater available habitat. With this foundation laid, it was decided that the plan should be revised to incorporate more goals related to conservation education and outreach with the local community. Thus, the Pheasant-tailed Jacana Restoration Area was renamed the Pheasant-tailed Jacana Conservation Park (PTJCP) and given new focuses related to promoting ecological conservation education and community conservation activities. The main purpose of the park is still to serve as a reserve for pheasant-tailed jacanas. At the on-site conservation and natural resource center, staff monitor the changes in Tainan’s pheasant-tailed jacana population. A conservation strategy has also been devised to incorporate the use of information sessions and ecological education activities so that the public can understand the ecological importance of pheasant-tailed jacanas and nature conservation.

Photo 1. Young Pheasant-tailed Jacanas in a Water-Chestnut Field

2.1. Creating a Biodiversity-Rich Wildlife Reserve

Park staff have engaged in long-term restoration planning, adopting a habitat management model comprised of a combination of manpower and modern innovation to recreate and improve both the wintering and breeding habitat required by jacanas in the area. The goal was to raise the number of pheasant-tailed jacana in a sustainable and steady manner. Due to the hard work of park staff and their actions in the community, around 100 new jacanas are now added to the park’s population each year.

Plants in the visitor area have also been chosen and placed in such a way that it has now transformed the area into a forest habitat, providing food and safety for other local species such as Light-vented Bulbul, Swinhoe’s White-eye, Taiwan Barbet, and Crested Goshawk. The park’s wetlands have also developed into a stopover site for various migratory bird species. Also, through maintaining an eco-friendly management philosophy and a successful environmental outreach campaign with the community, now many wild animals can be seen throughout the park.

Yet with just 15 ha. space is limited. Birds therefore must leave the safety of the reserve in search of other quality habitat. In fact, the March rice harvest coincides with younger pheasant-tailed jacanas leaving the park in search of suitable breeding habitat. Yet finding a place can prove challenging, and sometimes deadly. In winter, certain local farmers put out poisoned bait in an effort to combat wildlife take of their direct-seeded grains. This leads to the death of pheasant-tailed jacanas every year.

This understanding led to an adjustment in the park’s conservation strategy. The PTJCP now realizes it only serves as a core area for the population. Meanwhile, farms outside the park are encouraged to become more sustainable and eco-friendly. To this end, farmers are encouraged to practice eco-friendly farming and sustainable agricultural practices to preserve the type of habitat necessary for jacanas to thrive. Areas outside the park have also been evaluated as potential jacana “hot spots” beginning in 2010. These are defined as locations with over five jacanas or over thirty birds of different species. Each year different locations are added to the “hot spot” list and in 2018 there were 21 locations selected.

2.2. Promoting Traditional Agricultural Practices and Addressing Human-Wildlife Conflict

Tainan City’s Guantian is Taiwan’s largest water chestnut producing area. It’s farmlands are agricultural wetland ecosystems altering between rice and water chestnut cultivation. As such, in the winter the rice paddies provide ample food for migratory birds while in the summer the floating water chestnut leaves provide the necessary nesting materials that breeding pheasant-tailed jacana require. This annual dance of agriculture and biodiversity makes for a distinct ecological and cultural landscape.

After the water chestnut harvest in the fall/winter, rice is planted. However, since water chestnut fields are generally muddier than the average rice paddy, plowing and transplanting machines often get damaged. Therefore, some farmers do direct seeding. They can save around $2,500-$3,000NTD this way, with a yield potentially higher than that of using transplanted rice. However, direct seeded rice can easily be taken by birds, mice, or other animals. Therefore, in the past, farmers added pesticides such as Terbufos, TOEFL, and Phorate to the seed as a form of pest control. This led to a significant number of deaths, not just for pheasant-tailed jacanas, but other wild animals as well.

