Conservation for tourism in Kenyan rangelands: a new threat to pastoral community livelihoods

25.08.2016

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Conservation Solutions Afrika

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

25/08/2016

-

REGION :

-

Eastern Africa

-

COUNTRY :

-

Kenya

-

SUMMARY :

-

The “community-owned” wildlife conservancy model was an idea that emerged from the central theme, “benefits beyond boundaries,” of the 2003 International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) World Parks Congress held in Durban, South Africa. This theme implied ensuring the flow of revenues and other nonmonetary benefits of parks to communities whose homes bordered the parks. This came after several years of growing criticism of the “fortress” conservation model that emphasized the fencing and patrol of parks to protect the wildlife confined therein. This new direction presented an apparent departure from the Victorian gamekeeper model that formed the basis of wildlife management structures in Kenya. Generally, this model involved prevention of subsistence use of natural resources by the proletariat in order to ensure their availability for recreational use by the elite. This sharing of benefits was further expanded into a model that proposed the establishment of conservancies outside protected areas, with the aim of creating coherent structures (conservancies) within community-owned lands where communities could formally manage their lands for the conservation of wildlife. This chapter explores how this model and the various interests embedded in it threaten the social and ecological integrity that conserved the wildlife and ecosystems for generations.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Kenya, Conservation, Tourism, Wildlife, Pastoral

-

AUTHOR:

-

Mordecai O. Ogada (Conservation Solutions Afrika)

-

LINK:

-

https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:5769/SEPLS_in_Africa_FINAL_lowres_web.pdf

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Introduction

[Note: this case study originally appeared in the publication “Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes in Africa“.]

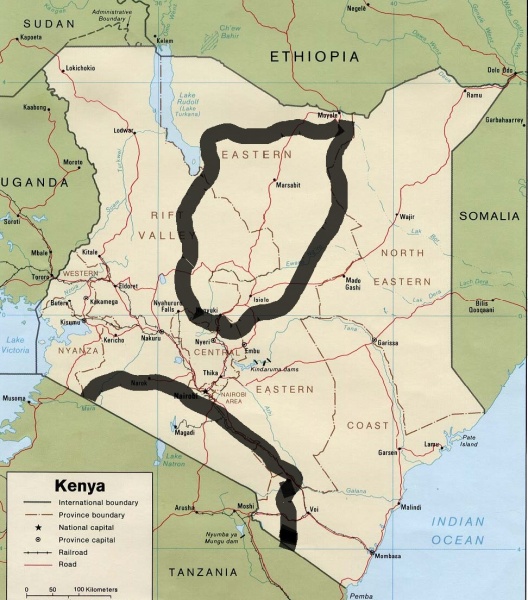

The sites where the majority of these conservancies are located are mainly wildlife habitats in the rangelands of northern and southern Kenya, where the local community are maa-speaking pastoralists (Figure 1). The wildlife species present in the sites include elephant and several carnivore species, including lion (Panthera leo), hyena (Crocuta crocuta), leopard (P. pardus), and African wild dog (Lycaon pictus). The herbivore species include buffalo (Syncerus caffer), impala (Aepyceros melampus), gazelle (Gazella granti, G. thompsoni), zebra (Equus burchelli, E. grevyi), oryx (Oryx beisa), and eland (Taurotragus oryx).

The main benefits obtained by pastoralists from their environment are pasture and water for the livestock. They also obtain wood for fuel and construction of livestock corrals and houses. These resources are shared with the wildlife populations. These lands are community-owned and commonly grazed, so that there are no individual subdivisions of land, given that a key component of pastoralism as a livelihood is unrestricted movement across landscapes. There are no large wildlife populations in nonprotected areas of East Africa, other than the pastoral lands, further underscoring the principle that pastoralism as a livelihood is highly compatible with conservation of wildlife populations. The geographical and temporal niches exploited by the human and wildlife communities in these areas are maintained by the connectivity of habitats and freedom of human, livestock, and wildlife movement between them.

