The importance of the Farmers Field School approach: A case study – Farmers Field School practical training programs, Vietnam

22.12.2015

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Social Policy Ecology Research Institute (SPERI)

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

22/12/2015

-

REGION :

-

South-eastern Asia

-

COUNTRY :

-

Viet Nam and Lao P.D.R.

-

SUMMARY :

-

Farmers Field School (FFS) is a group-based learning process for achieving farmer empowerment, community development and education of eco-friendly farming methods. In Vietnam, the Social Policy Ecology Research Institute (SPERI) started a network of FFSs around end of 2006 to address numerous issues: the losses of traditional knowledge from previous generations in the upland landscapes; the lack of access-to-education for the disadvantaged ethnic minority youths; the need to secure locally situated knowledge and practices; whilst also increasing farmers-to-farmers learning in the upland regions. This paper provides detailed information of the FFS education program of SPERI, specifically at the three core hands-on training programs: forest regeneration/conservation; ecological farming practices and the nursery program. The focus on learning/knowledge generation and knowledge enhancement (learning from experiences/real exposures, and also from failures) from the FFS-SPERI approach could provide a useful contribution to Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) management, restoration of degraded forest landscape, and conservation of ecological system and biodiversity.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Farmers Field School approach, Training programs, Forest landscape management, Ecological farming practices, Indigenous minority students, Learning experiences

-

AUTHOR:

-

Kien To Dang, SPERI/CENDI

-

LINK:

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Introduction

*This case study was first published in the Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review, Vol. 1.

The introduction of FFS approach to organic vegetables farmers in Vietnam occurred in the early 1990s. During the period 2000 to 2009 FFS was adopted largely through agricultural project supported by international donor such as Agricultural Development Denmark Asia (ADDA). ADDA projects used the FFS structure to provide farmers with the technical knowledge to enable them to increase their income through growing various short-term crops.

The Social Policy Ecology Research Institute (SPERI), Vietnam, also used the FFS approach for slightly different reasons. SPERI witnessed that many minority youths lack access to an education that incorporates minorities’ culture, particular way of thinking, and wisdom. At the same time ethnic youths do not have the financial resources to access to education. Deforestation in many areas of Vietnam and Lao P.D.R., especially the upland, is a serious issue (FAO 2011b) that results in increased poverty (Mellor & Desai 1996), increased food insecurity (FAO 2011a) and also landscape/ecosystem’s degradation. In the context of an increasing urbanized and industrialized country, many minorities find it very hard to maintain their way of life (Baulch et al. 2007; Lanh 2009).

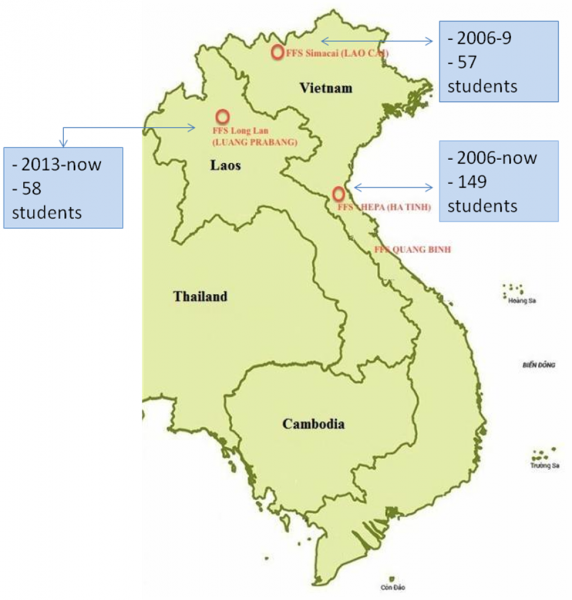

The name Farmers Field School itself, by SPERI’s adoption, reflects a dream on how to approach and facilitate ethnic minorities in an ‘easy-to-understand, simple and low-cost’ entry-point. FFS works with ethnic minorities to help improve their lives and landscapes by using parts of their own knowledge and culture. By establishing and running FFSs in remote mountainous upland areas, SPERI hopes to contribute to empowerment and enhancing practical knowledge on how to address the various issues mentioned. SPERI has a network of four active FFSs across Lao Cai, Ha Tinh, and Quang Binh provinces of Vietnam, and one extending to Luang Prabang province, Lao P.D.R. The FFSs are located at remote upland areas where limited infrastructure and rough mountainous terrain are present.

