Historical changes of co-management and biodiversity of community forests: A case study from S village of Dong minority in China, 1950-2010

22.12.2015

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Centre of Forestry, Environmental and Resource Policy Study, Renmin University of China

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

22/12/2015

-

REGION :

-

Eastern Asia

-

COUNTRY :

-

China (Hunan Province)

-

SUMMARY :

-

The CBD emphasized the important roles of “in situ conservation” and traditional knowledge, while more local participation and benefit sharing may be crucial to achieve the Aichi Targets in the next five years. Co-management of community forests as “community based nature reserves” may become the key to meet gaps in networks among protected areas. Based on seven visits comprised of 75 days of on-the-ground field research, including county-level archives collection, participatory observation, questionnaire surveys, key person interviews and group interviews, this paper compares the traditional and current situation in the status, technologies, and institutions of forestry and biodiversity in the community forest management in S village in south China from 1950 to 2010. It was found that intention toward agricultural production, decision-making rights in community forest management, degree of fragmentation of forest property and forest classification systems, may be key institutional approaches, while land regeneration methods and harvest periods may be significant technical approaches for the management of biodiversity, through which the co-management regime will impact on the biodiversity of the village. Methodological approaches of influencing the co-management, by both coercive government interventions and respectful academic advice, were also discussed to further enhance understanding of external interventions on community-based biodiversity conservation.

-

KEYWORD :

-

biodiversity, co-management, community forests, forestry policy, Dong minority, China

-

AUTHOR:

-

Minghui Zhang, Boya Liu, Jinlong Liu (Renmin University of China)

-

LINK:

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Introduction

[Note: This case study was first published in the Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 1]

Although protected areas are one of the most important elements for the successful implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (Adams, 2004; IUCN, 2015), they are understaffed, underfunded and beleaguered in the face of external threats (Le Saout, et al., 2013) and have made some negative impacts on local poverty (Adams et al., 2004). However, many traditional forests scattered in Chinese villages with no staff and few funds have preserved various species as “community based nature reserves” (Liu, Zhang & Zhang, 2012; Luo, Liu, Zhang, 2009; Yuan, Liu, 2009), even in the background of rapid social change, such as growing human populations (Mace, 2014), expanding agricultural land uses (Noble, Dirzo, 1997), increasing urban migration (Klooster, 2013) and the rising market value of plantations (Barlow et al., 2007) during the last 60 years. Although the unique role of indigenous and local communities in biodiversity conservation was recognized (UN, 1992; Berkes, Colding, Folke, 2000; CBD, 2010; Rands et al., 2010), the mechanisms and the effectiveness of community-based biodiversity conservation should be carefully studied on the explanation not only of ownership (Agrawal, Chhatre & Hardin, 2008) but also of governance institutions and behavioral patterns (Rands, et al., 2010). In China, with about three sequential differing trends in state-driven regime changes concerning governing forestlands during the 1950s-1970s, 1980s-1990s, and 2000s, community forests were used and managed by a combination of government and local people at different participatory degrees – referred to as different co-management regimes (Berkes, Geoge & Preston, 1991). This paper attempts to illustrate a case study on different forest co-management regimes in S village, where there are community forests and “community based nature reserves”, looking at the years between 1950 and 2010 with great socioeconomic transformations, in order to find out: Are there any approaches that impact good biodiversity conservation of community forests in co-management regimes?

Section 2 introduces an anthropological methodology for data collection; section 3 analyzes the impacts of approaches to community co-management to understand how the status of biodiversity in the village came about. Section 4 gives a brief summary to show the approaches, and section 5 discusses and concludes what kind of co-management approaches can benefit community forest management as well as biodiversity. Rethinking of the influence of field research on the villagers is also discussed by a comparison with the roles of government in the approaches, to further enhance understanding of external interventions in community-based biodiversity conservation.