Figure 1: Map of Kenya showing the northern and southern rangelands. Source: Conservation Solutions Afrika

Characteristics of conservancy sites

Northern Kenya rangelands

This zone covers the area from Laikipia county at the southern limit to Marsabit county bordering Ethiopia in the north (Figure 1). The leading exponent of the conservancies model in Kenya is the Northern Rangelands Trust (www.nrt-kenya.org), formed in 2004 in the heady “community conservation” atmosphere that pervaded the conservation sector worldwide immediately following the 2003 World Parks Congress. Adding to the impetus were the efforts of the African Wildlife Foundation [www.awf.org] to develop conservation in the Samburu Heartland. Land is probably the most important component of any terrestrial conservation plan and this new paradigm was based on what was generally described as “nonprotected” areas. This term referred to pastoralist community-owned rangelands that were estimated to contain up to 70% of Kenya’s wildlife populations (Western et al., 1994).

The other important component of this conservation model was the positioning of “enterprise” as the cornerstone of its financial sustainability plan. Crucially, there was never any discussion of the sociopolitical sustainability of this model. The principal component of the conservation enterprise idea is safari tourism, which in East Africa is an industry with a rich history and high potential as a revenue earner. The community ownership of the lands in question coupled with the history and earning potential of safari tourism made the community conservancy model a highly attractive proposition, resulting in its widespread adoption and generous donor support. The geographical areas where these conservancies have been established were functional socioecological production landscapes (SEPLS) and this quality was key to their viability as wildlife habitats. The production system in place (pastoralism) provided a living for the human societies therein, while the necessary mobility of livestock and people under this system maintained viable wildlife habitats, because natural resources were used in an extensive spatial and temporal pattern.

Southern Kenya Rangelands

This area is an approximately 100 km-wide zone along the Kenya–Tanzania border stretching from the Mara plains in the west to the arid Amboseli plains, in the rain shadow of Mt. Kilimanjaro (Figure 1). Nairobi city is situated at the northern limit of the southern rangelands. In southeastern Kenya, the rangelands are more densely populated than those in northern Kenya and the grazing pressure on the pasture is correspondingly greater. There has been a longer-term investment in community-based conservation dating back over 25 years and spearheaded by the African Conservation Centre in the rangelands surrounding the Amboseli National Park. This model preceded the World Parks Congress and differs fundamentally from the Northern Rangelands Trust model in not seeking to impose any particular management regime on the community-owned lands. A major challenge facing conservation in the southeastern rangelands is habitat loss and fragmentation, driven mainly by the urban sprawl from Nairobi. The plains of southwestern Kenya are the northern limit of the Mara–Serengeti ecosystem, which is one of the world’s most productive wildlife habitats and includes the world-famous Maasai Mara National Reserve (MMNR). The productivity of these grasslands also makes the area a prime livestock production zone, occasioning regular incursions of pastoralist livestock into the MMNR and excursions of wildlife into the community lands and resulting in frequent human–wildlife conflicts. The fertile soils and relatively moist climate also support large-scale wheat farming in the area.

Major threats and challenges

Disenfranchisement of Local Communities

A major challenge that the proponents of the conservancy model have failed to meet in Kenya (and much of East Africa) is the inclusion of local communities as intellectual participants in conservation. This failure is a consequence of tourism’s becoming a basis for rather than a byproduct of conservation. The origins of safari tourism in Africa are historically based on the curiosity of people from other continents about the abundant megafauna and landscapes that they encountered when they first came to explore this continent. The people were to be subdued and colonized, a part of this history that has seldom been told and never used in the tourism narrative. Accordingly, the indigenous social fabric of East Africa is still largely excluded from the current conservation discourse.

In general, current conservation practice still presumes that it operates in a vacuum; that is, that there was no thought or philosophy that guided the way in which indigenous African societies lived and interacted with the wild fauna and natural resources around them. One of the results of this thinking is that wildlife research in Africa is designed, implemented, and funded largely by external agents, who advance the paradigm that they have “brought conservation” to the communities among whom they work. Further evidence of this situation lies in the large amount of financial and human resources spent on “awareness creation” about various aspects of conservation. In much of Africa, there has always been and still is a large proportion of resources obtained directly from the environment. These resources include grazing, fuelwood, fish, game, and water. It thus stands to reason that these communities possess some level of knowledge of how to live among and exploit these resources in a sustainable manner (Ogada & Nyingi 2013). In Northern Kenya, the community conservancy model generally entails the demarcation of community land into a unit, which then has a committee with a chairman, secretary, and other office holders. This committee is then given the mandate of managing the conservancy, signing agreements such as leases with investors, and making decisions on resource use. There are also various subcommittees created to manage other issues such as pasture use and security. The “community structures” established by the external agents to manage various processes in the conservancies often ignored the pre-existing community structures, and in reality were found to serve the external agents’ and tourism investors’ interests. Therefore, the designated “core” conservation areas tend to be located in the best and most productive parts of these communally owned lands.

