The socio-ecological production landscapes of three ethnolinguistic enclaves in the Dagestan high Caucasus. Sustaining a multi-millennial agro-pastoral continuum - the example of Verkhnee Gakvari.

10.12.2021

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION

Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development, Dagestan State University, Makhachkala, Russia

DATE OF SUBMISSION

23/11/2021

REGION

Europe

COUNTRY

Russia

LOCATION

Tsumadinskiy District, Republic of Dagestan

KEYWORDS

high mountain communities, sustainable agro-pastoral economy, ecological altitudinal zones, cultural landscapes, ethno-linguistic enclaves, ecology and education.

AUTHOR(S)

– Guy Petherbridge, Professor, Caspian Centre for Nature Conservation, Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development, Dagestan State University, Mahachkala, Republic of Dagestan, Russia

– Magomed M. Ismailov, Director, Verkhnee Gakvari School, Verkhnee Gakvari, Tsumadinskiy District, Republic of Dagestan, Russia

– Shamil M. Ismailov, Teacher, Verkhnee Gakvari School, Verkhnee Gakvari, Tsumadinskiy District, Republic of Dagestan, Russia

– Murtazali Kh. Rabadanov, Rector, Dagestan State University, Makhachkala, Republic of Dagestan, Russia

– Alimurad A. Gadzhiev, Director, Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development, Dagestan State University, Mahachkala, Republic of Dagestan, Russia

– Abdulgamid A. Teymurov, Deputy Director, Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development, Dagestan State University, Mahachkala, Republic of Dagestan, Russia

– Saipov D. Magomedkhabibovich, Member, Committee of Agrarian Affairs, Nature Management, Ecology and Environmental Protection, Peoples Assembly of the Republic of Dagestan

– Murtazali R. Rabadanov, Adviser to Rector, Dagestan State University, Makhachkala, Republic of Dagestan, Russia

– Madina G. Daudova, Editor, South of Russia, Ecology, Development, Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development, Dagestan State University, Mahachkala, Republic of Dagestan, Russia

– Abdul-Gamid M. Abdulaev, student researcher, Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development, Dagestan State University, Mahachkala, Republic of Dagestan, Russia

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

“If a person has enough bread at home, he is not in need of a foreign language and a foreign soil.” Dagestan mountain proverb

Location and General Geographical Characteristics of the Andiiskoe Koisu

In this case study report we describe the distinctive high-altitude socio-ecological production landscapes of the Bagulal, Chamalal and Godoberi ethnolinguistic enclaves in the valley of one of Dagestan’s most important river arteries and examine factors that have contributed to both their formation and continuing function as balanced geoecosystems for thousands of years after they were first permanently inhabited by man. Particular attention has been paid in the course of undertaking this case study to understanding the contribution which social mores, religious beliefs and state public education have made to communal environmental management in the Chamalal community of Verkhnee Gakvari, which findings have been recently published [3]

The outstanding feature of the massive complex of mountains, piedmonts, rivers and valleys known as the Caucasus is the Main Caucasus Range or Greater Caucasus which extends east-southeast to west-northwest for some 1,200 km from the Absheron Peninsula on the Caspian Sea to the Taman Peninsula between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.

The northern macroslopes and outlier ranges of the Greater Caucasus are the watershed for a number of rivers whose valleys slice through the extensive highlands of Dagestan to reach the Caspian Sea. The most northerly of these is the Andiiskoe Koisu (River) whose source is in the Republic of Georgia just south of its border with the Russian Federation. For some 60 km from the border the Andiiskoe Koisu has cut a deep valley in a north easterly direction between the Snegovoy Ridge to the west and the Bogossky Ridge to the east (both have summits over 4,000 m) until it turns to the east below the town of Botlikh [1]. (Fig. 1)

Today, driving upstream along the Andiiskoe Koisu from its convergence with the Avarskoe Koisu to form the Sulak River, one passes along a broad valley bordered by lofty barren mountain escarpments with patches of conifers on the heights. These dry central and lower reaches of the Koisu are in a rain shadow. Along and above its banks, riverine communities have used terraces provided by nature and constructed artificial stone walled terraces to support dense orchards of fruit trees (primarily apricots – the main commercial crop of the region- but also plums, peaches, nectarines and cherries). The soil between the trees is used to grow corn and a range of vegetables (pumpkins, pulses, tomatoes, onions, peppers, aubergines, leafy greens, etc.).

Figure1. Topographical map showing location of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu and its valley (large black box) and of Godoberi, Chamalal and Bagulal community territories (small black box). Soviet military map 1:500,000, 1942 (Grozny – sector K-38-Б). The inset shows the location of the Tsumadinskiy District in the Republic of Dagestan. The Godoberi territories are in the adjacent Botlikhskiy District to the north.

Topography and Early Human Settlement of the Northern Sector of the Upper Andisskoe Koisu Valley

However, on approaching the gorge which defines the entry to the territory of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu, the vertical configuration of the cultural landscape abruptly reverses, as it were, from that downstream. This is first noticeable in the elevated placement of the sister settlements of Nizhnee (Lower) and Verkhnee (Upper) Godoberi (Botlikhskiy district) which dominate the landscape of the northern face of the Zhaloo Ridge. They are situated high above the river in the midst of extensive croplands backed by dense pine forests. Below and to the east, steep barren terrain slopes down to the Koisu, the whole creating a distinctively different cultural landscape from that prevailing in its central and lower reaches where agriculture is conducted primarily in the lower zone adjacent to the river and the settlements along its banks [2]. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2. Panoramic view south from Botlikh of the Godoberi territories of Nizhnee Godoberi and Verkhnee Godoberi on the Zhaloo Ridge situated in the midst of croplands with forests above and mountain pastures at a higher elevation on the right. The gorge on the left is the entry to the upper Andisskoe Koisu.

Figure 3. View of the other side of the ridge shown in Fig. 2, where the gorge of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu slices through the great ramparts of the Niguli Meidan and the Zhaloo Ridge (in the background). The croplands of Bagulal Gimerso are in the foreground with Kvanada behind. Across the Koisu can be seen the sloping lands of Chamalal Gigatli. Photo: Alexandr Krull [http://id8008405.35photo.ru/photo_426142]

The distinctive high-altitude cultural landscapes of the Godoberis and their neighbours, the Chamalals and Bagulals, (Fig. 3) are the result of a unique continuum of human settled occupation for some six millennia or more (possibly as long as eight millennia), which modern advances in archaeological sciences, linguistics and population genetics are now helping us to understand in the process of a research and socio-ecological sustainability project in the region being undertaken by the Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development of Dagestan State University in collaboration with local communities, the administration of the Tsumadinskiy District (which encompasses most of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu region) and relevant government agencies. This project is being undertaken within the framework of the concepts of the International Partnership of the Satoyama Initiative and is entitled “Conserving the Mountain Fastness of the Upper Andiiskoe Koisu: A Unique Multi-Millennial Cultural Continuum”. Its first major undertaking has been research carried out in the course of this IPISI SEPL case study, resulting in a separate publication, “Verkhnee Gakvari: the contribution of adat, religious beliefs and public education to collective environmental management in an agro-pastoral community in the Dagestan high Caucasus.” [3] The present article is a report referring to the basic findings of this research in the context of a broader survey of the regional typology of socio-ecological production landscapes specific to the northern sector of the upper basin of the Koisu, including that of Verkhnee Gakvari.

The geomorphology of the natural landscape and climate of this north-central area of the Andiiskoe Koisu valley determined the placement, process and character of human settlement. Its landforms and ecology must be understood in the context of the Last Glacial Period (c.110,000 – 11,000 years ago) and the warming of the deglaciation period in its aftermath [4] . Although humans may have existed in this geographical zone previously, given that just two hundred km to the south in Dmanisi in Georgia, the remains of the first hominids recorded in Europe have been excavated (dated to c. 1.8 million years ago), any traces have been obliterated as consequence of the extensive glaciation of the mountainous Caucasus during the Last Glacial Period. Remnants of this glacial phase still survive as the modern glaciers of the Caucasus, the greatest concentration of which in Dagestan lie among the highest summits of the Bogossky Ridge which constitutes the eastern flank of the Andiiskoe Koisu valley [5].

As the areas under ice gradually retreated following the Last Glacial Period, certain characteristic landforms resulting from glacial or periglacial erosion were revealed in the upper altitudes of the highlands east and west of the course of the Koisu. These were further modified by the heightened fluvial erosion and alluvial deposits associated with the ice melt. Vegetation began to re-clothe the region and humans returned to hunt and forage. As the climate developed in successive phases – widely varying in patterns of temperature and humidity – to a regime similar to that of today, the rich biodiversity of flora and fauna which now characterize the region became established [6]. Mesolithic practices of using the natural environment were eventually supplanted by agro-pastoral practices of sedentary communities characteristic of the Neolithic period, genetic studies pointing to these populations as originally having a Near Eastern origin [12].

Geoecology and Agro-pastoralism of the Godoberi, Chamalal and Bagulal Ethnolinguistic Enclaves

Geomorphic processes of periglacial and fluvial action left areas of deep soils in the northern sector of the highlands flanking the upper Andiiskoe Koisu and its tributary valleys which could be levelled by plough and hoe into terraced arable fields with boundary slopes of high stability which did not need the stone retaining walls developed in dryer areas of sparser soil elsewhere in highland Dagestan.

