The Planning and Development of the Chengdu Ecological Zone (CDEZ): A Case study of peri-urban planning for sustainable land management and urban-rural integration

23.12.2024

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

University of Oregon

OTHER CONTRIBUTING ORGANIZATIONS

None

DATE OF SUBMISSION

November 22, 2024

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

China

KEYWORDS

Ecological Zone in Chengdu, Urba-rural linkage, Socioecological Landscapes, Peri-urban planning

AUTHORS

Yizhao Yang, University of Oregon

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Overview of Case Study

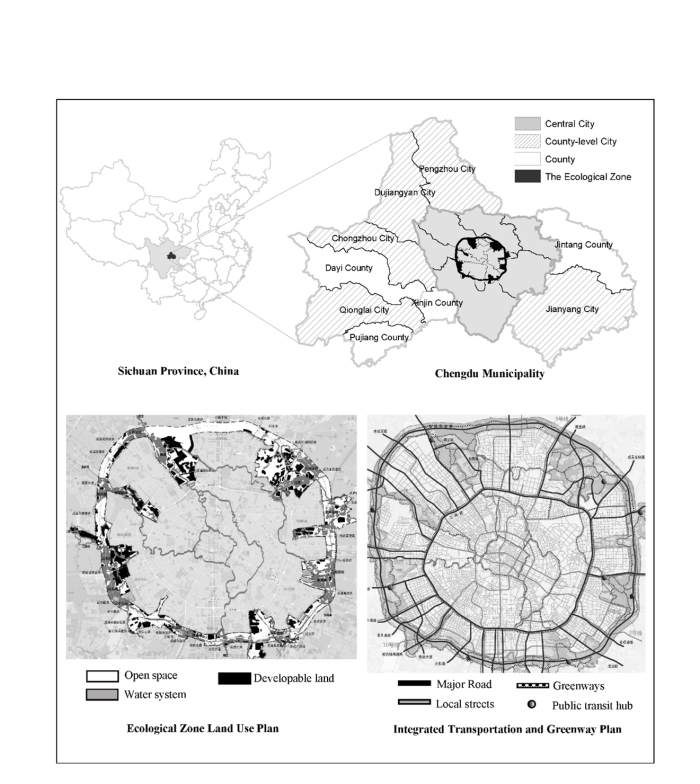

The Chengdu Ecological Zone (CDEZ) refers to a territory comprising a belt of 1,000-meter width centered along the freeway ring road (fourth ring road of the Chengdu Central City) and seven wedge-shaped areas extending between the freeway ring road and the third ring road. This territory of about 198 sq. kms is planned to have 133 sq. kms of public open space organized around an expansive water network and approximately 54 sq. kms of development areas of suitable land uses. Figure 1 shows the CDEZ’s location inside the Chengdu Central City and the Chengdu Municipality, as well as plans for its land use and greenway system.

This case study presents City of Chengdu’s ecological zone (CDEZ) as an example of a landscape approach to building a rural-urban linkage and combatting urban sprawl. As a vital structural and functional territory, the CDEZ not only serves as a spatial tool for urban containment, but also becomes a place that supports synergistic interactions between land uses, populations, and culture and nature. Following a description of the history of CDEZ’s planning and development, this paper summarizes the CDEZ’s characteristics and evaluate its contribution to the city’s development based on the ten guiding principles of urban-rural linkages developed by the UN Habitat (UN Habitat 2019). This case study also sheds light on the fact that CDEZ can’t become a reality without an integrated regional approach to governance, planning, and development which came from some of the fundamental planning reforms in the region as well as in China.

