Socio-ecological linkages in Japan’s Urato Islands

22.12.2015

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

22/12/2015

-

REGION :

-

Eastern Asia

-

COUNTRY :

-

Japan (Miyagi Prefecture)

-

SUMMARY :

-

Conservation and sustainable use of natural resources constitute the foundation for human well-being. In the Urato Islands, located off the northeastern coast of Japan, communities have formed strong linkages with surrounding landscapes and seascapes, not only as a source of livelihoods and sustenance, but also in the face of regularly reoccurring natural disasters. Although the magnitude of the 11 March 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami exceeded any such events in recorded history, a combination of strong community bonds, intimate knowledge of terrestrial and marine systems, and cultural richness resulted in a robust and resilient response by local communities, which was further strengthened by external bonds with multiple diverse stakeholders. Field visits were conducted during 2011-2015 to better understand the nexus of social, ecological and production processes that have shaped the communities in the Urato Islands as well as their surrounding landscapes and seascapes. Community dialogue sessions were also organized to facilitate multi-stakeholder dialogue among community members and external actors. Furthermore, a critical assessment is provided of the concepts underlying ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction (eco-DRR) as reflected in the revitalization of communities in the Urato Islands following the events of 11 March 2011.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Urato Islands, eco-DRR, human-nature linkages

-

AUTHOR:

-

Akane Minohara and Robert Blasiak, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo

-

LINK:

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Introduction

[Note: This case study was first published in the Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 1]

Despite technological advances and industrialization processes across the world, humans remain just as dependent on the Earth’s ecosystems for their well-being as ever. In the past, people lived in the proximity of their resource base, giving them a direct and personal interest in sustainable resource management (Olson 2000). Ongoing processes of globalization, however, have often caused production activities to shift into areas characterized by cheap labor costs and limited regulation (Gray 1997), in the process causing a growing spatial disconnect between people and the resources they consume. This distance, in turn, influences people’s perceptions of ecosystems and the services they provide, with some research suggesting that simply being proximate to an ecosystem increases people’s perceptions of its value (Muhamad et al. 2014; Sodhi et al. 2010). But unprecedented rural to urban migration has led to a world in which the majority of people live in cities, and the associated loss of human connections to productive landscapes and seascapes raises considerable concerns about the future of sustainable resource use (WHO 2015).

The landscapes and seascapes of the Urato Islands

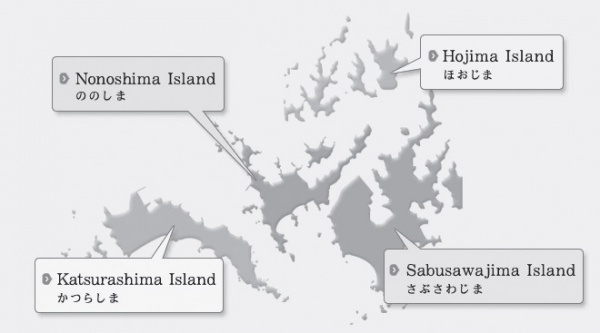

Within this case study, focus is placed on the socioecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS)of the Urato Islands, which are part of the municipality of Shiogama City in Miyagi Prefecture. The Urato Islands consist of four different islands, namely, Katsurashima, Nonoshima, Sabusawajima, and Hojima, with a current total population of about 400 altogether (Figure 1). Mariculture (oyster farming), nori production (seaweed farming) and small-scale coastal fisheries are the dominant maritime production activities, while rain-fed agriculture on the islands themselves is largely a source of supplemental foodstuffs for local consumption (Figure 2). The Urato Islands and the surrounding Matsushima Bay are also firmly embedded in the cultural fabric of Japan, and are known not only as one of the “Three Views of Japan”, but also as the setting for many well-known stories and tales. When Albert Einstein visited Matsushima in 1922, it is said that he remarked how “No great artisan could reproduce its beauty”. Likewise, Franz Doflein, one of the first marine biologists to visit Japan, dedicated a considerable part of his surveys to the Urato Islands and surrounding areas due to the complex mixing of ocean currents off the shores and the cultural richness of the region. On one rainy day in 1906, he sailed through Matsushima Bay noting the many fishing boats, before landing on an island where he provided a 100+ year-old description of Japanese SEPLS (satoyama and satoumi): “I walk westwards among the rice fields. The area is richly cultivated; mulberries cover some areas, and many of the country’s common vegetables are being grown: beans, cucumbers, melons, eggplants. In between there are thickets and patches of forest […]” (Doflein 1906).