Figure 1: Map of the network of four Farmers Field Schools in Vietnam and Lao P.D.R. (SPERI, 2015).

SPERI facilitates hands-on trainings through FFS’s. The curriculum is composed of various topics that are critical for securing and recovering the integrity of forests and associated ecosystems in the target areas, including forest regeneration/conservation in the upper and mid elevations, ecological farming practices in the mid and lower zones and a nursery program in the lowest land. SPERI refers to these combinatory actions undertaken simultaneously in a landscape as our operational definition of ‘landscape approach’. The aim of the curriculum is to provide skills useful for maintaining traditional knowledge and ecological services, restoring degraded forest landscape, as well as conserving species and biodiversity values. Over years of operation, results have indicated an improved management of SEPLS. The FFS-SPERI approach could be a useful contribution to SEPLS management, restoration of degraded forest landscape, and conservation of ecological systems and biodiversity. In the long-term, FFS’s should demonstrate harmonious interactions between humans and nature within the Satoyama Initiative framework.

Method

Strategies

FFS-SPERI strategies are applied to nurture and train one or more groups of ethnic youths from varied upland landscapes and to build a strong network amongst them in varied scales (i.e. individual farm houses, community farms and regional farms). Students are selected from villages by community members and also by SPERI. The selection process targets those who wish to learn but do not have the finances, have the land area at home for later application, have a strong wish to maintain ethnic pride and community values or are recommended by family, village elders or the local authority. FFS facilitates and strengthens the linkages between ethnic minority youths and senior farmers by inviting these senior farmers to be direct teachers to the younger ones in training programs. This helps promote sharing of traditional knowledge and experiences. Collective thoughts and actions among them are also sought to look for local solutions to improve local community land use planning and resources management.

Training methodology

FFS-SPERI training methodology is based on ‘learning-by-doing’ (1). This methodology was introduced by SPERI in 2006 and is currently in use. After students identify their needs and concerns, the FFS training programs are set up according to these students’ needs. Long courses are often one-to-two years; short courses are often one-to-two weeks, although in some situations courses are three months long. The usual hours for learning are about 5 hours average per day. Depending on theme or topic, the shortest class would be 3 hours. Depending on season, the length of classes may reach an entire day, with two hours in the morning spent for classes and three-to-four hours in the afternoon for practical sessions. The number of hours and frequency of classes very much follow the natural calendar of the crops and plants. Every week, there is one community day that has no class and one question-and-answer session, where students can voice questions from observations and findings of interesting things from nature or regarding practical work and engage in shared seeking of solutions together with friends and staff. All the training programs’ topics are designed and operated by re-creating a place similar to the students’ home landscapes. For the ethnic minority youths, it is essential to build curriculums that contain certain similarities to the environment where they came from, in order to garner their interest and provide learning connected with their background (instead of disconnected). This appears to be a crucial point for students to relate better to knowledge, and for the knowledge to be better received and more easily practiced by the students.

Learning environment

The FFS-SPERI practical learning environment often includes actual farms and forests. Providing students with access to real farms of manageable size for running, and chances for rotationally taking on the role of management, as well as learning sessions within the forest areas, help students learn more quickly and relate more easily to the FFS learning environment and think about its applicability to their home villages. Further, students participate in field trips in-and-out of FFS environments which are also helpful to increase their exposure to new situations, and hence knowledge generation. Questions are often raised during the trips that allow students to relate what they have learnt and seen to issues in their home communities. Other key learning environments provided at FFS are study tours to various pilot sites, either successful pilots (e.g. good community forest management models, small organic farms) or failed examples (e.g. degraded sites or conventional agricultural farms).

Knowledge enhancement

In order to enhance knowledge in the wider community, study tours for external stakeholders (e.g. students, farmers association, governmental officials and nongovernmental organizations) from various regions are invited to visit the FFS’s. Knowledge exchange commonly occurs between scientists and traditional knowledge holders, as well as between international volunteers and local students. Knowledge exchange also occurs among policy makers, agricultural extension officers, practitioners, farmers, community leaders, elders and the youths. This allows students to improve their level of understanding and engage with different actors to facilitate changes.

