Capacitating Philippine Indigenous and Local Institutions and Actualising Local Synergies on Restorative Ridge-to-Reef Biodiversity Conservation for Food Security and Livelihoods (SITR8-12)

22.03.2024

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

Daluhay Daloy ng Buhay Inc.

DATE OF SUBMISSION

19/09/2023

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Philippines

AUTHOR(S)

Mark Edison R. Raquino

Marivic Pajaro

Jagger E. Enaje

Reymar B. Tercero

Teodoro G. Torio

Paul Watts

LINK

1 Introduction

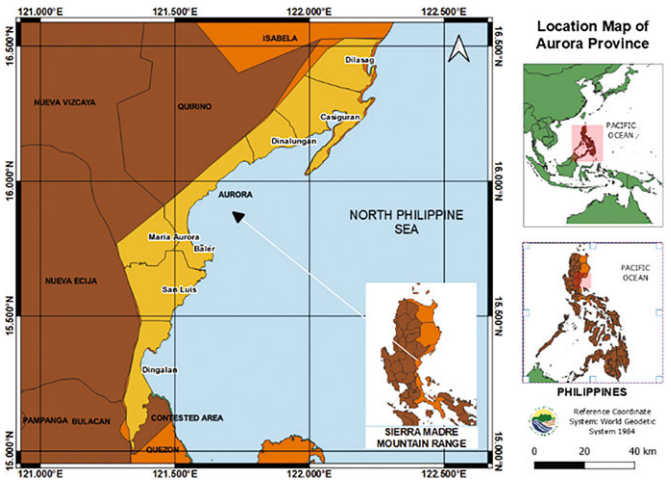

The institutionalisation strategy of the localised and programmatic restoration component is further validated through the use of resilience assessment. Restoration of socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS) can be directly linked to the assessment of system resilience (UNU-IAS et al. 2014). In Aurora Province, Philippines (Fig. 13.1; Table 13.1), coastal food security and livelihoods are affected by localised actions on forest, agricultural, and marine ecosystems within the Sierra Madre Mountain Range (SMMR) and the North Philippine Sea (NPS) marine bioregion (Watts et al. 2021). The SMMR, a recognised biodiversity corridor, represents the country’s longest mountain range that contains the largest remaining cover of old-growth tropical rainforest harbouring endemic and critically endangered species (Ong et al. 2002). The SMMR is home to some of the most ecocentric Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) in the country. Aurora’s globally significant rainforests at the centre of the SMMR are traditionally managed by Indigenous Dumagat, Alta, Agta, and Egongot communities that are determined to hold on to their culture, biodiversity heritage, and distinct ethnoecology. Marginalised fishing communities have settled along the coastline of Aurora; although primarily engaged in fishing, they are secondarily engaged in subsistence farming. These migrant settlers have now blended with the abovementioned Indigenous communities, making up the IPLCs. It has been suggested that recognition of local institutions, knowledge, and tenurial rights produces effective conservation when it enables collective local environmental stewardship, which is dependent on social and political factors, including food security and support for livelihoods towards community resilience (Dawson et al. 2021).

This chapter considers reversing the trend of biodiversity decline through restoration of a globally significant area, as well as linked assessments and actions on both sociological and ecological factors. Critically, IPLC conservation efforts are harmonised with existing governance strategies by other local and national agencies. Several researchers have argued that IPLCs can be more than passive recipients of restoration activities as they have the historical reference and can therefore play more active roles in restoring ecosystems (Uprety et al. 2012). Direct involvement of IPLCs is perceived as important not only because it makes conservation more equitable, but also because it has the potential to produce more effective resource management and better biodiversity outcomes (Garnett et al. 2018). While this is the case for many IPLCs across the globe, legal and institutional empowerment and support for local institutions are still lacking. The pathways along which the role of IPLCs and characteristics of governance interact to produce different social and ecological outcomes have not been well explored, precluding a common understanding of these dynamics (Ferraro and Hanauer 2015). Harmonised governance strategies that prioritise IPLCs and empower them to contribute to long-term stewardship and effective conservation require approaches that enhance local capacity for management, planning, and governance as attributes of resilience. The ridge-to-reef approach, including watersheds, agricultural lands, and marine ecosystems, encompasses interconnected social-ecological systems of natural and human resources taking into account the social, political, economic, and institutional factors affecting these systems (Katusiime and Schutt 2020). Watersheds descending from the SMMR irrigate thousands of hectares of life-giving farmlands, also providing both drinking water and hydroelectric power to the surrounding communities and provinces. These areas are a source of food, medicine, and livelihoods, as well as timber and non-timber products that help fill the demand for building materials, handicrafts, and furniture. The degradation of natural resources and biodiversity due to deforestation, conversion of the forest through unsustainable slash-and-burn farming techniques, wildlife hunting, charcoal making, unsustainable practices of harvesting timber and non-timber forest products, and poor governance can negatively affect dependent communities’ food, health, and overall well-being (Golden et al. 2016; Pecl et al. 2017). Therefore, safeguarding and restoring ecosystems is often critical to support IPLCs’ resilience and well-being (Sangha and Russell-Smith 2017).

IPLCs are considered as a focus of this case study, and where Indigenous groups are concerned, the study is based upon prioritising the goals of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP 2013) that the Philippines has agreed to. Emphasis was also placed on activities that promote synergy and shared leadership between IPLCs as an approach to optimise community resilience. The pathways and processes presented in this case study further outline the everchanging local SEPLS and how localised systems, including the IPLCs, deal with change and continue to develop. This chapter also recognises the significance of Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) as critical information for restoring biodiversity, such as identifying restoration areas with the appropriate native species or cultural keystone places (Uprety et al. 2012; Cuerrier et al. 2015), both in terrestrial and in marine environments (Comberti et al. 2015). Further, ILK assists residents in withstanding shocks and disturbances and in using such events to catalyse renewal and innovation. However, enhanced community and ecosystem resilience are also important to meet increasing challenges facing ridge-to-reef ecosystem services and to ensure sustainable production systems. While these actions and goals are local, this case study is also intended to contribute to both global sustainable development objectives (UNU-IAS et al. 2014) and biodiversity targets (Tobón et al. 2017).

