Promotion of Community Resilience and Rights in Competing Landuse: Case Study of Atwima Mponua and Asutifi North Districts in Ghana

12.06.2024

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

Resource Conservation Initiative (RESCONI)

DATE OF SUBMISSION

May 2024

Region

Africa

Country

Ghana

KEYWORDS

Cocoa, Farming, Land Use, Mining, Resilience, Rights

AUTHOR and AFFILIATIONS

Kwabena Akyeampong Boakye1*, Fredua Agyeman1, Isaac Kwabena Osei1, Raymond Owusu-Achiaw2, Larry Akpalu1, Kingsley Severine Fitz-Gerald3

1Resource Conservation Initiative (RESCONI), Ghana

2Conservation Alliance International, Ghana

3Proforest-Africa Region, Ghana

*Corresponding Author: Kwabena Akyeampong Boakye – kboakye@resconi.org

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Abstract

In Ghana, land is an essential natural resource that underpins economic growth and development through its utilization for farming, mining and as a forest resource. However, farming continues to be the mainstay of the economy, providing employment and livelihoods for many individuals and communities. The forest also serves as a source of timber, employment opportunities, and non-timber forest products, such as fruits, nuts, and medicinal plants, among others. Ghana’s forests are home to diverse wildlife, unique landscapes and cultural heritage sites which attract tourists and nature enthusiasts. Mining on the other hand, provides foreign exchange and revenue for government and local employment and offers economic growth, development and general prosperity. However, the negative effects of the utilization of the forest resources (e.g. illegal logging), and socio-economic and environmental implications associated with illegal mining necessitate the need for balance such that mining and the utilization of the forest resources are undertaken in a sustainable and environmentally friendly manner. This will ensure that the exploitation of these resources does not benefit only this present generation but also the future generations. The study adopted a concurrent mixed-methodological approach to examine the competing interest between farming, mining, and forest resources utilization in Asutifi North District and Atwima Mponua District in the Ahafo and Ashanti Regions of Ghana respectively. The study revealed through spatial evidence, stakeholder engagements and communities surveys that the forest cover has dwindled over the past 30 years. It also revealed that significant proportion of the community consisted of farming households with very few mining households. The major threat to the sustainability of the environment and socio-economic development of the local impacted communities was attributable to mining rather than farming. The study further highlighted the urgent need to balance farming, mining and forest resources utilization in the project districts in order to ensure sustainability, social inclusiveness and economic development. Therefore, the study recommends a human and environmental centred approach to address the threats from illegal forest exploitation and mining to safeguard the ecological integrity of the project landscapes for sustained and improved agriculture production and socio-economic wellbeing of the local communities.

1. Introduction

Land resources (including agricultural lands, forests, natural habitats and minerals) are critical for Ghana’s economic growth and a source of revenue and local livelihoods. The agriculture, forestry and minerals sectors account for more than 20 percent of Ghana’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP)[1]. In particular, cocoa, a predominant commodity in agriculture, accounts for 7 percent of GDP and about 20 – 25 percent of export earnings[2]. According to the World Bank, national accounts data and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), for 2022, agriculture, forestry and fishing accounted for 18.8% of Ghana’s GDP. In addition, as per the Ghana Statistical Service (2023), the solid minerals sub-sector contributed to 7.6% of Ghana’s GDP in 2023.

In recent times, Ghana has been confronted with the severe risk of environmental catastrophe due to the high levels of environmentally unfriendly human activities such as illegal mining and logging, chainsaw lumbering and farming within its forest reserves[3]. This phenomena of illegal mining and illegal logging equally extends into the Outside Forest Reserve (OFR)[4]. While these activities are not new, evidence indicates that the extent at which these activities are being perpetuated, they might sooner than expected, wipe away all of the country’s forests. In an effort at creating awareness for cross-sectoral links for sustainable exploitation of natural resources and promotion of sustainable land-use, improved agricultural production and adoption of appropriate management practices that addresses forest and biodiversity loss in Ghana, the Resource Conservation Initiative (RESCONI) applied for a grant from Ford Foundation. The project titled “Support to Promote Community Resilience and Rights in Competing Land Use for Mining, Agriculture and Forest Utilization in Ghana” was subsequently commenced in September 2022 and closed out in November 2023.

It is a well-established fact that biodiversity loss caused by illegal logging and mining and its associated illicit trade have caused significant and, in some cases, irreversible damage to the biodiversity resources of the country. The tremendous scale and impact of this loss of biodiversity and forest resources needs to be critically explored as it risks destroying entire ecosystems that many landscapes rely upon for their food sources, economies and livelihoods. Additionally, they have potential negative consequences on the communities and exert impacts that stimulate climate change. Presently, biodiversity loss is a serious threat and Ghana is committed to tackling it in all forms through its national strategies and action plans. These include the Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy 2012, the Forestry Development Master Plan (2016 – 2036), the Ghana REDD+ Strategy (2016-2035), the Ghana Forest Plantation Strategy: 2016-2040, Forest Investment Programme (FIP) (Enhancing Natural Forests and Agroforest Landscapes) and the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (2016). Thus, all landscape intervention activities on natural resource management, utilization and governance are expected to contribute to these national strategies and action plans and other relevant international and regional conventions, frameworks and commitments.

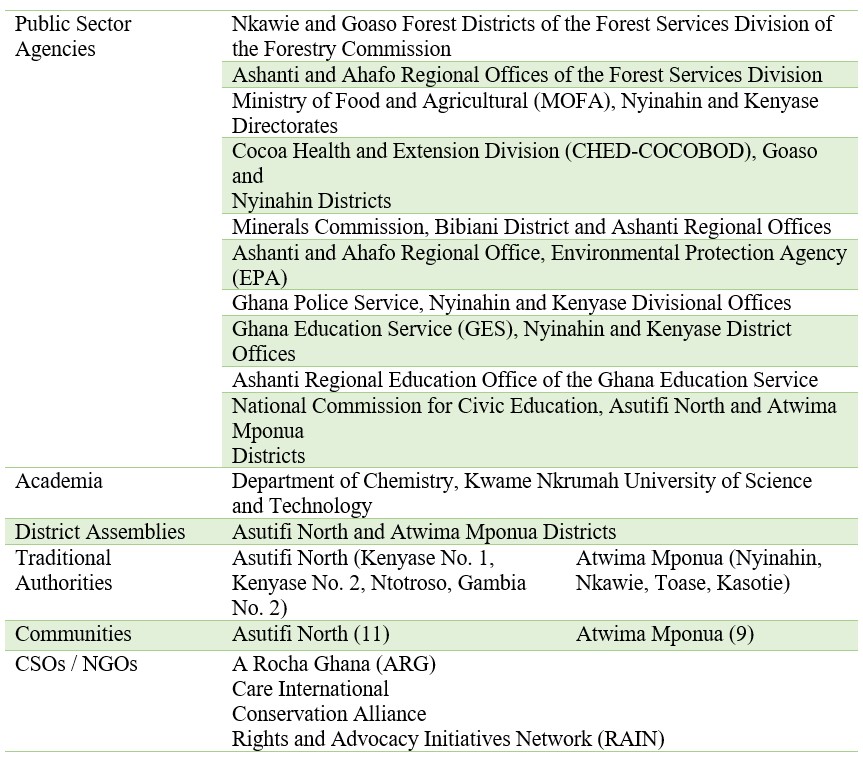

The project “Support to Promote Community Resilience and Rights in Competing Land Use for Mining, Agriculture and Forest Utilization in Ghana” undertaken in 2022-2023 with funding from Ford Foundation is a similar effort to address forest degradation and biodiversity loss. The project adopted a multi-stakeholder approach comprising public sector agencies, academia, private sector, traditional authorities, communities and CSOs/NGOs with stake and interest within the project sites to undertake interventions centred on community education, ecosystem restoration and green alternative livelihoods (Table 2).

RESCONI is presently undertaking several interventions in the project landscapes. One of these is the involvement of twenty (20) participating communities of the two (2) project locations to undertake restoration of 175 ha of degraded areas in the landscape under a project titled “Reforestation of degraded lands and riverine vegetation for improved climate resilience.” This Project is funded by One Tree Planted for TerraFund for AFR100 Program. The project aims to undertake restoration activities with indigenous species on degraded lands in the project communities. The goal is to increase shade trees on cocoa farms and enhance carbon stocks in the cocoa landscapes. The project also seeks to develop the capacity of the local institutions and communities for improved governance and decentralized forest and wildlife management. Further, the goal is to facilitate formation of environmental clubs for awareness on climate impacts and vulnerability and ameliorate microclimate and biodiversity conservation as well as facilitating the set-up of alternative livelihoods interventions. The number of tree seedlings to be planted by December 31, 2029 is 70,000 and the prescribed indigenous seedlings consist of Mansonia altissima, Khaya senegalensis, Terminalia superba, Terminalia ivorensis and Triplochiton scleroxylon. Importantly, these tree seedlings shall be planted in 2024 and 2025 planting seasons and shall be under a six-year monitoring regime from the first year of planting till project handing over scheduled for 31st October 2029. These projects are contributing towards the achievement of global initiatives including UN Decade of Restoration, SDGs 1, 2, 13, 15 and 17 and the global vision of Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework for living in harmony with nature by 2050.

[1]Ghana Statistical Service (2020) Annual Agriculture Production Statistics – January 2020. Agriculture accounts for 18.5% of

GDP, with food crops, cocoa and forestry accounting for 81.2% of sectoral output.

[2] 3rd Ghana Economic Update. Agriculture as an Engine of Growth and Job Creation, World Bank, 2018.

[3]A forest reserve means a protected forest land constituted under section 17 of the Forest Ordinance (CAP 157) that sets the

limits and situation of the land constituting it and published in the Gazette.

[4] Outside Forest Reserve (OFR) refers to timber production areas outside of the gazetted forest reserves.

