Building and Supporting Resilient Biocultural Territories in the Face of Climate Change

27.02.2012

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

Indigenous People’s Biocultural Climate Change Assessment Initiative (IPCCA)

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

27/02/2012

-

REGION :

-

Global

-

SUMMARY :

-

The IPCCA is an indigenous initiative which brings together indigenous communities and organizations from a diversity of fragile and biodiverse ecosystems and socio-ecological production landscapes to assess the impacts of climate change and build responses that enable continued resilience and strengthen a harmonious relationship between people and nature. This case study explores the IPCCA approach of indigenous biocultural territories and a methodology based on combining traditional knowledge, local inquiry and science through a mutli-stakeholder participatory process to understand climatic change as it is experienced locally, assess climatic and ecosystem conditions and trends and build adaptive responses for well-being. The IPCCA approach is offered as a vehicle for accomplishing the Satoyama Initiative goals.

-

KEYWORD :

-

indigenous biocultural territories, climate change, traditional knowledge, livelihoods, well-being

-

AUTHOR:

-

J. Marina Apgar Marina’s main research interests are in collective processes for endogenous development in times of global change, stemming from years of experience working in action research projects in Latin America with indigenous and non-indigenous communities. She has a Human Ecology PhD in adaptive and endogenous development of Kuna Yala: an indigenous biocultural system and is currently employed as Research and Knowledge Management Officer at the IPCCA Secretariat house in Asociación ANDES in Cusco, Peru.

I. Introduction

Socio-ecological production landscapes, or Satoyama-like landscapes are the product of historical co-evolutionary relationships between communities and ecosystems. Most indigenous peoples have historically maintained harmonious relationships within their territories, nurturing the rich biological and cultural diversity found in the world. Today, indigenous peoples are among the most impacted by climate change (UNPFII, 2007). Their landscapes and territories are facing severe impacts of extreme weather events such as droughts or hurricanes, and melting of the permafrost and glaciers and sea level rise as a result of rising temperatures, leading in some cases to relocation of entire communities and in most cases to a weakened ability to sustain livelihoods and well-being and maintain the co-evolutionary relationship with the ecosystems that have enabled their historical resilience. The Indigenous Peoples’ Biocultural Climate Change Assessment (IPCCA) initiative is a response to this challenge, empowering indigenous communities to undertake local analysis of the changes and their impacts in order to build appropriate adaptation and mitigation responses that strengthen their socio-ecological systems and enable well-being within their territories.

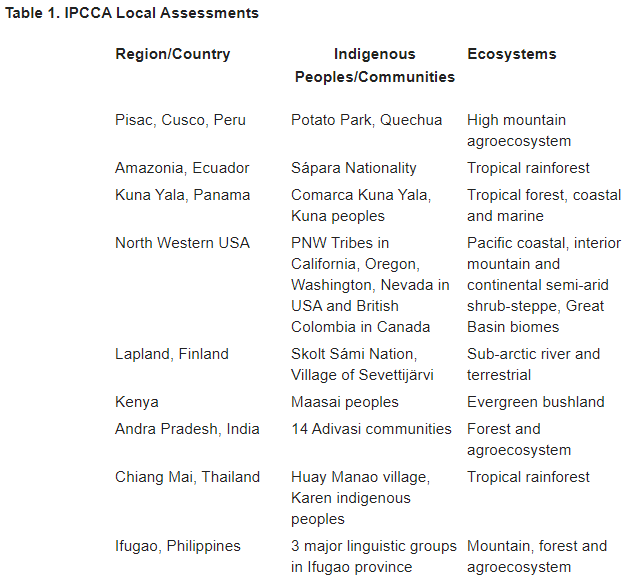

Based on the experience of indigenous communities, the IPCCA uses a biocultural response, empowering communities in their indigenous models of territoriality. Since its inception in 2009, nine local biocultural assessments of climate change impacts are being implemented, as seen in Table 1 the local assessments were selected to provide diverse experiences of the impacts of changing climates on ecosystems and livelihoods.

The local assessments use local frameworks and perceptions of climate and its changes to build understanding of the changes induced on the ecosystem-community relationships and their impacts on livelihoods and well-being. Through building epistemological bridges between traditional knowledge and science, new innovative approaches to maintaining livelihoods are empowering communities to strengthen and reclaim their territorial approaches within the current challenging context of global change. This case study illustrates how the IPCCA approach and methodology are appropriate vehicles for addressing the goals embraced by the Satoyama Initiative to maintain harmonious relationships between nature and people for resilient socio-ecological production landscapes.

II. Indigenous Biocultural Territories

Indigenous biocultural territories is a proposal for territorial management modeled on traditional indigenous territoriality (Argumedo & Pimbert, 2008). The term biocultural is used to emphasize the interlinked nature of the social and environmental systems, as well as providing a platform for recognition of the biocultural heritage contained within the territory (Swiderska, 2006). Elements of territoriality include land tenure and use, ritual practices relating to the land, systems of production and exchange, political claims and cultural identity (Liffman, 1998). Examples of traditional models include the Comarca system in Panama, ejidos in Mexico and the ayllu system in the Andes. A common element of these systems is the resilient and agrobiodiverse landscapes that are found within them. While each model developed within a particular local context of ecosystems and culture, they all share a common holistic approach to managing the relationships between people and living spaces. The resulting territories and their landscapes are therefore the product of historical engagement in a particular way with the world and the process of adapting to their environmental conditions and climate (Ford et. al 2006; Posey, 2001; Stevens & De Lacy, 1997).