The objective of this chapter is to demonstrate how capacitating IPLC to implement a collaborative inter-community approach to institutionalised restoration activities can advance community-based resilience. The case study highlights the contribution of IPLC to biodiversity conservation and how inter-community synergies can optimise resilience and resources towards meeting larger spatial planning requirements (Strassburg et al. 2020) for ecological restoration. We also look into the complex pathways through which good governance qualities affect IPLC in the presence of enabling mechanisms and institutional factors that can empower stewardship actions with effective conservation outcomes.

2 Methods

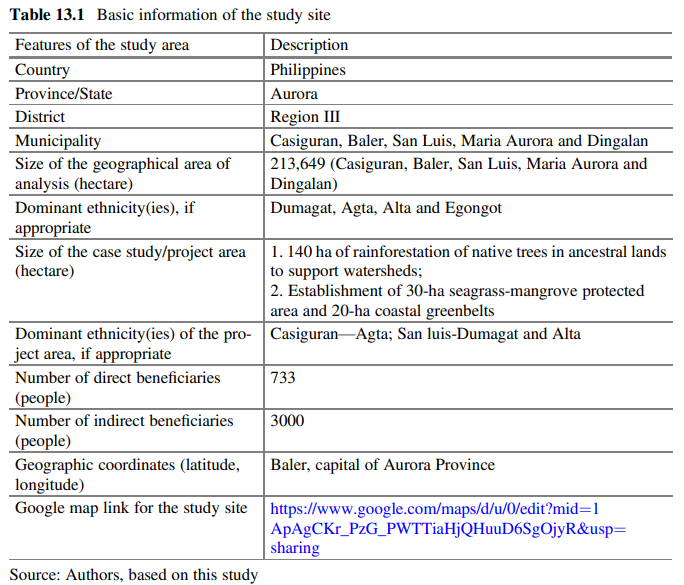

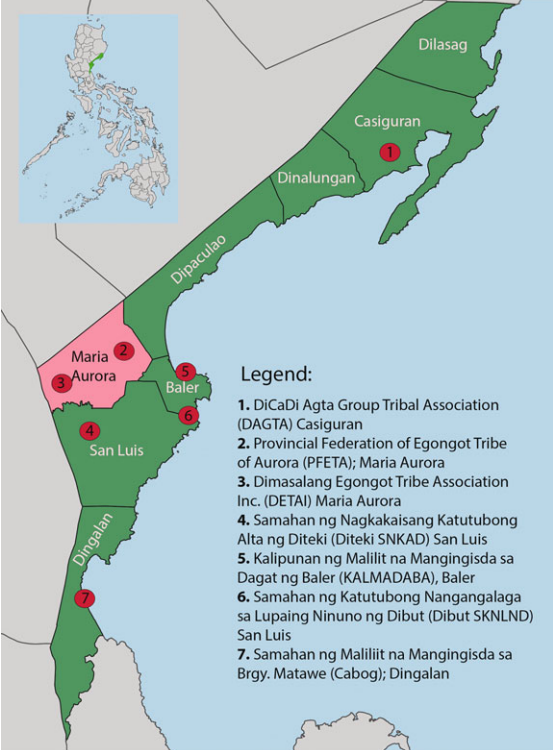

The case study presented herein is based on a 2016 project implemented by the non-governmental organisation, Daluhay – Daloy ng Buhay, Inc. (Daluhay), on capacitation of Sierra Madre Indigenous and Artisanal Communities with support from the Global Environment Facility’s Fifth Phase of the Small Grants Programme (SGP5). Seven IPLCs were selected as part of this project across five municipalities of Aurora Province. The organisations in the IPLCs were composed of two fisherfolk and five Indigenous communities from Egongot, Dumagat, Alta, and Agta communities. These communities expressed their interest in taking part in the initiative on community-based biodiversity conservation, having minimal experience in project implementation and financial management. For the Indigenous Peoples Organisations, a free, prior and informed consent was obtained from the Indigenous communities. The SGP5 initiative in Aurora Province concluded in 2018, but continuing initiatives after 2018 were considered in the results and discussion as some of the IPLCs scaled out their efforts.

2.1 Institutionalisation and Capacitating the IPLCs

The seven IPLCs (Fig. 13.2) were selected on the basis of having organised associations through other projects and being institutionalised by acquiring a legal personality through registration with a government entity such as the Department of Labor and Employment or the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Two of the seven IPLCs are fisherfolk organisations (i.e. KALMADABA and Cabog), while five are Indigenous Peoples Organisations, or IPOs (i.e. DAGTA, PFETA, DETAI, SNKAD, and SKNLND, see Fig. 13.2).

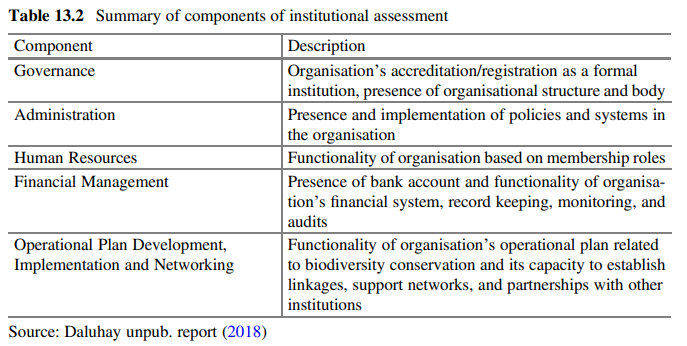

Capacity-building trainings and workshops were conducted for the selected community associations between 2016 and 2018 through SGP5. The trainings and workshops were focused on five components, which were later used in institutional and resource management effectiveness monitoring and evaluation (see Table 13.2).

