Recovery of Mouthless Crab (Cardisoma crassum) Populations in Mangrove Forests of the Chone River Estuary (Ecuador)

28.08.2014

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Foundation for Research and Social Development (FIDES)

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

28/08/2014

-

REGION :

-

South America

-

COUNTRY :

-

Ecuador

-

SUMMARY :

-

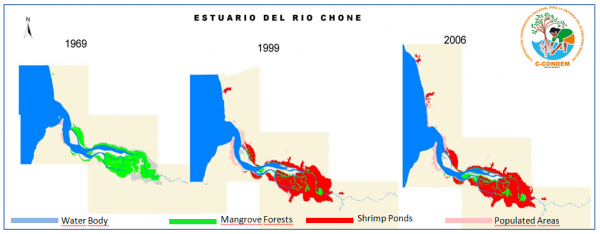

Mangroves are considered one of the world's most productive ecosystems (RAMSAR Convention). In addition to their significant ecological role, mangrove habitats fulfill important economic, cultural, and social functions for the various communities settled on the banks of estuaries. Despite the environmental, social, economic and cultural importance, and the existence of a legal framework for protection, more than 80% of the mangroves in Chone River Estuary have been destroyed by the shrimp industry. This destruction has caused deteriorated living conditions in families that have lived off of the ecosystem for generations, mainly due to the decline and loss of species that have been part of local community’s food security. The FIDES Foundation’s intervention with families dedicated to fishing and gathering allows the generation of alternative livelihoods for mangrove communities of Manabí through the protection and sustainable use of mangrove resources. An important example of this is the recovery of the Mouthless crab in situ, in a process that combines ancestral knowledge and practices with new technical knowledge. The case study shows an ongoing pilot project that is generating positive results for the recovery of the mouthless crab.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Mangrove ecosystem, Mouthless crab, Local community, Livelihood

-

AUTHOR:

-

Maria Dolores Vera Economist, Masters in Agricultural Economics and Rural Development Mrs. Vera comes from a local rural community in Ecuador (South America) and works at the Foundation for Research and Social Development (FIDES). Her experience includes working with local rural communities in strengthening community organizations and economic activities, protected areas management, and mangrove ecosystem restoration. (Email: mdoloresvera@hotmail.com) Gina Napa: As a women leader to the Ecuadorian people living in mangrove communities, Mrs. Napa works in community tourism, and promotes organizational strengthening and mangrove restoration activities in communities. At present, she is President of the National Coordinating Corporation for the Defense of Mangrove Ecosystems, which is a network comprised of 100 organizations of artisanal fishermen, gatherers and members of the Council of the International Mangrove Network.