Integrating community development with the management of grasslands and wetlands at Ke’erqin nature reserve

27.02.2012

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Renmin University of China

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

27/02/2012

-

REGION :

-

Eastern Asia

-

COUNTRY :

-

China (Inner Mongolia)

-

SUMMARY :

-

Since 2007, with the support of the UNEP/GEF funded Siberian Crane Wetland Project, various community development activities in the Beizifu community have been carried out at Ke’erqin National Nature Reserve in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. These community activities covered a wide range of elements for an environmentally-oriented integrated development approach: restoration of traditional cultures, empowerment of local communities, self-organization, rural bio-energy, establishment of community revolving funds, promotion of micro-enterprises, participatory pasture management planning and monitoring, environmental education, and establishment of the community-initiated Beizifu Ke’erqin Pasture Protection and Management Association. Based on this intervention, this paper documents the reflections on key points for identifying interventions and projects in the Beizifu community supporting community-based natural resource management. These points are: translating the conceptual strategy for intervention into an operational strategy, targeting model and orientation, identifying actions supporting community-based resource management, developing trust between outsiders and the community, changing the behaviour and attitudes of local officials, and monitoring and evaluation of community actions. Finally, this paper reviews some critical issues for development interventions at the community level supporting sustainable natural resource management and biodiversity conservation, including development intervention, unification of community, culture - in particular traditional culture, and centralization and decentralization.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Biodiversity Conservation, Community Co-management, Community-based Natural Resource Management, Community Development, Traditional Culture, Wetland Management

-

AUTHOR:

-

Liu Jinlong, Professor, Director, Centre for Forestry and Natural Resources Policy Study, Renmin University of China James Harris, International Crane Foundation, Zhao Lixia, China Agricultural University. Jiang Hongxing, Associate Professor. National Bird Banding Center of China, Research Institute of Forest Ecology, Environment and Protection, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China Qian Fawen, Associate Professor. National Bird Banding Center of China, Research Institute of Forest Ecology, Environment and Protection, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China

BACKGROUND

Within the past thirty years, the total area of nature reserves in China has rapidly expanded to 14% of the country’s total land area, providing protection for endangered species and representative ecosystems in a qualified sense. Traditionally, natural resources allocated for conservation would be used by local communities, and these conservation areas are often located in economically underdeveloped regions with poor transportation facilities and far from city centres. Therefore, the livelihood of local people should depend on natural resources which are ‘allocated’ for conservation. For a long time, executive orders, laws and regulations have been the main measures for resolving conflicts between natural reserve protection and peripheral communities. However, because objective requirements for the survival and development of local communities were ignored, conflicts between conservation areas and communities became increasingly intensified.

On the other hand, the nature conservation sector in China has gradually assimilated new ideas from international natural conservation practices, including the important approach of community co-management. In China, community co-management has transformed from a concept into a practical action for nature conservation. With the initiative of the Beizifu community of the Ke’erqin National Nature Reserve (NNR) in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, starting from 2007, the UNEP/GEF Siberian Crane Wetland Project (SCWP) has supported some pilot community development activities. Over the past 3 years, the project facilitators, the local community and the nature reserve staff jointly achieved progress in the direction of community-based resource management and biodiversity-friendly economic livelihood alternatives. At the same time, questions arose concerning some intervention actions. This paper focuses on development intervention supported by SCWP in the Beizifu community, and documents our experiences in the process of community intervention towards developing a co-management scheme for natural resource management and biodiversity-friendly alternative livelihoods. Based on this intervention, the authors wish to share their reflections from the perspective of development sociology.

1. MATERIALS AND METHODS

1.1 Basic Information on Beizifu Gacha (Village)

The Beizifu Gacha (hereinafter referred to as the Beizifu community) is located at the center of the Ke’erqin Sandy Land Region, with four natural villages, 233 households and a population of 890, 95% of which are ethnic Mongolians. Ke’erqin Sandy Land Region, the largest such sandy soil area, is a typical semi-arid region lying between farming areas and deserts in Northeast China. This is one of the most fragile regions, sensitive to human disturbance and natural calamities such as rainfall shortages and increased temperatures associated with climate change. Historically, the Mongolian people created their own culture associated with grazing the vast pastures of this region. “Beizifu” means “mansion of the nephew of the king (from the Qing Dynasty of China)”, where an area with about 20,000 ha of land was presented to this nephew. With population growth, farming has been introduced in recent decades. The prolonged drought has threatened farming and grazing activities, people’s daily lives and traditional culture. Yields of maize fluctuated greatly from year to year, and the natural pasture and savannah ecosystem was seriously degraded. During a baseline survey in the Beizifu community before starting the community development project, the local people ranked degradation of nature resources including pastures and wetlands, and lack of rainfall, as the primary threats to their livelihoods, and the future of the community.

Due to resource degradation, the Beizifu community, as one of the representative communities of the Ke’erqin Sandy Land Region, was marginalized during the process of rapid economic progress in China. In 2007, the average net income per capita in the community was about 900 yuan (about 132 US$), far below the national average of rural farmers, at 4,140 yuan (about 608 US$). Farming (maize and mung beans) and livestock raising (sheep and cattle) are the main income sources. In recent years, revenue from off-farm income has sharply increased, and more and more young people are seeking migrant jobs.

In recent years, many initiatives have been taken by local governments to offset resource degradation and to alleviate poverty in the Ke’erqin region, including the introduction of a grazing ban, genetically modified livestock, and eco-energy initiatives. These measures have achieved some positive impacts; however it is necessary to assess how the communities interpret these interventions in their production practices. These initiatives intended to safeguard natural grassland, wetland and savannah ecosystem with joint efforts from individual households, collectives and the state.

Beizifu community, the majority of whose territory is located in the core zone of Ke’erqin NNR, and it is unique in some aspects of its ecosystem complex including rare cranes and wildlife. However, it is a typical representative of communities in the nature reserve with rich resources, poor community, rich traditional culture, poor governance, and social and ecological fragility to outside intervention.

1.2 Ke’erqin National Nature Reserve

The Ke’erqin Wetland and Rare Bird National Nature Reserve is located within the borders of Xinjiamu Sumu (Township), in the northeast part of Ke’erqin Zuoyi Zhongqi (county) of Xing’an League (Prefecture). The geographic coordinates are 44°51′42″ – 45°17′36″ N, 121°40′13″ – 122°14′07″ E. The northern boundary of the conservation area is close to Tuquan County of Xing’an League, the eastern boundary side is contiguous with Xianghai NNR in Jilin Province, the southern boundary is the Huolin River, and the western boundary is 27 km from Bayanhushu Township, the capital of Ke’erqin Zuoyi Zhongqi; the north-south length is approximately 46 km, the west-east width is approximately 44 km, and the total land area is 126,987 ha.

Ke’erqin is a comprehensive National Nature Reserve protecting the basic structure of the Ke’erqin Grassland ecosystem to a relatively complete degree, including three representative landscapes: wetlands supporting rare birds, native elm (Ulmus macrocarpa var. mongolica) forest and Ke’erqin Grassland. There are 175 species of birds within the conservation area, including seven bird species with first-grade state protection: Oriental Stork Ciconia boyciana, Black Stork C. nigra, Red-crowned Crane Grus japonensis, Siberian Crane G. leucogeranus, Hooded Crane G. monacha, Great Bustard Otis tarda and Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetus. Also, there are 29 bird species with second-grade state protection. The globally threatened bird species occurring in the reserve are the Oriental Stork, Red-crowned Crane, Siberian Crane, White-naped Crane G. vipio, Hooded Crane, Swan Goose Anser cygnoides, Baer’s Pochard Aythya baeri and Great Bustard. The species resources of cranes and storks are a key conservation value of the reserve. China has nine of the world’s 15 crane species, the largest number of any country. There are six crane species in the conservation area: Hooded, Eurasian G. grus, Red-crowned, White-naped and Demoiselle Cranes Anthropoides virgo. Demoiselle Cranes also breed in the local area.

In addition, there are 452 species of angiosperms within the conservation area. There are 3,000 ha of Siberian Apricot Prunus sibirica secondary forest, which occurs in different densities, and is an element of the original landscape of Ke’erqin Grassland together with grassland and open elm forest. As one of the three largest grasslands in Inner Mongolia, there is not much remaining of the Ke’erqin Grassland outside Ke’erqin NNR due to continuous drought and the rapid development of livestock breeding.

In 1985, the Ke’erqin Nature Reserve was established at the prefecture level, and in 1995, it was upgraded to a National Nature Reserve. Ke’erqin NNR has struggled in recent years to safeguard its natural grassland, wetland and savanna ecosystems with rare cranes and wildlife in the face of growing pressure from Beizifu and the residents of other villages for grazing and other resource uses. Prolonged drought has threatened biodiversity and the welfare of local communities at Ke’erqin, and has increased conflict between conservation and development needs. Through many years of management practices, the reserve leadership and technical staff have realized the need and potential for community-based development to enhance resource protection and sustainable use while enabling the reserve to meet its conservation objectives in partnership with local communities.

1.3 Research methodology

An action research methodology was used as the fundamental data gathering approach. Action research is “learning by doing”, contributing to the practical concerns of the local people in an immediate problematic situation and simultaneously furthering the goals of social science (Gilmore et al., 1986). This approach requires collaboration between researchers and local people through shared learning and reflection. We provided trainings to the local community and nature reserve staff and assisted them in designing, implementing, monitoring and evaluating the community development intervention. They learned and then applied what they had learned to implement the work themselves. As researchers, we were able to conduct research in a real-world situation, aiming to solve real practical problems.

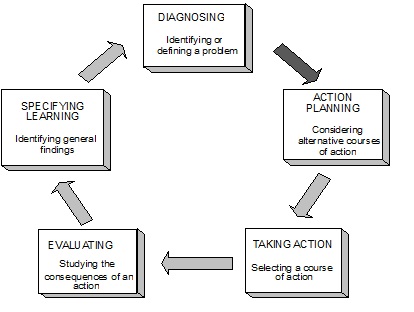

We followed five phases as developed by Susman (1983) (see Fig. 1). Initially, problems were identified and data collected for more detailed analysis. This was followed by the collective proposal of several possible solutions, from which a single plan of action emerged and was implemented. Data on the results of the intervention were collected and analyzed, and the findings were interpreted in the light of the action’s success. At this point, the problem was re-assessed and the process began another cycle. This process continued until the identified problems were resolved.

Figure 1. Detailed Action Research Model (adapted from Susman 1983)

Over the past three years (2007-2009), the authors worked with the local community to manage the community’s natural resources, and developed a good rapport with the villagers, adopting time-efficient, participatory primary data collection approaches in addition to the accumulated secondary data. Strong emphasis was given to participatory techniques and ethnographic modes of data collection. We lived in the Beizifu community to understand the people’s daily livelihood activities in relation to fengshui forests (forests with symbolic spiritual meanings, and being strictly managed by local communities, and usually serving ecological functions), using a participatory observation method. This approach along with semi-structured interview and group discussions were our first hand data collection methods.

Semi-structured interviews were carried out with key informants. These included Nature Reserve officials, community heads and villagers, and officials from the county and township governments. These key informants were involved in the process of community intervention together with the researchers. Group discussions including elders, men, and women in the villages were organized to discuss three main topics. The first topic was related to cross-checking the data collected and provided by key informants. The second topic concerned influential, big events (including national and local policy adjustments) in the history of natural resource management and utilization, and their impact on specific locations. Finally, these discussions considered the functions, management, utilization methods, activities and benefits relating to natural resources. During group discussions, visual tools, including participatory mapping and ranking, were used for analysis.

Analysis of data from interviews, combined with information derived from situational analysis and case studies, was used to explore the research questions and to arrive at specific conclusions. Hence different bodies of original yet sometimes fragmentary data were organized into a format relevant to the investigation. Such data treatment measures covered comparison, analogy, induction, deduction, reasoning, and summarization – each designed to identify existing processes and problems for further inquiry.

This research was a reiterative process. We analyzed data during the fieldwork period and adjusted our research plan according to activities taking place in the field. We tried to do research together with local people and based on the villagers’ perspectives. This is a good way to do research from within, according to Struthers (2001). Besides soliciting data to meet our research objectives, we also developed friendships with the participants through our frequent interactions with them.

2.INTRODUCTION OF THE DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTION IN THE BEIZIFU COMMUNITY

Prior to initiating the community development activities in the Beizifu community in Ke’erqin NNR in 2007, a series of trainings were provided to reserve staff and officials from local governments, including: in-class training on participatory rural appraisal (PRA), co-management planning, and sharing-learning among Nature Reserve staff under the project, and domestic and overseas study tours on co-management and integrated rural development. After the community project was initiated in the Beizifu community, these trainings were continued and expanded to more participants including village heads and progressive farmers. These trainings provided a fundamental base for them to acquire and apply new knowledge in the community development processes.

In 2007, the Beizifu community-based resource management action started with a week-long training workshop on participatory appraisal and planning. The primary goals of this training were: to develop multi-stakeholders partnership mechanisms; to expand the social network for people in the community; and finally and most importantly to conduct integrated community development planning for the Beizifu community. This training was facilitated by the researchers, and Participants included individuals from the Nature Reserve, technicians from county forestry and livestock bureaus, representatives of the township government, and village heads and farmer representatives. As a result, a multidisciplinary team was established to analyze the problems and challenges they faced, the advantages and disadvantages they have, the opportunities and potentials they hold, and thus to develop an integrated community development plan to guide the three year intervention.

The plan aimed to develop an integrated biodiversity-friendly community development model. In other words, through the implementation of a series of developmental subprojects, assisting with ecological culture instruction activities, giving full play to community members’ initiative in participating in natural resources management, especially grassland management, and gradually adopting sustainable community-based grassland management; adopting and testing the idea of participatory planning, establishing a framework for community development within the next two years, making adaptive adjustments to the implementation process based on new situations and popular will, developing farmer organizations and enhancing capacity building through study tours, training and learning.

The villagers were initially interested in converting their goat herds from a local variety to a new (more expensive) breed that can yield greater profits through cashmere (goat wool). By reducing the size of the goat herds in this way, the herders expected to increase revenues while reducing pressure on the grassland. As project discussions began, different opinions emerged on priorities for the use of project funds, and attention began to shift towards the process for the community members to work together. Up to September 2009, the following activities were conducted in the Beizifu community and by line agencies:

- Various stakeholders related to pasture management consulted

- Biogas piloting and extension conducted

- Shed feeding facility improved

- Trainings and study tour conducted

- Beizifu Ke’erqin Pasture Protection and Management Association (community initiative) established in September 2008

- Participatory pasture management planning

- Water saving facility installed at farming land

- Mongolian cultural activities became an important part of the Association’s program

- Householder-based enterprises promotion

- Environmental education for children and schools

- Seasonal grazing planning and pasture restoration action

- Community-owned Pasture Guards Team established in partnership with Ke’erqin NNR

- Participatory monitoring of pasture restoration

- Farmer’s cooperative (on pig raising, biogas, farming, pasture, sheep raising, etc.)

- Community-based revolving fund (under the Association) established in 2008 and expanded at the beginning of 2009

At the time the Association was established, the action generated much interest and support from the county and township government and various agencies at both governmental levels. An empty classroom in a village school (the children are now educated at the town or county levels) was converted into a community center and association office with various awareness-raising materials about protecting the grassland on the walls, and a rather imposing list of Association regulations. Yet during this time, the community members gained actual experience with the economic activities supported by the project (the Association, for example, became the entity that could manage the revolving loan funds, and maximize benefits for their use – perhaps also to help with initiation of community enterprises such as processing of local dairy products or soya bean curd production). The Association has not provided any project money for converting family herds to cashmere goats, but has successfully encouraged some families to do so with their own resources; this activity was set aside as only marginally suited to developing collective activity and a cooperative spirit within the community. They came to regard maintaining their culture as an important aspect of community development, and started a women’s dancing group and an instrumental/singing group. They also started to understand the potential for cooperative action on such essential issues as grassland management and livestock management. For example, they established a team to investigate the problem of over-grazing and pasture degradation, and saw the complexity of the problem as well as the great benefits involved if they could reduce the number of intruders and external grazers on the lands of the community.

The Association was joined voluntarily by 67 households out of 223 in the Beizifu community, and grew to 134 households by August 2009. The Association’s leadership and members, as they gain a clearer understanding of the potential benefits of the Association, need opportunities to learn more about successfully managing and developing their Association, through outside expert advice and also by visiting other successful cooperatives within the grassland region.

These initiatives have been facilitated by Ke’erqin NNR with their best efforts. The reserve considered that resolving the conflict between conservation and development needs to be a substantial issue. Through project activities during the past three years, however, the reserve leadership and technical staff have realized the strong potential for community-based development to enhance resource protection and use while enabling the reserve to meet its conservation objectives in partnership with local communities.

3. REFLECTIONS FROM IDENTIFYING INTERVENTIONS

3.1 Objective Strategy and operational strategy

We aimed to interpret the livelihoods of local people and management of sustainable wetland resources in theoretical terms; and to strive to seek one method and approach for achieving a harmonious balance between the sustainable management of wetland resources and the subsistence activities of local people on the basis of an established wetland resources management regime. However, when it comes to the real world, this is not an easy task. We do not consider the arrangement of activities for community involvement programs based on livelihoods as the starting point, but rather wetland management activities as the starting point. This is an either-or choice, in which it is difficult to achieve the best of both worlds, and the choice has to be made.

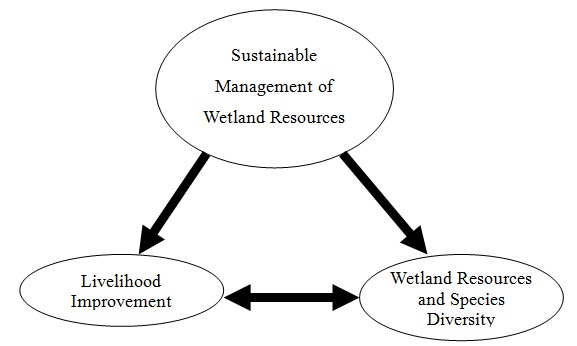

Researchers and reserve staff engaged in natural resources management would automatically design the project framework from the perspective of the sustainable management of wetland resources, as shown in Fig. 2. However, since the community participates in wetland management, it cannot become a simple community development or poverty alleviation programme, and Fig. 2 can be used as a basic conceptual framework for the sustainable management of wetland resources and conservation of biological diversity.

Figure 2 Conceptual Framework for Community Participation in Wetland ResourceManagement Programmes

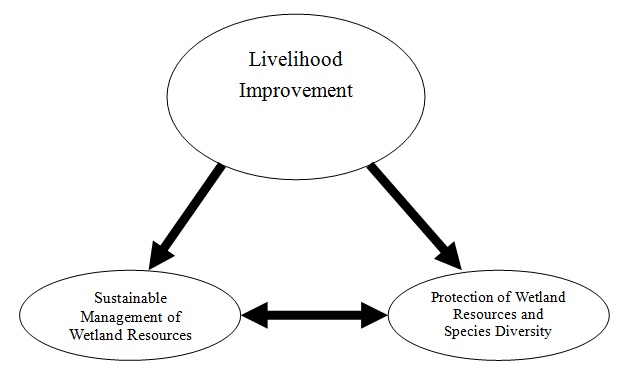

The above-mentioned conceptual framework needs to be transformed into a practical operational framework. It needs to establish preferred starting points for problem consideration in relation to the livelihood improvement of local people, as shown in Fig. 3. In other words, it needs to discuss how to resolve the problem of sustainable management of wetland resources and conservation of biological diversity based on the livelihood improvement of local people.

Figure 3 Operational Framework for Community Participation in Wetland Resource Management Programmes

As for the practical experience in Ke’erqin NNR, if the local communities could get more space to maneuver from government agencies, sustainable wetland resources management and biodiversity conservation would be better integrated into the proposed development programs that are currently putting most energy into livelihood improvement activities such as livestock raising, etc. After 2007, the researchers and reserve staff spent much time communicating and living together with the local people in the Beizifu community, jointly analyzed problems relating to the management of wetland resources with them, and gaining an understanding of the complicated relationship between their livelihoods and the wetland resources. This provided the basis for developing community livelihood programmes related to wetland resource management and the conservation of biological diversity, such as seasonal grazing planning and pasture restoration action, establishment of a community-owned pasture guard team in partnership with Ke’erqin NNR, and participatory monitoring of pasture restoration.

