The Ayllu System of the Potato Park, Cusco, Peru

03.05.2010

-

SUBMITTED ORGANISATION :

-

United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies

-

DATE OF SUBMISSION :

-

03/05/2010

-

REGION :

-

South America

-

COUNTRY :

-

Peru (Cusco)

-

SUMMARY :

-

Since pre-Hispanic times, a co-evolutionary relationship built around management of biocultural resources with the mountain environment in Cusco Valley, Peru, has produced the “ayllu” mindset. The main objective of “ayllu” is the attainment of well-being or Sumaq Qausay; defined as a positive relationship between humans and their social and natural environments. To this end, great focus is given to achieving equilibrium between one’s natural and social surroundings and to maintaining reciprocity between all “beings”; including the Earth. This practice has proven pivotal to maintaining high biodiversity and has been described by scholars as the product of “common-field agriculture” (Godoy, 1991). Attesting to this, the majority of subsistence and agricultural activities in the valley are based on diversifying uses and the priorities and values of the communities. This community focus can best be seen in the several economic collectives that have been established with the objective of conserving and sustainably using biological resources; examples include utilizing such tools as Local Biocultural Databases and audiovisual recordings that store traditional Andean biocultural knowledge, seed repatriation and conservation, and providing benefits for the often marginalised women of the Andes. This revitalization of traditional Andean systems is promoting a reciprocal relationship between the people of the Potato Park and their environment, enhancing the sustainable use of biodiversity, local livelihoods/human well-being and the ecological integrity of a landscape that is the product of a relationship millennia in the making.

-

KEYWORD :

-

bio-cultural resources, common-field agriculture, Peru

-

AUTHOR:

-

Mr. Alejandro Argumedo is Director of the Association ANDES, a Cusco-based indigenous people’s non-governmental organization working to protect and develop Andean biological and cultural diversity and the rights of indigenous peoples of Peru. He is also the international coordinator of the Indigenous People’s Biodiversity Network (IPBN), and Senior Research Officer for Peru of the ‘Sustaining Local Food Systems, Agricultural Biodiversity and Livelihoods’ Programme of the International Institute for Environment and Development for England. Mr. Bernard Yun Loong Wong works as a consultant for the Satoyama Initiative at the United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies. He specialises in forest ecosystem studies, where he combines ecology and history in demonstrating the contributions of past human activities to the establishment of old growth natural forests in Japan. His other interests include the philosophical and cultural aspects of traditional landscape formation, and historical interactions between people and the land.

-

LINK:

-

Homepage of the Potato Park

Homepage of the (NGO) Association ANDES

The Potato Park is a unique model of holistic conservation of the Andean traditional landscape with a focus on conservation of agrobiodiversity (Argumedo, 2008). The Park is located in a known microcenter of origin and diversity of potatoes, one of the world’s major food crops, which has been nurtured for centuries by the deeply rooted local food systems of Quechua peoples. The Potato Park initiative seeks to conserve the landscape and nurture the diversity of native crops, particularly of the potato, and their habitat, as well as enhance the interrelations between native crops and the physical, biotic, cultural environment, and to use such interactions to create multiple livelihood options for local people.

The Potato Park is a locally managed Indigenous Biocultural Territory using the Indigenous Biocultural Heritage Area (IBCHA) model developed by Asociación ANDES. The IBCHA model involves a community-led and rights-based approach to conservation based on indigenous traditions and philosophies of sustainability, and the use of local knowledge systems, skills and strategies related to the holistic and adaptive management of landscapes, ecosystems and biological and cultural assets. An IBCHA incorporates the best of contemporary science and conservation models and rights-based governance approaches, including the IUCN’s Category V Protected Areas (Philips, 2002), as well as positive and defensive protection mechanisms for safeguarding the Collective Biocultural Heritage (CBCH) of indigenous peoples 1.

The international conservation community is beginning to appreciate the need for new approaches to landscape conservation, based on local cultural and ecosystem contexts (Brown & Mitchell, 2000). This case study aims to illustrate an example of such a local approach and highlights how a traditional Andean system is promoting a reciprocal relationship between the people of the Potato Park and their environment, enhancing the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, local livelihoods/human well-being and the ecological integrity of a landscape that is the product of a relationship over millennia.