Figure 1: The Urato Islands (Source: Shiogama City 2015)

Figure 2: Socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes in the Urato Islands (Photo by Akane Minohara)

Resilience of the Urato Islands to earthquakes and tsunamis

The decision to assess SEPLS in the Urato Islands is based not only on the long history of strong human-nature linkages (Flint et al. 2013), but also due to the fact that these communities are located in a highly disaster prone region. While earthquakes and tsunamis remain largely unpredictable in many ways, the Gutenberg-Richter model identifies the logarithmic relation between earthquake frequency and intensity. Accordingly, not only have major earthquakes shaped the region, but earthquakes of 6.5 magnitude or more can be expected on an almost annual basis (Silver 2012). On 11 March 2011, the largest earthquake and tsunami ever recorded in Japan’s history struck off the northeastern coast of Japan. As of 11 March 2015, official records state that 15,891 people lost their lives and 2,584 people are still missing, with more than 400,000 houses being completely or partially destroyed (National Police Agency 2015). The Urato Islands were partially submerged under a series of huge waves, which washed away houses as well as aquaculture facilities and equipment, causing severe damage to the livelihoods of residents. Although three people went missing from one of the islands, no other casualties were reported. Residential infrastructure was heavily impacted, however, with 166 houses across the Urato Islands being completely or partially destroyed. Subsequently, 48 temporary housing units were built for those who lost their homes, but some residents, mostly elderly, left the islands completely to live with their children’s families now living on the mainland (Shiogama City 2014). In March 2015, the much-anticipated disaster recovery public housing units were completed, and 23 households on two of the islands started their new lives there, while the temporary housing residents on the other two islands are still waiting in their tiny prefabricated houses (Shiogama City 2015).

In this case study, we consider how loss of life under such extreme conditions was minimized in the Urato Islands and the potential role that SEPLS and cultural linkages played in mitigating the damage. Likewise, focus is placed here on the resilience of these SEPLS in the years following the 2011 disasters. Within the context of climate change and the projected increase in frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, understanding and promoting resilience in the face of disasters is of crucial importance (IPCC 2012).

Methods

A number of field visits were conducted in the Urato Islands during 2011-2015 in order to observe the recovery process of the communities and the people’s livelihoods. The research was primarily conducted using formal and informal interviews with local people and relevant stakeholders, and through observations of their daily lives as well as key events. Qualitative ethnographical approaches such as semi-structured interviews using snowball sampling and participant observation were employed to deal with issues that are often highly sensitive and emotional, while making continuous efforts to build trust with local people.

In addition, two community dialogue sessions were organized in August 2012 and April 2013, respectively, by Tohoku University and the United Nations University in collaboration with other members of the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI) including the Ministry of the Environment of Japan, Ink Cartridge Satogaeri Project (Brother, Canon, Hewlett-Packard, Lexmark and Seiko Epson) and CEPA Japan as part of an IPSI collaborative activity [further information about IPSI collaborative activities available online at: https://satoyama-initiative.org/old/en/partnership/activities/], where people from the four islands and various stakeholders gathered together to discuss rebuilding and revitalization of the islands (Figure 3)*. These two community dialogue sessions built on a multi-stakeholder platform and were key turning points for the rebuilding process of the Urato Islands as a whole. Not only did they allow the islanders to express and share their anxieties, concerns and future hopes, most of which had been left largely unspoken, but also provided opportunities to materialize their hopes into more concrete actions through sharing them with external stakeholders as well as to bring together various ideas and thoughts. Key guiding questions for the community dialogue sessions are presented in Tables 1 and 2 (for more details, see IPSI 2012 and 2013).