The Dominance of Tourism Interests over Conservation Needs

The tourism industry has continued to exert a strong influence over conservation practice in Kenya, as the “primary users” of wildlife populations. This influence has grown to a point where the tourism industry has grown from being a beneficiary of conservation into the basis thereof. The expected earnings from foreign tourists have been put forward by NGOs as a reason for communities to conserve their wildlife, despite all the unpredictable variables associated with this particular livelihood option to woo tourism investors to the new conservancies, conservation NGOs invested in drawing up leases that heavily favored them at the expense of communities. The communities were convinced with promises of large profits and other benefits from conservation. The first shortcoming of this arrangement is the model that gives communities a share of the profits, rather than a fixed lease fee or rent from these tourism facilities. Once the investors are brought in, the community’s gain from the business is entirely dependent on the profits declared by the investor, a variable that is easily manipulated, to the detriment of the communities.

The second shortcoming is the misconception spread amongst the communities that makes them observe and perceive donor-funded projects and developments as “benefits of conservation.” An example in the southern Kenya rangelands is the Shompole conservancy, approximately 160 km south of Nairobi. It was set up in the year 2000 by the local community with the assistance of the African Conservation Centre [www.accafrica.org] with the key objective of resisting the progress of subdivision and consequent loss of pasture and wildlife habitat. This aim draws from a widely held consensus that the survival of wildlife populations and pastoralism as a livelihood depends on the maintenance of open grasslands (Curtin and Western 2008). Following the establishment of the conservancy, governance structures were set up and the success of this model resulted in the conservancy’s winning the Whitley award in 2003. The progress of this conservancy continued with the construction of the Shompole luxury eco-lodge at a cost of over $5 million. As a result of aggressive marketing, this lodge rapidly became a model for community-based tourism enterprises. Again, a key misconception in this discourse is people’s failure to realize that use of the term “community-owned” facility does not necessarily mean that the community in question are the decision-makers in the management of the facility. The majority of such facilities are leased to external investors who are believed to have the requisite marketing skills and connections to the client source markets. Therefore, decisions such as the exclusion of livestock grazing, fetching water, firewood collection, and other resource uses from the “tourism area” around the lodge are spuriously attributed to the community members. This misconception masks the need for conflict-resolution mechanisms, which are often absent from these lease agreements. There are three fundamental threats to these tourism operations in community-owned lands.

- The fickle nature of the tourism industry, which is easily affected by several extraneous factors such as global insecurity, economic downturns, or disease outbreaks (such as Ebola) that reduce profits and community benefits.

- The lack of local capacity, excluding locals from the skilled jobs in a facility of which they are the “owners.”

- Community eco-lodges are typically small facilities whose profits cannot provide for an entire community, even at 100% occupancy. Shompole lodge, for instance, had a total of six rooms and two suites. The majority who are not participants in the tourism venture only suffer loss of pasture.

In 2012, less than 10 years after the lodge was built and after hundreds of thousands of dollars of investment in development of the conservancy, there was serious discontent in the conservancy over perceived inequitable sharing of benefits, and it came to a head in 2014 when the lodge was burned down by members of the community after the investors were ejected. The culprits were arrested, but the process of prosecuting the crime has divided the community between those who were perceived as beneficiaries of the project and the rest of the community. An important point to note is that it was impossible for the facility to provide substantial income for the community, and that the entire concept was fundamentally flawed.

Photo 1: Shompole lodge before it was burned down. Photo credit: African Horizons 2013.

In a separate case, there was an invasion of the Nguruman Kamorora ranch in October 2014 by local herders in which the lessee, Mr. Hermanus Steyn, and his employees were violently evicted and property, including a luxury tourist facility and vehicles, were burned. The land was “taken” from the Maasai community by Mr. Steyn in 1986 according to Mr. John ole Nairowua, a local leader, on the pretext of setting up a tourist lodge and a game sanctuary in 1986 and “the owners of the land do not benefit from it.” The spread of this anti- “investor” sentiment indicates shortcomings in the community conservancy model as currently practiced and calls for a re-evaluation. It is likely to be a more serious problem in the rangelands of northern Kenya, where the proliferation of small arms is an additional threat to security. However, the current model is currently expanding rapidly, driven by heavy grant inflows from various donors, including foreign governments.