2. Methodology

2.1 Study Area

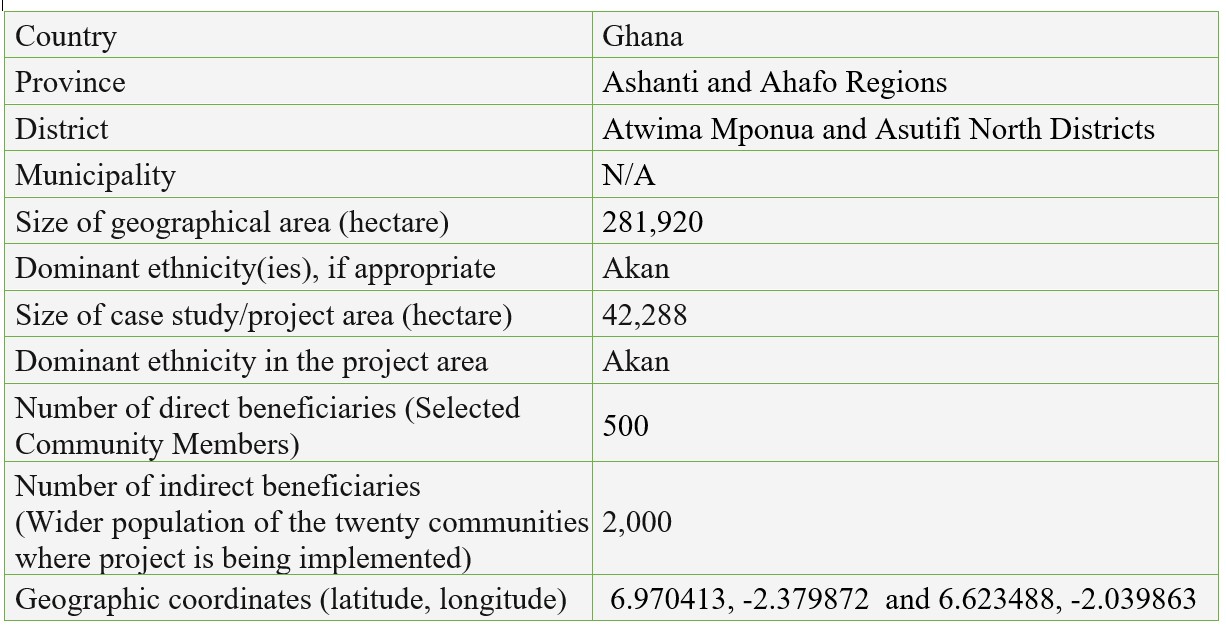

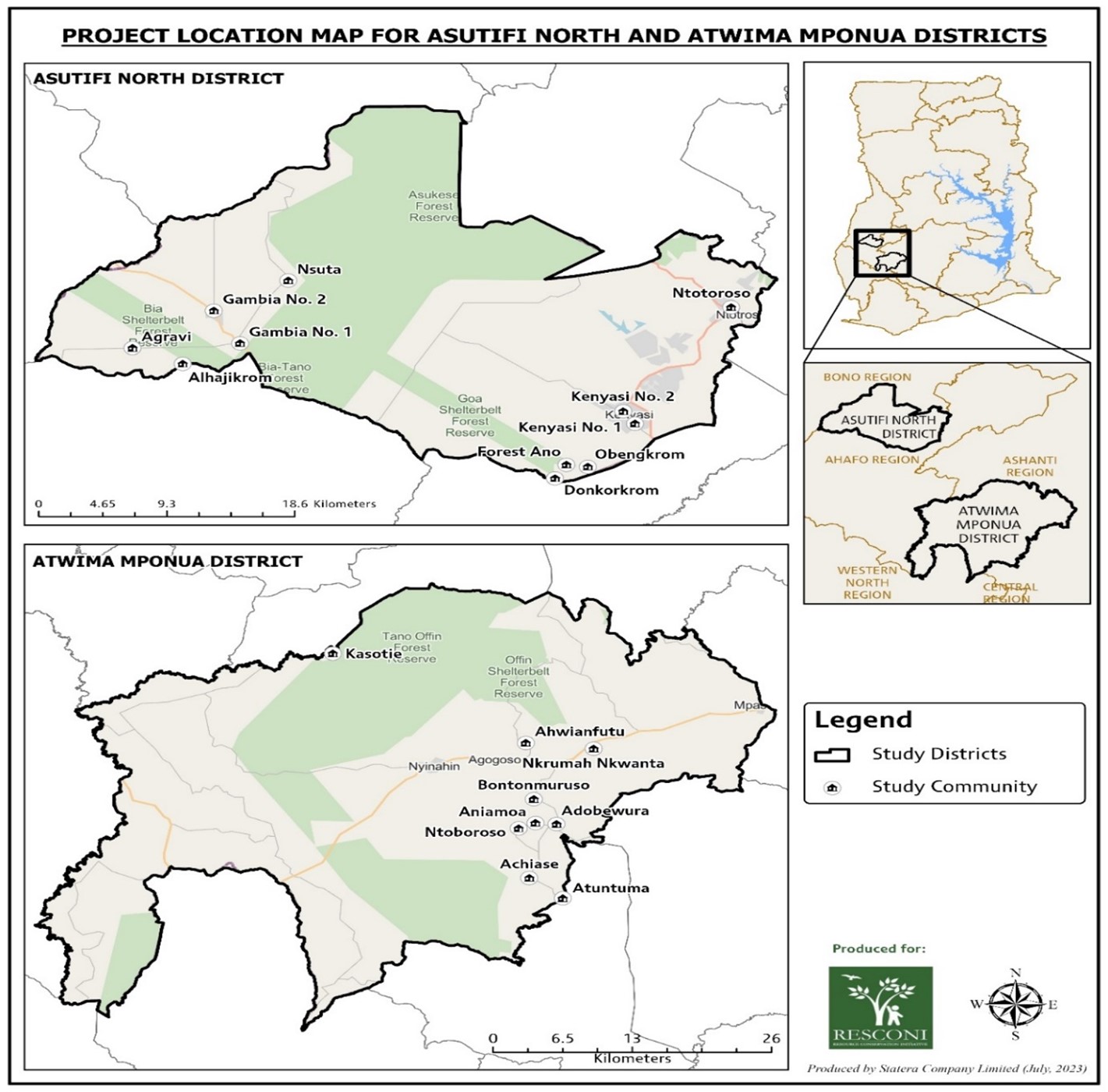

The case study was undertaken in two (2) districts, namely: Atwima Mponua District (AMD) and Asutifi North District (AND) in the Ashanti and Ahafo Regions of Ghana respectively. The study sites are sensitive biodiversity hotspots in Ghana containing several threatened endemic and species of conservation concerns locally and internationally. The Atwima Mponua District harbours the Tano Offin Forest Reserve which is the fourth largest Globally Significant Biodiversity Area (GSBA) in Ghana with a land mass of 41,392 hectares. It is characterized by a good network of rivers and streams with notable ones being Offin and Tano Rivers. The water bodies of this project region have been seriously polluted and contaminated as a result of mining and this is prominent at Ntroboso, Bontumumso, Aniamoa and Achiase. It has been earmarked for bauxite mining activities under the Ghana Integrated Aluminium Development Corporation (GIADEC) as a result of the huge bauxite deposits. Atwima Mponua District is also noted for agricultural commodity production such as cocoa and its production activities have been affected by both legal and illegal mining operations.

The study sites also have good edaphic conditions that support food crop production and agro-commodity cash crops especially cocoa in addition to rich mineral resources with gold being the most prominent. These favourable conditions have led to heightened illegal mining and unsustainable forest exploitation activities with negative impacts on the environment and destruction of the biodiversity resources of the study areas. The Asutifi North District is situated in the South Western part of the Ahafo Region. It harbours the Goa Shelterbelt, Asukese, Bia Shelterbelt and Bonkoni Forest Reserves. These forest reserves are underlaid by the Birimain and Dahomeyan rock formations which are potential sources of minerals such as granites, clay, sand, gold and diamond deposits. It covers large areas of forest reserves and mining concession for Newmont Ghana Gold Limited (NGGL) and extensive cocoa farmlands. The destruction of water bodies, forest and farmlands as a result of mineral extraction is prominent in Kenyasi, Ntotroso, Gyedu and Wamahinso. The basic characteristics and locations of the study areas are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1 respectively.

Table 1: Basic characteristics of the study areas (Source: RESCONI, 2023)

Table 2: List of Project Stakeholders (Source: RESCONI, 2023)

2.2 Data Collection

The study team adopted a concurrent mixed-methodological approach for data collection and analysis due to complexity of issues within the landscape utilizing both quantitative and qualitative tools. The sources of data include both primary and secondary with the latter collected through scientific, technical, and administrative reports, and publications from Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDA’s), journals and national dailies. The primary data was collected using questionnaire administration, key informant interviews and field observation methods.

For the questionnaire administration, a non-probability purposive sampling technique was used to select twenty (20) communities for the studies. In all, eleven (11) communities and nine (9) communities were selected for Asutifi North and Atwima Mponua Districts respectively. Simple random sampling technique was used to select target respondents at the community level for the study. The study targeted a total of to five hundred and twenty-eight (528) respondents which were proportionally distributed of which two hundred and ninety-four (294) respondents were from the Asutifi North District (AND) and two hundred and thirty-four (234) respondents from the Atwima Mponua District (AMD). The sample size was based on a 95% confidence level and an error margin of 5%. The targeted respondents were farmers mainly in cocoa production and miners involved in illegal mining activities.

The key informant interviews targeted about 55 representatives of key stakeholder institutions in the study area who have the mandate, power and interest in natural resource management and governance issues. These respondents could directly or indirectly influence the outcomes and impacts of the study and were purposively sampled and included representatives from government institutions, the private sector, civil society, traditional authorities and the communities. The field observation methods included the use of Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis and drone coverage to determine the land use and land cover of the study sites and also take real-time digital photographs to support the observation sessions. The data collection tool for the questionnaire survey was the KoboCollect platform. It was administered to the respondents by reading the questions from the screen of the Android tablets on which the KoboCollect application has been installed and entering the answers. The KoboCollect platform collected additional geo-data and photographs from participants in the study.

2.3 Data Analysis

Descriptive statistical tools such as frequencies and percentages were used to analyse nominal and ordinal variables that were quantitative in nature. On the other hand, continuous and discrete variables such as age, income, amongst others, were analysed using percentiles.