The climate in this section of the Andiiskoe Koisu valley was conducive to both agriculture and human settlement [7] with the added benefit that it did not host the mosquitos which transmitted chronic malaria in the coastal lowlands and lower river valleys [8]. The insect pests of lowland farming also did not ravage crops at these upper elevations. Some cereals grow well at the altitude of these settlements and were the basis of sedentary subsistence agriculture, the grains sown (spelt, wheat, barley, rye and oats – including species endemic to the Transcaucasus and Caucasus) being adapted to local conditions through the long passage of time by both human and natural selection [9]. The small-statured cattle and the sheep varieties introduced during the early phases of human settlement also adapted to local natural fodder, steep landscapes and climate [10]. The introduction of donkeys, first domesticated in north-east Africa and used in the Northern Levant and Mesopotamia since the later fourth millennium BC, was a major factor in the consolidation of settlement, providing a hardy and easily manageable means of human and utilitarian transport in this mountainous terrain [11]. Villages with flat roofed buildings of stone, earth and timber construction were built in strategic locations which facilitated their defense.

Thus these early settlers had found and were to optimize bio-niches ideal for their needs. In each of the tributary valleys (or adjacent valleys in some cases) of the Koisu small distinct ethnolinguistic groups were established, developing individual languages which differed from those of their neighbours. Archaeological, linguistic and genetic research findings complement one another to indicate that there were no further substantial migrations into these inner recesses of the Dagestan highlands. Karafet et al note that cultural continuity of these sedentary communities with the earlier Mesolithic strata suggests that plant and animal domestication spread to this region by diffusion rather than by population replacement [12]. The results of this study are critical for understanding the foundations of the millennia-long in situ continuum of the ethnolinquistic enclaves neighbouring one another along the upper reaches of the Andiiskoe Koisu. The findings are reinforced by recent analyses of carbon and nitrogen stable isotope compositions of human and animal collagens from Early Bronze Age contexts in the North Caucasus by Knipper et al which suggest that during all time periods the home range of human communities in the mountains remained generally limited to movements within their respective landscapes. Only a few animal or human individuals revealed stable isotope data that point to a possible origin in a landscape other than that where their skeletal remains were found [13].

In this case study we focus on the Godoberis, Chamalals and Bagulals ethnolinguistic groups who use their territorial landscapes in similar ways (Fig.4) Their languages belong to the Andian subgroup of the Avar-Ando-Tsez (Avar-Ando-Dido) group of the Nakh-Dagestan branch of the Northeast Caucasian family of languages [14]. These communities all practiced patrilocal endogamy and did not intermarry with neighbouring ethnolinguistic groups, each thus perpetuating a genetically homogeneous gene pool, although they shared the same agro-pastoral systems [15]. It appears from genetic research that language and genetic variation in the high Dagestan Caucasus evolved together as farming was adopted by pre-existing Mesolithic populations in the region. Genetic research points to Dagestan highland populations having a common origin in the Near East and that the Proto–Nakh–Dagestanian from which these languages evolved appears to have developed in the piedmonts and highlands of the eastern Caucasus as agriculture initially spread there from the Near East [16].

Figure 4. Relief map showing highland settlements on both flanks of the Andiiskoe Koisu referred to in text. Right flank – Bagulal territory: Khvanada (Кванада), Gimerso (Гимерсо), Tlondoda (Тлондода) and Khushtada (Хуштада). Left flank – Godoberi territory: Nizhnee Godoberi (Нижнее Годобери) and Verkhnee Godoberi (Верхнее Годобери). Chamalal territory: Gigatli (Гигатль), Gadiri (Гадири), Nizhnee Gakvari (Нижнее Гаквари), Verkhnee Gakvari (Верхнее Гаквари), Gigikh (Гигих) and Richaganikh (Ричаганих). At the riverine level are the Chamalal communities of Gigatli Uruk (Гигатль Урук), Agvali (Агвали) and Kochali (Кочали). The inset shows areas of glaciation and periglaciation of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu during the Last Glacial Period [16]).

These ‘endemic’ local languages of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu basin are all non-written and are classified by UNESCO as endangered (Avar and Russian having serving the region as the lingua franca in both oral and written communication since Tsarist occupation in the second half of the 19th century to the present) [17].

The territory of each of the main highland settlements of these enclaves occupies a distinctive post glacial mountain geoecosystem. Along both flanks of the north central Andiiskoe Koisu is a series of tributary river valleys separated by high ridges. On the Bagulal right flank of the Koisu, the north face of each of these ridges appears to have been shaped by periglacial action during the Last Glacial Period and later further eroded by the powerful forces of fluvial erosion to leaving landforms with what are technically termed as “complex concave convex mountain slopes” shaped somewhat like an amphitheatre in which lie deep arable soil deposits [18]. These formations are clearly understood by reference to the contouring in detailed topographic maps of these areas. (Figs. 4 & 8) The geomorphologies of the Godoberi and Chamalal community territories are also the product of successive processes of periglacial and subsequent post glacial fluvial erosion and alluvial deposition (see below).

Godoberi Territory

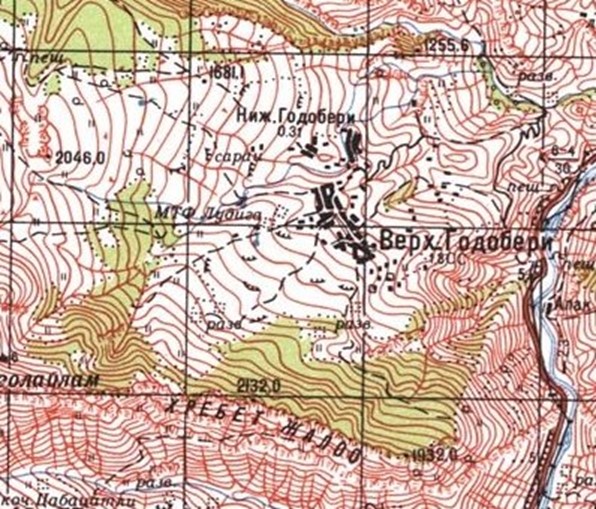

As observed above, the Godoberi ethnolinguistic group’s two main villages, Nizhnee (Lower) Godoberi and Verkhnee (Upper) Godoberi [19], lie in the midst of a broad territory of glacial, periglacial and fluvial erosional morphology on the north face of the Zhaloo Ridge. Its rich soils have been shaped into multiple layers of terracing with grass-covered boundary slopes [20]. (Figs. 2 & 5)

Figure 5. Topographical map with contours showing relief configuration of the territory of Nizhnee Godoberi and Verkhnee Godoberi, including the forested areas backing the croplands. Soviet military map 1:100,000, 1984 (Botlikh sector k-38-57).

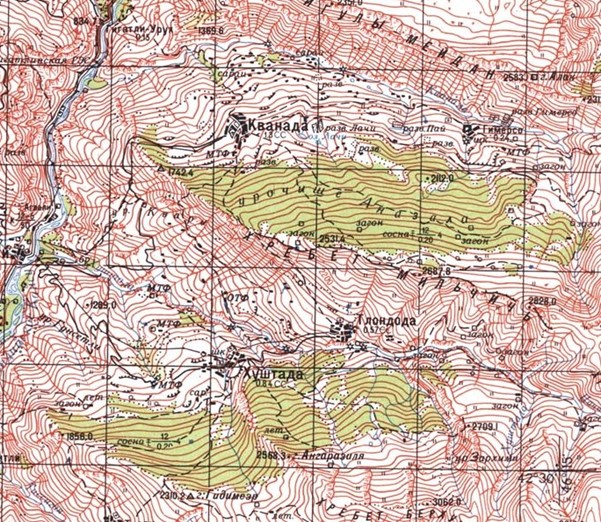

Bagulal Territory

The main settlements of the Bagulal ethnolinguistic group [21] are Kvanada, Gimerso, Tlondoda and Khushtada (Figs. 4 & 8) on the right flank of the Andiiskoe Koisu. The Niguli Meidan defines the Bagulals’ northern boundary, dominating the settlements of Kvanada and Gimerso which are separated from it by a deep gorge. (Figs. 3 & 5-7). The north-facing pine forested ridge behind them flanks the valley of the Khushtadarinka River to the south. The territory of Khushtada has topographical similarities to that of Kvanada territory. (Figs. 9-11) The territory of Tlondoda is opposite and separated from it by the Khushtadarinka gorge. (Fig. 10)

Figure 6. View from the west of the Bagulal settlement of Khvanada and its distinctive land form. Below flows the Andiiskoe Koisu.

Figure 7. The settlement of Khvanada in early winter after the crops have been harvested.

Figure 8. Topographical map of the Bagulal lands in the Tsumadinskiy District showing Khushtada, Tlondoda, Kvanada and Gimerso territories including the forested areas adjacent to their croplands. Soviet military map 1:100,000, 1984 (Botlikh sector k-38-57).

Figure 9. View of the Bagulal territory of Khushtada from the west.

Figure 10. Winter view from croplands below the village of Khushtada towards the ruins of the old village (centre) and the territory of Tlondoda on the opposite side of the Khushtadarinka River.

Figure 11. The dense pine forest above the Khushtada settlement. Agvali can be seen below on the bank of the Andiiskoe Koisu. The Zhaloo Ridge escarpment is the border between the Godoberis and Chamalals.