CDEZ Background and Characteristics

Before presenting this case study, it is necessary to distinguish between the city and the municipality of Chengdu. The commonly known Chengdu City, an urbanized area, has evolved from the ancient in-situ Chengdu over the past 2,500 years, accumulating remarkable cultural heritage and earning the title of National Historical Cultural City (Qin, 2015). In contrast, the municipality of Chengdu is a regional or prefecture-level government, formally established in 1994. The municipality was created as part of the central government’s gradual overhaul of the national urban system, which involved elevating many central cities to assume significant management authority over smaller cities and rural areas in their region. In this paper, the term “Chengdu” refers to the entire municipality, while “central city” refers specifically to Chengdu City. By the end of 2019, the central city, consisting of 11 urbanized districts and two economic functional zones, had an urban population of nearly 11 million, while the municipality as a whole had a population of 17 million, covering the central city, five smaller county-level cities, five rural counties, 205 townships, and 2,735 villages.

It should be noted that, over the years, the municipality, the central city, and other smaller cities in the region have gone through constant adjustment to the boundaries of their outer expanse and inner divisions, as more urbanized areas became absorbed into the cities and greater territories annexed into the municipality. Urban planning and land use planning have historically been independently and separately carried out by the cities and counties; a tradition persisted well into the early 2000s. The poorly-coordinated planning framework was further fragmented by the fact that rural and urban lands in China belong to two separate land ownership systems and they are controlled and managed by separate government agencies even when these lands are located in the same city (Yang et al., 2019). All of these conditions were significant barriers to the planning and development of the Ecological Zone and later institutional reforms in the region have played significant role in overcome those barriers.

As the capital of Sichuan Province modern Chengdu’s development has been closely connected to China’s urbanization strategies, especially its westward development agenda. During a relatively stagnant urban development period in the 1960s and the 1970s, the central city had seen its first ring-road built and its a built-up area reaching 58 sq. km by 1978. The following three decades witnessed Chengdu’s extremely rapid growth, thanks to the country’s Reform and Open-up policies and the fact that, in 1999, the State Council designated Chengdu as the country’s western center of logistic, commerce, finance, science, and technology, as well as a hub of transportation and communication. During this period, the central city has added another three ring-roads connected with 16 radiating corridors and its built-up area increased by stunning 6 folds to 355 sq. km by the end of 2010 (Qin, 2015).

Accompanied with such explosive expansion were negative impacts on both sides. On the one hand, increase in urban population confounded with physical urban expansion had outpaced the provision of public facilities and infrastructure, causing over-crowdedness at the urban center, rising commuting distance, and worsening urban traffic and air quality; On the other hand, the peri-urban areas experienced significant loss of arable land, development of low-quality industrial sites and shantytowns, and deteriorating environmental conditions. These challenges also led to growing urban-rural inequalities in various social and economic aspects, similar to the rapid urbanization faced by many other Asian cities (LeGates & Delik, 2014). Recognizing the damages of excessive urban expansion, the central city took a bold step to limit its physical growth by planning and delineating the Chengdu Ecological Zone in 2003 (CDIPD, 2003), which would eventually become an effective component of Chengdu’s overall urban-rural integrated development strategies.

Objectives and Rationale

The CDEZ is conveniently located at the periphery of the central city and takes a belt-wedge mixed shape, comprising a belt of 1000-meter width centred along the freeway ring road (4th ring road of the city) and seven wedge-shaped areas extending between the freeway ring-road the third ring-road. Unlike the traditional urban growth management approach that primarily emphasizes separating the urban from the rural and stopping urban development (Yang et al., 2019), the goals behind the CDEZ include those to reduce the disparities in urban-rural in income, provide economic opportunities and public services, improve rural built environment, and increase land use efficiency. The principles underlying the CDEZ’s planning and development are based on prioritizing ecological conservation, respecting local history and culture, enhancing resource utilization via multifunctional development, and maximizing public access and services (CDIPD, 2012). In other words, CDEZ is intended to be an urban-rural linkage where nature and the human settlements co-develop and co-evolve. The making of this ecological zone is of an incremental process that has witnessed the maturation of CDEZ’s planning and benefitted from reforms in a broader administrative system.