2.4 Ethical Consideration, Confidentiality, Validity and Reliability

The research team recognizes and respects the rights of the study participants for which reason participants expressed consent before the commencement of the interview. The purpose of the development research was adequately explained to the participants. Furthermore, participation in the study was voluntary, and participants were able to opt out at any time. To maintain anonymity, names, and other personal details of the study respondents at the community level were not captured as each respondent per the KoboCollect Toolbox was assigned a unique code for ease of reference.

With respect to data validity, the quality of both the primary and secondary data was high, the non-probability purposive sampling technique was appropriate for the development of a research of this nature. More so, the fieldwork was undertaken with support from the District Assemblies in reaching out to the targeted stakeholders within each district and included active participation of youth and women in the study. Please refer to Plate 1: A Picture for the Stakeholder Validation Workshop for Atwima Mponua District Assembly

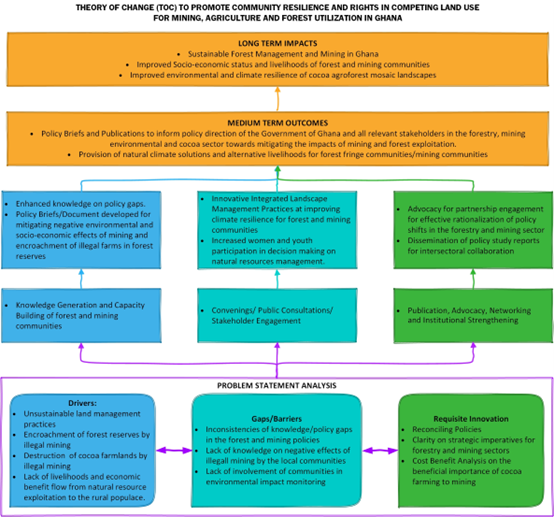

In terms of data reliability, the research team was well trained by the research lead and each of the research officers had a hands-on-experience before the actual field data collection. Each of the Android tablets were coded with unique identity for each of the researchers to capture, enter and upload data electronically. The KoboCollect has its own analyser, which uses extended excel capabilities toolkits to leverage the data format for proper analysis. This minimized the data transformation process, streamlined the data cleaning, and significantly increased precision and accuracy during data analysis. The concurrent mixed methodological approach adopted for the study is consistent with best practices. During interview and questionnaire administration, leading questions were deliberately avoided to prevent any bias from the research team. Additionally, the choice of data collection and analysis were guided and also based on the Theory of Change (ToC) of the project (Figure 2).

3. Results

3.1 Demographic and Socio-economic Characteristics of Respondents

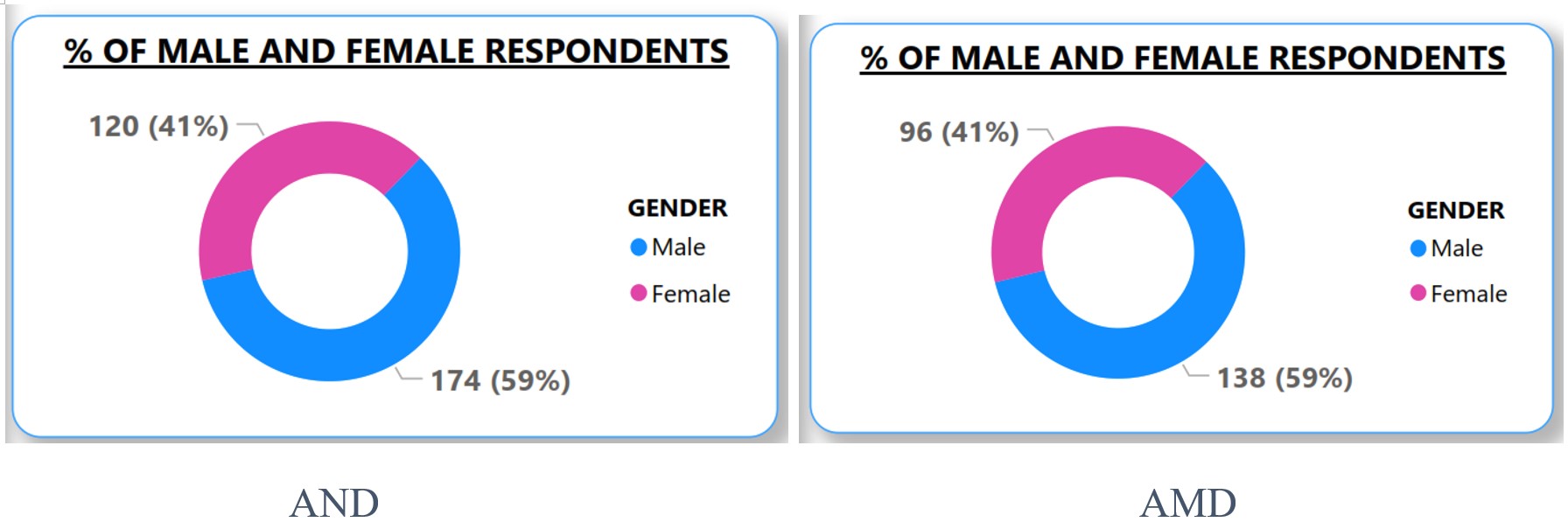

The demographic distribution of respondents varies across the study districts with respect to age, gender and nativity and occupation. The gender distribution of respondents across the study districts showed a similar distribution as AND and AMD both had 41% of respondents identified as females with 59% as males (Figure 3). Indicatively, male respondents formed a higher percentage relative to females, epitomizing the domination of males in farming and mining in AND and AMD. The significant proportion of females (41%) was a conscious effort to improve gender involvement and participation in the research process. This is consistent with the purposeful intention of RESCONI to ensure gender diversity and social inclusion in respect of women that ultimately creates more equitable cocoa farming communities. Moreso, this increased women participation is expected to drive transformative impacts as a result of women’s increased participation in decision making on natural resources management at the community level.

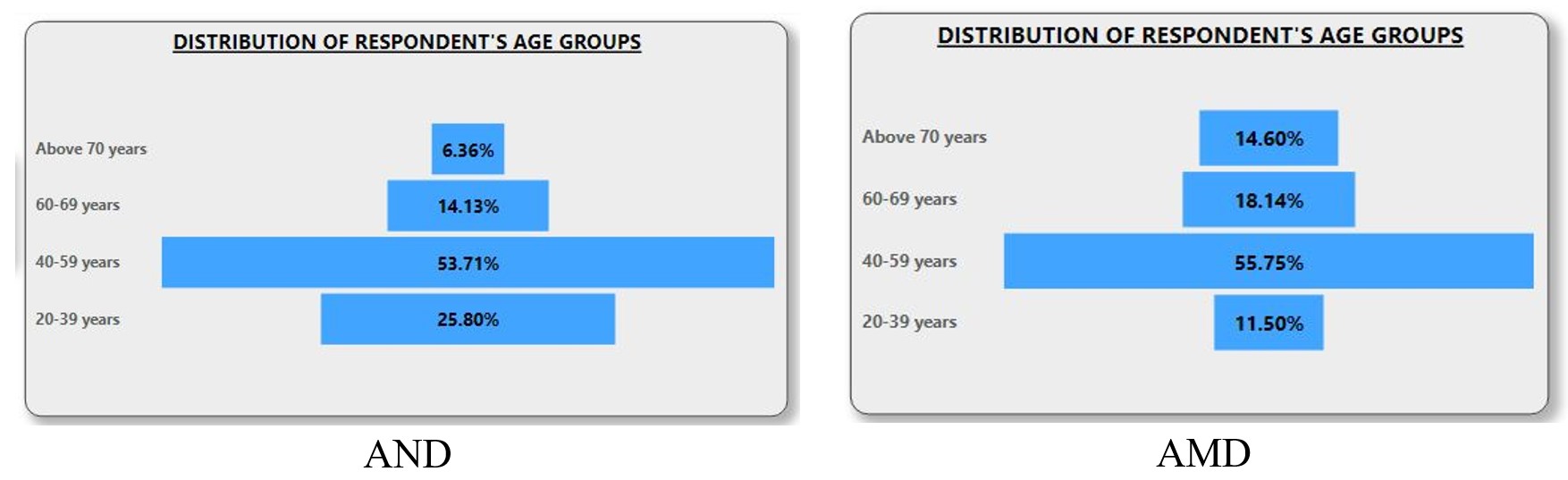

The age pyramid shown indicates some similarities but unique differences in the age distribution among the respondents in the study districts. For instance, AND and AMD showed a higher percentage of respondents within the 40-59 age group with AND having 53.71% and AMD having 55.75% and the other age groups forming the minority (Figure 4). This indicates an ageing farming population in the study districts. The second highest age cohort which represents youthful population (20-39 years) for AND and AMD are 25.80% and 11.5% respectively. This clearly shows the limited involvement of the youth in farming and agricultural related activities.