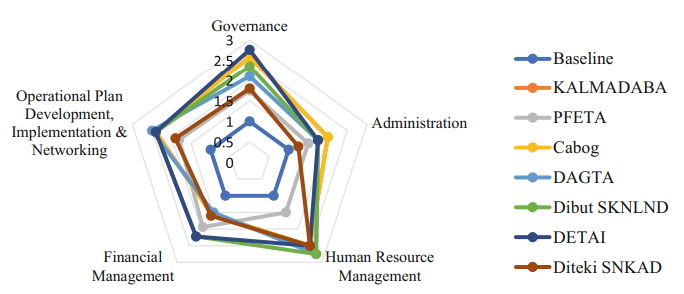

Institutional Assessment and Analysis

An institutional assessment was conducted to determine the current capacity of the seven community associations. It was administered before and after the capacitybuilding interventions were conducted. The initial assessment conducted before the training served as the baseline from which the progress of the associations was tracked after subsequent interventions during SGP5 project implementation. The assessment was conducted through a focus group discussion with the officers and members of the associations, emphasising five key components: (a) governance, (b) administration, (c) human resources, (d) financial management, and (e) operational plan development, implementation and networking, as presented in Table 13.2.

The associations were assessed before and after the intervention using a Likert scale of 1–3, where 1 is lowest with little capacity, 2 middle, and 3 is the highest score. Depending on the components, several scenarios were stated in the assessment corresponding to the Likert scale. To assess any significant change brought about by capacity building, assessments were conducted for the organisations prior to trainings and again after the trainings. The Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, which is a non-parametric statistical test that determines if two measurements of the same dependent variables have significantly changed given different conditions, was employed (Taheri and Hesamian 2013). To analyse the result of the assessment, the trial version of IBM SPSS software was used.

2.2 Actualising Local Synergies on Restorative Ridge-to-Reef Biodiversity Conservation for Food Security and Livelihoods

Ecosystem Restoration and Protection

Forest ecosystem restoration initiatives were carried out by all seven IPLCs through the community associations by planting native trees (i.e. rainforestation) within their degraded ancestral forests (for the Indigenous communities) or degraded mangrove and beach forest ecosystems (for the fishing communities). Utilising Indigenous or local knowledge, the IPLCs determined which native trees were to be outplanted in denuded forests, and wildlings were collected following trainings on nursery establishment and rain forestation techniques. The wildlings were potted and placed inside growth chambers for at least 3 months before outplanting in designated rain forestation areas. Monitors were assigned by each association on a rotation basis to check on the health of the wildlings and record mortalities in the growth chambers for replacement as necessary.

Linking different marine, agricultural, and forest ecosystems to help recover biodiversity was also undertaken via local government-declared and locallymanaged protected areas as a form of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs). The OECMs in the IPLCs were initiated through the engagement of community associations, key local government officials, and the provincial Technical Working Group (TWG). Participatory resource assessments for coastal and agricultural ecosystems were conducted, after which community validation of the resource assessment results was performed. Later, a multi-stakeholder community working group was created to take the lead in the planning process for the formulation of a management plan for the locally managed network of protected areas.

Food Security and Sustainable Livelihood Development

The IPLC partners working on food security and sustainable livelihood development adhered to three elements in their initiatives: (1) ecological—with focus on conservation of biodiversity and sustainable use of biological resources; (2) economic— ensures that the enterprise is viable, sound, and sufficiently broad-based to create wealth, value, and positive returns benefiting the community, local government, and biodiversity; and (3) equitable—emphasising equal sharing and access to benefits by men, women, the Indigenous communities, and all other stakeholders in all economic activities. Whenever appropriate, the previously-mentioned participatory resource assessment results generated in relation to restoration efforts were utilised in the identification of sustainable livelihood interventions. As needed, relevant skills training for the identification of potential sustainable livelihoods and products (e.g. ecotourism, handicrafts, fish processing, and herbal medicine production) and formulation of project proposals and business plans were provided through the support of national government agencies and non-governmental organisations. Documentation of relevant local knowledge, skills, and practices was facilitated to support preservation of Indigenous culture and traditions through a skill transfer training held by elders and targeting the youth. This training was led by PFETA, whose aim was to provide guidance in establishing the Egongot Village as a potential eco-cultural tourism destination.

Networking and Building Linkages

To consolidate and scale up the SEPLS initiative in Aurora Province, Daluhay, with the community associations, shared best practice experiences and learnings during province-wide trainings and workshops. Daluhay also made efforts to build its directory of contacts, particularly with other civil society organisations, academe, local government units (both from within the province and neighbouring provinces and surrounding municipalities), potential funders, and national government agencies. These efforts are focused on scaling up the ridge-to-reef approach (Alejos et al. 2021) and professionalising Philippine Coastal Resource Management skills (Pajaro et al. 2022; 2013), within the biodiversity land corridor and marine bioregional considerations (Watts et al. 2021). These contacts were shared with partner IPLCs, providing them with opportunities to forge links with the network whenever relevant for them. These linkages are critical, particularly for policy advocacy and scaling up and scaling out of activities.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Institutionalisation and Capacitating IPLCs

The Daluhay facilitation and institutionalisation paradigm described in part herein, involves a reflexive focus on sustainability-gaps up through all levels of cultural mandate and stakeholders, project by project, often involving tens of “communities of interest” within specific geographic boundaries. The institutionalisation phase of the current project included the process of establishing organised groups in IPLCs, was important as this is when the community associations were formed with the aim of being permanent and publicly recognised entities. The associations could then have a legal personality and begin to build their track record in project and financial management. Recognising the diversity of cultures with the selected IPLCs, Indigenous political structures needed to be considered in establishing organisational management systems in the case of the Indigenous communities. This initial step was greatly supported by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples. In the case of the Egongot IPLC, clan representation needed to be ensured and considered in the selection of leaders.