Photo 1. The Potato Park landscape, Pisaq, Cusco, Peru. (Photo by ANDES)

Besides being grounded in territory and indigenous governance, processes used by indigenous people to manage land and life are also rooted in an indigenous understanding of the cosmos, in which people and all other beings in the world are interconnected, creating social relations and obligations between all beings (Berkes 1999, International Council for Science 2002, Allen et al. 2009). The resources and biodiversity found in indigenous territories are managed through a reciprocal relationship between all beings. Indigenous resource management practices are therefore the result of a way of being in the world, the consequence of which, in many cases, has been to nurture resilient social and ecological systems and landscapes.

Photo 2. Ahin Ricefields, Ahin, Tinoc, Philippines. (Photo by TEBTABBA)

This territorial approach to understanding development and maintenance of socio-ecological production landscapes provides a wide base for strengthening resilience. Processes that have maintained resilience in these particular socio-ecological production landscapes include social organisation, spiritual engagement, economic relations, knowledge production and sharing, and collective governance. In many cases these underlying processes and the associated knowledge have been degraded through colonization and continued discrimination as well as new threats such as climate change. The indigenous biocultural territories approach used by the IPCCA provides an opportunity to creatively build upon traditional territorial models in order to create systems that can respond to the current political, environmental and social contexts and challenges. Through assessing where impacts are impairing the ability of communities to maintain or strengthen their resilience, new innovative models are built. Socio-ecological production landscapes in this context are both a vehicle for resilience and the product of historical resilience.

III. The IPCCA Methodology

In undertaking biocultural climate change assessments, the IPCCA has built upon the experiences of local partners working in diverse and fragile ecosystems across the world, to develop a common methodology. The methodological framework used is based on intercultural dialogue, bringing together participatory, emancipatory and indigenous methods adapted to the local context in a multi-stakeholder collaborative process.

Political, economic, and ecological processes are at play in creating climate change and solutions must therefore address all of these aspects. The processes that are drivers of climate change occur across physical parts of the globe and its cultural spheres, such as global production and consumption patterns that are responsible for greenhouse gas emissions; hence it is understood not just as climate change but as global change (Karl & Trenberth, 2003). It follows, therefore, that adaptive strategies for responding to global change must create links between the scales and cultural contexts that create the changes and those that are being impacted. Intercultural practice is a way of doing this, which allows awareness and analysis of the inequalities embedded in interactions between indigenous societies and their knowledge systems and dominant cultures. This is particularly important in the IPCCA process, as indigenous peoples are the most vulnerable due to historic process of discrimination and their direct dependence on the ecosystems they inhabit.

Photo 3. IPCCA Local Assessment member participating in a methodologies workshop in Kuna Yala, Panama (Photo by Gleb Raygorodetsky)

The first step in the process involves developing the structures that will be used to undertake the analysis – a local steering committee is established, and study and focus groups identified for undertaking analysis of climate change and its impacts in the communities. Once the structures are in place, a baseline is developed. Information is gathered to build a picture of the current state of the biocultural territory (ecosystems, communities etc.) and climatic conditions in the area. Strong emphasis is placed on recovering traditional knowledge on ecosystems and climate. Ecosystems services are described from a local perspective, valuing the rich knowledge of biodiversity and climate that is the product of their co-evolutionary past. In some cases this requires recovery of knowledge from elders, and intergenerational exchange is a key element in this process of empowerment.

Photo 4. Identifying the Sápara hunting and gathering seasons in the Sápara Territory, Ecuador (Photo by Marina Apgar)

Photo 5. Analysis of the IPCCA Conceptual Framework in the Potato Park, Peru (Photo by ANDES)

Once a clear picture of the current state of the biocultural territory and climatic conditions is achieved, an assessment of conditions and trends and their impact on the identified elements of resilience in socio-ecological production landscapes is undertaken. Through use of cutting edge tools such as global climate models brought together with maps of traditional landscape management practices, bridging of epistemologies enables analysis of potential future scenarios for a resilient landscape that can provide well-being. The carrying capacity and resource use within the landscape is based on historical use and knowledge for landscape regeneration taking into consideration the changing conditions. The resulting information is used to undertake futuring activities and scenario building exercises within collective decision making processes for future planning.

Throughout all stages of the assessment, maximum participation of community groups and members is ensured through a collaborative process. As the assessment is driven by the community, local authorities and decision making spaces provide participatory platforms, ensuring that all relevant knowledge and expertise of aspects of landscape management, livelihoods practices as well as spiritual connections are contributing to building a picture of the challenges and finding avenues for responding appropriately.

