Enhancing Livability Through Urban Land Conservation: NeighborSpace of Baltimore County, Pocket Parks, and Retrofitting URDL

08.11.2022

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

DATE OF SUBMISSION

18/08/2022

REGION

Americas

COUNTRY

USA

KEYWORDS

Urban Land Conservation, Park Access, Retrofitting, Green Infrastructure, Climate Resilience

AUTHORS

Kristen Wraithwall, research consultant to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here.

Executive Summary

The social, environmental, and economic conditions of present-day Baltimore County are the result of a series of planning, funding, and conservation decisions dating back to the post-World War II era, a period which the Baltimore City Planning Department refers to as a period of “suburbanization without end.” Bolstered by Federally-subsidized home loans and an influx of soldiers returning from war, the Counties surrounding Baltimore City expanded at astonishing rates in the decades following WWII; by the 1950s, between 7,000 and 8,000 homes were being constructed each year in the Baltimore suburbs. At the same time, the City population dropped—by 10,000 in the 1950s and 35,000 in the 1960s—as white residents fled to the suburbs and low-income and African American communities were forced to relocate as the City demolished entire neighborhoods for the creation of highways.1

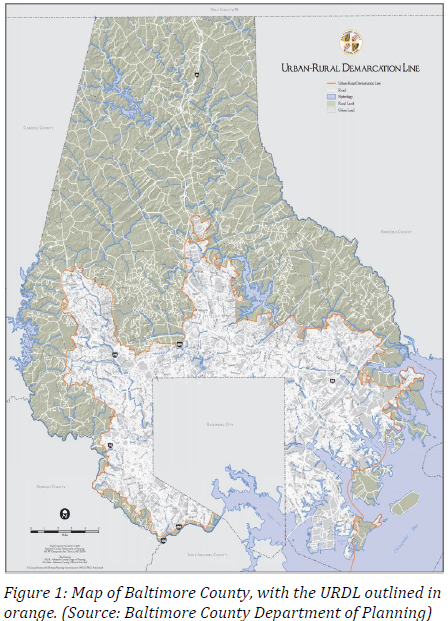

Rapid suburbanization compounded by a reliance on single-use zoning throughout the mid-twentieth century meant that Baltimore County developed as a series of car-dependent “bedroom communities” around major transportation corridors with limited walkability and few—if any—open spaces. Redlining and rampant discrimination exacerbated these challenges in communities of color, as these communities intentionally received fewer federal housing loans and less government investment. While Baltimore County attempted to curtail sprawl in 1967 by establishing an urban growth boundary called the Urban-Rural Demarcation Line (URDL), much of the damage had already been done. Today, nearly 70 percent of residents in Baltimore County lack access to open space within a quarter mile of their home and all but one of the watersheds in the region are polluted by stormwater runoff.

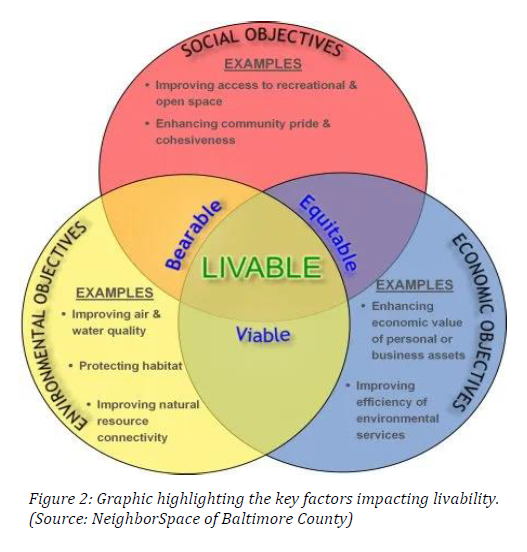

NeighborSpace of Baltimore County (NeighborSpace) was founded in 2002 to begin to address the dearth of open space within the County. By protecting and improving green space for small pocket parks, gardens, trails, and other natural areas, NeighborSpace seeks to improve livability throughout the URDL. NeighborSpace defines livability by the sum of social, environmental, and economic factors that impact quality of life, a guiding principle has driven NeighborSpace to conserve 21 parcels totaling 100 acres within the County. They have achieved success by developing close working relationships with the Baltimore County Government, local universities, and most importantly, community-based organizations. These partnerships have enabled NeighborSpace to establish itself as the go-to organization for urban and suburban land conservation in the Baltimore area.

NeighborSpace has taken the toolkit for large landscape conservation in rural areas and turned it on its head in order to fit parcels as small as 0.15 acres in urban and suburban environments. In partnership with the National Park Service, it has developed a first-of-its-kind GIS prioritization methodology for assessing the conservation value of a parcel of land based on its potential for improving the social, environmental, and/or economic factors of livability of the nearby community. This resource—which relied heavily on the feedback and stated priorities of residents—is one of the many ways in which NeighborSpace can serve as a leader and a model for other urban and suburban land trusts across the United States.

Introduction

Baltimore County is a classic first-tier—also known as inner ring or mature—suburb. First-tier suburbs were generally developed close to the city center, often as bedroom communities for city commuters.2 The development of many first-tier suburbs, including Baltimore County, was driven by a combination of factors including the creation of the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) in 1934 which guaranteed private mortgage loans, and the VA mortgages enabled by the GI Bill of 1944 which paid for the construction of nearly 5 million new homes.3 Coupled with the availability of inexpensive mass-produced housing, Baltimore City residents began moving to the suburbs at astonishing rates after World War II. Just how fast was this move? “It was like putting a match to a pile of drywall,” said Barbara Hopkins, Executive Director of NeighborSpace of Baltimore County.

The remarkably rapid development of Baltimore County’s inner suburbs occurred, in part, because it was largely uninhibited by planning processes. Euclidean zoning, also known as traditional zoning, provided the only framework for the County’s development. Characterized by the designation of single-use districts and strict building codes, Euclidean zoning emerged in the 1920s to prevent the industrialization of residential areas.4 Despite potential benefits for air quality in select neighborhoods, Euclidean zoning has exacerbated segregation, car-dependency, sprawl, and inequality in many first-tier suburbs, while increasing housing costs and worsening walkability.5 In Baltimore County, this has led to the creation of what NeighborSpace described as an “Ordinary Landscape” – communities that are car dependent, transected by busy traffic corridors that transport residents in and out of the city as quickly as possible, and strip malls that, at first look, could be almost anywhere in the United States.6

Furthermore, the practice of redlining—systemic and strategic disinvestment in communities driven by racial bias—during this period of expansion led many communities of color throughout the County to have substantially less access to green spaces, as well as greater exposure to other negative social, economic, and environmental conditions.7 While these issues are pronounced in Baltimore County, the effects of redlining are felt by communities of color across the US; nationwide, communities of color are three times more likely to experience nature deprivation than white communities.8

The geographic sprawl of Baltimore County began to slow in 1963 when Ian McHarg drafted The Plan for the Valleys. While many of McHarg’s views—particularly his theory of ecological determinism9—have been critiqued in recent years, The Plan for the Valleys served as a catalyst for landscape conservation in the County. The most direct manifestation of McHarg’s work was establishment of the Urban Rural Demarcation Line (URDL) in 1967. The URDL limited growth and development to Baltimore’s inner suburbs by prohibiting water and sewer utilities outside of its bounds.10 More than 40 years after the growth boundary was established, 90 percent of Baltimore County’s nearly 850,000 residents live on just one third of the land area.11 As a result, communities within the URDL are experiencing many of the challenges characteristic of aging first-tier suburbs, including limited access to green space, high levels of stormwater runoff, degraded infrastructure, loss of industry, growing food insecurity, and poverty.

Together, these factors impact livability within the URDL – conditions that NeighborSpace of Baltimore County was created to address. The organization—formally established by County Resolution in 2002 and incorporated as a non-profit in 2003—was created in order to improve the livability of communities within the URDL. NeighborSpace defines livability as the sum of factors that add to a community’s quality of life, including social, economic, and environmental factors. They support livability by protecting and improving green spaces such as pocket parks (some even smaller than a single house lot), gardens, trails, and other natural areas.12 To date, they have conserved 21 parcels totaling 100 acres throughout the URDL.

Since 2009, NeighborSpace has been led by Barbara Hopkins, who has built the organization from a small grassroots group, to a key thought partner of Baltimore County. Steve Lafferty, the County’s Chief Sustainability Officer, described the scale of NeighborSpace’s work as being complementary to the work of the County on many levels. “[The County] doesn’t have the on-the-ground capacity to go into a neighborhood and build up stewardship at the scale NeighborSpace is doing.” While the County may not have the capacity to maintain a patchwork of small pocket parks throughout the County, these small-scale projects are a critical piece of the County’s strategy for using land preservation as a climate resilience tool.

In addition to working hand-in-hand with the County, NeighborSpace accomplishes their work thanks to close partnerships with organizations ranging from regional water quality and environmental nonprofits to small community associations to Morgan State University, the largest historically Black college or university (HBCU) in Maryland. Hopkin’s ability to create meaningful relationships with the community has been central to the success for NeighborSpace. “She’s a godsend,” shared Aaron Barnett, President of the Powhatan Farms Improvement Association. At the 2018 opening of the Powhatan Park, Barnett reflected, “together with NeighborSpace, we’ve turned an eyesore into a vision of beauty. I wouldn’t trade my community for any other in the world.”Among other benefits, Lafferty noted that pocket parks and rain gardens maintained by NeighborSpace are important tools for helping the County manage localized flooding.

Problem Statement

Within the URDL, decades of unchecked development, densification, and disinvestment have impacted livability in numerous ways. Most central to NeighborSpace’s mission is the “chronic shortage of open space” in the URDL, thanks to a history of limited regulations governing development and open space requirements. As a result, 70 percent of residences within the URDL have inadequate access to open space within a quarter-mile of their home. The dearth of green spaces has a suite of cascading environmental, economic, and social challenges that NeighborSpace is working to address.

Environmentally, high rates of impervious surface cover and limited green infrastructure have increased stormwater runoff within the URDL. Without green spaces to serve as critical filtration systems, runoff has polluted the Chesapeake Bay as well as the County’s other urban water resources. In addition to providing water purification benefits, green spaces have air quality and climate mitigation benefits as well. Without the localized cooling benefits provided by green spaces—which cool surrounding areas by up to 10 degrees Fahrenheit13—communities within the URDL experienced heightened urban heat impacts. Within Baltimore County, these heat impacts are often felt most strongly by low-income communities and communities of color, groups that are already more vulnerable to climate change.14 Furthermore, the majority of communities have walk scores below 50, categorizing them as car dependent and largely un-walkable, which has both public health and environmental implications for residents.15

Economically, median home values in Baltimore County are among the lowest of all jurisdictions in the Baltimore Metropolitan area16 and 15 percent of children are food insecure.17 By developing green spaces in partnership with community members, NeighborSpace hopes to enhance property values within the URDL. They are also exploring urban gardens as an opportunity for improving local food sovereignty.

Socially, local communities are missing out on important opportunities to not only recreate, but also to enhance community cohesiveness. Without adequate access to green spaces, residents within the URDL lack a critical resource for building resilience – shared green spaces contribute community wellbeing, social network development, cross-cultural exchange, and societal empowerment.18 The development of open spaces can improve community resilience before and after natural disasters by creating venues for enhancing communication and promoting collaboration among diverse community members.19 Additionally, access to green space is tied to both physical20 and mental health benefits.21

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has complicated many of the social problems facing Baltimore County residents. On one hand, “open space has benefitted from COVID” said Klaus Philipsen, NeighborSpace Board President. “[It] has seen a dramatic increase in use, particularly in Maryland, during the pandemic,” which underscores the need for increased investment in urban land conservation. Another NeighborSpace Board Member, Kathy Martin, says that the small, local parks that NeighborSpace focuses on have played an especially important role during the pandemic. She highlighted that residents may feel more comfortable using a small pocket park shared by their neighbors as opposed to a large community park that they need to drive to. Putting it simply, with COVID-19, Martin said, “you are spending more time in your community.”

While the pandemic has highlighted important conversations about the value of urban green spaces, it has also halted many of the in-person gatherings that community groups relied on to plan the ongoing management of their NeighborSpace park sites. Dale Cassidy of the Ridgely Manor Community Association said that COVID-19 has prevented Ridgely Manor park volunteers from meeting for months. Other community organizations are trying out a variety of online and distanced meet-ups to ensure their park spaces are maintained. Another perennial problem exacerbated by the pandemic is funding. Steve Lafferty explained, “the County budget took a huge hit as a result of the budget” something he noted is going to take a while to rebuild. Yet despite these challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided a unique opportunity for urban land trusts like NeighborSpace to rise to meet the growing—and urgent—demand for urban green spaces.22,23

Strategy and Implementation

NeighborSpace’s vision is “for all residents inside the URDL to be able to enjoy a park, garden, trail, or natural area without having to drive a car to get there.” Achieving this vision requires NeighborSpace to undertake four key strategies:

1. Focusing on retrofitting.

2. Developing a prioritization model.

3. Working in close partnership with the County of Baltimore.

4. Following the community’s lead.

Focusing on Retrofitting

In their conservation work, NeighborSpace has drawn inspiration from Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson’s 2009 book, Retrofitting Suburbia. While the redevelopment of city centers and the careful planning of emerging suburbs have received significant attention in recent years, there has been limited attention given to the redesign of existing suburbs. 24Particularly in aging first-tier suburbs like Baltimore County where redevelopment funding is limited or nonexistent, Retrofitting Suburbia—or as NeighborSpace likes to say, Retrofitting “SubURDLia”—involves weaving walkability and sustainability into the existing suburban fabric.25 Board President Klaus Philipsen highlighted that in a maturing County with an urban growth boundary, there are certain unavoidable trends: “open space becomes more and more threatened.” For NeighborSpace, responding to this challenge means conserving vacant land and underused parking lots and reimagining them as parks, gardens, trails, and other resources that have economic, social, and environmental value for the community.

Developing a Prioritization Model

In NeighborSpace’s early years, choosing sites to retrofit was largely reactive. Philipsen explained that Barbara Hopkins’ leadership was key to moving NeighborSpace toward a more proactive model of site selection that prioritized projects with multiple co-benefits. The reality is, NeighborSpace is a very small organization. While they have a very active board of directors and volunteer base, actual staffing time is extremely limited; their three staff members, including Hopkins, all work half-time. Minimal staff time, coupled with limited funding means that NeighborSpace needed to find a way to be strategic with project selection. To Philipsen, this meant asking “how can we, with these relatively small amounts of open space, be more effective?”

The answer was the development of an innovative Geographic Information System (GIS) model that enables NeighborSpace to prioritize land acquisition based on whether it will improve the social, economic, and/or environmental factors of livability. Their conservation model—developed in partnership with the National Park Service’s Rivers, Trails, and Conservation Assistance Program and other key stakeholders—is able to overlay a number of critical map layers including vacant parcels, impervious surfaces, open space access, vulnerable populations, poverty rates, property values, social priorities, and more to identify land that should be prioritized for conservation.

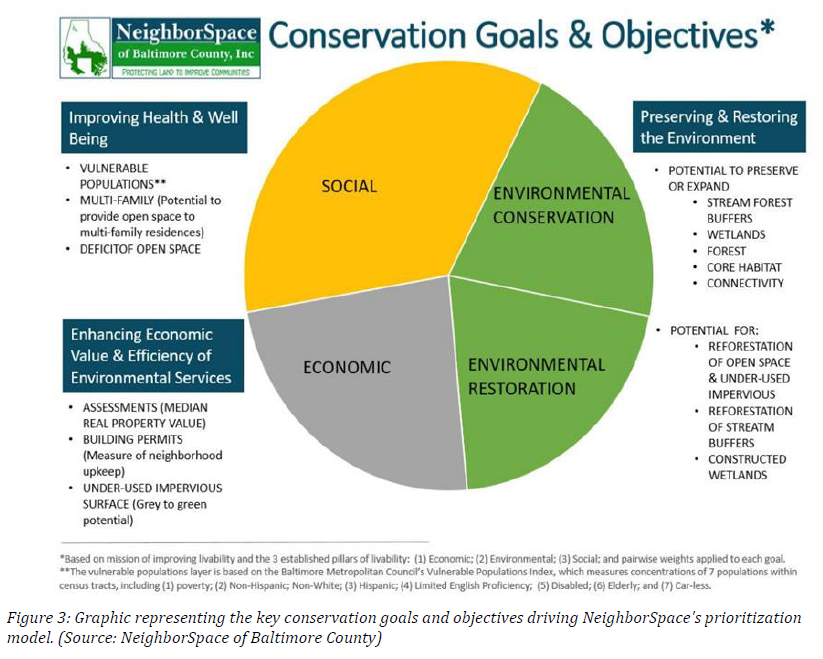

To ensure that the model can reflect community needs, NeighborSpace gathered stakeholder input to identify key conservation goals under their social (improving access to open space), environmental (preserving and restoring the environment), and economic (enhancing economic value) goals. Community members identified priority objectives including increased open space access for vulnerable populations and residents of multi-family residences, improved impervious surfaces, and more. After identifying key conservation goals and objectives, NeighborSpace partnered with experts at West Virginia University to conduct preference testing and a pairwise comparison to assign weights to these different conservation priorities based on community values.26 Figure 3 below provides a graphical representation of the final priority matrix, representing the weighted values identified by NeighborSpace’s constituents.

As a final step in rolling out their conservation model, NeighborSpace secured grant funding from Keep Maryland Blue and the Maryland Environmental Trust to conduct a third party evaluation of their tool. They also enlisted local GIS experts from the Chesapeake Conservancy to evaluate the model. After review, The Conservancy concluded that “the insights gleaned from this model provide a comprehensive perspective towards conserving and prioritizing open space in Baltimore County.”27 With efficacy confirmed, NeighborSpace had created a model that could be applied to any potential conservation project in order to rank it against three primary conservation goals.

Moreover, this model enabled NeighborSpace to strategically identify vacant land in Baltimore with the highest potential for improving livability across these three categories. “Underutilized impervious surface is the holy grail,” says Hopkins. “[With the GIS model], we can take all of the vacant plots in the County and rank them from best to worse in terms of conservation value.” This provides NeighborSpace with the data needed to develop a strategic conservation plan, information they hope to incorporate into the County’s 2030 Master Planning Process.

Furthermore, Hopkins chairs a group called the Baltimore County Green Alliance which includes watershed conservation non-profits, organizations doing natural history education, as well as environmental advocacy groups. In their strategic conservation plan, NeighborSpace hopes to leverage their conservation model to identify other opportunities for partnering with organizations in the Alliance to address watershed health and equity challenges within the region. “We don’t always think as expansively as we should about how land conservation can be a solution to these other challenges,” Hopkins explained. She noted that efforts of many watershed restoration organizations, for example, are hindered by a lack of land ownership, something that NeighborSpace could potentially help with. “We want to look at where more partnership opportunities can exist as we plan for the future.”

Working in Close Partnership with the County of Baltimore

While a close relationship with the County of Baltimore is foundational to NeighborSpace’s work in many ways, access to funding through the County’s local open space (LOS) waiver fees is absolutely essential. According to County law, developers must set aside 1,000 feet of open space for each newly constructed dwelling unit. When developers are unable to meet that requirement, they are allowed to seek a LOS waiver from the County and instead pay a fee in lieu of open space. Since 2004, the County has allocated a portion of those LOS waiver fees to NeighborSpace to support their conservation work. While the County Council first approved an allocation of up to 10 percent in 2004, that amount was increased up to 20 percent of all fees in 2013.28 In fiscal year 2018, the County collected nearly $600,000 in fees; NeighborSpace’s 20 percent cut makes up a substantial portion of their operating budget.