While each community-based association in this study exhibited strong leadership and specific skills, emphasis was placed on building capacity through activities that not only strengthened the organisations themselves, but also promoted synergy and shared leadership between organisations. The trainings were held simultaneously for all IPLC partners, which optimised resources, but at the same time opened up opportunities for collaboration and synergy. For example, the trainings on environmental law enforcement led to a consolidated plan based on shared resources and coordinated actions among the IPLCs.

Institutional Assessment and Analysis

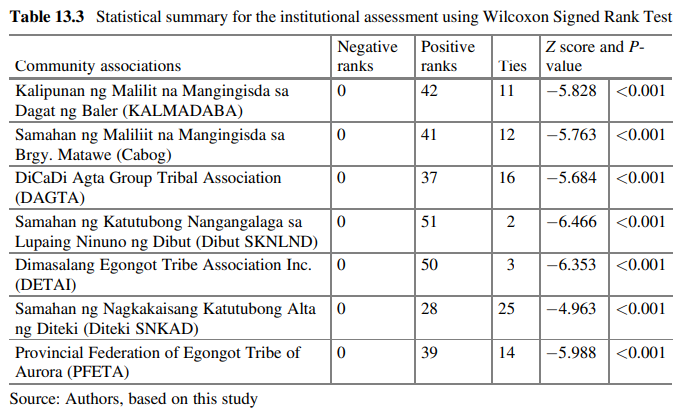

Involving multiple communities in training and activities led to associations and individuals taking leadership roles on specific topics and tasks. The associations’ progress in building their capacities was assessed and tracked to help determine what further trainings they would need. Results of the assessment indicated the increased capacity of the community associations in the five components from the baseline (Fig. 13.3). The spider graph shows the mean values that demonstrate the improvements of the seven IPLC associations after the capacity-building trainings. Increased capacities were demonstrated for all five areas of assessment, each representing enhanced resilience to deal with current and future challenges. The widest range of change in capacity was found in the area of human resources, while financial management had the tightest array. Each of the IPLCs had a unique capacity growth profile (Fig. 13.3), representing the need for individualised planning for future activities through facilitated action research cycles (Watts and Pajaro 2014)t improve resilience.

The effectiveness of the capacity-building trainings in strengthening the community associations in the five components is further supported by the increased ratings generated by the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test (Table 13.3). The positive ranks indicate a general increase in rating from the baseline for each of the components, although there were tied scores in some components of the assessment, i.e. they remained the same. The high absolute values of the Z scores resulted in low Pvalues, which describe the probability of the changes being random (Table 13.3). These results indicate that the capacities of organisations after training and capacity building were significantly higher than before the training and that community resilience was enhanced.

The IPLCs allowed the communities through the association leaders to participate in several capacity-building activities and in turn facilitated the members to act together and benefit from the opportunities. For example, being able to manage finances in a transparent way and report on them to the scrutiny of the members was a new and useful experience for communities. All except one of the seven partner IPLCs had never opened a bank account. Submitting documents on their work and financial plans and reports, even if written in the Filipino dialect, was a struggle for IPLC project partners, but a huge accomplishment contributing to future efforts on building resilience. The said documents were required for the IPLCs’ budget allocations to be released, according to the agreed terms. Towards the end of project implementation, agreements and plans on how their organisations could continue what they started became critical points of discussion. Of the IPOs with stronger leaders, Dibut’s SKNLND was able to use members’ contributions as capital and with further guidance, set up a store which sold basic commodities to its members at a very affordable cost. Another organisation, DETAI, reorganised as Dimasalang Egongot Tribe Farmers and Weavers Association, Inc. (DETFAWAI) in 2019 and registered with the SEC. Subsequently, having built a track record for successful project management, the organisation submitted proposals and was approved for funding amounting to 2.7 million PHP (US$47,000) from the Forest Foundation of the Philippines, as well as one million PHP from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to implement projects on biocultural heritage, protection and conservation of the ancestral domain, and to support its weaving industry.

Through the various capacity building activities implemented, the IPLC associations strengthened their legal and institutional status, thereby establishing track records with which to access future funding opportunities. Legal status allowed them to establish internal rules and policies that are relevant and connected to their culture and values. The Indigenous communities ensured that clan representation was secured during the selection of leaders with the approval of the tribal council and elders. For the fisherfolk, selection of leaders depended on active participation and knowledge of fisheries resources, which are important for leaders to establish authority and respect and to effectively lead collective action towards conservation. Good governance starts with selecting community leaders who go through the proper selection process with culture and traditions as the foundation. Recognising these customary institutions is said to further promote the understanding of restoration efforts and therefore increase local participation (e.g. Wehi and Lord 2017; de Koning et al. 2011). This process is also important for an association’s accountability and conflict management.