Chamalal Territory

On the opposite (left) flank of the Koisu, the main highland settlements of the Chamalals [22] from north to south are Gigatli, Gadiri, Nizhnee Gakvari, Verkhnee Gakvari and Richaganikh. Another great escarpment wall, that of the south face of the Zhaloo Ridge, defines the Chamalals’ northern boundary with the Godoberis. At the riverine level lie the Chamalal settlements of Gigatli-Uruk, Agvali (now the Tsumadinskiy District administrative centre), Kochali and Tsumada Uruk. (Figs. 12-15)

Figure 12. View westwards from below the settlement of Khushtada encompassing the Chamalal territories of Gigikh, Kochali, Agvali, Gadiri and Gigatli.

Figure 13. View westwards to the territory of Gadiri situated high above the Gadirinka River on the left

The territories of the Gigatli (Fig. 14) and Gadiri and Richaganikh communities occupy landforms of similar general typology to those of the Bagulals, although on a lesser scale. Nizhnee Gakvari and Verkhnee Gakvari are situated in a long valley of different geomorphology which has undergone a process of considerable fluvial erosion. (Fig.18)

Figure 14. Topographical map of the Chamalal territories on the left flank of the Andiiskoe Koisu valley. Soviet military map 1:50,000,1984 (Botlikh sector k-38-57).

Figure.15. View from pastures above Gidatli to the village and the Zhaloo Ridge.

Bagulals and Godoberis is that of a now abandoned Chamalal settlement of Verkhnee Gigikh, situated at a height of about 2,000 m asl with its small sister community, Gigikh, below situated in its tributary valley adjacent to Agvali. The fields and now roofless buildings (including a mosque) of Verkhnee Gigikh are still witness to a once prosperous community. Its small group of abandoned structures overlooking the vast landscape of the Koisu and the snowy peaks of the Bogossky Ridge are situated on the edge of an expanse of level croplands, backed by a sloping ridge of coniferous forest. (Figs.15 & 16).

Figure 16. View eastwards of the forest, fields and abandoned village of Verkhnee Gigikh with its distinctive landform. Note the settlement of Gigikh below to the left located nearer the level of the Andiiskoe Koisu.

Figure 17. The village of Gigikh. An example of the deep soils supporting agriculture in these high-altitude communities.

Figure 18. View eastwards from the Snegovoy Ridge over the territories of Verkhnee Gakvari and Nizhnee Gakvari across the Andiiskoe Koisu to the peaks of the Bogossky Ridge. Note forests on the

right flank of the Gakvarinka River near the upper village.

Eco-functional Altitudinal Zonation of Godoberi, Chamalal and Bagulal Communities

The principal highland settlements of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu valley are all situated at the upper levels of sustainable human comfort in terms of temperature and year-round accessibility within a boundary zone between what are generally accepted as subalpine and alpine altitudes at these latitudes, that is between approximately 1,600 and 2,200 m asl.

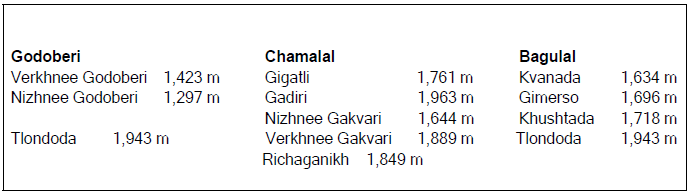

The elevations of the principal highland settlements of the three ethnolinguistic groups discussed here are provided below (Fig. 19).

Figure 19. Elevations of principal highland settlements of the Godoberis, Chamalals and Bagulals.

Apart from the macro geomorphological aspects of the territorial landforms of the Godoberi, Chamalal and Bagulal communities described above, our research has revealed a common pattern of successful harnessing of ecology and function according to the altitudinal zonation of each community’s territory within its tributary river valley.

Figure 20. The village of Verkhnee Gakvari in early summer.

Figure 21. Village of Verkhnee Gakvari in early autumn in the midst of its croplands after the harvests and haymaking.

In community territories of the sector of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu discussed here, horizontal eco-functional altitudinal zonation is relative to the vertical axis of the tributary river which is a defining geomorphological feature of each community, each river taking the name of the community through whose territory it flows, e.g. the Gakvarinka River, the Gadirinka River, the Khushtadarinka River, etc.

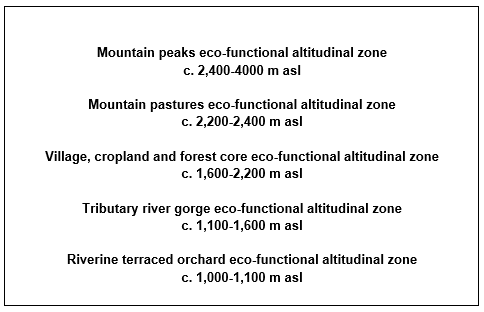

In this schematic analysis the elements of this eco-functional zonation according to altitude are as follows (Fig. 22, see also conceptual diagram in Petherbridge et al 2021, Fig. 7, p. 147) [23].

Figure 22. Generalised schematic of eco-functional zones according to altitude of the high mountain communities on either flank of the norther upper reaches of the Andiiskoe Koisu.

Village, cropland and forest core eco-functional altitudinal zone (c. 1,600-2,200 m asl)

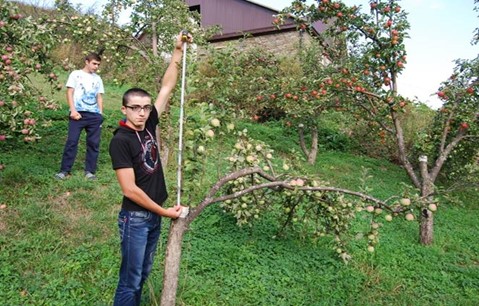

Schematically, the core altitudinal function of each community is that of the village itself, where most members of the community live and where its Juma mosque is located. Here we illustrate the various functions using the example of Verkhnee Gakvari. The main settlement is usually located in a central location allowing efficient access to the community’s fields where subsistence staples and summer vegetables (pumpkins, carrots, pulses, onions and garlic) arere grown on the best soils. (Figs. 23-26) Apples also produce well at temperatures at this elevation. (Fig. 43) Here produce and hay was stored and animals housed in family outbuildings. Here in the past the village blacksmith had his workshop producing agricultural instruments and items needed in building, etc. Natural springs and the community’s eponymous river or rivulets which flowed into it provides water for all its purposes, including religious ablutions at the mosque. Some of the springs are particularly valued for health and medicinal purposes.

Figure 23. A pair of the local small mountain cattle pulling a plough in a field adjacent to the village of Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 24. Tending young potato plants in a field near the village, Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 26. Harvesting carrots near the village. Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 25. Havesting potatoes in a field near the village. Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 27. Cutting hay above the croplands. Verkhnee Gakvari.

On the upper periphery of the area where staple crops were cultivated, as well as on fallowed fields, wild grasses grow, providing hay which is harvested in late summer or early autumn for winter fodder. (Figs. 27-29)

An important eco-functional component of these community territories was that of a forest adjacent to, and in most cases higher, than the settlement and its croplands. In all but one case (Verkhnee Gakvari), in the region of the Andiiskoe Koisu being described here the forest is primarily of the conifer, Pinus sosnowskyi Nakai, which is specific to this part of the Dagestan Caucasus (the native forest adjacent to Verkhnee Gakvari is of deciduous species, primarily birch) [24]. These community forests provided a convenient source of fuel and timber for building construction and the manufacture of domestic and agricultural implements, furniture, food storage structures (ambar) [25] (Fig. 30), etc. It also supplied edible funghi, wild berries and fruits, as well as a range of plants used in traditional medicine [26]. Indeed, each of the altitudinal zones below that of the alpine mountain peaks is the habitat of specific plants, berries or fruits gathered either as medicines and food. Nowadays forest wood is less and less used for traditional purposes. Domestic fuel for heating, lighting and cooking is now provided by gas and electricity recently connected to most of the mountain villages of the Tsumadinskiy and Botlikhskiy Districts.

Figure 28. Gathering hay to be taken by donkey and stored as winter fodder. Verkhnee Gakvari

Figure 29. Donkeys equipped with wooden saddles for transporting hay. Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 30. Wooden domestic storage ambar. Gadiri.

Mountain pastures eco-functional altitudinal zone (c. 2,200-2,400 m asl)

In most community territories, at altitudes higher than the villages and central croplands there is a zone of natural grasslands and meadows which provided excellent and convenient pasturage for sheep, goats and cattle. (Figs. 31-34)

Figure 31. A watering place for sheep, goats and cattle in pasture zone above the village. Verkhnee Gakvari

Figure 32.Evening milking in traditional cow byre.

Figure 33. Cooperative building of a corral in the pasture zone above the village. Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 34. Fat-tailed Dagestan mountain sheep grazing on the slopes below the settlement of Khushtada. Zhdoo Ridge in background.

Mountain peaks eco-functional altitudinal zone (c. 2,400-4000 m asl)

Higher still is the true alpine zone of wilderness peaks and ravines above the tree line, the habit of game animals such as the East Dagestan tur and the bezoar goat, once hunted by local inhabitants but now almost exclusively by state-regulated trophy hunters. (Figs. 34-35)

Figure 35. Winter view of Tlondoda (note minaret in upper left) westwards to the Snegovoy Ridge. The long snowy valley is that of the Gakvarinka River and the territories of Verkhnee Gakvari and Nizhnee Gakvari. The peaks above are the zone of wild game, tur and bezoar goat.