The following sections provide details on the three training programs.

Training program on forest conservation/regeneration

The training program on forest conservation and regeneration plays a key role in raising awareness on how to address forest degradation. All FFS sites are located within forest areas. The training program is designed to involve courses and also on-the-ground activities within the forest areas. Studying and observing forest ecology, the relationship between forest and fauna ecology, and forest health and landscape patterns in the upper catchment have helped students understand the multiple values obtained from forests, and hence realize the importance of conserving forests. The program also includes training on how degraded and regenerated landscapes influence ecosystem services, such as watershed function, water generation for downstream agricultural production, and other cultural/aesthetic values.

Figure 2: Students conducting a practical learning session in the forests (Photo by FFS-HEPA, 2011).

Figure 3: Students studying ecology of a species from a Sach minority herbalist (Photo by FFS-HEPA, 2013).

Practical learning sessions teach students how to identify forest species with daily-use values, such as edible plants and herbal medicinal plants. Elders from the students’ villages, female herbalists, and also botanists are invited to teach. Forest vegetables provide added-nutrition and medicinal plants cure illnesses. This helps students to build a stronger connection with the forests and benefits their daily lives. After identification of edible and herbal plants, students organize trips to the forest to collect these plants. The plants are then propagated at the students’ experimental farms or at the nurseries.

In the upper part of all FFS sites, an area is designated for strict protection. The area includes a sacred Banyan tree and a special rock. A ritual ceremony to greet the Forest Spirit – located in the Banyan tree – has been organized monthly. Incorporating the spiritual values of the forests into the learning process is important for behavioural change. Conservation messages such as, “if anyone cuts the sacred trees it could affect the spirits, and they might get sick”, have been transferred to students and everyone else to promote conservation. The monthly ritual ceremony teaches students and visitors alike the importance of protecting and nurturing nature. No damages, violation and wrong-doings are acceptable in this upper part.

Another key part of the training program on forest conservation is the organization of weekly forest patrols in order to prevent illegal logging and wildlife trapping. Often a group of three to five students has been organized to patrol the forest. This weekly or monthly activity is integrated into the program as an important part of assessing the study results. Whilst patrolling the forest, students also learn how to identify local species of value mother trees and to develop regeneration strategies. Forest patrolling teams also invite people from the border army and nearby local community. Strong collaboration amongst the FFS, students, and local authorities including provincial and district authorities, border army officers, the watershed management authority, and the neighbourhood community, has been established.

Training program on ecological farming practices

Given that the FFS training program takes the landscape approach, it is crucial to not only train in protecting the upper part but also nurture good practices in the middle hill followed by the lower zones through appropriate farming and management practices. The training program educates students on the ecological farming system as a system approach, as well as provides specific ecological farming skills.

Figure 4: Students and elders observing nature and recording (Photo by FFS-HEPA, 2012).

The ecological farming program is based on a combination of permaculture and information gathered by SPERI from indigenous minority communities (3), based on the indigenous minority communities’ values – beliefs, ethics, natural patterns, local knowledge and wisdom towards nurturing nature. In 2005, permaculture was first introduced to SPERI’s farmers’ network (4). Permaculture highlights the meanings from the natural landscapes. This is illustrated by the need to maximize learning from nature and strive to leave the smallest footprints upon nature. The integration of this science and traditional knowledge from ethnic minorities has continued to develop. Ecological farming knowledge respects the landscape approach, and logically connects with the earlier forest conservation program. It is seen as a method to maintain all the natural nutrients from the forests in the upper part to be re-used on the farms and the nurseries located in the mid to lower hills.

Ecological farming training is delivered on actual farms (5). These farming areas have been carefully designed to follow the natural patterns of landscapes to maximize ecological function and resilience. Students can learn-by-doing on the allocated farm. The size of the allocated farm is often just less than one hectare. Students share one farm in a group of three to four people. On the farms, they grow various crops, raise animals, and also run trial research. Students can experiment to learn which ways plants grow better, and/or combine plants-and-plants or plants-and-animals.