The above experiences were informative in regards to two issues. First, sustainable resource management needs to exceed its currently recognized scope, beyond simply maintaining the relative stability of ecosystem structure and functions and the continuity of natural ecological processes, to a more holistic concept of also protecting the related economy, society and culture. Specifically, sustainable resource management supports ecological sustainability; economics, social justice, multiculturalism, acceptability and well-behaved social construction are its life-force (Qian et al. 2008). Secondly, it cannot endorse rapid and flexible PRA as an adequate approach. This method only provides a tool for establishing mutual understanding between the researchers and the community. Thus, time must be invested to authentically develop programmes which are of intrinsic value. It was possible to generate valuable community development intervention programmes by improving understanding and consensus through interdependent learning between the villagers and reserve staff.

3.2 Orientation and objective model

In early 2009, we defined the Beizifu community as an “Integrated Environment-friendly Development Model”. After 2.5 years of work, we proposed that the GEF project should intervene to move towards a vision of the kind of village Beizifu should become. It is usually expected that when developing such a program, we must inform governors before receiving funds, so as to obtain resources for development intervention. We often got bogged down in the management conflicts. Based on the development intervention concept, we could only inform the project examining and approving body that the intervention direction of the Beizifu community project is correct, but were asked to provide detailed information on the “what, why, how and when” of project implementation. At the same time, community cadres and staff of the Protected Area Authority were already very accustomed to this way of thinking, even though they understood that the project was out of the control of project managers after its approval.

Rural development conducts social capacity building through the negotiations and efforts of different social actors. These social actors include: government organizations, farmers and farmer organizations, protected areas, universities and research institutes, etc. Different social actors hold different types and levels of resources, follow different principles of interest and value, and have different abilities. Different interpretations of development intervention by these actors and the interactions between them lead to diversification of development interventions (Long 2001; Liu 2006). Our approach aimed to promote diversity. We should not conclude the project failed simply because the realized community intervention was not the goal we expected to achieve. During the Beizifu community intervention, as the main decision-makers, we constantly reminded decision-makers involved in community project design that the most important thing is to find the direction of intervention, and that the specific development interventions can be left to grassroots actors. In the last three years, the decision-makers participating in the Beizifu community development intervention gradually understood this concept, which was an important success factor.

3.3 Identifying project activities towards community-based resource management

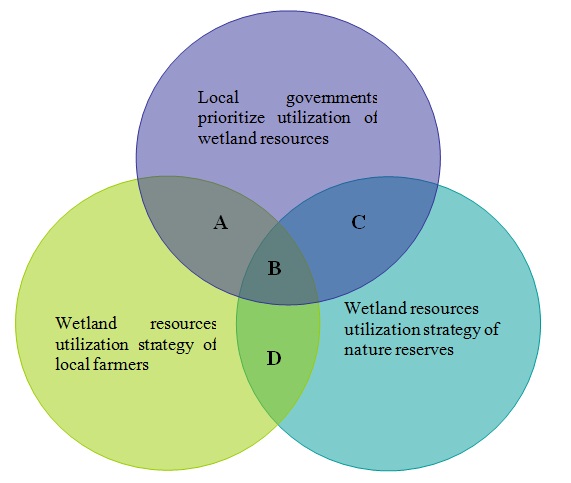

Figure 4 shows an ideal basis for development interventions on wetland management (Qian et al., 2008). First, we need to seek the common points of the development strategy of local government, the development strategy of rural households, and the acceptable utilization strategy for wetland resources. As the model in Figure 3 suggests, a viable strategy for the sustainable management of wetland resources consists of the overlapping sectors of local government, protected areas and local community households, as long as the technology employed has economic feasibility. In reality, local governments have long dominated local development; at least they have indisputably dominant rights in economic development. For more than 20 years, farmers could only avoid or resist if they did not like the Government’s development strategy, while the management bodies of protected areas made little contribution to development strategies and specific measures. Now it is necessary to promote the participation of protected area staff in development strategies and specific measures in order to achieve the conservation of biological diversity and sustainable use of wetlands.

Figure 4 Analysis of Community Development Project in Wetland Reservation

Secondly, considering feasible technology, the available area will be more limited, as shown in Table 1, which required us to conduct a more careful investigation and study, a more comprehensive analysis and multiple arguments. It should be noted that to design a suitable intervention and to promote the sustainable management of wetlands within the protected area and its surrounding villages is more difficult than an average development project, requiring a more meticulous feasibility study. The general practice is to first carry out a comprehensive analysis of the development strategy of local government and the interest of related protected areas, then to conduct deep assessments of families in the community to understand their problems, challenges and strategies in development, and to determine a possible strategy which can cover the development strategies of local governments and acceptable management techniques and measures for protected areas.