For Steve Lafferty, Baltimore County’s Chief Sustainability Officer, the allocation of these fees to NeighborSpace is a vote of confidence. “[This] was a commitment at the County level that NeighborSpace would be a strong partner.” Since the current County Administrator, Johnny Olszewski, took office in 2018, environmental quality and land preservation have become a larger priority for the County. This provides an opportunity for NeighborSpace to play a larger role in strategic conservation moving forward. According to NeighborSpace, this includes supporting the County’s goals to build vibrant communities through public facility improvement, develop enhanced land management practices, improve resilience of county infrastructure, and improve relationships between County government and communities.29

Following the Community’s Lead When asked about NeighborSpace’s philosophy for working with communities, Hopkin’s answer is simple: “The best relationships are built on a foundation of mutual trust; we want to put communities in the driver’s seat.” While developers are often viewed as extractive and the government involvement can feel like an imposition, NeighborSpace has the trust needed to work with community members to collaboratively reimagine vacant lots. Jack Leonard, NeighborSpace Board Member and Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at Morgan State University, highlighted that this commitment to prioritizing the needs of under-resourced communities allows NeighborSpace to be perceived as an “honest broker.”

Some park projects are initiated when a community member identifies a parcel within their community that they would like to see retrofitted and comes to NeighborSpace for assistance; other times, NeighborSpace has an opportunity to purchase a parcel within the community and will approach community members to gauge interest. While NeighborSpace is always thinking about the primary conservation values identified in their retrofitting model, the presence of a community group is absolutely essential for the long-term success and maintenance of the property. In fact, no NeighborSpace project moves forward unless there is a community partner willing to provide approximately $1,600 of cash or in-kind services to support stewardship costs each year.

Once a parcel and a community partner are identified, NeighborSpace will support ongoing community stewardship by developing a management plan for each property, purchasing liability insurance, and pursuing grants for future upgrades. If necessary, they can also guide the community through a design and planning process. They are able to do this through a partnership with Morgan State University’s Program in Landscape Architecture. “We always have a design studio and we are always looking for [projects] for the students to work on,” said Jack Leonard. Supporting the design of NeighborSpace’s pocket parks gives students the opportunity to not only practice running charrettes and responding to community feedback, but also to gain experience turning vacant lots into viable community spaces. “A lot of our students come to the program wanting to solve issues specific to urban areas; they’re very attuned to resources like small parks.”

Moreover, Morgan State University attracts many students from within the URDL, meaning students are able to apply regional context in their designs and work on park sites that they can come back and visit regularly. After the students collect input and prepare design options, community members are able to vote on the final design for their parks. One park that went through this process in partnership with NeighborSpace and Morgan State University is the Adelaide Bentley Park, named in honor of a community leader responsible for preventing the displacement of the historically African American neighborhood of East Towson. After community members—including Mrs. Bentley herself—voted on a plan for the space, NeighborSpace was able to secure $20,000 in funding from the County to implement the design.30 The park officially opened to the public in June 2017.

Results

To date, NeighborSpace has conserved 21 parcels with a total area of 100 acres throughout the URDL. A clear leader in Baltimore County, they are the only green space nonprofit within the URDL utilizing GIS modeling and conservation plans developed in partnership with residents and other key stakeholders. They are also the only non-profit receiving a portion of the County’s LOS waiver fees.

The revenue from LOS waiver fees—along with funding from individual donation and grants—has enabled NeighborSpace to make real change in communities throughout the URDL. At Ridgely Manor Park, the site of a Hess Oil gasoline leak, a new drainage system installed at the site coupled with the green infrastructure benefits of the park has made a notable difference for residents. Dale Cassidy, President of the Ridgely Manor Community Association noted that before the park was developed, the neighborhood’s storm drains would overflow in major rain events and residents could see and smell enzymes and pollutants—remnants of the gas leak—flowing down the street. Cassidy noted that this issue that has vastly improved since the park was completed. In addition to serving as a critical conservation buffer for the neighborhood, the park provides a source of recreation for more than 180 duplexes in the neighborhood. “Through combined efforts, it has developed into an inviting and purposeful space for those in the area,” said Cassidy. “On any given day, you find folks dropping by for lunch, kids utilizing the open space for football, soccer, or just tossing a ball around.”31

At the Cherry Heights Woodland Garden, NeighborSpace has been able to work with a 25-person community steering committee from the Overlea Community Association to highlight the history of racial discrimination in the URDL. Many community association leaders had been immersed in the community and its history over time, but it was not until the group reviewed the original site plans for their parcel that they realized that the redlining district boundary between Overlea—a historically white community—and Cherry Heights—a historically Black community—ran diagonally through their soon-to-be park site. Now, NeighborSpace is working with the Overlea Community Association and a landscape architect to design a path through the park to represent the historical boundary. The group has also enlisted the help of a local anthropologist to design signs for the park to tell the history of redlining and segregation in the Overlea and Cherry Heights communities throughout the twentieth century.

In addition to managing open space sites across the URDL, NeighborSpace has been an important advocate for open space protection at the County level. Renee Hamidi, Executive Director of the Manor Conservancy in nearby Howard County explains that Hopkins is a force within the region. “Her organization isn’t gigantic, but when she speaks, people pay attention… she is able to draw attention to the Baltimore County Government and what they could do, what they should do, and what they’re not yet doing.” One critical example can be seen in NeighborSpace’s successful effort to advocate for the removal of loopholes in County open space laws that allowed developers to count parking islands towards their open space requirements and private amenities such as rooftop pools as deductions from their waiver fees. This effectively diminishes the amount of publicly accessible recreational space that the open space laws are intended to encourage. In addition, a NeighborSpace analysis of public records found that, due to these loopholes, the County lost more than $1 million in open space fees between 2016 and 2019.32 Thanks to a coordinated effort by NeighborSpace and their partners, the Baltimore County Council unanimously passed Bill 37-19 in September 2019, eliminating many of these loopholes.

But there is still more to be done in order for NeighborSpace to reach their full potential, and they have big plans for 2021. In addition to working with the County to improve LOS waiver fee schedules and communication channels, they are making critical steps internally to solidify the volunteer base they rely on for ongoing maintenance of park sites. Their priorities for fiscal year 2021 include developing a stewardship model for training and engaging a core group of volunteers at their park sites as well as creating a strategic conservation plan in collaboration with community partners and County government. In addition, they hope that additional fundraising efforts will enable them to acquire more park sites and begin to improve the connectivity of their network in the coming years.

Analysis and Implications

The majority of best practices, resources, and funding related to land conservation are dedicated to rural and large landscape conservation, a reality that has driven many of NeighborSpace’s conservation strategies. “There are parallels to rural land trusts, but they are limited,” says Board President Klaus Philipsen. “We are taking this known toolbox and we are changing it.” For NeighborSpace, that means carving out their own space by applying the known concepts of land trusts to spaces as small as 0.2 or 0.15 acres, a strategy which he recognizes as unique, and at times, a leap.

“Our work is different from rural land trusts, which often get pristine parks,” highlighted Klaus. On the contrary, many of the parcels NeighborSpace takes on are “leftover” spaces that were unused, collecting garbage, or even the former site of a gasoline leak, as was the case of Ridgely Manor Park.33 Unlike many rural land trusts, NeighborSpace’s power doesn’t come from having a high value of acres—they currently manage 100 acres throughout the County—nor does it come from the direct environmental impacts of these park sites. Philipsen noted that while NeighborSpace’s 21 park sites may not be measurably changing the water quality of the Chesapeake—although the sites do provide important water filtration as green infrastructure sites. Their greatest impacts on climate change come through leveraging policy, promoting community engagement and education, and increasing awareness of the importance of open space for improving the local urban heat effects, water quality, air quality, and more. Echoing this, NeighborSpace Board Member Kathy Martin highlighted that one of the critical roles of urban land trusts is to help folks deal with and understand “what climate change means to their community.”

Understanding the value and co-benefits provided by urban conservation work is important for shifting funding and resources to support the work of land trusts like NeighborSpace. Jenn Aiosa, the Executive Director of Blue Water Baltimore, pointed out that an excellent opportunity for incentive-shifting comes from stormwater management. She noted that, while throughout the Baltimore region there is a major focus on improving water quality in the Chesapeake Bay, incentive programs are largely geared toward rural land and suburban lawns. Because yards and green spaces in urban areas are much smaller, many urban stormwater investments in Baltimore City and many parts of the URDL go toward street sweeping. While street sweeping does have benefits for sediment and nutrient reduction, such investments are, she reports, largely missing the mark.

“Something that Blue Water Baltimore has advocated for is a greater commitment to green stormwater as opposed to street sweeping,” said Aiosa. Green infrastructure investment gets to the root of the problem: mitigating the high volume of stormwater runoff, which is only increasing with climate change and development through the URDL. “In the name of stormwater infrastructure investment, you can create green spaces, you can create tree lined streets, you can calm traffic. You could get a lot of co-benefits, but we tend to look myopically at each of those needs.” Aiosa noted that by investing in green spaces and carefully designing for stormwater filtration and hydrology, NeighborSpace is able to have a more comprehensive approach to meeting both the County’s stormwater and green space needs.

This underscores a broader challenge: funding opportunities are limited for urban land trusts. Board Member Marsha McLaughlin noted that NeighborSpace has been actively reaching out to a larger funding pool by proactively, in their own grant writing, making the connections between green infrastructure investment and Chesapeake Bay restoration. While NeighborSpace has worked to improve their grant writing to highlight these co-benefits of their work, it seems that many private foundations throughout the region are also looking for opportunities to fund more creative solutions such as rain gardens, vegetated swales, and urban forest planting. This is a good trend in the private sector, yet NeighborSpace hopes that moving forward more State funding will go towards strategic stormwater management.

Lessons learned

NeighborSpace’s work highlights several key lessons learned for urban and suburban land conservation:

Language Matters

Jen Aiosa, Executive Director of Blue Water Baltimore and member of the Baltimore County Green Alliance, explained that in the greater Baltimore area, there is often a mindset that green spaces, parks, and other environmental protections are a second-tier priority. One of the areas where Aiosa says that NeighborSpace has been able to shine is in reminding residents and decision-makers that these resources should not be a luxury. This means meeting community members where they are. Aiosa noted that many urban land trusts discuss benefits in terms of stormwater runoff and nutrient reduction, issues that don’t resonate with community priorities. “This type of communication has led to a lot of missed opportunities,” Aiosa laments. In many Black and Latinx communities throughout the URDL, redlining and historical disinvestment have contributed to low tree canopy cover and high levels of air pollution. “If a resident is concerned about disinvestment in their community, in their health, and in their children’s health, then how do we speak in those terms?”

Strong Community Partnerships are Key

The success of urban and suburban land conservation is built on a foundation of community partnerships. In NeighborSpace’s case, not only do community organizations maintain the park sites and coordinate volunteers, but they have the ability to make these spaces important pieces of the community fabric. “Had we not had a core group of people—about 8 in our case—who were committed to ensuring the success of the park, this would have been impossible,” said Aaron Barnett of Powhatan Park. “You have to have people who are dedicated to the preservation of their community; they need to be there through thick and thin.” While NeighborSpace can provide critical support, community-based organizations shepherd these parks forward over time. Baltimore County’s Steve Lafferty notes that this requires land trust board members and staff members who understand community organizing. “You need to understand the community’s needs and work from the bottom up…it’s an iterative process.”

Utilize Multiple Platforms for Outreach and Engagement

While the success of pocket parks relies on the strength of community groups, the success of community groups relies on the strength of communication and outreach. Particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, the face-to-face interactions and casual conversations that drove many NeighborSpace partner organizations are less accessible, and organizations are being forced to rethink their communication and volunteer engagement strategies. To make communication more accessible in an increasingly virtual world, NeighborSpace secured a grant to develop a project called Portals for Our Partners (POP), which will create websites for all park sites. While NeighborSpace will maintain the URLs to ensure continuity, community associations will be able to host important information about their sites, volunteer opportunities, community needs, meeting times, and more in a centralized location. In addition to custom URLs, all community partners will also receive marketing materials, and training.34

Leverage Local and Regional Partners

One of the major opportunities of urban land conservation is the opportunity to leverage diverse regional partners. Universities can provide technical assistance—such as in the case of the Morgan State University’s Landscape Architecture Program—as well as critical volunteers support. Local landscaping businesses have donated materials or discounted services to many NeighborSpace park sites within their communities, while local non-profits—through the Baltimore County Green Alliance—work with NeighborSpace to collaborate on regional conservation priorities and advocacy related to open space. The County provides funding through their open space fees, opportunities for leveraging additional public private partnerships, and more. Partnerships provide opportunities to share responsibility and information, as well as a chance for diverse parties to work together to bring about the changes they wish to see in their communities.