In 2009, staff found that 85 pheasant-tailed jacanas in Guantian died of poisoning. That year, only 52 jacanas fledged at the PTJCP. The staff consulted the Forestry Bureau on how to address this problem. They also connected with the Tse-Xin Organic Agriculture Foundation who assisted them in implementing the Protecting Birds from Poisoning Compensation Plan and began the process of developing a “Green Conservation Label” certification for organic farming production. In the beginning, farmers were willing to try and get the certification. However, the stress on planting increased, as did the cost of production due to the increase of pests and factors related to climate change. In the end, the farmers withdrew from the project if their income was negatively impacted. The return to conventional farming practices included the use of pesticides, and poisoning incidents for birds continued to occur. It was also discovered in 2014 that some of the farmers who had joined the “Green Conservation Label” trials were still using poisoned bait and killing birds. Staff realized then that even though farmers agreed to use the “Green Conservation Label”, they did not agree in principle or behavior. There was also no change towards more eco-friendly practices. Other ways to work with the farmers needed to be developed.

Photo 2. Pheasant-tailed jacanas live in agricultural ecosystems

Photo 3. Local water chestnut farmers display logo of brand which has received Green Conservation Label verification

3.1. Building Bridges with Local Farmers to Inspire Change

Each winter starting in 2009, to better understand the conditions of the farmland and wetlands outside the park, park staff would patrol the water chestnut fields in Guantian and nearby areas. Through these activities, it was discovered that farmers were not just putting out poisoned bait, but were hanging carcasses as well. This was done to scare birds. In the past there were many Black Kites in Guantian. Birds were frightened to eat the grain with them hovering in the sky. But then the Black Kites disappeared. With them gone, tree sparrows and turtledoves had become bolder and would eat the rice. In response, farmers hung up the carcasses as a warning. After the patrols started though, the farmers were afraid that they would be reported for having the bird carcasses in their fields. They then started employing different tactics for killing the sparrows and turtledoves. This included reducing the concentration of pesticides in the bait they put out in the hopes that the birds would die in someone else’s field. They would also put the poison bait at the edge of their property to increase the chance that the birds would take the bait and die elsewhere. The problem was widespread. Even some farmers who were participating in a government-funded subsidy program which provided funds for farmers with jacanas on their property (the Pheasant-tailed Jacana Nest Subsidy Program) were still using poisoned bait.

Park staff looked into the matter and got some interesting results. They found that 80% of farmers did not know that jacanas were being poisoned, and more than 90% of the farmers didn’t know that jacanas had non-breeding plumage in winter. To inspire change, park staff realized that they needed to look at things from the perspective of the farmers.

Therefore, the PTJCP team decided they would patrol the farmlands and wetlands in Guantian and neighboring areas during the peak poison bait season from December to January each year. As they did the patrol, they would also make efforts to communicate directly with farmers, respect their opinions, and strive to gain mutual trust. The staff knew they needed to help the farmers understand the jacana’s wintering behavioral ecology while at the same time valuing their hard work and livelihood.

The staff also worked with companies, universities, local government offices, and civic groups to do more to promote the conservation of jacanas while at the same time respecting the farmer’s concerns. This included working to develop environmental education materials, increasing the value of local eco-friendly agricultural products, establishing community-friendly farming communication platforms, engaging with corporate social responsibility, encouraging eco-friendly and organic farming, and helping solve the problem of birds harming crops.

Farmers who received subsidies for having nesting pheasant-tailed jacana on their land had a good impression of the birds. They would then talk with other farmers about the need to protect them. Also, the staff that did the jacana surveys and patrols gradually gained the trust and acceptance of the farmers. With these positive developments, farmers began to adjust what they used for keeping birds out of their fields. These items included bird repellent balls, flags and fans. Park staff also helped to raise funds from companies and the public to purchase or make products that farmers could use in order to deter the birds instead of using poison bait.

At present, 95% of the water chestnut farms in Guantian have joined in on this initiative. Therefore, the number of pheasant-tailed jacana has exceeded 1,000 each year since 2016. After further observation and analysis based off of the patrols, it is now understood that eco-friendly farming is the only way for farmers to coexist with pheasant-tailed jacanas. Park staff therefore decided to take all they had learned and done over the years and promote organic and eco-friendly farming to the wider community starting in 2014.