Description of CDEZ Development Activities

The process began in 2003 when the central city included the CDEZ in its comprehensive plan as a tool to systematically manage and control the undeveloped lands in the peri-urban region, with a goal to shape the city into a more compact urban form and enhance ecological functions of those lands. The city conducted extensive surveys and research to take a stock of the current conditions and mapped out a land use plan for this territory. The CDEZ was estimated to contain an area of 198 sq. km at that time, giving it a nick name “the 198 Green” that was frequently used in official documents and popularly known to local residents (CDIPD, 2003). Inside the CDEZ, approximately 74 sq. km was already developed at that time in spatial patterns and forms considered inefficient and poorly serviced; about 16% of the development had been carried out illegally (Zeng, 2017). The central city had two main objectives then for the CDEZ’s development– 1. optimizing the land use intensities and patterns while stopping the increase of developed area, and 2. improving ecological value of open space and farmland. But the central city wasn’t successful at advancing either objective due to the fact that its planning authority was restricted to only a fraction of the lands inside of the CDEZ where land tenure is mixed, land use right and boundaries of many parcels were ambiguously defined, and land use planning authorities were divided among 11 governments.

Significant changes happened in 2007 when Chengdu became one of the two first pilot municipalities in China to adopt an urban-rural integrated planning approach, which, together with a series of other important institutional reforms, allowed the central city to formally include the CDEZ in the making of its comprehensive plan. CDEZ also became one of 13 functional zones designated for the entire region to receive integrated management and strategic investment. A vision of the CDEZ emerged as a territory dominated by green space (parks and farmland) and containing strategically selected development land uses at a moderate and suitable scale, where ecological cultivation and economic development take place simultaneously. This vision took a concrete shape in 2012 when a Comprehensive Plan for CDEZ was officially adopted. The plan provides a blueprint for CDEZ’s future, where a large and expansive water network comprising 6 constructed lakes and 8 wetlands serves as the backbone of CDEZ’s 133 sq. km of open public space (Yin, 2016). Development area is limited to a total of 54 sq. km, where agritourism, recreational services, and compact rural settlements with adequate public facilities represent permissible land uses. Table 1 summarizes the details and features of CDEZ plan and development outcome in spatial, socioeconomic, ecological, and governance dimensions.

Table 1. Planning and Development Characteristics of Chengdu’s Ecological Zone (CDEZ)

|

Dimensions |

Aspects |

Chengdu Ecological Zone Characteristics |

|

SPATIAL PLANNING

|

Multi-scale and hierarchical system |

|

|

|

Dynamic and evolutionary adjustment |

|

|

SOCIO-ECONOMIC |

Synergistic Land use planning and design |

|

|

Transportation |

|

|

|

Culture/Place identify |

|

|

|

Economies |

|

|

|

ECOLOGICAL |

Capacity |

|

|

Biodiversity |

|

|

|

Ecological process and principles (suitability) |

|

|

|

Governance |

Decision making |

Driven by political leaders, supported by elitist planning professionals and experts on relevant subject matters. |

|

Implementation and evaluation |

some grass-root democracy in rural settlement redevelopment; using land markers to encourage public monitoring; lack of formal evaluation. |

|

|

Evidence, science in decision making |

GIS-based database and analysis support decision-making (mostly in technical terms); development strategies tailored toward local conditions. |

Continuous and systematic planning efforts, together with effective implementation methods in the form of development codes and government programs facilitating the desired land-use changes, have brought about successful transformation of CDEZ and turned a blueprint into reality. With the support from its home province Sichuan, Chengdu has passed a series of codes and regulations since 2012 aimed at controlling characteristics of land development inside CDEZ and protecting the spatial parameters of its open space and boundaries. By 2022, lakes, rivers, forests, and wetlands have emerged to form a natureful backdrop of this around-city territory where a 300-km greenway system, accessible by public transit, connects numerous public parks, cultural and recreational sites, and rural communities with thriving agritourist business and civic facilities (Figure 2). Having learned from CDEZ’s experiences, Chengdu plans to apply a similar approach to the smaller cities in the region, in the hope to use CDEZs to shape a desired multi-centered regional spatial structure where human habitats and natural environments co-evolve in harmony (Chengdu Municipality Government, 2018).