The capacity building conducted over the span of 2 years (2016–2018) also provided the IPLCs with mechanisms to improve their internal systems in administration, human resources, and financial management. While some aspects of the institutional assessment values stayed the same, showing the need for further training and monitoring, the associations nevertheless grew significantly from their baselines. This growth has further strengthened the foundations for their rights and participation in local decision-making. They were recognised by external institutions, both from the government and private sectors, for future partnerships and collaborations. The Egongot IPLC through DETAI and PFETA were able to secure other funding to continue their conservation and restoration work within their ancestral domains. In addition, KALMADABA, DETAI, SKNLND, and SNKAD were able to partner with the national agency, DENR, for scaling up efforts in restoration through the National Greening Project. These capacity development activities potentially increased the resilience of the IPLCs by preparing them to proactively respond to future challenges, such as those emerging from climate change.

3.2 Actualising Local Synergies

Ecosystem Restoration and Protection Efforts

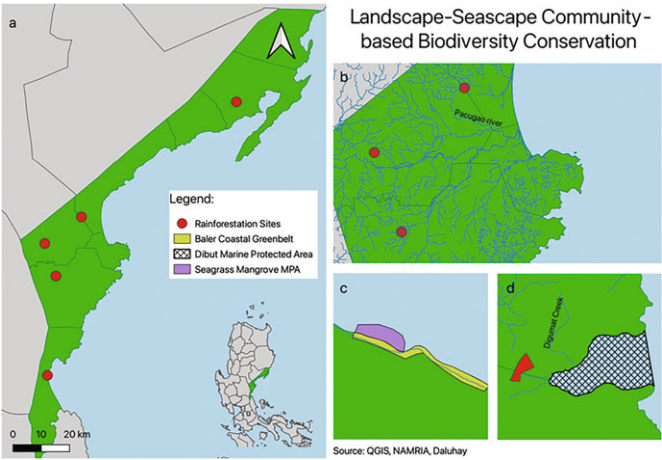

The trainings undertaken by the IPLCs on biodiversity conservation, nursery establishment, ecosystem restoration, and natural resources management eventually contributed to: (1) reforestation of 140 ha of denuded ancestral lands to support watersheds (Fig. 13.4a, b), where at least eight threatened endemic forest species were outplanted; (2) establishment of a 30-ha seagrass-mangrove protected area and 20-ha coastal greenbelt (Fig. 13.4c); and (3) updating the marine protected area management plan for the ancestral waters of San Luis (Fig. 13.4d).

These community-based restoration activities led by the IPLCs were catalysed by partnership with the provincial Technical Working Group (TWG), whose multiagency members include representatives of an NGO (Daluhay), municipal and provincial local governments, national agencies (DENR and BFAR), and the academe (Aurora State College of Technology), with funding through SGP5. In Baler municipality, the participatory coastal resource assessment (PCRA) of the seagrass and mangrove area led by the KALMADABA fisherfolk association became the basis for the establishment and later adoption of a municipal ordinance designating mangrove-seagrass conservation management zones, including the protection of Kandelia candel, a rare mangrove species. Follow-up PCRA monitoring in 2018 indicated some improvement based on the recorded presence of the commercially valuable chiton mollusc, which was previously absent in 2016.

There were also restoration efforts led by the local government unit (LGU) through the Municipal Agriculture Office but still catalysed by the provincial TWG. In San Luis municipality, the LGU provided the funds and invited the IPLC to join in the participatory resource assessments of coastal and agricultural ecosystems. The proposed coastal management zones and prescriptions were presented to the community for recommendations and endorsements. These were then incorporated in the draft management plan and became the basis for a municipal ordinance. Efforts to create a model ridge-to-reef approach to biodiversity conservation led to the establishment of marine protected areas as OECMs. The establishment of an agricultural protected area (APA) was also initiated by farmers practicing a “pure” or mixed method of organic and synthetic farming. APA zones have been identified and were included in the proposed ordinance presented to the Municipal Agriculture Office for endorsement and to the Environment Committee chair of the Sangguniang Bayan (municipal elected council).

These efforts led to the formulation of a management plan for a network of locally managed marine protected areas covering 418 ha of coral reef (inclusive of the ancestral waters mentioned in Fig. 13.4d), 10 ha of marine turtle nesting area on the beach, and 6.56 ha of seagrass conservation zone. Another 18 ha of agricultural land, promoting biodiversity-friendly technologies, was proposed for establishment. The results of a fish catch monitoring survey in 2017 indicated that catch appears to have increased from 26 kg in 2015 to 32 kg on the average (n = 224), suggesting the positive effect of the efforts by the municipality and its partners to augment declining fish catch and potentially increase the income of San Luis fisherfolk. The farmers involved practiced conventional farming, but were also partly advocating the use of organic fertilisers and biodiversity-friendly pesticides. Of note, they claimed that it was not commercially profitable to fully practice the more sustainable farming methods. The IPLCs’ local stewardship, resource use allocations, and protection from threats within the framework of their formulated resource management plans, as well as their organisational work and financial plans, also contributed to effective conservation. The connectivity of ridge-to-reef ecosystems and among the IPLCs added value by bringing a wider coverage of restoration and enforcement. Restoration in the watersheds (Fig. 13.4a, b) greatly affected the health of freshwater and marine ecosystems (Fig. 13.4c, d). Efforts to establish marine protected areas and coastal greenbelts also provided protection to upland communities and agricultural areas. The complementation of conservation efforts is crucial for community resilience in areas prone to typhoons and calamities, such as Aurora Province. Social inputs (traditions, values, and culture) are complemented by scientific inputs in biodiversity assessment and monitoring as part of the IPLC capacity building in resource management, strengthening the socio-ecological ecosystems and ethnoecology (Watts et al. 2021). Conservation and protection of the intertidal zones, where women and children usually gather seafood, provides a model for OECMs on optimising food security, improving water quality, and improving maternal nutrition (Alejos et al. 2021).