Photo 1: One of the communities in the Potato Park

1. Introducing the ayllu

The Potato Park is based on the ayllu approach. While most studies describe ayllu as a political and socio-economic system, few systematic analyses of the ayllu as an ecological phenomenon exist. We understand the ayllu as a community of individuals with the same interests and objectives linked through shared norms and principles with respect to humans, animals, rocks, spirits, mountains, lakes, rivers, pastures, food crops, wild life etc.

The following case study examines the ayllu from an ecological perspective with a particular focus on its importance for the management of landscapes and biodiversity. This interpretation and use of the ayllu concept offers the opportunity to appreciate the continued interactions between Andean peoples and the environment. Since pre-Hispanic times, the co-evolutionary relationship of the mountain environment through management of biocultural resources has produced the ayllu cultural landscape. While more recent political trends have displaced the ayllu as a political, economic and administrative system, as a cultural landscape it continues to be nurtured by Andean peoples.

The main objective of the ayllu is attainment of well-being. Well-being is defined as Sumaq Qausay, the ideal that is sought after by men and women, that translates into social, economic and political well-being through a full life. It expresses a relationship between human beings and their social and natural environments. It means to be in equilibrium with one’s natural and social surroundings and to maintain reciprocity between all beings, including Pacha Mama (Mother Earth).

The ayllu system during the Incan empire was defined based on parentage, and each ayllu was made up of an independent group with three levels of administration: the family level, the group of families that shared the same territory and a larger organizing unit that mobilized all groups. The territorial space of each ayllu was based on the resource needs of each group. Organization within each ayllu was determined by ecological zones within the territory, thus establishing division of labour and responsibilities among groups and families. Products from different ecological zones were exchanged based on family and group needs.

Verticality, the control of a number of economic niches at different altitudes, is a principle of Andean life. The sharp vertical changes of the Andes create microclimates within relatively short distances. Peoples and even individual communities or families in pre-Columbian times strove to control a number of ecological zones where different kinds of crops could be raised. A community might reside in the altiplano growing potatoes and quinoa, an Andean grain, but might also have fields in lower valleys to grow maize, and pastures miles away at a higher elevation for their llamas, and even an outer colony in the montana to provide cotton, coca, and other tropical products. In fact, access to a variety of these ecological zones determined pre-Columbian patterns of settlement and influenced the historical development of the Andean world.

Still today, the landscape is organized by ecological zones and the exchange of products allows for the fulfilment of livelihood needs across the zones. Agrarian cycles are used to organize collective labour in each zone so that productivity is maximized by using the available labour force to its full potential. Social organization is based on the exchange of labour and agricultural products between the zones. The principle of ayni (reciprocity) is thus fundamental in ensuring that each ecological zone is as productive as possible, contributing to Sumaq Qausay of the ayllu.

2. Overview of the Potato Park

The Potato Park is located within the Cusco Valley, covers at total of 9,280 hectares, and has a population of 3,880 inhabitants. The first human settlements in the area are dated at some 3,000 years ago. Human populations have been co-evolving with the Cusco Valley since then. Archaeological and historical records have named several successive cultures that have inhabited the valley, such as the Markavalli, Chananpata and Sawasiras, among others. In general, it is known that successive cultures had highly organized societies, based on principles of solidarity and respect. The Incas later founded their empire in Cusco, bringing their ancient traditions and religion to a large population, based on the principle of ayni, reciprocity. The sacred city of Cusco became the centre of Incan culture. For millennia, ancient Andean principles of reciprocity and interconnectedness have guided the interactions of people with the environment, producing the Andean landscape.

The European invasion and colonization of Peru had profound consequences for Andean landscapes, resource use and maintenance of sustainable food and economic systems for livelihoods. Today indigenous communities are confronting the impacts of colonialism by regaining their strength and inspiration from their own native identity and unique association with the land. Their survival is attributed to their endless patience and a profound spiritual reverence for the Pacha Mama and their ecological ayllu, and to their knowledge and innovation systems, which are based on sophisticated understanding of their mountain environment. This has provided them with an indigenous environmental ethic which has fuelled a conscious effort to preserve their environment and has propelled the creation of new mechanisms to conserve and sustain their natural resources. The case of the communities of the Potato Park demonstrates the deliberate efforts of Quechua communities to maintain diversity in domesticated and non-domesticated plants and animals, which characterizes Quechua farming systems, providing an important opportunity for a dynamic maintenance of genetic resources and landscapes.

Authority for the Park is shared between the villages, each of which elects one Chairperson to coordinate the work of the Association and concerted efforts are made to integrate traditional spiritual values, beliefs and understanding into the management.

2.1 Agrobiodiversity

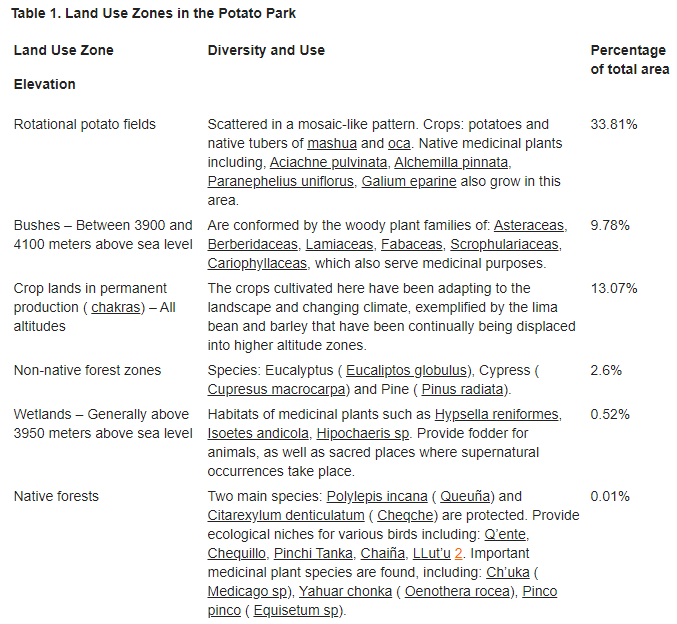

The main subsistence activity in the Potato Park is agriculture and animal husbandry (table 1). Approximately 13.07 per cent of the park area (approximately 1,133 hectares) is used for permanent agriculture of corn, tarwi, potatoes, beans, barley, and other crops. About 33.81 per cent of the park area is made up of tundra, or land that is resting. Crop rotation occurs every three to nine years. First, farmers cultivate potatoes, masha and oca, then the land is left fallow. During fallow periods, many medicinal plants can be found in these plots.

Pic 2: Potato and other crop fields in the Potato Park

The Potato Park is a centre of origin of the potato (CIP, 2008). The region is home to eight known native and cultivated species and 2,300 varieties, out of the 235 species and over 4,000 varieties found in the world. Also found in the region are 23 of over 200 wild species found in the world. The genetic diversity found within just one plot in the area can reach up to 150 varieties (Chawaytire community, Potato Park). Apart from potatoes, other native Andean crops such as olluco, beans, maize, quinua, wheat, tarwi, mashua and oca are produced. Beyond crop production for consumption, agriculture is also responsible for producing wool, medicine and wood. Other important functions of the agricultural system include food security, conservation, development and livelihoods and water conservation. Complementary economic activities include animal husbandry; sheep, cows and camelids.

The landscape of the Potato Park is the result of millennia of interactions between human populations and the environment and has been described by scholars as the product of ‘common-field agriculture’ (Godoy, 1991). ‘Common-field agriculture’ is a form of collective land management in which an assembly of farmers coordinates the production of crops and livestock grazing in managed fallow spaces among the designated sectors of a community: households have rights to parcels of land dispersed within common fields which are used by all for grazing and collection of resources such as wood The spatial and sequential organisation of land use in the Andes has been shown to be pivotal to maintaining a high biodiversity in the landscape (Godoy, 1991). This conceptualisation of Andean land management illustrates how productive activities organised collectively result in a landscape with high agrobiodiversity. Similarly, some have interpreted it as based on a landscape concept of space-based rotation and social organisation for access, providing a focus on the landscape as both environmental and productive, and social and cultural (Zimmerer, 2002). The biocultural system 3 approach of the ayllu system begins from an indigenous perspective, based on the Andean holistic worldview that recognises interconnectedness across all spheres of the cosmos, including the spiritual dimension. The landscape is much more than the product of agriculture; it is the product of holistic management.

2.2 Social organisation

There are six Quechua communities in the Potato Park. In 1993, the total population of the Potato Park was 3880 inhabitants, with a population density of 444 inhabitants per square kilometre. There is a small majority of women (50.2 per cent). 51.6 per cent of the population is between the ages of 15 to 64. 28 per cent is between the ages of 4 to 14, and 16 per cent of infants are younger than 4 years old. The communities rank in fourth place for extreme poverty and sixth regarding absolute poverty (RONAA, 2003).