Specific ecological solutions have also been taught. The table below illustrates an example of a yearly eco-farm training program. Topics included are: erosion control through terracing systems, forest watershed management and patrolling, water management through banana circles and the reed bed system, waste management through banana circles, worm farms, 18-day compost, mulching, bio-fertilizer, natural soap, herbal tea, garden bed design, animal systems, animal silage, fruit trees, multi-functional plants, bio-gas, bio-char, handicrafts, and wood carpentry.

Table 1: An example of a yearly eco-farming training program (FFS-HEPA, 2013).

Besides specific skills, the training program also includes a theoretical approach focusing on the ecological returns of land and resource management and nurturing cultural beliefs whilst encouraging leadership skills and creative and critical thinking.

On a farm site, there are often three major activities: food production, animal raising, and housing and crafting. Although almost no vegetables come from outside the FFS’s, the current vegetable production is not sufficient. According to a recent estimate from Rào An’s farm output records, the minimum vegetable production to supply the Rào An farm area (in case around 10 people are eating there 3 times per day) is about 130 kg per month. 130 kg per month for 10 people is the estimated real harvest on average (929.9 kg/7 months = 132 kg/month), which is generally sufficient (Muijlwijk et al, 2014). FFS production of vegetables or any other organic produce is not exceeding internal demand hence it is insufficient to sell to consumers. At a few farms, students raise bees near the forest margin to collect natural honey.

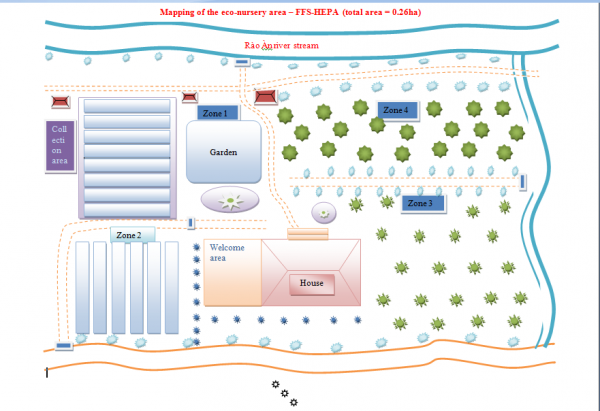

Training program on nurseries

The nurseries program of the FFS’s is also set up, often in the lowest area of the FFS terrain and near the forest edge (6). The nursery often has four main tasks. It nurses all the locally available native species to help forest regeneration and rehabilitation in degraded areas. It collects local species from various regions to nurse and builds up a seed bank for seed conservation. The nursery also links strongly with other eco-farm networks at the community and household levels. It also provides hands-on training courses for many student groups, farmers’ groups and anyone interested.

Figure 5: An example of the current area and zones at a nursery (FFS-HEPA, 2012).

The nursery has a collection of four types of tree plants: landscape trees (trees providing landscape function/ decoration), timber trees (trees providing hardwood, e.g. house poles, coffins), material trees (i.e. trees providing materials for roofing such as rattan, bamboo), and forest vegetables and others vegetables/herbs/flowers).

Figure 6: Students collecting seeds in the forest (Photo by FFS-HEPA, 2014).

Figure 7: A hands-on learning session with farmers at the nursery (Photo by FFS-HEPA, 2014).

Specific activities have taken place. First is the collection of seeds from the forest, largely mother trees and locally valuable pioneer species. Second is the nursing of these seeds into seedlings, small trees and matured trees good enough to replant in the degraded area within the FFS’s and also neighbourhood areas. Third is the testing of new sites for species. When other tree, flower, and vegetables seeds are brought in from other regions or countries, they are tested in the nursery to determine if they will grow well. New knowledge can be generated from these trials. However, work in collaboration with seed scientists, experts and botanical specialists, as well as traditional knowledge holders, is also being continued regarding the extension of this work and to what degree it is appropriate to avoid invasive alien species overtaking native species. Final the aim is to deliver this extension function to anyone interested.

Results

3.1. Number of students trained

Since 2006, SPERI FFS’s have educated more than 200 disadvantaged ethnic minority students with a high school equivalent degree conferred in Vietnam or Lao P.D.R. A few graduates received recognition from the Australian Permaculture Research Institute. Some graduates are now working to expand SPERI’s vision on ecological farming practices in the ASEAN region. Some chose to be mobile trainers to help with re-training others at household farms in Thailand, Myanmar, and Lao P.D.R. Many of the graduates got jobs as local agroforestry extension officers or are involved in gardening or forest groups within a village. Some graduates sought further education or chose a different career path.

| FFS courses included HEPA, Simacai sites and number of students |

| Long courses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Short courses |

|

|

Table 2: Number of students trained at Farmers Field Schools (SPERI, 2013).

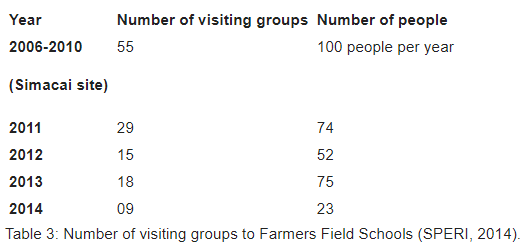

Number of visiting groups

FFS training programs have received various visitors including students and lecturers from other universities, international volunteers, experts and specialists, local authorities including high-level government officials, provincial and district authorities, functional offices, agencies, and farmers from many provinces to learn and share knowledge. In total, there have been nearly 200 visiting groups and thousands of people since 2006. The number of visiting groups has been decreasing primarily due to stricter border control regulation. A total number of 50 international volunteers have contributed to knowledge sharing and better management of forest landscape and ecological farming practices at all FFS sites.

Table 3: Number of visiting groups to Farmers Field Schools (SPERI, 2014).

Long-term results from forest conservation/regeneration program

As a result of continuous protection of the forests, the data has indicated a reduction of illegal logging cases over the years in the area. The number of trappings of animals/wildlife from the forests was also reduced. Since 2002, landslides have not reoccurred in the region due to more forest plantings and restoration/preservation has contributed to retain water level and also the soil surface structure.

| 2010-2013 | 2013-2014 | |

| Results from patrolling the forests | Found > 500 traps;

Captured 6 illegal loggers; 4 guns for illegal hunting; |

Captured 3 illegal loggers;

Captured 6 illegal logging cases without knowing who. |

Table 4: Results from forest patrolling from 2010 to 2014 (FFS-HEPA, 2014).

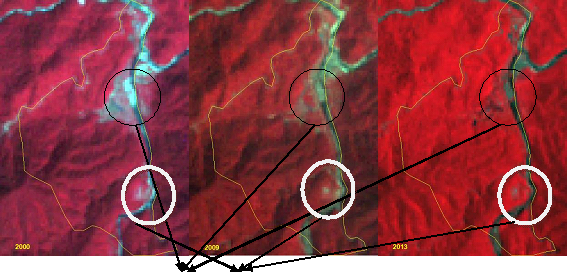

The program of forest conservation and regeneration is most outstanding at FFS-HEPA. The yellow boundary (polygon) indicates the total land area of FFS-HEPA. Forests conservation and regeneration have been proven through Landsat satellite images. The changes on satellite images reflect both actual on-the-ground efforts from forest patrolling and tree planting activities. These satellite images, when reflected as Normalized Differences in Vegetation Index (NDVI) values, indicate significant positive changes from 2000 to 2009, and recently in 2013 in the coverage of forested areas.

Figure 8: Two areas through images indicating significantly positive changes in forest coverage by on-the-ground forest protection and planting efforts (FFS-HEPA, 2013).

Mid-term results from ecological farming program

One of the interesting results from the ecological farming program is the number of students after graduation that continue working on promoting eco-farming practices in their communities. About 50 percent of the total graduates from FFS training programs have returned to their home communities to build ecological farming sites on small farms, and also engage in forest regeneration activities. About 10-15 percent of students have managed their farms close to eco-farming principles. This happens in both Vietnam and Lao P.D.R. About 30 percent of the graduates now have jobs as agricultural/forestry extension officers, or have taken on other formal responsibilities in local communities. About 20 percent of the graduates have proceeded to further education.