[* The objectives of the collaborative activity were to: (1) rebuild and restore the disaster-affected SEPLS aligned with natural processes; (2) revitalize and support communities in a sustainable manner, built upon local nature, culture and industries to overcome deep-rooted problems of depopulation, aging populations and a lack of successors; (3) develop a model of post-disaster restoration and revitalization of communities in decline, and share the lessons learnt with the rest of Japan and abroad. For details of the community dialogues, see https://satoyama-initiative.org/old/en/community-dialogue-seminar-in-tsunami-affected-tohoku-region/ (First community dialogue in August 2012) and https://satoyama-initiative.org/old/en/2nd-community-dialogue-seminar-held-in-japans-tsunami-affected-tohoku-region/ (Second community dialogue in April 2013)]

Figure 3: Active interaction among islanders and external stakeholders during the two community dialogue sessions (Photo by IPSI Secretariat)

Table 1: Key questions from the first community dialogue session (August 2012)

| Key questions |

| 1) Things that they are proud of in their communities; 2) Things that they feel anxious about (before and after the tsunami); 3) Ideal future for their communities; 4) What each person can do for their communities. |

Table 2: Key questions from the second community dialogue session (April 2013)

| Key questions |

| What can be done by (a) 1 person, (b) 10 persons, and (c) 100 persons in order to 1) Prevent further population loss; 2) Create mechanisms to attract people from outside the islands; 3) Maintain the environment to continue living on the islands. |

Results

Socio-ecological production linkages

There is a growing recognition that biological diversity underpins ecosystem health and thus the resilience of natural systems (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005). Likewise, diversity of culture, which includes lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs (UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity 2002), is considered to be an integral component of many ecosystems (CBD COP Decision V/6), and has the capacity to increase the resilience of social systems (Pretty et al. 2009). Such considerations have led, among other things, to a range of literature on socio-ecological systems (SES) examining how site-specific natural resource management has evolved into coupled systems where the ecological characteristics of a system are inextricably linked with the cultural characteristics of the people interacting with it (Binder et al. 2013). The concept of socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS) further expands and strengthens this definition by placing emphasis on the potential for such coupled systems to be specifically shaped to ensure long-term productive capacity, the basis for human well-being and sustainable societies throughout history (Blasiak and Nakamura 2013). According to Gu and Subramanian (2014), SEPLS are “dynamic mosaics of habitats and land uses that have been shaped over the years […] in ways that maintain biodiversity and provide humans with goods and services needed for their well-being”. The complex interactions between nature (biological diversity) and culture (cultural diversity) that form SEPLS over time are defined by the rich variety of local knowledge often referred to as Traditional Ecological Knowledge, which dynamically adapts to help “monitor, interpret, and respond to dynamic changes in ecosystems [while increasing resilience or] the capacity to recover after disturbance, absorb stress, internalize it, and transcend it” (Berkes et al. 2000: 1252). Such a “knowledge-practice-belief complex” gradually develops and improves through trial-and-error learning (Berkes et al. 2000), and has played a critical role in the survival of islanders who are especially vulnerable to rapidly changing natural environmental conditions (Hong 2013). In the Urato Islands, a variety of locally-adapted and socially embedded knowledge and practices that help to cope with dynamic changes were observed during this study.

Over many years, people in the Urato Islands have nurtured harmonious relationships with their surrounding SEPLS, and developed an in-depth knowledge of how to maintain them in a sustainable manner. Many examples exist, for instance where the communities spontaneously set dates on which clams were to be collected, as well as upper limits for the maximum amount that can be harvested each year to avoid overexploitation of this common resource. In 2015, one person per household with fishing rights is allowed to harvest up to 10 kg of clams at a time in a designated container at allocated beaches (in rotation) on six occasions in total between mid-April and mid-May, while simultaneously being encouraged to remove Glossaulax didyma, which has caused severe damage to the clam populations of the islands (Interview, April 2015). There is no formalized rule as such, but community members spontaneously organized themselves to set the limit, since they noticed a decline in clams due to an increase in alien species. In another example of optimal use of natural resources in the Urato Islands, although starfish are regarded as an enemy by fishermen, the local practice is to use collected starfish for productive purposes. After first drying them in the sun, the starfish are applied as a natural fertilizer to vegetable crops to boost yields in the productive landscapes near the seashore (Figures 4). Crushed oyster shells, which are categorized as industrial waste by the local government, are also optimally used as a source of soil/plant nutrition in the vegetable fields. These are examples of the cyclic use of resources based on traditional knowledge or wisdom that is unique to the SEPLS in the remote Urato Islands, where cultural practices have developed to make optimal use of available resources. While not all these practices are specifically regarded as adaptive or coping mechanisms by the islanders, many expressed their wish to continue living in harmony with nature, and to pass their experiences and skills on to the new generation (First community dialogue, August 2012).

People in the Urato Islands also exhibit a deep-seated feeling of awe and appreciation for nature, which finds expression in a range of different ways. There is a stone monument to which people used to pray for rain, and each island still holds an autumn festival every year for good harvests. Passing down such traditions and customs seems to have also strengthened the cultural and spiritual linkages of the communities with their surrounding landscapes and seascapes, forming vibrant SEPLS. Meanwhile, some community members express regret that certain traditions are disappearing, a change which they primarily attribute to the aging population of the islands, which is considered to be a serious challenge (First community dialogue, August 2012). People in the Urato Islands, like many other coastal communities in Japan, see the mountains and sea as being connected and understand that protecting the upstream environment results in better harvests in the downstream near-shore ocean areas. Based on this belief, it was once common for fishers’ households to make a pilgrimage to Shinto shrines located on the hilltops of the Three Mountains of Dewa (Dewa Sanzan), which are located far inland within the Tohoku region and are considered as sacred sites for fishers among others. This tradition, however, has not been practiced for many decades.

Figure 4: A unique example of making full use of local resources: starfish, which are considered a pest by fishermen, are utilized as a natural fertilizer for crops (Photo by Akane Minohara)

Response to disaster

Living side by side with nature means that people receive both the blessings provided by the SEPLS surrounding them, but also that they could potentially be more vulnerable to disasters caused by extreme events such as earthquakes, typhoons and tsunamis. Although the residents of the Urato Islands are implicitly exposing themselves to higher risk, they fully understand this duality of nature, and simultaneously embrace both its bounty and its dangers. One of the oyster masters on the Urato Islands, who has devoted his efforts to oyster farming over the last few decades, once remarked that every year he is a first-year student when it comes to cultivating oysters, as each year is different: there are good times and bad times. Other oyster farmers also explained how they modify their methods and techniques every year in an effort to achieve better harvests without causing negative impacts on the sea. This type of adaptive management using trial-and-error learning is commonly practiced throughout the Urato Islands and the surrounding sea. Following the same global trends previously mentioned, many people, especially those who are young, have left the islands and moved to cities to seek lives with greater stability and more convenience. Those who remain on the islands, however, are maintaining the cultural traditions of the past, while continuing to develop and adapt their production and distribution activities to meet the realities of an interconnected and interdependent world.

The fact that there was almost no loss of life in the Urato Islands as a result of the tragic events of 11 March 2011 was considered by many as miraculous, given the magnitude of damage to the islands and the aging populations of the communities. However, it is too simplistic to conclude that the communities were simply lucky. Discussions with local community members underscore that many lives could have been lost if the strong bonds that connect the community members did not exist. In fact, over the course of the community dialogue session in August 2012, it became apparent that islanders have a high level of pride in the strong community bonds that are built on deep humanity. Other points of pride that they mentioned share this same cultural dimension, but were related to the aesthetically beautiful landscapes and seascapes as well as tasty local delicacies, among other things. In contrast to the anonymity of urbanized areas in modern Japan, the communities of the Urato Islands still maintain a culture of helping one another, which has been deeply embedded in their daily lives. While it is difficult to quantify such actions in a precise or statistical manner, it is nevertheless a common occurrence to observe someone giving a helping hand to another without a moment’s hesitation. Likewise, in the Urato Islands, people never lock their front doors, because they know their neighbors are remaining watchful of the whole community even when they are away from home. Another mechanism that results in strong community bonds is the practice of local women to frequently visit each other’s houses to drink tea and bring along small ‘gifts’ – fish caught in the morning, vegetables just harvested, or one of their specialty dishes. Gift exchange was seen as playing a key role in forging social bonds in pre-industrial societies (Lévi-Strauss 1969), but is still highly relevant and deep-rooted in Urato Island communities as a social lubricant. When the 11 March 2011 earthquake hit the Tohoku region, the bonds formed by all of these bits and pieces of communal life were tested. People reacted immediately and took sensible action even in the face of an unprecedented event, running into the houses of elderly residents without even pausing to remove their shoes, before loading them into the back of vans and taking them to an evacuation site at the top of a hill. In the weeks after the initial disaster, these bonds continued to manifest themselves in the way people supported each other in the evacuation center when there was a lack of regular provisions of food, water, gas and electricity. After the disaster, it was common for evacuation centers to distribute foodstuffs only when they had enough and an equal amount for everyone in order to avoid conflicts among the evacuees. However in the Urato Islands, such restrictions were not necessary as it was ‘business-asusual’ for them to share a piece of bread with a couple of people, and instead they set their own rules for providing larger amounts of food to those who engaged in physical reconstruction work, as well as children at a rapid stage of growth (Interview, 2015).

First community dialogue session (August 2012)

In addition to these strong community bonds, the involvement of various external stakeholders from outside the communities has played a critical role in accelerating the rebuilding process in the Urato Islands, while bringing together the residents of the four different islands for collective action. Given the situation the islanders were facing prior to the 11 March 2011 disasters, including depopulation, an aging population and the decline of local industries due to a lack of young successors, a tacit understanding exists among the local people that simply returning to the pre-disaster situation would not solve the deep-rooted challenges and revitalize their communities. As reflected in the diverse range of participants in the two community dialogues sessions, a wide range of stakeholders, including NGOs, universities, the private sector, local and national governments, a UN organization, and other individuals have joined together in support of the islanders not only as they recover from the disaster, but also as they seek to move forward. The first community dialogue session, held in August 2012 primarily focused on collecting the opinions and visions of islanders about the strengths of their communities, as well as negative trends and the ideal future characteristics of the islands. An overview of the key questions raised during this session is included in Table 1.

Second community dialogue session (April 2013)