Figure 36. Petroglyph of a bezoar goat on a cornerstone of a wall in the old settlement of Khushtada

Tributary river gorge eco-functional altitudinal zone (c. 1,100-1,600 m asl)

The zone below that of the central village and its cropland beside or through which its eponymous river flows down to the Koisu is usually steep and sparsely vegetated, although there is sometimes sufficient growth to provide grazing for the hardy small mountain cattle and sheep. Water powered horizontal water mills were located near the village itself or lower down the tributary gorge [27]. Here corn and the grain grown locally or bought in regional markets in exchange for the village’s dairy products could be freshly milled, as well as the nutritious urbech, a delicious ground paste of nuts and seeds. A number of these mills still function along the tributaries of the Andiiskoe Koisu and are highly valued as essential ecosystem services locally.

Riverine terraced orchard eco-functional altitudinal zone (c. 1,000-1,100 m asl)

The lowest eco-functional zone is where the tributary river flows into the Koisu. Here irrigable rock-walled terraces provide soil for orchards of apricots and other fruit trees, grapevines and vegetable gardens which prosper better at the higher temperatures near the river. Bee hives are set in these orchards by individual households, producing a prized honey, another staple in the traditional dietary repertoire. The natural vegetation of this zone is xerophytic with the fruit and leaves of certain characteristic species being collected by locals as for food and medicines (Fig. 37). Apricots (endemic to this region) are split and dried as (kuraga) for domestic culinary uses (Fig. 38). Their kernels are milled into urbech. Excess production is sold to urban markets.

Figure 37. Gathering the tart yellow berries from the thorny branches of the sea buckthorn (облепиха) (Hippophae rhamnoides L) on the rocky banks of the lower Khushtadarinka River.

Figure 38. Drying apricots (kuraga) – a staple food of the communities of the Andiiskoe Koisu valley.

Traditional Agro-Pastoral Practices

Whereas for many millennia the staple crops of the Koisu highland communities were wheat and barley with some rye and oats, in the 19th century potatoes and corn were introduced and, after a 1950 state decree whereby wheat officially ceased to be sown in regional collective farms, these became the dominant field crops in the region, though wheat still continues to be grown in lesser quantities.

The Godoberi, Chamalal and Bagulal communities on opposite sides of the Koisu all follow the same sustainable agricultural and pastoral practices. They all raise the small Dagestan mountain cattle which provide milk, which is usually not drunk fresh but converted into a range of traditional dairy products, mainly sour cream, butter, tvorog, and hard and soft cheeses, including a staple type which is preserved in brine for year-round use. In the past, when a family’s cereal harvest was not sufficient for all its needs, butter, cheeses and hides were taken by donkey for exchange in regional market centres for grain. Steers are still used as draught animals for ploughing. They also provide meat which is air-dried outdoors in winter or made into sausages which are also air-dried. Cow hides were used to make boots and other items. The local fat-tailed Dagestan mountain sheep are raised for both their wool and meat. Slices of dried fat sheep tails (kurdiouk) are a favourite delicacy throughout Dagestan. Those communities which raise sheep and goats pasture them in the grasslands above the villages during the warmer months. They are then collected and driven as united flocks down to the coastal lowlands for the cold season. Chickens are also raised in coops near the houses.

Continuum of Sustainable Subsistence Agriculture

Nowadays, the highland communities of the Andiiskoe Koisu continue the sustainable agro-pastoral practices which have allowed them to subsist and prosper for millennia in their productive bioniches, belying urban notions that the peasant farmers of the high mountains eked out a living in remote and precarious hardship. K.-M. Khashaeva, in surveying historical agricultural practices in Dagestan, quoted a range of 19th century Russian travelers who were impressed by the productivity of many of these high altitude communities, “Nobody asks himself the question, how can one explain that the mountaineers from ancient times have remained in the mountains and are engaged in agriculture? Why is a hectare of land in the mountains valued as 10-15 times more expensive than on the plain? As is known in the mountains, from their field crops and horticulture in a good climate the mountaineers have received a goodly income and therefore from time immemorial have been engaged in them. … N. Voronov, describing the occupations of the inhabitants of a number of free mountain societies in 1868, noted that even the Dido people living in the high-mountainous part of Dagestan [adjacent to the upper Andiiskoe Koisu], “sow … barley, wheat, very rarely beans; at harvest the grain itself produces 15 – 20 fold.” Such a harvest was not obtained even on “the best lands of the Dagestan plains.” [28] S. Bronevsky in 1823 wrote that the highlanders sow grain on high mountains, where cultivated fields are often found “on rolling contours, which usually bring rich harvests.” producing more than 40 sabs per household and 12 sabs per person per year, that is, an average of one pound of grain per person per day [29]. [Chamalal] Gidatli has long been famous in Avaria for an abundance of bread and meat and therefore is called a fertile land.” [30]

The Soviet system brought with it a change from traditional land ownership regimes, which had continued under the Tsars, to control by state collectives. However, traditional practices of land use themselves did not basically change and, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, continue to the present day. The agriculture and pastoralism now practiced in the high altitude communities described here have no negative impact on the environment. Manure from cattle (collected from domestic cattle byres) and sheep (let onto fields in fallow or after harvest to feed, their droppings acting as fertilizer) are exclusively used as fertilizers and no pesticides are required. The land still continues to be ploughed with the traditional iron-shared wooden plough drawn by cattle, although petrol-driven rotary cultivators are becoming more and more popular. Now that all-weather gravel roads are opened to most settlements, the long-essential donkeys are only used for access to locations unreachable by motor vehicles.

Impacts of Changes in Modern Life Style of Rural Communities on the Natural Environment: Waste Management

The built environment of highland villages across the district is changing markedly as people convert old houses, build new ones and outfit them in a contemporary global style. These dwellings have modern bathrooms, laundries and kitchens without the household systems or the proper community infrastructure to process liquid waste in an environmentally appropriate way. Added to this burden on the local environment is the significant problem of the disposal of plastic waste. As all of the highland communities live above a tributary river, both liquid and plastic waste present a risk to the riverine communities and ecosystems downstream (Figs. 44 & 45).

Verkhnee Gakvari School Programme of Ecological Education

A substantial component of the ongoing research of the “Conserving the Koisu” project has been focused on understanding how these communities of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu have managed, from generation to generation, to continue to effectively sustain both the concepts and practice of an ecological balance with the surrounding environment.

The stimulus to pursue this direction of research within the framework of a Socio-Ecological Production Landscape Case Study for the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative arose from the exemplary education in both theoretical and practical ecology provided over a period of some 50 years to students at the school of the Chamalal community of Verkhnee Gakvari in the Tsumadinsky District and the positive impact this has had on community engagement in environmental management.

Collaborative research with those responsible for this educational programme has revealed how in these ethnolinguistic enclaves over hundreds of generations this concern for the environment has been transmitted through successive forms of structured education:

- (a) customary law or social mores (known as adat) formulated within the context of community held polytheistic religious beliefs both about the ever-evident powers of nature in this environment and the responsibility to protect it.[31] Adat strictly regulated and enforced proper land use in community territory, including under what conditions fields could be manured, when land could be ploughed and crops harvested [32].

- (b) Islamic doctrines embodied in the Quran and hadith which prior to and after the Soviet period have been transmitted through values-based teaching in local mosques and households in Muslim communities throughout the Koisu, which repeatedly stresses the obligation for believers to use the environment and treat all creations with respect and without wastefulness, mirroring modern concepts of biodiversity conservation and sustainable use of natural resources; [33] [34] These teachings continue.

- (c) state public education in Soviet period primary and secondary schools which provided empirical scientific education about biotic and abiotic resources and the fundamentals of agronomy and food production; and

- (d) state public education in modern Russia which places ecological education as a core element of the primary and secondary school curriculum.

During the Soviet period a state forestry service was established in the Tsumadinskiy District to care for its extensive forest reserves. Acquaintanceship with professional foresters working nearby led two teachers of the Verkhnee Gakvari school with a background in ecology and biology to establish a school forestry around 1970. This was in operation until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1990. However, its legacy amongst ex-students in the community and new teachers who were also interested in ecology and biology, led to an ecology-orientated organization, the Edelweiss Eco-Group being established at the school in 2009. This group is actively engaged in monitoring, caring for and promoting awareness of features of the environment of importance to the Verkhnee Gakvari and district community, including three water sources locally-valued for their medicinal properties. The group also works to improve and green locations in the settlement and collects wild medicinal plants for local us

Figure 39. Verkhnee Gakvari in autumn viewed viewed from the adjacent Ginkili Forest and Pine Grove in the care of the Berezka School Forestry.

Figures 40 & 41. Students of the Berezka School Forestry monitoring forest growth and preparing soil in the arboretum nursery.

During the Soviet period a state forestry service was established in the Tsumadinskiy District to care for its extensive forest reserves. Acquaintanceship with professional foresters working nearby led two teachers of the Verkhnee Gakvari school with a background in ecology and biology to establish a school forestry around 1970. This was in operation until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1990. However, its legacy amongst ex-students in the community and new teachers who were also interested in ecology and biology, led to an ecology-orientated organization, the Edelweiss Eco-Group being established at the school in 2009. This group is actively engaged in monitoring, caring for and promoting awareness of features of the environment of importance to the Verkhnee Gakvari and district community, including three water sources locally-valued for their medicinal properties. The group also works to improve and green locations in the settlement and collects wild medicinal plants for local use.