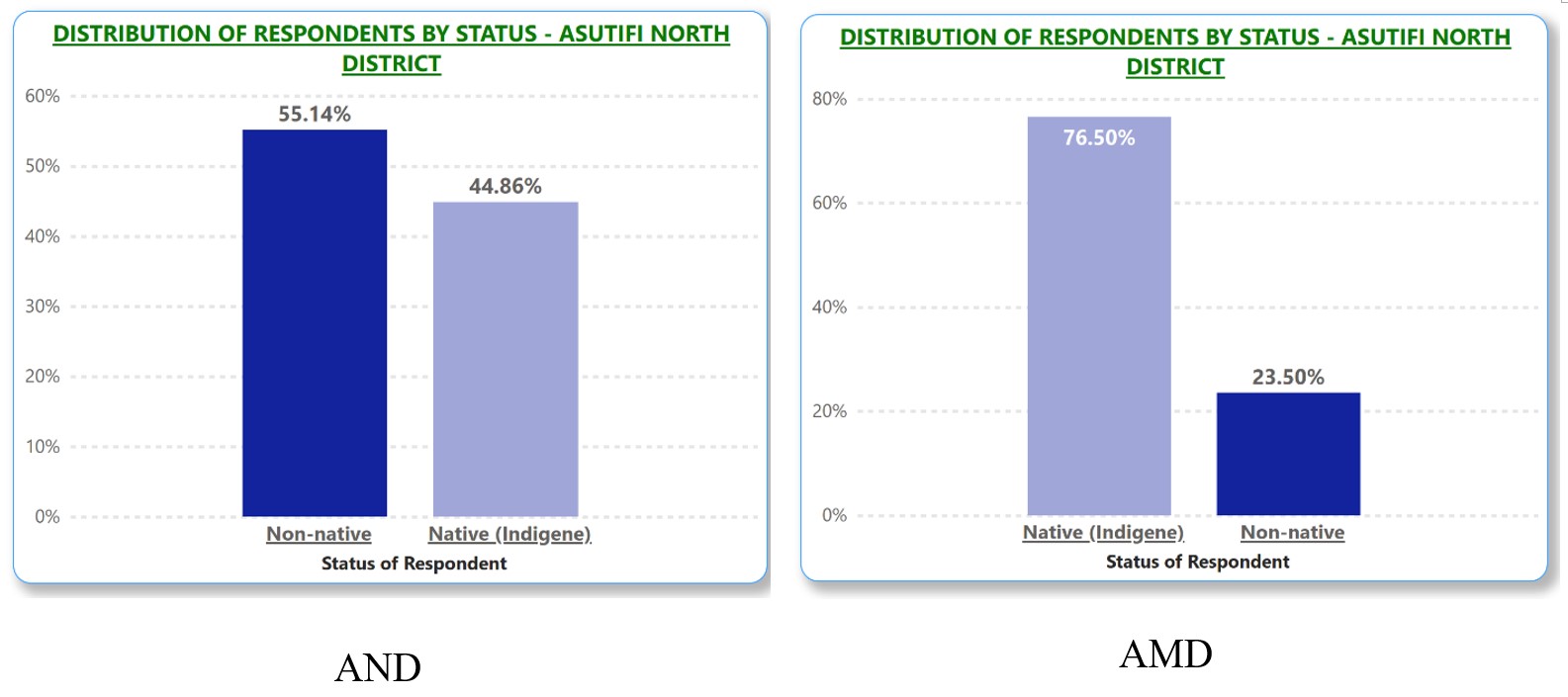

The study revealed that more than half (55.14%) of respondents in AND are non-natives with 44.86% being natives (indigenes) as depicted in Figure 5. Conversely, most of the respondents from AMD are natives (76.49%) with only 23.5% being non-natives. The high migration numbers of migrants in AND is driven mostly by good edaphic conditions and mineral-rich resources of the area as well as the ongoing mining activities of Newmont Ghana Gold Limited (NGGL) in the landscape.

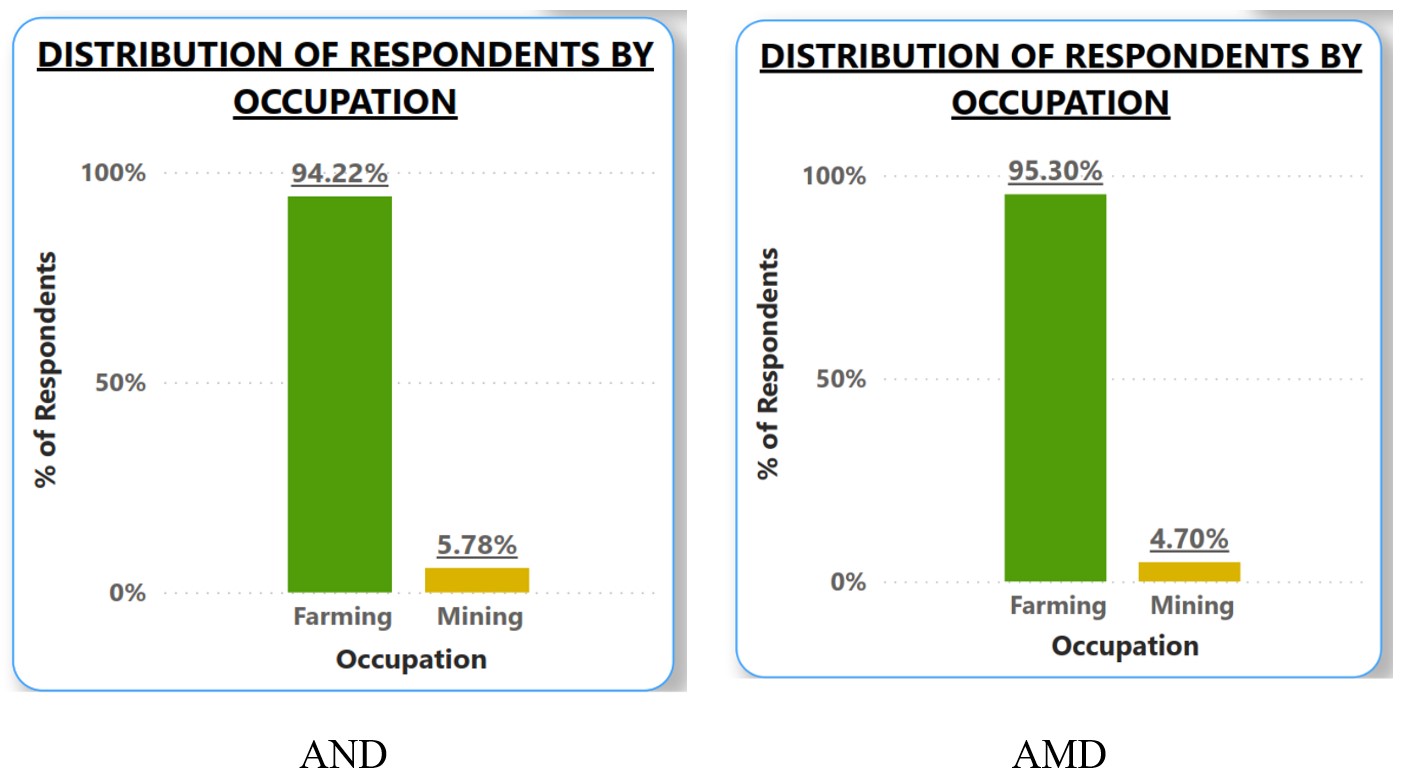

In terms of farming and mining households, there is a similarity in the distribution of respondents. In all the study districts, a significant proportion of the respondents (over 90%) were from farming households (94.22% for AND 95.30% for AMD) while less than 6% (5.78% for AND and 4.7% for AMD) were from mining households (Figure 6). This is consistent with the district level statistics which allude to farming as the dominant economic activity in the study districts. For instance, the 2021 Population and Housing Census – District Analytical Report for Asutifi North reports that as high as 66.10% of households engaged in agriculture.