Prioritize Youth Engagement Several of Neighbor

Space’s community partners highlighted the importance of youth engagement and environmental education to their ongoing park efforts. For Aaron Barnett of Powhatan Park, this means creating regular opportunities for the individuals in his youth mentoring program to do hands-on projects in the park. The children—aged 8 through 18—regularly participate in planting, maintenance, and other educational programs within the garden. When kids volunteer in their neighborhood, “it gives them a sense of pride and responsibility.” Martin Nibali of the Cherry Heights Woodland Garden echoed Barnett’s sentiments. A scout leader, Nibali found ways to get the young folks in his charge to get dirt under their fingernails. “The scouts really wanted to be focused on service,” he noted, and the garden was an accessible option in many ways. Furthermore, providing opportunities for youth to get involved in open space projects helps build long-term awareness of and support for green spaces within communities.

Policy Recommendations

Policymakers hoping to support urban and suburban land conservation efforts should consider the following.

Prioritize Local Open Space Waiver Fees

According to Baltimore County law, developers have the option to provide 1,000 feet of open space for each newly constructed dwelling unit or pay a LOS waiver from the County. According to Hopkins, many developers choose to do offsite open space improvements as opposed to paying the open space fee waiver. While this succeeds in making basic open space improvements, these developer-driven projects are often standalone and fail to meet regional strategic conservation goals such as choosing sites that prioritize vulnerable communities, have additional environmental benefits, or increase the connectivity of the open space network. If developers choose to provide offsite open spaces, existing relationships and regional context should be leveraged in order to maximize benefits. This means partnering with organizations like NeighborSpace that are carefully tracking the strategic needs of the community. If a developer is unable or unwilling to coordinate with community groups, NeighborSpace recommends that LOS waiver fees be prioritized so that municipal agencies and key partners can apply those funds to projects with the highest potential for improving livability.

Remove Loopholes in Local Open Space Requirements and Waiver Fees

Developing consistent funding streams is critical for sustaining urban conservation work. LOS waiver fees can serve as an important funding source, but loopholes often erode these funds. Loopholes that allow parking islands to count towards open space minimums or private amenities to reduce LOS waiver fees undermine the goal of these regulations: to provide public recreation space or funding for public open space projects. Removing loopholes is essential for maintaining this important funding stream. NeighborSpace Board President, Klaus Philipsen underscored that in addition to updating requirements, municipalities should strive to maintain high levels of transparency to ensure clear expectations are set for municipalities, non-profit partners, and developers alike.

Utilize Stormwater Fees

Stormwater fees help municipalities pay for ongoing stormwater management costs by collecting a fee from property owners based on the amount of impervious cover a property contains. This fee treats stormwater as a public utility of sorts; the more stormwater runoff a property generates—assuming that roofs, driveways, parking lots, and the like contribute to runoff—the more that property will pay for maintaining the stormwater infrastructure.35 These fees can provide an incentive for retrofitting underutilized impervious surfaces while simultaneously providing a funding stream for stormwater infrastructure maintenance and green infrastructure development.

Prioritize Investments with Social and Environmental Co-Benefits

When discussing municipal funding decisions, numerous interviewees stressed the need to prioritize solutions that have co-benefits. For example, many counties in the greater Baltimore area prioritize street sweeping – an activity with few co-benefits — as a stormwater management tool. In contrast, green infrastructure investments such as bioswales and green spaces help to manage stormwater and have multiple social and economic co-benefits for communities. Public dollars are limited, and opportunities to support multiple needs should be prioritized when possible.

About the Author

Kristen Wraithwall is a research consultant to the Lincoln Institute, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA and a Master of Environmental Management Candidate at the Yale School of the Environment. Wraithwall focuses on the intersections of urbanization, land use change, and food systems and is interested in the role that land conservation can play in building local community resilience. She has worked on land use policy with municipalities in California, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Wraithwall is a graduate of Harvard University.

Appendix 1: Study Group Questions

One of the several uses of this case profile is in an academic setting. Following are several questions that an instructor can pose to their study group to engage participants in the details of the narrative.

- Is this a novel initiative? How have the protagonists creatively addressed the challenges to protecting green spaces in highly developed urban and suburban areas?

- Is the solution profiled in this case measurably effective and strategically significant for the practice of land and biodiversity conservation and climate change adaptation and mitigation? Why and why not?

- Is the solution emerging from this case transferable to other jurisdictions and will it endure?

- Is this a large landscape solution that crosses sectors and political jurisdictions? Who are the key players from various sectors essential to the success of this initiative? What are the key technologies and organizational methodologies?

- If you were manager of Neighborspace’s urban land conservation and retrofitting project, what would be your priorities for action in the next year? Over the next ten years?

References

1. Foley JA, DeFries R, Asner GP, Barford C, Bonan G, Carpenter SR, et al. Global consequences of land use. Science. 2005; 309: 570–574. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1111772 PMID: 16040698

2. IPBES. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science- Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Brondizio E. S., Settele J, D´ıaz S, Ngo HT, editors. Bonn, Germany: IPBES Secretariat; 2019. Available: https://www.ipbes.net/global-assessment-report-biodiversity-ecosystem-services.

3. Pimentel D, Stachow U, Takacs DA, Brubaker HW, Dumas AR, Meaney JJ, et al. Conserving biological diversity in agricultural/forestry systems: most biological diversity exists in human-managed ecosystems. Bioscience. 1992; 42: 354–362.

4. Venter O, Fuller R a., Segan DB, Carwardine J, Brooks T, Butchart SHM, et al. Targeting global protected area expansion for imperiled biodiversity. PLoS Biol. 2014; 12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001891 PMID: 24960185

5. Ceballos G, Garcı´a A, Ehrlich PR. The sixth extinction crisis: loss of animal populations and species. J Cosmol. 2010; 8: 1821–1831.

6. Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR, Dirzo R. Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017; 114: E6089–E6096. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1704949114 PMID: 28696295

7. Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR, Barnosky AD, Garc´ıa A, Pringle RM, Palmer TM. Accelerated modern human- induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci Adv. 2015; 1: 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1400253 PMID: 26601195

8. Rockstro¨ m J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson Å, Chapin F. Stuart III, Lambin EF, et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature. 2009; 46: 472–475. https://doi.org/10.1038/461472a PMID: 19779433

9. Curtis PG, Slay CM, Harris NL, Tyukavina A, Hansen MC. Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Sci- ence. 2018; 361: 1108–1111. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau3445 PMID: 30213911

10. Rehbein JA, Watson JEM, Lane JL, Sonter LJ, Venter O, Atkinson SC, et al. Renewable energy development threatens many globally important biodiversity areas. Glob Chang Biol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15067 PMID: 32133726

11. Boyd C, Brooks TM, Butchart SHM, Edgar GJ, Da Fonseca G a B, Hawkins F, et al. Spatial scale and the conservation of threatened species. Conserv Lett. 2008; 1: 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2008.00002.x

12. Washitani I. Traditional sustainable ecosystem “SATOYAMA” and biodiversity crisis in Japan: conservation ecological perspective. Glob Environ Res. 2001; 5: 119–133.

