Use and Management of “Muyong” in Ifugao Province, Northern Luzon Island in the Philippines

03.05.2010

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

03/05/2010

-

REGION :

-

South-Eastern Asia

-

COUNTRY :

-

Philippines (Ifugao Province)

-

SUMMARY :

-

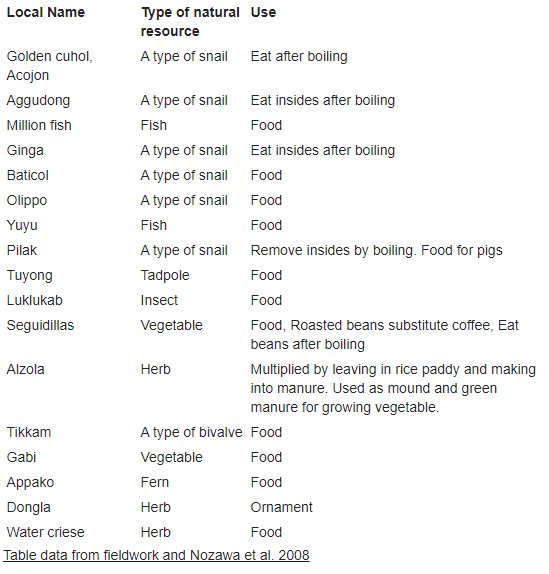

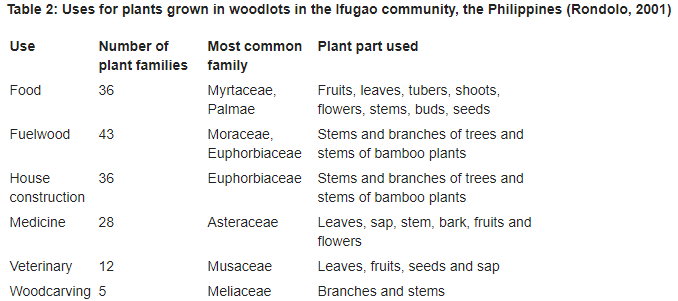

380 km north of Manila, the Ifugao landscape is shaped by common forest, privately owned forest (muyong), cultivated land, swidden, rice paddies and terraces, common grasslands, and settlement areas. Rice terraces spread from the bottom of the valley to the upper side of the mountain surface. Near the top of the hilly terrain, muyong and swidden are scattered in a mosaic-like pattern. Richly bio-diverse, this environment is dependent on the interactions of man and nature. There are two types of muyong: ・Uncultivated forest in areas not suitable for wet paddy farming, such as near the top of hilly terrain, have served as a source of useful plants for generations. ・Areas naturally regenerated or reforested after the cessation of slash-and-burn techniques, typically located in areas more easily cultivated. Private ownership is permitted of muyong, although they are usually open for use by kin and, in some cases, peripheral residents; maintenance work such as thinning, pruning and clearing underbrush is performed based on sustainable indigenous customs. Approval is required from the owner whenever logging is undertaken for building or woodcarving material, but it is not necessary for minor usage, such as firewood and fruit. The muyong, spread across the rice terrace slopes and the top of the hilly terrain, serve to reduce surface water runoff, restrict erosion and limit the harmful accumulation of dirt in the rice paddy fields below.

-

KEYWORD :

-

Muyong, paddy farming, swidden

-

AUTHOR:

-

Dr. Noboru Matsushima is a senior researcher at Japan Wildlife Research Center (JWRC). He is a socio-economist with a keen interest in favourable relationships between human activity and natural resource management in various developing countries. He has been implementing numerous field surveys in rural areas in Southeast Asia, China, the Middle and Near East, Africa, South America and the Pacific Islands, and making helpful suggestions since 1989. Mr. Yasuhiro Tojo is a researcher of Japan Wildlife Research Center (JWRC). His academic specialty is law and politics. Since joining JWRC in 2001, he has been involved in the work on the Japanese National Biodiversity Strategy and others.

-

LINK:

-

Protected Landscapes and Agrobiodiversity Values. Vol. 1. pp. 71-93

FAO Corporate Document Repository