Table 1 Consideration of feasibility for development projects

The local government and local farmers accept, but the protected area authority does not accept, technically unfeasibleThree parties accept, but technically unfeasibleThe government and protected area authority accept, local farmers do not support, technically unfeasibleProtected area authority and local farmers accept, but the government does not support, technically unfeasible

Thirdly, the complicated social factors increase the complexity of project selection. Farmers in rural communities are not homogeneous: there are all kinds of families in a village. Residents of the Beizifu community emigrated from other places one after another over the last 300 years, with some families having more than three hundred years of history, while others have only thirty years. Some families divide up, and are in heavy debt due to weddings and the buildings of new houses; some have a sick main labor force; some have to spend large sums of money for children to go to university; some have disabled or mentally retarded members. Every family wants to do different things and faces different practical difficulties. It is difficult for grassroots governments to find a development measure and action which can easily satisfy all families. Coupled with the long-term impact of a planned economy, it is difficult for grassroots governments to adapt to such a huge change in rural communities, lacking the work experience in rural communities under a market economy. Another constraint is that the capacity of some rural cadres is questionable; they usually do not have the time or the patience for field investigation and study. Protected area staff members are generally committed to their work, often involving some self-sacrifice. But they have their own families, clans, and other social networks. They also have personal plans for family development, so their behaviours are promoted and restricted by the social networks. All these factors influence their views on wetland management to various degrees. These views objectively reflect the interest of individual members, families, clans and other social networks of protected area staff members, as well as their knowledge and life experience. In real life, to promote community co-management work, it is necessary to empower the authority of the community in managing its natural resources. Even if the leadership of protected areas recognizes this trend, the average employees do not necessarily agree. The loss of power means loss of face, and loss of access to benefit. It also goes against their need to protect their own social networks.

3.4 Entering the community

In an era when China’s social economy is changing rapidly, the farmers in the Beizifu community are being marginalized. There are various contradictions and conflicts between farmers and other farmers, farmers and the community committee and Party branch, villages and other villages, villages and grassroots governments, and villages and protected areas. These are the biggest problems facing Chinese farmers in developing their communities. Villagers view people from outside with wariness and hostility. The biggest problem the project faced was how to remodel the community’s understanding of protected area staff, local government staff and project experts.

We introduced a concept of an entry project to cope with the above situation. Usually long processes are involved to reach project approval, from project identification, proposal formulation, application and approval by many levels of authorities, fund transfer processing, which usually requires one more year, in particular for the first project for the Beizifu community. Meanwhile in the real world, the nature of the community and participating households may change, and the farmers’ interests may also shift. These usually create additional conflicts between the local government and the local community. Thus, during the first visit for developing integrated community development planning, we clearly stated that the first project proposed by the Beizifu community would be approved with only two conditions, agreed to by the majority of community, and less than 50,000 yuan in total budget. This project would be considered as a gift to the community for developing trust between the project staff, the community and the local government. A community-based revolving fund was selected by the community as an entry project.

3.5 Implementation

Local officials and community heads are used to implementing projects through top-down processes. Thus a critical issue was how to change the attitudes and behaviours of all actors, including local officials, community heads, and officials from the Ke’erqin Nature Reserve involved in the implementation process.

China does not lack the idea of participatory processes and practices either in ancient or contemporary history (Liu, 1999). Based on the experiences in the Beizifu community, change of individual behaviour and attitude is the most difficult part of promulgating community-based natural resource management practices. Outsiders need to recognize ‘the knowledge and skills of the community people’, and to collaborate with the local people, to be ‘learners’ rather than ‘leaders’ or ‘alms givers’. Many local officials still doubt the capability of the local people (Liu et al., 2004).

In the past three years, the community has demonstrated its capacity to implement its project towards the sustainable use of natural resources. Some officials have learned from this process and their attitudes and behaviours have gradually changed. However it is still one of the major barriers to project implementation.

3.6 Monitoring and evaluation

Although it is an important stage in the project cycle, very little knowledge has been gained on how to evaluate the intervention. However, we can summarize the achievements according to the opinions gathered from all the actors in the process. During the three-year intervention, the Beizifu community has been unified, the goat herds have been downsized to about two-thirds of former numbers, and the herders expected to increase their revenues while reducing pressure on the grassland. The Association has not provided any project money for converting family herds to cashmere goats, but has successfully encouraged some families to do so using their own resources. This activity was set aside as only marginally suited to developing collective activity and a cooperative spirit within the community. The villagers came to regard maintaining their culture as an important aspect of community development, and started a women’s dancing group and a musical instruments/singing group. They started to understand the potential for cooperative action on such essential issues as grassland management and livestock management. For example, they established a team to investigate the problem of over-grazing and pasture degradation, and saw the complexity of the problem as well as the great benefits that could be realized if they could reduce the number of intruders and external grazers on the lands of the community. In short, the progress made in the community has testified to the possibility of harmonization of rural development and environmental protection (or biodiversity conversation).