Results and Evaluation of the CDEZ

CDEZ stands out as an effective urban-rural linkage in several dimensions. Its achievements and inadequacies can be elucidated by checking the extent to which the plans, policies and actions behind the EZ is consistent with UN-Habitat’s 10 guiding principles. Published at the end of 2019, these ten guiding principles, accompanied with a framework for action, are the outcome of UN-sponsored, extended multi-stakeholder engagement process aimed at learning from proven strategies and experiences for creating integrated territories underlying an urban-rural continuum. These guiding principles (GP, see the list below) lay the ground for applying and adopting a globally inspired action framework to nations and regions where integrated co-development of both urban and rural communities is key to sustainable urbanization.

- Locally Grounded interventions

- Integrated governance

- Functional and spatial systems-based approaches

- Financially inclusive

- Balanced partnership

- Human rights-based

- Do no harm and provide social protection

- Environmentally sensitive

- Participatory engagement

- Data driven and evidence-based

The evaluation informed by these principles sheds light on the significance of Chengdu’s institutional and spatial approaches that have helped align governance across various levels of and achieve shared-interests among multiple stakeholders. While it is recognized as an effective tool for establishing urban-rural linkages, CDEZ does not exemplify the application of all principles comprehensively. Some guiding principles are combined to evaluate the CDEZ’s development based on its evolutionary process and in light of Chengdu’s institutional changes.

Locally grounded approaches that are human rights-based and provide social protection (GPs 1, 6 & 7)

The CDEZ emerged as a product of its unique local context, shaped by historical development legacies and driven by innovative approaches enabled by evolving institutional frameworks. The spatial delineation of the Chengdu Ecological Zone (CDEZ) did not align with natural features or ecological processes. Instead, the boundaries were defined pragmatically, reflecting the absence of precise spatial documentation regarding land users and land-use types.

According to the early years’ debate underlying the central city’s planning for the CDEZ, this territory was never intended as a static zone for environmental protection. Instead, the approach was to find effective ways to address urban expansion, rural construction, industrial development, and ecological protection simultaneously (CDIPD, 2003). Great attention was given to the improvement of rural communities’ quality of life when the CDEZ development began with preserving some vernacular rural settlements and upgrading their living conditions, and eventually aggregated other settlements into compact new villages with modern public facilities and services. Land uses supporting modern agritourism are encouraged to take advantage of local assets and opportunities. Five villages inside several wedges of the CDEZ have developed successful flower nurseries with tea houses, restaurants, and lodging, earning them the nickname “Five Golden Flowers” and becoming famous attractions for urban residents.

Not only has the outcome of land use changes in the CDEZ brought benefits to rural residents, but the process of these changes, which often involves land use integration and relocation, has been facilitated by a series of human rights-based programs and reforms. These efforts helped avoid many of the controversies and injustices typically associated with peri-urban development seen in other cities in China. Those prominent reforms and programs are summarized below.

- Huko (Residence Registration) System Reform. Chengdu started to abolish the residence registration system in 2007, which provides freedom in location choice to rural residents as they can now reside in urban areas without needed an urban residence registration. It also made access to social security and health insurance uniform between rural and urban areas. As a result, the reduced rural-urban disparities helps relieve the pressure on constant urban expansion to accommodate the influx of rural migrants.

- Clarification of property delineation and user rights and Establishment of rural land use rights exchange – Villages in Chengdu’s peri-urban area rely on direct democracy for governance. A village council on a 3-year term makes decisions on how to use communal assets, allocate available financial resources, and lead the process of delineating boundaries of a homestead site and arable land site for a household (Ye and LeGates, 2013). This governance structure helped implement a grass-root approach to surveying, mapping, clarifying, and negotiating parcel boundaries, scope of user rights, and a benefit-sharing mechanism, which had eventually created a land use right system in the rural area and allowed smooth operation of a market for land-use right exchange.

