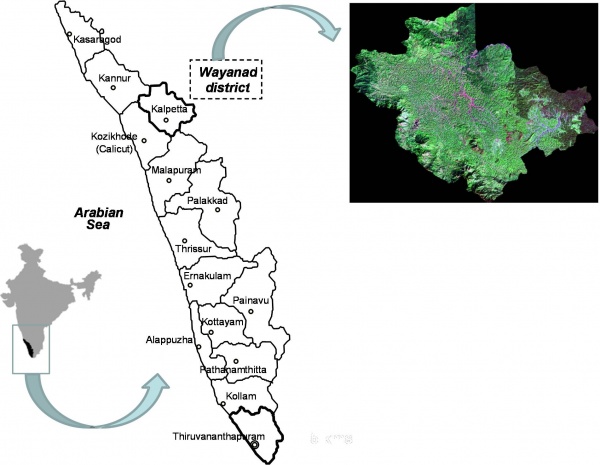

Homegardens: sustainable land use systems in Wayanad, Kerala, India

03.05.2010

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

03/05/2010

-

REGION :

-

Southern Asia

-

COUNTRY :

-

India (Wayanad, Kerala)

-

SUMMARY :

-

A unique region both culturally and ecologically, Wayanad India is populated mainly by homestead farmers utilizing paddy-based cropping systems and homegardens based on local traditional techniques. A typical homegarden represents an operational farm unit which integrates trees with field crops, livestock, poultry and/or fish and has the basic objective of ensuring sustained availability of multiple products for both consumption and sale. Homegardens typically have a high degree of biodiversity as the result of generations of selection by farmers and natures responses to those choices. They are often also the last refuge for species that are useful but not commercially viable for cultivation, and have important social and cultural functions such as the promotion of local trade; strengthening community bonds and saving rural lands from the typical degradations resulting from the alternative of over-intensive agricultural practices. Despite these advantages, homegardens rank quite low in terms of financial bene it as the marketable surplus produced by them is negligible. These lower economic returns in a quickly modernizing society are forcing many farmers to shrink their homegardens, making space available for more remunerative, less environmentally sustainable mono-crops. This shift necessitates a strengthening of the formal and informal institutions attempting to save the farming techniques and traditional land use systems of Wayanad for the sake of both bio-diversity and sustainability.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Agroforestry, Homegarden, Western Ghats

-

AUTHOR:

-

Dr. Santhoshkumar, A.V is an Associate Professor at the College of Forestry, Kerala Agricultural University, India. For a considerable part of his career, he was involved in extension activities related to natural resource management among the farmers of the region. His interests include forest ecology and human – nature interactions shaping landscapes. He has been actively pursuing the developmental issues of wayanad, an ecologically fragile landscape in the state of Kerala. He has also been researching on the impacts of various policies on the nature and natural resources of the region. For his doctoral thesis, he studies the impact of co- management of forests of the region through Joint Forest Management in the state of Kerala. Dr. Kaoru Ichikawa is a consultant at the United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies. She has been working for the programme of the Satoyama Initiative since 2009. Her research interests include structures and changes of landscapes which have developed as a result of human-nature relationships in regions with different natural and socio-economic conditions.

-

LINK: