Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama: Revitalizing and passing on the rich and historical relationship between humans and nature in Arima to the next generation

19.01.2023

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

AEON Environmental Foundation

OTHER CONTRIBUTING ORGANIZATIONS

Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES),

The government of Minami-Shimabara City

DATE OF SUBMISSION

11/01/2023

REGION

Asia

COUNTRY

Japan

KEYWORDS

Multi-actor, mediator, landscape approach, universal forest use, history approach

AUTHORS

Yasuo Takahashi, IGES

Shigeharu Uchida, The government of Minamishimabara City

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Introduction

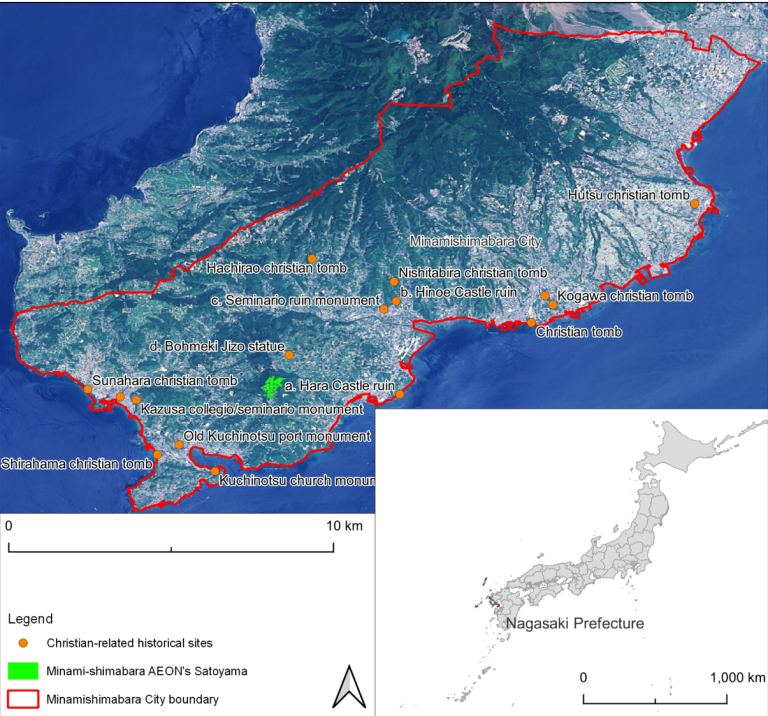

The 1637 Shimabara-Amakusa Rebellion occurred in the early Edo period of Japan. This was an uprising against harsh regime enforced in the Shimabara domain, including heavy taxation and the violent prohibition of Christianity. The rebels fought against the shogunate forces, but the uprising was suppressed and the rebels executed. The “Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama” is located on the top of a hill that stretches behind Hara Castle ruins, which marks the scene of the rebellion and has been designated as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site.

On the hill-top highland called Uehara, in Minami-Shimabara City, Nagasaki Prefecture where the Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama is located, there was a water source forest until the early 20th century that supplied water to the villages and terraced rice paddies at the foot of the mountain. The forest was converted to farmland by returning settlers after World War II. Subsequently, a large radio transmission station was constructed in 1978 on the land, which reportedly affected the water source at the base of the mountain. With the closure and removal of the station in 1999, a proposal was made to create a “citizens’ forest” to restore the forest and its ecosystem functions, such as water source recharge and protection against landslides. Thus, the Satoyama has gradually been restored through collaborative efforts by the local government and citizens, and new forms of the sustainable relationship between humans and nature are being sought that effectively use various ecosystem goods and services deriving from the restored Satoyama, such as food and nature experiences.

This report is a case study of the Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama project, based on field surveys and interviews conducted by the authors from April 16 to 19 and June 13 to 14, 2022. Section 1 outlines the Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama and the surrounding landscape of Uehara, as well as the history of the area up to the restoration project. Section 2 outlines the Satoyama restoration efforts, particularly citizens’ tree planting, and activities to restore the human-nature relationship in the Satoyama. Section 3 presents four key perspectives of Satoyama restoration drawing on the case study results, followed by conclusions in Section 4

1. Landscape and history surrounding the Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama

The Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama is located on a plateau, called Uehara, at the top of a small mountain range that forms the southeastern tip of the Shimabara Peninsula of Nagasaki Prefecture. Along the coast about 3.5 km east down of Uehara are the ruins of Hara Castle (Figure 1.a), which is one of the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Sites “Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region”, and is the site of the Shimabara-Amakusa Rebellion that took place 385 years ago. It is also the original hidden Christian site, leading to other sites being designated in Nagasaki and Kumamoto Prefectures. The following is a brief description of the history of Christianity in the southeastern Shimabara Peninsula in the context of its landscape development, and the landscape changes in Uehara that led to AEON Satoyama project proposal in Minami-Shimabara.

1.1. History of Christianity in Minami-Shimabara

Centered on the area of present-day Minami-Arima town and Kita-Arima town in Minami-Shimabara City was Hinoe Castle (Figure 1.b), residence of the Arima clan, made up of warring feudal lords who extended their power throughout the Shimabara Peninsula and into Saga Prefecture from the 14th to the early 17th centuries. The Arima clan prospered through trade with Portugal, and was headed by a Christian feudal lord who supported Catholic missionary works. The 13th lord of the clan, Arima Harunobu, was baptized in 1580, which spread the Catholic faith among his vassals and subjects. In the same year, Harunobu opened the Seminarios (Figure 1.c), the first European-style school in Japan where students studied various subjects. In 1582, four boys were selected from this school to join the first Japanese mission to Europe, known as the Tensho youth mission to Europe, traveling to Portugal, Spain, Italy, and the Vatican, where they were received by the Pope. They were the first recorded Japanese that Europeans encountered in Europe.

While these exchanges with Europe flourished, the persecution of Christianity had begun in Japan: Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who came to power in Japan in 1586, issued an edict banning missionaries in 1588, followed by Tokugawa Ieyasu, who founded the Edo shogunate in 1603, issuing a prohibition on missionaries in 1614. During this period, Arima Harunobu was executed in 1612 due to a political dispute, and his successor Arima Naozumi was transferred to Hyuga (present-day Miyazaki Prefecture) in 1614 when the Shimabara Peninsula temporarily became a territory under direct control of the shogunate. The Matsukura clan, under a Nara region-based feudal lord, arrived in this vacuum to govern the Peninsula, and enforced policies of heavy taxation to build a new castle and of violent prohibition of Christianity. These policies, as well as famine, drove the people of the land into a state of exile.

Suppression from the shogunate and the new lords forced the Catholic faith underground. Alessandro Valignano, the Jesuit priest who baptized Harunobu and led the Tensho youth mission, reported to the Jesuits in 1590 that there were groups of firm Catholic faith (confraria) in the area where missionaries were absent due to the Hideyoshi’s 1588 edict, and indicated the potentially important role of confraria to maintain Christianity in Japan in an era of opression. The Jesuit missionary Giacomo Antonio Gianone, who came to Japan in 1609, worked in the confraria of Onuki Village on the Shimabara Peninsula and reported to the Jesuits about rules held by several confrarias in Shimabara. His confraria was presumed to be located in Bomeki hamlet just north of the Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama on Uehara plateau, because of the similarity to the historical name of Onuki, as well as due to the presence of a Jizo statue of unique motif that was said to have originated in Europe (Figure 1.d, Figure 2).

The devout Catholic faith rooted in the people of the region through the confraria, in the face of brutal Christianity oppression and heavy land taxation, developed into an unprecedent collective resistance against the feudal lord and the shogunate. This is said to have resulted in the Shimabara-Amakusa Rebellion of 1637. The Shogunate thoroughly suppressed the revolt, killing most of the local residents who had joined the rebel forces, completely destroying their stronghold, Hara Castle, and other structures. This event symbolized the 285 years of Christianity prohibition in Japan, from Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s decree banning missionaries to the abolition of Christianity prohibition by the Meiji government in 1873. After the Shimabara-Amakusa revolt nearly wiped out the territory, immigrants settled in Minami-Shimabara from all over western Japan, and many of the people who live in Minami-Shimabara today trace their roots to these immigrants.

There is no agreed time in history as to when the spectacular rice terrace landscape on the hills of Uehara that we see today was formed. Nevertheless, the rice terrace landscape is a priceless heritage of the efforts and ingenuity of the ancestors of Minami-Shimabara, who were struggling with little water and flat land, and had endured a history of hardship including heavy land taxation, Catholic suppression and mass immigration after the Shimabara-Amakusa Rebellion.

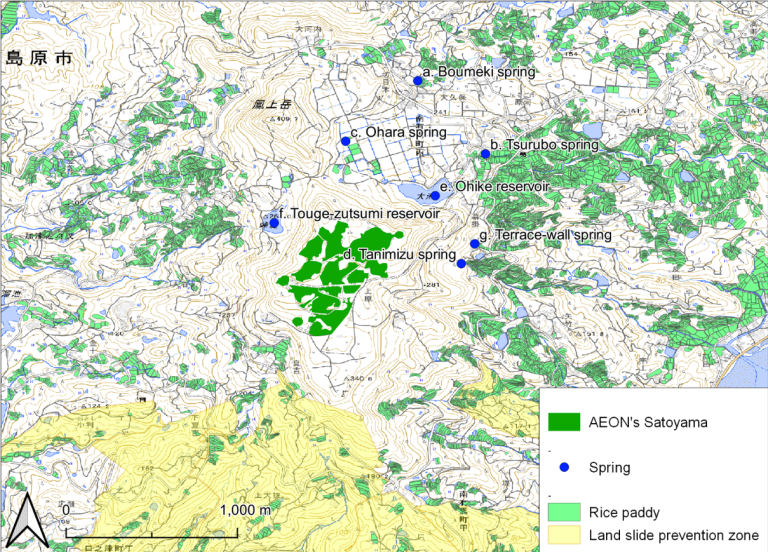

1.2. Transition of the landscape around Uehara

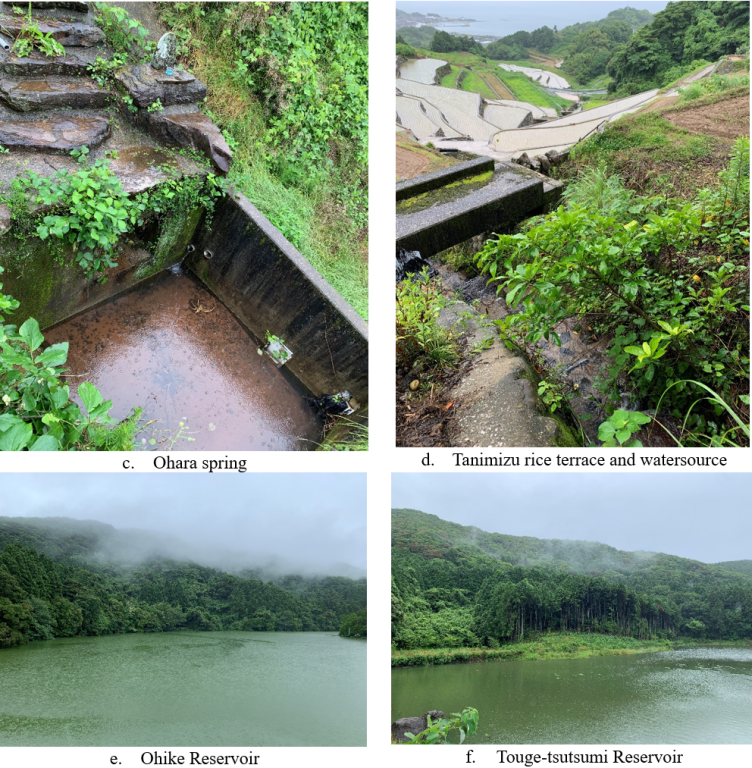

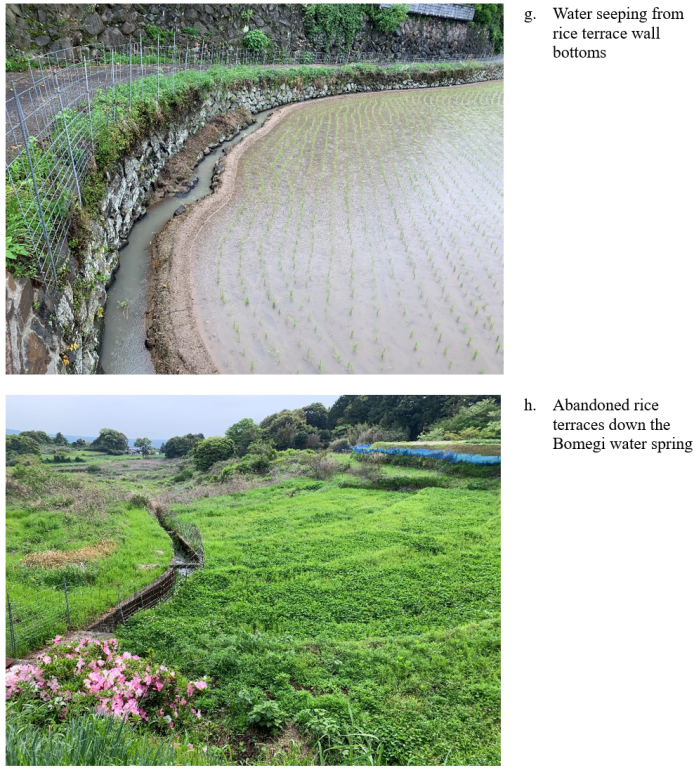

The mountain range at the southern tip of the Shimabara Peninsula, which is peaked by the Uehara plateau, has limited surface water due to its geology and topography. The rice terrace landscape surrounding Uehara shows the farmers’ knowledge, efforts and struggles over many generations as they tried to produce food with limited water, despite the fertile volcanic soil and abundant sunlight on the southern slope. After descending the steep slope that borders the volcanic rock plateau, the terrain changes to a gentle slope of sedimentary rock towards the foot of the hill, where numerous water springs are found (Figure 3.a~d). Some of these springs have a stable water flow and have long been used for irrigating rice paddies as well as for drinking and other domestic use by residents, and thus they are typically deified. There are also numerous reservoirs that stabilize the water supply to the rice paddies even during dry seasons and droughts (Figure 3.e, f). Even the smallest of these reservoirs has the capacity to sustain water supply to paddy fields for 20 days without rainfall. This is based on the farmers’ rule of thumb that water source depletion in summer droughts seldom lasts longer than 20 days. Besides, some paddies directly use water seeping out from the bottom of the top terrace walls, which is then channeled down to the lower paddies (Figure 3.g). The rice terraces do not only produce food but also make important contributions to watershed protection and landslide prevention, considering particularly the location of water sources and rice paddies on high landslide risk areas.

The authors visited Bomegi hamlet for a field study, and there, the residents recalled their daily life around 1950, shortly after WWII, when they shared water from one source:

There were shared rules as to the use of water at the spring, e.g., the headwater was used for drinking, water downstream was used for cooking, washing vegetables and then further down, for washing clothes. The water finally flowed down the waterway to irrigate the rice terraces. Water was too precious to be used for bathing in each of around 46 households in Bomegi around that time. So one house took it in turn to prepare hot water in the bath for all the neighbors. The children went to fetch water on a daily basis. Even after electricity was installed and an electric pump was used to draw water from the spring to each house, there was still a rule that when water was scarce, people would fetch water without using the pump. When there was a shortage of water, there would sometimes be a dispute over the water to be drawn to the rice paddies, and people would sometimes stay up at night guarding the water in the paddies to prevent others from taking it. At New Year’s, there was a ritual called Wakamizu-kumi (meaning fetching the first water of the year), where one person from each house went to fetch water for the first meal of the year, ozoni, after the new-year bell of the temple rang. In this ritual, no one else was allowed to see or be seen. Back then, people didn’t have money, but they had generous hearts.

Nowadays, these rice terraces are being abandoned due to high maintenance cost and low productivity. Rice terraces immediately below the Bomegi water spring are not exemptions (Figure 4.h). According to a resident, rice terraces are being abandoned year after year, as compared to the retained use of improved larger rice paddies with modern irrigation and concrete walls for higher productivity. Widespread abandonment of rice terraces does not only mean reduced economic activities but there is a concern that this will increase the risk of landslides.

On the Uehara plateau, where the “Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama” is now located, was a secondary forest where local people used to collect firewood and charcoal until the end of WW II. Around 1945, the forest was cleared for cultivation by settlers returning from WW II, when potatoes and wheat were produced. The production, however, was not commensurate with the labor due to water scarcity. In 1978, a radio transmitter station was built here for communications with ships sailing south of Japan (Figure 5), which, according to the residents just below the plateau, started affecting their water sources. After the radio transmitter station was closed and removed in 1999, the former Minami-Arima Town, currently one of the eight districts comprising Minami-Shimabara City, acquired the land and proposed restoring a citizen’s forest for watershed protection and disaster risk reduction.

2. Restoring Satoyama and human-nature relationships

2.1. Restoration of Satoyama through tree planting

In 2006, eight municipalities in the south-east of Shimabara Peninsula, including Minami-Arima town, merged to form Minami-Shimabara City. In 2008, the new city’s General Plan prescribed a plan for reforestation activities to enrich the natural environment as a priority policy for nature conservation. In 2009, Minami-Shimabara City requested cooperation from the AEON Environmental Foundation to carry out tree planting on the site of the former radio transmitter station in Uehara. Subsequently, a memorandum of understanding (MOU) was signed by the two parties on 9 March 2010 agreeing to cooperate in tree planting in Uehara. The MOU stipulated that tree planting over a total area of 20.5 hectares would be carried out three times over a three-year period with citizen participation. The first planting was scheduled for November 2010 (Figure 6). Being mandated to prepare for this large-scale participatory tree planting, the “Minami-Shimabara Citizen’s Forest Planting Executive Committee” was established on 26 March 2010. The prospectus for the establishment of the executive committee clearly states its objectives: “to hand down nature to the next generation” and “to protect and nurture the forest through the cooperation of citizens and the municipal government”. It also mentions various forest ecosystem services, including freshwater, ocean nutrients supply, disaster prevention, maintenance of living environment, health and recreation, air purification and climate change mitigation. The prospectus further specifies the role of the executive committee to help citizens recognize the importance of forests, to attract their interest in reforestation and to invite them to participate in activities to restore and protect the forest. The executive committee is characterized by diversity in its membership, i.e., 39 organizations spanning different sectors, generations and regions. These include the municipal government, forestry, agriculture, fishery, commerce, and tourism sectors, water supply and other infrastructure, education, private sector companies including AEON Kyushu, environmental NPOs, charitable organizations such as Lions Club and Rotary Club, as well as women’s associations, youth associations and senior citizens associations, from across the eight districts.

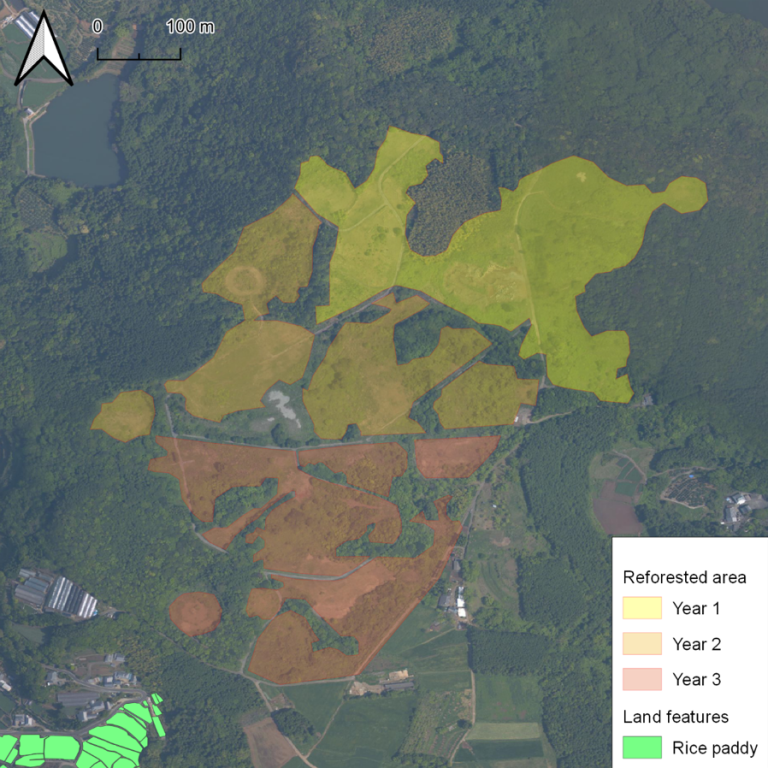

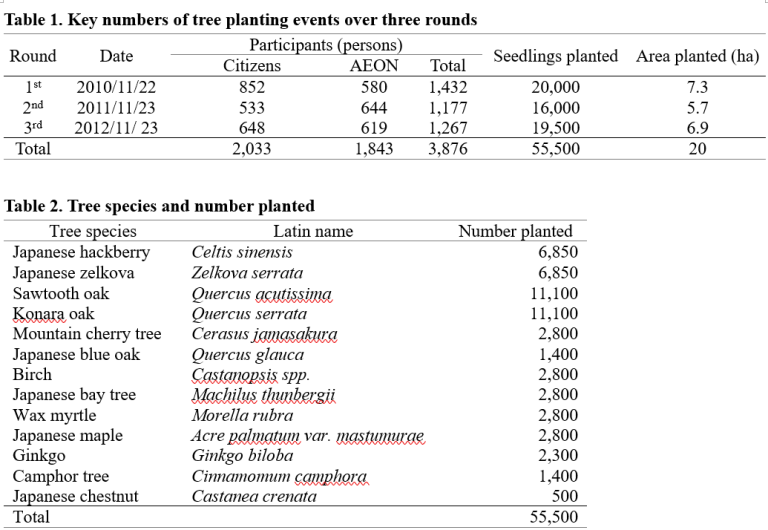

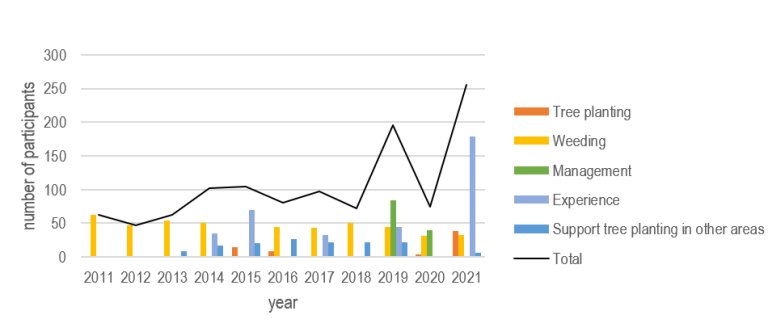

Tree planting was conducted once in November of each year for three years from 2010 to 2012. A total of 3,876 people participated, including 2,033 Minami-Shimabara citizens and 1,843 AEON staff (Table 1). A total of 55,500 trees of 13 species (Table 2) were planted over approximately 20 hectares (Figure 7). After the tree planting, local volunteers have been engaged in weeding and thinning every year. Year after year, the type of activities and participants have become diversified to include chestnut picking and eating, additional planting of mountain cherry trees, bamboo forest management and other hands-on forest learning activities. Beyond the Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama in Uehara, the executive committee extended its activity to cooperation with reforestation in other areas, including Aya Town in Miyazaki Prefecture, the AEON Forest in Taketa City, Oita Prefecture, and tree planting cooperation with the AEON Shimabara store. The cumulative number of participants in these series of activities since tree planting reached 1,153 by FY2021 (Figure 8).

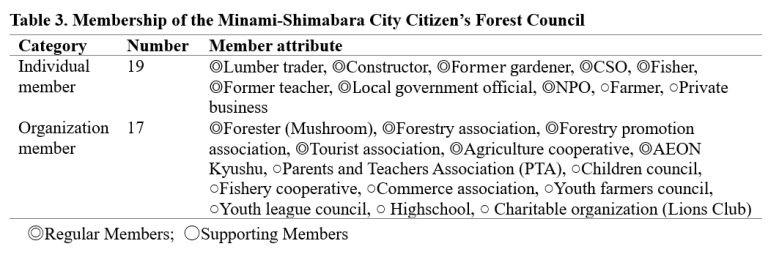

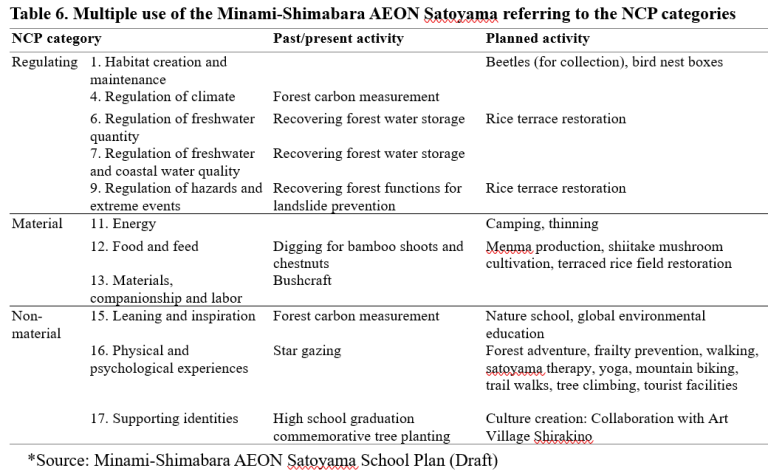

2.2. Creating new human-nature relationships through the use of Satoyama

Ten years have passed since the first tree planting, and as the Satoyama has grown and continued to be cared for, it has begun to show signs of functional recovery, such as water source recharge and land protection, which were the original goals of the project. The Satoyama further started providing additional produce to people such as bamboo shoots and chestnuts. The recovery of Satoyama and its ecosystem services required shift in the focus of activities from reforestation to forest use by citizens. In response, the executive committee was renamed and restructured to become the “Minami-Shimabara Citizens’ Forest Council” (Table 3). Since then, activities have continued to be diversified, despite being temporarily suspended from 2020 to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These hands-on activities include bamboo shoot harvest in the spring, bush-craft in the summer, forest experiences such as chestnut picking and eating as well as star gazing in the fall. There have also been activities such as forest carbon measurement by local elementary school students and commemorative tree planting by graduating high school students across the Shimabara Peninsula (Figure 9).

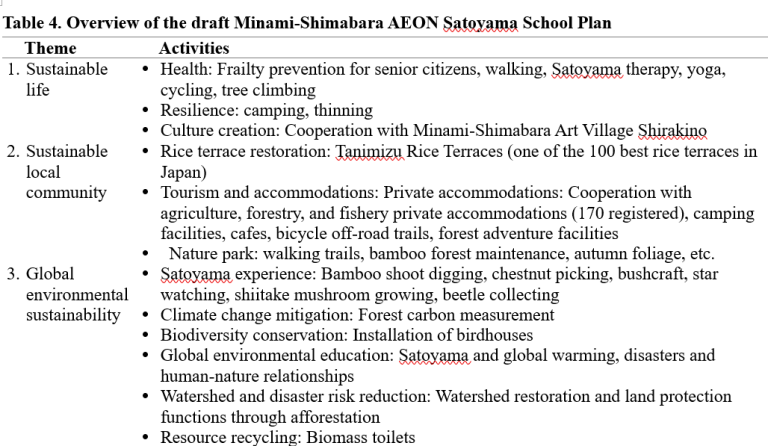

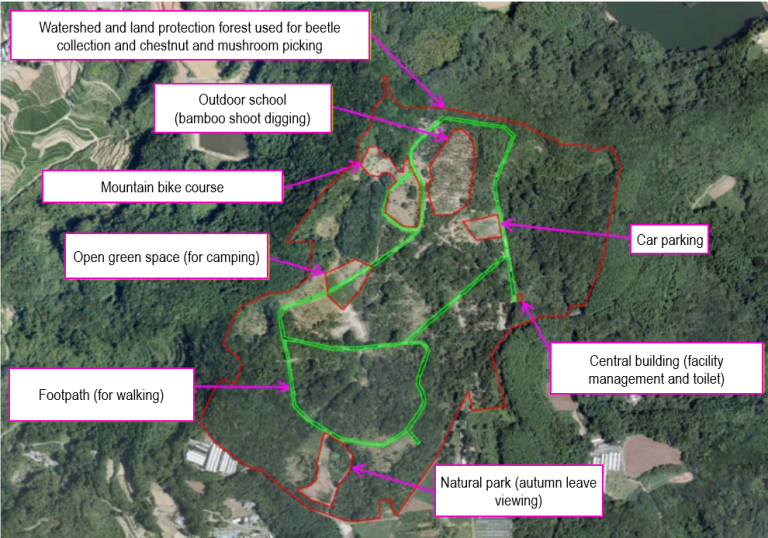

In order to further increase the range of activities, the council is also visiting other areas to learn about progressive actions, such as bamboo shoot processing, forest adventures and nature schools. Currently, the municipal government and the council are working to develop the “Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama School Plan” (Table 4) and the “Uehara Citizens’ Forest Development Plan Basic Concept” (Figure 10) to ensure that local citizens make multiple use of the Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama in the future, including for recreation, food experiences, health, local culture learning and global sustainability education.

3. Key perspectives for Satoyama restoration

The landscape history of Minami-Shimabara described in Section 1, as well as the developments and outcomes of the Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama project outlined in Section 2 provide four key perspectives for restoring human-nature relationships through Satoyama restoration. These are multi-actor collaboration, universal use of Satoyama, landscape approach and land history. The subsections below discuss these points in detail.

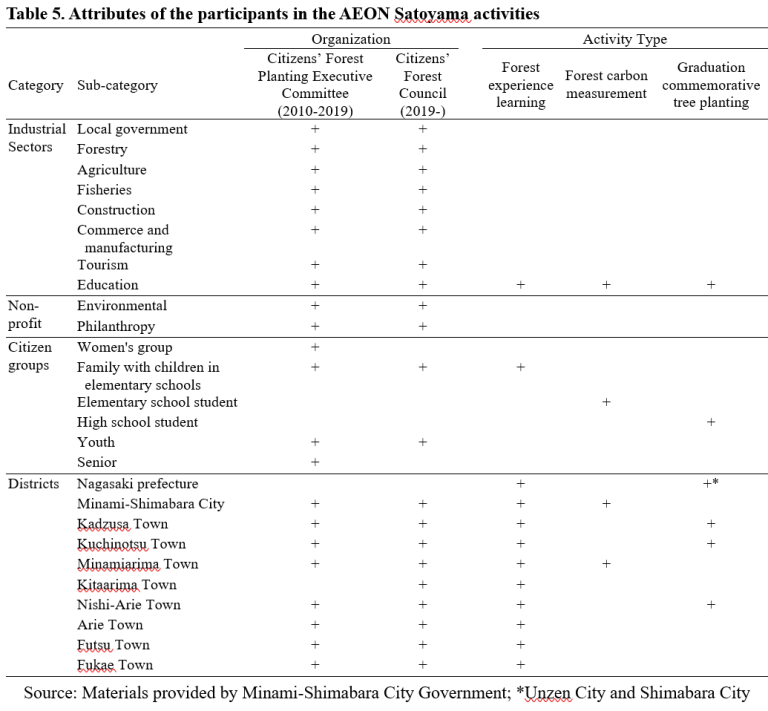

3.1. Local government and multi-actor collaboration

The Minami-Shimabara Citizens’ Forest Planting Executive Committee and the succeeding Minami-Shimabara Citizens’ Forest Council have played a central role in the series of developments. These entities are characterized by diversity and inclusiveness in their membership as described in Section 2.1, including several sectoral divisions in the local government, businesses from major industrial sectors, non-profit organizations as well as youth, senior and women’s groups from across the eight city districts (Table 5). Developing, sharing and continuing diverse field activities for restoring, managing and using Satoyama by multiple actors have resulted in effective collaboration.

The inclusive membership of the Citizens’ Forest Planting Executive Committee and the Citizens’ Forest Council has contributed to the continuous developments of Satoyama restoration activities. Usually government officers in Japan, including the Minami-Shimabara City Government, are subject to periodic position transfer every two to three years, which makes it difficult for them to continue novel actions such as this beyond their legally-bound routine administration. In this case, nine of the Minami-Shimabara City government officials have been engaged in Satoyama restoration activities not only as part of their duties during their time in office but continuously as individual members of the Citizens’ Forest Planting Executive Committee or the Citizens’ Forest Council. This has helped to ensure that successors in the office continue to carry out Satoyama restoration activities, and then newly involve other offices where the former officer in charge is transferred.

Furthermore, the Citizens’ Forest Council has been providing opportunities for citizens to interact with nature through activities, such as forest experience learning for families with elementary school children, forest carbon measurement with the graduating elementary school students, as well as commemorative tree planting by graduating high school students across the whole Shimabara Peninsula. In addition, these activities provide valuable opportunities for cooperation among citizens of the eight districts of the city, who may not usually interact with each other due to geographical distance (Table 5). The diverse activities require a broader knowledge base, which the Citizens’ Forest Council effectively provides through its members who have various expertise, including local government, agriculture, forestry, and fisheries and education.

3.2. Local government and multi-actor collaboration

The Minami-Shimabara Citizens’ Forest Planting Executive Committee and the succeeding Minami-Shimabara Citizens’ Forest Council have played a central role in the series of developments. These entities are characterized by diversity and inclusiveness in their membership as described in Section 2.1, including several sectoral divisions in the local government, businesses from major industrial sectors, non-profit organizations as well as youth, senior and women’s groups from across the eight city districts (Table 5). Developing, sharing and continuing diverse field activities for restoring, managing and using Satoyama by multiple actors have resulted in effective collaboration.

The inclusive membership of the Citizens’ Forest Planting Executive Committee and the Citizens’ Forest Council has contributed to the continuous developments of Satoyama restoration activities. Usually government officers in Japan, including the Minami-Shimabara City Government, are subject to periodic position transfer every two to three years, which makes it difficult for them to continue novel actions such as this beyond their legally-bound routine administration. In this case, nine of the Minami-Shimabara City government officials have been engaged in Satoyama restoration activities not only as part of their duties during their time in office but continuously as individual members of the Citizens’ Forest Planting Executive Committee or the Citizens’ Forest Council. This has helped to ensure that successors in the office continue to carry out Satoyama restoration activities, and then newly involve other offices where the former officer in charge is transferred.

Furthermore, the Citizens’ Forest Council has been providing opportunities for citizens to interact with nature through activities, such as forest experience learning for families with elementary school children, forest carbon measurement with the graduating elementary school students, as well as commemorative tree planting by graduating high school students across the whole Shimabara Peninsula. In addition, these activities provide valuable opportunities for cooperation among citizens of the eight districts of the city, who may not usually interact with each other due to geographical distance (Table 5). The diverse activities require a broader knowledge base, which the Citizens’ Forest Council effectively provides through its members who have various expertise, including local government, agriculture, forestry, and fisheries and education.

3.3. Spatial scale: Landscape approach

The multifunctionality of Satoyama implies the importance of the landscape perspective which not only looks at the changes within the restored site but the consequences in the surrounding landscape. For example, water storage and purification and land protection functions of the restored site on the Uehara plateau indicates its benefits to farmland and settled areas further down the slopes in terms of water supply and disaster risk reduction. Water deriving from this watershed has been used for generations to meet living needs and to irrigate rice paddies. Nowadays, however, the maintenance of the Satoyama landscape and culture that flourished using this water has become increasingly difficult due to population decline and land abandonment. In the Shirakino area located at the southeastern foot of Uehara, abandoned farmland increased from 14 to 24 hectares between 2010 and 2021. Therefore, along with the restoration of watershed forest, it has become a pressing issue to maintain and pass on the unique Satoyama landscape to the next generation, particularly rice terraces and traditional culture, so that precious water sources can be protected and used effectively.

3.4. Time Scale: Land history, cultural identity and peace education

The potential educational use of the AEON Satoyama and surrounding landscapes on and around Uehara should also be noted. Recently the SDGs and global environmental sustainability have become important subjects in schools but ironically children have lost the direct experience of nature that they had when playing in fields and forests in the past. Under these circumstances, Satoyama activity programs such as those offered by the Citizens’ Forest Council, can provide vital opportunities for children to learn by directly experiencing local nature and culture. These experiences will encourage not only children, but also all citizens and visitors from outside the area, to participate in activities to maintain the local Satoyama landscape and to pass it on to future generations.

Furthermore, the area has unique potential for learning about history and peace from Minami-Shimabara’s past as a cosmopolitan city from the 16th century that was the first in Japan to have exchanges with Europe and to adopt Western-style education, as well as reflecting on the resulting tragedy of the Shimabara-Amakusa rebellion. Bomegi ward located below the Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama has an Enzu jizo statue encapsulating the hidden Christian culture. Further down the mountain are the ruins of Hara Castle, Hinoe Castle, Seminario, and countless Christian tombstones. For more than 20 years, junior high schools in Minami-Shimabara have been conducting experiential learning programs that recreate the history of 400 years ago, including Festivitas Natalis (Christmas), ancient European cuisine, Seminario classes and junior-high school trip to Italy. The draft Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama School Plan proposes collaboration with the Minami-Shimabara City Art Village Shirakino, located at the foot of the mountain. Here, efforts are underway to revitalize local culture by supporting young print artists from all over Japan, linking to the roots of the area which was where Catholic missionaries made first copper prints in Japan.

Envisioning increased participation from eight districts of Minami-Shimabara and outside in the future, AEON Satoyama program could focus on peace education and local culture transmission rooted in the unique history of the area.

4. Conclusions

This paper discussed the role of Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama as a symbol to restore human-nature relationships, based on the history of the area and a case study of the activities to restore and revitalize the use of Satoyama. From this, we presented four key perspectives for the restoration of Satoyama that represents unique and improved relationships between humans and nature.

The first is the important role of a coordinating body to facilitate multi-actor collaboration including government and private entities, as well as the importance of Satoyama that provides afield for collaboration. Second, universal use of Satoyama drawing on its multi-functionality can encourage the participation and transformative actions by a wide range of actors. Third, it is vital to have a landscape approach, which not only looks at the restoration site but extends this view to interactions with surrounding areas, thereby understanding Satoyama as the representation of locally unique human-nature relationships. The fourth is time scale. Understanding the present landscape from historical interactions with people for generations since ancient times provides important insights into how we can engage with the landscape in the future.

Ten years have passed since the start of the restoration, and the Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama is now at a turning point, going from restoration to sustainable use. Furthermore, Satoyama activities are being diversified, due to the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic period from 2020 to 2021. Therefore, it is hoped that future developments in Minami-Shimabara AEON Satoyama will provide further knowledge and experience that will be useful for Satoyama restoration in other areas.

In addition, citizen groups are collecting seeds in forests near Minamihama with the help of volunteers. Figure 9 is a satellite image of the area around Minamihama. The narrow strip of green space just north of Minamihama is the Mt. Hiyoriyama forest, and the hills to the east across the Kitakami River make up the Makiyama forest. The citizen’s group “Kokoro-no-Mori”, as a member of the participatory council, has been collecting seeds from Mt. Hiyoriyama and Makiyama forests and began growing seedlings in a greenhouse nursery set up in the northern part of the Minamihama district in the fall of 2014. In 2014, the water supply to the Minamihama district had not been restored, so the founder of Kokoro-no-Mori filled buckets with water at his home and carried them to the greenhouse nursery in Minamihama to water the seedlings. Later, in the fall of 2016, a study council was formed, and in 2017, the greenhouse nursery for seedlings was relocated to an area inside the memorial park, where seed collection from the forest and seedling production continue.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Seiki Nagahashi, Chairman of the Minami-Shimabara Citizens’ Forest Council, Mr. Hironori Takagi, Secretary General of the Council, Mr. Hiroaki Matsumoto, Director of Education of Minami-Shimabara City, Mr. Takeshi Baba, Tanimizu Tanada Conservationist and Historical Guide, Mr. Tetsutoshi Uchiyama, Chairman of the Minami-Shimabara Tourism Association, Mr. Toru Suenaga, a member of NPO Arimanban for their cooperation to our study. We extend our thanks to the residents of Minami-Shimabara City for their generous cooperation to interviews. We also thank the AEON Environmental Foundation for its support in conducting the survey.

References

IPBES. 2019. summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio E.S., H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. 56 pages.

Kawamura, Shinzo. 2003. The Birth and Transformation of the Christian Congregation. Kyobunkan.

AEON Environmental Foundation, Minamishimabara City. 2010. Memorandum of Understanding on Tree Planting in Minami-Shimabara, Nagasaki Prefecture.

Minamishimabara City. 2014. Minami-Shimabara Historical Heritage – Visiting Christian Historical Sites with a Focus on the Ruins of Hara Castle, Hinoe Castle and Kirishitan Tombstone. Produced by Nagasaki Bibliography, Printed by Daido Printing Co.

Minami-Shimabara City Uehara Area Development Study Committee. 2021. Uehara Citizen’s Forest Development Plan Basic Concept.