Chengdu established rural land use rights exchange based on a national policy titled “urban-rural land linking”, which allows and facilitates transfer of the land use right of rural construction land to sites inside developable urban area. By ensuring that rural communities and original land users retain the economic interest associated with lands whose land use right are traded away, Chengdu has been successful at aggregating rural parcels to support compact village construction, rearranging farmland to enable large-scale modern agriculture industry, as well as removing non-conforming land uses from inside the CDEZ. This mechanism has helped with a gradual reduction of developed area inside the CDEZ from 74 sq. km to the targeted 54 sq. km.

- Humane Programs to provide social protections. The implementation of CDEZ plan inevitably involves spatially redistributing rural population. Many human programs and development strategies have been used to ensure that the rural residents are engaged in this process on a voluntary basis and their economic interests are protected. Adequate social services, such as job training, social assistance, and basic health insurance scheme, are provided to reduce urban-rural disparities and help rural migrants adjust to changes. Those who migrate to cities to work are allowed to keep their farmland, transfer their farming rights, and lease those rights to gain economic benefits. Those who stay in the rural settlements can choose to move into new compact villages where community infrastructure and services standards have been upgraded to be uniform between urban and rural areas (Wang, 2013).

Functional and spatial systems-based approaches via Integrated governance (GPs 2 & 3)

An integrated governance system in the region has been vital to an enabling institutional context that allows CDEZ to develop into and function as a multi-functional territory to serve the entire region. Chengdu Commission for Coordinated Urban-Rural development was established in 2007 which has authority over a wide range of functions, such as urban planning and land management, construction, agricultural, transportation, water, environmental protection, human resources, health, education, and finance. The hierarchy of governments at all levels including the municipality, cities, counties and villages work together in the process to maintain vertical consistency in planning and management. Various sectors’ administrative agencies, such as water bureaus, planning agencies, land management agencies, collaborate ensure horizontal consistency.

The CDEZ’s own comprehensive plans and functional plans are embedded in a larger regional framework and coordinated with various aspects of regional development. The plans for the Chengdu region include land use, industrial base, transportation, water system, and housing development. These plans are spatially aligned with the same functional plans for the CDEZ. For example, region-wide spatial planning has been done to aggregate scattered industrial development into 13 municipal-level strategic function zones. Industrial sites previously located inside the CDEZ are relocated into other zones, allowing those sites to be converted to open space or to house public facilities. Many functional zones intersect with the CDEZ spatially, allowing the greenway system inside the CDEZ to serve as a multi-modal transportation network to support commuting to employment sites in these functional zones. Public transit services are integrated into the road network that has shaped the CDEZ’s form. There are 9 major public transit hubs within the CDEZ whose planning and placement are in coordination with rural settlement development, land use planning, and infrastructure planning within the CDEZ. Additionally, the CDEZ is a significant resource for the region’s disaster planning in responses to earthquake and climate change – 30 evacuation routes and 58 shelter sites have been integrated into the CDEZ plan (CDIPD, 2012).

Implementation of the plans also benefitted from a streamline planning process at all government levels and having increasingly detailed control plans/codes and guidelines established through collaboration among multiple sectors and comprehensive research. For example, policies governing the infrastructure construction of the CDEZ’s ecological land are required to be collectively developed by multiple agencies, including urban planning, forestry and landscape, environmental protection, and water affairs. Professional planners are assigned to rural communities to provide technique support and help devise plans and development consistent with regional objectives and standards.