Food Security and Sustainable Livelihood Development

There are other enabling mechanisms arising from capacity and restoration efforts that are important for both social and ecological outcomes, food security, and livelihood development. Together these efforts critically enhance socio-ecological resilience, encompassing both ecocentric and anthropocentric parameters, steps forward in actualising an Ecohealth balance between the ecosystem approach to health and the health approach to ecosystem (Watts et al. 2015). In San Luis, the LGU has acknowledged that the strong technical support provided by the project allowed it to win a major prize in the Malinis at Masaganang Karagatan competition, sponsored by the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, a national agency. The prize, in the form of livelihood funds, was also based on the results of the socio-economic and biophysical profiling conducted through SGP5. It became apparent that deep sea fishing was being monopolised by big commercial fishing operators who were mostly based outside of San Luis, an illegal encroachment on municipal waters. At least five of the nine commercial vessels had deployed fish aggregating devices (FADs) within the 15 km from the shoreline boundary of the municipal waters, where supposedly no commercial fishing should be allowed. Moreover, each fish aggregating device was placed at an average of only 4 km apart, thus altering the entire coastal ecosystem. This is a cause of concern throughout the municipal waters of Aurora Province, as reported by other coastal municipalities. This concern also ties in well with the initiative that collaborates with the Marine Resource Environment Foundation (MERF), also a SGP5 grantee, which aims to establish a North Philippine Sea (NPS) bioregional network, encompassing an assemblage of biodiversity that support fisheries critical to the food-security of more than ten million Filipinos, as well as undetermined local livelihood revenues. The NPS is highly dependent on pelagic or offshore fishery and the MERF project has looked into nearshore and offshore linkages that may require more policy research. The mayor of San Luis subsequently sent letters to the concerned commercial fishing vessel operators, warning them of their violation. Also, to address this inequitable access to deep sea fishery resources, the artisanal fishers have decided to form a cooperative and venture into sustainable fishing as a social (group initiated) and biodiversity-friendly enterprise.

Another of the IPLCs, a community association partner (i.e. PFETA— Table 13.3), has initiated the construction of a demonstration tribal village to showcase the traditional Egongot house and function hall. The function hall is also planned to serve as a mini museum that will house traditional tools/implements, instruments, and apparel. A brochure has been prepared to document different techniques in building the traditional Egongot house and the cultural meaning of the structures, as well as weaving and crafting traditional implements, instruments, outfits, and accessories. The use of herbs to treat some ailments is also a known traditional practice. Herbal products such as lagundi prepared as cough syrup and malunggay leaves as vitamins were produced as a potential income-generating venture that demonstrated traditional medicines used by ancestors. The documentation of Indigenous knowledge, systems, and practices, and the construction of a heritage village showcasing the unique culture of the Egongots, has inspired other Indigenous community leaders from other IPLCs engaged in the project to replicate the same concept in their areas as a way of preserving their heritage. In further examples of inter-community synergies, chieftains of the Egongots in other settlements (e.g. Dipaculao and Dimasalang) are considering similar demonstration villages with museums in their communities as part of their future plans. In this instance, cultural and biodiversity heritage played an important role not only in the process of co-designing restorations efforts and management plans but also for food security and livelihoods.

Networking and Linkages

Scaling up of SEPLS initiatives is a crucial strategy for a sustainable planet, requiring expansion of contacts outside the jurisdictions of the IPLCs. However, linkages within the same locality of the IPLCs should continue to be built and strengthened. The project advanced the landscape and seascape approach as it expanded its reach to cover the whole stretch of Aurora Province and beyond, embracing the other provinces along the North Philippine Sea through MERF, another SGP5 grantee. In Aurora Province, Daluhay has maintained close linkages with the IPLCs through their LGUs, particularly the Municipal Environment and Natural Resources Offices and/or the Agricultural Offices. Decadal Daluhay facilitation of provincial-level collaboration led to the establishment and active involvement of the provincial Technical Working Group (TWG), engaging academe, the provincial local government (Environment and Natural Resources and Provincial Agriculture Office), and national agencies including the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) and the Department of Environment Natural Resources (DENR). The TWG played a crucial role in strengthening the IPLCs as it provides collaborative technical support. This has allowed LGUs from different municipalities to have easier access to technical expertise, which is required when establishing protected areas and OECM initiatives. Whenever possible, Daluhay also facilitated inter-community communication and event planning to promote exchange between the IPLCs. This approach enhanced resilience through shared leadership. Some communities were stronger in specific capacity building activities and were able to facilitate a broader sense of community around shared socio-ecological goals. Recognising that future action research cycles would first require establishing the next step priorities for each IPLC, further multi-IPLC projects have great potential to optimise both available resources and resilience enhancement.

Partnership with the provincial TWG and funding support from the SGP5 assisted in determining long-term goals and achieving short-term goals. The technical and financial support provided the necessary incentives for the implementation of restoration efforts and establishment of networking strategies by the seven IPLCs. Local policy frameworks are crucial for maintaining restoration efforts and further strengthening the IPLCs, as well as inclusion of conservation efforts in the economy through payment for ecosystem goods and services. The efforts of the IPLCs and TWG have led to institutionalised local policies: the Baler seagrass-mangrove protected area and the San Luis network of marine protected areas. In addition, a draft provincial resolution in support of the IPLC network that includes recognition and support for Indigenous Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs) has been submitted to a provincial councillor for sponsorship.