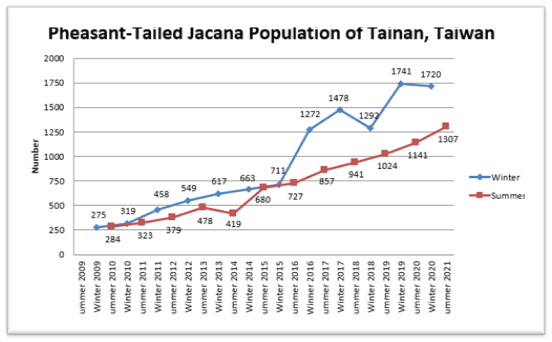

Chart 1. Change over time for Tainan’s Pheasant-tailed jacana Population

3.2. The Eat Water Chestnuts to Help Pheasant-tailed Jacana Initiative and Results

Pheasant-tailed jacana habitat outside of Taiwan is mostly dominated by water cabbage. However, water cabbage does not provide sufficient food and is an unstable material for the creation of jacana nests. Meanwhile, water chestnuts are a cultivated agricultural product with a history going back over 100 years in Taiwan. Not only that, but in addition to being a source of sufficient food, jacanas prefer to build their nests on the leaves. Their stability as a nest-building material is ensured by strong water chestnut production.

Without water chestnut cultivation, the future of Taiwan’s pheasant-tailed jacanas would be put in danger. Therefore, the PTJCP teamed up with local farmers for the Eat Water Chestnuts to Help Pheasant-tailed Jacanas initiative beginning in 1997. It was a slogan campaign featuring a slogan that was easy to remember and involved food, and played on the fact that everyone is interested in food. The goal was simple, get people to remember and say the phrase. By doing so, people were promoting sustainable cultivation of water chestnuts in Taiwan without thinking about it. This not only helped the industry towards evolving and allowed farmers to obtain economic stability, but promoted the integration of agricultural production and ecology as well. It created a new force for the preservation pheasant-tailed jacana habitat. The PTJCP actively promoted it to park visitors, during park-held camps, and at schools as well as communities, so that this agricultural practice and ethos could be better understood and valued. Staff also began going to farms on a regular basis to talk with farmers and discuss their views on the conservation of pheasant-tailed jacana. Farmers would even start coming to the park to ask for advice when they encountered pheasant-tailed jacana nests or on matters related to government subsidies. The park, in essence, had become a resource center for farmers and those looking to help them.

Photo 4. Using flags to repel birds

Photo 5. Using wind to repel birds

4. Doing Citizen Science Projects to Help Pheasant-tailed Jacana

Since 2015, the PTJCP has been engaging in citizen science projects and has used the Lab of Biodiversity Indices created by the Taiwan Endemic Species Research Institute (TESRI) to conduct pheasant-tailed jacana surveys. These projects have attracted participants from all over Taiwan who are interested in doing field communications and observations or who are looking to understand the habitat and environmental needs of pheasant-tailed jacanas.

Every summer, from May to June, farmers plant water chestnuts. In July, as the plants grow and become denser, pheasant-tailed jacanas will spread out as they search for nesting areas. The last week of July was selected to do the Pheasant-tailed Jacana Summer Breeding Survey. Those studying in areas related to biology and ecology are invited to serve as volunteers. It is hoped that their passion can also inspire farmers to care more about local ecology.

The PTJCP’s winter survey of pheasant-tailed jacanas takes place the first Sunday of December. It is promoted via social media and any bird lover interested in pheasant-tailed jacanas is encouraged to participate. The event lasts half-a-day and participants do the count in blocks. In accordance with the standard procedure established by TESRI’s Lab of Biodiversity Indices, the survey lasts from dawn until completion, and results are announced on the same day. Every year, nearly 100 participants join the event. This helps foster knowledge about pheasant-tailed jacana habitat and traditional agricultural practices.