Environmentally sensitive approaches driven by data and evidence (GPs 8 & 10)

Chengdu people’s respect for and capacity to handle environmental conditions have long contributed to the region’s civilization and prosperity. The region’s primary wind direction, NE 38 degree, has historically shaped the road axis in the central city’s oldest urban area and influenced its continuous expansion (Qin, 2015). The Dujiangyan hydraulic project, 55 kilometers away from the central city, still functions today like it did more than 2000 years ago to successfully control Min River’s flow volume and speed during monsoon season so that the downstream Chengdu Plain, where the central city is located, is spared of flooding. Chengdu has adopted three major development principles – 1. Environmental (esp. water) capacity should determine the region’s urbanization limit 2. Land set aside for protection, such as prime agricultural land and ecologically sensitive land, should help determine the boundaries of cities’ expansion. 3. Local climate, such as wind direction, should determine shape of urban fabric or layout. These principles translate to the a locally-tailored and environmentally sensitive approach to CDEZ’s planning and construction. More importantly, the CDEZ’s development reflects a belief that nature can be made better and more resilient by “constructing” it.

At the center of the CDEZ’s planning for “ecological cultivation” is a water resource conservation and management strategy entailing the creation of 6 large lakes and 8 wetlands connec ted with rivers and cannels. This water system builds upon existing scattered water bodies and is tasked to perform various ecosystem services, including water storage, purification, and treatment, wildlife habitat and biodiversity, food provisions, social and cultural affairs, recreation, etc. Detailed control plans over construction help ensure the system’s performance by setting height limits to create the best vistas and view sheds, requiring deep setback from lakes and wetlands, and limiting surface ratios of impervious land and landscaped areas within the CDEZ (Yin and Lu, 2013). An indicator system is used to monitor development, assisted with the use of Geographic information system (GIS) to manage land parcel and development information, as well as to analyze environmental impacts from different development scenarios. Also integrated into the ecological space is strategically placed cultural landscape that showcase the city’s historical and cultural character.

Inclusive and balanced Investment (GP 4)

Chengdu government’s willingness to make direct investment, promised to be about 300billion RMB, is critical to the CDEZ’s realization according to the plans. The CDEZ also benefitted from Chengdu’s vast amount of public investment in peri-urban area and conscious investment choices aimed at addressing urban-rural inequity since 2007. A number of targets linked to those investment choices are directly relevant to the CDEZ’s development, including improving rural built environment, developing modern agriculture, diversifying economy, and enhancing community autonomy and social services for urban and peri-urban communities (Ye and LeGates, 2013). One good example is the investment to create a regional public transit system, which bring local residents and tourists to the public parks in the CDEZ via directly subway, regular transit, and shuttle bus lines and whose transit hubs are integrated with bike-share and other micro-mobility facilities to allow people enjoy a bike-highway embedded in the greenway.

Additional investments are needed to maintain the CDEZ in the long run, which has been a challenging task for Chengdu. Several approaches are being experimented – revenue obtained from increase in land value for sites adjacent to the CDEZ, land lease income, spatial re-arrangement of development sites within the zone that can bring additional economic return.

Participatory Engagement and Balanced Partnership (GPs 5 & 9)

Like many other major large-scale urban developments in Chinese cities, Chengdu’s EZ is an outcome of a top-down process where public input and participatory engagement were limited, at least at the very beginning. While grass-root participation was crucial in the successful implementation of many of CDEZ’s plans, the vision and strategies behind the CDEZ were more or less driven by political leaders, elitist planners from the Chengdu Institute of Planning and Design, as well as experts on relevant subject matters. Chengdu’s effort to send professional planner to rural communities helps with communication and enforcement of plans and compliance. The rural community planners facilitate rural community’s planning and development by making sure local plans are consistent with the overall regional planning; but they are not advocates for local interest and rather serve as technical experts to guide local decision-making.

There is a growing effort to increase transparency in management and protection of the CDEZ. Chengdu established a land marker system to mark the physical boundaries of the CDEZ. Since 2012 over 100 markers have been erected on the ground to demarcate the boundaries of this protected ecological zone and allow public monitoring of the changes in land use following the plans. Interviews with planners involved in the process suggested changing attitude toward public involvement and additional mechanism established for that purpose.