13. Kato M. “SATOYAMA” and biodiversity Conservation: “SATOYAMA” as important insect habitats. Glob Environ Res. 2001; 5: 135–149.

14. Takeuchi K, Brown RD, Washitani I, Tsunekawa A, Yokohari M, editors. Satoyama: the traditional rural landscape of Japan. Tokyo: Springer; 2003. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-67861-8

15. Takeuchi K, Ichikawa K, Elmqvist T. Satoyama landscape as social-ecological system: Historical changes and future perspective. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 2016; 19: 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.11.001

16. Belair C, Ichikawa K, Wong BYL, Mulongoy KJ, editors. Sustainable use of biological diversity in socio-ecological production landscapes (CBD Technical Series No. 52). Montreal, Canada: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity; 2010. Available: https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-52-en.pdf.

17. IPSI Secretariat. IPSI Handbook: International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI) charter, operational guidelines, strategy, plan of action 2013–2018. Tokyo: United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS); 2015. Available: https://satoyama-initiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IPSI-Handbook-web.pdf.

18. Kadoya T, Washitani I. The Satoyama Index: a biodiversity indicator for agricultural landscapes. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2011; 140: 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2010.11.007

19. Tieskens KF, Schulp CJE, Levers C, Lieskovsky´ J, Kuemmerle T, Plieninger T, et al. Characterizing European cultural landscapes: accounting for structure, management intensity and value of agricultural and forest landscapes. Land use policy. 2017; 62: 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.12. 001

20. Convention on Biological Diversity. Decision 14/8: Protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures. 2018. Available: https://www.cbd.int/conferences/2018/cop-14/documents.

21. Allan JR, Watson JEM, Di Marco M, O’Bryan CJ, Possingham HP, Atkinson SC, et al. Hotspots of human impact on threatened terrestrial vertebrates. PLoS Biol. 2019; 17: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000158 PMID: 30860989

22. Kennedy CM, Oakleaf JR, Theobald DM, Baruch-Mordo S, Kiesecker J. Managing the middle: a shift in conservation priorities based on the global human modification gradient. Glob Chang Biol. 2019; 25: 811–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14549 PMID: 30629311

23. Brooks TM, Mittermeier RA, Da Fonseca GAB, Gerlach J, Hoffmann M, Lamoreux JF, et al. Global bio- diversity conservation priorities. Science. 2006; 313: 58–61. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127609

PMID: 16825561

24. Dinerstein E, Vynne C, Sala E, Joshi AR, Fernando S, Lovejoy TE, et al. A global deal for nature: guiding principles, milestones, and targets. Sci Adv. 2019; 5: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw2869 PMID: 31016243

25. Hannah L, Roehrdanz PR, Marquet PA, Enquist BJ, Midgley G, Foden W, et al. 30% land conservation and climate action reduces tropical extinction risk by more than 50%. Ecography. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04902 PMID: 33304029

26. Goldstein A, Turner WR, Spawn SA, Anderson-teixeira KJ, Cook-patton S, Fargione J, et al. Protecting irrecoverable carbon in Earth’s ecosystems. Nat Clim Chang. 2020; 10: 287–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0738-8

27. UNU-IAS, IGES, editors. Sustainable use of biodiversity in socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS) and its contribution to effective area-based conservation (Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 4). Tokyo: United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability; 2018. Available: http://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:6636/SITR_vol4_fullset_FINAL_web.pdf.

28. Subramanian Suneetha M., Yiu E, Leimona B. Enhancing effective area-based conservation through the sustainable use of biodiversity in socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS). In: UNU-IAS, IGES, editors. Sustainable use of biodiversity in socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes and its contribution to effective area-based conservation (Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol 4). Tokyo: United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability; 2018. pp. 1–13. Available: http://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:6636/SITR_vol4_fullset_FINAL_web.pdf.

29. Imai J, Kadoya T, Washitani I. A land-cover heterogeneity index for the state of biodiversity in the Satoyama landscape: assessment of spatial scale and resolution using participatory monitoring data in Fukui Prefecture. Japanese J Conserv Ecol. 2013; 18: 19–31. https://doi.org/10.18960/hozen.18.1_19 Japanese.

30. Yoshioka A, Kadoya T, Imai J, Washitani I. Overview of land-use patterns in the Japanese archipelago using biodiversity-conscious land-use classifications and a Satoyama index. Japanese J Conserv Ecol. 2013; 18: 141–156. https://doi.org/10.18960/hozen.18.2_141. Japanese.

31. Yoshioka A, Fukasawa K, Mishima Y, Sasaki K, Kadoya T. Ecological dissimilarity among land-use/ land-cover types improves a heterogeneity index for predicting biodiversity in agricultural landscapes. Ambio. 2017; 46: 894–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0925-7 PMID: 28573598

32. Kobayashi T, Tateishi R, Alsaaideh B, Sharma RC, Wakaizumi T, Miyamoto D, et al. Production of Global Land Cover Data–GLCNMO2013. J Geogr Geol. 2017; 9: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5539/jgg.v9n3p1

33. Gregorio A Di, Jansen LJM. Land cover classification system (LCCS): classification concepts and user manual. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; 2000. Available: http://www.fao.org/3/x0596e/x0596e00.htm.

34. Mittermeier RA, Gil PR, Hoffman P, Pilgrim J, Brooks T, Mittermeier CG, et al. Hotspots rvisited: Earth’s biologically richest and most endangered ecoregions. Mexico City: CEMEX; 2004.

35. Eken G, Bennun L, Brooks TM, Darwall W, Fishpool LDC, Foster M, et al. Key biodiversity areas as site conservation targets. Bioscience. 2004; 54: 1110–1118. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[1110:KBAASC]2.0.CO;2.

36. Langhammer PF, Bakarr MI, Bennun LA, Brooks TM, Clay RP, Darwall W, et al. Identification and gap analysis of key biodiversity areas: targets for comprehensive protected area systems. Gland, Switzer- land: IUCN; 2007. Available: http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/pag_015.pdf.