The SGP5 project also provided opportunities for community associations to closely collaborate with other SGP5 grantees outside of Aurora Province belonging to the Lower Sierra Madre Hub. These included the Bagong Lumad Artists Foundation, Inc. (BLAFI) and MERF. BLAFI worked with IPLC partners using social artistry as a tool to document local knowledge, systems, and practices related to biodiversity conservation. This documentation has been compiled into a collection of original song compositions in an album called Awit ng Aurora (see https://sites.google.com/a/blafi.org/main/awit-ng-aurora-album). Meanwhile, work with MERF allowed for expansion of the network to include the ten provinces around the North Philippine Sea and taking the lead in advancing the socio-economic concerns of stakeholders around the newly claimed offshore Philippine territory, the Benham Rise.

The efforts previously outlined in Sect. 13.3.1 on institutionalisation and capacitating IPLC, as well as Sect. 13.3.2, actualising local synergies, can be used to assess community resilience within the SEPLS framework. Due to the limited nature and scope of the activities implemented within the SGP5 project cited in this case study, we were able to assess only 17 of the 20 indicators described in the SEPLS resilience toolkit (UNU-IAS et al. 2014). The three indicators that were left out have been acknowledged as significant research gaps. These were: (1) diversity of local food system, (2) maintenance and use of local crop varieties and animal breeds, and (3) human health and environmental conditions. At the time of writing this chapter, we are filling these gaps by working with the IPLCs on a maternal ecohealth (Alejos et al. 2021) project considering sustainable community-based food systems, supported by the Satoyama Development Mechanism and the Aurora Provincial Health Office. A systematic resilience assessment using the UNU-IAS et al. (2014) toolkit was not considered as the two initiatives evolved simultaneously. For integrated planning and policy development, it would be appropriate to conduct focus group discussions with IPLCs when the opportunity arises.

4 Conclusions

Complex pathways and dynamic interactions persist between human culture and traditions and diverse ecosystems as experienced with the seven IPLCs in Aurora Province. To ensure sustainable ecosystem goods and services from these diverse ecosystems, a balance between production, conservation, and management should be maintained across the landscapes and seascapes, scaling up more localised ecohealth balance (Watts et al. 2015). The SGP5 implementation experience in Aurora Province demonstrated the significance of IPLCs as local institutions that can advance effective stewardship efforts in restoration of SEPLS through several traditional activities. These include sustainable self-regulation of resource use; habitat restoration; assertion of territorial rights; resistance to external extractive pressures; and the maintenance of stewardship practices under environmental, economic, and political change.

The various knowledge, skills, and experiences imbibed by IPLC project partners, Daluhay, the TWG, and the leaders of organised associations led to advancements in local management, planning, and resilient governance. These strategies are being used as an integral component of a nationalised effort to certify and institutionalise socio-ecological (Coastal Resource Management) skills (Pajaro et al. 2022); potentially leading to an international accord. In part, these efforts are being continued through an ongoing project with Saskatchewan Polytechnic University in Canada, working on micro-certification with Indigenous and artisanal communities in both countries. International competency accords have been instrumental in advancing institutionalisation within other fields, for example Engineering (Accord 2013). A similar action research result of establishing an accord for socio-ecological production system skills competency could help to expand global resilience. It is expected that monitoring will demonstrate increased social resilience with regard to planning and implementation based upon financial and human resource governance and administration (Fig. 13.3), leading to enhanced ecological resilience from restoration activities. The harmonised approach to socio-ecological resilience enhancement also served to break down barriers between communities and other governance agencies. This was a direct result of project synergies across communities and facilitators, such as those engaged in the province-wide TWG. The development of contacts by key community leaders supported collaborative efforts and was enhanced by participation in national-level conferences with SEPLS breakout sessions, such as the Lower Sierra Madre Hub, providing networking opportunities and the creation of broader more inclusive points of view connected to a national and international common framework. Reviewing and characterising project status, learnings, and challenges in the larger inter-community group helped in the organisation of consolidated actions based upon consensus. Further, these interactions and inter-community synergies met the goals of expanding ecosystem outcomes across jurisdictions, while maintaining the local integrity of each community group.

This case study demonstrates the key finding that embedding empowered local institutions and enabling mechanisms in conservation governance can lead to positive conservation outcomes through harmonised agendas and mandates. Likewise, the case study indicated that consideration and understanding of ILK, values, and political structure, and acknowledgement of their potential contributions to current ecosystem management regimens, are crucial for effective stewardship. Decision-making and conflict management processes are greatly affected by the IPLCs’ progressive leadership, social ties, and norms. These underscore the most important social factors supporting attainment of positive conservation outcomes. The relevance of these social inputs demonstrated in this study support the idea of incorporation in national and regional policies through integration across scales of governance, local and national development plans. Formal recognition of IPLCs and incorporating ILK, strengthens IPLCs’ legitimacy and enhances participation from community members, thus providing potential for more equitable and effective conservation. Local dependency on natural resources also puts them on the frontline in recommending appropriate SEPLS conservation and management measures. Government agencies, NGOs, and private organisations clearly still have individual roles to play in conservation, yet those roles may be constructively reoriented towards facilitation, supporting local capacity, and as a catalyst for scaling up of governance, while making efforts to understand local institutions cultural dynamics. These approaches can present cost-effective models of governance that deliver multifold benefits, supporting nature as well as social systems, equity, and accountability.

The capacity and subsequently the resilience of the seven IPLCs was expanded, resulting in more positive social and ecological outcomes through a harmonised management regimen. The project also provided a foundation for longer-term contributions to conservation and ongoing support for community resilience. In the Philippines context, this approach to broad province-based communication and cooperation towards biodiversity conservation and restoration with IPLCs can hopefully serve as a model and have a synergistic effect upon other biodiversityrich provinces bordering the Sierra Madre Mountain Range, the North Philippine Sea, and beyond.