Methodology

Site selection and field research

Based on the research project “Traditional Knowledge of Dong Ethnic Group and its Implication to Forest Policy” (71163006) funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the S village was selected as one of the key sites for a grounded study because of its “community based nature reserves” – a relatively large area of Fengshui forest [Fengshui ( 風水) forests are a kind of forest classified by local people in most places of southern China. Villagers usually arrange a piece of forest by the sides of their houses or core villages as protection screens for certain reasons based on fortune] with an ancient stone monument for protection of the natural forest. There is said to be only one complete natural forest with a conservation monument in Hunan province, which is a relatively developed province in China. We, at first, wanted to study these Fengshui forests carefully to see why they could be preserved as a whole in their original states despite interventions in the form of numerous forest-related policies that led to conversions to plantations or degradation in other forests since the year 1949, the foundation of the new China. So from June 2012 to January 2015, we conducted a total of seven visits comprised of 75 days of on-the-ground field research in S village, living, eating and working with the villagers and trying to learn their language [The villagers speak the Dong language and Mandarin Chinese. We can communicate by Mandarin Chinese, but the Dong language is still the native language for them to best express themselves]. In the field, our team emphasized the principle of helping without disturbing – with the values of respect, equality, nature-and-ecology friendliness, and an aim to understand social locations in the landscape arrangement, details of the history, and meanings in the culture of the village. The schedules, activities/methods, and outputs/effects of the field research are showed in the Appendix Table.

[While this approach could be considered PRA (participatory rural appraisal) or RRA (rapid rural appraisal), it did not work like that in reality, because our approach was used to merely collect data for understanding the research question and not for some aggressive (or said positive) development or environmental intent. Indeed, we embraced the values of biodiversity, traditional wisdom and nature, but they weren’t delivered on purpose. However, the polite actions and respectful communications mentioned in Table 1 brought us good and friendly relations with the villagers, and also reminded them of need to be more and more caring of their Fengshui forests which are unique and valuable in their lives. In short, our research approach unintentionally triggered the villagers to pay attention to biodiversity conservation in their village. Because their new actions in biodiversity conservation, as mentioned at the end of the paper, were spontaneously started over the last months, it is too early for them to be assessed. Thus, this case only includes the results of our research, which illustrated the effects of biodiversity conservation by villagers themselves in the early history under the interventions of policies. Regarding why they adopted and implemented conservation activities to date, causes may be both related to historical necessity and culture values. We do not think the causes can be explained clearly before we understand the value and the effects of this conservation by community-path.]

Our work in the field resulted in a good trusting relationship with the villagers and the local governments, allowing us to collect reliable field data to make a valid analysis. During these visits, county-level archives on main forestry policy reforms during 1950-2010 and the Chorography of the County were consulted. Questionnaire surveys were administered to 32 households in the village to collect basic information on household resources, livelihood, production, forest management and traditional knowledge at both household and village levels. There were group interviews of elder men to map the boundaries of various kinds of forests (including Fengshui forests). In-depth interviews were also held with key persons, such as the oldest villagers, to obtain information on the history of policy reforms, technical transitions, species and forest changes. The village head was interviewed to obtain information on the current situation and the officials of the county forestry administration were interviewed to understand government-level forestry management. A lot of informal information about the village, particularly the traditional technology, decision-making customs and species important to daily lives, were gathered through interactions with the villagers while the team stayed in the village during the study.

Description of the study village

S village is a traditional hamlet of the Dong ethnic minority. It is located 26°08’N, 109°30’E; along the boundaries of Guangxi, Hunan and Guizhou provinces of southern China at an average altitude of 1,150 meters above sea level (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Location of S village in China

According to the Chorography of the County, temperature is 5.8 degrees average in January and 25.9 degrees average in July; the area has above 1,300 millimeters annual rain fall, 1,400.3 hours average annual sunlight, and 298 days of frost-free season. It has nearly 800 hectares of forestland and 60 hectares of farmland, supporting not only 800 people, but also hundreds of kinds of plants and birds, sometimes wild boars and wild goats (Survey data, 2012). Besides usual timber forests, consisting of oriental white oak (Cyclobalanopsis glauca; 青岡in Chinese), schima superba (Schima superba; 木荷in Chinese), camphor tree (Cinnamomum glanduliferum; 雲南樟in Chinese), maple (Acer amplum subsp. Bodinieri; 三角楓in Chinese) and so on, forests also contain some endangered trees such as nanmu (Phoebe zhennan; 楠木in Chinese), and Chinese yew (Taxus wallichiana; 紅豆杉in Chinese) [They all can be checked on the IUCN “Asia Red List”, produced by ABCDNet]. Nearly all species mentioned above can be found on Houlong Mountain – a piece of the Fengshui forests in S village. It was said that in the past there were more kinds of wild species, especially 50 years ago, than there are currently.