Photo 2: An armed Maasai moran guarding a burned tourist cottage at Nguruman conservancy in 2014. Photo credit: Daily Nation newspaper, November 9 2014.

Disintegration of pastoralism as a livelihood

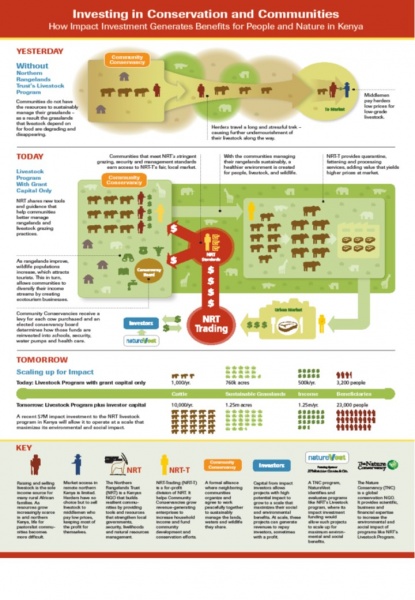

Pastoralism existed in the Kenyan rangelands for several centuries before the introduction of structured conservation. The presence of large wildlife populations in the rangelands is testimony to the compatibility of this particular land use with wildlife conservation, forming vast socioecological production landscapes. However, tourism investments market a “wilderness” product that does not include pastoralists and their livestock, and conservation interests have sought several ways of separating livestock and conservation areas. A case in point is the “management of grazing”; traditionally, this is the remit of the morans (warrior age group) in pastoralist societies. This tradition reflects the reality that livestock are the most valuable resource (economically and culturally) and that grazing the animals is combined with the function of security. A study by Hawkins (2015) in a cluster of six NRT conservancies found that the morans were often described by conservancy managers as “disobedient” and “uncooperative” with reference to the objectives of the conservancy. Another key finding was that 62% of the morans interviewed had never heard of the “planned grazing” stipulated by the conservancy management. This exclusion was found to preclude the support of this vital demographic group for conservation objectives, leaving coercion as the next viable option. One of the tools for application of this pressure is the NRT Livestock to Markets Program, a scheme ostensibly conceived to strengthen the livestock production value chain (Figure 2). Cattle purchased from pastoralists under this scheme are quarantined on Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and fattened and slaughtered on Ol Pejeta (a collaborating commercial cattle ranch), with profits covering NRT Trading’s costs and contributing a levy to cover some of the conservancy management costs. This market aims to incentivize conservancies to practice effective, transparent governance, and sustainable natural resource management by linking local livestock owners in high-performing conservancies with ready markets (NRT 2014). The strict stipulations detailed in the schematic diagram raise questions over whether the scheme is designed to economically empower the communities or impose certain regulations on them, cases in point being that

- Cattle are purchased only from those deemed to adhere to the strict (NRT-imposed) grazing, security, and management rules.

- Cattle are purchased at “fair” price as determined by the purchaser. The producer has no further participation after this point.

- Cattle are quarantined, fattened, slaughtered, and sold by NRT

- Profits from the value addition in (c) go to NRT Trading.

- The only other gain for the community is from expected improvement in rangeland condition (from de-stocking) that is expected to increase wildlife populations, which in turn is expected to increase tourism revenues, with this increase expected to trickle down to them.

Figure 2: NRT Livestock to Market program schematic. Source: Northern Rangelands Trust