3.2 Land Cover and Land Use Change

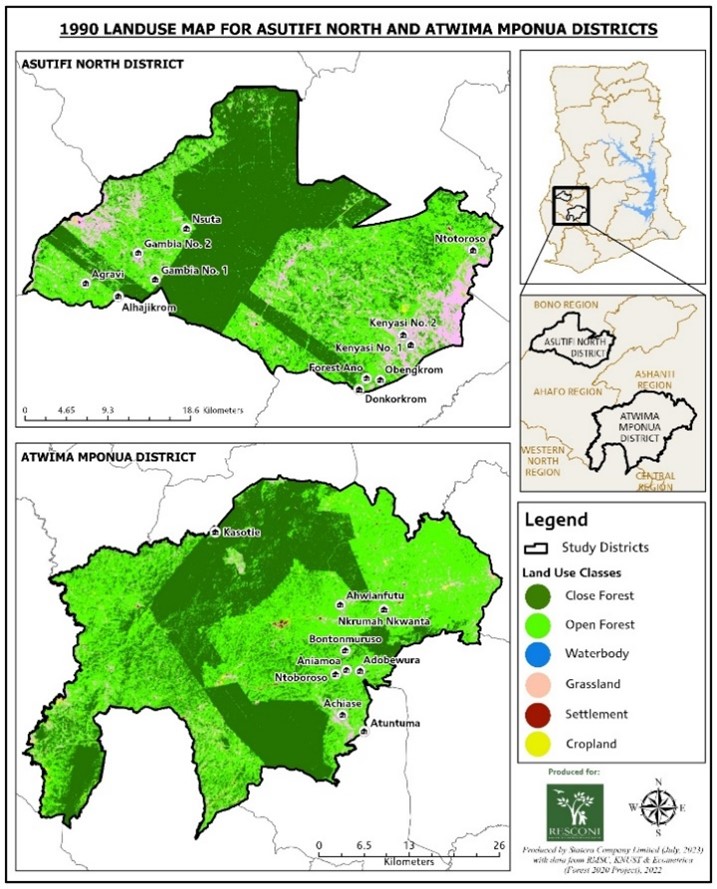

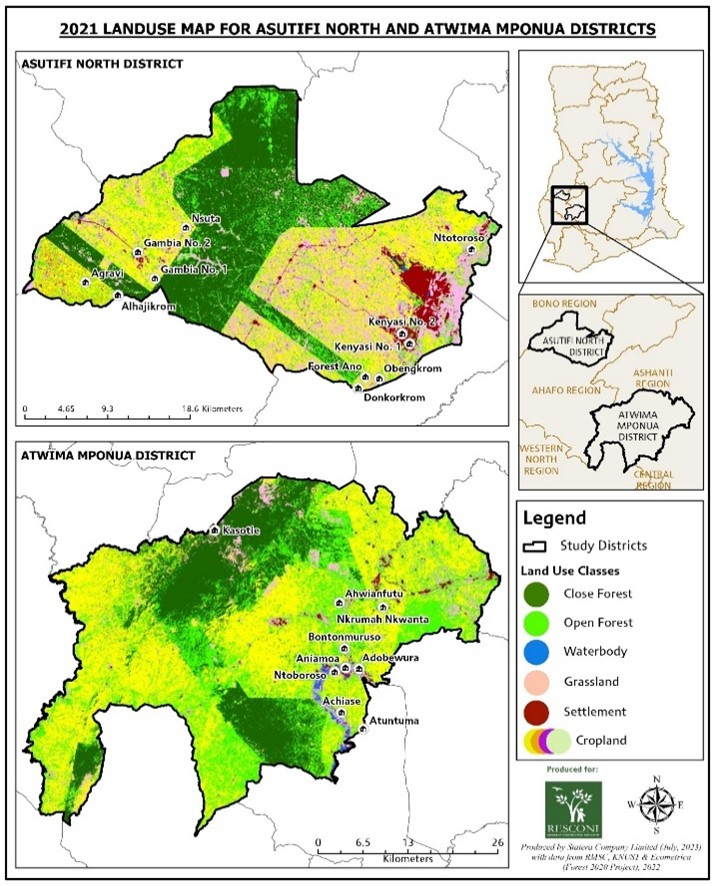

The dwindling forest cover has been confirmed through a 30-year land cover change analysis between 1990 and 2021 (Figure 7). The study revealed that there has been a 34.22% decline in closed forests and a 59.36% decline in open forests within AND. Similarly, closed forests within AMD have reduced by 48.44%, while open forests have reduced by 42.59%. The trajectory of forest cover decline leaves much worry and may indicate a failure of management and impacts from programmes and project interventions aimed at arresting deforestation and forest degradation. According to the information gathered from the District and Regional Forestry Mangers of the Forest Services Division (FSD), illegal logging is the leading cause of forest cover decline within forest reserves in each of the study sites ( AND and AMD). This is as a result of the fact that there are several illegal operators in both Districts who operate illegally to harvest timber trees from the forest reserves and/or outside forest reserves with impunity. Additionally, illegal mining was also identified as the second leading cause of deforestation and forest degradation. According to Arthur-Mensah (2023), illegal mining is rife affecting about thirty-four (34) major forest reserves.

3.3 Cocoa Farming and Other Food Crops Production as the Dominant Livelihood Activity

The dominant land use for both Districts was farming. More than 90% of the respondents indicated that cocoa production and farming activities were the main use of the land. In specific terms, cocoa production was ranked as the second most important farming crop after cassava for both districts scoring 22.60% and 31.85% respectively for AND and AMD respectively. The cocoa farmers were smallholders with smaller farm sizes and comparatively low incomes since the productivity of cocoa farms per hectare was well below the required yield range of 1,000 kg/ha – 1,900 kg/ha (Van Vliet et al, 2021).

3.4 Drivers of deforestation and forest degradation

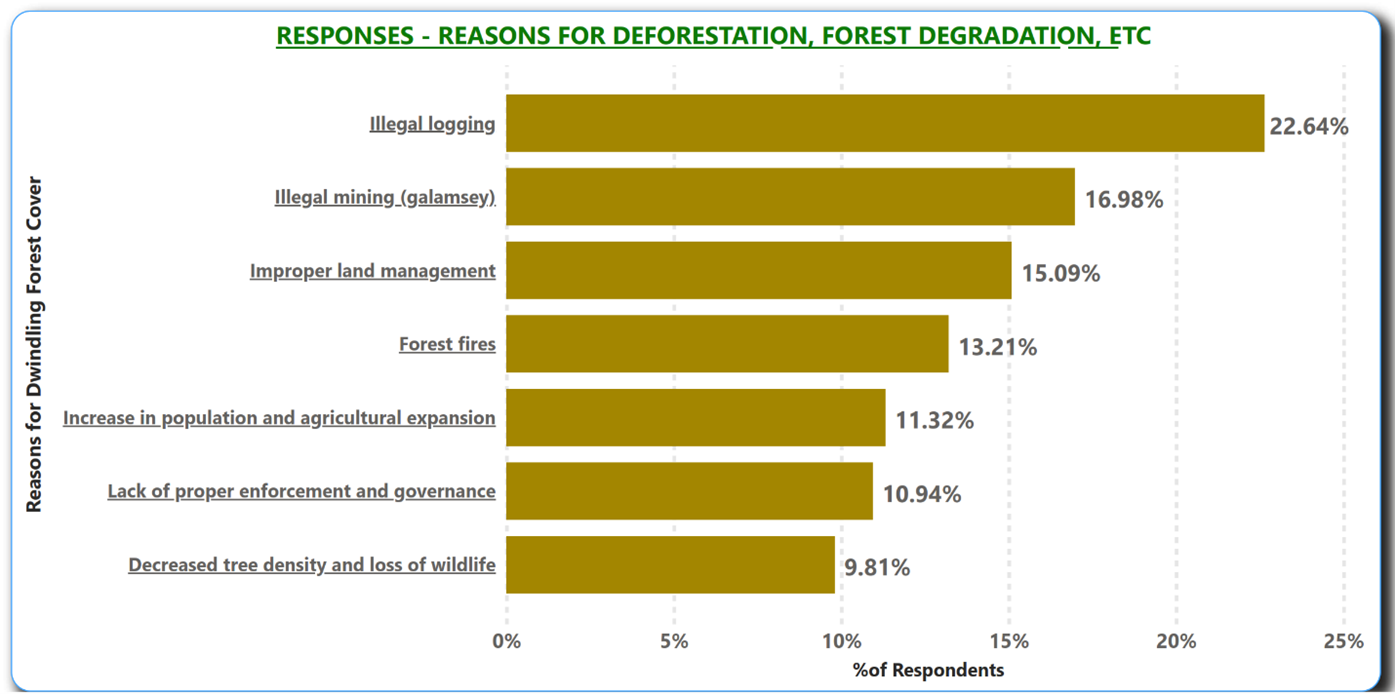

Illegal logging has been reported by respondents in the study districts as the most dominant (22.64%) driver of deforestation and forest degradation in the project areas (Figure 8). About 16.98% of respondents (from AND and AMD) believe that illegal mining (galamsey) is the second most prevalent reason for the dwindling forest cover. Other reasons mentioned by respondents include improper land management (15.09%), forest fires (13.21%), increase in population and agricultural expansion (11.32%) as well as lack of proper enforcement and governance (10.94%). Decreased tree density and loss of wildlife was mentioned by only 9.81% of respondents as the reason for deforestation and forest degradation.

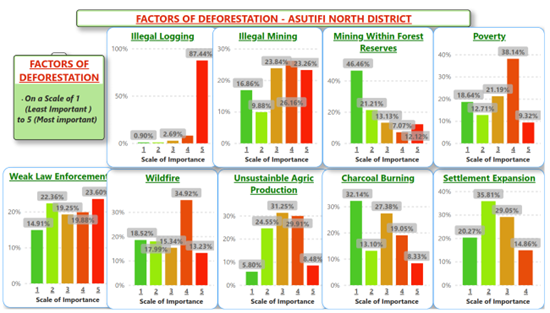

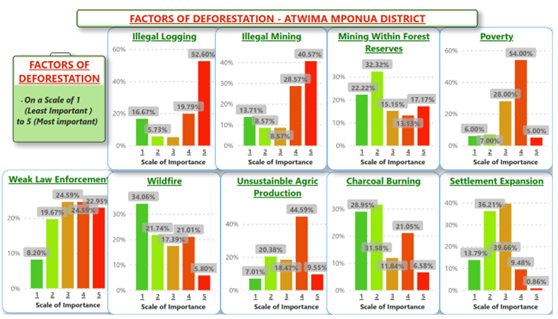

In ranking the importance of the factors that account for deforestation in AND (Figure 9), 87.44% of respondents confirmed illegal logging as the most important contributing factor, followed by weak law enforcement (23.60%) and illegal mining (23.26%). Mining within forest reserves was ranked as the least important factor accounting for dwindling forest cover (46.46%) followed by charcoal production (32.14%) and settlement expansion (20.27%). Other factors include poverty, wildfires as well as unsustainable agriculture production.

Responses from respondents in AMD (Figure 10) confirm ‘illegal logging’ as the most important factor contributing to deforestation in AMD, followed by ‘illegal mining’ (40.57%) and ‘weak law enforcement’ (22.95%). ‘Poverty and unsustainable agriculture production’ were considered to be of significant importance in contributing to deforestation by respondents (54% and 44.59% respectively). ‘Wildfires’ (34.06%) and ‘charcoal production’ (28.95%) were considered as the least important factors accounting for deforestation in AMD. Other factors mentioned include ‘expansion of settlements/ built up areas’ and ‘mining within forest reserves.’

From the foregone, unsustainable logging practices, agricultural expansion, and fuelwood collection contribute to deforestation and forest degradation in the study districts. This has led to the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services, and negatively affects the livelihoods of communities. It is worth mentioning that, if this trajectory remains unchecked, it could cause a drastic decline in the total tonnage of cocoa produced in these project districts. It is therefore important that urgent efforts be made, using collaborative inter-sectoral strategies, institutional strengthening, harmonization of the relevant policies, and legal enforcement to mitigate the negative impacts of unsustainable forest exploitation and mining on cocoa production in the communities of the project districts.

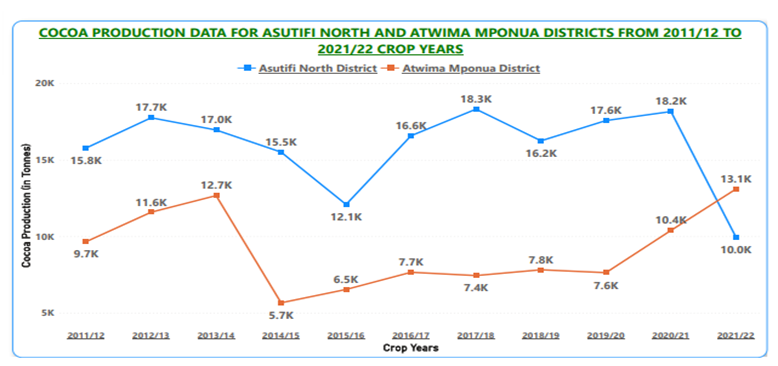

3.5 Cocoa Production and Livelihood Nexus

The cocoa production-livelihood nexus refers to the significant role that cocoa farming plays in the livelihoods (income, employment and sustenance) of many households in the study communities. The Figure 11 shows the cocoa production data for 2011/12 to 2021/22, as received from the Ghana Cocoa Board for the two (2) project districts. It was observed from the trend analysis that cocoa production has declined sharply from 2011/12 annual production of 15,500 tonnes to 10,000 tonnes in 2020/21 for AND (Figure 11). From the cocoa production data for Nyinahini Cocoa District, Ashanti Region and Kasapin Cocoa District, Ahafo Region, from 2011/12 to 2021/22 Crop Years, the peak production stood at 18,311.06 tonnes for 2017/18 for Kasapin with jurisdictional coverage for Asutifi North District and this has been followed by a consistently low production levels year on year that amounted to 9,956.38 tonnes for 2021/22. This situation is attributable to the increasing levels of mining activities. On the contrary the production levels for AMD has progressively increased year on year since 2019.