5. Creating Environmental Education Activities and Encouraging Direct Purchase of Agricultural Products

Park staff have worked on a number of educational games and activities in order to better share the message of nature coexisting with agricultural production. In 2011, the park staff developed a game to educate people about the behaviors, habitats, and challenges faced by pheasant-tailed jacanas. There is also a day camp style activity for parents and children. This experience allows families to learn together and create a connection with the land, creating strong bonds between people and place based on shared experiences. Such activities have proven to be especially important for children.

The PTJCP has used its popularity to promote eco-friendly and organically farmed agricultural products. For many, after participating in environmental education activities at the park, they are quite interested in purchasing locally grown eco-friendly agricultural products. This is one way to show that they care about local ecology and have a better understanding of the relationship between agriculture and ecology. The purchase of such items not only supports farms, but is also healthier. On a broader scale though, it helps support a better relationship between agricultural production and ecology. Promoting and supporting such purchases is an effective environmental action strategy.

Another activity is the Visit to A Farmer’s Home. Here, participants travel to a farmer’s home outside the park and learn about their life, land, and relationship with nature. Park staff are in constant communication with the farmers to help them as they create their special itineraries. This allows the farmers to better understand the needs of the guests. Activities are planned by the farmers with the assistance of park staff, who then look for ways to combine it with an environmental education experience camp. During the visit, farmers usually take some time to share their personal experiences and then relate information about some of the special local foods they have. Guests can then directly buy the agricultural products from the farmers. Creating this experience is an effective way to establish a relationship between farmers and non-farmers and promotes a dialogue between people and the land. Supporting the direct purchase of agricultural products also creates a more diversified distribution model so that the preservation and innovation of agricultural skills can continue. Farmers appreciate and value the fact that they have an opportunity to share their story and create their own itinerary for those interested in their lives and work. It increases their feeling of attachment to the community and environment. With such affirmation and support from the community and family members, eco-friendly farming is able to continue and the chances of preserving the natural ecosystem is possible.

Photo 6. The use of biodiversity for brand imaging.

Photo 7. Farmers teach students how to plant rice seedlings.

Conclusion:

The Pheasant-tailed Jacana Conservation Park is a model for how to balance development and conservation. Due in no small part to its success, the water chestnut industry is able to thrive outside the park while maintaining biodiversity in this truly rich socio-ecological production landscape. The park has worked tirelessly to establish a strong bond between people and the land through providing farming experiences, promoting dialogue between producers and consumers, and creating a diversified distribution model so that traditional agriculture practices can be preserved. The care and support provided to the farmers inspires them to have a deeper sense of responsibility to the community, including to wildlife. This has a direct impact on their willingness to continue doing eco-friendly and organic farming. The local ecology can thus be preserved, promoting the harmonious coexistence between humans and nature.

For More Information About the PTJCP Please Watch the following video:

Appendix 1: Overview of Activities Done by the Pheasant-tailed Jacana Conservation Park

I. Educational:

A. In Park:

1. Environmental Education Activities:

-Games for students (themes: ecology, land exploration, aquatic creatures)

-Park Tours

-Birdwatching Activities

-Experiential activities (planting water chestnuts, night time frog safari, water chestnut harvest, harvesting wild bamboo shoots, lotus root digging, pulling weeds)

2. Talks

3. Working with schools to ensure visits to the park fulfil school environmental education requirements of schools

4. Student volunteer opportunities (e.g. interpreters)

5. Class on innovative cuisine featuring water chestnuts

6. Full day food and agricultural education event. Features on-site introduction to aquatic plants and plant collection. The food items cooked on site to make traditional water chestnut dishes.