In 2010, the Bereska School Forestry was established at the Verkhnee Gakvari school in agreement with the Tsumadinsky State Forestry Enterprise, which assigned it nearby forest areas to carry out forestry activities. The school forestry undertakes research into the forest environment and all aspects of professional forestry management of the three forest areas under its care: the Ginkili Forest (and recreational forest glade used by visitors), the Tsanatli Forest and a Pine Grove planted by the initial school forestry within the indigenous endemic birch forest. It is fully equipped with all the necessary classrooms, workshops and equipment. There is also a school nursery and arboretum in which seedlings for forest regeneration are grown and which also serves for experimentation. (Figs. 38-41)

Figure 42. Students and teacher planting saplings which they have grown from seeds they collected Berezka School Forestry. Verkhnee Gakvari school.

Figure 43. Students measuring the growth of apple trees in the Verkhnee Gakvari school orchard.

Figure 44. Students of the Verkhnee Gakvari’s school’s Edelweiss Eco-Group and teachers retrieving waste from the Gakvarina River.

These school organisations are also responsible for identifying and protecting local vegetational features and for promoting their designation as natural monuments of rural municipal importance. They are very active, and successfully so, in regional and republican level school competitions relating to ecology and care of the environment. The end result is not only a cadre of school students with a solid basis of ecological education but a broader community which is fully aware of the importance of being involved in environmental management. Members of the community are now taking the initiative in devising ecologically appropriate systems for a public sanitation infrastructure and waste management – an extremely challenging endeavor which is considered to be the priority necessity. In this regard, students are working with the village administration to address the challenges of properly collecting and disposing of domestic waste. (Fig. 44)

Figure 45. Hectares of plastic and other waste floating on the surface of the Andiiskoe Koisu near its confluence with the Avarskoe Koisu to form the Sulak River.

Figure 46. Speakers at the 2017 Agvali scientific-practical conference, “The Ecology of the Mountain Territories: Problems and Pathways to their Resolution.”

Besides activities directed at the education of local students and community, school personnel are also dedicated to advancing advocacy of the need for communal environmental management within the broader Tsumadinskiy District and at the republican level. In 2010, they organized in Verkhnee Gakvari a scientific-practical conference in Verkhnee Gakvari, “Ecology of the Tsumadinskiy District: Problems and Pathway to Their Solution” and in 2017 another scientific-practical conference, “Ecology of the Mountain Territories of Dagestan: Problems and Pathway to Their Solution”, which was held in Agvali. Specialists from Makhachkala (including the Institute of Ecology and Sustainable Development of Dagestan State University [DSU]) and three other mountain districts (Akhvakhskiy, Gumbetskiy and Botlikhskiy) took part and drew up resolutions for further action which has formed the framework for the goals of the current “Conserving the Koisu” project [32]. (Figs. 45 & 46)

Conclusion

Although today’s communities of the Tsumadinskiy District continue to follow the sustainable agricultural and pastoral practices of the past with no negative impact on the environment or threat to the carrying capacity of their traditional lands, these only suffice to support a local population of about the size which it had in past generations. The territory of Verkhnee Gakvari, for example, cannot economically or in terms of environmental balance support a population of more than the approximately 400 souls who live there today, a figure which has not substantially varied since records were kept following the Tsarist conquest. However, as populations in the region have grown considerably in modern times, more than can be supported by the regional economy, there is a considerable exodus of who have had to leave to find work elsewhere, either seasonally as workers in agriculture or other sectors in the coastal plains or to live and work permanently in the capital, Makhachkala, the lowland Dagestan urban centres of Kizilyurt, Khazavyurt and Kizlar or in expatriate ethnolinguistic communities in neighbouring Chechnya.

Thus, there is a situation, whereby, although agro-pastoral systems are continuing to function in ways which are ecologically sustainable and in harmony with the environment – thus preserving the traditional socio-ecological production landscape, the region as a whole is not economically sustainable and is largely reliant on monies flowing from state government to fund essential services and infrastructure and on expatriate and diaspora incomes for any developmental initiatives.

Dagestan State University is engaged in cooperation with local communities and government entities in working towards concrete responses to alleviate this situation. This is being done through both its (a) Conserving the Koisu project which is identifying the ecological and cultural heritage resources of the region and how these can be protected and be drawn upon to contribute to its sustainable economic development, and (b) its University of the People policy which is addressed at co-engagement with the society of the Tsumadinskiy District to draw on local knowledge and expertise to identify and support educational needs from primary to tertiary education and further and in-service education for adults in ways which will serve the goals of sustainable development [33].

FIGURES

Figure 1 Topographical map showing location of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu and its valley (large black box) and of Godoberi, Chamalal and Bagulal community territories (small black box). Soviet military map 1:500,000, 1942 (Grozny – sector K-38-Б). The inset shows the location of the Tsumadinskiy District in the Republic of Dagestan. The Godoberi territories are in the adjacent Botlikhskiy District to the north.

Figure 2 Panoramic view south from Botlikh of the Godoberi territories of Nizhnee Godoberi and Verkhnee Godoberi situated on the Zhaloo Ridge in the midst of croplands with forests above and mountain pastures at a higher elevation on the right. The gorge on the left is that of the entry to the upper Andisskoe Koisu.

Figure. 3 View of the other side of the ridge shown in Figure 2, where the gorge of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu slices through the great ramparts of the Niguli Meidan and the Zhaloo Ridge (in the background). The croplands of Bagulal Gimerso are in the foreground with Kvanada behind. Across the Koisu can be seen the sloping lands of Gigatli.

Figure 4 Relief map showing highland settlements on both flanks of the Andiiskoe Koisu referred to in text. Right flank – Bagulal territory: Khvanada (Кванада), Gimerso (Гимерсо), Tlondoda (Тлондода) and Khushtada (Хуштада). Left flank – Godoberi territory: Nizhnee Godoberi (Нижнее Годобери) and Verkhnee Godoberi (Верхнее Годобери). Chamalal territory: Gigatli (Гигатль), Gadiri (Гадири), Nizhnee Gakvari (Нижнее Гаквари), Verkhnee Gakvari (Верхнее Гаквари), Gigikh (Гигих) and Richaganikh (Ричаганих). At the riverine level are the Chamalal communities of Gigatli Uruk (Гигатль Урук), Agvali (Агвали) and Kochali (Кочали). The inset shows the areas of glaciation and periglaciation of the upper Andiiskoe Koisu during the Last Glacial Period (after https://doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-444-53447-7.00012-X).

Figure 5 Topographical map with contours showing relief configuration of the territory of Nizhnee Godoberi and Verkhnee Godoberi, including the forested areas backing the croplands. Soviet military map 1:100,000, 1984 (Botlikh sector k-38-57).

Figure 6 View from the west of the Bagulal settlement of Khvanada and its distinctive land form. Below flows the Andiiskoe Koisu.

Figure 7 The settlement of Khvanada in early winter after the crops have been harvested.

Figure 8 Topographical map with contours showing relief configuration of the territory of the Bagulals in the Tsumadinskiy District: Khushtada, Tlondoda, Kvanada and Gimerso including the forested areas backing the croplands. Soviet military map 1:100,000, 1984 (Botlikh sector k-38-57).

Figure 9 View of the Bagulal territory of Khushtada from the west.

Figure 10 Winter view from croplands below the village of Khushtada towards the ruins of the old village (centre) and the territory of Tlondoda community on the opposite side of the Khushtadarinka River.

Figure 11 The dense pine forest above the Khushtada settlement. The district administrative centre of Agvali can be seen below on the bank of the Andiiskoe Koisu. The Zhaloo Ridge escarpment is the border between the Godoberis and Chamalals

Figure 12 View westwards from below the settlement of Khushtada encompassing the Chamalal territories of Gigikh, Kochali, Agvali, Gadiri and Gigatli.

Figure 13 View westwards to the territory of Gadiri situated high above the Gadirinka River.

Figure 14 Topographical map of the Chamalal territories on the left flank of the Andiiskoe Koisu valley. Soviet military map 1:50,000,1984 (Botlikh sector k-38-57).

Figure 15 Figure.14. View from pastures above Gidatli to the village and the Zhaloo Ridge.

Figure 16 View eastwards of the forest, fields and abandoned village of Verkhnee Gigikh with its distinctive landform. Note the settlement of Gigikh below located nearer the level of the Andiiskoe Koisu.

Figure 17 The village of Gigikh. An example of the deep soils supporting agriculture in these high-altitude communities.

Figure 18 View eastwards from the Snegovoy Ridge over the territories of Verkhnee Gakvari and Nizhnee Gakvari across the Andiiskoe Koisu to the peaks of the Bogossky Ridge. Note forests on the right flank of the Gakvarinka River near the upper village.

Figure 19 Elevations of principal highland settlements of the Godoberis, Chamalals and Bagulals.

Figure 20 The village of Verkhnee Gakvari in early summer.

Figure 21 Village of Verkhnee Gakvari in early autumn in the midst of its croplands after the harvests and haymaking. The Verkhnee Gakvari school is the long building painted blue and white below the minaret.

Figure 22 Generalised schematic of eco-functional zones according to altitude of the high mountain communities on either flank of the norther upper reaches of the Andiiskoe Koisu.

Figure 23 A pair of the local small mountain cattle pulling a plough in a field adjacent to the village of Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 24 Tending young potato plants in a field near the village, Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 25 Harvesting potatoes in a field near the village of Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 26 Harvesting carrots near the village. Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 27 Cutting hay above the croplands. Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 28 Gathering hay to be taken and stored as winter fodder. Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 29 Donkeys equipped with wooden saddles for transporting hay. Verkhnee Gakvari. .