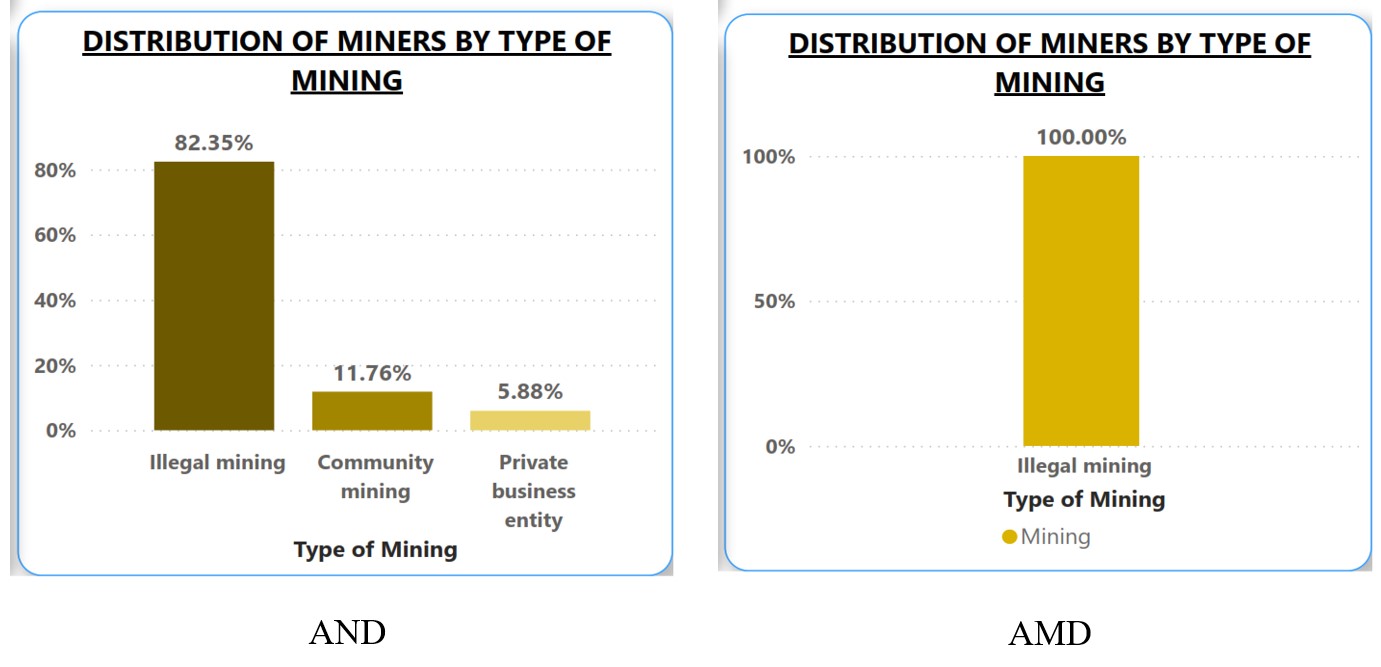

3.6 Mining and Livelihood Nexus

The study districts are known for their rich mineral resources, including gold and bauxite, thus mining plays a significant role in the economy of the study districts. As shown in Figure 12, there are three (3) distinct types of mining systems in AND compared to AMD. In AND, illegal mining is carried out by an estimated 82.35% of respondents who are unregulated miners popularly called galamseyers. Another category is the community mining scheme that is regulated but the lack of proper supervision has made most of their operations to mimic that of illegal mining activities and is being undertaken by 11.76% of the respondents. The remaining 5.88% of the respondents are miners who are engaged in private businesses purposely incorporated for mining and related activities such as sand wining. In contrast, all respondents in AMD were engaged in illegal mining.

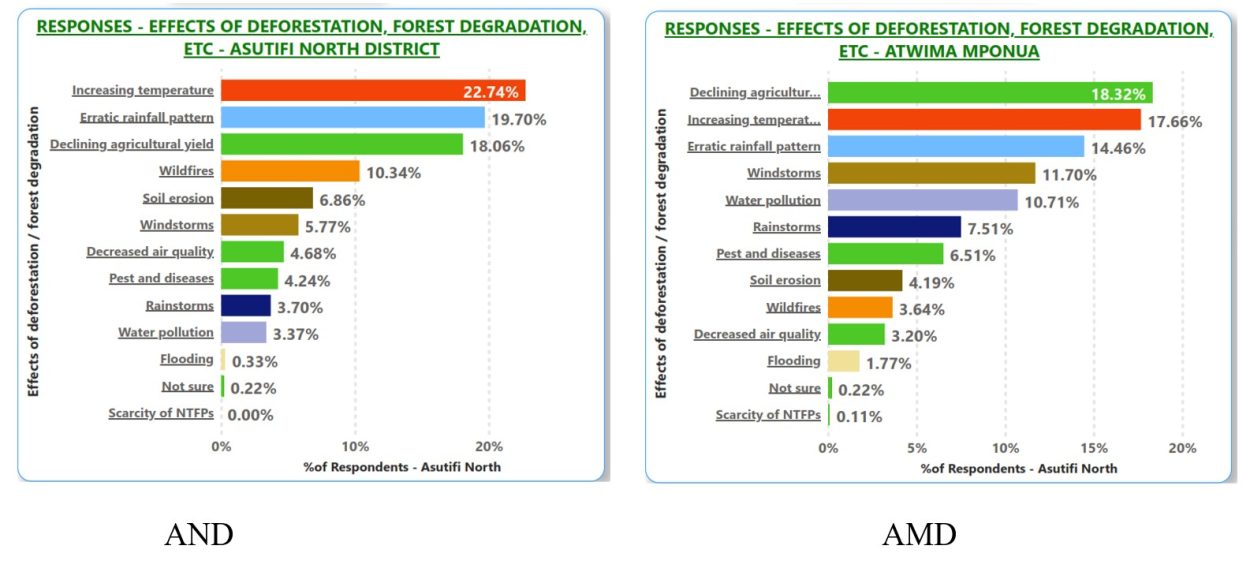

3.7 Perceived Effects of Deforestation and Forest Degradation

The perception of respondents about the effects of deforestation and forest degradation varies across the study districts (Figure 13). The respondents in AND consider increasing temperature (22.74%), erratic rainfall pattern (19.70%), declining agricultural yield (18.06%) and wildfires (10.34%) as the most dominant perceived effects of deforestation and forest degradation. Other perceived effects mentioned by respondents in AND include soil erosion (6.86%), windstorms (5.77%), decrease in air quality (4.68%), pest and diseases (4.24%), rainstorms (3.70%), water pollution (3.37%), flooding (0.33%), not sure (0.22%) and scarcity of non-timber forest products (0.00%). Meanwhile, respondents in AMD perceive declining agricultural yield (18.32%), increasing temperature (17.66%), erratic rainfall pattern (14.46%), windstorms (11.70%) and water pollution (10.71%) as the dominant effects of deforestation and forest degradation. Other factors perceived by respondents in AMD as the effects of deforestation and forest degradation include rainstorms (7.51%), pests and diseases (6.51%), soil erosion (4.19%), wildfires (3.64%), decreased air quality (3.20%), flooding (1.77%), not sure (0.22%) and scarcity of non-timber forest products (0.11%).