Key Messages

This case study traces the CDEZ’s evolution as it had initially emerged as a tool to help the central city combat urban sprawl and later become a territory where comprehensive planning was carried out to support water-centric ecological improvement and urban-rural integrated development. The CDEZ’s materialization process speaks to Chengdu City’s incremental, adaptive, and experimental approach to peri-urban planning, where dilemmas arise from competing institutional goals, conflicts exist among numerous stakeholders, and implementational challenges persist due to ambiguity in the broader governance system. The case narrative highlights the fact that a regional planning approach characterized with sectorial integration and strong public engagement has shaped the CDEZ’s realization and performance.

The making of the CDEZ has benefited from the maturation of Chengdu’s urban and regional planning, as well as reforms in its broader institutional system. While the driving agents in this process have always been government agencies, which is common in China’s top-down planning regime, the involvement of a wide range of stakeholders via innovative stakeholder engagement methods, as well as the adoption of solutions identified through participatory procedures, makes the CDEZ a unique example of a regional planning approach known as “the Chengdu Model”.

Refrences

CDIPD (Chengdu Institute of Planning and Design). “Chengdu central city non-development land urban-rural integrated plan – Chengdu City 198 Zone Control Plan,” 2003.

———. “Chengdu Ecological Zone comprehensive plan,” 2012.

Chengdu Municipality Government. “Chengdu City Comprehensive Plan (2016-2035) Review Version,” 2018.

Legates, Richard, and Delik Hudalah. “Peri-Urban Planning for Developing East Asia: Learning from Chengdu, China and Yogyakarta/Kartamantul, Indonesia.” Journal of Urban Affairs 36, no. sup1 (May 2014): 334–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12106.

Lei, Lei. “‘Leafs’ to shape green ecological circle in Chengdu.” Chengdu Commercial Newspaper, August 1, 2008. http://news.focus.cn/cangzhou/2008-08-01/510904.html.

Qin, Bo. “City Profile: Chengdu.” Cities 43 (March 2015): 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2014.11.006.

Wang, Bo. “The spatial layout models of new rural communities in Chengdu City.” Planner 29, no. Special issue (August 1, 2013): 12–15.

Yang, Yizhao, Lei Zhang, Yumin Ye, and Zhifang Wang. “Curbing Sprawl with Development-Limiting Boundaries in Urban China: A Review of Literature.” Journal of Planning Literature 35, no. 1 (February 2020): 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412219874145.

Ye, Yumin, Richard LeGates, and Bo Qin. “Coordinated Urban-Rural Development Planning in China: The Chengdu Model.” Journal of the American Planning Association 79, no. 2 (April 3, 2013): 125–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2013.882223.

Yin, Hang. “A Green Necklace for Chengdu: Ecological Zone to Be Completed by 2020.” WCC Daily. April 12, 2016. http://scnews.newssc.org/system/20160412/000664408_2.html.

Yin, Jie, and Daming Lu. “Research on Control Methods of Spatial Form of Development in Large-Scale Urban Ecological Areas.” Planner 29, no. Special Issue (August 1, 2013): 16–19.

Zeng, Jiuli. “Exploring the Spatial Control of Chengdu Ecological Zone.” Presented at the World City Day 2017 – Shanghai Forum, Shanghai, China, 2017. www.sohu.com/a/206893444_747944.

Author's profile

Yizhao Yang, Ph.D., is a Professor at School of Planning, Public Policy and Management, University of Oregon. Her research interests focus on the relationships between the environment and people’s behavior and wellbeing. She also studies global sustainable urban planning and design, particularly in countries in East Asia, with an aim to explore how place-making knowledge and practices can be transferrable between different cultures and countries.

This case study is adapted from the publication Evaluating the United Nations Habitat Guiding Principles for Urban-Rural Linkages: A Case Study of Chengdu by Padgett Kjaersgaard, S., & Yang, Y. (2022). It appears in Y. Yang & A. Taufen (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Cities and Landscapes in the Pacific Rim, published by Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.