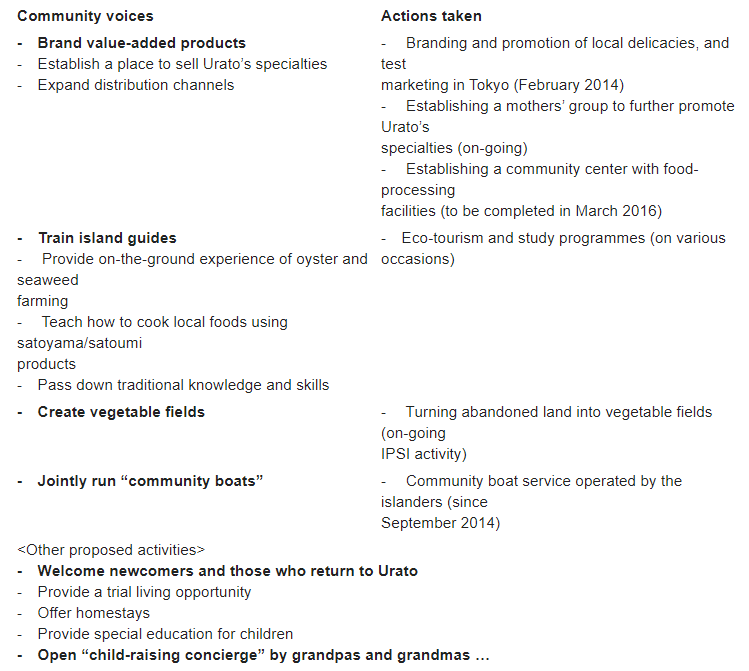

Building on the outcomes of the first community dialogue session, the process was continued. A second community dialogue session was therefore organized in April 2013 for discussion and presentations that took into consideration the importance of multi-stakeholder collaboration and the unique sets of ideas on how to overcome various challenges that the Urato Islands have been facing, namely to: 1) prevent further population loss, 2) create mechanisms to attract people from outside of the islands, and 3) maintain the environment to continue living on the islands. Among the topics that were discussed (see Table 2), some have since materialized or are in the process of doing so, for instance the branding and promotion of local delicacies, especially mothers’ home-made cooking (Figure 5a), conducting eco-tourism or study programmes to introduce visitors to the beauty of nature, the people and their livelihoods (Figure 5b), attracting external funding to build a processing space to produce value-added products, and turning abandoned land into vegetable fields. These and other proposals were voiced by participants and subsequently shared with the group – a selection of these is included in Table 3.

Table 3: A selection of community voices from the two community dialogue sessions and some of the actions taken (as of August 2015)

Figure 5a: Urato Island “mothers” selling home-made oyster curry and oyster chowder at a farmers’ market in Tokyo (February 2014)

Figure 5b: An oyster farmer giving an on-the-boat lecture for an international summer seminar in the Urato Islands (August 2014) (Photo by Akane Minohara)

Discussion and conclusion

The community dialogue sessions are the basis for a substantial component of this research and have been crucially important for the post-disaster recovery and revitalization efforts in the Urato Islands. As a methodology, community dialogue sessions using a similar approach could be broadly applicable within both post-disaster settings as well as communities struggling to address deep-seated challenges. Key factors that enable their broad applicability include their inclusiveness, which enables a range of stakeholders to both participate and feed their thoughts into change processes, and the ultimate usefulness of such dialogue to serve as a catalyst for action, setting long-term change processes in motion in an organic and locally-owned manner.

This research in the Urato Islands has also underscored how strong community bonds, supported by a solid knowledge base about surrounding SEPLS and a wide range of coping strategies such as self-organization of managing the commons and adaptive management through trial-and-error learning, can lay the foundations for an entire community’s resilience. This effect is further strengthened through external linkages with various stakeholders. Even the community members who are considered to be the most vulnerable are supported by these community bonds, which play a key role in disaster risk reduction despite the magnitude of the disaster. Currently, there is growing attention to the possibilities of ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction (eco-DRR) rather than conventional hard engineered solutions (Renaud et al. 2013). Given that the magnitude of disasters can vary due to human-induced factors, it is sensible to incorporate local socio-ecological knowledge based on people’s longstanding mutual relationship with their surrounding SEPLS in a more active manner in order to reduce underlying risk factors. Nevertheless, the massive movement of people from rural to urban areas should not be seen as precluding the possibility of community bonds, but rather underscoring the need for informal social mechanisms such as the “tea time” in the Urato Islands that strengthen connections. With the diversity of local customs that are surely represented in each urban area, there is no lack of potential mechanisms for strengthening these bonds, but perhaps the lack of a shared production landscape or seascape is one reason for weak human-nature relationships in urban areas.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the people of the Urato Islands, who have always welcomed us with warm hospitality and graciously shared their knowledge and time. We are also grateful to Prof. Hisashi Kurokura, the University of Tokyo, for thought-provoking discussion and valuable advice on resilience and community politics in post-disaster period, as well as to our colleagues at the IPSI Secretariat and all who worked together on the IPSI collaborative activity in the Urato Islands and beyond – Tohoku University, Ministry of the Environment, Ink Cartridge Satogaeri Project, CEPA Japan, e-front, Yamagata University, Mr. Masahiro Shida to name but a few – for their invaluable support. This work was made possible, in part, due to support from Japan Science and Technology Agency and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant number 4403) “New Ocean Paradigm on its Biogeochemistry, Ecosystem and Sustainable Use”.

References

Berkes, F., Colding, J. and Folke, C. (2000) Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications 10(5): 1251-1262.

Bindler, C.R., Hinkel, J., Bots, P.W.G. and Pahl-Wostl, C. (2013) Comparison of frameworks for analyzing socialecological systems. Ecology and Society 18(4): 26.