As a traditional Dong minority village, forests have served multiple meanings since ancient times, and there are some special customs related to forests. For over 300 years, villagers have survived by using self-subsistence paddy farming systems and living in wooden houses. They also believe the Fengshui forests can bring fortune to the community and its people (Liu, Zhang & Zhang, 2012), and thus had an ancient cutting ban for protecting the natural status of the Fengshui forests in effect since the Qing Dynasty. Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata; 杉木 in Chinese) plantations of 20 years can be harvested for the construction of shutters, furniture, and daily necessities. Chinese fir logs of 60 years can be used for coffins. Only in cases where money is urgently required will farmers sell out the Chinese fir plantations. This lifestyle has influenced and molded the meaning of the forests in the villagers’ minds, which has gone on to form traditional knowledge for managing the resources for hundreds of years.

With economic and social development dominated by the government since 1949 (Lin, 2007; Wen, 2013), community forests passed through a deforesting and then reforesting process that saw natural forests cut down while artificial forests were expanded. Now, the natural forests form 35% of total community forests, and most of them are located very far away from the core village. The exception is Houlong Mountain, where the forest is next to the core village and functions like a community-based reserve for biodiversity. Population has grown to over two times since 1950, and migrant working has become the main source of income beside agriculture and artificial forestry (see Table 1).

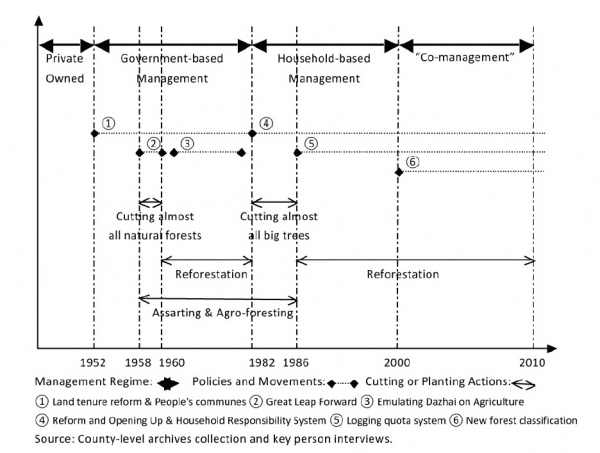

Table 1 illustrates the history in S village of natural forest development and management regime changes. As the regime changed, actions to ruin natural forests rose with great biodiversity loss. The following section will determine what intermediates the relationship between the management regime and forest biodiversity in a common village, and explain the impact mechanism on biodiversity conservation by both government level and traditional community level.

Table 1 Forest, population, and livelihood changes in S Village

Co-management changes and influence on approaches to biodiversity

Forestry policy interventions and co-management changes

In China before the year of 1949, forests in villages belonged to private persons or clans. During the period 1950-1980, some policies on land tenure reform and people’s communes were put in place that improved the collectivization process from the natural resource tenure aspect. All forestlands except state-owned forests regulated by laws were claimed by collectives, and governments as representatives of the collectives had absolute authority to decide on the felling and planting of trees. Especially in 1958-1960 when the “Great Leap Forward” movement [The Great Leap Forward was the attempt of China from 1958 to 1960 to modernize by labor-intensive methods and industrialization] was launched, many natural forests were cut down by the commands of governments in order to make steel as the nation pursued a dream of catching up with the US and the UK. However, during the same era, the so-called “3-year natural disaster period” occurred when food was inadequate in rural areas and nearly all villagers went to forests to look for food, many planting grains on forestlands. In 1964, the “Emulating Dazhai on Agriculture” Campaign was also launched and continued until the year of 1978, concerning farming on mountains. This farming on mountains ruined many forests including natural forests.

In 1979, with the start of the “Reform and Opening Up” policy (MacMahon, Zou, 2011), the regime of forest management was preparing to become market oriented. The “Household Responsibility System” (Mullan, et al., 2011) was launched in the winter of 1981 to allocate the right of forest management to households. Households could make decisions in forestry production by themselves. Until 1986 there were no other restrictions by governments on cutting, so a new excessive deforestation was driven by villagers along with escalation of market price. A “logging quota system” was set from 1986 to impose restrictions on households, requiring them to have certificates to cut trees and finish relevant afforestation requirements after felling trees. But natural forests were still broadly destroyed and reforested with timber species. After grave floods in 1998, the central government began to recognize the ecological function of forests, especially natural forests. Since the year 2000, the county of the S village began to implement a new classification policy of forest management, whereby forests were divided into two kinds: commercial forests and public welfare forests – the latter were determined to include forests beside the national roads, around sources of water, and those in the regions vulnerable to water and soil loss. The area of public welfare forests that cannot be felled covers nearly all the remaining natural forests that were close to villages and roads, and have been subsidized by governments since 2001, with the level of the subsidies improving since 2010 (See Figure 2). There are two kinds of power, from governments and communities themselves, to protect natural forests now.