4. REFLECTION AND CONCLUSIONS

4.1 Development Intervention

Planned development interventions do not always achieve their expected direct outcomes. Reviewing the two decades of experience on planned interventions towards co-management schemes for biodiversity conservation, a rather mechanical model of the relationship between projects, implementation and outcomes has been mostly espoused. It is necessary to re-conceptualize the notion of an intervention as “an ongoing socially constructed and negotiated process, not simply as the execution of an already-specified plan of action with expected outcomes” (Long, 2001). Intervention is made up of a complicated set of processes, which involve the reinterpretation or transformation of intervention action during the implementation process. Therefore, there is no straight line from action to outcomes. In fact, outcomes may be the result of factors not directly linked to the particular implementation program. Local governments and communities always find sufficient space for formulating and pursuing their own ‘development projects’, that often clash with the interests of upper level government institutions; in particular, those at the highest level and most socially distant. Implementation should, then, be viewed as a transaction process involving negotiation over goals and means between actors with conflicting or diverging interests, and not simply as the execution of a particular policy (Warwick, 1982). We must also take account of the diverse ways in which individuals and their households organize themselves, individually and collectively, in the face of planned interventions promoted by ‘higher’ authorities, such as governments and international development organizations. The strategies they devise and the types of interaction that evolve between them and the various intervening parties shape the nature and outcomes of the interventions. In this way, ‘external’ factors become ‘internalized’ and come to mean different things to the different interest groups or to the different individual actors involved, whether they be implementers, clients or bystanders.

4.2 Unification of the Community

Since collectivization was introduced in rural areas, public services have disappeared. In production, villagers must face the market by themselves. They have been totally dominated in terms of agricultural production technology, agricultural supplies, and marketing. In Ke’erqin, there is continual pressure from three different sides on the villagers’ land-use decision-making space:

1)Market. The role of the market is giving villagers increasing impact. Villagers have to rely on the market to make production decisions, and commercial rates of these agricultural productions are increasing. Villagers also depend more and more on the market. Green revolution technology has also had a growing influence on the production behavior of villagers. It has led farmers to be more dependent on agencies which provide credit, seeds and fertilizers, and farmers have to sell their agricultural products to repay these debts. And these service agencies usually retain a high margin of profitability. Diesel supply serves as a good example of this as villagers need irrigation to achieve agricultural production, and the associated costs are an important part of overall production costs and fertilizer, one of which is that farmers buy fertilizer on credit from private agricultural enterprises before production. When the farmers harvest their crops, they have to pay 140% of the amount received on credit before production. Villagers can get loans from credit associations, but they need a mortgage to receive a loan, and even if there is a mortgage, they cannot get a loan when they are most in need of money. The interest rates on loans to farmers are high, equivalent to an annual interest rate of about 20%.

2)Policy. In recent years, the government has been enacting various policies, such as a prohibition on grazing, enclosures, etc. The use of natural resources by villagers has been limited to a certain extent by the establishment of Ke’erqin NNR in the Inner Mongolia, a natural forest protection project and other such activities.

3)The government’s development interventions. For example, in Ke’erqin Youyi Zhongqi, the local government developed the silkworm industry in 2008, including a village in the Ke’erqin protected area. The Beizifu Community opened grasslands and planted mulberry trees under the leadership of the local government. While this policy was supported by the people, they were in fact supporting the opportunity to open up new farmland instead of planting mulberry trees, for there are prohibitions on creating new farmland on grassland areas. From the people’s point of view, it does not matter if the mulberry survives; what they care about is the fact that the grassland has already been opened up for farming. When the plan for mulberry cultivation fails, switching to the cultivation of other crops will become a matter of course.

The living space of the community is also being compressed. Community leaders are under increased pressure from higher authorities to improve management practices, but usually without the concrete support required to do so. To make things worse, the higher authorities and staff of protected areas have to take over some of the power of the community leadership, because their own utilization and distribution power is declining due to the policies and interventions introduced by governments at higher levels. Some even participate in the business of ‘selling’ (contracting out) natural resources, a practice carried out by some community leaders to accommodate social pressures or create financial impetus.

Another aspect is that, exposed to the rapidly changing outside world and the widening of employment opportunities and channels, communities are faced with more and more choices. The big contrast between the local communities and the outside world encourages increasing numbers of young people to leave their communities in order to seek new livelihoods and ways of life. This, to a certain extent, promotes the disintegration of communities.

The disintegration of communities has generated many problems. As a result of a weakening of the community’s collective consciousness, there has been a lack of public awareness and a weakened sense of community by progressively more people, because social networks tend to be established with the neighbourhood, family and external society. Everyone focuses on their own matters and there is a serious lack of community production and living services. Individual farmers face the market alone, and purchase their own agricultural resources. It is not possible to organize water facilities, and there is a lack of public cultural activities. he direction of intervention within China’s rural development is to rebuild the consciousness of the community and develop a sense of ownership. It is also the key to rebuilding communities like Beizifu.

In 2007, China estimated the difficulty and long-term characteristics of re-modelling communities. By promoting communities to build an “invisible” and “visible (physical) space” to establish a common platform, it has made it possible for villagers to participate in the management of natural resources, as well as decision-making for community development. The “invisible space” includes a recreational team, security team, grassland Protection Association, and various other types of groups. The ‘visible space’ includes a community center and a community-based revolving fund group. An important indication of progress in the community’s remodelling process was the 2009 Women’s Day. The village organized a reunion for women, which involved the voluntary participation of almost all the village women in the activities. The village cadres had not expected that so many would be willing to participate. During the implementation of the community project, the village cadres gradually established the role of village elite, and villagers demonstrated their enthusiasm for the 2009 village election. The main participants of community project were chosen for the newly elected village leadership. Our three-year experience with the Beizifu community proved that if outsiders treat the members of a community with sincerity, listen to their concerns, and respect their decisions, they will gradually grow to trust outsiders, and will also become organized.