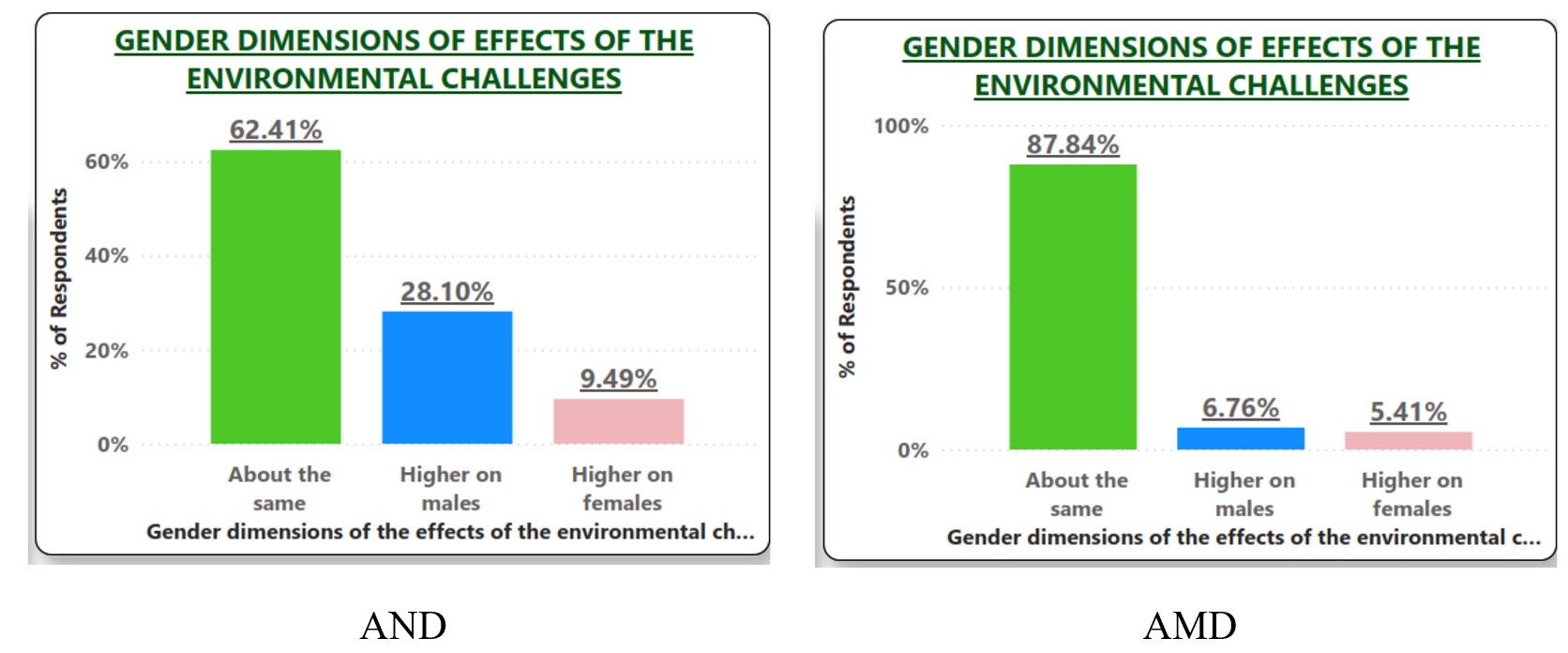

The gendered effects of deforestation and forest degradation among respondents denote a perception of an equal effect on both males and females. About 62.41% of respondents in AND believe that the effect of deforestation and forest degradation on both males and females are the same with 87.84% of respondents from AMD sharing the same view (Figure 14). A slightly higher proportion of respondents in AND (28.10%) believe males are most affected by the effects of deforestation and forest degradation relative to the respondents from AMD (6.76%).

3.8 Awareness of Sustainability Initiatives and Interventions

There are on-going sustainability initiatives and interventions such as the Ghana Cocoa Forest REDD+ Programme (GCFRP) that seeks to promote biodiversity conservation, emission reduction and carbon stock enhancement strategies through improved forest management, agroforestry, afforestation, reforestation and restoration. Additionally, there are also community-based forest management initiatives that involve local communities in forest conservation and its benefit-sharing being implemented in the study districts most notably Community Resource Management Areas (CREMAs) and Hotspot Intervention Areas (HIAs) approach under the Cocoa Forest Initiative which are on-going in the project areas. Therefore, the level of awareness of respondents about these sustainability initiatives being implemented to address deforestation, forest degradation and other environmental challenges were assessed (Figure 15).

In AND, respondents indicated their awareness of initiatives aimed at addressing sustainability challenges as Yes (32%), and No (68%). Meanwhile, the level of awareness in AMD was relatively low with only 17% being aware of initiatives to address environmental challenges with 83% not aware of such initiatives. This necessitates intensified public awareness and community education on sustainability initiatives within the study communities to reduce deforestation, forest degradation and other environmental challenges to enhance the socio-ecological health of the landscape.

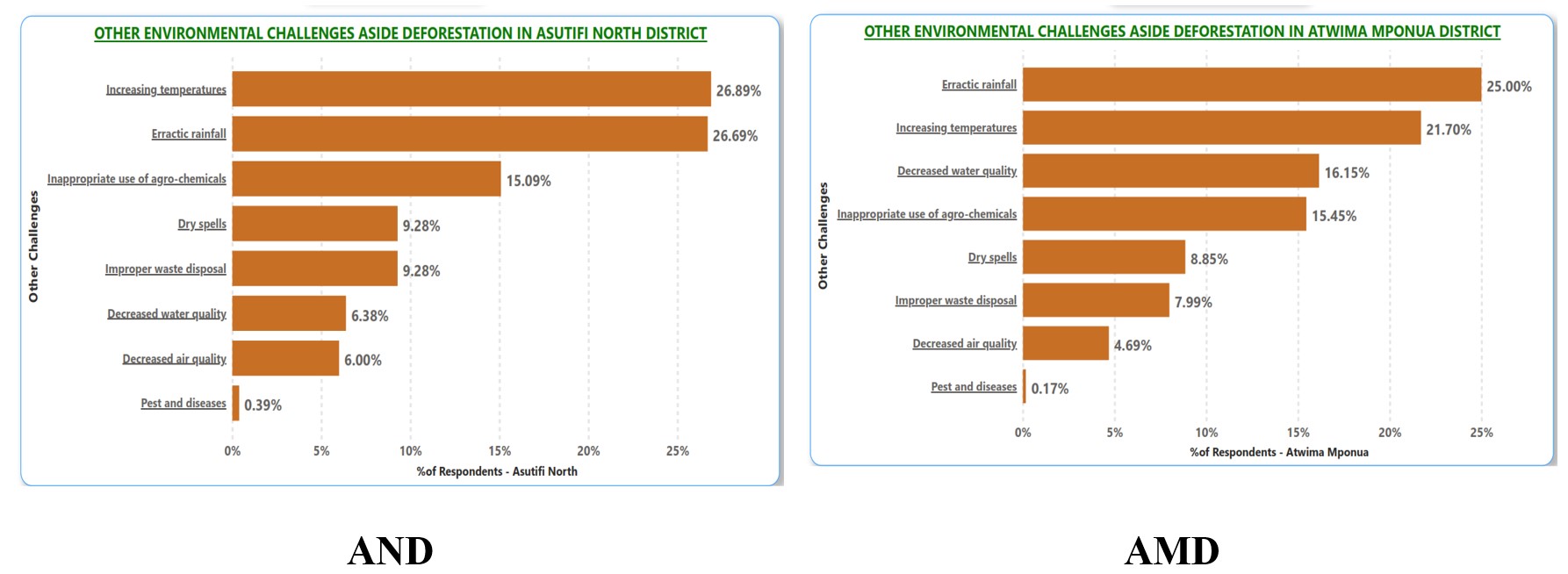

3.8 Other Environmental Challenges in the Study Districts

Information on other environmental challenges being experienced by respondents besides deforestation and forest degradation were also collected (Figure 16). Increasing temperatures and erratic rainfall were the highest perceived environmental challenges mentioned by respondents in both AND and AMD. About 26.89% of respondents in AND believe increasing temperatures are the most prevalent environmental challenge followed by erratic rainfall (26.69%), inappropriate use of agro-chemicals (15.09%), dry spells (9.28%), improper waste disposal (9.28%), decreased water quality (6.38%), decreased air quality (6%) as well as pest and diseases (0.39%). The environmental challenges perceived by respondents from AMD include erratic rainfall (25%), increasing temperature (21.70%), decreased water quality (16.15%), inappropriate use of agro-chemicals (15.45%), dry spells (8.85%), improper waste disposal (7.99%), decreased air quality (4.69%) as well as pest and diseases (0.17%). Generally, decreased air quality as well as pest and diseases were perceived as the least environmental challenges in both study districts.

4. Discussions and Lessons Learnt

4.1 Discussions

The socio-economic factors analysed in the study included gender, age, occupation and nativity status of the respondents. The respondents epitomize the domination of males in farming and mining activities in the study districts. Traditionally, farming activities are mostly preserved for males who have the manpower and the resources to effectively manage the farming and mining ventures with the women playing supporting roles on these ventures due to their domestic roles within the family set up. According to Appiah (2009), the study sites being typical traditional communities and agrarian economies are expected to exhibit male dominance in the livelihoods of the communities.

The gender effects of deforestation and forest degradation from respondents denotes a perception of an equal effect on both males and females. About 62.41% of respondents in AND believe that the effect of deforestation and forest degradation on males and females are the same with 87.84% of respondents from AMD sharing the same view. A slightly higher proportion of respondents in AND (28.10%) believe males are most affected by the effects of deforestation and forest degradation relative to the respondents from AMD (6.76%).

With respect to age, a higher percentage score (i.e. more than 50% for respondents within and over the 40-59 age group) indicates an aging farming population in the study districts. The study further revealed the limited involvement of the youth (between 20-39 years) in farming and agricultural activities for both study sites and this confirms the growing concern of dwindling interest of the youth in farming and agricultural-related activities in the study districts and the country as whole. Additionally, within the current rural economic settings, studies have shown that the youth are mostly attracted to quick and high remuneration activities especially mining in the communities where farming and mining constitute competing interest for livelihoods (World Bank Group 2018; Lamptey & Ofori-Danson, 2014; Weiss & Börsch-Supan (2011).

On nativity characteristics, there was observed general trend of higher migrant status (an average of about 65% over natives) in the study districts, which is an indication of the study sites’ attractiveness to migrants. Recent studies have revealed that cocoa production and mining attract migration to areas with good edaphic and mineral resources of which the study communities are no exception. Additionally, there was noticeable variation in migrant status in the study districts with more migrants to AND than AMD) and this could be partly explained by levels of respondents engaged in mining and the diversity of mining distribution types in each study district. The study revealed that AND had more people in mining and also diversity in mining distribution than AMD in a ratio of 3:1. In as much as both farming especially cocoa cultivation and mining attract migrants, some studies have shown that mining has more pull factor for migration than cocoa due to its high and short relative financial compensation that it offers to its labour (RMSC, 2016; Conservation Alliance, 2021). This probably explains why percentage migration to AND was more than that of AMD.

The study clearly established the domination of agriculture (farming) as the preferred occupational choice within the study sites which is consistent with most rural economies in Ghana (Asutifi North District, 2017 & Atwima Mponua District 2017). However, increasing lack of interest of youth and shift of labour from agriculture to other sectors especially mining is very concerning for the long-term sustainability of the agriculture industry which has traditionally and consistently supported the rural economy of the study sites. Therefore, any reversal of this trend will require concurrent efforts of making illegal mining unattractive especially to the youth. This could be done through education and awareness creation on the dangers of illegal mining to the socio-ecological health of the landscape; and strict enforcement of mining laws whilst providing incentives such as capacity building; inputs support/subsidy schemes, increasing farm productivity and ultimately enhancing income generation from agriculture and developing the capacity of the youth to engage in other alternative livelihoods.