These above policies impacted community forest management through administration from local governments. To natural forests, the regime for managing village forests evolved from self-management to government-based management, household-based management and then to a kind of co-management. The participatory degree of villagers in making decisions concerning natural forest management ranged from concentrated at first, and then to partially empowered. The following sections of the case study will make clear how the power of government impacted, through re-interpretation by the traditional knowledge, the status of natural forests and biodiversity of the S village.

Figure 2 History of Management Regime Changes and Natural Forest Development in S Village

Approaches based on institutional influence

Community forest co-management may firstly bring institutional change to forestry. There are two types of institutional changes observed in the community forest: property and classification management.

The property of community forests

Before the year 1949 and the establishment of the new China, the community forest was managed by the biggest landowner, who was known as the most powerful and trustworthy elder man in his clan and the village (Luo, 2001). He was responsible for organizing production, adjusting disputes, doing business on behalf of the village, and so on. The social structure of the traditional Dong village was based on blood relations. Including S village, traditional Dong villages regarded rivers, farmlands and forests as the public property of clans, and every villager had to do as the village regulations and customs required.

After 1949, the management agent became the leader of the village and the production team. Institutionally, forests turned into the resources of people’s communes. The government regarded forests as the raw material of industrialization for state construction. In this era, especially the period of the “Great Leap Forward” movement, the intent to industrialize driven by the state caused broad and grave deforestation, to natural forests in particular. Elder villagers reported that tremendous amounts of big trees were cut in valleys, even those which could not be embraced by five people, because of imposed commands from the commune that might result in punishment if disobeyed. Many villagers felt regret that numerous big felled trees rotted because they could not be delivered out of the valleys due to lack of forest roads.

From 1981 the household-contract responsibility system in agriculture was operated, and farmlands were assigned to each household, with the result of basically solving the problem of food and clothing. Then implementation of the “Three-fixes” policy in the forestry area was implemented, and the management rights of the community forest returned to the households. According to household surveys, 15 of 32 respondents cut and planted trees in the 1982-1986 period, comprising an area one fifth of the total reforesting area of the samples. The official of the county forestry administration interpreted, “The forestlands belonged to households, and forestland area per household was relatively small (about 3.4 hectares), let alone to the area per unit (about 0.7 hectares) [This is smaller than the smallest area of a forest compartment (1 hectare) in the concept of forestry science]. Because of tiny areas per unit of the forestlands, households would choose to cut more broad-leaved trees to plant more fir or pine trees to make more money, so that most of them didn’t care, but cut whatever trees, big or not, on their forestlands.” Recently, the criterion for reforesting formulated by the provincial forestry administration was promoted with reforesting subsidies, but if households did not want to gain the subsidies, they might neglect the criterion. Since 1986, the government enforced the “logging quota system”. If households wanted to harvest trees, they had to apply for the cutting quota to the local forestry administration. The official would design a cutting plan according to the approved quota regulating the boundaries and the paths of the new forestry road. For the sake of fragmentation management as a result of the “Three-fixes” policy, various forestry roads also made mountains segmented into pieces, potentially significantly affecting the movement of animals (Chen, 1999).

Figure 3 The Fengshui map, the big pine tree, the Houlong Mountain and the stone monument for cutting ban, in S village (Source: the map was drawn by Minghui Zhang according to the group interview of elder men; the photos were taken by Ms. Jeongja, Lee.)

After 2000, 21% of S village’s area was classified as public welfare forest, to some extent protecting nearby natural forests and the wholeness of partial forests, and benefiting biodiversity. However, the subsidies seemed not enough to meet the needs of the households of the public welfare forests, even when the amount given was growing. It is said that a staff person of the county administration who was not a villager of S was arrested by the forest police, for he secretly set fire to his public welfare forest on purpose, thinking he could sell the burned trunks of trees for more money legally. Unfortunately, he could only be capricious in the prison after this.

Classification management

Before 1949, use and conservation decisions regarding the resources of the whole village were made by the landlords. The landscape of S Village was designed as a wood raft berthing beside the river, backing Houlong Mountain and anchored by an old pine tree (See Figure 3), so predecessors set conservation rules for preserving the Houlong Mountain and the old pine tree. According to the perspectives of these rules, forests in S village were divided into two parts of Fengshui forests and timber forests. Though the classification system was different from the policies of the state, villagers still obeyed the customs of protecting Fengshui forests during every era.