The majority of the population is indigenous to the region, with only 1 per cent of the population being immigrants. There are two identifiable types of economic migration out of the Park: seasonal temporal migration and permanent migration. Seasonal migration is mainly undertaken by the heads of families who migrate to Quillambamba and the Cusco areas from January to April, during the period of least agricultural activity in the high altitude zones. These migrants work in coffee plantations and as labourers. There is however a small portion of mainly adult males from some communities that permanently work as porters for tourists hiking the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu.

2.3 Subsistence Activities

The Potato Park communities have developed subsistence mechanisms and social relations through adapting with their natural environment. The family unit is the productive unit and the vehicle for processing and planning future activities. Families in the more isolated communities continue to develop their productive activities with a focus on food security, using traditional technology and crops (such as potatoes), and conserving as much diversity as possible. Those living in more open communities supplement their agricultural activities with commercialisation of products and artisan work, or working outside of the Park, as porters for example.

The majority of subsistence activities are based on diversifying uses. For example, native potatoes are transformed into chuno or moraya for consumption, seeds, sale or barter. Agricultural products are used based on the priorities and values of the communities: (i) the best products are set aside for maintaining social relations, rituals and family consumption, (ii) products that are not as high quality are used for seed, barter and sale, (iii) the least desirable products are used for transformation or for animal feed, and (iv) the undesirable products are fed to the animals.

Women play an important role in the process, as they are the most knowledgeable in selection criteria and characteristics for the different uses. Women also manage the quantity of different types of product used. They are therefore ‘experts’ on both qualitative and quantitative value of their products, and can set a value on them for bartering purposes. Barter is mainly used at the household level, and women play a big part in managing the barter system.

2.4 Resilience of the natural environment

The Potato Park landscape came about through the interactions between local indigenous peoples, their mountain environment and the biocultural resources. The Potato Park landscape thus emerged from the natural resource management systems of Quechua people. In the historical review of the Potato Park landscape, it is possible to see how the indigenous biocultural system survived the colonial and modern attempts to displace Quechua people through land grabbing and the marginalization of Quechua social, cultural and economic life and customary laws, practices and institutions. Though the ayllu was dissolved as a social and political entity during this time, it remained an indigenous cultural landscape. The ayllu landscape not only survived but it adopted the best of the newcomers’ resources and practices. This approach strengthened its main features, enabling it to reproduce itself, forming a rich mosaic of productive and natural areas that provide habitats for all the beings with whom they share their territory.

Resilience is understood through the Andean awareness of complex and chaotic interactions producing order. Supporting adaptation becomes an important aspect of management. The high diversity found in the landscape supports adaptive capacity to build resilience. Andean ecosystems are complex, with multiple interacting parts creating a diverse topography. Non-linear interactions create chaotic behaviour through extreme changes in conditions such as extreme weather, providing a sense of disorder within the Andean natural environment. However, order emerges out of the complex interactions and traditional practices. Order in the Andes is interpreted through the Andean principle of equilibrium, which is understood as emerging out of constant change. It is the product of a flow of vital and cosmic energy moving dynamically. The holistic worldview recognises that all elements continue on a cycle that is continuously renewed, and they are intermingled; the economic, social, physical all are part of the same dynamic interactions. This is most obviously appreciated through ritual practice in which offerings to deities allow the reestablishment of the cosmic energy – they ensure that the principle of reciprocity is maintained.

Andean principles of equilibrium and reciprocity facilitate natural and social order – illustrating a profound awareness of chaotic and complex systems and non-linear dynamics. Resilience of complex systems is maintained through supporting their adaptive capacity which gives them the ability to deal with perturbations without losing their key functions. According to the Andean worldview, disasters, or loss of resilience, are the result of a loss of reciprocity. Reciprocity guides interactions and build resilience in the natural and social environments. The relationships are based on intimacy, respect, understanding and communication, establishing adaptive and creative mechanisms for dealing with changes and novel situations without reducing future options.

3. Integration of local traditional ecological knowledge in the Potato Park

One of the goals of the Potato Park has been to establish an alternative development model, which is inclusive, and supports cultural identity and conservation of biocultural heritage.

3.1 Economic Collectives

ANDES and the Potato Park worked together in establishing several economic collectives with the objective of conserving and sustainably using biological resources and achieving a creative and solid economy based on those resources. The collectives include the Potato Arariwas (a seed repatriation and conservation collective), the gatronomy Qachun Waqachi collective, the Tika Tijillay women’s video collective, the Naupa Awana craft collective, the Willaqkuna guides collective, and the Sipaswarmi Medicinal Plants Collective.