37. Foster MN, Brooks TM, Cuttelod A, De Silva N, Fishpool LDC, Radford EA, et al. The identification of site of biodiversity conservation significance: progress with the application of a global standard. J Threat Taxa. 2012; 4: 2733–2744. https://doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o3079.2733-44.

38. Birdlife International. World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas. Developed by the KBA Partnership; 2017. Available: www.keybiodiversityareas.org.

39. Heinimann A, Mertz O, Frolking S, Christensen AE, Hurni K, Sedano F, et al. A global view of shifting cultivation: recent, current, and future extent. PLoS One. 2017; 12: 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184479 PMID: 28886132

40. Kintisch E. Improved monitoring of rainforests helps pierce haze of deforestation. Science. 2007; 316: 536–537. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.316.5824.536 PMID: 17463263

41. Pe´rez-Hoyos A, Rembold F, Kerdiles H, Gallego J. Comparison of global land cover datasets for crop- land monitoring. Remote Sens. 2017; 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9111118

42. Tateishi R, Uriyangqai B, Al-Bilbisi H, Ghar MA, Tsend-Ayush J, Kobayashi T, et al. Production of global land cover data—GLCNMO. Int J Digit Earth. 2011; 4: 22–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538941003777521

43. Tateishi R, Hoan NT, Kobayashi T, Alsaaideh B, Tana G, Phong DX. Production of global land cover data–GLCNMO2008. J Geogr Geol. 2014; 6: 99–122. https://doi.org/10.5539/jgg.v6n3p99

44. Fritz S, See L, Mccallum I, You L, Bun A, Moltchanova E, et al. Mapping global cropland and field size. Glob Chang Biol. 2015; 21: 1980–1992. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12838 PMID: 25640302

45. Samberg LH, Gerber JS, Ramankutty N, Herrero M, West PC. Subnational distribution of average farm size and smallholder contributions to global food production. Environ Res Lett. 2016; 11: 124010. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/12/124010

46. Landis DA. Designing agricultural landscapes for biodiversity-based ecosystem services. Basic Appl Ecol. 2017; 18: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2016.07.005

47. United Nations General Assembly. United Nations Decade of Family Farming (2019–2028). United Nations General Assembly; 2017. Available: https://undocs.org/A/RES/72/239.

48. Queiroz C, Beilin R, Folke C, Lindborg R. Farmland abandonment: Threat or opportunity for biodiversity conservation? A global review. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. Ecological Society of Amer- ica; 2014. pp. 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1890/120348

49. Redlich S, Martin EA, Wende B, Steffan-Dewenter I. Landscape heterogeneity rather than crop diversity mediates bird diversity in agricultural landscapes. PLoS One. 2018; 13: 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200438 PMID: 30067851

50. Hass AL, Kormann UG, Tscharntke T, Clough Y, Baillod AB, Sirami C, et al. Landscape configurational heterogeneity by small-scale agriculture, not crop diversity, maintains pollinators and plant reproduction in western Europe. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2018; 285: 20172242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.2242.

51. Martin AE, Collins SJ, Crowe S, Girard J, Naujokaitis-Lewis I, Smith AC, et al. Effects of farmland heterogeneity on biodiversity are similar to—or even larger than—the effects of farming practices. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2020; 288: 106698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.106698

52. Sirami C, Gross N, Baillod AB, Bertrand C, Carrie´ R, Hass A, et al. Increasing crop heterogeneity enhances multitrophic diversity across agricultural regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019; 116: 16442–16447. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1906419116 PMID: 31358630

53. Natori Y, Silbernagel J, Adams MS. Biodiversity conservation planning in rural landscapes in Japan: integration of ecological and visual perspectives. In: Pavlinov I, editor. Research in biodiversity: models and applications. InTech; 2011. pp. 285–306. https://doi.org/10.5772/23645

54. Argumedo A, Wong BYL. The ayllu system of the Potato Park (Peru). In: Belair C, Ichikawa K, Wong BYL, Mulongoy KJ, editors. Sustainable use of biological diversity in socio-ecological production landscapes in socio-ecological production landscapes (CBD Technical Series no 52). Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity; 2010. pp. 84–90. Available: https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-52-en.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X10000040 PMID: 20137104

55. San Vicente Tello A, Jo¨ nsson M. Landrace maize diversity in milpa: a socio-ecological production landscape in Soteapan, Santa Marta Mountains, Veracruz, Mexico. In: UNU-IAS, IGES, editors. Understanding the multiple values associated with sustainable use in socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol 5). Tokyo: United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS); 2019. pp. 73–84. Available: https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:7506/SITR_vol5_fullset_web.pdf.

56. Raygorodetsky G. The archipelago of hope: wisdom and resilience from the edge of climate change. New York: Pegasus Books; 2017.

57. Peck S. Planning for Biodiversity: Issues and Examples. Washington, DC: Island Press; 1998.

Endonotes

1 City of Baltimore. “History of Baltimore.”

2 Puentes and Orfield. “Valuing America’s First Suburbs: A Policy Agenda for Older Suburbs in the Midwest.”

3 NeighborSpace. “About.”

4 NeighborSpace. “About.”

5 Watsky, Rachel. 2018.

6 NeighborSpace. “About.”

7 Wilson, Bev. 2020.

8 Rowland-Shea et al. 2020.

9 Herrington, Susan. 2010.

10 Baltimore County Government. “PDF Map Library – Baltimore County.”

11 NeighborSpace. “About.”

12 Neighborspace. “Facts about the Organization.”

13 Rowland-Shea et al. 2020.

14 Lakhani, Nina. 2020.

15 NeighborSpace of Baltimore County. “About.”

16 Neighborspace. “Facts about the Organization.”

17 Feeding America. “Child Hunger & Poverty in Baltimore County, Maryland | Map the Meal Gap.”

18 Jennings and Bamkole, 2019.

19 Carter and Campbell, 2015.

20 Jennings and Bamkole, 2019.

21 Rowland-Shea et al. 2020.

22 Kleinschroth and Kowarik, 2020.

23 Cinderby, 2020.

24 Dunham-Jones and Williamson. 2008.

25 NeighborSpace of Baltimore County. “About.”

26 Hopkins, 2018.

27 Hopkins, 2018.

28 Sears, 2013.

29 Hopkins, 2020a.

30 Pacella, 2016.

31 Hopkins, 2019.

32 Knezevich, 2019.

33 Perl, 2014.

34 Hopkins, 2020b

35 Yencha, 2020.

The original paper of this case study can be found here.