Predecessors made an oath with blood on the cutting ban of Houlong Mountain and established a stone monument with official characters [Dong minority has no writing characters. To our understanding, they used the official characters – Han characters ( 漢字) – to show formality to villagers and respect to strangers] during the Qing dynasty (1636-1912). Nobody could be admitted to cut Fengshui trees. Villagers believed that the person who cut Fengshui trees would get sick and even die; not only that, the person would have to kill his pig to share with every villager, warning other people to obey the cutting ban [The first time, one of landlords let his wife cut a small branch on Houlong mountain, seen by others as intentional, and then killed his pig to give to every villager as a punishment. A pig was expensive to a household and ancient villagers could eat meat only during festivals. So the cutting ban and the punishment took effect as a custom until today]. Even during the “Great Leap Forward” era when the government commands were king, villagers made every endeavor to protect Fengshui trees. An elder villager told us that they beat a wok into the trunk of the old pine tree so that it could not be cut down by other workers from the commune. Regarding timber forestlands, traditional knowledge also existed to protect big trees and biodiversity (See Section 3.3).

From 1950 to 1980, external leaders and political campaigns were active, but the villagers tried their best to protect Houlong Mountain. After 2000, the area of ecological public welfare forest was divided by the government without negotiation with the villagers, and the villagers were informed of the results. Houlong Mountain was the ecological public welfare forest. All villagers so agreed, thus no one destroyed Houlong Mountain or argued to possess its subsidies: Houlong Mountain belongs to the whole village, which has been the consensus in the village generation by generation. Now, officials of the county forestry administration have said that there were thousands of kinds of trees, and more than six hundred-year-old ancient huge trees, that are the habitat of many kinds of birds, such as little egrets (Egretta garzetta; 小白鷺in Chinese). The primary school of the S village stood in front of Houlong Mountain for hundreds of years. After school, whatever eras, children were keen to go to the mountain to pick wild flowers, look for honeycombs or seek wild fruits. “Houlong Mountain is a unique sign of the S village,” the villagers said to us.

Approaches based on technical influence

S village, located alongside the Yangtze River Basin, provided timber for the royal house via rivers perhaps since the late Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Over hundreds of years, they formed their unique technology in managing forests. This technology has been partly changed due to the influence of modern knowledge brought by governments during eras. Co-management may also bring technical combinations.

The Dong minority’s traditional artificial forests were a kind of farm-oriented forest – from the Qing dynasty, predecessors of the Dong created a set of tree-cultivation technologies, including controlled burning for artificial land regeneration, intercropping with agricultural and forestry plants, forest tending by farming, thin planting and clear cutting (Shen, 2006). Fir trees were the traditional main species of artificial forestry which needed over 20 years to be harvested as timber for building houses, or over 60 years to be used as coffin boards. It was observed that controlled burning and firewood chopping, hole depth for planting trees, and harvest time might have changed after modern interventions.

Controlled burning and firewood chopping

Though controlled burning as a method for artificial regeneration is controversial, the Dong minority has used it for hundreds of years. Employed in a traditional way, fire could not burn down big broad-leaved trees that that ancient villagers preserved. It was even ruled that nobody could cut these wild trees, because, for example, the Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra; 楊梅in Chinese) might provide fruit for food, the Tung oil tree (Vernicia fordii; 油桐in Chinese) for house painting, and the cubeb litsea tree (Litsea cubeba; 山雞椒in Chinese) for cool relaxing. Including chopping for firewood, elder villagers would not cut big trees. Most elder men believed there were gods in the wild big trees.

But nowadays, mainly due to the smaller fragments of forestland, disenchantment and modern science, as well as more tools that facilitate lower cutting costs, households have usually chosen to cut all the big trees when they prepare soil for more space to plant fir or pine trees (Pinus massoniana; 馬尾松in Chinese) or bamboo (phyllostachys pubescens; 楠竹in Chinese), that can be expected to sell for a good price. Hence, in the timber area as a traditional classification of the community forest, the more “valuable” species of fir, pine and bamboo remained.

Depth of the hole

Traditionally, villagers thought that there was no significant difference in the depth of holes dug to plant trees in S village, so they usually dug shallow holes for convenience. During the 1980s, an afforestation project in S village supported by the World Bank required villagers to dig a 1 meter* hole for planting a fir tree. Officials of the project even made a mould to measure the holes. The official of the county forestry administration told us that the technology of the World Bank might be better, because the deeper hole was beneficial to loosen the soil, making more humus buried and helping the growth of trees. Furthermore, the trees planted according to the requirements from the World Bank needed only 12 years to reach the harvest period, while ones planted by the traditional method needed 15-16 years or longer. Nowadays, some villagers support the technology of the World Bank; other villagers still consider there to be no distinct gap between deeper or shallower holes, and also consider the costs of time and labor.