Figure 30 Wooden domestic storage ambar. Gadiri.

Figure 31 A watering place for sheep, goats and cattle in the pasture zone above the village of Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 32 Evening milking in a traditional cow byre.

Figure 33 Cooperative building of a corral in the grassy pasture zone above the village. Verkhnee Gakvari.

Figure 34 Fat-tailed Dagestan mountain sheep grazing on the slopes below the settlement of Khushtada. Zhdoo Ridge in background.

Figure 35 Winter view of Tlondoda (note minaret in upper left) westwards to the Snegovoy Ridge. The long snowy valley is that of the Gakvarinka River and the territories of Verkhnee Gakvari and Nizhnee Gakvari. The peaks above are the zone of wild game, tur and bezoar goat.

Figure 36 Petroglyph of a bezoar goat on a corner stone of a wall in the old settlement of Khushtada.

Figure 37 Gathering the tart yellow berries from the thorny branches of the sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L) on the rocky banks of the lower Khushtadarinka River.

Figure 38 Drying apricots (kuraga) – a staple food of the communities of the Andiiskoe Koisu valley.

Figure 39 Verkhnee Gakvari in autumn viewed from the adjacent Ginkili Forest and Pine Grove in the care of the Berezka School Forestry.

Figures 40 & 41 Students of the Berezka School Forestry monitoring forest growth and preparing soil in the nursery prior to planting seeds of local forest species for their forest regeneration programme. Verkhnee Gakvari school.

Figure 42 Students and teacher planting saplings which they have grown from seeds they collected. Verkhnee Gakvari school.

Figure 43 Students measuring the growth of apple trees in the Verkhnee Gakvari school orchard.

Figure 44 Students of the Verkhnee Gakvari’s school’s Edelweiss Eco-Group and teachers retrieving waste from the Gakvarina River.

Figure 45 Hectares of plastic and other waste floating on the surface of the Andiiskoe Koisu near its confluence with the Avarskoe Koisu to form the Sulak River. It was brought down after heavy rains in the upper Andiiskoe Koisu.

Figure 46 Speakers at the 2017 Agvali scientific-practical conference, “The Ecology of the Mountain Territories: Problems and Pathways to their Resolution.”

REFERENCES:

[1] Атаев, З.В., 2012, Орография высокогорий Восточного Кавказа, Географический вестник, 2 (21), c.. 4-9.

[2] Магомедханов М.М., Ченсинер Р., Ченсинер М., Мусаева М.К., Гарунова С.М., 2020, Дагестан. Горно-долинное садоводство: Дефиниции «агрокультура», «хорткультура», «садоводство» История, археология и этнография кавказа, Том 16, № 3 (2020), pp.770-796.

[3] Petherbridge G., Ismailov M.M., Ismailov S.M., Rabadanov M.Kh., Gadzhiev A.A., Teymurov A.A., Rabadanov M.Kh., Rabadanov M.R., Daudova M.G. & Abdulaev A-G., 2021, Verkhnee Gakvari: the contribution of adat, religious beliefs and public education to collective environmental management in an agro-pastoral community in the Dagestan high Caucasus, South of Russia, Ecology, Development, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 145-179. https://doi.org/10.18470/1992‐1098‐2021‐3‐142‐179

[4] Gobejishvili R., Lomidze N. & Tielidze L., 2011, Late Pleistocene (Wurmian) Glaciations of the Caucasus, Developments in Quaternary Science, Vol.15, pp. 141-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53447-7.00012-X

Revaz, K., Koba, K., Kukuri, T. & Giorgi, C., 2018, Ancient Glaciation of the Caucasus. Open Journal of Geology, 8, pp. 56-64. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojg.2018.81004

[5] Alejnikov A. A. & Lipka O. N., 2016, Melting Mountains of Dagestan. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Moscow.

Ataev Z., 2018, Recent Glaciation of Bogossky Range, Proceedings of Dagestan State Pedagogical University, Natural and Earth Sciences, Vol. 12, No.2, https://doi.org/10:31161/1995-0675-2018-12-2-62-74.

[6] Tayumov M.A., Umaeva A.M., Abdurzakova A.S., Israilova S.A., Astamirova M.A.-M., Shahgireeve Z.I. , Magamadova R.S. & Umarov, R.M., 2018, The history of formation and ways of penetration of the relict dendroflora into Chechnya and adjacent territories, International Conference on Smart Solutions for Agriculture (Agro-SMART 2018), Atlantis Press, Advances in Engineering Research, Vol. 151, pp. 958-962.

[7] Magomedov A. M. & Ataev Z. V., 2005, The influence of orography on the climatic conditions of Bogossky mountain range in the Eastern Caucasus, Proceedings of the Geographical Society of the Republic of Dagestan, No. 33, pp. 164-165.

[8] Coudreau, M., Spring 2021, A healthy mountainous island surrounded by a sea of malaria: Ecology and War in the Caucasus, Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia, No. 4. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8381

Trajer, A.J., 2021, The potential persistence of ancient malaria through the Quaternary period in Europe, Quaternary International, 586, pp.1-13.

[9] Ryabogina N., Borisov A., Idrisov I & Bakushev M., 2019, Holocene environment history and populating of mountainous Dagestan (Eastern Caucasus, Russia), 2019, Quaternary International 516,111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.020

Korobkova G.F., 1999, Cycles of agricultural economy as seen from experimental and use-wear analysis of tools, in Anderson P.C. (ed.), Prehistory of Agriculture: New Experimental and Ethnographic Approaches, Monograph No. 40, Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles, pp. 188 & 189.

Kushnareva K. Kh., op. cit. p. 157.

Лисицына Г. Н., 1984, Проблема становления производящих форм хозяйства в свете новейших палеоэтноботанических исследований в Передней Азии, Краткие сообщения Института археологии, Вып. 180.

Лисицына Г. Н. , 1984, К вопросу о раннем земледелии в Южной Грузии, Человек и окружающая его среда, Тбилиси.

Hovsepyan R., 2015, On the agriculture and vegetal food economy of Kura-Araxes culture in the South Caucasus, Paléorient, 2015, vol. 41, No.1. pp. 69-82. https:// doi.org/10.3406/paleo.2015.5656

[10] Османов М -З.O., 1990, Формы традиционного скотоводства народов Дагестана в XIX – нач. XX в.м., 1990, c.30.

Troy C.S., MacHugh D.E., Bailey J.F., Magee D.A., Loftus R.T., Cunningham .P, Chamberlain A.T., Sykes B.C. and Bradley D.G., 2001, Genetic evidence for Near-Eastern origins of European cattle, Nature, 410 (6832), pp.1088–1091.

Kunelauri N., Gogniashvili M., Tabidze V., Basiladze G. & Beridze T., 2019, Georgian cattle, sheep, goats: are they of Near-Eastern origins?, Mitochondrial DNA Part B, 4:2, pp. 4006-4009. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2019.1688695

Scheu A., Powell A., Bollongino R., Vigne J.-D, Tresset A., Çakırlar C., Benecke N. and Burger J., 2015, The genetic prehistory of domesticated cattle from their origin to the spread across Europe, BMC Genetics, 16:54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-015-0203-2

Berthon R., Past, Current and Future Contribution of Zooarchaeology to the Knowledge of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic Cultures in South Caucasus, Studies in Caucasian Archaeology, Prof. Sergi Makalatia Gori Historical-Ethnographical Museum, 2014. ffhal-02136934

Ozdemirov A.A., Chizhova L.N., Khozhokov A.A., Surzhikova E.S., Selionova M.I. & Abdulmagomedov S.Sh., 2021, Polymorphism of genes CAST, GH, GDF9 of sheep of the Dagestan mountain breed, South of Russia: Ecology, Development, Vol. 16, No 2, pp. 34-44.

[11] Beja-Pereira A., England P.R., Ferrand N., Jordan S., Bakhiet A.D., Abdalla M.A., Mashkour M., Jordana J., Taberlet P. & Luikart G, 2004, African origins of the domestic donkey, Science 304, p. 1781.

Rossel S., Marshall F., Peters J., Pilgram T., Adams M.D. and O’Connor D., 2008, Domestication of the donkey: Timing, processes, and indicators, PNAS, March 11, Vol. 105, No. 10, pp. 3715–3720. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0709692105

[12] Амирханоv A., 1987, Чохское поседение. Человек и его культура в мезолите и неолите горного Дагестана, Института истории, археологии и этнографии, Дагестанского Научны Центр, РАН, Наука, Москва.

Kushnareva K. Kh., 1997, The Southern Caucasus in Prehistory: Stages of Cultural and Socioeconomic Development from the Eighth to the Second Millennium B.C., trans. Michael H.N, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, pp. 13-21.

Chataigner C., Badalyan R. & Arimura M., The Neolithic of the Caucasus, 2014, Oxford Handbooks Online, Subject: Archaeology, Archaeology of Central Asia Online. https://doi.org 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935413.013.13

Messager E., Herrscher E., Martin L., Kvavadze E., Martkoplishvili I., Delhon C. et al. 2015, Archaeobotanical and isotopic evidence of Early Bronze Age farming activities and diet in the mountainous environment of the South Caucasus: a pilot study of Chobareti site (Samtskhe–Javakheti region), Journal of Archaeological Science, 53, pp.214–26.

Karafet T.M., Bulayeva K.B., Nichols J., Bulayev O.A., Gurgenova F., Omarova J., Yepiskoposyan L., Savina O.V., Rodrigue B.M and Hammer M.F., 2015, Coevolution of genes and languages and high levels of population structure among the highland population of Dagestan, Journal of Human Genetics, pp. 1-11.