Photo 3: Restaurant co-managed by the six communities in the Potato Park

Indigenous women in the rural areas of Peru are often marginalized in health, education and legal services, as well as in opportunities for employment. The rich biological resources and associated traditional knowledge are in danger of disappearing due to the lack of recognition of the rights of indigenous women. Today, the production of herbal medicines provides safe low cost medicines for families in the Potato Park, and the production and processing of herbal products for sale to tourists also provides additional income generating opportunities for local women. Their traditional knowledge is promoted and protected through the use of a multimedia database. All of the products made by the women are based on their traditional knowledge using local medicinal plants, while elements of western medicine are also introduced, such as first aid, preventative medicine and treatment options which harmonize with traditional medicine.

3.2 Biocultural Databases

The Park has developed Local Biocultural Databases based on the traditional Andean system of Khipus. Khipus were used during prehispanic times to collect and store information, including information related to biological resources. The result of applying the Khipus system to biocultural databases is an adaptive system that allows capture, registration, storage and administration of indigenous knowledge based on Andean traditional science and technology. It is a tool that can be used to conserve, promote and protect local knowledge, thus becoming useful in facing political, social and technological challenges that are all too common in this era of globalisation. The methods and tools used are suited to oral and visual knowledge models. They include audiovisual information, matrices of biodiversity, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and free software. Local protocols based on customary laws are used to regulate access to the information.

Photo 4: Women participating in the Workshop at the Potato Park

3.3 Schemes for passing on various traditional wisdom to the next generation

An important strategy used in the Potato Park for analysis, discussion and debate for generation of new knowledge and wisdom is the use of Thematic Study Groups, to propose alternative solutions to local conservation and development problems for general well-being. More specifically, their objective is to systematically gather and analyse existing local knowledge and to generate new knowledge through dialogue. Local traditional knowledge platforms are also used as organisational structures and mechanisms to facilitate horizontal transmission of knowledge, experiences and wisdom from farmer to farmer, and community to community. They also support local governance systems based on Andean principles of reciprocity, duality, solidarity and respect. They are facilitated by local technicians and their participation with collective groups such as the study groups and the business groups that participate in other aspects of conservation and development.

3.4 Participatory Mapping

Visualizing indigenous people’s spatial knowledge through cognitive maps has been an important part of the Potato Park action research efforts. Participatory mapping in the Potato Park has focused on capturing the spatial knowledge of local people such as location, size, distance, direction, shape, pattern, movement and inter-object relations as they know and conceive it to develop Cognitive Maps, which are internal representation of their world and its spatial properties stored in their historic memory.

4. Planning for the purpose of optimizing ecosystem services

4.1 Multi-layered land use/ mosaic type of land use

The entire landscape of the Potato Park is a mosaic of land use zones, formed by practices of land use such as those highlighted in the previous section. Field terraces spread from the bottom of the valley all the way to the steep mountainsides. Common native forest species are interspersed with exotic eucalyptus forest. Other areas include communal grasslands containing the following species. Bushes near bodies of water regulate the water table, limiting the evapotranspiration by covering the soil. Near the top of the mountain terrain, rotational native potato fields are scattered in a mosaic-like pattern. The fields are in rotation for periods of three to nine years and during their first years of cultivation potatoes are yielded, while in proceeding years the other native tubers of mashua and oca are cultivated prior to allowing the soil to rest. Crop lands in permanent production ( chakras) represent are found throughout the vertical zones. The crops cultivated here have been adapting to the landscape and changing climate, exemplified by the lima bean and barley that have continually been displaced into higher altitude zones. The constant adjustment and relocation due to the adaptability of food crops has therefore necessitated that the human populations live in higher altitude zones.

4.2 Dynamic management of land and resources

In an effort to strengthen the resilience of their socio-ecological system in 2004 the Association of Communities of the Potato Park signed a landmark Agreement with the International Potato Centre (CIP) on the Repatriation, Restoration and Monitoring of Agro-biodiversity of Native Potatoes and Associated Community Knowledge Systems. The objective of this agreement was to restore the genetic diversity of the native potato in the area and promote its conservation and sustainably use. Thus far, the agreement has led to the repatriation of 492 varieties of potatoes held by CIP. These varieties have been reintroduced in the area, and have positively affected local food security, economic development, cultural revival and farmer’s rights. This project resulted also in the development of a Dynamic Conservation approach that links in-situ and ex-situ conservation strategies in one dynamic, mutually supportive strategy. This has strengthened the model of the Park as a holistic and effective approach for the conservation and sustainable use of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture.