Harvest period

The traditional harvest time was usually 20 years for timber and 60 years for coffins. In present day, harvest time is decided by the logging quota system, which gives consideration more to the volume of forest stock, making the harvest time potentially shorter than the traditional one. Regretfully, we have limited knowledge and tools to measure the species and amounts of soil microorganisms to confirm whether or not the shorter harvest cycle influences the quality of soil. A piece of data given by an official of the forestry administration in Jinpin county, where there is also a Dong minority area, showed that this generation of fir artificial forests has revealed degeneration, but it was unclear as to whether the cause was pure forests or the shorter harvest period.

Conclusion and lessons learned

Conclusion: a framework of co-management impacting on biodiversity

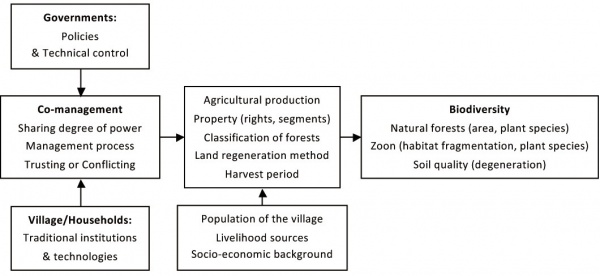

Based on the above analysis comparing the traditional and present day in status, technologies, and institutions of forestry and biodiversity in S village, a summary can now be given to show what approaches may influence the role of co-management in biodiversity conservation (Figure 4). Intention toward agricultural production, decisionmaking rights in community forest management, degree of fragmentation of forest property and forest classification systems, may be key institutional approaches, while land regeneration methods and harvest periods may be significant technical approaches through which the co-management regime will impact on biodiversity. These approaches should be given attention, for management regimes may significantly impact the conservation of biodiversity.

Lessons learned: stakeholders and biodiversity conservation

Since 1949, the orientation of forestry policies has been changing over several eras, revealing a “centralization – decentralization – co-governance” process in the forestry administration of the state. This process brought different management regime changes of “self-management – government-based management – household-based management – co-management”, which resulted in various conditions of the community forest and biodiversity based on the approaches mentioned above. According to the classical definition by Prof. Berkes and his colleagues, “co-management” refers to an approach to governance of natural resources based on the sharing of power and responsibility between the government and local resource users (Berkes, George & Preston, 1991); it should be seen as a process involving extensive deliberation, negotiation and joint learning within problem-solving networks (Carlsson, Berkes, 2005). Based on this concept, there are four aspects that require discussion related to co-management practices and biodiversity in S village in China.

Figure 4 Framework concluded from the case study

Coercive external interventions may damage local biodiversity.

Imposed commands of government may bring about neglect of local traditional forestry knowledge, whereby local biodiversity needs may not be met by external knowledge. The deforestation of 1958-1960 took place in the process of imposed commands by governments, as well as the “Emulating Dazhai on Agriculture” Campaign during 1964-1979, which might have led to a large scale opening up of forestlands (most formed by natural forests) for more farmlands. In these political movements, the traditional decision-making system had no power against the compulsory tasks and commands.

Weak internal capacity may also result in biodiversity loss after decentralization.

With the lack of traditional management power, in addition to the shocks of market opening, forest decentralization may fail. The deforestation of 1982-1986 was the result of decentralization with the market opening; the result was the opposite of the general theory of decentralization. The new generation of villagers might be have been familiar with the traditions after facing a lack of traditional forest knowledge for 30 years, and they seemed not to have the emotional attachment to the natural forests, rather pursued the market value. As a result, many broad-leaved trees and the rich diversity of trees were lost due to ruthlessness and ignorance.

Figure 5 Spontaneous landscape protective actions in S village recently (Source: The pictures were taken by the villagers in S village recently. The upper-left is discovery of another ancient monument; the upper-right is a new traditional building for an ecological restaurant; the lower-left is corn harvest of ecological agriculture for the next-year’s duck feed; the lower-right is ducks raised by a local ecological method.)

Spontaneous internal capacity building for landscape protection may benefit local biodiversity conservation.