These researchers found “a significant positive correlation between gene and language diversity, with data consistent with the hypothesis that most Dagestanian-speaking groups descend from a common ancestral population (~6000–6500 years ago) that spread to the Caucasus by demic diffusion followed by population fragmentation and low levels of gene flow.”

See also:

Balanovsky O., Dibirova K., Dybo A., Mindrak O., Frolova S., Pocheshikova E. et al, 2011, Parallel evolution of genes and languages in the Caucasus region, Molecular Biological Evolution, 28, pp. 2905-2920.

Bulayeva K.B., Dubinin N.P., Shamov I.A., Isaichev S.A. & Pavlova T.A., 1985, Population genetics of Dagestan highlanders, Genetika, 21, pp. 1749-1758.

Bulayeva K.B., Jorde L., Watkins S., Ostler C, Pavlova T.A., Bulayev O.A., 2006, Ethnogenomic diversity of Caucasus, Dagestan, American Journal of Human Biology, 18, pp. 610-620.

Marchiani E.E., Watkins W.S., Bulayeva K., Harpending H.C. & Jorde L.B., 2008, Culture creates genetic structure in the Caucasus: autosomal, mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal variation in Daghestan, BMC Genetics, 47.

Margaryan A., Derenko M., Hovhannisyan H., Malyarchuk, B., Heller R., Khachatryan Z. Pavel A., Badalyan R., Bobokhyan A., Melikyan V., G., Piliposyan A., Simonyan H., Mkrtchyan R., Denisova G., Yepiskoposyan, L., Willerslev E., Allentoft M.E., 2017, Eight millennia of matrilineal genetic continuity in the south Caucasus, Current Biology, 27 (2), pp. 2023-2028.

Nasidze I, Sarkisian T., Kerimov A. & Stoneking M., 2003, Testing hypotheses of language replacement in the Caucasus: evidence from the Y-chromosome, Human Genetics, 112, pp. 255-261.

Yunusbayev B., Metspalu M., Jarve M., Kutuev I, Rootsi S., Metspalu E et al, 2011, The Caucasus as an asymmetric semipermeable barrier to ancient human migrations, Molecular Biological Evolution 29, 2011, pp. 359-365.

Wang C.-C., Reinhold S., Kalmykov A., Wissgott A., Brandt G., Jeong C. et al, 2019, Ancient human genome-wide data from a 3000-year interval in the Caucasus corresponds with eco-geographic regions, Nature Communications, 10(1), 590 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08220-8

[13] Knipper C., Reinhold S., Gresky J., Berezina N., Gerling C., Pichler S.L., et al, 2020, Diet and subsistence in Bronze Age pastoral communities from the southern Russian steppes and the North Caucasus. PLoS ONE 15(10): e0239861. https:// doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239861

[14] Шиллинг Е.М., Малые народы Дагестана, Москва, 1993.

Мусаева М. К.б Традиционная материальная культура малочисленных народов Западного Дагестана (Панорамный обзор), Институтом истории, археологии и этнографиии Дагестанского научного центра РАН, Издательский Дом «Народы Дагестана», Махачкала, 2003.

Дирр А., 1909, Материалы для изучения языков и наречий андо-дидойской группы, Сб. материалов для описания местностей и племен Кавказа, вып. 40, 1909. / Dirr A., 1909, Materials for studying of languages and dialects of Andic-Dido group, Collection of Materials for the Description of the Territories and Peoples of Caucasus, Vol. 40, Tbilisi.

Kolga M., 2001, Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire, NGO Red Book, Tallinn.

[15] Caciagli L., Bulayeva K., Bulayev, O. et al, 2009, The key role of patrilineal inheritance in shaping the genetic variation of Dagestan highlanders. Journal of Human Genetics, 54, pp. 689–694. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2009.94

[16] Gobejishvili R., Lomidze N. & Tielidze L., 2011, Fig. 12.1 (detail).

[17] Moseley, C., 2010, Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, 3rd ed., Paris, UNESCO Publishing. Online version: http://www.unesco.org/culture/en/endangeredlanguages/atlas

[18] French H., 2003, The development of periglacial geomorphology, 1-up to 1965, Permafrost and Periglacial Processes, 14, pp. 29-60.

Bondyrev I.V., Glacial and periglacial processes of Georgia, Геология и геофизика Юга России, № 4, 2013, УДК 551.30, pp. 51-62.

Hallet, B., 1979, A theoretical model of glacial abrasion, Journal of Glaciology, Vol. 23, pp. 39–50.

Hallet, B., 1996, Glacial quarrying: A simple theoretical model, Annals of Glaciology, Vol. 22, pp. 1–8.

Kirkbride, M., and Matthews, D., 1997, The role of fluvial and glacial erosion in landscape evolution: The Ben Ohau Range, New Zealand, Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, Vol. 22, pp. 317–327.

Spotila, J.A., Buscher, J.T., Meigs, A.J. and Reiners, P.W., 2004, Long-term glacial erosion of active mountain belts: Example of the Chugach-St. Elias Range, Alaska, Geology, Vol. 32, pp. 501–504.

[19] Алимова Б.М., Лугуев С.А., 1997, Годоберинцы: Историко-Этнографическое Исследование XIX- нач. XX века, Дагестанский Научны Центр РАН, Институт истории, археологии и этнографии, Махачкала.

Алимова Б.М., Магомедов Д.М., Годоберинцы, 1997, Народы Дагестана, Арутюнов С.А., Османов А.И., Сергеева Г.А.(eds), Наука, Москва, pp. 189-200.

[20] N.I. Vavilov, the renowned Russian agronomist and geneticist who specialized in identifying the origins of cultivated plants, described the area thus, “In Dagestan, near Botlikh, you can see amazing terraced farming, located many tens of levels in relation to the relief, huge amphitheatres. It is hardly possible to use the land better than is done in mountainous Dagestan.” Исламмагомедов, А., 2002, Аварцы: Историко-этнографическое исследование XVIII- нач. XX в, Институт истории, археологии и этнографии, Дагестанский научный центр, Российская академия наук, Махачкала, с. 71.

[21] Гаджиев Г.А., 1997, Народы Дагестана, Арутюнов С.А., Османов А.И., Сергеева Г.А. (eds), Наука, Москва, c. 169-179.

Алексеев М.Е., Багвалинский язык, Красная книга народов России, Москва, 1994./

Aleksejev M. E., Bagvalal, Red Book of the Languages of the Peoples of Russia. Encyclopaedia. Moscow,1994.

[22] Гаджиев Г.А., 1997, Народы Дагестана, Арутюнов С.А., Османов А.И., Сергеева Г.А. (eds), Наука, Москва, c. 222-230.

Гаджиев Г.А., 1989, Хозяйство и материальная культура багулалов, XIX- нач. XX в, // РФ ИИАЭ, Ф.З, Оп.3, Д.702m с. 82-87.

Гаджиев Г.А., 1990, Пища чамалалов в прошлом и настоящем // Система питания народов Дагестана (ХІХ-ХХ вв.), c. 50-57

Гаджиев Г.А., 1988, Поселения чамалалов в ХІХ- нач. XX в. // Материальная культура народов Дагестана XIX нач. XX в. Махачкала, c. 41-56.

Бокарев A., 1949, Очерки грамматики чамалинского языка, Москва-Ленинград.

Магомедбекова З. М., 1967, Чамалинский язык, Языки народов СССР, Т. 4: Иберийско-кавказские языки, Москва.

Магомедова П. Т., 1999, Чамалинский язык, Языки мира, Кавказские языки. Москва.

Алиева З. М., 2003, Словообразование в чамалинском языке, Махачкала.

Magomedova P. T., 2004, Chamalal, The Indigenous Languages of the Caucasus, Vol. 3: The North East Caucasian languages, Pt. 1, Ann Arbor.

Roncero K., An audiovisual corpus of Chamalal, a language of Daghestan, Preservicar/ELAR. Available at https://elar.scar.ac.uk/collection/MPI1234834. This deposit is a multi-dialect corpus (comprising both Gigatlian and Gakvarian Chamalal varieties). Together with the purely linguistic descriptions (a grammar sketch; an article on phonology; and another article on verbal morphology) the collection also includes literacy materials as well as written stories by Chamalal speakers, as product of the literacy programmes. The collection also includes testimonies of speakers describing the traditional lifestyle; marriage and family bonds; informal economy and economy of favours; traditional ecological knowledge (TEK); Chamalal music and small folklore genres. The videos contain time-aligned translations in Russian and English.

Blog. Discoverchamalal.wordpress.com

Discover Chamalal channel: youtube.com/channel/UCFjyandRq5fc8_b9nl7U5qw

Video documentations include: “V. Gakvari: Overview” – youtube/watch&v+gP-6BdL2P2A; “The Mill in N. Gakvari – youtube/watch?v,+hgvFltnuNGE & “Old Chamalal Lands” – youtube/watch?v-2FDbcKjQiSk

Roncero K., Gakvarian Chamalal: A brief grammatical sketch, in Koryabov Y. & Masisak T., The Caucasian Languages: An International Handbook, Vol. II, De Guyter Mouton (HSK Series). [forthcoming]

[23] Petherbridge G. et al, op.cit. Fig. 7, p. 147.