Farming-livelihood nexus plays a significant role in the economy and the livelihoods of the majority of the population in the study districts. According to the Ghana Statistical Service (2021), agriculture remains the backbone of the local economy, employing not less than 60% of the study districts’ workforce and contributing to food security, rural development, and poverty reduction. A significant proportion of the respondents (over 90%) were involved in farming in the project study sites. This confirms the District Analytical Reports and the well-established notion that farming is the dominant economic activity in the study districts. Additionally, the study further revealed that farming is characterized by smallholder farmers who produce mostly for subsistence with few commercial purposes using simple farming methods. Studies have shown farming is very typical livelihood component of the rural economy which provides employment and income generation; food security and nutrition and when properly harnessed could ensure climate resilience and adaptation; sustainable natural resource management; gender and social inclusion to enhance the overall development of the rural economy of the study sites.

The study districts are of utmost interest as it is being subjected to the impacts of both legal and illegal mining and this invariably exerts negative impacts that are causing cocoa production levels to decline in these areas (Allan& Fatawu, 2014; Guenther, 2018). The number respondents engaged in mining in the project districts may be perceived as relatively low but mining activities cause irreparable damage to the ecosystem and also contributes significantly to competing land use that are very harmful to cocoa production. However, despite the significant contributions from mining, forestry and agriculture to the communities’ socio-economic development, the study sites are faced with the risk of an ecological destruction due to the high levels of environmentally unfriendly human activities (such as illegal mining, illegal logging/lumbering and unsustainable farming such as within riverine buffer zones) that cumulatively poses severe environmental problems, destruction of the biodiversity resources, environmental services and livelihood challenges to the local communities.

According to recent studies and reports, mining constitutes one of the most direct and immediate threat to cocoa growing communities in Ghana (Lawal & Emaku, 2007; Tuholske et al, 2020). There is evidence that suggests that the upsurge in illegal mining activities has led to increased damaging consequences (such as forest resource degradation, soil nutrient depletion, wildlife habitat destruction, pollution of water bodies, and reduction in quality and threat to human health) according to Emmanuel et al.(2018). Moreso, a study by Owusu et al. (2016) revealed that illegal small-scale gold mining operations along riverbanks has led to pollution of water bodies, making them unsuitable for both domestic and agriculture use and that it poses threats to biodiversity and the natural environment if not undertaken sustainably. It is therefore important that urgent efforts are needed to regulate and mitigate these negative impacts of mining through collaborative inter-sectoral and institutional strengthening, harmonization of the relevant and applicable environmental policies and laws within a strict legal enforcement regime.

4.2 Lessons Learnt

The major lessons from the study were as follows:

- The competing interest from mining, agriculture and forest utilization should be addressed holistically within the context of a multi-stakeholder approach. This will ensure that the local governments, relevant regulatory agencies (FSD, EPA, COCOBOB, MINCOM, etc.), the Traditional Authorities, businesses/private sector, communities and all other interested stakeholders (local and international NGOs) involved and interested in the management and sustainable utilization of the natural resources are equipped to contribute effectively. This will ensure sustainable management and enhanced protection of the socio-ecological production landscapes.

- There is the need for sustainable best practices, environmental protection measures and community involvement in the planning and decision-making processes. The government, together with all stakeholders need to review and implement its policies, and regulations to ensure environmental conservation, responsible resource utilization, effective forest law enforcement and socio-economic development of the forest and mining communities.

- According to the study, forest and ecosystem restoration plays an important role in biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services that are vital for the survival of a wide range of both flora and fauna and also support the health and productivity of forest landscapes. Furthermore, forest and ecosystem restoration activities provide life-supporting roles for forest fringe communities and the local populace who depend on forest resources and biodiversity for livelihoods.

- Considering the economic benefits vis-à-vis potential threats of mining and forest utilization, there is now an increasing awareness for cross-sectoral links for sustainable exploitation of the countries’ natural resources whilst minimizing the deleterious environmental and social impacts of illegal mining and timber logging on the national economy. Consequently, several programmes, including the Ghana Forest Investment Program (GFIP) (working with cocoa farmers and communities to rehabilitate and protect the forest reserves), have been implemented to stem the tides. Thus, it is evident that utilization of natural resources does not only require exploitation but also more importantly sustainability management, that ensures minimal adverse environmental effects (mitigating climate crisis), and ensuring optimal flow of benefits to the present and future generations.

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

The important summary findings of the study were as follows:

The trajectory of forest cover decline leaves much worry and may indicate a failure of management, programmes and initiatives aimed at arresting deforestation and forest degradation. The spatial evidence gathered reveals a dwindling forest cover. This has been confirmed through a 30-year land cover change analysis between 1990 and 2021. This was further confirmed through community survey by majority of the respondents who attested that the forest cover has dwindled over the past 30 years. It also revealed that though significant proportion of the community were farming households with very few from the mining households, the major threat to the sustainability of the environment and socio-economic development of the local communities was more attributable to mining than farming. The study further highlighted the urgent need to balance farming, mining and forest resources utilization in project districts that ensure sustainability, social inclusiveness and economic development.

The major recommendations from the study were as follows:

- A human and environmental centred approach with a gender focus should be adopted to address the threats from illegal forest exploitation and mining to safeguard the ecological integrity of the project landscapes. This invariably will result in improved cocoa production and the socio-economic wellbeing of the local communities including the women and youth.

- There should be sustained community education and public awareness about the dangers of unsustainable resource exploitation on the socio-ecological health and economic development of the project landscapes. Thus, the Traditional Authorities and community members must be empowered develop their leadership and adaptive management for improved resource governance.

- There is a broad array of stakeholders intrinsically linked to the search for effective solutions towards addressing the menace of illegal mining and unsustainable forest exploitation. To this end, the preferred coordination strategy should be a multi-stakeholder approach which allows several actors to work in concert and must be continuously and vigorously explored for effective implementation.

- There is the need to to promote sustainable farming practices through the adoption of agroforestry, good agricultural practices, agroecology principles, soil conservation techniques, integrated pest management, and the use of organic fertilizers as well as research and training on the use of pesticides. This will ensure the mitigation and avoidance of the negative health impacts of human activities on the biodiversity resources and health of the human population in the communities of the project districts.

Refrences

Allan, A. & Fatawu, N. A. (2014) Managing the Impacts of Mining on Ghana’s Water Resources from a Legal Perspective. JENRM, Vol. I, No. 3, 156-165.

Appiah, D. (2009). Personifying sustainable rural livelihoods in forest fringe communities in Ghana: A historic rhetoric? Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment, 7, 873–877. https://www.academia.edu/53213357/Personifying_sustainable_rural_livelihoods_in_forest_fringe_communities_in_Ghana_A_historic_rhetoric

Arthur-Mensah, G. (2023). 34 Major Forest in Ghana Significantly Impacted by Illegal Mining.

A Report by Ghana News Agency (GNA).

Asutifi North District (2017). Medium-Term National Development Plan, 2018-2021. Final Draft Report. ttps://www.ndpc.gov.gh/resource_and_publications/plans?page=4#

Atwima Mponua District (2017). Medium-Term National Development Framework 2018-2021. Final Draft Report. ttps://www.ndpc.gov.gh/resource_and_publications/plans?page=4#

Conservation Alliance (2021). Socio-economic Study Report. Prepared for Newmont

GoldCorp Ghana Limited (Unpublished).

Derkyi, M.; Ros-Tonen, M. A.; Kyereh, B.; Dietz, T. (2013). Emerging Forest Regimes and Livelihoods in the Tano Offin Forest Reserve, Ghana: Implications for Social Safeguards. Forest Policy and Economics 2013, 32, 49-56.

Emmanuel, A. Y.; Jerry, C. S.; Dzigbodi, D. A. (2018) Review of environmental and health impacts of mining in Ghana. Journal of Health and Pollution 8 (17), 43-52.

Ghana Statistical Service (2020). Annual Agriculture Production Statistics – January 2020.

Guenther, M. (2018). Local Effects of Artisanal Mining: Empirical Evidence from Ghana. Royal

Holloway College, University of London, Retrieved from https://delvedatabase.org/uploads/resources/Local-Effects-of-Artisanal-Mining-Empirical-Evidence-from-Ghana.pdf

Lamptey, A. M., & Ofori-Danson, P. K. (2014). Review of the Distribution of Waterbirds in Two Tropical Coastal Ramsar Lagoons in Ghana, West Africa. West African Journal of Applied Ecology, vol. 22(1), 77–91. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/wajae/article/view/108001

Lawal, J. O.; Emaku, L. (2007). Evaluation of the Effect of Climatic Changes on Cocoa Production in Nigeria: Cocoa Research Institute of Nigeria (CRIN) as a case study, African crop science conference proceedings, 2007; pp 423-426.

Nyabor, J., (2019). Akufo-Addo’s 2019 State of the Nation Address [Full Speech]. Citi Newsroom.

Owusu, P. A.; Asumadu-Sarkodie, S.; Ameyo, P. (2016) A Review of Ghana’s Water Resource Management and the Future Prospect. Cogent Engineering, 3 (1), 1164275.

Resource Management Support Centre (2016). Mapping of mining areas within and around Atewa Globally Significant Biodiversity Area. Report produced for A Rocha Ghana under the Atewa Living Waters Project.

Tuholske, C.; Andam, K.; Blekking, J.; Evans, T.; Caylor, K. (2020). Comparing Measures of Urban Food Security in Accra, Ghana. Food Security.12, 417-431.

Van Vliet, J.A, Slingerland, M.A, Waarts, Y.R & Giller, K.E (2021). A Living Income for Cocoa Producer in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, Volume 5

https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.732831

Vigneri, M.; Kolavalli, S. (2017). Growth through Pricing Policy: The case of cocoa in Ghana. Background paper for UNCTAD-FAO Commodities and Development Report.

Weiss, M., & Börsch-Supan, A. (2011). Productivity and age: Evidence from work teams at the assembly line. VfS Annual Conference 2011 (Frankfurt, Main): The Order of the World Economy – Lessons from the Crisis 48719, Verein für Socialpolitik / German Economic Association, viewed 6 July 2022. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/vfsc11/48719.html.

World Bank Group (2018). Third Ghana Economic Update: Agriculture as an Engine of Growth and Job Creation.