Blasiak, R. and Nakamura, K. (2013) Agricultural heritage across the millennia. United Nations University Our World. Retrieved on 17 March 2015 from: http://ourworld.unu.edu/en/agricultural-heritage-across-the-millennia

Convention on Biological Diversity (2000) CBD COP Decision V/6. Retrieved on 15 April 2015 from: https://www.cbd.int/decision/cop/default.shtml?id=7148

Doflein, F. (1906) Ostasienfahrt [English: Travels in East Asia] B.G. Teubner Verlag Leipzig and Berlin, Germany.

Flint, C.G., Kunze, I., Muhar, A., Yoshida, Y., Penker, M. (2013) Exploring empirical typologies of human-nature relationships and linkages to the ecosystem services concept. Landscape and Urban Planning 120: 208-217.

Gray, J. (1998) False dawn: The delusions of global capitalism. Grant Books. London, UK.

Gu, H. and Subramanian, S.M. (2014) Drivers of change in socio-ecological production landscapes: Implications for better management. Ecology and Society 19(1): 41.

Hong, S. (2013) Biocultural diversity conservation for island and islanders: Necessity, goal and activity. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 2: 102-106.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2012) Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: Special report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. New York, USA.

International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI) (2012) Community dialogue seminar in tsunami-affected Tohoku region. Retrieved on 17 March 2015 from: https://satoyama-initiative.org/old/en/community-dialogue-seminar-intsunami-affected-tohoku-region/

International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (2013) 2nd community dialogue seminars in Japan’s tsunami-affected Tohoku region. Retrieved on 17 March 2015 from: https://satoyama-initiative.org/old/en/2nd-community-dialogueseminar-held-in-japans-tsunami-affected-tohoku-region/

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1969) The Elementary Structures of Kinship. Beacon Press. Boston, USA.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA.

Muhamad, D., Okubo, S., Harashina, K., Parikesit, Gunawan, B., Takeuchi, K. (2014) Living close to forests enhances people’s perception of ecosystem services in a forest–agricultural landscape of West Java, Indonesia, Ecosystem Services 8: 197-206.

National Police Agency (2015) Situation of damage caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011 Retrieved on 17 March 2015 from: https://www.npa.go.jp/archive/keibi/biki/higaijokyo.pdf

Olson, M. (2000) Power and prosperity. Basic Books. New York, USA.

Pretty, J., Adams, B., Berkes, F., de Athayde, S.F., Dudley, N., Hunn, E., Maffi, L., Milton, K., Rapport, D., Robbins, P., Sterling, E., Stolton, S., Tsing, A., Vintinner, E. and Pilgrim, S. (2009) The intersections of biological diversity and cultural diversity: towards integration. Conservation and Society 7(2): 100-112.

Renaud, F.G., Submeier-Rieux, K. and Estrella, M. (2013) ‘The relevance of ecosystems for disaster risk reduction’, in The Role of Ecosystems in Disaster Risk Reduction, eds Renaud, F.G., Submeier-Rieux, K. and Estrella, M., United Nations University Press. Tokyo, Japan. pp. 3-25.

Shiogama City (2014) Post-disaster situations in Shiogama City. Retrieved on 17 March 2015 from: http://www.city.shiogama.miyagi.jp/fukko/higai/higaijokyo.html

Shiogama City (2015) Disaster recovery public housing newsletter No. 3. Retrieved on 21 April 2015 from: http://www.city.shiogama.miyagi.jp/fukko/fukko/machizukuri-new/documents/saigaikouei-news3.pdf

Sodhi, N.S., Lee, T.M., Sekercioglu, C.H.,Webb, E.L., Prawiradilaga, D.M., Lohman, D.J., Pierce, N.E., Diesmos, A.C., Rao, M., Ehrlich, P.R. (2010) Local people value environmental services provided by forested parks. Biodiversity and Conservation 19: 1175–1188.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2002) UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity in the Records of the General Conference 31st Session. Retrieved on 15 April 2015 from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001246/124687e.pdf#page=67

World Health Organization (WHO) (2015) Global Health Observatory (GHO) data: Urban population growth. Retrieved on 17 March 2015 from: http://www.who.int/gho/urban_health/situation_trends/urban_population_growth_text/en/