Last year, S villagers were awakened and formed a new self-confidence regarding their village, especially the Fengshui forests – the “community based nature reserves”. They now want to protect their Satoyama landscape in order to recover the entire original appearance of the village to make better lives for themselves (see Figure 5). They have begun to repair their ancient objects (e.g. repairing an ancient pavilion of the Qing dynasty, planning to replant various fruit trees beside the core village). They also have gone out to visit other villages to find out about their special attributes and areas of confidence. Likewise, they have set up positive communication with local town and county governments to consult and acquire administrative resources and support, while the governments with pleasure have provided help according to the requirements of the village. Recently, seven volunteer villagers began cooperating to operate ecological agriculture, the idea to manage their landscape in an integrated manner deriving from amongst themselves. They rent a length of the S river and some waste farmlands as well as forestlands along the river, reusing lands for chemical-free farming and raising of free-range ducks, whose products both satisfy themselves and can be sold in the local market. They were also planning to create a brand for the village to

absorb outsiders into ecological tourism and insiders into landscape conservation in S village.

Respectful external advice may enhance local concern for biodiversity.

The government and this research team are the same as outsiders, impacting the landscape management of S village. But our approach is different from the coercive interventions in the 1960s and 1970s. We visited as observers and consultants to follow and research the landscape management in the village. Respectful fieldwork can help with collecting data to figure out the reality for researcher, while assisting the local people to make findings themselves. Moreover, as Fischer and his colleagues considered (Fischer, et al., 2014), two sides of “co-management” may not work together toward the same aim. We should pay attention to those tacit, informal institutions on the traditional and community side; Likewise, co-management may be constructive on only one side – in some cases, the community side may interpret the policies and then take action toward natural resources (e.g. the forest classification system in this case); in other cases, the government side may force or form the decision-making conditions (e.g. commands in the year of 1958-1960, and fragmentation of forest property rights). So the divergence may destroy the trust between the two sides, leading to degeneration in natural resources. Hence, as academic researchers attaining trust in the field, we are supported by an independent research foundation and have relative objective and broad insights. As such, we could dedicate ourselves to balancing the divergence and enhancing the local area to gain new positive ideas for management innovations.

Article 8(j) of CBD emphasized the important roles of “in situ conservation” and traditional knowledge, while more local participation and benefit sharing may be the crucial to achieve the Aichi Targets in the next five years (Tittensor, et al., 2014). Co-management of community forests as “community based nature reserves” may become the key to meet gaps in networks among protected areas in aspects of both geographic location and financial matters. According to this paper, regarding future implications for co-management of the community forest and biodiversity, the capacity building of communities on collecting as well as using traditional knowledge to realize community confidence may be the first step.

Regarding aspects for future study, in this paper, areas and plant species of natural forests, the fragmentation degree of forestland and the degree of forest degeneration were used to demonstrate the concept of biodiversity in a community forest ecosystem, for these three variables to some extent reveal the species diversity and richness of plants, zoon and microorganisms in the ecosystem. In the future, if these variables can also be measured by better techniques such as GIS and soil monitoring, with more refined concept measures of co-management and approaches, further research may test this framework by more quantitative and persuasive methods.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a part of a research report from the Project “Traditional Knowledge of Dong Ethnic Group and its Implication to Forest Policy” (71163006) funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. We also gratefully acknowledge comments from Dr. Yasuyuki MORIMOTO, Dr. William OLUPOT and all the participants in the seminar organized by IPSI Secretariat and IGES, and thank Ms. Susan Yoshimura and editors for their excellent language proofing and editing work.

References

Adams W.M. 2004, Against extinction: the story of conservation, London, Earthscan, pp. 4.

Adams, W.M., Aveling, R., Brockington, D., Dickson, B., Elliott, J., Hutton, J. & Wolmer, W. 2004, ‘Biodiversity conservation and the eradication of poverty’, Science, vol. 306, no. 5699, pp. 1146–1149.

Agrawal, A., Chhatre, A., Hardin, R. 2008, ‘Changing governance of the world’s forests’, Science, vol. 320, no. 5882, pp. 1460–1462.

Agrawal, A., Gibson, C.C. 1999, ‘Enchantment and disenchantment: the role of community in natural resource conservation’, World Development, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 629-649.

Barlow, J., Gardner, T.a, Araujo, I.S., Avila-Pires, T.C., Bonaldo, aB., Costa, J. E., … Peres, C.a. 2007, ‘Quantifying the biodiversity value of tropical primary, secondary, and plantation forests’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 104, no. 47, pp. 18555–18560.