[24] Гулиашвили В.З, Махатадзе Л.Б., Прилепко Л.И., 1975, Растительность Кавказа, Наука, Москва / Gulisashvili V.Z., Makhatadze L.B., Prilipko L.I., 1975, Vegetation of the Caucasus Nauka, Moscow. See also: rusnature.info/reg/15.6.htm [in Russian]

[25] For a good drawing of a characteristic Andiiskoe Koisu ambar (in this case from Karata-Botlikh) with plans and details of construction see Мовчан Г. Я., 2001, Старый аварский дом в горах Дагестана и его судьба (По материалам авторских обследовании 1945-1964 гг.), ДМК Пресс, Москва, Fig. 62.

[26] Among the edible and medicinal plant species utilised locally are:

- In the lowest zone near the Koisu: crown of thorns (Paliurus spina-christi), squirting cucumber (Ecballium elaterium), milkvetch (Astragalus membranaceus) and sea buckthorn Hippophae rhamnoides L.

- The slopes of the steep tributary gorges and the forests above provide: dog rose (Rosa canina), viburnum (Viburnum opulus L), spindle tree (Euonymus verrucosus Scop) and spurge laurel (Daphne mezereum), nettle (Urtica dioica), raspberry (Rubus idaeus), coltsfoot (Tissilago farfara), broadleaf plaintain Plantago major, chamomile (Matricaria chamomile), rowan (Sorbus aucuparia), yarrow (Achillea millefoilium), St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), oregano (Origanum vulgara), mint (Mentha ), European blueberry Vaccinium myrtillus L., thyme (Carum carvi), etc.

- On the northern slopes above the forests: the European blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus ) and the Caucasian rhododendron (Rododendron caucasium).

Bussman R.W., Batsatsashvili S., Tchelidze D., Paniagua Zambiana K.V., Ethnobotany of the Caucasus – The Region, in Bussman R.W. (ed.), European Ethnobotany, Springer, Cham. http:doi.org10.1007/978-3-319-49412-8_17

Турова А.Д., Сапожников Э.Н., 1984, Лекарственные растения СССР и их применение, 4-е изд, Москва.

Галкин М.А., Казаков А.Л., 1980, Дикорастущие полезные растения Северного Кавказа. Ростов-на Дону.

It should be noted here that ethnolinguistic minorities without a written form of their language may maintain unique oral nomenclature and other information about wild plants locally used as medicines or foods which do not exist in the general lingua franca of their region (in this case Russian or Avar).

See:

Gorenflo L. J., Romaine S., Mittermeier R.A. and K. Walker-Painemilla K., 2012, Co-occurrence of linguistic and biological diversity in biodiversity hotspots and high biodiversity wilderness areas, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 109(21). pp. 8032-8037.

Harmon, D., 1996, Losing species, losing languages: Connections between biological and linguistic diversity, Southwest Journal of Linguistics, 15, pp. 89 -108.

Pieroni A., Soukand R. and Bussmann R.W., The Inextricable Link Between Food and Linguistic Diversity: Wild Food Plants among Diverse Minorities in Northeast Georgia, Caucasus, Economic Botany, XX(X), 2020, pp. 1–19.

Sõukand, R. and Pieroni A., 2019, Resilience in the mountains: Biocultural refugia of wild food in the Greater Caucasus Range, Azerbaijan, Biodiversity and Conservation, 28, (13), pp. 3529-3545.

[27] Петербридж Г., Октябрь 2019, Производство главных продуктов горной жизни: Размышления об исламе, агротехнологиях и экологии на Кавказе и в Закавказье, Ас-Салам.

Гасанов М.Р. К истории водяной мельницы в Дагестане, Вестник института ИАЭ, 2007. № 2. с. 90 – 99.

[28] Хашаев K.-М., Занятия населения Дагестана в XIX веке, Академия наук СССР, Дагестанский филиял, Махачкала, 1959, с. 29, 40)

[29] Воронов Н.И., Из путешествия по Дагестане, Сборник сведений о кавказких горцах, Вып.1, 1868, с. 13.

[30] C. Броневский, Новейшие географические и исторические известия о кавказеб Ч.1юМ., 1823, с. 278.

[31] Гаджиев, Г.А., 1991, Доисламские верования и обряды народов нагорного Дагестана, Институтом истории, языка и литературы Дагестанского филиала АН СССР, Наука, Москва.

Magomedhabib Seferbekov, 2016, Notes on mountain cults in Dagestan, Iran and the Caucasus, Iran and the Caucasus, 20 (2), pp. 215-218. https://doi.org/10.1163/1573384X-20160205

Магомедова, Р. М., Гамзатова, П. А., Magomedova, Р.М., Gamzatova, П.А., 2014б

Развитие религиозных верований народов западного Дагестана (на примере Чамалалалов)/The development of religious beliefs of the peoples of western Dagestan (the example of the Chamalals), Гуманитарные, созиально-экономические и общественные науки, УДК 327, 2, с. 276-278. [in Russian]

Народы Дагестана, 1997, Арутюнов С.А., Османов А.И., Сергеева Г.А.(ред.), Наука, Москва, c. 230.

[32] Исламмагомедов, А., 2002, Аварцы: Историко-этнографическое исследование XVIII- нач. XX в, Институт истории, археологии и этнографии, Дагестанский научный центр, Российская академия наук, Махачкала, c. 64-92. This author provides detailed information about community requirements in Avar communities in central Dagestan for the exclusive and proper use of lands within their domains.

Агларов А.М., 1988, Сельская община в нагорном Дагестане в XVII — нач. XX в. (исследование взаимоотношения форм хозяйства, социальных структур и этноса), Наука-Дагестан, Махачкала, 1988.

Агларов М.А., 1981, Территории сельских обществ и их союзов горного Дагестана в XIV–XIX вв. // Общественный строй союзов сельских общин Дагестана в XVIII — начале XIX в. Махачкала.

Бобровников В.О., 2002, Мусульмане Северного Кавказа: Обычай, право, насилие. Очерки по истории и этнографии права Нагорного Дагестана. Москва.

[33] An excellent source of information about Islam and the environment is the Faith for Earth Initiative of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) which has launched a global push to bring together Islamic institutions from around the world in a bid to combat pollution, climate change and other threats to the planet. Called Mizan, Arabic for “balance”, the UNEP states that charter is designed to showcase Islam’s teachings on the environment and spur the world’s 1.8 billion Muslims to embrace sustainability as part of their everyday lives. See https://www.unep.org/al-mizan-covenant-earth

See also:

Mian H.S., Janas Khan J. & Rahman A.U, 2013б Environmental Ethics of Islam, Journal of Culture, Society and Development, Vol.1, pp. 69-74.

An Islamic Toolkit on Forest Protection: Resources for Religious Leaders and Communities, 2019, The Interfaith Rainforest Initiative, UN Environment Programme.

Bakar, O., 2007, Environmental Wisdom for Planet Earth: The Islamic Heritage, Centre for Civilizational Dialogue, University of Malaya Press, Kuala Lumpur, 2007.

Deen, M. Y., 2000, The Environmental Dimensions of Islam, The Lutterworth Press.

Ozdemir, I., 2003, Towards an Understanding of Environmental Ethics from a Qur’anic Perspective, Islam and Ecology, A Bestowed Trust, Oxford.

Norah bin Hamad, Foundations for Sustainable Development: Harmonizing Islam, Nature and Law (July 2017) (SJD dissertation, Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawdissertations/20/

Бобровников В.О., 1997, Ислам и советское наследие в колхозах Северо-Западного Дагестана // ЭО, № 5.

Бобровников В.О., 2006, Изобретение исламских традиций в дагестанском колхозе // Расы и народы. Москва, Вып. 31.

Агларов М.А., 1981, Территории сельских обществ и их союзов горного Дагестана в XIV–XIX вв. // Общественный строй союзов сельских общин Дагестана в XVIII — начале XIX в. Махачкала.

Из истории права народов Дагестана: Материалы и документы, 1968/Сост. А.С. Омаров. Махачкала.

Карпов Ю.Ю., 2014, Личность и традиционные социальные институты: принципы взаимодействия // Северный Кавказ: Человек в системе социокультурных связей. СПб.

Лугуев С.А., 2001, Традиционные нормы культуры поведения и этикет народов Дагестана (XIX — начало XX в.). Махачкала.

[34] The thoroughness of the traditional Islamic educational system in the Andiiskoe Koisu region is highlighted by the contributions of a Russian scholar, A. K. Serzhputovsky, at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. See: Зелбницкая Р. Ш. & Усенова С.Р., Из истории российскикх мусулман, Артефакты с арабским писмом в коллекциях каратинцев, дидойцев и ботлихцев в собрании российского этнографического музе, Ислам в современном мире, 2018, Том 14, № 1. https://doi.org/10.22311/2074-1529-2018-14-1-55-70.

See also:

Ярлыкапов А. А., 2003, Исламское образование на Северном Кавказе в прошлом и в настоящем, Вестник Евразии, 2003, № 2(21), pp. 11. / Yarlykapov A.A., 2003 Islamic education in the North Caucasus in the past and in the present, Bulletin of Eurasia, No. 2 (21).

Услар П.К., 1870, О распространении грамотности между горцами // ССКГ, Вып. 3.

[36] Petherbridge G., Gadzhiev A.A., Rabadanov M. Kh., Teymurov A.A., Murtazali R. Rabadanov M.R. and Abdulaev A.-G. M., The Third Mission of Dagestan State University: An Innovative Approach to Sustainability Policy. [forthcoming]