IV. Building Resilient Biocultural Territories

The strategic goal of the IPCCA local assessments is the development of evidence-based and locally appropriate responses that enable resilience of the biocultural territory in the face of climate change. To this end, each indigenous biocultural territory undertaking a local assessment develops life plans. Life plans are strategies for cultural, social, political and economic affirmation of a territorial approach to development – they are, in essence, development plans that focus on building resilience and ensuring well-being. They are built from within, creating strategies to use local knowledge, values and objectives to build resilient production landscapes to face climate change and other political, economic and social challenges.

The life plans developed through the IPCCA assessment process are vehicles for reaching the Satoyama Initiative vision of realizing societies in harmony with nature. Developed from a holistic biocultural understanding of territory, landscape, ecosystems, knowledge and collective life, the IPCCA assessments can: consolidate wisdom on securing diverse ecosystem services and values; integrate traditional ecological knowledge and modern science to promote innovations; and explore new forms of co-management systems while respecting traditional communal land tenure.

An example of how this may be accomplished comes from the Sápara territory in the Ecuadorian Amazon. In the Amazon, climate change is impacting on hunting and gathering practices, which are the basis of Sápara livelihoods. The communities are responding through analyzing climatic conditions and trends and their impacts on forest ecosystems that provide services ranging from provisioning (food, fuel, water etc.) to cultural (spiritual connection to the forest). An understanding of climate change as a global process through scientific models provides opportunity to link local to global concerns. The vast knowledge of the forest ecosystems, which is based on a historical co-evolutionary relationship, is combined with GIS maps to identify areas of vulnerability from various threats, including those posed by oil exploration in their territory. Their life plan, which is in development, will address the need to adjust livelihoods practices while needing to secure their communal land tenure to ensure their ecosystem services and resilience in their territory. The territorial approach enables a wide view of the local needs, without separating environmental and social realities.

Photo 6. Sápara hunting practices. (Photo by ANDES).

A different example comes from the subarctic tundra ecosystems in Lapland, Finland. The Skolt Sámi practice their traditional reindeer herding and subsistence fishing activities in a biocultural territory that is experiencing severe impacts of climate change. The changes being experienced illustrate that climatic change combines with other social and economic processes and is threatening their reindeer herding livelihoods. The relationship of people and reindeer is a deep and spiritual connection and the impacts on culture and spirituality cannot be underestimated. Through forced relocation Sámi knowledge has been significantly degraded and livelihood adaptations were made from nomadic to settled life. Today, through the IPCCA local assessment the Skolt Sámi are recovering much of their lost traditional knowledge and practices, to strengthen their own understanding of historical resilience and to renew their practices of subsistence fishing and reindeer herding. Use of video techniques and GIS are assisting in the assessment and development of adaptation plans that can maintain the harmonious relationship between people and nature, which is the basis for resilience.

Photo 7. Reindeer attempting to reach fodder bellow snow and ice in Sámi territory, Finland. (Photo by Snowchange)

The two examples illustrate that each biocultural territory is different, and each must be understood through local frameworks and processes. The International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative is a network of initiatives, organizations and communities all contributing into the complex task of maintaining resilient socio-ecological production landscapes. The IPCCA territorial and methodological approach provides opportunity for empowering communities to recreate their futures based on what has worked in the past and what is needed to face new challenges.

V. References

Alejandro, A., Pimbert, M., 2008. Protecting farmer’s rights with Indigenous Biocultural Heritage Territories: The experience of the Potato Park. IIED.

Allen, W.J., Ataria, J.M., Apgar, J.M. Harmsworth, G., and Tremblay, L.A., 2009. Kia pono te mahi putaiao — Doing science in the right spirit. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand [online], 39 (4), 239–242. Available from: http://learningforsustainability.net/pubs/DoingScienceInTheRightSpirit.pdf.

Berkes, F., 1999. Sacred ecology: Traditional ecological knowledge and resource management. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis.

Ford, J. D., Smit, B., Wandel, J., & MacDonald, J., 2006. Vulnerability to climate change in Igloolik, Nunavut: what we can learn from the past and present. Polar Record, 42(221), 127-138.

International Council for Science, 2002. Traditional knowledge and sustainable development. ICSU & UNESCO.

Karl, T. R., Trenberth, K. E., 2003. Modern Climate Change. Science, 302(5651), 1719 – 1723.

Liffman, P., 1998. Indigenous Territorialities in Mexico and Colombia. Regional Worlds. Cultural Environments and Development Debates, Latin America: Annotated Bibliographies, Bibliographic Essays and Course Curriculum. Centre for Latin American Studies.

Posey, D. A., 2001. Biological and cultural diversity: The intrextricable, linked by land and politics. In L. Maffi (Ed.), On Biocultural Diversity: Linking Language, Knowledge, and the Environment (pp. 379-396). Washington DC: Smithsonian Institutional Press.

Swiderska, K., 2006. Protecting traditional knowledge: A framework based on customary laws and bio-cultural heritage. Paper for the International Conference on Endogenous Development and Bio-Cultural Diversity, COMPAS, Geneva.

Stevens, S., & De Lacy, T. (Eds.)., 1997. Conservation through cultural survival. Washington DC: Island Press.

UNPFII, 2007. Climate change, an overview. Paper prepared by the Secretariat of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.