Photo 5: Seed repatriation and conservation center in the Potato Park

4.3 Application of the concept of adaptive management

Adaptive management is an approach to environmental management that recognises dealing with uncertainty and change as necessary when dealing with complex systems (Holling, 1978; Lee, 1993). The approach advocates for systematic experiments to be undertaken, developing alternative hypotheses, supporting adaptive learning to deal with constant change. A yllu management can be called an active adaptive management system due to an explicit focus on learning as a vehicle for improving practice. Moreover, it is inherently adaptive, because of the focus on processes and relationships. The holistic framework that keeps it all together requires that processes become the focus of management. Ayni as a guiding principle serves this purpose, as well as uniting the spiritual with the practical.

4.4 Cyclic use of natural resources

An example of how resources are reused and recycled in the Park is the practice of organic fertilization and seed collection. Organic fertilizer is obtained from family livestock or from livestock belonging to other families of the community, or from the forest. This method of obtaining fertilizer is only incorporated in potato cultivation, while the cultivation of oca and papalisa, as well as the grains, planted in the same space in the next agricultural cycle and the one following that, benefit from the residual effect of this initial fertilization.

5.Conclusions

The Potato Park, as an example of revitalising the ayllu cultural landscape, has generated social, cultural, environmental, economic and political benefits to the communities. Communities have strengthened their intercommunity networks, generating synergies through creating intercommunity groups. These include the economic collectives, and the Association of the Communities of the Potato Park, bringing together all of the communities for decision-making. Women, as a major interest group have a leading role in implementing action in the Park, and their participation in decision-making is being strengthened currently. Similarly through participation in economic collectives they also contribute to family economies. Culture is strengthened through implementation of the Potato Park because it reinforces the role of local culture through institutions, promoting regeneration of community identities. Other positive impacts include the restitution of genetic variability of native potato crops, repatriation and restoration of the cultural landscape; agro-ecotourism generating income and incentives for conservation and the promotion of regional ordinances.

This study was conducted as part of the program activities of the Satoyama Initiative, United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies.

References

Argumedo, A (2008) The Potato Park, Peru: Conserving agrobiodiversity in an Andean Indigenous Biocultural Heritage Area, in Amend, T., Brown, J., Kothari A., Phillips, A., Stolton, S. eds. Protected Landscapes and Agrobiodiversity Values. Vol 1 in the series, Protected Landscapes and Seascapes, IUCN & GTZ. Kaspareg Verlag, Heidelberg.

Brown, J., Mitchell, N. 2000. Culture and nature in the protection of Andean landscapes Mountain Research and Development,20(3) 212-217.

CIP 2008. http://www.cipotato.org/pressroom/press_releases_detail.asp?cod=23 Guillet, D. 1983. Toward a cultural ecology of mountains: The central Andes and the Himalayas compared Current Anthropology 24(5) 561-574

Godoy, R. 1991. The evolution of common-field agriculture in the Andes: A hypothesis, Society for Comparative Study of Society and History, Vol 33, No. 2 pp. 354-414Nickel, C. 1982. The semiotics of Andean terracing Art Journal, Fall edition

Holling, C. S. (Ed.). (1978). Adaptive environmental assessment and management. New York: John Wiley.

Phillips, A, (2002). Management Guidelines for IUCN Category V Protected Areas Protected Landscapes/Seascapes. World Commission on Protected Areas. Best Practice Protected Area Guideline Series No. 9, IUCN.

Zimmerer, K. S. (2002) Common field agriculture as a cultural landscape of Latin America: development and history in the geographical customs of resource use. Journal of Cultural Geography,19.2, 37(27)

Notes

- 1. CBCH includes the cultural heritage, i.e. both the tangible and intangible including customary law, folklore, spiritual values, knowledge, innovations and practices and local livelihood and economic strategies, and the biological heritage, i.e. diversity of genes, varieties, species and ecosystem provisioning and regulating, of indigenous communities which are often inextricably linked through the interaction between local peoples and nature over time and shaped by their socio-ecological context (ANDES, 2007)

- 2. Orestes Castañeda Potato Park technician

- 3.A complex socio-ecological system with interconnected parts that is characterised by high biocultural diversity and is the product of a coevolutionary interaction between people and the environment in a particular locality.