B. Outside Park:

1. Talks

2. Ecological games

3. Visit to an eco-friendly farm and featuring DIY course (peeling water chestnuts, painting water chestnut husks, dyeing cloth with water chestnuts, etc)

4. Visit to a Farmer’s Home activity

5. Arts and crafts course developed in conjunction with local artists using old water chestnuts (dying cloth or make incense)

6. Innovation cooking and flower design class featuring local artist (using water chestnuts as theme item)

II. Collaboration with Farmers

A. For Farmers Participating in Green Label Program

-Help farmers to develop branding and design packaging for agricultural products

-Help farmers better promote their agricultural products.

-Serve as a representative between farmers and major distributors discussing price negotiations.

-Encourage businesses to give farmers more reasonable prices for purchases as part of CSR.

-Help farmers to find agricultural experts for improving field management, doing pest control, and providing overall guidance.

-Encourage farmers to diversify their portfolio (i.e. help farmers to create plans for environmental education camps with experiential activities)

-Train farmers to become activity planners and instructors

-Help develop innovative recipes and creative dishes

-Organize outdoor performances and events in farmer’s fields to raise the level of local food culture.

B. General Actions

1. Patrol farmland wetlands

2. Actively communicate with farmers in the field

3. Hold talks to learn why farmers use poison bait; share info with gov agencies.

4. Assist farmers to control issues related to bird and rodent control.

5. Actively engaged in finding and sharing alternatives to poison bait for rodent control.

6. The park has become a resource hub for farmers where they can find information and inquire about different kinds of agricultural assistance from government agencies.

III. Government Agencies and Business

1. Serve as a communication platform highlighting what government agencies and businesses are looking and matching them with suitable farmers.

2. Represent the needs of farmers to government agencies to help all parties find solutions.

3. The PTJCP is part of the National Ecological Network connecting both government and NGOs to farmers.

Appendix 2: Structure and Methodologies Used by Pheasant-tailed Jacana Park towards Conservation and Satoyama Initiatives

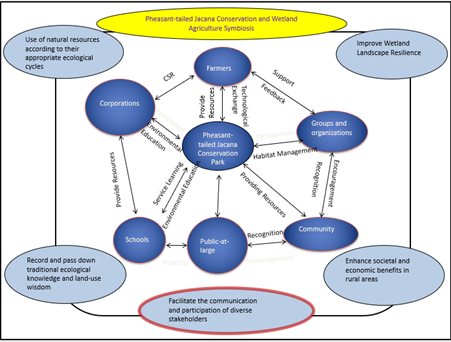

1.Structure of PTJCP and Stakeholder Relationships towards Creating Wetland Agricultural Symbiosis

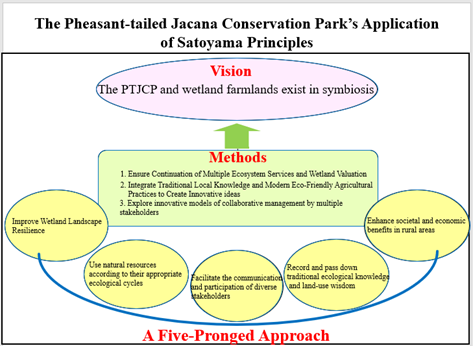

2.The Pheasant-tailed Jacana Conservation Parks Application of Satoyama Principles

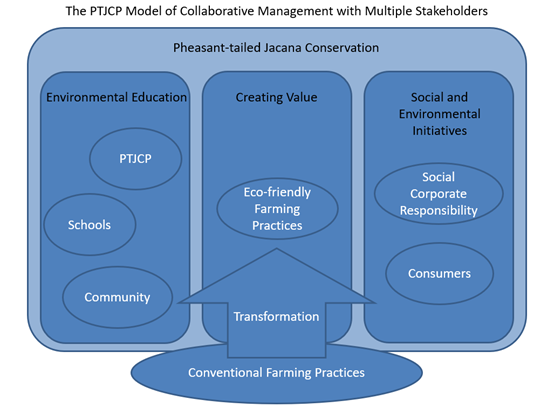

3.The PTJCP Model of Collaborative Management with Multiple Stakeholders