Apart from the profits accruing to NRT Trading and the returns to the investor, the only other net effect is the de-stocking of the landscape. Even the levy imposed on every purchased cow is passed on to the group ranch committee, which decides on its expenditure. In the schematic diagram, the initial objective is to improve on a situation where grasslands are in poor condition, ostensibly due to overstocking, and pastoralists are receiving low prices from middlemen for low-quality livestock. The new system is seeking to improve the rangelands by reducing the numbers of livestock and is replacing the middleman with a grant-funded trading company, with this replacement also skewing the local livestock market against private enterprise. Pastoralism is an activity that covers extensive geographical areas, so that the market distortion from this scheme would be expected to spread beyond its target area. Without appropriate checks and balances, this system can lead to massive disempowerment of livestock producers. This weakening of pastoralist livelihoods can also damage Kenya’s national economy. Over 70% of Kenya can be classified as arid or semiarid, and livestock production is the cornerstone of these vast SEPLs. Western & Finch (1986) showed that indigenous East African cattle display energy-sparing capabilities during drought. Pastoralists can thus herd cattle at great distances from water at little more cost than animals on the normal maintenance diet and watered more frequently. The physiological response of cattle to drought, the ecological constraints imposed by livestock and wildlife competition, and the energetic efficiency of mixed milk and meat pastoralism explain why herders traditionally select their characteristic management practices (Manzolillo Western & Nightengale 2006). When these practices are restricted, replaced, or otherwise compromised, the equilibrium of the entire system is at risk.

This model poses an existential threat to pastoralism as a livelihood, exacerbated by high land prices that drive a vicious cycle whereby land is sold and the earnings are invested in even more livestock. In the last two decades, tourism has been touted in Kenya as the basis for conservation, the panacea for human– wildlife conflict, and the ultimate environmentally sustainable livelihood option in non-protected wildlife habitats.

Conclusion

The prevailing thinking that currently informs the implementation of conservation projects in Kenya has its origins in the laws and regulations that are in place to manage wildlife (enforced by the Kenya Wildlife Service). These, in turn, originated from the practice of gamekeeping in Victorian England, which was brought to Kenya by the British colonizers of the time. This paradigm is largely responsible for the difficulties currently faced in the effective and sustainable management of wildlife and other natural resources in Kenya. It presumes that there was no culture, thought, or philosophy that guided the way in which precolonial African societies lived and interacted with the wild fauna around them. One of the results of this thinking is that wildlife research and conservation practice in Kenya is largely designed, implemented and funded by external agents, who are widely believed to have “brought conservation” to the communities with which they work. In Kenya and much of Africa, there has always been a large proportion of resources obtained directly from the environment. These include grazing, fuelwood, fish, game, and water. It thus stands to reason that these communities possess some level of knowledge of how to live among and exploit these resources in a sustainable manner. This, in essence, is the way in which socioecological production landscapes in Kenya’s rangelands have functioned for centuries. It is important that movements like the International Partnership for Satoyama Initiative (IPSI) identify the reasons for the dominance of tourism interests in the conservation sector in Africa, and reintroduce support for the existing livelihoods that have maintained these ecosystems for centuries.

The creation of social, mechanical, and economic barriers to the free movement that has maintained the biodiversity in these socioecological production landscapes is a serious threat to their existence and the diversity they support. The disruption of human societies that have learned to coexist with wildlife will ultimately damage the natural and human environment, an effect that will be felt far beyond the landscapes in question. It is therefore imperative that technical expertise is applied toward adjusting this balance to new realities, rather than creating a false “reality” that is socially, economically, and environmentally unsustainable.

References

Curtin C & Western, D 2008. Grasslands, People, and Conservation: Over-the-Horizon Learning Exchanges between African and American Pastoralists. Conservation Biology

Hawkins B. 2015. Take Me to Your Male Elder: Institutional Marginalization of Pastoral Warriors in northern Kenya Land Management. MSc. Thesis, Human Dimensions of Natural Resources Department, Colorado State University

Kantai P Katere F & Serumaga, K 2012. How Politicians gave away $ 100bn of Land. The Africa Report No. 42, 2012. Novafrica Developments.

Manzolillo P Nightengale DL and Western D 2006. The Future of the Open Rangelands: An exchange of ideas between East Africa and the American Southwest. African Conservation Centre and African Centre for Technology Studies, Nairobi, Kenya.

Northern Rangelands Trust 2014. State of the Conservancies Report.

Ogada, MO & Nyingi, DW 2013. The Management of Wildlife and Fisheries Resources in Kenya: Origins, Present Challenges and Future Perspectives. In: Paolo Paron, Daniel Olago & Christian Thine Omuto, (eds) Developments in Earth Surface Processes, Vol. 16. Elsevier Amsterdam: The Netherlands.

Western D & Finch V 1986. Cattle and Pastoralism: Survival and Production in Arid Lands. Human Ecology Vol. 14.