The other remarkable result is the extension of application of the banana circle, an important ecological solution to resolve household wastewater grey water and composting of organic waste materials. Banana circles have five to seven banana trees – arranged in a ring-like structure. The banana circle contains further wastes and pollution. Students from FFS training have successfully attempted to introduce and extend banana circles into other countries in Southeast Asia. It has been widely socially accepted and applied in various rural areas in Vietnam, Lao P.D.R., Thailand and Myanmar by farmers’ groups as a cheap and affordable option. In early June 2015, the banana circle solution was awarded as one of the Top 25 most outstanding solutions in the Action for Water Competition 2015 in Vietnam.

Figure 9: Student train-by-practice ‘banana circle’ with people in Thailand (Photo by SPERI, 2014).

Figure 10: Student train-by-practice ‘banana circle’ with people in Myanmar (Photo by SPERI, 2014).

Short-term results from nurseries program

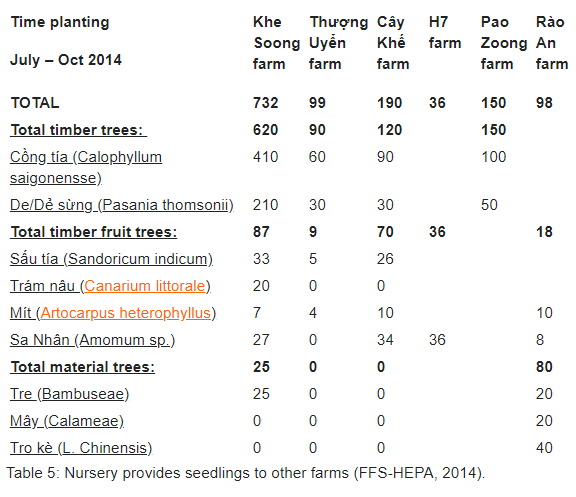

According to the latest data, from July to October 2014, the nursery has successfully nursed 1,500 small tree plants at FFS-HEPA. The table below provides data on seedlings coming from the nursery that were extended to another six running farms of FFS-HEPA. For the 2015 spring season, the nursery is nursing 3,000 seedlings including timber trees, landscape trees and seasonal vegetables.

Discussion

Lessons learnt

FFS training programs have indicated a certain extent and scale of effectiveness. Likewise, there are lessons to be learnt. What makes FFS’s continue is the ongoing dedication and strong will, guided by the leadership structure, toward the necessity to improve ecological systems. FFS’s address poverty and create autonomy for each disadvantaged ethnic minority youth and thus their associated local community. The autonomy allows them to improve local community land use planning and resources management. These are achieved through enhancing knowledge, largely learning-by-doing knowledge, and at the same time facilitating different means of learning:

- Learning from elders: FFS facilitates and strengthens the linkages between youths and their senior farmers by inviting the elders to directly pass their knowledge to students in training sessions. Discussions have led to local solutions to improve local community land use planning and resource management issues.

- Learning by doing: The key point is offering of a practical learning environment where students can practice and relate their knowledge to home villages; they can see certain similarities but also recognize differences. Also, it is important to include actual farms and forest areas in the training fields for real training and actual exercises. Students are able to exercise learning-by-doing, and can experiment by trial-and-error during their learning process.

- Mutual learning: Study tours are held to various sites, pilots and/or practice sites, either successes or failures (e.g. degraded sites or conventional agricultural farms). Interaction between farmers, scientists and traditional knowledge holders, international volunteers and local students are important to increase mutual learning. Knowledge exchanges, especially on management strategies, occur between policy makers, government officials including agricultural extension officers, practitioners, farmers, community leaders, elders and also the students.

- Collaboration with local authorities: Strong collaboration between the FFS and the local authority to prevent illegal logging is an effective approach given that all FFS sites are located at remote border areas and are working to address forest degradation, illegal logging and wildlife hunting. Fostering strong collaboration with local authorities and authorized agencies is crucial to increase the effectiveness of joint actions.

- Nurturing the cultural and spiritual values of the forests and landscapes: Forests and landscapes are not just timber, wood resources or any other economic means. Each forest and hence landscape has a history, a cultural message linked to it since its original formation. The will of people to attempt to conserve resources is often observed in their cognitive realization of the spiritual/cultural meaning attached to a forest and or landscape.

- Integration of traditional knowledge and modern science: The integration of traditional ecological knowledge from ethnic groups is essential for enabling the students to feel proud of their beliefs and local knowledge systems, to not feel disconnected in learning, and to feel empowered to practice.

- Innovation of knowledge: Innovative knowledge is built in the process of running experimental farms and trials. Students are given space to experiment and learn through trial and error. The nursery program has allowed students to test and try new species which can result in the creation of new knowledge. Innovative learning or knowledge enhancement (in order to turn thinking into actions) should be sought from the individual student level to allow students to exercise and create change(s) from the small scale through to a bigger scale.

Challenges

Despite significant positive changes, change has taken years to obtain. There are also challenges involved in FFS operation. The setting up and running of FFS’s is not easy, not only due to the remote locations but also limited access to infrastructure, opportunities and resources. The motivation to provide an alternative learning experience to disadvantaged youths in upland communities – unlike topics offered in the formal schools, e.g. mechanical agriculture, chemical agriculture – is also challenged. While Vietnam is moving towards becoming a modernized and industrialized country, FFS operation encounters another mainstream challenge, especially when young people are tempted to move to cities in search of jobs instead of staying at local places to learn from elders and community members how to revive, conserve, and better manage local resources and ecosystems. Environmental awareness, forest conservation, landscape restoration and/or healthy and safe farming practices continue to be practiced at a relatively low level amongst the Vietnamese public. This hinders FFS operation and certain on-the-ground uptake activities. Financial resources for some graduates to apply knowledge after FFS training programs are also limited.

Conclusion

This paper provides further information on FFS training programs, methods, results and also challenges – specifically regarding the three hands-on programs. What is crucial in our message is that positive changes and better management of SEPLS can be possible if education takes place at the grassroots level, reaches out to many groups including disadvantaged ones, and is delivered with the most practical hands-on components. Promoting further on-the-ground activities as well as increasing farmer-to-farmer learning and action-taking would be the most effective way to allow target groups at the grassroots level to participate and benefit from managing their landscapes. Likewise, it would also create positive changes in their resources management, including the land, forests, biodiversity and other intangible values that are significant to their lives.

References

Baulch B., Chuyen T.T.K., Haughton D. & Haughton J. 2007. Ethnic minority development in Vietnam. The Journal of Development Studies 43: 1151-1176.

Bui, D., 2012. Só d̄ô ̀ vúò́n úóm HEPA. Trung tâm Nghiên cú́u Sinh thái Nhân vă n Vùng cao (CHESH)/HEPA.

HEPA. 2014. Báo cáo công tác phố i hóp bă o vê an ninh trât tú và bă o vê rù́ng. Trung tâm Nghiên cú́u Sinh thái Nhân vă n Vùng cao (CHESH)/HEPA.

Hoang, D. 2014. Gió́i thiêu vế vúò́n úóm cây bă n d̄ia HEPA 7 – 10/2014. Trung tâm Nghiên cú́u Sinh thái Nhân vă n Vùng cao (CHESH)/HEPA.

FAO 2011a. Global food losses and food waste, Extent, causes and prevention. Save Food. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

FAO 2011b. State of the World’s Forests, 2011. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Le, G., 2014. Chiế n lúóc rù́ng hỗ n giao bằ ng cây bă n d̄ia ŏ HEPA. Trung tâm Nghiên cú́u Sinh thái Nhân vă n Vùng cao (CHESH)/HEPA.

Mellor J., Desai G. 1996. Agricultural Change and Rural Poverty. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Muijlwijk, M., 2014. 2014. Food production and consumption in Rao An area – HEPA. Report, 7 October 2014.

Tran, L., 2007. Practical based training programme on agro-ecological farming system. Vietnam: Social Policy Ecology Research Institute.

Tran, L., 2009. Biological Human Ecology and Structural Poverty in Community Development Work among Ethnic Minorities of the Mekong River Valley. Vietnam: Social Policy Ecology Research Institute.