Acknowledgements The results of the case study discussed herein were made possible by the dedication and enthusiasm of the Daluhay team, partner Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, critically, the municipal local government offices, based upon their Philippine mandate, as well as the Provincial Government of Aurora and national agencies including the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, and the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples. The strategic project was awarded to Daluhay through the Global Environment Facility’s 5th Operational Phase of the Small Grants Programme with the United Nations Development Programme as the implementing agency.

References

Accord Washington. Sydney Accord, and Dublin Accord (2013) Graduate attributes and professional competencies, international engineering alliance

Alejos SF, Pajaro MG, Raquino MR, Stuart A, Watts P (2021) Agricultural biodiversity and coastal food systems: a socio-ecological and trans-ecosystem case study in Aurora Province, Philippines. Asian J Agric Dev 18(2):12 pp

Comberti C, Thornton TF, de Echeverria VW, Patterson T (2015) Ecosystem services or services to ecosystems? Valuing cultivation and reciprocal relationships between humans and ecosystems. Glob Environ Chang 34:247–262

Cuerrier A, Turner NJ, Gomes TC, Garibaldi A, Downing A (2015) Cultural keystone places: conservation and restoration in cultural landscapes. J Ethnobiol 35:427–448

Daluhay Daloy ng Buhay, Inc (2018) Synergistic and ecocentric capacitation of Sierra Madre’s Indigenous and Artisanal Communities. Unpublished Terminal Report, Submitted to UNDPGEF SGP5

Dawson NM, Coolsaet B, Sterling EJ, Loveridge R, Gross-Camp ND (2021) The role of Indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecol Soc 26(3):19

de Koning F, Aguiñaga M, Bravo M, Chiu M, Lascano M, Lozada T (2011) Bridging the gap between forest conservation and poverty alleviation: the Ecuadorian Socio Bosque program. Environ Sci Pol 14:531–542

Ferraro PJ, Hanauer MM (2015) Through what mechanisms do protected areas affect environmental and social outcomes? Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 370(1681):267

Garnett ST, Burgess ND, Fa JE, Fernandez-Llamazares A, Moln Z (2018) A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nat Sustain 1(7):369–374

Golden CD, Allison EH, Cheung WW, Dey MM, Halpern BS (2016) Nutrition: fall in fish catch threatens human health. Nature 534:317–320

Katusiime J, Schutt B (2020) Linking land tenure and integrated watershed management—a review. Sustainability 2020(12):1667

Ong PS, Afuang LE, Rosell-Ambal RG (eds) (2002) Philippine biodiversity conservation priorities: a second iteration of the national biodiversity strategy and action plan. Department of Environment and Natural Resources-Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau, Conservation International Philippines, Biodiversity Conservation Program-University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Development Studies, Foundation for the Philippine Environment, Quezon City,

Philippines

Pajaro M, Watts P, Ampa J (2013) The northern Philippine sea: a bioregional development communication strategy. Soc Sci Diliman 9(2):49–72. ISSN 1655-1524 Print / ISSN 2012-0796 Online

Pajaro M, Raquino M, Watts P (2022) Professionalizing community-based coastal resource management (CRM) services. J Ecosyst Sci Eco-Gov 4(Special Issue PAMS16):12–22. PRINT ISSN 2704 4394 | ONLINE ISSN 2782 8522

Pecl GT, Araújo MB, Bell JD, Blanchard J, Bonebrake TC (2017) Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science 355:6322

Sangha KK, Russell-Smith J (2017) Towards an Indigenous ecosystem services valuation framework: a north Australian example. Conserv Soc 15:255–269

Strassburg BN, Iribarrem A, Beyer HL, Cordeiro CL, Crouzeilles R (2020) Global priority areas for ecosystem restoration. Nature 586:724–729

Taheri SM, Hesamian G (2013) A generalization of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and its applications. Stat Papers 54:457–470

Tobón W, Urquiza-Haas T, Koleff P, Schröter M, Ortega-Álvarez R (2017) Restoration planning to guide Aichi targets in a megadiverse country. Conserv Biol 31:1086–1097

UNDRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples) (2013) A manual for National Human Rights Institutions. Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Switzerland

UNU-IAS, Bioversity International, IGES, UNDP (2014) Toolkit for the indicators of resilience in socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS). https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:5435/Toolkit_for_the_Indicators_of_Resilience.pdf

Uprety Y, Asselin H, Bergeron Y, Doyon F, Boucher JF (2012) Contribution of traditional knowledge to ecological restoration: practices and applications. Ecoscience 19:225–237

Watts PD, Pajaro MG (2014) Collaborative Philippine-Canadian action cycles for strategic international coastal ecohealth. Can J Action Res 15:3–21

Watts P, Custer B, Yi ZF, Ontiri E, Pajaro M (2015) A Yin-Yang approach to education policy regarding health and the environment: early-careerists’ image of the future and priority programmes. Nat Res Forum 39(3–4):202–213

Watts PD, Pajaro MG, Raquino M, Anabieza J (2021) Philippine fisherfolk: sustainable community development action research and reflexive education. Local Dev Soc. https://doi.org/10.1080/26883597.2021.1952847

Wehi PM, Lord JM (2017) Importance of including cultural practices in ecological restoration. Conserv Biol 31:1109–1118

Note

The opinions expressed in this chapter are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNU-IAS, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent.

Open Access This chapter is licenced under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ igo/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to UNU-IAS, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. If you remix, transform, or build upon this book or a part thereof, you must distribute your contributions under the same licence as the original. The use of the UNU-IAS name and logo, shall be subject to a separate written licence agreement between UNU-IAS and the user and is not authorised as part of this CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO licence. Note that the link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the licence.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from

the copyright holder.