Berkes, F., Colding, J, Folke, C. 2000, ‘Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management’, Ecological Applications, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 1251-1262.

Berkes, F., George, P, Preston, R. 1999, ‘Co-management: the evolution of the theory and practice of joint administration of living resources’, in The Second Annual Meeting of Iascp – Program for Technology Assessment, Mcmaster University, Subarctic Ontario, pp. 3-35.

Carlsson, L., Berkes, F. 2005, ‘Co-management: concepts and methodological implications’, Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 75, pp. 65-76.

CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity) 2010, Aichi Biodiversity Targets, https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets.

Chen Liding, Liu Xuehua, and Fu Bojie, 1999. ‘The research of pandas habitat fragmentation of Wolong nature reserve’, Acta Ecological Sinica, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 291-297.

Fischer, A., Wakjira, DT., Weldesemaet, YT., Ashenafi, ZT. 2014, ‘On the interplay of actors in the co-management of natural resources – a dynamic perspective’, World Development, vol. 64, pp. 158-168.

IUCN (Feary, S., Kothari, A., Lockwood, M., Pulsford, I., Worboys, G.L.) 2015, Protected area governance and management, Canberra: Australian National University Press, pp. 3.

Klooster, D.J. 2013, ‘Toward adaptive community forest management: integrating local forest knowledge with scientific forestry’, Economic Geography, vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 43–70.

Le Saout, S., Hoffmann, M., Shi, Y., Hughes, A., Bernard, C., Brooks, T. M. & Rodrigues, A. S. L. 2013, ‘Protected areas and effective biodiversity conservation’, Science, vol. 342, no.6160, pp. 803–805.

Lin, J.Y. 2007, ‘Needham puzzle, Weber question and China’s Miracle: long term performance since the Song Dynasty’, Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 5-22.

Liu, J., Zhang, R., Zhang, Q. 2012, ‘Traditional forest knowledge of the Yi people confronting policy reform and social changes in Yunnan province of China’, Forest Policy and Economics, vol. 22, pp. 9-17.

Luo, Kanglong. 2001, ‘An analysis of the social organization of the Dong people’s traditional artificial timber industry’, Guizhou Ethnic Studies, vol. 21, no. 86, pp.100-106.

Luo, Y., Liu, J., Zhang, D. 2009, ‘Role of traditional beliefs of Baima Tibetans in biodiversity conservation in China’, Forest Ecology and Management, vol. 257, pp. 1995-2001.

Mace, B.G.M. 2014, ‘Whose conservation? Changes in the perception and goals of nature conservation require a solid scientific basis’, Science, vol. 345, no. 6204, pp. 1558–1560.

McMahon, P. C., & Zou, Y. 2011, ‘Thirty Years of Reform and Opening Up: Teaching International Relations in China’, Political Science and Politics, vol. 44, no. 01, pp. 115–121.

Mullan, K., Grosjean, P., & Kontoleon, A. 2011, ‘Land tenure arrangements and rural-urban migration in China’, World Development, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 123–133.

Noble, I.R., Dirzo, R. 1997, ‘Forests as human-dominated ecosystems’, Science, vol. 277, no. 5325, pp.522–525.

Rands, M.R.W., Adams, W.M., Bennun, L., Butchart, S.H.M., Clements, A., Coomes, D., Vira, B. 2010, ‘Biodiversity conservation: challenges beyond 2010’, Science, vol. 329, no.5997, pp. 1298–1303.

Sang,W.G., Ma K.P., Axmacher J.C. 2011, ‘Securing a future for China’s wild plant resources’, BioScience, vol. 61, pp.720–725.

Shen Wenjia, 2006. ‘A study on forestry economy and social changes in Qingshui River Basin (1644-1911)’, PhD. thesis, Beijing Forestry University, China.

Tittensor, D.P., Walpole, M., Hill, S.L.L., Boyce, D.G., Britten, G.L., Burgess, N.D., … Cheung, W.W.L. 2014, ‘A midtermanalysis of progress toward international biodiversity targets’. Science, vol. 346, no. 6206, pp. 241–244.

UN (United Nations) 1992, Convention on Biological Diversity, https://www.cbd.int/convention/text/default.shtml.

Wen, T. 2013, Eight crises: lessons from China, 1949-2009, Beijing: China Eastern Press, pp. 3-12.

Yuan, J., Liu, J. 2009, ‘Fengshui forest management by the Buyi ethnic minority in China’, Forest Ecology and Management, vol. 257, pp. 2002-2009.