4.3 Power of traditional culture

Culture plays an inherently strong role in community development. The majority of community projects focus solely on activities that lead farmers to become wealthier, or facilitate the production and livelihoods of the people through the building of bridges, roads, gas supply, etc., while ignoring the potential of culture. In this project, we deliberately emphasized projects which can unite and mobilize communities, attempted to work with local natural resource management of wetlands, and combined these with local biodiversity conservation. In Beizifu, we saw the potential influence of culture on development.

Culture remodeling is a long-term dynamic process. In some protected areas, or Forestry Bureaus, a bureaucratic culture has been created, which consists of avoiding trouble whenever possible and bullying the weak and small. This goes against the precepts that: “nature and men are one“, or “men and birds under the same blue sky“. There is a long and difficult path towards encouraging communities to love birds and respect nature, while resisting the bad behavior of a few internal and external individuals.

China is faced with fierce conflicts between traditional and modern civilization, agricultural and nomadic lifestyles, and shifting modes of cultivation. We must realize that China is undergoing social change and may not return to a traditional form of civilization. The social conflicts, environmental degradation, public confusion and social disorder brought by cultural fragmentation will become increasingly obvious. Therefore, China badly needs new concepts for connecting modern and traditional ways of life, and for building a new Chinese culture based on traditional values and China’s rich and varied natural environment, thereby achieving a new harmony between nature and culture.

4.4 Centralization or decentralization

Policy on pasture and wetland resources has shifted frequently since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Each shift has always placed local communities on the losing side in terms of access to resources. During its first 30 years, China was in a period of centralization and collectivization, followed by 30 years of decentralization and de-collectivization. Somewhat paradoxically, however, regardless of whether collectivization or de-collectivization prevailed, the outcome has always been the same: resource degradation. This at least part of the reason why China finally ended up undertaking massive and largely centralized interventions in terms of pasture protection, grazing prohibitions, and caged raising of cattle and sheep. This suggests that the best policy for the restoration of natural resources would be through rebuilding the strong link between local people and their resources.

There have been dramatic changes over the last 60 years in the interrelations between people, communities, and resources as reflected in changes within the macro-political, economic and social contexts, as well as changes at the micro level in terms of power relations, knowledge, and livelihood struggles. Frequent mutations in the macro and micro contexts have resulted in concomitant shifts in resource management and land use. This has brought at least one negative consequence, namely that short-term planning has caused the loss of local communities’ endogenous resource management practices and possibly undermined the relatively harmonious power relationships that existed between the different actors in the villages (Liu, 2006).

Since 2003, the local government has applied a policy of zero grazing to offset the trends in degradation of pasture resources. Garrett Hardin’s “The Tragedy of the Commons” has stimulated China’s policy makers to try to put a stop to de-collectivization and privatization, and to prevent selfish individuals from overusing common resources. However, there is much more to the issue than that. Resource use and management is a critical arena for struggle and conflict between stakeholders (Liu, 2006). Access to trees and their products galvanizes the interests of both outside groups – the government and authoritative non-government actors – and inside groups – community people. The fundamental question we should ask is whether local knowledge systems, power structures, and cultures will be able to coexist and integrate in the face of external capital invasion and privatization (Baumann, 1998).

REFERENCES

Baumann P.C. 1998. Historical Evidence on the Incidence and Role of Common Property Regimes in the Indian Himalayas. Environmental History, 3, 4: 323-342.

Gilmore T., Krantz J., and Ramirez R. 1986. Action Based Modes of Inquiry and the Host-Researcher Relationship. Consultation 5.3 (Fall 1986): 161.

Liu J. 1999. Farmer’s decision is best-at least second best. Participatory development in China: review and prospects. Forests, Trees and People NEWSLETTER. Vol. 38: 13-20.

Liu J. 2006. Forests in the mist. Wageningen University and Research. PhD dissertation.

Liu J., Yuan J. 2004. Enhancing community participation: participatory forestry management in China. Pp. 93-138 In: Plummer J and Taylor J. (eds) Community Participation in China – issues and processes for capacity building. Earthscan, London.

Long, N. 2001. Creating Space for Change: A Perspective on the Sociology of Development. In: Long N. Development Sociology: Actor Perspectives. London: Routledge.

Qian F, Liu J, Jiang H. Zhao L. and Wu X. 2008. Community Participation in Wetland Management. China’s Science and Technology Publishing House. Beijing. (In Chinese).

Struthers, R. 2001. Conducting Sacred Research: An Indigenous Experience. Wicazo Sa Review 16 (1):125-133.

Susman, GI. 1983. Action Research. pp.95-113 In: Morgan G. (Ed.) A Socio-technical Systems Perspective. London: Sage Publications.

Warwick, D. 1982. Bitter pills: population policies and their implementation in development countries. Cambridge University Press.